Professional Documents

Culture Documents

841 A Review of Extraordinary Bodies Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature by Rosemarie Garland Thomson

Uploaded by

Anshula UpadhyayOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

841 A Review of Extraordinary Bodies Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature by Rosemarie Garland Thomson

Uploaded by

Anshula UpadhyayCopyright:

Available Formats

A review of

“Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American

Culture and Literature Rosemarie by Garland Thomson”

By Justin Holliday

Rosemarie Garland Thomson’s book Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring

Disability in American Culture and Literature has made a significant contribution

by looking at disability from a humanities perspective. Thomson introduces the

concept of the “normate,” a figure “who, by way of the bodily configurations

and cultural capital they assume, can step into a position of authority” (p. 8);

this term has become so important that other theorists such as Robert McRuer

have incorporated it in their work. The “normate” contrasts with the disabled

body, but for Thomson, this difference is the result of sociocultural influence

rather than a natural difference. In her analysis of the freak show and nineteenth-

and twentieth-century literature, Thomson incisively exposes the tenuous

social construction of the disabled body in American culture and notes how

these representations have shifted attitudes toward people with disabilities

from monstrous spectacles to medical specimens. Ultimately, she argues for a

politics of accommodation instead of the historic compensatory model because

accommodation indicates a need to change the environment rather than to

shame or pity the person.

Thomson grounds her arguments about the cultural power of freak shows

and literature in feminist and poststructuralist theory to illustrate how the

disabled body is viewed as inadequate. Notably, Thomson intersects disability

with feminism, especially “standpoint theory, which recognizes the immediacy

and complexity of physical existence” (p. 24). Rather than homogenize any

group, Thomson notes that we should consider individual differences; she also

acknowledges the wide range of disabilities, which can make this particular

marginalized group feel more separated but shows that the intersectionality of

social markers can bring people from different backgrounds together. Thomson

also addresses the cultural attitudes toward disability are based on various

factors, including its association with femininity, something that the dominant

group attempts to control, which becomes significant in her later discussions of

the extraordinary female body as out of control. Then, she connects her feminist

framework to analyses of Erving Goffman, Mary Douglas, and Michel Foucault

to show how societies exert control over bodies, asserting that anomalies are

repudiated (Douglas), or stigmatized (Goffman).

To illustrate this curtailing of the disabled body, Thomson then shifts

her focus to the freak show, which allows her to trace American perceptions of

people with disabilities. From the monster in Ancient Greece to the “freak” of the

nineteenth- and early twentieth-century freak shows, people with disabilities

have been stigmatized as ‘Other’, as figures of admonition. As she later does in

her analysis of literature, Thomson successfully illustrates the intersectional

power of racism, sexism, and ableism in figures such as “The Hottentot Venus,”

Sartje Baartman, and “The Ugliest Woman in the World,” Julia Pastrana (p. 70).

These women, along with so many others, were paraded before crowds not only

for entertainment; according to Thomson, freaks were sources of anxiety, and

in particular, Baartman exemplified feminine sexuality out of control and thus

was used as a justification for the affirmation of restrictive nineteenth-century

American womanhood and the curtailment of women’s sexuality.

But, as Thomson notes, the freak gave way to the sympathetic figure

once medicalization abrogated the supposed “monstrousness” of disability

though not its abjection; Thomson critiques the sentimental fiction of Harriet

Beecher Stowe, Rebecca Harding Davis, and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, who all

problematically invoke the sympathetic, disabled figure to link white, middle-

class women’s pursuit for social reform. Only Stowe ostensibly racializes

her disabled characters, but by doing so, she contrasts them with “maternal

benevolence” (p. 88) of white characters, showing how even a childlike

Eva has a higher social rank, which enables her to take care of the African

American characters. Although Davis and Phelps do not use race as a social

marker to differentiate between characters and their ability, they focus on

class distinctions, and in the case of Phelps, a rising consumerist response to

feminine beauty. Thus, even as the novels attempt evoke sympathy for the

disabled female characters, the idealized woman is white, middle-class, and

conventionally beautiful, rendering women who fall out these categories not only

unfortunate, but also outside femininity, even outside womanhood.

Thomson’s final chapter, however, demonstrates the shift of cultural

attitudes toward people with disabilities in twentieth-century African American

women’s literature, which revises disability as a marker of identity to celebrate.

Once again, race, gender, and ability come into play with one another as

Thomson analyzes the works of Ann Petry, Toni Morrison, and Audre Lorde.

These books acknowledge oppression, but the characters do not succumb (with

rare exceptions, such as Pauline Breedlove in The Bluest Eye); instead, they

proudly affirm their identities. Thomson seamlessly intersects the changing

attitudes toward disability from Petry’s depiction of disability as grotesque to

an insightfully woven examination of Morrison’s first five novels, in which bodies

that we may considered disabled are actually “physical witnesses to violation

and oppression” (p. 116). Acting as “witnesses” to history, these black female

bodies can reclaim power in a patriarchal, ableist society.

