Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Roots of Renaissance

Uploaded by

Sandhya BossOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Roots of Renaissance

Uploaded by

Sandhya BossCopyright:

Available Formats

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

Social Roots of Renaissance

BA (Hons.) History (University of Delhi)

Studocu is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

Italy during the fifteenth century was the birthplace of the Renaissance. The Renaissance had its

initial flowering in Italy and then spread to other parts of Europe. Italy did not exist as a political

entity in this period. Instead, it was divided into smaller city states and territories: the Kingdom of

Naples controlled the south, the Republic of Florence and the Papal States at the center, the Genoese

and the Milanese to the north and west respectively, and the Venetians to the east. These city states

form an important subject of study as they are representative of a whirlpool of social, economic and

political changes that characterized Renaissance Italy. Burckhardt notes that many of its cities stood

among the ruins of ancient Roman buildings; it seems likely that the classical nature of the

Renaissance was linked to its origin in the Roman Empire's heartland.

In Italy, feudalism was not strong enough and centralised. Amd though it had been the centre of the

Roman Empire, it had never witnessed parcellized sovereignty and fragmentation of land. Northern

and central Italy had an exceptionally large number of towns where urban life was very sophisticated

compared to the rest of Europe. Italy thus developed a polity based on city states. During the 9 th and

10th century, the “commune” gave birth to city-states, whose economy was based on trade and

commerce, and never lost its urban character. As communes got political autonomy, it got charters to

substantiate and legalise this autonomy. Smaller city states or “contado” rose from the commune, and

thus, the city state became the absolute political authority.

The communes which developed was both the cause and effect to a loose centric polity. As in Roman

times, the medieval Italian town lived in close relation to its surrounding rural area, or contado; Italian

city folk seldom relinquished their ties to the land from which they and their families had sprung. The

most powerful groups living in these communes were Grandi, the older elites and the Popolo, the new

emerging elites. Various councils were also emerging at this point like the Council Signoria, oligarchy

of nobles or Grandi’. Popolo were of two types: the Popoplo Grasso (wealthy elites with strong guild

backing) and Popolo Minuti (artists without guild support). The office of Podesta also rose which was

a contractual post given to non-citizens to protect the cities.

In Italy, growing towns demanded self-rule and developed into city-states. Each city consisted of a

powerful city and the surrounding towns and countryside. Italian city-states conducted their own

trade, collected their own taxes, and made their own laws. Some city-states, such as Florence, were

governed by an elected council. During the Renaissance groups of guild members,

called boards, often ruled Italian city-states. Some wealthy families gained long-term control; city-

states were ruled by a single family, such as the Medicis.

Polity and Society

The principal social groups particularly in Florence consisted of three categories. At the top of the

social strata were the ‘first citizens’ or the nobli/prinicpali who monopolised the political power and

kept all the principal posts to themselves. Members of this group were well educated and travelled and

usually lived in the urban spaces. Below the nobli were the people of modest wealth- the mezzani or

populari, the bakers, wine-sellers, artsits, lawyers and civil servants. They however, functioned within

guilds and these guilds had their own distinction and gradation. The top guilds were of cloth

merchants (calimala), wool manufacturers (arte della lana), silk manufacturers (arte della seta) and

bankers (cambio) were monopolised by the grandi. The mezzani were decently educated and the

propertied classes though their participation in the government was limited. The lowest strata

consisted of the poor- the poveri, who also made up the masses. Many of them were domestic servants

or manual workers and some of them also worked in the guild of cloth manufacturers. They were

excluded from political power.

In the late 14th century, there were five important city states- Milan, Venice, Florence, Papal states and

Naples. In 1454 the Peace of Lodi was the first peace treaty signed between these five city states

which organised them into a loose diplomatic alliance. The Lega Italica was a collective defence

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

which would be formed when other city states were attack. This was significant as a situation was

created where no individual ruler could assert complete political authority over the other city states.

The presence of many city states led to a cultural and political competition between them. For Denys

Hay, it was polity of the Italian city states that acted as a stimulus for cultural change. It resulted in

cultural and intellectual diversity fuelled by patronage and a competition among the nobli to hire the

best people for the development of their cities.

