100% found this document useful (1 vote)

653 views6 pagesReliability and Validity

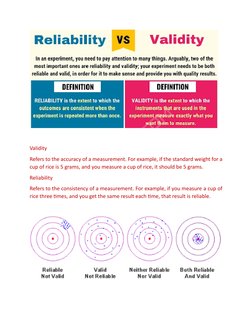

Validity and reliability are important concepts in research. Validity refers to how accurately a study measures what it intends to, and there are several types including content, construct, and criterion validity. Reliability indicates whether a study's methods can produce consistent results, and types involve test-retest, internal consistency, and inter-rater reliability. Both concepts are crucial for ensuring research quality and accuracy of findings.

Uploaded by

Shereen shaikhCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

100% found this document useful (1 vote)

653 views6 pagesReliability and Validity

Validity and reliability are important concepts in research. Validity refers to how accurately a study measures what it intends to, and there are several types including content, construct, and criterion validity. Reliability indicates whether a study's methods can produce consistent results, and types involve test-retest, internal consistency, and inter-rater reliability. Both concepts are crucial for ensuring research quality and accuracy of findings.

Uploaded by

Shereen shaikhCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

- Reliability vs Validity Overview

- Validity

- Reliability