Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bole Butake - Nkiendah's Red Eyes (1980) (10.2307 - 3043932)

Bole Butake - Nkiendah's Red Eyes (1980) (10.2307 - 3043932)

Uploaded by

TALBA BAISSANAOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bole Butake - Nkiendah's Red Eyes (1980) (10.2307 - 3043932)

Bole Butake - Nkiendah's Red Eyes (1980) (10.2307 - 3043932)

Uploaded by

TALBA BAISSANACopyright:

Available Formats

Nkiendah's Red Eyes

Author(s): Bole Butake

Source: Callaloo, No. 8/10 (Feb. - Oct., 1980), pp. 79-86

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3043932 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 08:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Callaloo.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

79

NKIENDAH'S RED EYES

by Bole Butake

"Red eyes will bring about your death; you this child. How can it be

that you are never satisfied with what you are given? You eat and

wipe your mouth like the fowl does and still looks as hungry as ever.

You will see what greed will do to you some day," Mama Fijoi used to

tell her son, Nkiendah, way back in his childhood.

Today Nkiendah remembered his mother's words because he was

several hundred kilometres away from his village looking for a man

who might not even exist. If he were alone things might be different.

But he was with his daughter, Yiwsi; and he had come this long dis-

tance to give her hand in marriage to a man who claimed to be a big

government servant in a big office in Kumba. Nkiendah had never

seen or heard of this man; but he had promised wonders. "Even if this

small sum of money is not enough for the transport fare borrow more

and come down as soon as you receive this letter. Money is not the

problem; but I am dying to see Yiwsi and, of course, you." It was only

after Nkiendah and his daughter had been looking for the man called

Thomas Wanti of Divisional Office, Kumba, for two days that for the

first time in his life he began to think about his predicament.

If this man loved his daughter as much as he claimed in that letter,

Nkiendah wondered, why didn't he come and see him in his own com-

pound as was the custom? For the first time he realised that there was

something smelly about that letter. The envelope was in Nkiendah's

name; but the letter itself was in the name of his daughter. In the letter

Thomas Wanti would address himself to Yiwsi at one moment and to

Nkiendah the very next instance. But in that condition of great excite-

ment Nkiendah could not suspect anything. Yiwsi was ready to go

with any plan so long as she would be released from the forced deten-

tion under which her father had placed her. In fact she was planning to

escape from this Thomas Wanti and join Sama Ndifon wherever he

might be. She couldn't bear to stay away from her son.

Yes, late Mama Fijoi was right when she said Nkiendah would see

what his greed would lead him to. Those red eyes of his were even the

cause of her death. And now, here they were stranded in Kumba be-

cause of his red eyes. For the first time in his life Nkiendah agreed with

the rest of the world that one can only void in the same measure as one

eats. He had to. So many hundred kilometres away from his village

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

80

and a daughter on his back and no transport money to go back home!

They had been looking for this Thomas Wanti for two days now, and

there was no longer any doubt that no such person existed in Kumba.

Nobody by that name had ever worked in the Kumba Divisional Of-

fice, and no Oku man had ever heard of him. He had claimed in his

letter that he was a true born of Oku, the third son of Pa Wanti of

Njikijem. All the Oku elements in Kumba knew each other, and many

of them knew Pa Wanti. But they all said he didn't have a son working

anywhere in the government service. All of his sons were back in the

village cutting down a whole forest and planting coffee. None of them

had ever seen the four walls of a school and they were all married. In

fact the youngest of them was Nkiendah's age-mate and he too had re-

cently married off his daughter to some big teacher in the village.

Nkiendah now saw his plight very clearly. His mother was right

when she often said that he would one day live the reward of his

greed. It was also very true what the elders said: A dog that chases too

much will one day catch a viper. If he had not been such a red-eyed

glutton he would never have demanded so much from Yiwsi's hus-

band; she would never have returned to the compound with their son;

the letter would never have been received; and they would never have

left the village for Kumba to look for Thomas Wanti who did not

exist. Yes, a dog that chases too much will one day catch a viper. He

had, at last, caught a viper. And here they were marooned in Kumba:

no money to pay the fare back to the village. It meant ten thousand

francs for both of them, and they would barely arrive. They would

have to live on charity. If they hadn't found their country man, Pa

Toma, they would probably be sleeping on the road. Nkiendah did

not want to think of the five thousand francs he had borrowed from

his neighbor, Pa Lanyam. If only he could get back home he would of-

fer a suitable holocaust to the ancestors. He had neglected them all

these years just because of his greed. He now believed that his mother,

Mama Fijoi, must be behind this misfortune which had befallen him.