If we observe political structures of the city states we note that the autonomy of cities and towns

varied from state to state. Towns might have a considerable degree of independence, for the region

was a loose confederation of some hundreds of different political units, some of them independent

cities. But all cities and towns possessed certain shared characteristics: collective authority exercised

by a group which was selected or elected, and not hereditary. Political historians of the19 th century

saw in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the emergence of phenomenon of ‘modern’ nation states

with a bureaucracy, secular values in public policy and balance of power. Peter Burke referred to it as

the ushering in of a modern age. We shall look at briefly, the history of these city states.

Venice was an important coastal trading centre. Being a republic, it controlled other regions

like Verona, Padua, etc. By the 14th century, the Popolo mercantile faction ruled the city. The

Venetian constitution was celebrated for its stability and balance, thanks to the mixture of

elements from the three main types of government, with the doge representing monarchy, the

Senate aristocracy, and the Great Council democracy. The doge had little power, though he

appeared on the coins and outward respect was paid to him. However, Peter Burke calls this

‘balance’ to be a myth and says that the state had its own share of conflict between these three

power groups.

Florence, the “birthplace of the Renaissance” controlled small city states like Pizza and its

polity can also be recognised as a republic. By the 14th century, the Medici banking family

established firm control of the state. Cosimo de Medici was an early leader and Pope Leo X

also came from the Medicis. However, Florence was witness to political instability and Burke

compares its political system to the dystopia portrayed in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Offices in

Florence rotated more rapidly than those in Venice, the chief magistrates, or Signoria, were in

office for only two months at a time. The minority of Florentines involved in politics was

much larger than in Venice, with more than 6,000 citizens eligible for the chief magistracies

alone.

Milan was the primary trading route to France and Germany. Before the 14 th century, the

Visconti family protected Milan. Francesco Sforza who was hired as Podesta later turned

despotic and the office of Podesta became hereditary. Its primary rival was Venice.

Papal states had their capital in Rome and emerged from a feudal pontifical setup. The pope

was the supreme nominal head but local dukes and nobles also used to rule. During the 14 th

century, the Pope had to leave Rome and the centre of the Papacy was in France, called the

Avignon Papacy. From 1378 to 1417 there was the Great Schism, during which multiple Pope

rose, it was only in the fifteenth century that the Papacy was regained.

Naples was the most targeted area of foreign attack and was organised on feudal lines and had

a hereditary monarchy.

In smaller states like Ferrara, Mantua and Urbino, the key institution was the court and Norbert Elias's

pioneering work on the court culture gives us a key understanding to the roots of the Renaissance.

Courts numbered hundreds of people: in 1527 the papal court, for example, was about 700 strong.

From this point of view, the small circle surrounding Lorenzo de'Medici, the first citizen of a republic,

does not qualify for the title of 'court' at all. This court population was extremely heterogeneous, and

ran from great nobles holding offices such as constable, chamberlain, steward or master of the horse,

through lesser courtiers such as gentlemen of the bedchamber, secretaries and pages right down to

servants. There were also artists, musicians and sculptors who were patronised by the court.

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

The court served two functions- public, where it was the seat of administration and private, where it

was the household of the prince. If the ruler decided to move, an entrouge, which Burke describes as

big as a small town would follow him. The cultural importance of the court as an institution was that

it brought together a number of gentlemen — and ladies — of leisure. It was crucial to what Elias

calls 'the civilizing process'. Like elegant manners, an interest in art and literature developed and

showed the difference between the nobility and ordinary people. Courts existed all over Europe, and

there were city-states, in practice if not always in strict political theory, in Netherlands, Switzerland

and Germany. Courts followed their own decorum, and patronage on the behalf of the scholars was

seen as important according to the records of Baldassare Castiglione.

The Italian historian Federico Chabod asked, 'Was there a Renaissance state?' which he answered in

the affirmative and pointed it to the rise of the bureaucracy. Max Weber substantiates this with his

argument of a patrimonial or bureaucratic state. In brief, a bureaucratic state is formal, impersonal,

where a public space is demarcated and marked by professionals where merit is the base of promotion

and is based on a system of division of labour and law and reason. Some states due to urbanisation

and presence of organisations like the Catholic Church were bureaucratic in nature. There was an

institutional means of preventing officials confusing public and private to their own advantage: the

sindacato. When an official's term of office expired in Florence, Milan and Naples, he had to remain

behind until his activities had been investigated by special commissioners or 'syndics'. It was in

Renaissance Italy that diplomacy first became specialized and professionalized (Mattingly, 1955). The

importance of written records in administration was increasing. The most striking examples of the

collection of information come from the censuses, notably the Florentine catasto of 1427, dealing with

every individual under the rule of the Florentine Signoria.

