Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Is Insecure Parent - Child Attachment A Risk Factor For The Development of Anxiety in Childhood or Adolescence?

Uploaded by

Susan KuriakoseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Is Insecure Parent - Child Attachment A Risk Factor For The Development of Anxiety in Childhood or Adolescence?

Uploaded by

Susan KuriakoseCopyright:

Available Formats

CHILD DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVES

Is Insecure Parent–Child Attachment a Risk Factor for

the Development of Anxiety in Childhood or

Adolescence?

Kathryn A. Kerns1 and Laura E. Brumariu2

1

Kent State University and 2Adelphi University

ABSTRACT—In this article, we address how and why par- safe haven during times of distress and as a secure base from

ent–child attachment is related to anxiety in children. which to explore the environment when not distressed. Although

Children who do not form secure attachments to caregiv- all children are expected to form attachments (except in cases of

ers risk developing anxiety or other internalizing prob- extreme deprivation), the quality (specifically, security) of attach-

lems. While meta-analyses yield different findings ments varies substantially. A child who is securely attached is

regarding which insecurely attached children are at great- able to use his or her parent as a safe haven and a secure base,

est risk, our recent studies suggest that disorganized chil- and develops cognitive models of the self as loveable and of care-

dren may be most at risk. Insecure attachment itself may givers as responsive, sensitive, and available (Bowlby, 1973).

contribute to anxiety, but insecurely attached children Although attachments emerge in the 1st year of life, they are

also are more likely to have difficulties regulating emo- important for healthy development across the life span (Ains-

tions and interacting competently with peers, which may worth, 1989), and parents continue to function as primary attach-

further contribute to anxiety. Clinical disorders occur pri- ment figures for children at least through preadolescence (Seibert

marily when insecure attachment combines with other risk & Kerns, 2009) and possibly across the adolescent years.

factors. In this article, we present a model of factors A major tenet of attachment theory is the competence hypoth-

related to developing anxiety. esis, which posits that the formation of a secure attachment in

childhood prepares a child for other social challenges (e.g., find-

KEYWORDS—attachment; anxiety

ing a place in the peer group) and places a child on a more

positive developmental trajectory (Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, &

Parent–child relationships influence children’s social and emo- Carlson, 2008). Several mechanisms may account for this effect

tional development (Maccoby, 2007). An example is research on (Contreras & Kerns, 2000; Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 1999);

parent–child attachment. In the 1st year of life, all children form for example, through daily interactions with sensitive caregivers,

attachments to caregivers who provide them protection and care securely attached children may have more opportunities to learn

(Bowlby, 1982) and children organize their behavior to use a competent social interaction and emotion regulation skills. In

parent as a secure base (Ainsworth, 1989). The secure base addition, securely attached children may develop more positive

phenomenon occurs when a child uses his or her parent as a expectations about others and a greater sense of self-efficacy,

which in turn facilitate their social relationships. Consistent with

Kathryn A. Kerns, Department of Psychology, Kent State Univer- the competence hypothesis, children who are more securely

sity; Laura E. Brumariu, Derner Institute of Psychology, Adelphi attached form more positive relationships with peers, cooperate

University.

more with adults, and regulate their emotions more effectively

This work was supported by grants from the Kent State University (Kerns, 2008; Thompson, 2008; Weinfield et al., 2008).

Research Council and NICHD (Early Child Care Study).

More recently, researchers have asked how and why attach-

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to ment contributes to the development of psychopathology. Bowl-

Kathryn A. Kerns, Department of Psychology, Kent State Univer-

sity, Kent, OH 44242; e-mail: kkerns@kent.edu. by (1982) originally focused on attachment because his clinical

work identified parent–child relationships as influencing the

© 2013 The Authors

Child Development Perspectives © 2013 The Society for Research in Child Development

development of troubled behavior in childhood; subsequently,

DOI: 10.1111/cdep.12054 scientists have sought to understand how insecure attachments

Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

Attachment and Internalizing Problems 13

may contribute to developing externalizing behaviors (e.g., Common to all insecurely attached children is the inability to

aggression, delinquency) and internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxi- use one’s parent as a secure base and safe haven, and negative

ety, depression). Our work focuses on whether parent–child beliefs about the availability and accessibility of caregivers, but

attachment is a risk factor for developing anxiety or depression insecurity is manifested in different ways (Cassidy, 1994; Main,

in childhood and adolescence, and addresses three interrelated Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Children with avoidant attachments

questions, which we illustrate by discussing our work on attach- can be overly self-reliant and maintain emotional distance from

ment and anxiety: (a) Is attachment related to anxiety and if so, a rejecting caregiver; children with ambivalent (or preoccupied)

is lack of secure attachment or specific forms of insecure attach- attachments are chronically unsure of the caregiver’s availabil-

ment more strongly related to anxiety? (b) What accounts for ity, which can lead them to be vigilant about remaining in close

why attachment is related to anxiety—is it lack of a secure base contact with caregivers; and children with disorganized attach-

per se that contributes to anxious feelings, or do other factors ments, who have experienced caregivers who are harsh, psycho-