Hadn't he been responsible for her death? Just because he knew that

the woman could not be taken away from him after that last cere-

mony?

Nkiendah had, indeed, done a terrible thing to his in-laws. Such

baseness had never been heard of in the whole clan and Mama Fijoi

had died of the shock. It was the last oil known as the oil for the home-

coming in respect of Yiwsi's mother. All of the bride-wealth had al-

ready been paid and all that remained was two tins of palm-oil for the

home-coming. Nkiendah's uncle, Pa Gayi, had bought the two tins of

oil and instructed him to take them to his in-laws. On the eve of the

home-coming, Nkiendah looked at the two tins of oil and his eyes

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

81

grew large and red. If he gave away all the oil what would the woman

use in cooking his food? What they had given away to the in-laws was

already too much! After all, the woman was coming home finally and,

no matter what happened, her family would not dare to take her back.

So Nkiendah had procured an empty tin and filled it half way with

water and then topped it with oil. Then he poured some water into the

other tin until the oil showed at the mouth. He sealed both tins up

very carefully with banana fibre and took them to his in-laws early in

the morning. That night he received his bride and forgot about his

dirty trick.

Two weeks later Mama Fijoi was summoned by her in-laws rather

urgently. She found Ntumla's mother and Ma Nkainen sitting by the

fire-side, talking in low tones. As soon as the usual greetings were ex-

changed Ntumla's mother brought down a large pot from the ceiling

and fetched the two tins of oil from a corner of the house. Then Ma

Nkainen spoke:

"We were just saying that you too should come and see what our

own eyes are seeing. Sometimes when you are working in the farm

alone you can confuse the headless snake, giver of children, for an

earthworm and do it some harm. So it is always good to call a neigh-

bour and see whether she has something else to say." Then, turning to

Ntumla's mother she said, "Mbo'oh, pour the oil into the pot."

When Ntumla's mother began to pour the oil into the pot, Mama

Fijoi thought she was dreaming. She pinched her thigh and wiped her

eyes with the hump of her right thumb. After the water came the oil,

and Mama Fijoi could not understand.

"Is this water or oil?" she wondered aloud.

"That is the same question we are asking ourselves," Ma Nkainen

replied.

"But, as you see, only the ancestors know whether this is water or

oil. Is this the way you people celebrate the home-coming of the bride

in your compound?"

"Who brought this oil?" Mama Fijoi heard herself ask.

"Who else? The husband of Ntumla, of course," Ma Nkainen an-

swered.

There was no longer any doubt as to what had happened. Mama

Fijoi cried from there until she got back to her compound. This is what

her son's greed had come to. She didn't understand how a man could

still be greedy, even when it came to his own wife. As soon as she got

to the compound she went into Nkiendah's house and began to search.

She soon found the tin of oil under his bed, hidden away in the darkest

corner.

From that day Mama Fijoi was no longer herself. The shame, the

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82

disgrace, was too much to bear. She lost the drive to live and withered

away like a weed in the sun. Three months later she died.

Nkiendah's greed was the death of his mother, which he didn't even

bother to honour with befitting sacrifices and ceremonies. He instead

saw this death as the removal of that other voice which was always re-

minding him about his red eyes, his greed. Now that she was no more

he would be free to go about his business unperturbed.

Yiwsi was his first child, and he became very attached to her. After

her came five other children, all of them boys, who were now pester-

ing him about clothes, books and school-fees.

Then Sama Ndifon came along saying he wanted to marry Yiwsi.

He was a very intelligent man but had not gone beyond Standard Six

in his education. He also travelled a lot and had gone all over Nigeria

and most of Cameroon. He had worked in all sorts of places but never

managed to keep steady at any one job. Either he challenged the au-

thority of his boss or defrauded the service of something and got

sacked. But he never went to prison. Nobody was ever clever enough

to pin a charge on him that would lead to his being convicted. He was

a smart fellow, Sam Ndifon.

