Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stevens Beyer Trice1978

Uploaded by

Robert BagarićOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stevens Beyer Trice1978

Uploaded by

Robert BagarićCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessing Personal, Role, and Organizational Predictors of Managerial Commitment

Author(s): John M. Stevens, Janice M. Beyer and Harrison M. Trice

Source: The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Sep., 1978), pp. 380-396

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/255721 .

Accessed: 16/06/2014 01:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Academy

of Management Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Academy of Management Journal

1978, Vol. 21, No. 3. 380-396.

Assessing Personal Role, and

Organizational Predictors of

Managerial Commitment'

JOHN M. STEVENS

Pennsylvania State University

JANICE M. BEYER

State University of New York at Buffalo

HARRISON M. TRICE

Cornell University

Using a role and exchange theory framework, this

study examines the commitment to their organization and

to the federal service of 634 managers in 71 federal gov-

ernment organizations. Results indicate that certain role

factors such as tenure and work overload and personal

factors such as attitude toward change and job involve-

ment are strong influences on commitment. Implications

of the findings and the need for further theoretical and

methodological refinements are discussed.

Commitment to the organization, profession, and role has received wide

attention in recent organizational behavior literature (Sheldon, 1971;

Buchanan, 1974; Schoenherr & Greeley, 1974; Porter, Steers, Mowday &

Boulian, 1974; Alutto & Hrebiniak, 1975; Steers, 1977). In 1960, Becker

observed that the concept of commitment had enjoyed wide usage with little

John M. Stevens is Assistant Professor, Institute of Public Administration, The Pennsyl-

vania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Janice M. Beyer is Associate Professor, School of Management, State University of New

York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York.

Harrison M. Trice is Professor, New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations,

Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

1 This research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and

Alcoholism to the Cornell Program on Occupational Health and Alcoholism. The first two

authors would also like to acknowledge the support of the School of Management, SUNY

at Buffalo, and the Institute of Public Administration, The Pennsylvania State University.

This article is based on a Ph.D. dissertation prepared at SUNY at Buffalo by the first author,

who would like to thank Joseph A. Alutto and Douglas R. Bunker for their comments. An

earlier version of this paper was presented at the Academy of Management meetings in

Kansas City, August 12, 1976. All of the authors would like to thank those at Cornell who

helped in the data collection and analysis, especially Richard E. Hunt and Cynthia Coppess.

They would also like to thank R. Danforth Ross for his invaluable suggestions on the data

analysis.

380

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 381

formal analysis or concrete theoretical reasoning. He argued that commit-

ment involves "consistentlines of activity" in behavior that are produced by

exchange considerations that he called side-bets; examples of side-bets are

a pension that grows in proportion to years in the organization or man-

agerial prerogatives that are attached to an attained organizational office or

position. Ritzer and Trice (1969) developed an operationalization for the

Becker side-bet concept of commitment and tested aspects of the theory

on both organizational and occupational commitment. This research con-

tinues and extends this line of inquiry by examining commitment to the

organization and to the federal service in a sample of managers working in

71 organizations within the U.S. government.

Definitionsof Commitment

Despite substantial earlier work, Buchanan (1974) concluded that an

acceptable definition of organizational commitment was still lacking. A

more basic problem appears to be that there are at least two distinct ap-

proaches to defining commitment, the psychological approach and the ex-

change approach. In an example of the psychological approach, Sheldon

defines commitment as ". .. an attitude or an orientation toward the

organization which links or attaches the identity of the person to the or-

ganization" (1971, p. 143). Kanter (1968) and Buchanan (1974) also

emphasize the affective attachment of the individual to the organization. A

common deficiency in this approach is that commitment is treated as

discrete from complementary work attitudes without specifying the nature

or direction of links with these other orientations (e.g., loyalty, job in-

volvement, motivation, et cetera).

The exchange approach is exemplified by Becker (1960) and Becker and

Carper (1956), who advanced the notion of "side-bets" as influences that

produce a willingness to remain attached to the object of the commitment.

Becker argued that commitments come into being "when a person, by

making a side-bet, links extraneous interests with a consistent line of

activity" (1960, p. 32). When side-bets are made to an organization (e.g.,

pension plans or other accrued investments), the individual perceives as-

sociated benefits as positive elements in an exchange and, being reluctant to

lose these benefits, is more likely to stay with that organization. The indi-

vidual thus become organizationally committed. If other investments, such

as time or identification, are made to an occupation, the side-bet mechanism

operates to produce occupational commitment. With its economic rationale,

this approach gives us a general model for commitment that can be attached

to various objects and that allows for a variety of possible influences-

both positive and negative.

Neither the psychological or side-bet approaches has developed an inte-

grated consideration of the full range of relevant factors that may determine

the attachment of the individual to the organization or the leaving or stay-

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

382 Academy of ManagementJournal September

ing behavior of organizational members. Both a clarification of the de-

finitional disagreements and a theoretical framework are badly needed.

TheoreticalFramework

The purpose of this research was to explain commitment as the result of

multiple forces including both psychological and structural (exchange)

determinants, thus working toward an integration of the two approaches

outlined above. A theoretical model that captures the complexity of the

organizational setting and includes individual factors has been advanced

by Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek and Rosenthal (1964) and Katz and

Kahn (1966). They argue persuasively that the context of role-taking is

important for understanding how multiple factors influence organiza-

tional behavior (Katz and Kahn, 1966, p. 186). They also state that role

expectations are determined by the technology of the organization, its

policies, structure, and set of rewards and penalties. Within this model of

role-taking, a manager may use perceived benefits and costs in an exchange

paradigm to evaluate multiple influences that structure his decisions about

ongoing activities (March & Simon, 1958; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959; Hom-

ans, 1961;Blau, 1964, 1974; Jacobs, 1971).

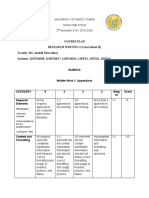

Figure 1 presents the role-taking and exchange framework that will be

tested in this research. Given the complexity of managerial role contexts,

the model incorporates personal, role-related, and organizational variables.

This is the first attempt, of which the authors are aware, to look at these

three types of determinants of organizational commitment simultaneously.

This model also provides for the integration of the two approaches discussed

FIGURE 1

Role TakingModelof CommitmentProcess

Personal Focal Manager

Attributes E E '

At>triut Ex E Propensityto Stay

Role-Related Perceived Ihac a1 Role

Wtor With or Leave

Factors Role Behavioror rganization or

'g t I Attitude Federal Service

Organiz e '- IAttitude

Organizational 0

Factors -"" n

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 383

earlier. To illustrate, in earlier career phases, managerial commitment may

be influenced more by psychological or personal factors than by side-bets,

since there has been little time for them to accrue. But with increasing

tenure, personal factors may recede in importance and the side-bet or cost-

benefit factors may "lock-in" certain fixed elements in the exchange equa-

tion, making it more costly to leave and thereby insuring a certain "type"

of commitment. Such managers are committed to the organization; they

may stay with it, but shift or orient their energies to interests outside the

organization or federal service (cf., Dubin, Champoux & Porter, 1975).