Further, Thomson notes the power of reclamation in her discussion

of Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, which appropriates blackness,

womanhood, and disability as sources of power. These books show that

rejecting assimilation is the only way to fight subjugation and live. By rendering

disability as a celebratory ontology, Thomson successfully exemplifies the need

for a politics of accommodation wherein people with disabilities do not need

to change their bodies, but rather, the environment should be modified to

accommodate their needs.

The only criticism I have against Thomson is her claim, “Morrison’s novels

revise Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (131). While she provides links between characters

in Stowe and Morrison’s fiction (e.g. Topsy/Sula), she risks being reductive by

arguing that Morrison is working directly from Stowe rather than inventing

characters that do not rely on Stowe’s stereotypes, even if only to revise and

reinvigorate them with power. Although Stowe has had only influence on literary

depictions of slavery, this interpretation may overshadow the African influence

on Morrison’s work.

You might also like

- Eckhart Tolle and Sri AurobindoDocument186 pagesEckhart Tolle and Sri AurobindoAntonella ErcolaniNo ratings yet

- Feminism Without WomenDocument6 pagesFeminism Without WomenAlton Melvar M Dapanas100% (1)

- "Feenin" POSTHUMAN VOICES IN CONTEMPORARY BLACK POPULAR MUSIC - Alexander WeheliyeDocument28 pages"Feenin" POSTHUMAN VOICES IN CONTEMPORARY BLACK POPULAR MUSIC - Alexander WeheliyeJef Tate100% (1)

- Twelve Steps To Pair BondingDocument4 pagesTwelve Steps To Pair BondingHorace Prophetic DavisNo ratings yet

- The American ScholarDocument5 pagesThe American ScholarGiulia Iluta100% (1)

- A Brief Text-Book of Logic and Mental PhilosophyDocument294 pagesA Brief Text-Book of Logic and Mental PhilosophyYonnerz MullerNo ratings yet

- David Hartman Maim On Ides Torah and Philosophic QuestDocument315 pagesDavid Hartman Maim On Ides Torah and Philosophic QuestDaniel Sultan100% (2)

- An Analysis On To The Man I MarriedDocument10 pagesAn Analysis On To The Man I MarriedanneNo ratings yet

- What I BelieveDocument8 pagesWhat I BelievePhyllis GrahamNo ratings yet

- Fragmented Female Body and IdentityDocument23 pagesFragmented Female Body and IdentityTatjana BarthesNo ratings yet

- Bequeathing of The Key of ResponsibilityDocument2 pagesBequeathing of The Key of ResponsibilityAvegail Alarcon100% (3)

- Writing and Deconstruction of Classical TalesDocument4 pagesWriting and Deconstruction of Classical TalesEcho MartinezNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument217 pagesUntitledDiogo M.No ratings yet

- Jacques Lacan The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book IV The Object RelationDocument520 pagesJacques Lacan The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book IV The Object RelationAzinTavakoli100% (1)

- Feminist Approach in Literary TextsDocument8 pagesFeminist Approach in Literary TextsAlaine DobleNo ratings yet

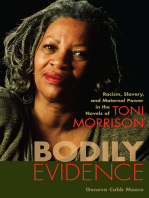

- Bodily Evidence: Racism, Slavery, and Maternal Power in the Novels of Toni MorrisonFrom EverandBodily Evidence: Racism, Slavery, and Maternal Power in the Novels of Toni MorrisonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Decolonizing Feminisms: Race, Gender, and Empire-buildingFrom EverandDecolonizing Feminisms: Race, Gender, and Empire-buildingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Christian Doctrine of SalvationDocument15 pagesThe Christian Doctrine of SalvationAlingal CmrmNo ratings yet

- D'Urbervilles As A Means of Men's Struggle To Establish Their Superiority Over Women, HenceDocument11 pagesD'Urbervilles As A Means of Men's Struggle To Establish Their Superiority Over Women, HenceAbdul Saeed ShahNo ratings yet

- Gender, Sex, and Disability From Helen Keller To Tiny Tim: Sarah E. ChinnDocument9 pagesGender, Sex, and Disability From Helen Keller To Tiny Tim: Sarah E. ChinnJody AbotNo ratings yet

- Frey-Sc-Scarlet Letter Final Draft and Reflective EssayDocument28 pagesFrey-Sc-Scarlet Letter Final Draft and Reflective Essayapi-242692028No ratings yet

- The Bluest Eye ReferenceDocument14 pagesThe Bluest Eye ReferenceSensai KamakshiNo ratings yet

- Of Woman Born Motherhood As Experience ADocument4 pagesOf Woman Born Motherhood As Experience AAntonio MNo ratings yet