So he once came back home and saw Yiwsi and loved her. Everyone

in the clan knew what red eyes Nkiendah had and advised Sama

Ndifon to look elsewhere. A fly can never carry a lump of shit, they

said. It can only strut about on it and fly off with dirty feet. But Sama

Ndifon would have Yiwsi or no other girl in the village. He loaded

Nkiendah with gifts and money until he thought he had given more

than enough. Then he went to his in-law and asked to fix a day on

which both families should discuss the matter and come to some con-

clusion concerning the home-coming oil.

"Eh? Home-coming oil already?" Nkiendah ejaculated. "What

makes you think it is time for the home-coming oil? You think my

daughter is an orphan to be given away like that?"

"Ba'a, do you mean that you have not had enough yet?" Ndifon was

completely confounded. He now understood why his family had

warned him against Nkiendah. He had been to see him on three occa-

sions, each time with two or three members of his family. There was

always the traditional wine and presents for the bride's family. But on

none of these occasions had they found Nkiendah with any other

member of his own family. He always said that he was the head of the

family and so did not need a crowd to settle a little problem of giving

out a daughter in marriage. Now, it was clear to Ndifon that Nkien-

dah was determined to make the greatest profit out of the deal. But he

was not the type to be cheated by a greedy village tortoise in the shape

of Nkiendah.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

83

"You know that according to our custom I have already gone way

beyond the stipulated bride-wealth just because I thought that marry-

ing a woman is not like buying a cow off a Fulani man. You know also

that our people say you never finish paying the price for a bride. So

just fix the date for the home-coming oil so that I can claim my bride."

"Yes, I will tell you when the time comes," Nkiendah said calmly.

"Where have you ever heard that a man who lives by the river washed

his hands with spittle? I will tell you when the time comes."

There was nothing more to say. So Sama Ndifon left with a promise

to come back any time he had something. That promise came from the

mouth only. For, in his heart, he was at that moment taking a solemn

oath never to give anything more to Nkiendah or any of his kinsmen

on Yiwsi's head.

He was a travelling man and had hoped to go away this time with a

wife honourably given to him by her family. But as things now stood

he would have to use his brains to be able to go away with Yiwsi. On

the following day of rest when she brought him food, he told her that

her father had refused to fix the day for the home-coming oil.

"Buthow can he do that? What reason did he give?" Yiwsi inquired.

"He says he can't live on the banks of the Kibanya and wash his

hands with spittle."

"Is that what he says? So he hasn't eaten enough from you yet? He is

my father but he has very big eyes. I will be no party to his greed."

"I am leaving for Nkongsamba next market day, in five days. I have

been putting off the journey because I thought we might leave to-

gether. But now your father wants to marry you himself."

"And what becomes of me? You think I will stay behind and be

laughed at by friends? The whole village will be saying that I am in

support of his behavior."

"We will leave together then. But don't whisper it even to the grass.

If he knows that I am about to leave he will lock you up in the house

until several weeks after my departure."

Five days later Sama Ndifon and Yiwsi had eloped, and Nkiendah

was so angry that he could have cut someone down with his matchet.

He kept swearing that the day Yiwsi came back she would not spend a

single night in Ndifon's compound.

Sama Ndifon had always held that a true born of the clan must al-

ways return to his people at least once every year. He had rigorously

observed this rule until his elopement with Yiwsi. Then he found him-

self staying away from the village for four years! He and his wife had

had a son who was now three years old, and she was even more anx-

ious than he was to see her mother and show her the son who was al-

ready growing into a man. Both of them believed that the sight of a

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84

three-year old son would so please Nkiendah that he would forget the

past and bless the marriage. But no. As soon as they got to the village,

Nkiendah descended upon them like a kite and made off with his

daughter and grandson.

For four consecutive weeks, Sama Ndif on, to no avail, tried by him-

self and through emissaries to make Nkiendah see reason and recog-

nise the marriage. Yiwsi's father only insisted on the fact that his

daughter had been stolen from him and that whatever he had received

before was not enough compensation for the crime. He kept his

daughter under firm guard and made it known that if he as much as

heard that she ever left the compound for no good reason he would

pull out her eyes with his tapping-knife. In short, as far as he was con-

cerned, there could never be talk again of her being Sama Ndifon's

wife.