(e.g., child competencies) mediate or explain the link between logically unavailable, or unpredictable, may either lack a

attachment and anxiety? (c) Is attachment related to anxiety, coherent strategy for relating to the parent or take control of the

when considering other known influences on anxiety such as relationship through role reversal (e.g., taking care of the

parenting or temperament, and does it interact with other risk parent).

factors to magnify risk? The work we describe focuses on global Insecure ambivalent children may be most prone to experi-

measures of anxiety rather than specific forms of anxiety. ence anxiety because they are chronically worried about the

availability of attachment figures (Carlson & Sroufe, 1995).

IS PARENT–CHILD ATTACHMENT RELATED TO Alternatively, some researchers (e.g., Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a;

ANXIETY? Moss, Rousseau, Parent, St. Laurent, & Saintonage, 1998; Moss

et al., 2006) suggest that disorganized children, who perceive

Bowlby (1973) suggested that children experience anxiety when themselves as helpless and vulnerable, and caregivers as fright-

they have doubts about the availability or accessibility of ening and unable to protect them, may be at greatest risk for

attachment figures, especially when they experience difficult or developing internalizing problems, including anxiety. Finally,

disturbing events. Conversely, access to a caregiver who pro- ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized attachment may predis-

vides a secure base and safe haven should mitigate anxious pose children to develop different types of anxiety (Manassis,

feelings. Over time, repeated experiences with attachment 2001). For example, ambivalent children may be most prone to

figures lead children to develop general expectations about the experience separation anxiety, avoidant children may be most

availability and accessibility of those attachment figures, which prone to social phobia, and disorganized children may be prone

can lead to chronic anxiety if children come to believe that to school phobia.

attachment figures are not consistently available, protective, and The four reviews differ in their conclusions about which spe-

comforting. cific types of insecure attachment are associated with greater

Several reviews have addressed whether insecure attachment risk for anxiety or internalizing problems. One reported that only

is related to anxiety or, more generally, internalizing disorders. avoidant attachment was related to internalizing problems, most

Two meta-analyses of parent–child attachment and internalizing strongly to social withdrawal (Groh et al., 2012). One found that

problems (Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakersman-Kranen- both avoidant and disorganized attachment were associated with

burg, & Fearon, 2012; Madigan, Atkinson, Laurin, & Benoit, internalizing problems, although the latter was not significant

2013) included only studies that used observational measures to after controlling for publication bias (Madigan et al., 2013).

assess attachment in early childhood. One narrative review (Bru- One examined only one insecure pattern—ambivalence—and

mariu & Kerns, 2010a) examined evidence for associations of concluded that children with ambivalent attachments are

parent–child attachment with anxiety, depression, or internaliz- more prone to experiencing anxiety (Colonnesi et al., 2011).

ing problems in childhood or adolescence, and included studies In our narrative review (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a)—which

that used a diverse range of attachment measures (i.e., behavioral examined avoidance, ambivalence, and disorganization, as well

observation, representational measures, and questionnaires). as security—we noted that firm conclusions were difficult to

Another meta-analysis (Colonnesi et al., 2011) examined the draw, especially when considering the use of different attach-

association between attachment and anxiety in childhood and ment measures and different ages. Nevertheless, we suggested

adolescence, including studies that assessed either parent–child disorganized attachment may be the insecure attachment pattern

or child–peer attachment, using any type of attachment measure. most consistently related to internalizing problems.

All four of these reviews concluded that insecure attachment The reviews differed substantially in terms of the studies they

(compared to secure attachment) is associated with higher levels considered. The Groh et al. (2012) and Madigan et al. (2013)

of anxiety or internalizing problems. meta-analyses included only studies that used observational

In contrast, researchers disagree about whether specific forms measures of attachment (which are used with young children),

of insecure attachment place children at greater risk for anxiety. and in these studies internalizing problems were usually

Child Development Perspectives, Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

