Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 - CHRISTIAN POETRY AND PROSE Epathshala PDF

Uploaded by

pinkyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 - CHRISTIAN POETRY AND PROSE Epathshala PDF

Uploaded by

pinkyCopyright:

Available Formats

MODULE III

CHRISTIAN POETRY AND PROSE

In this module you are going to learn:

The effects of Christianity on Anglo-Saxon literature

Anglo-Latin phase: Aldhelm, Bede and Alcuin

Works of Caedmon and Cynewulf and other religious poems

Anglo-Saxon prose: Alfred, Aelfric, Wulfstan

Effects of Christianity on Anglo-Saxon Literature

You have already read about the advent of Christianity in the island and how it spread among the

people in the first module. Now we shall discuss why learning becomes an important component in

the Christianisation process of the island and how it influenced literature.

Christianity is pre-eminently a literary religion, which means it is based on the reading and

understanding of the sacred text. The text is a complex one; it required philosophical understanding

and scholarly interpretations. Such documents could not be just remembered and sung, they must be

written down, documented, and interpreted and made simpler for the common people to understand

the religious ideas. The church thus became the seat of learning as there was no separate institution

for spreading mass education. The clerics were usually well-versed in Latin as that was considered to

be the language of the learned though translation of important classical books were deemed to be

important to spread the word of god to a greater number of people. We also have a body of poetical

renderings of the biblical literature in vernacular, which are attributed to the layman poets like

Caedmon and an unknown poet like Cynewulf. Apart from these we also have some homiletic poems

in some manuscripts which also prove the fact that Christianity had influenced not only the clerics

who definitely had some agenda in mind, but the common people of the country whose world view

changed due to this religious conversion. The knowledge of Bible did not only offer a new faith but a

different understanding of the human condition. Previously, kings would trace their origin to Sceaf

but now they would relate themselves to Adam and Eve and place themselves in this divine scheme of

things. Thus the understanding of past was considerably altered. The heroes like Beowulf were

replaced by Christ the hero.

The knowledge of Bible was chiefly symbolic. The text is not just supposed to be read as a set of

stories of different men and women, and the events are not mere results of their moral virtues and

vices, rather, the text has to be understood holistically as the justification of the ‘ways of God to men’.

It has a philosophical significance which one would miss if one reads the text too literally. Hence, the

need was felt to write the resultant literature in the forms of allegory which attains a sort of perfection

in the Middle Ages. Allegory, as a literary style could operate at many levels, it could contain an

individual believer’s faith and also the deeper theological counsel.

Unit I, Module III, p 1

However, you must bear in mind the fact that these Old English poets had Anglo-Saxon forefathers

and thus they imagined the Christian God in the image of their kings, and his angels as thanes. Their

religious universe was just an extension of their heroic world. Thus, the imagery presents a curious

mixture of Christian values in Anglo-Saxon moulds.

For example, in Exodus, Moses is presented as a

Germanic war-leader, the Israelites, a loyal and INSULAR HAND

courageous army exhibiting all the heroic virtues. Such

effects of Germanization of course become less and

less pronounced as the society gradually shifted to the

feudal economic system.

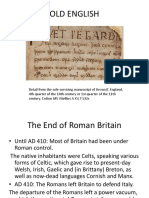

The Anglo-Saxons used the runic alphabet which had

twenty-four letters to write. These letters were

epigraphic in nature and therefore could only be cut or

hammered out on hard surfaces. This sort of writing

was not very useful for writing long literary

compositions; besides such writing was quite

expensive and the poets were more interested in

performing than writing them down. But with the

advent of Christianity a huge change took place. The

missionaries brought parchment, pen and ink, along

with the Roman alphabet which were primarily used to

record English texts as well. Later however, they

developed their own insular hand. In Old English times The script that was used to write the

Latin and Old English texts is known

church monopolised the production of manuscripts for

as the insular hand. The script is

the layman would not know how to write. The characterized by thick initial strokes

educated men would know both Latin and Old English, and heavy shading developed from

and at first they would compose mostly in Latin. Later, half-uncial (having the features of

however, the literature was written mostly in the both the uncial and the cursive style

of writing) under the influence of the

vernacular. uncial used by the Irish scribes about

th th

the 5 and 6 centuries and used in

Anglo-Latin literature: Aldhelm, Bede and Alcuin England until the Norman conquest

and in Ireland with modifications to

Aldhem (c. 640-709) the present day.

th

He was the bishop of Sherborne. He wrote both in Around 8 century Alcuin used this

English and Latin, but since the English compositions style to allow the division of writing

were not deemed to be important they were not into sentences and paragraphs by

beginning sentences with capital

preserved. Thus his extant works, both in prose and letters and ending them with periods.

verse, are in Latin; it comprises of a collection letters, a

series of riddles, and a learned treatise in praise of (Source: Miriam Webster and

Encyclopaedia Britannica Web)

Virginity. His style was artificial, full of archaic words

and circumlocution.