However, Burke points out that this state though bureaucratic, still ran on loyalty and personal favour.

At the court of Rome, official positions were regularly sold, especially in the reign of Leo X, and the

department of the Datary grew up to deal with this business. Offices were also sold in the states of

Milan and Naples. In Venice, for example, some offices were bought, sold and given as dowries.

Thus, it was important to have connections with the right people at this time, like the Medicis who

received countless letters from people who wanted to gain their support.

Many of the political conflicts of the time were struggles between rival 'factions', in other words

between groups of patrons and clients. Local rivalries continued to give some substance to the

venerable party terms 'Guelf (originally a supporter of the pope) and 'Ghibelline' (a supporter of the

emperor) as late as the sixteenth century. The patronage of artists and writers formed part of this wider

system. The fact that the two great republics, Florence and Venice, were the cities where most artists

and writers originated leads Burke to argue that the arts flourished in these republics since they are

organized on the principle of competition. One might also expect this drive to be stronger in Florence,

where the system was more open, than in Venice, where major public offices were virtually

monopolized by the nobility. In republics there was civic patronage, at its most vigorous in Florence

in the early fifteenth century, when artisans still participated in the government, and Brunelleschi was

elected to one of the highest offices, that of 'prior', in 1425. Civic patronage was weaker in the later

fifteenth century and weaker in Venice than in Florence.

Looking at the social structure of the time, a few factors need to be taken into account- the population

was low in the city-states. Only Naples and Venice had populations crossing 100,000. There were

strong ties to the local part of town individuals were from, the village and neighbourhood became

very important. Official impersonality was hindered by the fact that citizens might know officials in

their private roles. Renaissance Florence seems in some ways more like a village than a city, in the

sense that so many of the artists and writers with whom we are concerned knew one another, often

intimately.

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

However, there was great disparity with regard to income and distribution of wealth. Peter Burke

illustrates how the servant received only 40 lire and the Venetian cardinal, 140,000 lire. Burke

questions if the society was bourgeoisie or not.

The literature of Renaissance Italy suggests a society which was unusually concerned with social

mobility. Individual cases of upward mobility are striking. Nicholas V, the so-called 'humanist pope',

lived in poverty in his student days, although he was the son of a professional man, a physician.

Bartolommeo della Scala was a miller's son who became chancellor of Florence. There was

considerable interest in ancient Greek and Roman examples of men of humble origins rising to high

place. However, this theory has been contested by later American scholars and Burke also accounts

that the evidence is indeed fragmentary at this stage. All the same there are good reasons for asserting

that social mobility was relatively high in the cities of fifteenth-century Italy, and above all in early

fifteenth-century Florence, with 'new men' coming in from the countryside and becoming citizens and

holding office which alarmed the old nobility. By the later fifteenth century, however, the ranks had

closed. In Venice itself there was little opportunity for new men to enter the patriciate throughout the

period, whatever mobility there may have been at lower levels.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Italy was one of the most highly urban societies in Europe. In

1550, about 40 Italian towns had a population of 10,000 or more. Of these, about 20 had a population

of 25,000 or more, including Milan, Rome, Venice and Naples. In the rest of Europe, from Lisbon to

Moscow, there were probably no more than another 20 towns of this size. It must not be assumed that

all these townsmen were bourgeois. Renaissance Florence and other cities rested on the backs of what

contemporaries called the popolo minuto, the 'labouring classes'. All the same, the relative importance

of Italian towns is obviously linked with the relative importance of merchants, professional men,

craftsmen and shop-keepers. All these groups are sometimes called 'bourgeois'; none of them fits the

traditional model of a society divided into clergy, nobles and peasants. Machiavelli is a master of

political calculation, but he expressed contempt for Florence as a city governed by shop-keepers and

he described himself as 'unable to talk about gains and losses, about the silk-guild or the wool-guild'.

