Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Voyles-Cardinal Numerals in Pre - and Proto-Germanic 1987

Uploaded by

Pawel OzzkowskiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Voyles-Cardinal Numerals in Pre - and Proto-Germanic 1987

Uploaded by

Pawel OzzkowskiCopyright:

Available Formats

The Cardinal Numerals in Pre-and Proto-Germanic

Author(s): Joseph Voyles

Source: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology , Oct., 1987, Vol. 86, No. 4 (Oct.,

1987), pp. 487-495

Published by: University of Illinois Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27709904

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Journal of English and Germanic Philology

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of English and Germanic Philology?October

? 1987 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

THE CARDINAL NUMERALS IN PRE- AND

PROTO-GERMANIC

Joseph Voyles, University of Washington

In the following article I shall reconstruct what I shall argue are the

most probable forms of the late Indo-European or immediately pre

Germanic cardinal numerals. My reconstructions will be based on the

forms of these numerals as they occur in the earliest attested Ger

manic languages, namely Gothic, Old Icelandic, Old English, Old Fri

sian, Old Saxon, and Old High German.1 As my methodological

framework for reconstructing the pre-Germanic forms of these nu

merals I make the following three basic assumptions.

First, I assume that cardinals can influence other cardinals in the

series by a kind of frequently observed paradigmatic pressure. Ex

amples of this type of change are found in many Indo-European lan

guages, such as Russian devjat' '9' with its initial [d] replacing earlier

[n] (*nevjat') on the model of desjaf '10'. Another and perhaps more

familiar example of such paradigmatic change?but here in the or

dinal series?is the pronunciation by some American speakers of sec

ond as [sek^nt] with word-final [t] carried over from first.

Next, I assume that cardinals usually?and apparently invariably as

far as the Germanic languages are concerned?determine the form

of the ordinal numerals and not the other way around. This seems to

have been always the case in the attested instances found among the

Germanic languages: e.g., ModEng. tenth instead of the phonologi

cally regular and earlier tithe (whence tithe) from the cardinal ten +

the ordinal suffix -th; and ModHG zweit '2nd' instead of earlier ander

from the cardinal zwei + the ordinal suffix -t. There exists to my

knowledge no clear instance in the history of any of the Germanic

languages of an ordinal numeral determining the form of a cardinal.2

1 Any of the standard handbooks suffice for the attestations. I have relied for Gothic

on Wolfgang Krause, Handbuch des Gotischen (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1953); for Old Ice

landic on Adolf Noreen, Altnordische Grammatik (University: Univ. of Alabama Press,

1970); for Old English on Alistair Campbell, Old English Grammar (London: Oxford

Univ. Press, 1964); for Old Frisian on Walther Steller, Abriss der Altfriesischen Grammatik

(Halle [Saale]: Max Niemeyer, 1928); for Old Saxon on Ferdinand Holthausen, Alt

s?chsisches Elementarbuch (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1900); and for Old High German on

Wilhelm Braune, Althochdeutsche Grammatik, ed. Hans Eggers, 13th ed. (T?bingen: Max

Niemeyer, 1975).

2 This includes the case of OI fern '5' instead of the phonologically regular but non

occurring fif. The form/<?m is often considered derived from the earlier ordinal *ftmft

487

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

488 Voyles

Third, I assume the usual and familiar phonological changes from

Indo-European into Germanic, most of which I shall not need to for

mulate here. These are the following: the First Sound Shift (hereafter

abbreviated ist ss), whereby the Indo-European obstruent consonants

became their Germanic reflexes (p, bh, b?> f, b, p, etc.); Verner's Law

(hereafter verner), whereby voiceless obstruents are voiced if imme

diately preceded by an (Indo-European) unstressed syllable; the shift

from Indo-European to Germanic stress (str shift), and the deletion

of word-final nasal consonants if preceded by a Germanic unstressed

syllable (which I abbreviate as nas dele). Examples of this latter

change are the IE ace. sg. * dh?ghwom 'day', eventually Gmc. * daga and

the IE gen. pi. * dhoghw?m, Gmc. * dag?. Another of these changes is

that of the Indo-European syllabic r?sonants [1, m, n, r] to Germanic

[ul, urn, un, ur] (which I shall label syl res). And another change

often referred to in the literature but rarely explicitly formulated is

the deletion of the coronal and nonstrident consonants [d, d, t, 6]

word-finally after a Germanic unstressed syllable. Examples of this

change (hereafter cor c dele) are the IE 3 sg. pst. sub. * bh?r?t 'carry',

Gmc. * b?r?, or the IE 3 pi. sub. * hh?r?nt, Gmc. * b?r?n. This latter form

shows that nas dele cannot precede cor c dele but must either follow

or be contemporaneous with it. Another of these changes is that of

[gw] (from IE [kw] by verner or from [ghw] by the ist ss) to [w] in some

environments and to [g] and [gw] in others. The precise conditioning

of the change need not concern us here;3 I shall refer to it as gw-to

w. Finally, I shall assume a rule of nasal assimilation (nas assim) for

both Indo-European and Germanic, whereby a nasal consonant was

assimilated to the place of articulation of a following obstruent conso

nant within a morpheme, i.e., if not immediately followed by a mor

pheme boundary. Instances of this rule are the occurrence of forms

like IE *bhendh- 'tie' and Gmc. * bind- 'tie', forms like *bhemdh- or

* bimd- being impossible.