Bede (673-735)

Bede, also known as ‘The Venerable’ for his learning, spent his life in the Northumbrian monasteries

of Wearmouth and Jarrow. He produced as many as forty books on theological, historical and

scientific subjects. Though most of his works are in Latin, he is supposed to have translated the

Unit I, Module III, p 2

Gospel of St John, which is lost and his five-line long death song in Old English. Bede wrote

homilies, commentaries on the Latin Church fathers, Latin hymns, and two biographies of St

Cuthbert, an English bishop who died in 687.

His most famous works are: De Natura Rerum (Concerning the Nature of Things), and Historia

Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation). Ecclesiastical History

was completed in 731 and was translated by King Alfred at the end of the following century. This

document has extreme historical significance for it is an important and almost the only source to

knowing Anglo-Saxon history (the other important books are Germania by Tacitus which records the

history of the Germanic People and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle which was written in 8th century

under the patronage of King Alfred). Divided in five books, the Ecclesiastical History records the

early history of England, the struggle between the Celtic and Roman churches, and the gradual

conversion of the people. Some narratives are oft-quoted, for instance, the conversion of King Edwin

of Northumbria through the preaching of the missionary Paulinus, Bishop of York, and the miraculous

event surrounding the cowherd turned poet Caedmon. Bede’s ‘Death Song’ is the only extant

composition in English. It reads as follows:

Before the needful journey no one becomes

Wiser in thought than he needs to be

To think over, ere his going hence,

What of good and evil about his spirit

After his day of death, may be decided.

(Source: Kemp Malone)

Alcuin (735-804)

He was associated with the ecclesiastical school at York and later, in 782, became the cultural advisor

of Charlemagne. Along with several theological and philosophical tracts, Alcuin wrote a biography of

Willibrord, a missionary from Netherlands, and over three hundred letters that contain valuable

historical materials. His poem On the Mutability of All Human Affairs is a Latin Elegy on the

destruction by the Danish raiders of the famous Lindisfarne Abbey, famous seat of culture and

learning in northern England.

Caedmon and Cynewulf and Other Religious Poems

Unit I, Module III, p 3

Caedmon (died c.670)

Caedmon’s story has been well-documented by Bede at the end of his book Historia Ecclesiastica

Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People). Accordingly, it is told that he was an

unlearned man blessed by divine grace. He worked as a farmhand at the abbey at Whitby. At feasts

when everybody was encouraged to compose songs that would be accompanied by the harp, Caedmon

would feel extremely embarrassed. On one such occasion he left the table and went back to the stable

where he was employed for the night to look after the beasts. In his dream, ‘a certain man’ urged him

to sing about ‘the Creation of all things’. At this point Bede paraphrases Ceadmon’s hymn in Latin,

acknowledging humbly the fact that ‘This the general sense, but not the actual words that Caedmon

sang in his dream; for verses, however masterly, cannot be translated word for word from one

language into another without losing much of their beauty and dignity’.

Caedmon finally became a monk so that he could learn the scriptures and translate them to vernacular

poetry. Bede writes:

He sang first of the creation of the world and the beginning of the mankind, and all the

story of Genesis, that is the first book of Moses, and again of the Exodus of the people of Israel

from the land of Egypt and of the entrance into the promised land, and many of other tales of

holy writ... and of Christ’s incarnation, and of his passion, and of his ascent into Heaven; and of

the coming of the Holy Ghost, and the teachings of the apostles; and of the day of future

judgement and of the terror of punishment full of torment, and of the sweetness of the heavenly

kingdom he wrote many a lay; and also he wrought many other concerning divine benefits and

judgments.

It is doubtful whether Caedmon could actually accomplish such a massive scale of composition, for

no such canon survives. But the topics mentioned by Bede have definitely got poetic attention. In

1655 the Dutch scholar Junius published in Amsterdam ‘The Monk Caedmon’s Paraphrase of Genesis

Unit I, Module III, p 4

etc.’, based on an Old English manuscript containing Genesis, Exodus, Daniel and Christ and Satan.

Since they show some stylistic similarity with Caedmon’s style they are accepted as parts of the

Caedmonian cycle. There are certain features of this style which we shall shortly discuss but prior to

that let us take a look at the Hymn that was first composed by him.