They are economically committed but not psychologically committed.

Any factor that accrues positive economic side-bets, such as organiza-

tional tenure, should increase commitment, unless outweighed by con-

comitant negative factors, such as lack of promotion or authority. Thus,

fixed factors (e.g., education, sex, job involvement) or positive dimensions

of the task (such as high managerial level or advanced technology) may

tend to promote commitment, while less fixed but negative factors (such

as too much time in one position and demands of work overload) promote

leaving attitudes. One relatively permanent characteristic that could tend

to lessen commitment is a propensity by the manager to favor change

per se. The relative influence of these factors may depend to a great extent

upon the manager's perceptions of his role and his assessments of what

constitute costs or benefits given competing influences. The fixed factors

may represent a personal, systemic equilibrium that represents commit-

ment, which may have to be disturbed by dynamic factors in order to pro-

duce external search or quitting behavior.

Dependent Variables

There are several reasons for using both organizational and federal

service commitment to explore managerial commitment in this study. First,

research has suggested that occupational and organizational commitment

or identifications are compatible (Ritzer & Trice, 1969; Rotondi, 1975)

and/or complementary (Ritzer & Trice, 1969; Hrebiniak & Alutto, 1972).

Second, federal service commitment shares some characteristics of occupa-

tional commitment: transferability across organizations, socially mandated

set of expectations (Hughes, 1958), and ".. . relatively continuous patterns

of activities" (Form, 1968). Third, as Ritzer and Trice (1969) suggest,

it is possible that members may be tied to organizations through their

commitment to an occupation, since the organization provides the op-

portunity to pursue the occupation. In this sample of federal managers, who

largely occupy positions that do not have an occupational identity outside

of government service, commitment may well be generated initially to a

position or role, which then generates commitment to the employing

organization because the manager cannot occupy that position or role in

other employment sectors. Finally, the federal service is the entity which

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

384 Academy of Management Journal September

provides many of the economically based side-bets described by Becker,

especially job security, pensions, et cetera.

IndependentVariables

The personal or individual variables to be examined in this study are age,

educational level, sex, job involvement, and attitude toward change. Several

studies of commitment have used the age, education, and sex variables

(Ritzer & Trice, 1969; Alutto, Hrebiniak, & Alonso, 1973), but disparate

findings have emerged. Some ambiguity also exists with regard to job

involvement, used as a correlate of a behavioral measure of commitment

(Weiner & Gechman, 1975) or as a component (Buchanan, 1974). No

published research on commitment has investigated the influence of attitude

toward change (Hage & Dewar, 1973) as a predictor of commitment.

The general arguments for using such variables to predict commitment

can be derived from both role and exchange theory. For instance, Becker's

side-bet theory suggests that advancing age, being female, certain role

characteristics, and longer tenure increase an individual's investment in the

federal service or employing organization and therefore the costs associated

with leaving.

Job involvement, as operationalized and used in this research, concerns

an individual's ego involvement with the job, i.e.,,the degree to which his

self-esteem is affected by his work performance (Lodahl &Kejner, 1965). It

follows that individuals very involved in their job will also have substantial

side-bet investments in federal service and employing organizations, which

provide the opportunity for them to act out "internalized values about the

goodness of work" (Lodahl & Kejner, 1965, p. 24).

It is also logical to assume that an individual who is favorably disposed

toward change would incur less personal costs in leaving an organization as

a response to increasing pressures. If role conflict or overload increased, the

change-orientedmanager'sexchange equation would permit easier exit from

the situation. Positive attitudes toward change should thus be negatively

related to commitment.

Recent research indicates that role-related factors are important influ-

ences on commitment (Alutto & Hrebiniak, 1975; Steers, 1977), involve-

ment (Patchen, 1970), organizational identification (Lee, 1971), or-

ganizational socialization (Buchanan, 1974), and organizational attraction

(Dubin et al., 1975). The role-related variables to be used in this study

are: work overload, managerial level, organizational tenure, positional

tenure, task characteristics, and perceptions concerning the importance

for promotion of performance, seniority, and technical skills. Role variables

include more dynamic aspects of the job situation that may make staying

with a given organization or the federal service more or less attractive at a

given point in time: Work overload would be perceived as a cost and

negatively affect commitment. Too much time in any one position may be

perceived as career stagnation and have an adverse effect on commitment,

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 385

whereas length of time in an organization would mean increased side-bets

and lead to increased commitment.

Katz and Kahn (1966) and Kahn et al. (1964) contend that the division

of labor in organizations provides the major stable elements of roles and

directly influences the reward system. If the manager's task requires ad-

vanced skills, his importance to the organization is greater, which is

likely to increase his/her benefits, resulting in higher commitment. When

performance-andtechnical skills for promotion are more important, greater

commitment is expected because achievement-oriented, universalistic stan-

dards are consonant with the bureaucratizationexpected in public organiza-

tions. If seniority were perceived to be very important for career advance-

ment, the emphasis on achievement would be diluted, and commitment

would be weakened.

The organizational variables to be used are size (total number of full-

time employees), centralization (concentration of decision-making in-

fluence at top managerial levels), percent of supervision (total number of

supervisors divided by total number of employees), and presence of a

union.

Intuitively, size may appear to be a negative influence on commitment.

However, a large organization may require greater investments from the

manager in terms of coordination, control, and innovative behavior (Bald-

ridge & Burnham, 1975), or produce larger groups of peers and additional

opportunity for interpersonal interaction (Rice & Mitchell, 1973) which

would increase commitment. In addition, the concept of "empirebuliding" is

not unknown in governmental organizations, and a large organization may

increase chances for promotion or role enlargement that could enhance the

position of the officeholder.

As a measure of participation in decision making, more centralization

would mean that power resides in a few hands and lessens the individual

manager's autonomy and prerogatives in decision making. This condition

would probably be perceived as a cost and result in low levels of commit-

ment.

Ivancevich and Donnelly (1975) found a positive relationship between

span of control and attitudes such as self-actualization and anxiety-stress

in their study of salesmen. This suggests that commitment may also be

positively related to span of control. However, Ouchi and Dowling (1974)

pointed out that smaller spans of control permit greater closeness of con-

tact between a superior and his subordinates; thus larger spans of control

could conceivably have negative effects on commitment, suggesting an

inverse relationship. Recognizing the uncertainty, a positive relationship

will be hypothesized.