Given the above assumptions on reconstructing and the changes

from Indo-European to Germanic?and keeping in mind the numer

als as they are attested in the Germanic and in the other Indo

with subsequent reduction of the consonant cluster to *fimt-. But this is not necessarily

the correct account since the consonant cluster could also and just as easily have been

simplified from the cardinal *fimftehan '15', later fimt?n.

3 Varying versions are found in Joseph Voyles, "Simplicity, Ordered Rules, and the

First Sound Shift," Language, 43 (1967), 636-60; and in Elmar Seebold, "Die Ver

tretung idg. gvh im Germanischen," Zeitschrift f?r vergleichende Sprachforschung, 81

(1967), 104-33.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Cardinal Numerals in Pre- and Proto-Germanic 489

European languages?I posit the following as the most likely forms of

the pre-Germanic cardinals. I cite alongside my reconstructed forms

the corresponding ones of Gothic, the earliest extensively attested

Germanic language. In some instances where Gothic may not reflect

some particular aspect of the earlier stage, I shall cite forms from one

of the other early Germanic languages:

V * ?inos with sg. adj. endings, Go. ains.

'2' * dw?i with pi. adj. endings, Go. twai.

'3 * tr?jes with pi. i-class noun endings, Go. preis; possibly also with

pi. adj. endings as in the OE mase. nom. pi. prie.

'4' *pekw?r and * petw?r, probably in free variation, and the ablaut

ing * pet?r-, which last allomorph seems to have occurred only in com

pounds. The latter two occur by the ist ss and verner as Go. fidwor

and in the Go. compound adj. fidur-dogs '4-day'. (Another reflex of

* pet?r- is probably the Old Icelandic inflected numeral fj?rir '4', which

took on pi. adj. endings.) The other Germanic languages show re

flexes of*pekw?r, which by the ist ss and verner would appear at first

as *fegw?r and then later by gw-to-w and str shift as *f?w?r, even

tually as OE f?ower, OF fiower and for, OS fiuwar and later for, and

OHG feor.

'5' * p?mpe, Go. fimf

'6' * s?ks, Go. saihs.

'7' * sepnt, Go. sihun. The historical derivation is as follows: * sepnt

(ist ss, verner, syl res) ?-? * seb?nd (str shift) ?? *s?bund (cor c

dele) ?? * s??un (eventually) ?> Go. sihun.

'8' * okt?u, Go. ahtau.

'9' * newnt, Go. niun.

'10' * d?knt, from which Go. taihun; and possibly in free variation

*d?kont, from which OS tehan (not **tehuri) and OHG zehan (not

**zehuri)?where the double asterisk does not mean a reconstructed

form, but an incorrect or nonoccurring one. The derivation of the

suffix -un is like that on '7': * d?knt (ist ss, verner, syl res) ?? * t?hund

(cor c dele) ?? * t?hun. The suffix *-ont, which we assume was taken

from '11', may not have occurred on '10' until Germanic times.4

'11' * oin '1' + the verb * lip- 'remain'.5 The verb could optionally

take its pr?s. part, ending * -ont, or the *-nt from '10', or no ending at

all. Hence three forms for '11' are attested: OE endlefan from the ante

4 Another possibility suggested by Oswald Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European

System of Numbers (Heidelberg: Carl Winter, i960), p. 101, is that *-ont came from the

suffix in what he posits as '30' * trlkonta, '40' * kwetwfkonta, etc.

5 Listed under * leip- in Julius Pokorny, Indogermanisches Etymologisches W?rterbuch

(Berne and Munich: Franke, 1959). The ablaut form of the verb which I posit here is an

"aorist-present."

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

49? Voyles

c?dent with * -ont, O? ellifu from that with * -nt, and OHG einlif from

* oin + lip with no ending. The stress configuration was, in view of the

OHG form, probably * ?in + lip, i.e., the typical compound pattern

with primary stress on the first constituent and secondary on the sec

ond. This is then why verner did not apply to produce OHG * * einlib.

'12' * dw? '2' + * lip, Go. twalif.6

'13' through '19', the respective numeral + *d?knt or *d?kont 'io',

Go. pritaihun '13', OHG dr?zehan '13'.

'20' through '60', the respective numeral followed by the mase,

noun * dek-'io' (either an i-class or a u-class noun, it is not clear which;

perhaps the class membership was in free variation between the two).

E.g., late pre-Gmc. IE * dwoi * dekewes '2 10s, i.e., 20', early Gmc. * twai

* tegewez, Go. twai tigjus (the noun here in the u-class), OE tw?ntig,

OHG zweinzig or zweinzog.7 A similar formation is OI prir tigir '30' (the

noun here in the i-class). Szemer?nyi notes that these particular for

mations do not appear to correspond to the original Indo-European

system.8 This would mean that this construction was later, pre

Germanic Indo-European or perhaps not formed until early Ger

manic times.