After two months Sama Ndifon came to live with the fact that Yiwsi

could never become his truly married wife. So he again opened up

contacts to reclaim his son, Ntumfon, whom he loved dearly. But Nki-

endah would not hear of it. And Ndifon would not accept to lose both

mother and son.

He spent sleepless nights trying to figure out how to recover his only

offspring. He believed very firmly that the hawk can never catch an

only chick. He knew that Nkiendah's greatest weakness was the lust

for money. He also knew that nobody in the whole clan would dare to

ask Yiwsi's hand in marriage again after what had happened to him.

He had been the only one foolish enough to put his hand into the fire

in spite of the warnings. But everyone else in the clan knew Nkiendah

for his red eyes. Six months passed and no one came near Nkiendah's

compound to ask after his daughter Yiwsi, who had returned from the

world of civilisation looking even younger and more beautiful than

when she had left the village a few years back.

Meanwhile, Sama Ndif on had, at last, settled on a line of action

which he hoped would succeed. One day he suddenly disappeared

from the village. Nobody knew where he had gone; but when he re-

turned a week later he said he had gone to Maiduguri in Nigeria to see

an old friend of his. Two days later when the mailvan arrived Nkien-

dah received the letter from Thomas Wanti, the Oku man working in

the Divisional Office, Kumba. There was ten thousand francs en-

closed. In it this Thomas Wanti claimed that a few years back while he

was on tour of the Noni clan in the entourage of the Provincial Ad-

ministrator he had noticed and immediately admired young Yiwsi. He

had made inquiries very quietly and had been told that she was the

daughter of Nkiendah. If she was not yet married, as he sincerely

hoped was the case, he would make her his wife without any delay.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

85

There was also a photograph of himself enclosed. It was a full length

picture and he was wearing a beautifully cut dark suit and dark

glasses. Thomas Wanti said he had heard about the exceptional char-

acter and behaviour of Yiwsi. That was why he was determined to

make her his first and only wife.

When he had heard the contents of the letter Nkiendah had immedi-

ately realised that a child would constitute a hindrance to this very

promising match. He remembered that five years back the Provincial

Administrator had indeed visited the Noni clan with a large group of

people. So many vehicles had never been seen in any of the Noni vil-

lages on any one occasion. This Thomas Wanti was in that group,

then?

Nkiendah removed the picture from his danshiki pocket and handed

it over to Pa Toma.

"That is the man. When I showed that photo at the big office up

there, they said they had never seen such a man in the place," he said

with a shaky voice.

"Did you show it to the Oku people?" Pa Toma asked, examining it

closely.

"I did. But in the whole of that meeting nobody recognised the per-

son.

"And you say he sent money, too?"

"Yes, there was ten thousand francs in the letter. He said if the

money was not enough I shouldn't fear to borrow more."

Pa Toma could not understand how a man could simply receive a

letter with money and a photo in it and immediately pack up his

daughter and things and set out on a journey of nearly four hundred

kilometres without enough money in his pocket. He knew, of course,

that back in the villages the practice of marriage proposals by photos

was a very common phenomenon. But the family of the man was al-

ways well-known to everyone in the village. How Nkiendah could

have set out for Kumba without even bothering to investigate in

Njikijem, which was at most two days journey away from his own vil-

lage, was incomprehensible. But Pa Toma did not know about Nkien-

dah's red eyes. He did not know about his lust for money. He did not

know that Nkiendah had eaten Sama Ndifon's money and refused to

give him the bride. He did not know that Nkiendah had even im-

pounded Ndifon's only son, Ntumfon, until he realised that the off-

spring was standing in the way of his making more money. That is

why he had hurriedly called Sama Ndifon that same night of the fate-

ful letter and asked him to take away his son.

"I can't sleep at night," he had said. "Nobody sleeps in this com-

pound. I know you are bewitching us because of your son. Take him

away and give us peace and sleep."

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

86

And Ndifon had quietly taken away his son and disappeared from

the village the very next day.