Past studies suggest that public sector unions decrease decision making

autonomy (Stanley & Cooper, 1972; Kochan, 1975; Kochan, Huber &

Cummings, 1975) and create conflict because of different goals and con-

stituencies than management. Thus, the presence of a union may detract

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

386 Academy of ManagementJournal September

TABLE 1

Basic Statistics for Independent and Dependent Variables

Hypothesized

Relationship

with

Variable Mean sd Cases Commitmenta

Personal Attributes

1. Sex of supervisor .162 .369 620 +

2. Age of supervisor 3.069 1.019 623 +

3. Change attitude 4.354 .852 625

4. Job involvement 2.545 .399 627

5. Education in years 15.314 2.369 611

Role-Related

6. Manageriallevel 4.740 1.017 632 +

7. Work overload 2.140 .790 616

8. Years in organization 10.504 8.636 614 +

9. Years on position 4.573 4.672 612

10. Skill level of subordinates 3.609 1.326 614 +

11. Performance in promotion .008 .768 612 +

12. Technical skill in promotion .000 .999 613 +

13. Seniority in promotion .000 1.000 612

OrganizationalFactors

14. Organizationalsize 338.082 298.565 634 +

15. Union presence .821 .383 632

16. Percent of supervisionb 14.470 5.429 634 +

17. Centralizationof authority 1.189 4.440 634

Commitment

18. Organizational commitment 3.618 .937 608

19. Federal Service commitment 4.143 .922 610

a A + indicates a positive and a - indicates a negative relationship with both forms

of managerialcommitment.

b A measure of average span of control.

from decision making autonomy, create costs for the manager, drain re-

sources, and decrease commitment.

Independent and dependent variables, basic descriptive statistics, and the

direction of hypothesized relationships are presented in Table 1.

DATA AND METHODS

Sample and Data Collection

Data were collected by the Cornell Program on Occupational Health

and Alcoholism between April and September of 1974 from 634 super-

visors in 71 federal government installations in the Departments of Health,

Education and Welfare; Transportation; Justice; Agriculture; Commerce;

Housing and Urban Development; Interior; Treasury; and General Services

Administration. A random sample of installations located in the Boston,

New York, and Philadelphia civil service administrationregions was drawn,

using department, region, and organizational size as stratifying variables.

Within each installation, a systematic random sample of supervisors was

interviewed, with the size of that sample inversely proportional to the size

of the installation.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 387

Five research instruments were devised, pretested, refined, and eventu-

ally administered within the sample installations. The data presented here

were taken from an instrument that collected structural data on the in-

stallation and from the supervisor instrument, which consisted primarily

of closed-ended questions with response formats in the form of yes-no,

Likert scales, semantic differentials, et cetera. Supervisory data were col-

lected in private face-to-face situations by interviewers trained specifically

for this project. Only one sample installation refused to cooperate with the

study and was replaced, and only six individual supervisors refused

cooperation.

Statisticsand Measurement

The principal method of data analysis used in this study is multiple

regression because of the multivariate relationships specified in the re-

search model. The primary strategies used to construct scales from multiple

item measures were factor analysis and standardization of measures [see

Stevens (1976) for further details].

To measure commitment, managers were asked if they would leave the

installation or the federal service given no, slight, or large increases in pay,

freedom, status, responsibility, and opportunity to get ahead. They re-

sponded by checking one of three categories: would definitely leave, un-

decided, or would definitely not leave. The object in constructing a scale

from such items was that respondents who would stay with certain induce-

ments were more committed than those who would leave with the same or

less inducements.

Because of controversy in the literature, two scales were used: The

Ritzer and Trice (1969) (R-T) scale composed of the five inducement

items (replicating their original scaling procedures) and the "slight change"

only items, favored by Hrebiniak and Alutto (1972).2

The operationalizations of most independent variables were based on the

responses of supervisors. Variables 3, 4, 7, 11, 12, and 13 (Table 1) were

multiple-item scales based on factor analytic results. Centralization was

based on a decision matrix approach to measuring influence in decision

making (Beyer & Lodahl, 1976). Further details on the operationalization

of these variables are available from the authors.

RESULTS

The intercorrelation matrix of all of the variables to be used in subse-

quent analyses is given in Table 2. In these results, seven of the 17 hypoth-

2 The

operationalizations,scale construction, and tests of reliability and validity for the

independent and dependent variables are discussed in detail in Stevens (1976). In addition,

questions regarding the appropriatenessof measures used by Alutto et al. (1973) to assess

the R-T scaling procedures are discussed in Beyer, Stevens, and Trice (1977).

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

388 Academy of Management Journal September

TABLE

Correlation a Matrix for

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Sex

2. Age -.061

3. Change .098 .027

4. Job involvement -.047 .177 .130

5. Education -.206 -.179 .004 .117

6. Managerlevel -.148 -.007 -.094 .108 .255

7. Overload -.008 -.093 .113 -.012 .118 -.082

8. Years/organization .040 .442 .008 .044 -.198 -.112 -.022

9. Years/position -.083 .377 -.015 .018 -.103 -.058 -.032

10. Skill level -.164 -.078 -.049 .020 .454 .184 .033

11. Promotion/performance .020 -.014 .043 .054 -.090 .049 -.155

12. Promotion/technical -.025 .113 -.009 .043 -.109 -.060 -.055

13. Promotion/seniority .020 .160 .048 .122 -.145 -.109 .042

14. Organization size .072 .025 .037 .004 -.035 -.286 -.015

15. Unions .051 .044 .061 .031 -.053 -.124 .062

16. Percent of supervision --.117 .059 -.030 .026 .074 .018 .001

17. Centralization -.025 -.011 .036 .026 .044 .184 .019

18. Organizationcommitment .006 .117 -.074 .159 .045 .061 -.163

19. Federal commitment .062 .107 -.081 .042 -.204 -.037 -.250

a With 600 df, when r = .08, p = .05; r = .11, p = .01; r = .14, p = .001.

esized relations between independent variables and organizational com-

mitment are statistically significant; eight are significant for federal service

commitment. The two measures of commitment are correlated substantially

(r = .40) but exhibit sufficient independence to support the notion of

separate constructs and measures. Furthermore, two of the significant

correlates (job involvement and education) are clearly different across

measures, and another (skill level) produces relationships in opposite

directions.

As predicted, age, organizational tenure, and the importance of per-

formance and technical skills in promotion are positively related to both

types of commitment, while work overload is negatively related. In addition,

job involvement and skill level are positively related to organizational com-

mitment. The additional correlates of federal service commitment all show

negative relations: a positive attitude toward change, education, and skill

level. All but the last-cited relationship are in the hypothesized direction.

While these results largely support the hypotheses, they do not assess the

unique contribution of each of the variables.

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple regression analyses of the

two alternative measures of commitment on the personal (P), role (R),

and organizational (0) predictor variables. All of the independent variables

were entered into each regression equation. For brevity, only statistically

significant results are presented; however, if an independent variable was

found to be significantfor either of the two commitment scales, both results

for the variable are presented for comparability.