There are other links between the social structure of Renaissance Italy and its art and literature. The

importance of the lineage and the value set upon its cohesion, in noble and patrician circles at least,

helps explain the importance of the family chapel and its tombs, the focus of a kind of ancestor

worship. Large sums of money were spent on palaces partly because they were a symbol of the

greatness of the 'house' in the sense of the family. On the other hand, a breakdown of the cohesiveness

of the extended family may well have encouraged Renaissance 'individualism'. The idea of patronage

was a very important aspect of the Renaissance, which was often motive driven. Guilds, nobles,

municipality and churches were important patrons. There were two kinds of systems of patronage-

scholars and artists who could work generally on a regular basis for the patron, and creative artist and

scholars like da Vinci who had to be hired.

There were two interesting trends noticed in the arts. One was classism wherein, classical knowledge,

that is from Greco-Roman texts was taken as the highest form of knowledge, and the Classical form

was also imbibed in the painting style and structure. There was also a move, called scholasticism

which brought in Christian theology- logic was applied in the manner prescribed by the Aristotelian

school and became a form of studies.

The ambiguous status of the painter, the musician and even, to some extent, of the humanist are

special cases of a more general problem: that of finding a place in the social structure for everyone

who was not a priest, warrior or peasant. If the status of the artist was ambiguous, so was that of the

merchant. It is probably no mere coincidence that it was in cities of shop-keepers, Florence in

particular, that the artist was accepted most easily. It was easier for the artist to excel with the right

patronage. Thus, it is no surprise to find a relatively mobile society like Florence associated with

respect for achievement and also with a high degree of creativity.

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

Economy: Robert Lopez was the earliest writer to see economic and cultural growth as an inverse

thesis, and said due to economic stagnation between 1350s to 1520s, wealth was distributed equally.

Long distance trade declined, and the only option that was there was to develop culture through

patronage of art and architecture to gain status. Carlo Cippolla also agrees that trade and commerce

was on the decline bur he criticises Lopez on basing his argument on limited sources. Centres like

Florence didn’t experience decline, and hence, it want a general decline, he believed that it was a

decline in population and hence, demographic factors which led to an increase in the standard of

living.

Economic changes were integral to these states in bringing about a new and changing context for the

cultural movement. There was a commercial revolution in economy with the destruction of the old

feudal system and the emergence of a new elite based on wealth rather than birth. Social and

economic changes were a necessary prelude to the Renaissance. These changes can be seen as part of

the great expansion of 1000-1300, which was accompanied by the monetarization of the economy,

commercialization and growth of industry. The leading sectors in development after the11 th century

were towns, and international trade. In the 13th century, much of Europe experienced strong economic

growth. By the 15th century, cities such as Florence and Venice had achieved material and artistic

sophistication. According to Hale, the Italian economy began to decline starting even in the14 th

century when there was a decline of communes, establishment of signori, decline in social life,

alienation of classes from public administration, political adherences and favoring of tradition over

merit and initiative. In fact, as Hale explains, that the second half of the16 th century was called the

Indian Summer of the Italian economy.

We now look briefly at what were the elements that led to the commercial revolution. The principle

factor was the emergence of commerce and banking. In the13 th century states like Piacenza and Lucca

took the lead in establishing business connections. The travelling merchant was replaced by the

sedentary businessman who operated through agents. By 1300, Italian mercantile and banking

companies were set up all across Europe in cities like Paris. Italy became the birthplace of innovations

in business techniques, organization of fairs, manuals of commerce, techniques of accounting, check,

double entry book-keeping, joint stock companies, systematized foreign exchange market

governmental endorsement and marine and land insurance. There were other financial devices also

like arrangements for sharing profits with partners or depositors, accounting systems, letters of

exchange etc. There was an efficient system of mail with the use of private and company letters and

couriers for contact and notarized agreements. There was a building up of uniform customs and rules

of law as the spread of Italian business methods took place all over Levant and Western Europe. The

existence of these institutions encouraged a mode of thought characterized by numerate mentality.

As a result, banking became an Italian specialty. The leading firms were Bardi, Peruzzi, Naples etc.

Banking and credit were the most rewarding forms of investment. Credit operations included loans to

government; bankers came to dominate business of exchange in 16 th century Europe. There were also

communal pawnshops, which could borrow and lend money with the pay of a regular interest.

Florence also had something called a dowry fund where the investor received money back with

interest on marriage of daughter. It was also possible to insure against loss of ships in Venice

especially. In Genoa on the wife’s death in childbirth.