Caedmon’s Hymn

In the margins of several of the 160 complete Latin manuscripts of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, the

Old English versions of Caedmon’s Hymn is noted down in chiefly two Anglo-Saxon dialects:

Northumbrian (earlier version) and West Saxon (later version). Here are the two versions of the poem

along with the translation done by Michael Alexander:

Northumbrian version West Saxon version

nu scylun hergan hefaenricaes uard Nu sculon herigean heofonrices weard,

metudæs maecti end his modgidanc meotodes meahte and his modgeþanc

uerc uuldurfadur swe he uundra gihwaes weorc wuldorfæder, swa he wundra gehwæs

ece drihten, or onstealde.

eci dryctin or astelidæ

he aerist scop aelda barnum He ærest sceop eorðan bearnum

heben til hrofe haleg scepen. heofon to hrofe, halig scyppend;

tha middungeard moncynnæs uard þa middangeard moncynnes weard

eci dryctin æfter tiadæ ece drihten, æfter teode

firum foldu frea allmectig firum foldan, frea ælmihtig

You may also listen to the Northumbrian and West Saxon version by following the links.

Translation:

Praise now to the keeper of the kingdom of heaven,

The power of the Creator, the profound mind

Of the glorious Father, who fashioned the beginning

Of every wonder, the eternal Lord.

For the children of men he made first

Heaven as a roof, the holy Creator.

Then the Lord of mankind, the everlasting Shepherd,

Ordained in the midst as a dwelling place

—The almighty Lord—the earth for men.

You have already read about the features of Old English poetry at the beginning of the Module II:

Elegies. Hence it would not be very difficult for you to understand the characteristic features of heroic

poetry in the above composition: for instance, the employment of poetical features caesura, variations,

alliteration and so on. He describes God as one would have described the overlord or king: the term

rices weard (keeper of the kingdom) becomes heofenrices weard (keeper of the kingdom of heaven).

Again, though short, thematically, the poem follows the Christian theological compositions of the

days. The poet refers to the concept of the Trinity through his variations: the might of the Lord/the

father (metudæs maecti), his thought (modgidanc), and his glorious work (uerc uuldurfadur). The

Unit I, Module III, p 5

poem also blends the eternal and physical

aspects of creation. Thus the genius of

Caedmon lies in transferring the entire range of

vocabulary from one sphere to the other.

The other poems of the Junius Manuscript that

are attributed to the Caedmonian cycle include:

Genesis, Exodus, Daniel and Christ and Satan.

The manuscript is divided into two books: the

In this illustration from the Caedmon

first contains verses related to the Old manuscript, an angel is shown guarding the

Testament; the second to Christ and Satan. gates of paradise, after Adam and Eve have

been expelled. Source: Web

Book I was done by one scribe towards the end

th th

of 10 century and early 11 , while Book II

was done by three scribes, after many years.

The manuscript has many lost pages, thus the poems are left incomplete. The Manuscript was

illuminated and in the first book, many pages are left blank which shows that the artists did not finish

the work. The first book is divided into 55 fits: 1-42 fits deals with Genesis, 42-50 with Exodus and

rest for Daniel. Modern philologists prefer to treat them. as three individual poems.

An example of a page of an illuminated manuscript: folios 9 verso and 10 recto of the Stockholm Codex Aureus,

Evangelical portrait of St Matthew. Source: Web

Genesis

The poem, consisting of 2936 lines, opens with a few lines in praise of God, and moves on to discuss

the happy lots of the angels in heaven. Next we are told of the discontent and rebellion of Satan and

his angels, God’s wrath, the creation of hell to house the rebels, their expulsion from heaven, and

God’s plan to make the world as a means to fill it with ‘better people’ (presumably the souls of the

blessed, the elect seed of Adam who are not yet created). Due to the loss of manuscript there have

been gaps in several parts of the text. Lines 235-851 do not belong to this poem and it is considered to

be an interpolation taken from a later poem on the same subject. This section, known as Genesis B,

which is composed in West Saxon dialect, deals with the temptation and fall of Adam and Eve and

shows greater poetic strength. The rest of the poem is known as Genesis A (lines 1-234 and 852-

2936). Genesis B is an interpolation. You will be interested to know that Milton had read the poem

and the theme of Paradise Lost is inspired by it.

Unit I, Module III, p 6

Exodus

The second poem in the book is the 591-lines long Exodus. The extant text (the battle scene being

lost) can be divided into the following parts: an introductory period on the Mosaic law (1-7); a brief

description of the life of Moses (8-29); a sketch of events in Egypt that led up to the departure of the

Hebrews (30-55); the march of the Hebrews to the Red Sea (56-134); the Egyptian pursuit (135-246);

the passage of the Red Sea and the destruction of the Egyptian army (247-515); conclusion (516-591).