The regression results in Table 3a suggest very similar degrees of explan-

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 389

2

Commitment Study Variables

8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

.446

-.104 -.083

-.045 -.039 -.039

.073 .042 -.022 .483

.055 .030 -.162 .052 .233

.204 -.019 -.022 .045 -.064 -.108

.114 .072 -.108 .124 .060 .031 .233

-.106 -.003 .158 -.098 .074 .071 -.395 -.262

.018 .020 -.021 .008 .031 .116 -.160 -.058 .116

.184 -.009 .104 .090 .087 -.014 .029 .032 -.032 -.023

.129 -.037 -.096 .172 .134 .012 .044 .078 -.065 -.014 .404

atory power for the two measures of organizational commitment. Four of

the variables significantly related to commitment are the same across both

measures.

Table 3b presents the results for federal service commitment. The explan-

atory power of the R-T measure is greater than for the "slight" measure.

Also, based upon the construct validation analysis in the scale construction

phase, reliability tests, the scale homogeneity criterion, and the advantages

of comparability with past studies and across types of commitment, the

Ritzer-Trice (R-T) scale was chosen as the central measure for both ele-

ments of managerial commitment. It is those results that will be discussed

unless otherwise noted.

Influenceson Commitment

In Table 3a, five role and personal variables are significant and another

personal variable is a marginally significant predictor of organizational

commitment, as measured by the R-T scale. Years in the organization

emerge as the best positive predictor and work overload as the largest

negative predictor, giving support to the exchange or side-bet approach to

commitment. Job involvement is also a strong positive predictor, underlining

the importance of psychological predispositions toward work. The findings

here generally support the hypotheses and usefulness of the composite

research model. In addition, the positive influence of skill level of sub-

ordinates suggests that job content can also be an important influence on

organizational commitment.

The finding that positional tenure is negatively related to organizational

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

390 Academy of ManagementJournal September

TABLE 3

Regression Results for Alternative Measures of Managerial Commitment

on Personal, Role, and Organizational Variables

A. OrganizationalCommitment(n = 611)

StandardizedCoefficients

CommitmentMeasures Evaluated

Var.

Influence Cat. R-T Scale Slight

Work overload R -.15**** -.13***

Years in the organization R .24********

Job involvement P .15** 3***

Skill level of subordinates R .11* .14**

Positive change attitude P -.08* .01

Years in current position R -.12*** -.12***

Manager'sage P .04 .09*

R2 .13 .13

B. Federal Service Commitment(n = 610)

StandardizedCoefficients

CommitmentMeasures Evaluated

Var.

Influence Cat. R-T Scale Slight

Work overload R -.21**** .20****

Years in the organization R .13*** .06

Positive change attitude P -.08 -.03

Years in current position R -14*** -.15**

Level of education P -.14* -.10*

Importanceof performance

for promotion R .10** .07

R2 .15 .10

*p < .10

** p < .05

*** p < .01

**** p < .001

commitment refines the side-bet concept by indicating that as positive side-

bets or benefits accrue with longevity, negative perceptions or costs of

career stagnation may concurrently develop. An exchange framework may

thus be necessary to explain the relative increments and decrements in the

managerial role associated with varying levels of commitment.

As predicted, the findings also indicate that if a manager has a positive

attitude toward change, he is likely to be less committed to the organization.

Probably a manager who values change positively would be more disposed

to perceive a change in employers or organizations as an acceptable re-

sponse to increased costs of participation than a manager who dislikes the

idea of change.

The age of the manager was not significantly related to organizational

commitment in the multivariate analyses although they were significantly

correlated (r= .12). Taken together, these results suggest that the expected

side-bet relation between age and commitment found in other studies may

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 391

be spurious. Alternatively, moderating variables may affect the influence

that age has on commitment.

The significant results for federal service commitment (Table 3b) are

also in the hypothesized direction; however, certain propositions involving

the psychological and organizational factors for federal service commitment

are clearly not supported. Findings for education completed support the

hypotheses indicating that educational level negatively influences commit-

ment to the federal service. This result is understandablein terms of a link-

age between education and improved external alternatives, and also because

assimilation into professional value sets via education would lead to outside

identifications-in this case, outside the federal service. Additionally, it is

possible that the federal manager perceives the opportunity to use his educa-

tion to be better outside the federal service.

The perceived importance of performance criteria for promotion, which

include unit performance, quality of managerial performance, interpersonal

skills, and skills in applying formal policies, enters as a significant predictor

of federal service commitment but not of organizational commitment. This

result could mean that for the federal service, overall performance is

perceived as important for career advancement, but that within the or-

ganization, more immediate influences such as dimensions of task or in-

terpersonal considerations override performance considerations. This find-

ing is interesting for this managerial population because the conventional

wisdom may suggest that seniority would instead be an important in-

fluence on commitment of federal workers, but the belief that this criterion

is importantfor promotion was unrelated to either type of commitment. Nor

was technical skill found to be either a positive or negative influence on

organizational or federal service commitment in the regression results. The

findings suggest that managers who believe in the merit system are some-

what more committed to the federal service, but that technical expertise is

perhaps not seen as consistently rewarded in the merit system.

DISCUSSION

Overall in this study, role-related factors are more important predictors

of organizational and federal service commitment than other variables, even

though certain personal variables emerged as significant. It is possible that

other personal or organizational variables may be more important predictors

of commitment, but some of these (i.e., job satisfaction) would yield

results that are not likely to be surprising or hold much explanatory power.

Overall, of course, the amount of variance explained is very modest. Per-

haps this is because of the number of organizations used and the hetero-

geneity of organizational goals and tasks represented in the sample. If this

is the case, great caution must be used in generalizing from studies of single

organizations or homogeneous samples of managerial types beyond the

population sampled.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

392 Academy of ManagementJournal September

The results of both regression analyses indicate that factors with benefit

and cost implications are the most powerful influences on managerial com-

mitment. While some personal variables, such as job involvement and

change attitude, were important, other personal characteristics were not.

Unlike a previous study (Hrebiniak & Alutto, 1972), sex did not emerge as

a significantpredictor. The relationship may have been due to concentration

of one sex in the sample. In the earlier study, the sample consisted primarily

of female teachers and nurses; in this sample, only 16 percent of the federal

managers were females. Another possible interpretation is that sex differ-

ences may be less salient for commitment for the managerial as opposed to

the nonmanagerial employees, implying that female managers assess cost-

benefit exchanges similar to males. Samples with more equal concentrations

of males and females may be needed to adequately test this issue.

The major discrepancies between the hypotheses and findings were for

the organizational variables in the model. Organizational size, centraliza-

tion, and percent of supervision, were not found to be important influences

on managerial commitment. Though no direct relationshipswere found, it is

reasonable to suppose that the influence of organizational factors may be

moderated by role-related variables such as work overload.

Another consistent finding was that a positive attitude toward change was

a negative influence on both organizational and federal service commitment.