'70' through '90', this construction is formed from a numeral nomi

nalized into an i-class noun with the frequently occurring IE suffix

*-t. This i-class noun was in the gen. pi. and was followed by the neut.

sg. noun *kntom. The latter noun means 'a basic 10-ness', i.e., 'a

10-ness of 10s = 100' in a decimal system or 'a 10-ness of 12s = 120' in

a duodecimal system?of which more directly. An instance of this

construction would be '70', * sepnt -f * t + gen. pi. *-ora.9 Some attested

reflexes are Go. sibuntehund and, with some modifications which we

shall consider later, OE hundsiofontig, OS antsibunta, and OHG sibunzo.

The 7o-through"90 construction, like that of 20-through-6o noted

above, does not appear to correspond to the original Indo-European

6The Go. dat. pi. twalibim, which has undergone verner, instead of **twalifim

probably indicates that the stress had shifted to the initial syllable in East Germanic

earlier than elsewhere in Germanic. This suggestion has been previously made by

scholars such as Hermann Hirt and Eduard Prokosch.

7 The OHG suffix -zog was formed by contamination from -zig with -zo, the latter

from forms like OHG sibunzo '70' discussed below.

8Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 27.

9The gen. pi. of Gothic nouns of this class is -e [-?] from a putative *-?m instead of

the expected -0 [-0] which occurs in the other Germanic languages, hence Go. dage 'of

days' versus OS dago 'of days'. The provenience of the Gothic ending has long consti

tuted a problem in historical Germanic linguistics, which, however, is only peripheral to

our concerns here. We shall assume that the Indo-European ending was *-?m, that of

Germanic *-?, and that Go. -e represents an innovation. See on this question Asbury

Wesley Jones, "Gothic Final Syllables" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill, 1979), pp. 64?73.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Cardinal Numerals in Pre- and Proto-Germanic 491

system. Hence it was either late pre-Germanic Indo-European or per

haps not even formed until Germanic times.10

'ioo' *kntom, a neut. o-class noun meaning 'a basic 10-ness', which

would mean 'a 10-ness of 10s or 100' in a decimal system or 'a 10-ness

of 12s or 120' in a duodecimal one. Both types of systems seem to have

existed in the early Germanic, indications of which being OS hund 'a

10-ness of 10s = 100' in a decimal system and OI hundrap 'a 10-ness of

12s = 120' in a duodecimal one. A further indication of the potential

ambiguity of *hund between '100' and '120' is attested in the Gothic

Bible in the construction fimf hundam taihuntewjam bropre (I Cor.

15:6), i.e., '5 hundreds, ten-based, of brothers' = '500 brothers'. Here

the compound adj. taihun + tewjam modifying hundam (both in the

dat. pi.) means '10-ordered' or '10-based' and is added to disambigu

ate between that and 12-based hundam, which would presumably have

been described in Gothic with the adj. * twaliftewjam.

'200' through '900', the respective numeral followed by * kntom in

the neut. pi., i.e., * knt?; Go. twa hunda '200'. Of course in a 12-base

system as in Old Icelandic, tvau hundrup means '240'.

'?ooo', *t?s + *knt + j?-class noun endings, Go. pusundi.

The reconstructions given above differ in a least four major re

spects from those usually found in the literature.11 Here I shall argue

that these differences constitute more reasonable hypotheses than

those proposed up to now.

The first of these differences concerns the numerals '4' and '5'.

They are usually reconstructed as something like *kwetw?r and

*penkwe.12 These forms may well have occurred as such in earlier

10 In view of the familiar Indo-European morphophonemic rule whereby the se

quence lal was realized as [ss] as in the past part. *wit+t+os 'known' ?> *wissos, even

tually ModHG (ge)wiss 'certain', a sequence like * sepnt+t+?m would probably have been

realized in late Indo-European times as *sepnss?m, eventually Gmc. * sebuns? instead of

* sebunt?. The exclusive occurrence of forms obviously derived from the latter possibil

ity may well indicate that the 7o-through~90 construction was formed in early Germanic

times and as such after the cor c dele change, i.e., as Gmc. *sebun+1+ ?.

11 Most of these are summarized in Chapter 2 of Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo

European System of Numbers. Two more recent studies, which in my opinion have added

little to the discussion, are Gernot Schmidt, "Zum Problem der germanischen Dekaden

bildung," Zeitschrift f?r vergleichende Sprachforschung, 84 (1970), 98?136; and Rosemarie

L?hr, "Die Dekaden '70-120' im Germanischen," M?nchner Studien zur Sprachwissen

schaft, 36 (1979), 59~73- Schmidt (p. 119) posits a Gmc. *-t?-hun?a from an IE *-kmte

followed by a mysterious *-de- which was purportedly "eingef?hrt im Zuge einer Ver

deutlichung des Dekadensystems," while L?hr (p. 64) maintains ". . . so l??t sich

got. -te- . . . m?helos auf den Instrumental der Erstreckung uridg. *deh{ (lat. de 'von

weg . . .') zur?ckf?hren. . . ." Since neither of these theories seems to have found much

resonance, I shall below confine my attention to Szemer?nyi's views.