The poet’s theme is not Exodus as a whole but the passage of the Red Sea by the Israelites under the

heroic leadership of Moses. There are brilliant instances of poetic achievement where Moses

encourages the Israelites to ‘make up their minds to perform deeds of valour’ (218 b). The poet gives

much space to the speech-making by his hero and the speeches are reported both in direct and indirect

discourse. In general, the poet follows the heroic tradition in which Moses is seen as an equivalent of

the Germanic king and his followers the worthy thanes. (Malone 64)

Daniel

The third and final poem of this manuscript is called Daniel which according to modern scholars

contains 764 lines. The scribe divides the text into six fits:

i. The first fit can be divided into two parts: an introduction to the Hebrew history down to

the war with Nebuchadnezzar and the story of the war due to which the Jew are held

captives by the Babylonian army and the three Hebrew children Hananiah, Mishael and

Azariah are given training for Nebuchadnezzar’s service. The second part is based on the

first chapter of Daniel where the biblical passages are paraphrased though much of the

work is left incomplete.

ii. This fit again falls into two parts: it begins with a condensed paraphrase of Daniel 2, in

which we learn about Nebuchadnezzar’s first dream and Daniel’s success in interpreting

it. This is followed by the story of the three children who refuse to worship the golden

image.

iii. This fit falls into three parts: first tells how the king throws the three children into fire and

they are saved by an angel; second the apocryphal prayer of Azariah; finally the repetition

of the first story of this section where the angel is shown to have come as an answer to

Azariah’s prayer.

iv. This fit begins with the apocryphal song of three youths in praise of God and is followed

by the paraphrase of the same story of the angel’s rescue.

v. This fit versifies Nebuchadnezzar’s second dream about the tree and Daniel’s

interpretation of it.

vi. The last fit versifies Daniel 5. The end is obscure as the last leaf of the manuscript is

missing.

Due to the difference of style the second and third part of the third fit is seen as an interpretation and

marked as Daniel B. This poem is identified as Azariah which can be found in the Exeter Book.

However, the entire poem is not taken, for the beginning is left out; it seems that the poet has taken

only that section which he liked the best.

Christ and Satan

The second book the Junius manuscript contains a 733 lines long poem, written around the ninth

century in East Anglian dialect. The poem is later titled as Christ and Satan. The text of the poem is

Unit I, Module III, p 7

divided into 12 fits, most of which are devoted to long laments of Satan after the loss of Heaven (parts

if the first, whole of second, third and fifth fit). The poem begins with the story of Creation, then

moves on to the fall of the angels, Satan’s lament, and ends with Christ’s harrowing of hell and

Ascension. The last fit talks about the doomsday and reminds the audience of the joys of those

redeemed. It concludes with Christ’s temptation by Satan, and Satan’s return to hell after his failure to

tempt Christ. The poem lacks chronological order for the last fit speaks about the event which took

place long before the Ascension. What we must understand is that unlike the other poems that we

have discussed, this one is not a mere paraphrase of the Bible. The author combines the lyrical,

dramatic and epic traditions to versify his knowledge of Christian theology. He has exercised freedom

of imagination for his aim was to speak about the punishments and rewards. Thus Christ’s temptation

comes at the end for it would instruct the readers to follow the example of Christ and believe in the

joys of heaven. Well-fit to this scheme is the character Satan: he is not a proud and angry leader but a

general broken by defeat—his defeat is to be read as a warning to us all.

Many modern scholars (one of them is Malone) believe that this poem is not composed by Caedmon.

The clerk who composed it knew both the styles of Caedmonian and Cynewulfian schools and

combined the best of the two styles in the poem.

There is another 349 lines-long poetic fragment, which is considered to be part of the Caedmonian

cycle, known as Judith that narrates the exploits of the Hebrew heroine who slew Holofernes, leader

of the Assyrian army encamped against her people. The figure of a female hero is rare and unique in

Old English poetry. However, this poem is found in MS Cotton Vitellius A xv, the codex that contains

Beowulf and many ascribe it to Cynewulf.

Cynewulf (c.750)

We have a list, a sermon, and two legends, i.e., saints’ lives as signed by a poet whose runic signature

tells that his name was Cynewulf. He was probably a Northumbrian, composing his poems around the

last quarter of eighth or early ninth century. Nothing else is known about his personal life.

Unit I, Module III, p 8

The Fates of the Apostles is a poem of 122 lines, recorded in the Vercelli Book. It contains a proper

list of the names of places and countries where the twelve apostles taught and died, and a poem in

which he speaks of the importance of prayers.