This finding may indicate that the value placed upon change as a strategy for

adaptation to societal or organizational expectations may be an important

variable in predicting job changes. It is likely that change values affect per-

sonal cost-benefit ratios by decreasing the psychological costs of leaving a

particular role, job, organization, et cetera and increasing the benefits of

leaving. It is also conceivable that the salience of certain perceived benefits

or costs varies with the manager's predisposition toward change. For

example, managers who tend to favor change or innovation may not be

committed to occupations or organizations where inflexibility or overt

formalization prevails. Other managers may self-select themselves for more

formalized organizations and away from roles calling for innovation.

Although traditionally considered a predictor of commitment, age was

not significantly related to either type of commitment in multivariate anal-

yses and only weakly (r = .12 and .11) in zero-order correlations. Other

variables may moderate the effects of age, especially job involvement (r -

.18 with age, p < .01) and educational level (r = -.18 with age, p < .01).

Work overload is the most significantnegative influence on organizational

and federal service commitment. Federal managers who perceive them-

selves as having too little authority to fulfill their responsibilities, bothered

by work overload, and having to finish the work of others have low

commitment. This finding is actually ratherencouraging, because it involves

a variable that is easier to change then some others. Management can

conceivably alter structural or other factors causing overload before its

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 393

effects cause negative on-the-job performance, leaving, or other personnel

problems.

In general, the results of the study indicate that managerial commitment

has multiple positive and negative determinants. Neither side-bet nor

psychological approaches alone explained the overall results; however, both

can be incorporated into a role-exchange model to examine the various

influences as either benefits or costs. For example, tenure can be a double-

edged factor. It may connote stability and accrued investments; however, it

may also point to decreased opportunity elsewhere and reduced mobility

within the organization itself. Though organizational factors may enter

the benefits/costs considerations of the exchange model through moderat-

ing role factors, the importance of personal factors and task dimensions

generally indicates that commitment to the organization centers on issues

of organizational participation. For both facets of commitment, con-

sistent negative influences such as change values and work overload

deserve further exploration because of the potential for important and

long-term administrative payoffs.

SystemConsiderations

In addition to the variables examined here, other factors may influence

commitment. The level of the multiple correlations obtained suggests that

some important variables may have been omitted in this research: in-

terpersonal influences emanating from peers or organizational socialization

processes may influence commitment to the organization or federal service

through commitment to the immediate work group or organizational unit.

Current conditions in the job market and economy can be expected to

affect costs of leaving or staying.

Also, commitment may be composed of multiple elements, some of

which may be causally or temporally antecedent to others (Stevens, 1976).

Other results suggest that a theoretical framework for ordering the pre-

cedence of various forms of commitment may be a valuable approach to

building a comprehensive theory of commitment.3 Such a theory would

ideally specify the relationships between elements or forms of commitment

and their determinants. A review of the relevant literature exposed both

overlap and ambiguity with regard to competing concepts of commitment.

Terms such as professional commitment, occupational commitment, or-

ganizational loyalty, organizational attraction, organizational identification,

organizational involvement, role commitment, job involvement, or job com-

mitment have been used interchangeably or with no clear differentiation

with regard to related constructs. These concepts could theoretically sub-

sume or complement the elements of commitment studied here or the

3 Earlier versions of this paper

(Stevens, 1976; Stevens, Beyer, & Trice, 1976) employed

path analysis for this purpose. Reviewers questioned the appropriatenessof this technique

because of its assumption of weak causal order and its nonrecursive properties. Readers

interested in these results may write to the first author for copies of the earlier

paper.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

394 Academy of Management Journal September

many related constructs found in the literature. A broader theoretical

framework for delineating precise standardized meanings and for the

examination of possible interrelationships among such concepts in varied

populations could form the basis for explaining and predicting an important

part of behavior in organizations.

Furthermore, it is possible that variables identified here or elsewhere

as predictors of commitment may interact, producing more complicated

effects than have been detected thus far. An empirical examination of such

interactions would seem to require additional theoretical development of

the central concept of commitment as a basis for the development of hy-

potheses about the nature of such interactions. Without such conceptual

guidelines, the search for interactions could produce a maze of confusing,

uninterpretable results. Such an investigation is beyond the scope of this

paper.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this study show that both role and exchange theory are

useful in explaining commitment. The findings suggest that commitment

is a complex facet of organizational behavior that is only partially explained

by existing theories. A system-oriented model that captures additional

open-system factors such as socialization, interpersonal factors, the na-

tional economic situation, the existence of feasible alternatives for the

individual, and the interrelationships of these factors is needed. Ideally,

additional research should also relate commitment attitudes to job search

and leaving behaviors.

Some of the critical issues and questions remaining for students of

organizational behavior are: What are the various components of com-

mitment that overlap, supersede, subsume, or complement organizational

or occupational commitment? How can they be adequately measured and

compared? What are valid behavioral or attitudinal indicators of these

different types of commitment? What are the relevant kinds of commitment

(e.g., to organization, to occupation, to work-groups,to industry, et cetera)?

What are the organizational outcomes associated with different kinds of

commitment? What are the potential benefits of different methodological

approaches, such as path analysis or other causal analysis, to exploring

commitment and to explaining this potentially critical facet of organiza-

tional behavior? How are feasible alternatives to commitment such as

personal or nonorganizational central life interest specified within an

overall theoretical framework?

The regression and correlation analyses presented in this study partially

answer some of the questions by testing a model based on role and ex-

change theory. However, the need for additional work on pertinent con-

cepts, theoretical exploration, and explication of system factors is evident.

Thus far, findings from research on commitment have not been cumula-

tive or conceptually linked into a coherent framework that can be applied

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1978 Stevens, Beyer and Trice 395

to managerial practice within organizations. More conceptual work on a

general theory of commitment is needed to provide guidance for future

empirical studies on the many facets of the concept.

REFERENCES

1. Alutto, J. A., and L. G. Hrebiniak. "Researchon Commitment to Employing Organiza-

tion: Preliminary Findings on a Study of Managers Graduating from Engineering and

MBA Programs" (Paper presented at the Thirty-fifth Annual Meeting, Academy of

Management,New Orleans, 1975).

2. Alutto, J. A., L. G. Hrebiniak, and R. C. Alonso. "On Operationalizingthe Concept of

Commitment,"Social Forces, Vol. 51 (1973), 448-454.

3. Baldridge, J. V., and R. A. Burnham. "OrganizationalInnovation: Individual, Organi-

zational and Environmental Impacts," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 20 (1975),

165-176.

4. Becker, H. S. "Notes on the Concept of Commitment,"American Journal of Sociology,

Vol. 66 (1960), 32-40.

5. Becker, H. S., and J. Carper. "The Elements of Identification with an Occupation,"

American Sociological Review, Vol. 21 (1956), 341-347.