Pa Toma did not know any of these things. He didn't want to ask

the several questions that were worrying him. What was the use mak-

ing Nkiendah's grief even more bitter? So he left the several questions

unasked and instead said: "I have called an emergency meeting of the

Noni people tomorrow. We must find a way out and send you and

your daughter back to the village. The meeting is there to help in cases

such as yours. That is why we have always said that it is good to live

together and to have a good word for everyone. We insist on that. If

you people have your family and village quarrels back at home, those

of us who are out here are all brothers and sisters. Because we know

that no man can live by himself no matter how wealthy or intelligent

he is. Rest your mind. I know our people will give you money to go

back home. The elders say that one hand washes the other. It is the

principle on which we live here in Kumba. I don't know how you peo-

ple live at home, but I am sure that this thing that has happened to you

is not for nothing. It is pregnant. When you go back home call the

man with whom you have a quarrel and settle the matter. Our people

say that you void your bowels in the same measure as you eat. Go

back to the village and have this affair solved before the thing deliv-

ers. My own is finished."

Copyright?1979by BoleButake

All rightsreserved.

Reprintedwith permissionfrom TheMould, No. 3, 1979.

Universityof Yaounde.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.76 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Solutions To SHL Online Practice Test OnDocument7 pagesSolutions To SHL Online Practice Test OnGanesh Un100% (2)

- Statistics and Probability: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Normal DistributionDocument45 pagesStatistics and Probability: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Normal DistributionRegie Carino100% (1)

- THE ONE-HANDED GIRL - A Swahili Children's Story: Baba Indaba’s Children's Stories - Issue 404From EverandTHE ONE-HANDED GIRL - A Swahili Children's Story: Baba Indaba’s Children's Stories - Issue 404No ratings yet

- Bobcat Telehandler t3571-t3571lDocument408 pagesBobcat Telehandler t3571-t3571lHai Van100% (6)

- Esade-Recommendation Letter MBA FTDocument2 pagesEsade-Recommendation Letter MBA FTSabeer KasthuriNo ratings yet

- Stories of Juan TamadDocument5 pagesStories of Juan Tamadaintenough80% (5)

- Different Adventures of Juan TamadDocument8 pagesDifferent Adventures of Juan TamadMs. 37o?sA40% (5)

- The Madhouse (TJ Benson) (Z-Library)Document256 pagesThe Madhouse (TJ Benson) (Z-Library)sharonoluwanifemi29No ratings yet

- AsdasdDocument2 pagesAsdasdMonin SterjaNo ratings yet

- Two Brothers Who Were FriendsDocument2 pagesTwo Brothers Who Were Friendsoneng simanjuntakNo ratings yet

- His Banner over Me Is Love: The Dreams of an African WomanFrom EverandHis Banner over Me Is Love: The Dreams of an African WomanNo ratings yet

- The Tale of The Two BrothersDocument5 pagesThe Tale of The Two BrothersRich Lee RoyalNo ratings yet

- Fathers, SonsDocument37 pagesFathers, SonsGRK MurtyNo ratings yet

- Cloze 1Document6 pagesCloze 1Kim AnhNo ratings yet

- Philippine Representative Texts and AuthorsDocument9 pagesPhilippine Representative Texts and Authorsarlynhamchawan131No ratings yet

- Famous Tales from the Chagga Tribe of Kilimanjaro-Tanzania: Famous Chagga StoriesFrom EverandFamous Tales from the Chagga Tribe of Kilimanjaro-Tanzania: Famous Chagga StoriesNo ratings yet

- Download ebook pdf of The Uk In The Modern World People In Politics Учебно Методическое Пособие 1St Edition Жерновая О. Р. full chapterDocument25 pagesDownload ebook pdf of The Uk In The Modern World People In Politics Учебно Методическое Пособие 1St Edition Жерновая О. Р. full chapterallenabirand100% (9)

- The Tax CollectorDocument11 pagesThe Tax Collectorapi-3850255100% (1)

- The Hospital WindowDocument9 pagesThe Hospital WindowMah Soon WengNo ratings yet

- The BogeyDocument3 pagesThe BogeyMónicaNo ratings yet

- The Boy Who Was Called Thick-HeadDocument2 pagesThe Boy Who Was Called Thick-Headmaria yvonne camilotesNo ratings yet