The Ascension, also known as Christ B, is of 427

lines and is recorded in the Exeter Book. Divided into

five fits the poem speaks about the Christ’s farewell

to his followers and his Ascension to heaven in the

first two fits and then move on to homiletic verses in

the next three fits talking about God’s greatest gift to

mankind, i.e., hope of salvation, six leaps of Christ

(conception, nativity, crucifixion, burial, descent into

hell, ascent to heaven), Solomon and Job’s song and

the fear of the doomsday. In this poem Cynewulf

versifies the conclusion of Gregory the Great’s

sermon on the ascension. The strength of the poem

lies in the freedom of imagination in depicting

matters of traditional wisdom.

Juliana, 739 line-long poem found in Exeter book is

also ascribed to Cynewulf. Owing to the loss of pages

of the manuscript two passages are supposed to be

missing: one that must have been between line

numbers 288 and 289 (folio no 70) and between 558

and 559 (folio no 74). The poem is divided into seven

fits and speaks of Juliana’s martyrdom. Juliana,

daughter of the pagan Africanus is betrothed to

Heliseus, an official under the Roman emperor,

Maximian, who persecuted Christians. Juliana refused

the match, and thus her father turned her over to

Heliseus for judgement. She was tortured but no harm

could be done to her. Even Devil failed to tempt her.

Finally, she was beheaded. The poet seemed to have

followed a Latin prose on St Juliana’s life but also

drew heavily from the heroic tradition of English

poetry.

North face of the Ruthwell Cross that

contains Dream of the Rood in Runic

script

Source: Web

Unit I, Module III, p 9

The final poem attributed to Cynewulf consists of 1321 lines and is called Elene. The poem is to be

found in Vercelli Book, divided into 15 fits. It depicts the legend of St Helen, mother of Constantine,

and her recovery of the Cross. The poem is not about her death as other legends are but about the

discovery. The poet uses the heroic tradition more freely in describing the voyage and battle. The last

fit seems to be autobiographical, where the poet, now old but divinely inspired speaks of the necessity

of prayers for the imminent Doomsday.

There are other poems like Andreas, Guthlac A and Guthlac B, The Phoenix, which are composed in

the Cynewulf’s style. They are a part of the Cynewulfian cycle. Dream of the Rood is also considered

to be a part of this cycle by many scholars. We shall read this poem in a greater detail.

Dream of the Rood

Dream of the Rood, or a Vision of the Cross, survives in Vercelli Book, folios 104 verso to 106 recto.

Parts of the poem are to be found in the shafts of the 8th century Northumbrian Ruthwell cross in runic

inscriptions. They correspond to lines 39-42, 44-5, 48-49, 56-59, 62-62 of the Vercelli book text.

The poem is riddilic (compare Exeter book riddle

30), penitential, eschatological and evangelical. It

has three central characters: the poet, the Cross,

Christ. The poet speaks in the first person to relate a

dream-vision (which would later become a recurrent

trope in medieval poetry), in which he slowly

unfolds the syllicre treow (a more wonderful tree),

the saviour’s tree. The narrative voice is taken over

by the cross itself who relates the story of its life,

how it was cut down and made into a cross and how

he bore the saviour, and became a close witness of

his Passion. This cross is Christ’s retainer, serving

its master just as a thane would serve his master and

also his bana or slayer, a role that is against the

conventions of the heroic society. This duality

constitutes the central paradox of the cross. Through

the vision of the cross the audience is made to

participate in the Crucifixion and therefore they get

a chance to repent for their ill-doings for which

Christ had paid with his blood. In order to stay clear

of the contemporary controversy regarding the

mortality and divinity of Christ, the poem focuses its

attention on the cross itself, the cross speaks of its

pain and suffering by witnessing the Crucifixion.

Like the Germanic lord, Christ lays his life for his

people, he voluntarily ascend the Cross and rests,

‘weary after the battle’. The Cross is then

discovered by Helena, Constantine’s mother and

West face of the Ruthwell Cross

becomes a symbol of faith and devotion.

Source: Web

The entire poem is interspersed with images of the

heroic society: the lord, the warriors and thane, and

Unit I, Module III, p 10

the battle. This poem is a splendid example of how the Anglo-Saxons reinterpreted Christianity in

accordance with the knowledge and custom of their heroic society.

Link to the text in Old English and to its translated version.

Now that you have read about the Caedmonian and Cynewulfian schools of poetry, can you make a

comparative study of the two? Think of the kind of themes they were taking up, their styles, and

how they treated the biblical knowledge.

Anglo-Saxon Prose: Alfred, Aelfric and Wulfstan

The literary prose in Old English is mostly made up of translations and paraphrases of Latin writings.