We now turn attention to trade which was integral to urban revolution. The Crusades had built lasting

trade links to the Levant, and the Fourth Crusade had done much to destroy the Byzantine Empire as a

commercial rival to the Venetians and Genoese. The main trade routes from the east passed through

the Byzantine Empire or the Arab lands and onwards to the ports of Genoa, Pisa, and Venice. Luxury

goods bought in the Levant, such as spices, dyes, and silks were imported to Italy and then resold

throughout Europe. From France, Germany, and the Low Countries, through the medium of the

Champagne fairs, land and river trade routes brought goods such as wool, wheat, and precious metals

into the region. The extensive trade that stretched from Egypt to the Baltic generated substantial

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

surpluses that allowed significant investment in mining and agriculture. Thus, while northern Italy

was not richer in resources than many other parts of Europe, the level of development, stimulated by

trade, allowed it to prosper. The trade routes of the Italian states linked with those of established

Mediterranean ports and eventually the Hanseatic League of the Baltic and northern regions of Europe

created a network economy in Europe for the first time since the 4th century. Florence became the

centre of this financial industry and the gold florin became the main currency of international trade.

Towns were the main center of the commercial revolution as urban life contributed to commerce.

Cities and towns were centers of wealth production and of creativity. In the 10 th century the first

mercantile towns such as Bari came up. By the end of the 11 th century, the crusades led to the

development of maritime cities of Northern Italy, Venice Pisa and Genoa who were engaged in trade

with areas like the eastern Mediterranean which brought wealth to towns Expenditure was not just a

personal matter; it was a matter of corporate status as well. In the towns that emerged we look at the

importance of new families from among wealthy merchant bankers and industrialists who dominated

the city’s politics. The new mercantile governing class, who gained their position through financial

skill, adapted to their purposes the feudal aristocratic model that had dominated Europe in the Middle

Ages. In much of the region, the landed nobility was poorer than the urban patriarchs in the High

Medieval money economy whose inflationary rise left land-holding aristocrats impoverished. The

decline of feudalism and the rise of cities influenced each other; for example, the demand for luxury

goods led to an increase in trade, which led to greater numbers of tradesmen becoming wealthy, who,

in turn, demanded more luxury goods

The siting of the major urban centers of Renaissance Italy owed a good deal to the communication

system inherited partly from nature and partly from ancient Rome, Genoa, Venice, Rimini, Pesaro,

Naples, Palermo. Rivers were the easiest way to move goods so towns along the rivers grew as

important trade centers also. The Danube, Rhone and Rhine rivers all became important trade routes

and the towns along their banks grew. The towns also developed in response to demands from other

places for which services were performed. In pre-industrial Europe, Burke distinguishes three types of

service and city. The first kind is a commerce city with a port, like Venice. The second is a craft-

industrial town, like Milan or Florence. The third is a service city, which is most profitable.

The fact that towns were larger and more numerous in Italy than elsewhere does a good deal to

explain the importance in the social structure of the different 'middle classes', such as the craftsmen,

merchants and lawyers. Once established, towns were able to maintain their position by their

economic policies. Cities generally controlled the countryside around them, their contado, and they

might enforce at the expense of the countryside a policy of cheap food for their own inhabitants. The

contado was also forced to pay more than its share of tax, which must have been an incentive for the

more prosperous peasants to migrate to the city. Citizens also enjoyed legal and political privileges

which inhabitants of the countryside lacked.

There was a lot of migratory movement of population, with an influx from rural areas. The reason for

this was attraction and repulsion; the “frontier” was a new and dynamic world which could break ties

with an unpleasant past and had opportunities for economic and social success. The town would fill

with people who left the feudal world without regret. The walls of the town became a boundary

between two cultures in conflict. The cities controlled the countryside around them, their Contado, at

the expense of the country. The Contado paid more than its share of taxes which became an incentive

for prosperous peasants to migrate. Citizens had political and legal privilege which inhabitants of the

country lacked. Pregnant women from Lycca would travel to the city so that their children would be

born in city.