- Reclaiming Postcolonial Identity in Pramoedya Ananta Toer's "This Earth of Mankind" and Arundathi Roy's "The God of Small Things"Document10 pagesReclaiming Postcolonial Identity in Pramoedya Ananta Toer's "This Earth of Mankind" and Arundathi Roy's "The God of Small Things"Julia Alessandra TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Review Essay: Trish SalahDocument6 pagesReview Essay: Trish SalahHR SequoiaNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument30 pagesChapterKamran Ali AbbasiNo ratings yet

- A Vindication of The Rights of A Woman Was One of The Precursor Books OnDocument4 pagesA Vindication of The Rights of A Woman Was One of The Precursor Books OnBruno DFNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3: Writing and Deconstruction of Classical TalesDocument6 pagesLesson 3: Writing and Deconstruction of Classical Talesfretzielasala000No ratings yet

- Stanford 1993Document15 pagesStanford 1993DinaNo ratings yet

- 43-46 PDFDocument4 pages43-46 PDFEyarkai NambiNo ratings yet

- Shadows To Walk: Ursula Le Guin's Transgressions in Utopia: William MarcellinoDocument11 pagesShadows To Walk: Ursula Le Guin's Transgressions in Utopia: William MarcellinoSiminaNo ratings yet

- JANFEB - Wilderson KDocument12 pagesJANFEB - Wilderson KCedric ZhouNo ratings yet

- Towards Definitions of Feminist Writing SummaryDocument5 pagesTowards Definitions of Feminist Writing Summarylunaluss100% (1)

- Chapter OneDocument13 pagesChapter OnePragya KumarNo ratings yet

- Narratology pdf111Document5 pagesNarratology pdf111smart_eng2009No ratings yet

- Humor and Ambivalence in The Novels of TDocument17 pagesHumor and Ambivalence in The Novels of TjuliaNo ratings yet

- Hall, Kim - Feminism, Disability, and EmbodimentDocument8 pagesHall, Kim - Feminism, Disability, and EmbodimentCaitlinNo ratings yet

- Feminism - Lois TysonDocument3 pagesFeminism - Lois TysonVika TroianNo ratings yet

- Construction of The Queer Feminine IdentityDocument18 pagesConstruction of The Queer Feminine IdentityGabs SemanskyNo ratings yet

- Paper # 2Document11 pagesPaper # 2Claire ValsecchiNo ratings yet

- Femme Challenge in FictionDocument15 pagesFemme Challenge in FictionKennia Briseño RivasNo ratings yet

- Feminist Critics and Their TheoriesDocument7 pagesFeminist Critics and Their TheoriesMANJUNATH BHEEMANNAVARNo ratings yet

- The Cultivation and Prevalence of White Supremacy in American Law & SocietyDocument20 pagesThe Cultivation and Prevalence of White Supremacy in American Law & SocietyHershey SuriNo ratings yet

- English OralDocument3 pagesEnglish OralMilla RamnebroNo ratings yet

- Feminist CriticDocument62 pagesFeminist CriticEbrar BaşyiğitNo ratings yet

- Feminist CriticDocument43 pagesFeminist CriticEbrar BaşyiğitNo ratings yet

- Writing and Deconstruction of Classical TalesDocument7 pagesWriting and Deconstruction of Classical TalesArjie Maningcay ArcoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 86.0.247.19 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 04:40:07 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 86.0.247.19 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 04:40:07 UTCbookasessionwitharashNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and FeminismDocument22 pagesPostmodernism and FeminismarosecellarNo ratings yet

- FEMINISMDocument2 pagesFEMINISMAngelica Maye P. AgraanNo ratings yet

- Feminist Interpretation of Kafka and IbsenDocument22 pagesFeminist Interpretation of Kafka and IbsenZerin JahanNo ratings yet

- MarxismDocument2 pagesMarxismMonaliza GamposilaoNo ratings yet

- Brave New World: Name: Taufik Mustangin NIM: 2109120156 Class: 3 HDocument5 pagesBrave New World: Name: Taufik Mustangin NIM: 2109120156 Class: 3 HIrwan Taufik MustanginNo ratings yet

- Gender and Self-Disgrace and Cora UnashamedDocument3 pagesGender and Self-Disgrace and Cora Unashamedaayushi bakshiNo ratings yet

- Critical Essay On "The Passion"Document11 pagesCritical Essay On "The Passion"Celeste Moore100% (2)

- Hall's Theory of Representation On Morrison's BelovedDocument6 pagesHall's Theory of Representation On Morrison's BelovedSandhya AdhikariNo ratings yet

- (Anti) Gay Utopian Fiction in English and Romance Languages: An OverviewDocument31 pages(Anti) Gay Utopian Fiction in English and Romance Languages: An OverviewPedro FortunatoNo ratings yet