The English did not cultivate prose as a separate art from till they were acquainted with the Latin

literature. The models they followed were chiefly taken from the traditional genres like history,

philosophy and oratory. Epistles were also considered important. Prose was chiefly used for

educational and clerical purposes, for the common man verse remained the most acceptable art from.

We shall now take a brief look at the important prose-writers of the time.

Alfred (849-899)

In spite of the troublesome beginning of his reign and great efforts to establish peace in his nation,

Alfred was a patron of learning. His court housed notable scholars including Asser, who later became

Bishop of Sherbone. Asser wrote the biography of his King. He and other notable scholars helped the

king to make numerous translations from Latin into West Saxon. These translations include: Pope

Gregory’s Pastoral Care, a guide for the clergy; Orosius’ Universal History; Boethius’ Concerning

the Consolation of Philosophy, a dialogue of the early fifth century; and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History

of the English Nation. Although the prose would seem a bit stiff to the modern taste, it shows the zeal

of the king to revive and maintain learning among his people. He does not have any original

composition to his credit, but originality was not such an important issue in those days. However,

King Alfred also encouraged the composition of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle which recorded the

historical events from the earliest times to 1189, that is long after the death of Alfred.

Alfred’s compositions may lack the craftsmanship and training but it was his enthusiasm for learning

that changed the course of literary history in early England. He shows two major concerns through his

composition which are best reflected in the prefaces that he wrote to these volumes: first, importance

of translation of the Latin classics so that everyone could read it; second he wanted to revive the

culture of learning in both the clergy and the layman alike. His Preface to Gregory’s Pastoral Care

can serve as a good example. (Link to the Preface)

Aelfric (c.955- c.1020)

Aelfric composed two series of Homilies from late 980s to 995. He believed that his era was one of

affliction and turmoil and would lead to the end of the world. His desire was to create a body of

didactic prose in the vernacular. He translated the Heptateuch, i.e., the first seven books of the Bible

into Old English in several stages. He made the translation for the common man and thus left out large

portions of scriptural texts. His greatest achievement was the Catholic Homilies or Homiliae

Catholicae. This collection has 40 homilies and hagiographies in each series, it was meant to be used

Unit I, Module III, p 11

by the preachers for conducting church services. To this collection of homilies he added the Lives of

Saints or Passiones Sanctorum. He drew on the abundant stock of sermons and other religious

writings available in Latin; he made particular use of Gregory, Bede and Augustine. He treated his

material with greater freedom so as to mould it according to the needs of his contemporary audience.

Some of his passages are written in the rhythmic alliterative prose

Over thirty manuscripts of Catholic Homilies survive. In the Old English preface to the first series,

Aelfric demonstrates his discontent over the non-orthodox religious writings and speaks of the arrival

of the antichrist. He argues that these homiletic prose pieces would show the right path to the common

man by teaching them about the Christian virtues. (Link to the preface)

Wulfstan (died c. 1023):

Bishop of London and Worcester, and Archbishop of York, Wulfstan was a renowned homilist of his

time. His most famous sermon is called Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or Address to the English, the title of

which is in Latin but the text is written in Old English. The text is a bitter indictment in which the

author attributes the blame of Danish invasion to the moral degradation of the English people.

This powerfully written sermon, thundered from the pulpit by him or his colleagues, perhaps was

instrumental in bringing the English together against the Danes. Kemp Malone says: ‘The sermons of

Aelfric was meant to instruct; those of Wulfstan, to move; both homilists in the process produced

works of art unmatched in their respective kinds’. (Link to the sermon)

To sum up:

The Christian literature of the Old English period draws heavily on the Latin texts.

Since the inspiration was Latin religious texts, the first generation of writers composed

both in Latin and English, and their English works are, in many cases, lost.

The need for translation was realised by many scholars, Alfred is one of them. The aim

was to educate the mass in matters religious.

The religious verses was meant to inspire and educate; the poets composed in a style that

would impress the audience of a society rooted in heroic tradition, both in terms of poetic

conventions and social ideologies.

The prose writers’ aim was educational. The religious and the national causes merged quite

well and they were used to unite the British against the Danish invasion. Perhaps, this was

also a reason why the Danes destroyed so many churches.