6. Beyer, J. M., and T. M. Lodahl. "A Comparative Study of Patterns of Influence in

United States and English Universities," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 21

(1976), 104-129.

7. Beyer, J. M., J. M. Stevens, and H. M. Trice. "On the AppropriateApplication of Tests

of Reliability: a Research Note on MeasuringCommitment" (Mimeo paper, School of

Management,State University of New York at Buffalo, 1977).

8. Blau, P. M. Exchange and Power in Social Life (New York: Wiley, 1964).

9. Blau, P. M. On the Nature of Organizations (New York: Wiley, 1974).

10. Buchanan, B., II. "BuildingOrganizationalCommitment:The Socialization of Managers

in Work Organizations," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 19 (1974), 533-546.

11. Dubin, R., J. E. Champoux, and L. W. Porter. "CentralLife Interests and Organizational

Commitment of Blue-Collar and Clerical Workers," Administrative Science Quarterly,

Vol. 20 (1975), 411-421.

12. Form, W. H. "Occupationsand Careers," in D. L. Sills (Ed.), International Encyclo-

pedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 11 (New York: MacMillan and the Free Press, 1968),

pp. 245-254.

13. Hage, J., and R. Dewar. "Elite Values Versus OrganizationalStructurein Predicting In-

novation," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 18 (1973), 279-290.

14. Homans, G. C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms (New York: Harcourt Brace

World, 1961).

15. Hrebiniak, L. G., and J. A. Alutto. "Personal and Role-Related Factors in the Devel-

opment of Organizational Commitment," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 18

(1972), 555-573.

16. Hughes, E. Men and Their Work(Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1958).

17. Ivancevich, J. M., and J. H. Donnelly, Jr. "Relation of OrganizationalStructureto Job

Satisfaction, Anxiety-Stress, and Performance," Administrative Science Quarterly,

Vol. 20 (1975), 272-280.

18. Jacobs, T. 0. Leadership and Exchange in Formal Organizations (Alexandria, Va.:

Human Resources Research Organization (1971).

19. Kahn, R. L., D. M. Wolfe, R. P. Quinn, J. D. Snoek, and R. A. Rosenthal. Organiza-

tional Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity (New York: Wiley, 1964).

20. Kanter, R. M. "Commitmentand Social Organization:A Study of Commitment Mech-

anisms in Utopian Communities," American Sociological Review, Vol. 33 (1968),

499-517.

21. Katz, D., and R. L. Kahn. The Social Psychology of Organizations (New York: Wiley,

1966).

22. Kochan, T. A. "Determinantsof the Power of Boundary Units in an Interorganizational

Bargaining Relation," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 20 (1975), 434-452.

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

396 Academy of Management Journal September

23. Kochan, T. A., G. P. Huber, and L. L. Cummings. "Determinantsof Intraorganizational

Conflict in Collective Bargaining in the Public Sector," Administrative Science Quar-

terly, Vol. 20 (1975), 10-23.

24. Lee, S. M. "An Empirical Analysis of OrganizationalIdentification,"Academy of Man-

agement Journal, Vol. 14 (1971), 213-226.

25. Lodahl, T. W., and M. Kejner. "The Definition and Measurementof Job Involvement,"

Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 49 (1965), 24-33.

26. March, J., and H. Simon. Organizations(New York: Wiley, 1958).

27. Ouchi, W. G., and J. B. Dowling. "Defining the Span of Control," Administrative

Science Quarterly, Vol. 19 (1974), 356-365.

28. Patchen, M. Participation, Achievement and Involvement on the Job (Englewood Cliffs,

N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970).

29. Porter, L. W., R. M. Steers, R. T. Mowday, and P. V. Boulian. "OrganizationalCommit-

ment, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Among Psychiatric Technicians," Journal of

Applied Psychology, Vol. 59 (1974), 603-609.

30. Rice, L. E., and T. R. Mitchell. "StructuralDeterminants of Individual Behavior in

Organizations," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 18 (1973), 56-70.

31. Ritzer, G., and H. M. Trice. "An Empirical Study of Howard Becker's Side-Bet

Theory," Social Forces, Vol. 47 (1969), 475-479.

32. Rotondi, T., Jr. "OrganizationalIdentification and Group Involvement," Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 18 (1975), 892-896.

33. Schoenherr, R., and A. Greeley. "Role Commitment Processes and the American

Catholic Priesthood," American Sociological Review, Vol. 39 (1974), 407-426.

34. Sheldon, M. E. "Investmentsand Involvements as Mechanisms Producing Commitment

to the Organization," Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 16 (1971), 143-150.

35. Stanley, D. T., and C. Cooper. Managing Local Government Under Union Pressure

(Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1972).

36. Steers, R. M. "Antecedentsand Outcomes of OrganizationalCommitment,"Administra-

tive Science Quarterly, Vol. 22 (1977), 46-56.

37. Stevens, J. M. Managerial Commitment, Policy Receptivity, and Policy Implementation

in Public Sector Organizations(Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at

Buffalo, 1976).

38. Stevens, J. M., J. M. Beyer, and H. M. Trice. "Personal, Role and Organizational

Predictors of Managerial Commitment" (Mimeo paper, Institute of Public Administra-

tion, Pennsylvania State University, 1977).

39. Thibaut, J., and H. Kelley. The Social Psychology of Groups (New York: Wiley, 1959).

40. Weiner, Y., and A. S. Gechman. "Commitment: A Behavioral Approach to Job In-

volvement" (Paper presented at the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the Academy of

Management,New Orleans, 1975).

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.162 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 01:45:00 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Wiener Commitment in Organizations A Normative ViewDocument12 pagesWiener Commitment in Organizations A Normative ViewAlexandra ENo ratings yet

- Allen e Meyer 1990 - The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and NormativeDocument18 pagesAllen e Meyer 1990 - The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and NormativeThiago Matanza100% (1)

- Allen, Meyer - 1990 - The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment To The OrganizationDocument18 pagesAllen, Meyer - 1990 - The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment To The OrganizationVerySonyIndraSurotoNo ratings yet

- A Very Good ArticleDocument8 pagesA Very Good ArticleridaNo ratings yet

- Allen 1990 MMDocument18 pagesAllen 1990 MMLászló KovácsNo ratings yet

- Jain University Bharathraj Shetty A K (Phdaug2011-93)Document55 pagesJain University Bharathraj Shetty A K (Phdaug2011-93)পার্থপ্রতীমদওNo ratings yet

- Incentive Systems: A Theory of OrganizationsDocument39 pagesIncentive Systems: A Theory of OrganizationsNikolina B.No ratings yet

- 10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsDocument4 pages10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsLe Thi Mai ChiNo ratings yet

- Wong 2002Document20 pagesWong 2002Muhammad Farrukh RanaNo ratings yet

- Whetten Et Al. (2009) Theory Borrowing in Organizational StudiesDocument27 pagesWhetten Et Al. (2009) Theory Borrowing in Organizational StudiesWaqas Ak SalarNo ratings yet