12 As in Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 92.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

492 Voy les

Indo-European. But the reconstructive axioms enumerated above

have led me to posit as the immediately pre-Germanic forms the free

variants *pekw?r and * petw?r '4' and *p?mpe '5'. These latter three

forms probably arose from the former in accordance with the first

assumption above of the possibility of paradigmatic pressure among

numerals in a series. Thus the word-initial *p of * p?nkwe was transmit

ted to * kwetw?r to give * petw?r. The word-internal * kw of * p?nkwe was

taken on optionally by * petw?r to give *pekw?r alongside earlier and

still extant * petw?r. And still later the * kw in * p?nkwe was replaced by

its word-initial *p to give * p?mpe, whence eventually Gmc. *femf.15

The second difference concerns the forms for '7' and '9', which are

usually reconstructed as IE * septm and *newm.14 Given such well

established changes from Indo-European into Germanic as the ist ss,

SYL res, and nas dele referred to earlier, these two forms would have

to have become Gmc. * * seftu and * * newu and Go. * * sift and * * niwu

instead of sibun and niun. Szemer?nyi, in addition to others, recognizes

the problem in the case of'7', though not of '9'.15 He reconstructs the

former as derived from the Indo-European ordinal * septmtos '7th'.

According to this theory, * septmtos first became * sepmtos by a dissimila

tory loss of the first * t in the sequence, which latter form then devel

oped regularly into Gmc. *sebundaz by the ist ss and verner. Finally,

this Germanic ordinal * sebun+daz constituted the analogical basis for

the reformation of the new cardinal number * sebun.

There are at least two reasons why this account is suspect. First, a

dissimilatory loss of the first of two Indo-European * ?'s in a sequence

is otherwise unattested as a development into Germanic. Hence a

Gothic form like gamaindups 'community' is attested, the suffix being

from an IE *-tut with two consecutive * ?'s. Second, in accordance with

the second axiom on reconstructing given above, cardinal numerals

seem invariably in the history of the Germanic languages to have in

fluenced the form of the ordinals and not the other way around.

Hence I reject this account and posit the late Indo-European proto

forms as * sepnt and * newrit. As in the case of '4' and '5' discussed

above, these may well have developed by paradigmatic pressure from

the earlier forms * septm and * newm. That is, the *-nt on * d?knt '10'

was also affixed to * newm to give * newnt; and these forms then pres

sured a change from * septm to * sepnt. These forms then developed

15 Another possibility of accounting for the Germanic form for '5' would be to posit

as its immediate antecedent in fact *p?nkwe, which by the ist ss became *f?mxwe and

ended up as Gmc. *f?mfe by some sort of phonological change by which *xw became */

in this?and perhaps other?environments.

14 As in Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 92.

15Szemer?nyi's discussion is in Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 35.

See also Eric Hamp, "The Anomaly of Gmc. '7'," Word, 8 (1952), 136-40.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Cardinal Numerals in Pre- and Proto-Germanic 493

regularly into Gmc. *sebun and * newun by the ist ss, verner, str

shift, syl res, and finally cor c dele and nas dele?the latter two

changes in the order given.

The third difference of my reconstructions from the traditional

ones constitutes only a minor innovation in that I pattern the '10' after

some suggestions of Szemer?nyi: "The fact that '10' appears, in some

areas at any rate, to derive from * dekm is easily explained on the as

sumption that * dekm is the preconsonantal sandhi-variant of * dekmt

[the original form]. . . ,"16 I modify Szemer?nyi's reconstruction to

* d?knt with * n instead of * m by dint of the IE nas assim rule noted ear

lier. This form then developed to Gmc. * tehun regularly and by much

the same route as '7' and '9' described in the preceding paragraph.

The fourth difference is the reconstruction of the formations for

'70' through '90' as they occurred in early Germanic and perhaps in

pre-Germanic as well. I have reconstructed them as consisting of an

abstract noun formed with the suffix *-t and in the gen. pi. This noun

was followed in turn by a noun meaning 'a basic 10-ness', e.g., Gmc.

* sebunt? * hunda = 'of 7s a 10-ness' = 'a 10-ness of 7s' = '70'. This

diverges totally from Szemer?nyi's account, whereby forms like IE

*penkw?kont- '50' and * okt?kont- '80' developed into Gmc. * femf?xanp

and *axt?xanp-.17 Then, according to Szemer?nyi, "The divergence

between E Gmc. [as in Go. sihuntehund '70'] and W Gmc. [as in OHG

sihunzo '70'] is merely due to the fact that the inherited system, with

-?- in '50' but -?- in '80', and no other juncture vowel between '40' and

'90', gave two possible ways of realization: either the extension of -?

(Gothic) or that of -0- (W Gmc.)"18?which difference, it should be

noted, is only coincidentally paralleled by the vowels of the gen. pi.:

Go. dage 'of days' versus OHG tago 'of days'. This striking coincidence

alone renders Szemer?nyi's account suspicious.