- HCI Exam ReviewDocument21 pagesHCI Exam ReviewSarah O'ConnorNo ratings yet

- Inomax ACS580 VFD User Manual V220Document112 pagesInomax ACS580 VFD User Manual V220luis castiblanco100% (1)

- 8609 Smart Router Modular-Access-RouterDocument3 pages8609 Smart Router Modular-Access-RouterGisselle GranadaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Data AnalysisDocument16 pagesChapter 4: Data AnalysissanuNo ratings yet

- How To Make The Home Wiring Board or Extension BoxDocument3 pagesHow To Make The Home Wiring Board or Extension Box2711323No ratings yet

- Smart Grid System Operation (ELEN-6108) Lec 5Document14 pagesSmart Grid System Operation (ELEN-6108) Lec 5musaNo ratings yet

- IT Strategy + Case Analysis Module Introduction: Professor Tony GerthDocument10 pagesIT Strategy + Case Analysis Module Introduction: Professor Tony GerthVarun DagaNo ratings yet

- Solidworks ExerciseDocument13 pagesSolidworks Exerciseاسامه عبد اللهNo ratings yet

- En Tor-3Document71 pagesEn Tor-3Multitech InternationalNo ratings yet

- Assignment - PLCs & Control SystemsDocument6 pagesAssignment - PLCs & Control SystemsSaud Ahmed NizamiNo ratings yet

- Operations AnalyticsDocument4 pagesOperations AnalyticsAkshatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 07 - BennettDocument147 pagesChapter 07 - Bennettuet taxilaNo ratings yet

- How To Develop A Software From Scratch by MAPHIL NEHRSDocument4 pagesHow To Develop A Software From Scratch by MAPHIL NEHRSomojugbaaduraNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Sudzarama Software Development 1Document14 pagesRunning Head: Sudzarama Software Development 1Isaac Hassan0% (1)

- Self-Lift DC-DC Converters: M Ail IlDocument6 pagesSelf-Lift DC-DC Converters: M Ail IlStudents Xerox ChidambaramNo ratings yet

- Well CompletionDocument22 pagesWell CompletionRobot100% (1)

- Wellington WT9179 - I7 03-21 ECR2 DatasheetDocument2 pagesWellington WT9179 - I7 03-21 ECR2 DatasheetHans Pico BarriosNo ratings yet

- Rezultat Testova Napisanih U Kodu I Ispis Logova Koda Servisa Za Iste 240223Document14 pagesRezultat Testova Napisanih U Kodu I Ispis Logova Koda Servisa Za Iste 240223mahirdzirloNo ratings yet

- Big Blue 500X PRO 2021Document8 pagesBig Blue 500X PRO 2021Seida Rojas CabelloNo ratings yet

- Material Consumption: S.NO. Items QTY Unit Cement Sand Metal Steel Shutring 40 MM 20 MMDocument15 pagesMaterial Consumption: S.NO. Items QTY Unit Cement Sand Metal Steel Shutring 40 MM 20 MMUpendra kumarNo ratings yet

- Installation Manual: EM 710 Multibeam Echo SounderDocument155 pagesInstallation Manual: EM 710 Multibeam Echo SounderEvelyn HerediaNo ratings yet

- Volume 19 Issue 3: International Journal of Virtual RealityDocument16 pagesVolume 19 Issue 3: International Journal of Virtual RealityMARYAMNo ratings yet

- Optical Communication Systems: Introduce An Overview of Optical Systems and Actual WorksDocument39 pagesOptical Communication Systems: Introduce An Overview of Optical Systems and Actual Workstien nguyenNo ratings yet

- OOSD Design Case StudiesDocument10 pagesOOSD Design Case StudiesmarioNo ratings yet

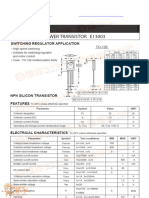

- Power Transistor E13003: Switching Regulator ApplicationDocument2 pagesPower Transistor E13003: Switching Regulator Applicationblancodaniel00000No ratings yet

- NTC Building Report Revised - SudishDocument19 pagesNTC Building Report Revised - SudishSudipThapaNo ratings yet