Despite the growing importance of grain imports urban structure rested on foundation of agriculture

particularly the fertile Po valley. By 1500, 85% of land between Pavia and Cremona was under

cultivation. Dairy farming was becoming important. South of Po valley picture is less rosy. By 14 th

and 15th centuries it was going out of cultivation with 10 % villages disappearing. Southern

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|20323511

agriculture was in decline and the landlords abandoned estates to the managers’ care in order to settle

down in the towns. Economic oragnisation in the towns, according to Burke, remained traditional with

small workshop within a family business. Economic oragnisation within towns was usually through

guilds. Within the guild, masters protected their position against apprentices and journeymen; the very

small scale of most industry facilitated this kind of control. Relationships between guilds were also far

from equal. Merchants belonged to elite guilds whose economic power was protected by the urban

government (which of course they constituted) or the state; artisans belonged to less prestigious guilds

which had far less stake in urban government and whose activities were closely overseen by the urban

magistrates.

One important question discussed by Burke is whether the economy is capitalist. There were rich

entrepreneurs like Averardo Di Bicci De Medici which showed that it was possible to accumulate

wealth. As in some leading industries like cloth many workers were employed who were no longer

independent craftsmen. There was a division of labour of the most highly developed kind involving

men who were paid by day. In Genoa and Lucca, silk merchants provided raw material and spinning

machines which were hired out to spinners and looms to weavers. This system was different from the

industrial capitalism of the 19th century as it was not large scale and lacked direct control of

manufacturer but it was clear that the manufacturer played a central role in the control by indirect

means.

Downloaded by Sandhya Boss (sandhyaboss076@gmail.com)

You might also like

- Chapter 2 Notes - Renaissance and DiscoveryDocument23 pagesChapter 2 Notes - Renaissance and Discoveryapi-324512227100% (1)

- Chapter 12 AP EURO WESTERN CIVILIZATIONDocument15 pagesChapter 12 AP EURO WESTERN CIVILIZATIONRosecela Semedo0% (1)

- Leijiverse Integrated Timeline - Harlock Galaxy Express Star Blazers YamatoDocument149 pagesLeijiverse Integrated Timeline - Harlock Galaxy Express Star Blazers Yamatokcykim4100% (3)

- Venetian ConstitutionDocument39 pagesVenetian ConstitutionPararo ParelNo ratings yet

- On the Medieval Origins of the Modern StateFrom EverandOn the Medieval Origins of the Modern StateRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Prep 2015Document792 pagesPrep 2015Imran A. IsaacNo ratings yet

- Paul Stockman - PsyclockDocument7 pagesPaul Stockman - Psyclockseridj islemNo ratings yet

- Global Supply Chain M11207Document4 pagesGlobal Supply Chain M11207Anonymous VVSLkDOAC133% (3)

- Italian City States During Renaissance in EuropeDocument3 pagesItalian City States During Renaissance in EuropeRamita Udayashankar50% (4)

- Ap® Focus & Annotated Chapter OutlineDocument11 pagesAp® Focus & Annotated Chapter OutlineEllie GriffinNo ratings yet

- The MediciDocument14 pagesThe Medicigmicheliv0% (1)

- Proto-Renaissance 1300-1400Document6 pagesProto-Renaissance 1300-1400Neyder Andres Ramirez HenaoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Study GuideDocument6 pagesChapter 13 Study GuideMauricio PavanoNo ratings yet

- Kehs107 PDFDocument21 pagesKehs107 PDFMaithri MurthyNo ratings yet

- Changing Cultural Traditions: ThemeDocument16 pagesChanging Cultural Traditions: ThemeGaurav RathiNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Day 2Document3 pagesUnit 1 - Day 2Sally YuNo ratings yet

- Palazzo EssayDocument5 pagesPalazzo Essayapi-394499283No ratings yet

- Chapter 12 OutlineDocument14 pagesChapter 12 OutlineGabriel LeeNo ratings yet

- Martines Lauro Political Conflict in The Italian City StatesDocument23 pagesMartines Lauro Political Conflict in The Italian City StatesAnnikaNo ratings yet

- Ap Euro Chapter 12Document11 pagesAp Euro Chapter 12MelindaNo ratings yet

- Florence: Its History, Its Art, Its Landmarks: The Cultured TravelerFrom EverandFlorence: Its History, Its Art, Its Landmarks: The Cultured TravelerNo ratings yet

- Autonomy and Identity in The Cities of Norman ItalyDocument10 pagesAutonomy and Identity in The Cities of Norman ItalybaredineNo ratings yet

- AP Euro History, CH 12, CurrentDocument134 pagesAP Euro History, CH 12, CurrentHeather FongNo ratings yet