Szemer?nyi himself realizes first, that there are severe problems

with his theory and second, that the most likely competitor is one like

mine wherein the first constituent of the construction is a gen. pi.

noun. Accordingly, Szemer?nyi defends his own account while at the

same time attempting to discredit any possible "gen. pi." theory.

It should at this point be noted that a version of a gen. pi. theory

different from mine has already been proposed by Brugmann.19 His

theory differs from mine, however, in that he posits as the Indo

16 Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 68.

17 As outlined in Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, esp.

PP- 33-44

18 Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 36.

19 Karl Brugmann, "Die Bildung der zehner und der hunderter in den indo

germanischen sprachen," Morphologische Untersuchungen, 5 (1890), 1?61 (Nachtrag

138-44), Leipzig.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

494 Voyles

European antecedent of the Germanic suffix *-t a *-d as in Gk. dekad

'decade', which has been justifiably rejected since the *-d in this func

tion does not seem to occur anywhere in Indo-European outside of

Greek. But a *-d would have occurred as Gmc. *-t by the ist ss. Under

my theory, the Germanic nominalizer *-? was inherited unchanged

from the frequently attested IE *-?. The suffix came unchanged into

Germanic probably because of its occurrence in environments such as

Gmc. *geft- 'gift' (from IE *ghebh + t) or * anst- 'favor' (from IE

*ons+t), where it would not have been affected by the ist ss. This

suffix is otherwise frequently attested in Germanic in its unshifted

form as an i-class nominalizer (e.g., Go. andanum-\-1+s 'act of taking

up') and in other Indo-European languages as well, such as Gk. krisis

'crisis, decision' from earlier *kri+t+is. The suffix was also used in

other Indo-European languages to form i-class nouns derived from

numerals such as Skt. naviti 'a 9-ness'. And it is clearly productive in

Old Icelandic to form numerical nouns like tylft '12-ness, a dozen' or

fimmt 'a 5-ness'.20

One argument Szemer?nyi adduces against the gen. pi. theory is

that the word-final -a in a form like OS sibunta '70', under my theory

from earlier * sibunto and still earlier * sibunto (*hund), could not be

the remnant of a gen. pi. ending because that would be -0 in Old

Saxon as in dago 'of days'.21 Szemer?nyi's view is wrong here, since

word-final and unstressed OS loi could, particularly if the immedi

ately preceding syllable was unstressed as in a form like * sibunto,

often be realized as [a].22

A particularly troublesome phenomenon for Szemer?nyi's theory is

the occurrence of forms like OS antsibunta '70' and OE hundseofontig

'70' in which the first syllables ant- and hund- are clearly reflexes of

*hund, which in these words has been preposed. This preposing of

* hund needs explaining. Szemer?nyi tries to account for it as an at

tempt by speakers to disambiguate '70'?* sefonta * hund according to

him?from '70 hundreds', i.e., '7000'.23 This is improbable, first be

cause the two numbers are far enough apart so that no ambiguity was

ever likely to arise, and second, because any such attempt to resolve

20 Szemer?nyi (Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 106) in an attempt to

argue against the productivity of this suffix as a numerical nominalizer in Germanic

notes that Old Icelandic fimmt ". . . does not mean 'a group of five' but only 'summons

(with a notice of five days)'. . . ." This of course only shows that these numerical nouns

formed with the / suffix could, like any other nouns, be used metaphorically and not

that the formation was nonproductive.

21 Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 31.

22 See on this Joseph Voyles, "The Phonology of Old Saxon," Parts 1 and 2, Glossa, 4

(1970), 123-60, and 5 (1971), 3-31.

23 Szemer?nyi, Studies the in Indo-European System of Numbers, p. 38.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Cardinal Numerals in Pre- and Proto-Germanic 495

the ambiguity by preposing * hund to form *hund *sefonta would have

brought it close to ambiguity with '170'. A more likely resolution of

such a purported ambiguity would have been the total deletion and

not the preposing of *hund.

Yet such preposing is easily accounted for under a gen. pi. theory. A

genitive construction like *sebunto~ * hunda '70' could easily occur, as

do other genitive constructions, with its genitive constituent post

posed as * hunda * sebunt?, whence the later Old Saxon and Old En

glish forms.

Finally, under any gen. pi. theory a question of semantics arises as

to how Gmc. *hund could come to mean 'a basic 10-ness', i.e., in a

decimal system 'a 10-ness of 10s or 100' as opposed to simply '100'. On

this, two observations. First, this same type of semantic connection

between '10' and '100' is mentioned by Szemer?nyi as a reasonable and

a generally accepted hypothesis for earlier Indo-European: ". . . '100'

was not only conceived, but also expressed as 'ten tens' or 'a decad of

decads'. The primitive form was thus * dekmt dekmt?m [the latter con

stituent a gen. pi.] or * (d)kmtmt?m. . . ."24 Second, if one keeps in

mind the phonological changes from Indo-European to Germanic

registered above, then there must have been a stage within early Ger

manic after the ist ss and before the cor c dele change when the

morphemes for '10' and for '100' were close to homophonous: IE

* d?knt '10' and * knt- '100' ?? early Gmc. * t?hund and * h?nd-. Hence

even if the earlier semantic connection between '10' and '100' should

have become obscured, it could in view of this homophony easily have

been reinstated in Germanic times.