14 Kathryn A. Kerns and Laura E. Brumariu

assessed in early or middle childhood. Thus, these meta-analy- disorder. Thus, despite differences across the studies in how

ses address the question of whether early attachment forecasts attachment and anxiety were assessed, all three showed that

early childhood internalizing problems, and do not evaluate disorganized attachment was associated with greater anxiety. As

whether attachment is relevant for developing internalizing more studies are done of insecure attachment and anxiety at

problems later. Depression and many types of anxiety occur older ages, we predict that disorganized children, who lack

more frequently in adolescence than earlier, so studies with access to a secure base, will be most at risk for developing

younger children miss the period during which some internaliz- anxiety.

ing problems occur.1 Colonnesi et al. (2011) included studies

that assessed attachment across childhood and adolescence, and WHY IS ATTACHMENT RELATED TO ANXIETY?

found that the association between attachment and anxiety was

stronger in adolescence than in childhood and in studies that While insecurely attached children are apparently at risk for

used questionnaires rather than other types of attachment mea- developing anxiety, the reason is less clear. Lack of a secure

sures. The limited pool of available studies that assessed spe- base may lead directly to feelings of anxiety (Bowlby, 1973).

cific insecure attachment patterns constrains all the reviews, However, according to the competence hypothesis, children who

especially when looking at specific types of internalizing prob- are insecurely attached also are less socially and emotionally

lems or specific age groups. For example, Groh et al. (2012) competent, which in turn may contribute to the development of

identified only two studies that examined disorganization and anxiety. Thus, insecurely attached children may be anxious not

clinical depression, and even though they had a strong associa- only because they lack a secure base but because they are

tion, this finding was not interpreted due to the small sample prone to having other experiences (e.g., difficulties with peers)

size. Although Colonnesi et al. found that ambivalent attach- that contribute to anxiety.

ment was related to child anxiety, they did not examine disorga- We have speculated whether emotion regulation and peer

nized attachment in their analyses; in our review (Brumariu & competence partially explain associations between attachment

Kerns, 2010a), although ambivalent attachment was related to and anxiety. We have focused on these two potential mecha-

anxiety in some studies, this was not the case for those studies nisms because theoretical reasons suggest that each is related to

that included children with disorganized attachments as a attachment and anxiety. Emotion regulation is integral to attach-

separate group. ment in that children use the attachment figure as a resource to

To shed further light on the question of which insecure attach- regulate their own emotions (e.g., seeking comfort). Children

ment pattern is most related to anxiety and to address gaps in also learn about emotions, emotion communication, and regulat-

the literature, we conducted a series of studies to examine how ing emotion in the context of interactions with attachment

attachment is related to anxiety in preadolescence or adoles- figures (Cassidy, 1994; Contreras & Kerns, 2000). Securely

cence (Brumariu, Kerns, & Seibert, 2012). We examined con- attached children manage emotions better, even in the absence

current associations between a story stem measure of of the caregiver (e.g., Abraham & Kerns, in press; Kerns,

attachment and self-reports of anxiety symptoms in 10- to 12- Abraham, Schlegelmilch, & Morgan, 2007; Sroufe, Egeland, &

year-olds. Children who were less secure or more disorganized Kreutzer, 1990). In addition, emotion regulation processes are

were more anxious; in contrast, ambivalence and avoidance related to anxiety. By definition, anxiety reflects difficulties

were not related to anxiety. In a different sample (Brumariu & managing emotional arousal and the intense experience of nega-

Kerns, 2013), we used observational measures of attachment tive emotions. Anxious children regulate their emotions, but the

from the first 3 years to predict maternal reports of children’s processes involved in regulating emotion tend to be ineffective

anxiety symptoms at ages 10 to 12. Again, both security and dis- (Thompson, 2001). For example, anxious children have difficulty

organization were related to later anxiety, but ambivalence and identifying their own emotions, are prone to negatively evaluate

avoidance were not. In a third study (Brumariu, Obsuth, & emotionally laden situations, and use less adaptive coping strat-

Lyons-Ruth, 2013) of older adolescents, disorganized attachment egies (Brumariu et al., 2012; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2002).

was assessed with both the Adult Attachment Interview and an We propose that processes of emotion regulation may help

observational measure of parent–child interaction, and anxiety explain why insecurely attached children are more anxious (Bru-

disorders were assessed with a clinical interview. Adolescents mariu & Kerns, 2010a; see Esbjorn, Bender, Reinholdt-Dunne,

with anxiety disorders had more disorganized representations Munck, & Ollendick, 2012, for a similar perspective). In a

and interaction patterns than adolescents without a clinical cross-sectional study of 10- to 12-year-old children (Brumariu

et al., 2012), children’s greater awareness of emotions helped

1 explain why securely attached children were less anxious, and

A reviewer asked why avoidant attachment was related to internalizing prob-

lems in two of the meta-analyses. Measures of internalizing symptoms in young the tendency to catastrophize in upsetting situations helped

children will capture only those symptoms seen at that age (e.g., social withdrawal explain why disorganized children were more anxious. Moreover,

but not depression). Avoidant attachment was related most strongly in Groh et al.