Unit I, Module III, p 12

You might also like

- The History of the English Church and People (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe History of the English Church and People (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (241)

- Anglo-Saxon Literature & Old English PeriodDocument6 pagesAnglo-Saxon Literature & Old English PeriodPI C NaungayanNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Literature, Anglo-SaxonDocument9 pagesGroup 6 Literature, Anglo-SaxonZahara Muthia 649No ratings yet

- Old English Literature11Document34 pagesOld English Literature11ptxNo ratings yet

- History of Old English LiteratureDocument7 pagesHistory of Old English LiteratureOfik Taufik NNo ratings yet

- Our Catholic Heritage in English Literature of Pre-Conquest DaysFrom EverandOur Catholic Heritage in English Literature of Pre-Conquest DaysNo ratings yet

- Specimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets, CompleteFrom EverandSpecimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets, CompleteNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon History: The Roots of English LiteratureDocument18 pagesAnglo-Saxon History: The Roots of English LiteratureYouniverseNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon LiteratureDocument8 pagesAnglo-Saxon Literaturecristinadr86% (7)

- Old English Literature: Literary BackgroundDocument4 pagesOld English Literature: Literary BackgroundJelly Mae TaghapNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon Literature HistoryDocument17 pagesAnglo-Saxon Literature HistoryLookman AliNo ratings yet

- Old English LiteratureDocument68 pagesOld English Literaturedenerys2507986No ratings yet

- Old English IntroDocument26 pagesOld English IntroDan100% (1)

- Anglo-Saxon Literature: From Caedmon's Hymn to the Anglo-Saxon ChronicleDocument12 pagesAnglo-Saxon Literature: From Caedmon's Hymn to the Anglo-Saxon ChronicleAlejandroNo ratings yet

- The British Edda: The Great Epic Poem of the Ancient Britons on the Exploits of King Thor, Arthur or Adam and his Knights in Establishing Civilization Reforming Eden & Capturing the Holy Grail About 3380-3350 B.C.From EverandThe British Edda: The Great Epic Poem of the Ancient Britons on the Exploits of King Thor, Arthur or Adam and his Knights in Establishing Civilization Reforming Eden & Capturing the Holy Grail About 3380-3350 B.C.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Unit 1Document9 pagesUnit 1jesusNo ratings yet

- Old English LiteratureDocument12 pagesOld English LiteratureAigul AitbaevaNo ratings yet

- Delphi Complete Works of the Venerable BedeFrom EverandDelphi Complete Works of the Venerable BedeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Old English LiteraturDocument6 pagesOld English LiteraturTerri BatesNo ratings yet

- Old EnglishDocument3 pagesOld EnglishPedro Henrique P. RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Old EnglishDocument7 pagesOld EnglishParlindungan Pardede100% (1)

- Wide As the Waters: The Story of the English Bible and the RevolutionFrom EverandWide As the Waters: The Story of the English Bible and the RevolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Rise of English Literary Prose (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe Rise of English Literary Prose (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- Old English LiteratureDocument5 pagesOld English LiteratureAlinaIoschiciNo ratings yet

- From Chaucer to Tennyson With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsFrom EverandFrom Chaucer to Tennyson With Twenty-Nine Portraits and Selections from Thirty AuthorsNo ratings yet

- Resumen LiteraturaDocument5 pagesResumen LiteraturaFlorencia RoldánNo ratings yet

- BRITISH LITERATURE PERIODSDocument13 pagesBRITISH LITERATURE PERIODSmrNo ratings yet

- The Earliest English Literature RevisedDocument15 pagesThe Earliest English Literature Revisedapi-249904851No ratings yet

- Anglo-Saxon ChronicleDocument4 pagesAnglo-Saxon ChroniclePedigan, Geelyn N.No ratings yet

- Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum: What Is Prose?Document3 pagesHistoria Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum: What Is Prose?Dian NurfitrianaNo ratings yet

- Лекция 1Document7 pagesЛекция 1Меруерт АхтановаNo ratings yet

- History of English Literature in Ancient PeriodDocument7 pagesHistory of English Literature in Ancient PeriodM Hisyam AlfalaqNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Linguistic and Cultural Strands of Early Medieval British LiteratureFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Linguistic and Cultural Strands of Early Medieval British LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Anglo-Saxon PoetryDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Anglo-Saxon PoetrySnow FlowerNo ratings yet

- History of the English People, Volume V Puritan England, 1603-1660From EverandHistory of the English People, Volume V Puritan England, 1603-1660No ratings yet

- Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James BibleFrom EverandPen of Iron: American Prose and the King James BibleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Anglo-Saxon's Literature (Old English)Document2 pagesAnglo-Saxon's Literature (Old English)vareenNo ratings yet

- HEL Module 2Document21 pagesHEL Module 2Ma. Aurora Rhezza GarboNo ratings yet

- BeowulfFrom EverandBeowulfMarc HudsonRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4424)

- Survey of English and American Literature (Body)Document7 pagesSurvey of English and American Literature (Body)Jinky JaneNo ratings yet

- British LiteratureDocument60 pagesBritish LiteratureJorge HardyNo ratings yet

- Specimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets, Volume 1From EverandSpecimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets, Volume 1No ratings yet