In conclusion, the pre-Germanic ordinals listed above and recon

structed on the basis of the axioms listed at the outset seem to evince a

number of advantages over those produced by earlier suggestions,

and few if any of their weaknesses. Pending the discovery of new data

or new principles of reconstruction, the system of cardinal numerals

posited here constitutes the most likely reconstruction for late, pre

Germanic Indo-European and early Proto-Germanic as well.

24 Szemer?nyi, Studies in the Indo-European System of Numbers, pp. 139?40.

This content downloaded from

158.223.122.128 on Sun, 24 Dec 2023 14:28:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Easy Ways to Enlarge Your German VocabularyFrom EverandEasy Ways to Enlarge Your German VocabularyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- Bloomfield, L. A Semasiological Differentiation in Germanic Secondary AblautDocument45 pagesBloomfield, L. A Semasiological Differentiation in Germanic Secondary AblautRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- General Characteristics of The Germanic Languages - MeilletDocument61 pagesGeneral Characteristics of The Germanic Languages - MeilletAdam PaulukaitisNo ratings yet

- Hill - Germanic Weak PreteriteDocument49 pagesHill - Germanic Weak PreteriteXweuis Hekuos KweNo ratings yet

- 6.1. First Sound ShiftDocument8 pages6.1. First Sound ShiftOanaBunNo ratings yet

- Chambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary (part 4 of 4: S-Z and supplements)From EverandChambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary (part 4 of 4: S-Z and supplements)No ratings yet

- Linguistic Society of America Language: This Content Downloaded From 140.206.154.232 On Sat, 10 Jun 2017 05:56:10 UTCDocument5 pagesLinguistic Society of America Language: This Content Downloaded From 140.206.154.232 On Sat, 10 Jun 2017 05:56:10 UTCyugegeNo ratings yet

- Pollock PDFDocument61 pagesPollock PDFzemljoradnikNo ratings yet

- The History of Rome, Book I The Period Anterior to the Abolition of the MonarchyFrom EverandThe History of Rome, Book I The Period Anterior to the Abolition of the MonarchyNo ratings yet

- Key Issues in English EtymologyDocument29 pagesKey Issues in English Etymology莊詠翔No ratings yet

- Calvert Watkins, HITTITE AND INDO-EUROPEAN STUDIES - THE DENOMINATIVE STATIVES IN - ĒDocument43 pagesCalvert Watkins, HITTITE AND INDO-EUROPEAN STUDIES - THE DENOMINATIVE STATIVES IN - ĒBrymhildhr87No ratings yet

- On The Names For Wednesday in Germanic DialectsDocument14 pagesOn The Names For Wednesday in Germanic DialectsTiago CrisitanoNo ratings yet

- Pollock (1989) Movement & IPDocument61 pagesPollock (1989) Movement & IPdjtannaNo ratings yet

- Concise Etymological DictionaryDocument674 pagesConcise Etymological Dictionarysakariaxa97% (35)

- An Introduction To The Rhythmic and Metric of The Classical Languages Schmidt 1883Document216 pagesAn Introduction To The Rhythmic and Metric of The Classical Languages Schmidt 1883explorareamunteluiNo ratings yet

- Laws of Sound ChangeDocument18 pagesLaws of Sound ChangeNabeel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Introductory. General Characteristics of Germanic LanguagesDocument19 pagesIntroductory. General Characteristics of Germanic LanguagesІрина МиськівNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 Proto Germanic Language Grimm Verner LawDocument38 pagesLecture 5 Proto Germanic Language Grimm Verner Lawduchese100% (1)

- Fox ReviewDocument7 pagesFox ReviewHun ChhuntengNo ratings yet

- CHEMISTRY German-English DictionaryDocument344 pagesCHEMISTRY German-English Dictionaryannawajda100% (1)

- Word puzzles reveal linguistic contrastsDocument23 pagesWord puzzles reveal linguistic contrastsKashif NadeemNo ratings yet

- INITIAL CONSONANTS AND SYNTACTIC DOUBLING IN WEST ROMANCEDocument7 pagesINITIAL CONSONANTS AND SYNTACTIC DOUBLING IN WEST ROMANCEyugewansuiNo ratings yet

- Final Paper. 14.11.22Document4 pagesFinal Paper. 14.11.22Людмила ЧиркинянNo ratings yet

- Practical Hebrew Grammar with Exercises and ChrestomathyDocument278 pagesPractical Hebrew Grammar with Exercises and ChrestomathyLeonard Michlin100% (1)

- GUIDE TO INDO-EUROPEAN ROOTSDocument385 pagesGUIDE TO INDO-EUROPEAN ROOTSmhc032105636No ratings yet

- Dialectology and Language ChangeDocument4 pagesDialectology and Language ChangemiftaNo ratings yet