- 3.redeeming FullDocument8 pages3.redeeming FullTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Whole PDFDocument276 pagesWhole PDFremmyamanecerNo ratings yet

- Gender, Ontology, and The Power of The Patriarchy: A Postmodern Feminist Analysis of Octavia Butler's Wild Seed and Margaret Atwood'sDocument21 pagesGender, Ontology, and The Power of The Patriarchy: A Postmodern Feminist Analysis of Octavia Butler's Wild Seed and Margaret Atwood'sx92q9rwjmgNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Muhammad Tahir SAP ID 26802Document9 pagesResearch Proposal Muhammad Tahir SAP ID 26802Muhammad TahirNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Callaloo: This Content Downloaded From 99.115.155.193 On Sun, 12 Mar 2023 18:57:53 UTCDocument17 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press Callaloo: This Content Downloaded From 99.115.155.193 On Sun, 12 Mar 2023 18:57:53 UTCBrianna JonesNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Other Wes MooreDocument3 pagesEssay On The Other Wes Mooremywofod1nud2100% (2)

- Feminist Literary TheoryDocument8 pagesFeminist Literary TheoryswarnaNo ratings yet

- AIC3003 Alternative AssessmentDocument3 pagesAIC3003 Alternative AssessmentTianjiao JingNo ratings yet

- Objectification in Music Videos - CurrentDocument8 pagesObjectification in Music Videos - Currentapi-269801335100% (1)

- Language of Literary PaperDocument19 pagesLanguage of Literary PaperKeven Ong OpaminNo ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument45 pagesReview of LiteratureSanath KumarNo ratings yet

- Inbound 5956715336762113698Document5 pagesInbound 5956715336762113698Curthny MorenoNo ratings yet

- LSC Uos Ba in Business Studies: Assignment BriefDocument12 pagesLSC Uos Ba in Business Studies: Assignment BriefSheryl CaneteNo ratings yet

- Gertrude by Hermann HesseDocument207 pagesGertrude by Hermann HesseIury CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of PythagorasDocument4 pagesPhilosophy of PythagorasAnotherGalaxyNo ratings yet

- Are Theorys of LearningDocument24 pagesAre Theorys of LearningMarina EstevesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Logic Syllogisms-1: Class ExerciseDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Logic Syllogisms-1: Class ExercisePriyanshu PrakashNo ratings yet

- The Spiritual Diary Ignatius Loyola OF: Byjoseph MunitizDocument16 pagesThe Spiritual Diary Ignatius Loyola OF: Byjoseph MunitizNathan RoytersNo ratings yet

- At The End of The Lesson, The Learners Will Be Able ToDocument3 pagesAt The End of The Lesson, The Learners Will Be Able ToAries Venlym TanolaNo ratings yet

- Pymetrics Approach: David Ukaegbu Jan. 4, 2024Document5 pagesPymetrics Approach: David Ukaegbu Jan. 4, 2024David UkaegbuNo ratings yet

- Reading and Teaching Henry GirouxDocument17 pagesReading and Teaching Henry GirouxKimNo ratings yet

- Human Dignity Humility.Document13 pagesHuman Dignity Humility.Komarneni PramoddNo ratings yet

- Xi. Adjustment and Enhancement of The SelfDocument2 pagesXi. Adjustment and Enhancement of The SelfRaymond AnactaNo ratings yet

- Marx Social Change TheoryDocument4 pagesMarx Social Change Theoryanon_482261011No ratings yet

- Bureaucracy: Is It Efficient? Is It Not? Is That The Question? Uncertainty Reduction: An Ignored Element of Bureaucratic RationalityDocument24 pagesBureaucracy: Is It Efficient? Is It Not? Is That The Question? Uncertainty Reduction: An Ignored Element of Bureaucratic RationalityJay-son LuisNo ratings yet

- On Children - English NotesDocument7 pagesOn Children - English NotesikeaNo ratings yet

- Islam Through Western EyesDocument4 pagesIslam Through Western EyesAli AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Story of An Hour (Kate Chopin)Document8 pagesThe Story of An Hour (Kate Chopin)Sarah CrutaNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Life-Changing Affirma - Robert B StoneDocument56 pagesThe Complete Book of Life-Changing Affirma - Robert B StoneBastian MichelsNo ratings yet

- Eli K-1 Lesson 1Document6 pagesEli K-1 Lesson 1ENo ratings yet

- Dhanisha Lolam - Bs Workshop AssignmentDocument5 pagesDhanisha Lolam - Bs Workshop AssignmentSonu LolamNo ratings yet

- Prahlad MaharajDocument7 pagesPrahlad MaharajGaura PremiNo ratings yet

- Vampire Character QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesVampire Character QuestionnaireLucas Mendes de SouzaNo ratings yet