- The Homilies of the Anglo-Saxon Church Containing the Sermones Catholici, or Homilies of Ælfric, in the Original Anglo-Saxon, with an English Version. Volume I.From EverandThe Homilies of the Anglo-Saxon Church Containing the Sermones Catholici, or Homilies of Ælfric, in the Original Anglo-Saxon, with an English Version. Volume I.No ratings yet

- British LiteratureDocument108 pagesBritish LiteratureAPURBA SAHUNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 5 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesDocument25 pages1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 5 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesRitchie FamarinNo ratings yet

- Trinity United Church of Christ BulletinDocument24 pagesTrinity United Church of Christ BulletinWorlee GloverNo ratings yet

- (A. Guillaume) Studies in The Book of Job, With ADocument162 pages(A. Guillaume) Studies in The Book of Job, With AIgnacio de la CruzNo ratings yet

- Judaism Part 2Document3 pagesJudaism Part 2Trenton JeyaseelanNo ratings yet

- Doubleportioninheritance Blogspot Com 2011 07 Does-NameDocument15 pagesDoubleportioninheritance Blogspot Com 2011 07 Does-Nameapi-231781675100% (1)

- "Life in A Lions' Den" (Daniel 6:1-28) : CharacterDocument9 pages"Life in A Lions' Den" (Daniel 6:1-28) : CharacterNamesNo ratings yet

- Over 200 Bible FactsDocument15 pagesOver 200 Bible FactsTimme de Vu100% (4)

- Daniel's Seventy Weeks Vision ExplainedDocument19 pagesDaniel's Seventy Weeks Vision ExplainedNorbert AMANYNo ratings yet

- Apocalyptic in OTDocument36 pagesApocalyptic in OTkelt35No ratings yet

- Old Testament Heroes Activity PackDocument27 pagesOld Testament Heroes Activity PackBeryl ShinyNo ratings yet

- 12 Most Inspiring Leadership Lessons From Bible CharactersDocument4 pages12 Most Inspiring Leadership Lessons From Bible CharactersAie Gapan CampusNo ratings yet

- Matthew's Gospel as the Hebrew GospelDocument752 pagesMatthew's Gospel as the Hebrew Gospelsommy55No ratings yet

- Easy Round Bible Quiz 2Document10 pagesEasy Round Bible Quiz 2Bonskie JaranillaNo ratings yet

- Daniel commentary highlights key interpretationsDocument505 pagesDaniel commentary highlights key interpretationsJon Stavros0% (1)

- The Book of DanielDocument56 pagesThe Book of DanielA. HeraldNo ratings yet

- La Gran TribulacionDocument13 pagesLa Gran TribulacionByron Enrique Mansilla RodriguezNo ratings yet

- De Septem Secundeis by J TrithemiusDocument17 pagesDe Septem Secundeis by J TrithemiuskrataiosNo ratings yet

- John Nevins Andrews - The Three Angels of Revelation 14Document90 pagesJohn Nevins Andrews - The Three Angels of Revelation 14Francisco HigueraNo ratings yet

- An Outline of The Prophetic Book of DanielDocument5 pagesAn Outline of The Prophetic Book of DanielGreg KawereNo ratings yet

- Daniel PPT Chapt 02.18390123Document95 pagesDaniel PPT Chapt 02.18390123mensarNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Nebuchadnezzar Ii: Exhibit 2Document4 pagesAn Introduction To Nebuchadnezzar Ii: Exhibit 2Herbert YonathanNo ratings yet

- Khris Vallotton Developing A Supernatural LifestyleDocument337 pagesKhris Vallotton Developing A Supernatural LifestyleCristian Catalina83% (6)

- Book of DanielDocument6 pagesBook of DanielKian LaNo ratings yet

- Daily Bible Study DanielDocument17 pagesDaily Bible Study DanielYunzhiTristaNo ratings yet

- Daniel Fast CalendarDocument2 pagesDaniel Fast Calendarwillisjt75% (4)

- 3rd Quarter 2016 Cornerstone Connections IntroductionDocument4 pages3rd Quarter 2016 Cornerstone Connections IntroductionRitchie FamarinNo ratings yet

- Apocalypse ThenDocument371 pagesApocalypse ThenAlexandru Agarici100% (2)

- Daniel Small Group Bible StudyDocument14 pagesDaniel Small Group Bible StudyTimmy GraceNo ratings yet

- The New Age of Disgrace ExposedDocument16 pagesThe New Age of Disgrace ExposedCharlie100% (2)

- Daniel Summary and Symbolism - No FormattingDocument30 pagesDaniel Summary and Symbolism - No Formattingapi-303640034100% (2)