- R.B. Farrell - Dictionary of German Synonyms-Cambridge University Press (1977)Document424 pagesR.B. Farrell - Dictionary of German Synonyms-Cambridge University Press (1977)kostasNo ratings yet

- HIAT Transcription ConventionsDocument7 pagesHIAT Transcription ConventionsDiosa Jimenez (Katrina May)No ratings yet

- Swedish GrammarDocument220 pagesSwedish GrammarAlex WujanowitschNo ratings yet

- Kinder-Und Hausmärchen Der Grebrüder GrimmDocument232 pagesKinder-Und Hausmärchen Der Grebrüder GrimmSalvador Alcantar100% (1)

- German School of Linguists Karl Brugmann, Hermann Osthoff, Hermann Paul, Eduard Sievers, Karl VernerDocument3 pagesGerman School of Linguists Karl Brugmann, Hermann Osthoff, Hermann Paul, Eduard Sievers, Karl VernerВікторія БабичNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1 in LexicologyDocument6 pagesSeminar 1 in LexicologyОльга ВеремчукNo ratings yet

- Goblirsch, Kurt - Gemination, Lenition, and Vowel Lengthening - Arriving at The Goal - Vowel Lengthening PDFDocument36 pagesGoblirsch, Kurt - Gemination, Lenition, and Vowel Lengthening - Arriving at The Goal - Vowel Lengthening PDFdecarvalhothiNo ratings yet

- What If... English Versus German and EnglishDocument2 pagesWhat If... English Versus German and EnglishWen-Ti Liao100% (1)

- Notational Conventions 2Document10 pagesNotational Conventions 2Yol Anda San Roman FiolNo ratings yet

- From Latin to Romance LanguagesDocument41 pagesFrom Latin to Romance LanguagesyugewansuiNo ratings yet

- Yale Onesource Client Service Setup 3 0-7-103!09!2021Document22 pagesYale Onesource Client Service Setup 3 0-7-103!09!2021maryfisher180884rkz100% (61)

- A Middle High German PrimerDocument173 pagesA Middle High German PrimerJohann CoxNo ratings yet

- Gothic Wright1954 o PDFDocument376 pagesGothic Wright1954 o PDFPilar perezNo ratings yet

- ALEXIADOU Perfects Resultatives and Auxiliaries in Early EnglishDocument75 pagesALEXIADOU Perfects Resultatives and Auxiliaries in Early EnglishjmfontanaNo ratings yet

- History of English 3Document9 pagesHistory of English 3VLAD DRAKULANo ratings yet

- German PhoneticsDocument166 pagesGerman PhoneticsFarah100% (1)

- A Concise Etymological Dictionary of The English LanguageDocument688 pagesA Concise Etymological Dictionary of The English LanguagefaceoneoneoneoneNo ratings yet

- The Reviewer Simonetta Di Prima Is A Teacher and Teacher TrainerDocument4 pagesThe Reviewer Simonetta Di Prima Is A Teacher and Teacher TrainerMcayuryNo ratings yet

- Vlhismodling ScriptDocument54 pagesVlhismodling Scriptnimz 203No ratings yet

- Hyster Onesource Client Service Setup 3 0-7-103!09!2021Document22 pagesHyster Onesource Client Service Setup 3 0-7-103!09!2021jakereid160983wam100% (66)

- Abstractness in PhonologyDocument27 pagesAbstractness in PhonologyjagiyaaNo ratings yet

- Beekes The Origins of Indo European Nominal InflectionDocument260 pagesBeekes The Origins of Indo European Nominal InflectionDavid BuyanerNo ratings yet

- GREEK DIALECTS - Gregory NagyDocument212 pagesGREEK DIALECTS - Gregory NagyRobVicentin100% (1)

- English Digraphs HistoryDocument32 pagesEnglish Digraphs HistoryamirzetzNo ratings yet

- HEL Lecture 1-NotatkaDocument4 pagesHEL Lecture 1-NotatkakiniaNo ratings yet

- Common characteristics of the Germanic languagesDocument6 pagesCommon characteristics of the Germanic languagesaniNo ratings yet

- Atwood C.P. - Huns and Xiongnu. New Thoughts On An Old ProblemDocument26 pagesAtwood C.P. - Huns and Xiongnu. New Thoughts On An Old ProblemcenkjNo ratings yet

- A Middle High German Primer, With Grammar, Notes, and Glossary by Joseph WrightDocument236 pagesA Middle High German Primer, With Grammar, Notes, and Glossary by Joseph Wrightkurt_stallingsNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Features of Germanic LanguagesDocument19 pagesLinguistic Features of Germanic LanguagessodaviberNo ratings yet

- High German Consonant ShiftDocument10 pagesHigh German Consonant ShiftJuan Carlos Moreno HenaoNo ratings yet

- Social Network AnalysisDocument641 pagesSocial Network AnalysisSocorro Carneiro100% (3)

- Absorption Two Studies of Human Nature - BronkhorstDocument144 pagesAbsorption Two Studies of Human Nature - BronkhorstlynnvilleNo ratings yet

- Yoga and FetishismDocument21 pagesYoga and FetishismGuillermo SaldanaNo ratings yet