- A Construct Validity Study of The Survey of Perceived Organizational SupportDocument7 pagesA Construct Validity Study of The Survey of Perceived Organizational SupportDrKomal KhalidNo ratings yet

- The Measurement and Antecedents Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment To The OrganizationDocument18 pagesThe Measurement and Antecedents Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment To The OrganizationHajra MakhdoomNo ratings yet

- Organizational Structure and PerformanceDocument17 pagesOrganizational Structure and PerformanceKavita Krishna MoortiNo ratings yet

- Wayne 1997Document31 pagesWayne 1997agusSanz13No ratings yet

- American Sociological AssociationDocument8 pagesAmerican Sociological AssociationFarhana ArshadNo ratings yet

- Moorman 1998Document8 pagesMoorman 1998ana.mariaNo ratings yet

- Differentiation and Integration in Complex OrganizationsDocument49 pagesDifferentiation and Integration in Complex OrganizationsEllaNatividadNo ratings yet

- Organizational Commitment Scale - NepalDocument18 pagesOrganizational Commitment Scale - Nepalhzaneta100% (1)

- A Study of Organizational EffectivenessDocument8 pagesA Study of Organizational EffectivenessRamesh Singh JiNo ratings yet

- Organizational Commitment, Supervisory Commitment, and Employee Outcomes in The Chinese Context: Proximal Hypothesis or Global Hypothesis?Document22 pagesOrganizational Commitment, Supervisory Commitment, and Employee Outcomes in The Chinese Context: Proximal Hypothesis or Global Hypothesis?Phuoc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Allen & Meyer (1990)Document19 pagesAllen & Meyer (1990)Esther D TobariasNo ratings yet

- Allen Meyer 3D OCDocument18 pagesAllen Meyer 3D OCIndra AscendioNo ratings yet

- A Review and Meta Analysis of The AnteceDocument12 pagesA Review and Meta Analysis of The AnteceDarrenNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Job Embeddedness: A Review StudyDocument3 pagesAn Overview of Job Embeddedness: A Review StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational CommitmentDocument29 pagesA Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitmentaghnia nurulNo ratings yet

- Strategic Choice: A Theoretical Analysis: Abstract'Document20 pagesStrategic Choice: A Theoretical Analysis: Abstract'Nuzulul Khaq100% (1)

- Rizzo 1970Document15 pagesRizzo 1970Redita IriawanNo ratings yet

- 20 Perceived Organizational Support and Employee DiligenceDocument9 pages20 Perceived Organizational Support and Employee DiligenceHoneyia SipraNo ratings yet

- Organizational Commitment and Job Performance It's The Nature of The Commitment That CountsDocument6 pagesOrganizational Commitment and Job Performance It's The Nature of The Commitment That CountsPedro Alberto Herrera LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Organizational Commitment in Banking Sector: I J A RDocument7 pagesDeterminants of Organizational Commitment in Banking Sector: I J A RjionNo ratings yet

- Centralization 2Document14 pagesCentralization 2Qasim ButtNo ratings yet

- Beauty Is in The Eye of The Beholder - The Impact of Organizational Identification, Identity, and Image On The Cooperative Behaviors of PhysiciansDocument28 pagesBeauty Is in The Eye of The Beholder - The Impact of Organizational Identification, Identity, and Image On The Cooperative Behaviors of PhysiciansAlper BilgilNo ratings yet

- Testing The "Side-Bet Theory" of Organizational Commitment: Some Methodological ConsiderationsDocument7 pagesTesting The "Side-Bet Theory" of Organizational Commitment: Some Methodological ConsiderationsRuby ChenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 35 - Organizations and Health and Safety: Psychosocial Factors and Organizational ManagementDocument16 pagesChapter 35 - Organizations and Health and Safety: Psychosocial Factors and Organizational ManagementNoor Ul Huda 955-FSS/BSPSY/F17No ratings yet

- Akdere - Azevedo Agency TheoryDocument17 pagesAkdere - Azevedo Agency TheoryNicolas CruzNo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument19 pagesAcademy of ManagementAlmira CitraNo ratings yet

- Final Project OB (7145)Document10 pagesFinal Project OB (7145)Annie MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Meyer (1999) Affective, Normative and Continuance Commitment - Can The 'Right Kind' of Commitment Be ManagedDocument27 pagesMeyer (1999) Affective, Normative and Continuance Commitment - Can The 'Right Kind' of Commitment Be ManagedgedleNo ratings yet

- Wiley Journal of Organizational Behavior: This Content Downloaded From 202.43.93.7 On Tue, 13 Feb 2018 02:54:19 UTCDocument11 pagesWiley Journal of Organizational Behavior: This Content Downloaded From 202.43.93.7 On Tue, 13 Feb 2018 02:54:19 UTCRezky Pratama PutraNo ratings yet

- Barley y Tolbert InstitutionalizationDocument25 pagesBarley y Tolbert InstitutionalizationNanNo ratings yet

- Saam 2007 PDFDocument16 pagesSaam 2007 PDFMega Edvriyanti NingrumNo ratings yet

- 8 - The+management+of+organizational+justice - UnlockedDocument16 pages8 - The+management+of+organizational+justice - UnlockedFelipe Belaustegui IslaNo ratings yet

- Becker 1992Document14 pagesBecker 1992M Yusuf SlatchNo ratings yet

- Oliver 1991 Strategic ResponsesDocument36 pagesOliver 1991 Strategic Responsesjany janssenNo ratings yet

- Developing Stakeholder Theory - Friedman - 2002 - Journal of Management Studies - Wiley Online LibraryDocument21 pagesDeveloping Stakeholder Theory - Friedman - 2002 - Journal of Management Studies - Wiley Online LibrarychanthraboseNo ratings yet

- Bamber Et Al. 1989Document16 pagesBamber Et Al. 1989audria_mh_110967519No ratings yet

- 03 Chien Behaviours PDFDocument4 pages03 Chien Behaviours PDFሻሎም ሃፒ ታዲNo ratings yet

- Social Structural Characteristics of PsyDocument23 pagesSocial Structural Characteristics of PsyYanuar Rahmat hidayatNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 85.201.97.108 On Tue, 11 Apr 2023 22:06:27 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 85.201.97.108 On Tue, 11 Apr 2023 22:06:27 UTCArno Vander SyppeNo ratings yet

- Banking On Ambidexterity A LongitudinalDocument31 pagesBanking On Ambidexterity A LongitudinalAnaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Leadership Styles On Employees' Organizational Commitment in Lithuanian Manufacturing CompaniesDocument10 pagesImpact of Leadership Styles On Employees' Organizational Commitment in Lithuanian Manufacturing CompaniesgedleNo ratings yet