- DIPLOMACY - From Inception To 1914 (Louis J Nigro JR 2010)Document13 pagesDIPLOMACY - From Inception To 1914 (Louis J Nigro JR 2010)Alexa Strimbu0% (1)

- HC - RenaissanceDocument25 pagesHC - RenaissanceJinal PatelNo ratings yet

- Renaissance CultureDocument6 pagesRenaissance Culturebhawnamehra2804No ratings yet

- History RenaissanceDocument13 pagesHistory RenaissanceVi MiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Notes - Renaissance and DiscoveryDocument14 pagesChapter 10 Notes - Renaissance and DiscoveryAlice YangNo ratings yet

- Theory and Practice of Modern Diplomacy - Origins and Development To 1914Document14 pagesTheory and Practice of Modern Diplomacy - Origins and Development To 1914IoanaAnisiaNo ratings yet

- Renaissance 04Document10 pagesRenaissance 041913 Amit YadavNo ratings yet

- Handout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyDocument35 pagesHandout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyJemal SeidNo ratings yet

- Florence in The RenaissanceDocument27 pagesFlorence in The Renaissanceelianabereket.556No ratings yet

- Reading - History of Modern StateDocument5 pagesReading - History of Modern Stateonoffon.No ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument9 pagesEconomicsevangeline.brichauxsNo ratings yet

- Reading Unit 1Document4 pagesReading Unit 1Diem PhamNo ratings yet

- CH 10 TermsDocument3 pagesCH 10 TermsRahul MishraNo ratings yet

- Study Guide to The Prince and Other Works by Niccolò MachiavelliFrom EverandStudy Guide to The Prince and Other Works by Niccolò MachiavelliNo ratings yet

- Copy Unification of Italy 1815-18485Document27 pagesCopy Unification of Italy 1815-18485munashezawaniNo ratings yet

- AP European Chapter 10 NotesDocument5 pagesAP European Chapter 10 NotesIvan AngNo ratings yet

- Origin Modern StatesDocument8 pagesOrigin Modern StatesRommel Roy RomanillosNo ratings yet

- Records Politics and Diplomacy SecretariDocument21 pagesRecords Politics and Diplomacy Secretarimiska.sutovskaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Diplomacy: New DiplomatDocument3 pagesA Brief History of Diplomacy: New DiplomatuvunitNo ratings yet

- Changing Cultural Traditions in Europe 1300-1800Document16 pagesChanging Cultural Traditions in Europe 1300-1800soundu ranganath100% (1)

- Companion To Baroque MusicDocument143 pagesCompanion To Baroque MusicIgor Correia100% (1)

- European History - The Crises of The Middle AgesDocument9 pagesEuropean History - The Crises of The Middle AgeslastspectralNo ratings yet

- Princes of the Renaissance: The Hidden Power Behind an Artistic RevolutionFrom EverandPrinces of the Renaissance: The Hidden Power Behind an Artistic RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Chapter 20 Lesson 1 PDFDocument3 pagesChapter 20 Lesson 1 PDFAdrian Serapio100% (1)

- History Easy To Learn Grade 10. 2023-24Document25 pagesHistory Easy To Learn Grade 10. 2023-24shanzathekkoth7No ratings yet

- Florence and Its Church in the Age of DanteFrom EverandFlorence and Its Church in the Age of DanteRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- IGNOU World History NotesDocument429 pagesIGNOU World History NotesRavinder Singh Atwal75% (8)

- Chapter 13 Western CivilizationDocument6 pagesChapter 13 Western Civilizationnie xunNo ratings yet

- UNIT 1 - The 18 Century in Europe: Absolute MonarchyDocument14 pagesUNIT 1 - The 18 Century in Europe: Absolute MonarchyBoom GT GamesNo ratings yet

- The Village Labourer, 1760-1832 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study in the Government of England Before the Reform BillFrom EverandThe Village Labourer, 1760-1832 (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study in the Government of England Before the Reform BillNo ratings yet

- History Stuff IdkDocument44 pagesHistory Stuff IdkNina K. ReidNo ratings yet

- RinascimentoDocument3 pagesRinascimentogdellatorre09No ratings yet

- Renaissance in Italy (1375-1527) : Reading Notes 317-326Document2 pagesRenaissance in Italy (1375-1527) : Reading Notes 317-326Ivan AngNo ratings yet