- Eghteen Cent WetwareDocument30 pagesEghteen Cent WetwarePawel OzzkowskiNo ratings yet

- Communication Strategies For Teachers and Their Students in An EFL SettingDocument13 pagesCommunication Strategies For Teachers and Their Students in An EFL SettingRAHMAT ALI PUTRANo ratings yet

- Order of Adjectives PDFDocument1 pageOrder of Adjectives PDFstuart001No ratings yet

- DEMO ENGLISH FinalDocument8 pagesDEMO ENGLISH FinalDanivie JarantaNo ratings yet

- Learn Adverbs of MannerDocument10 pagesLearn Adverbs of Mannerelin_zlinNo ratings yet

- Grammar and Tips When Learning Japanese OnomatopoeiaDocument3 pagesGrammar and Tips When Learning Japanese Onomatopoeiaharuki nakazakiNo ratings yet

- Verb Tense Analysis of Research Article Abstracts in Asian Efl JournalDocument8 pagesVerb Tense Analysis of Research Article Abstracts in Asian Efl Journalallvian susantoNo ratings yet

- Decisions, Decisions: Warm-UpDocument2 pagesDecisions, Decisions: Warm-UpnunoNo ratings yet

- Organization Audience Cannot: Presentation Rubric Poor (2.0) Fair (3.0) Good (4.0) Excellent (5.0)Document2 pagesOrganization Audience Cannot: Presentation Rubric Poor (2.0) Fair (3.0) Good (4.0) Excellent (5.0)MaRiA dAnIeLaNo ratings yet

- Second Language Acquisition: To Think AboutDocument15 pagesSecond Language Acquisition: To Think AboutStephanie ZaraNo ratings yet

- Level-2 InglesDocument55 pagesLevel-2 Inglesashley veloz100% (1)

- Nihongo 1 Course Guide Introduces Basic Japanese CommunicationDocument5 pagesNihongo 1 Course Guide Introduces Basic Japanese Communicationjohnford florida100% (1)

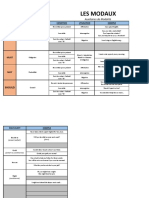

- Les Modaux: Auxiliaires de ModalitéDocument2 pagesLes Modaux: Auxiliaires de ModalitéMaxime MAYNo ratings yet

- Starfish K2 Student - S Book PDFDocument25 pagesStarfish K2 Student - S Book PDFDiego JuarezNo ratings yet

- Afl2601 2020 TL 201 1 BDocument22 pagesAfl2601 2020 TL 201 1 BKeitumetse LegodiNo ratings yet

- Reiza Fitria Indah Avrillia - Task 2 - Paper Writing PDFDocument7 pagesReiza Fitria Indah Avrillia - Task 2 - Paper Writing PDFAngga Aulia RahmanA21No ratings yet

- International English Qualifications: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument12 pagesInternational English Qualifications: Frequently Asked Questionsedmund uginiNo ratings yet

- ELC501 (1) Confirm Meaning of Words Using A Dictionary - ODLDocument20 pagesELC501 (1) Confirm Meaning of Words Using A Dictionary - ODLHamzah AmshahNo ratings yet

- Assessement 1SE Getting ThroughDocument2 pagesAssessement 1SE Getting ThroughIhsane DzNo ratings yet

- Intro To Ling W67 Syntax HandoutDocument8 pagesIntro To Ling W67 Syntax HandoutLinh BảoNo ratings yet

- Eng114 MidtermDocument4 pagesEng114 MidtermAllan Siarot BautistaNo ratings yet

- 11°graders CTG 2Document8 pages11°graders CTG 2Osiris DixonNo ratings yet

- Clause As Message 3.1. Theme and Rheme FRANDocument8 pagesClause As Message 3.1. Theme and Rheme FRANbelen oroNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Resume 2Document4 pagesAnatomy of A Resume 2Anna CruzNo ratings yet

- Readings Module 1Document2 pagesReadings Module 1use diazNo ratings yet

- U1. Metals PDFDocument11 pagesU1. Metals PDFCristi TDNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument9 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayGianna Gayle S. FondevillaNo ratings yet

- EDUC 203 (Assessment in Learning 2) Scoring Rubric Assignment 1 Semester, A.Y. 2021-2022 RESEARCH: Type Your Answers Below The Questions WithDocument1 pageEDUC 203 (Assessment in Learning 2) Scoring Rubric Assignment 1 Semester, A.Y. 2021-2022 RESEARCH: Type Your Answers Below The Questions WithBernaNo ratings yet

- Implied Main Idea ExercisesDocument6 pagesImplied Main Idea ExercisesClaus DionicioNo ratings yet

- Pro-Speaking - Les 10 Pro - SBDocument47 pagesPro-Speaking - Les 10 Pro - SBTuyết TrinhNo ratings yet

- Beginner'S Visual Catalog OF Maya Hieroglyphs: Alexandre TokovinineDocument36 pagesBeginner'S Visual Catalog OF Maya Hieroglyphs: Alexandre TokovinineJersonNo ratings yet