- Wiley Journal of Organizational Behavior: This Content Downloaded From 111.68.97.170 On Mon, 10 Oct 2016 06:14:06 UTCDocument11 pagesWiley Journal of Organizational Behavior: This Content Downloaded From 111.68.97.170 On Mon, 10 Oct 2016 06:14:06 UTCjazi_4uNo ratings yet

- Greenwood, Jennings, Hinings (2015) - Sustainability and Organizational Change PDFDocument33 pagesGreenwood, Jennings, Hinings (2015) - Sustainability and Organizational Change PDFDiana MuslimovaNo ratings yet

- Astannen-Study Organizational EffectivenessDocument7 pagesAstannen-Study Organizational Effectivenessaabha06021984No ratings yet

- Litwin y Stringer - ReviewDocument4 pagesLitwin y Stringer - ReviewAndreaMoscosoContreras100% (1)

- American Accounting AssociationDocument11 pagesAmerican Accounting AssociationVashil SeebaluckNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University Administrative Science QuarterlyDocument27 pagesSage Publications, Inc., Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University Administrative Science Quarterlynatnael denekeNo ratings yet

- PL-7 Target Test ResultsDocument10 pagesPL-7 Target Test ResultsRobert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Ritzer 1969Document5 pagesRitzer 1969Robert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Influence of The Eta Exchange To The Eta Production in Proton-Proton ScatteringDocument6 pagesInfluence of The Eta Exchange To The Eta Production in Proton-Proton ScatteringRobert BagarićNo ratings yet

- IJRR v1n3p143Document7 pagesIJRR v1n3p143Robert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Cyclotron Targetry Production Yields 18FDocument6 pagesCyclotron Targetry Production Yields 18FRobert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Perth CyclotronDocument44 pagesPerth CyclotronRobert BagarićNo ratings yet

- S Parameters An 95 1Document79 pagesS Parameters An 95 1Stephen Dunifer100% (6)

- 8EKR - RF TMP 2Document45 pages8EKR - RF TMP 2Robert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Development of Edutainment-Based Explosion Box Media in Mathematics LearningDocument9 pagesDevelopment of Edutainment-Based Explosion Box Media in Mathematics LearningHasdiNo ratings yet

- Grit DictationDocument3 pagesGrit Dictation우채원No ratings yet

- Humanities (Syllabus 2260) : (Social Studies, Geography)Document44 pagesHumanities (Syllabus 2260) : (Social Studies, Geography)rozaliyalover69No ratings yet

- Intro To OD and Change 2023-25Document16 pagesIntro To OD and Change 2023-25Sharath P VNo ratings yet

- Course Plan RESEARCH WRITING 2 (Curriculum B) Faculty: Ms. Jandell Marcalinas Sections: 11HUMSS8, 11HUMSS7, 11HUMSS1, 11PES1, 11PES2, 11PES3Document7 pagesCourse Plan RESEARCH WRITING 2 (Curriculum B) Faculty: Ms. Jandell Marcalinas Sections: 11HUMSS8, 11HUMSS7, 11HUMSS1, 11PES1, 11PES2, 11PES3MARIA BERNADETT PEPITONo ratings yet

- Conflict Management Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesConflict Management Interview QuestionsAloa SolomonNo ratings yet

- Module Overview-Research MethodsDocument33 pagesModule Overview-Research Methodselijah phiriNo ratings yet

- IT304 Data Warehousing and MiningDocument2 pagesIT304 Data Warehousing and MiningYasyrNo ratings yet

- College Mathematics For Business Economics Life Sciences and Social Sciences 12th Edition Barnett Test BankDocument36 pagesCollege Mathematics For Business Economics Life Sciences and Social Sciences 12th Edition Barnett Test Banklobelincamus.4t8m100% (20)

- Module Research PRELIMDocument38 pagesModule Research PRELIMjhon rey corderoNo ratings yet

- CompReg 20OCTOBER2020Document2,566 pagesCompReg 20OCTOBER2020rajeev_snehaNo ratings yet

- Eng 2 Achievement TestDocument4 pagesEng 2 Achievement TestMernel Joy LacorteNo ratings yet

- PDF MCQS Question Bank No.2 For TY BBA Subject - Research MethodologyDocument18 pagesPDF MCQS Question Bank No.2 For TY BBA Subject - Research MethodologyJAGANNATH PRASADNo ratings yet

- Credit Card Fraud Detection System Using CNNDocument7 pagesCredit Card Fraud Detection System Using CNNIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- DEJUCOSDocument10 pagesDEJUCOSZhira SingNo ratings yet

- GMRC - ReviewerDocument3 pagesGMRC - ReviewerCharley Mhae IslaNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Module - CompressPdf - CompressPdf (2) - CompressPdfDocument131 pagesPractical Research 2 Module - CompressPdf - CompressPdf (2) - CompressPdfYoeded100% (1)

- 1.1 Meaning of Theorem, Lemma, Corollary and ConjectureDocument2 pages1.1 Meaning of Theorem, Lemma, Corollary and ConjectureJOSE ALEJANDRO BELENNo ratings yet

- Practical Research Ii: Happylearni NG With Teacher CamilleDocument39 pagesPractical Research Ii: Happylearni NG With Teacher CamilleSheevonne SuguitanNo ratings yet

- Determinants of The Academic Performance of Student Nurses in San Lorenzo Ruiz College of Ormoc Inc.Document122 pagesDeterminants of The Academic Performance of Student Nurses in San Lorenzo Ruiz College of Ormoc Inc.Jesil MaroliñaNo ratings yet

- Language and GenderDocument2 pagesLanguage and GenderninoNo ratings yet

- Adolescence Anthropological InquiryDocument267 pagesAdolescence Anthropological InquiryRachel CuratoNo ratings yet

- 5 Barriers of CommunicationDocument3 pages5 Barriers of CommunicationShaikhArif88% (16)

- Thesis Statement About Family BondingDocument6 pagesThesis Statement About Family BondingWriteMyPsychologyPaperHuntsville100% (2)

- The Contemporary World Module 2 Lesson 1 Midterm NewDocument6 pagesThe Contemporary World Module 2 Lesson 1 Midterm NewJohn Sebastian GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Survey QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesSurvey QuestionnaireDONALYN SARMIENTONo ratings yet

- Forensic Examination of TypewritingDocument4 pagesForensic Examination of Typewritingcamacam.dahliamarieelysse.oNo ratings yet

- Lepy 106Document23 pagesLepy 106pughalendiranNo ratings yet

- What Is GeographyDocument7 pagesWhat Is GeographyAshleigh WrayNo ratings yet

- BONET, L. e E. NÉGRIER (2018), "The Participative Turn in Cultural Policy", Poetics, 66, Pp. 64-73.Document21 pagesBONET, L. e E. NÉGRIER (2018), "The Participative Turn in Cultural Policy", Poetics, 66, Pp. 64-73.Teresa PaivaNo ratings yet