- The Origins of The French Revolution: A Tale of Two Cities'Document6 pagesThe Origins of The French Revolution: A Tale of Two Cities'Sujatha MenonNo ratings yet

- How Venice Rigged The First, and Worst, Global Financial CollapseDocument13 pagesHow Venice Rigged The First, and Worst, Global Financial CollapseOnder-KofferNo ratings yet

- Nicolo Machiavelli WikiDocument21 pagesNicolo Machiavelli WikiPhạm Xuân DũngNo ratings yet

- The Battle of April 19, 1775Document298 pagesThe Battle of April 19, 1775John SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Example 1: Analytical Exposition TextDocument1 pageExample 1: Analytical Exposition Textlenni marianaNo ratings yet

- M&D OutlineDocument6 pagesM&D Outlineyared100% (1)

- CAF 8 AUD Autumn 2022Document3 pagesCAF 8 AUD Autumn 2022Huma BashirNo ratings yet

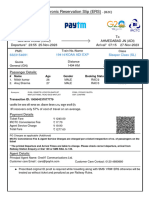

- Train TicketDocument2 pagesTrain TicketSunil kumarNo ratings yet

- JTMK JW Kelas Kuatkuasa 29jan2024Document20 pagesJTMK JW Kelas Kuatkuasa 29jan2024KHUESHALL A/L SRI SHANKAR LINGAMNo ratings yet

- 3D Laser ScannerDocument100 pages3D Laser ScannerVojta5100% (1)

- Midnight in The City of Brass v22Document87 pagesMidnight in The City of Brass v22MagicalflyingcowNo ratings yet

- Design and Monitoring of Water Level System Using Sensor TechnologyDocument3 pagesDesign and Monitoring of Water Level System Using Sensor TechnologyIJSTENo ratings yet

- Whatever Happened To Great Movie Music?Document35 pagesWhatever Happened To Great Movie Music?AngelaNo ratings yet

- DEC Aluminium FormworkDocument14 pagesDEC Aluminium Formwork3mformcareNo ratings yet

- North West Karnataka Road Transport Corporation: (Application For Student Bus Pass)Document3 pagesNorth West Karnataka Road Transport Corporation: (Application For Student Bus Pass)RasoolkhanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: QualificatonDocument4 pagesCurriculum Vitae: QualificatonAhmad Ali Shah ShaikNo ratings yet

- FE Lab 1Document23 pagesFE Lab 1patrickNX9420No ratings yet

- Membership Structure Iosh 2016Document1 pageMembership Structure Iosh 2016Deepu RavikumarNo ratings yet

- Ksa 2211 Kiswahili Sociolinguisticscu 4CH 60Document2 pagesKsa 2211 Kiswahili Sociolinguisticscu 4CH 60Akandwanaho FagilNo ratings yet

- T&D FinalDocument69 pagesT&D Finalthella deva prasadNo ratings yet

- 01 Award in Algebra Level 2 Practice PaperDocument20 pages01 Award in Algebra Level 2 Practice Papershazanajan921No ratings yet

- Gold Exp B1P U4 Skills Test BDocument6 pagesGold Exp B1P U4 Skills Test BVanina BuonagennaNo ratings yet

- GUIA Inglés 2 ADV ExtraordinarioDocument2 pagesGUIA Inglés 2 ADV ExtraordinarioPaulo GallegosNo ratings yet

- BRD8025 DDocument24 pagesBRD8025 Dsluz2000No ratings yet

- Assetto Corsa Modding Manual 3.0 - 0.34revdDocument702 pagesAssetto Corsa Modding Manual 3.0 - 0.34revdmentecuriosadejimmy100% (1)

- The Impact of Students Behaviors To The Teachers Teaching MethodDocument32 pagesThe Impact of Students Behaviors To The Teachers Teaching MethodAaron FerrerNo ratings yet

- Ekanade Et Al - NigeriaDocument9 pagesEkanade Et Al - NigeriammacmacNo ratings yet

- GE RT 3200 Advantage III Quick GuideDocument78 pagesGE RT 3200 Advantage III Quick GuideluisNo ratings yet

- Valeroso vs. CA Case DigestDocument1 pageValeroso vs. CA Case DigestMarivic Veneracion100% (2)