(2012) to social withdrawal, which we speculate may reflect the fact that avoidant- in two longitudinal studies (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Brumariu

ly attached children have difficulties in peer interactions at young ages. & Kerns, 2013), children who were securely attached early in

Child Development Perspectives, Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

Attachment and Internalizing Problems 15

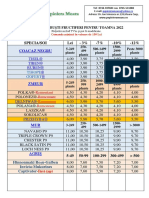

Parental anxiety

Attachment

insecurity

Peer

relationships

Child

Emotion anxiety

regulation

difficulties

Parenting Biological factors

(e.g., control, (temperament,

acceptance) genetics) Life stress

Figure 1. Simplified conceptual model of factors related to the development of anxiety.

life were less anxious in late childhood, in part because they 2010), insecure attachment may lead to anxiety or other inter-

managed their emotions better. nalizing problems in part because insecurely attached children

Relationships with peers also may contribute to insecurely have difficulties regulating emotions and getting along with

attached children’s anxiety. Securely attached children are more peers, experiences that in turn further heighten children’s risk

cooperative, better liked by peers, and form more supportive for developing anxiety.

friendships than insecurely attached children (Booth-LaForce & Anxiety also has been linked to several risk factors other than

Kerns, 2009; Schneider, Atkinson, & Tardif, 2001). Peer rela- attachment, including temperament (e.g., behavioral inhibition,

tionships are also related to anxiety in that more anxious chil- negative emotion), stressful life events, and parenting (e.g.,

dren perceive themselves to be less competent with peers, are acceptance, control). All these factors are related to anxiety,

more likely to be victimized by peers, and have more difficulties independent of attachment (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010b, 2013;

in friendships and romantic relationships (Brumariu et al., Kerns et al., 2011). Thus, while attachment is an important part

2013; Kingery, Erdley, Marshall, Whitaker, & Reuter, 2010). of understanding why some children develop anxiety, it is only

Consistent with the idea that peer relationships play a role in part of the explanation. Risk factors such as temperament, spe-

explaining associations between attachment and anxiety, in two cific genes, or maternal anxiety may accentuate or moderate the

studies, children securely attached in the first 3 years were impact of attachment. For example, insecurely attached chil-

more competent with peers in middle childhood, which in turn dren had frequent symptoms of social phobia regardless of their

accounted for why they experienced less anxiety in late child- levels of behavioral inhibition, whereas securely attached chil-

hood or adolescence (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Brumariu & dren had frequent symptoms of social phobia only if they were

Kerns, 2013). also inhibited (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010b). Finally, although

parent–child relationships can influence later social competen-

PLACING ATTACHMENT IN A BROADER CONTEXT cies and anxiety, reciprocal effects exist across time, as shown

in the figure. For example, as children become more anxious,

Failure to form a secure attachment to a caregiver in childhood they may have increasing difficulty regulating emotions and

places children at risk for developing anxiety. However, the their parents may respond to their anxiety in ways that lead

magnitude of the association is modest, and single risk factors, children to feel less secure (e.g., parents may be more rejecting

in isolation, rarely lead to the development of a clinical disorder. or controlling).

Consistent with a developmental psychopathology perspective

(Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000), multiple risk factors contribute to CONCLUSIONS

the development of anxiety (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010a; Kerns,

Siener, & Brumariu, 2011). A number of potential pathways and Insecure parent–child attachment is one risk factor for the

moderating factors link family relationships, child characteris- development of anxiety. Our recent studies also show that disor-

tics, and child anxiety (see Figure 1, a simplified model that ganized attachment is associated with anxiety. Attachment may

draws on an earlier conceptual model [Brumariu & Kerns, be associated with anxiety, in part, because insecurely attached

2010a] and is an example of a broader model that considers the children are less likely to develop competent emotion regulation

role of attachment in the development of anxiety). For example, and social interaction skills, which in turn places them at risk

as described previously and consistent with cascade models of for experiences that contribute to the development of anxiety.

the development of psychopathology (Masten & Cicchetti, Researchers should further test factors that may explain why

Child Development Perspectives, Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

16 Kathryn A. Kerns and Laura E. Brumariu

attachment and anxiety are related, as well as broader models of cure attachment and child anxiety: A meta-analytic study. Journal

how different risk factors interact over time to explain why some of Child Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 630–645. doi:

children develop anxiety disorders. 10.1080/15374416.2011.581623

Contreras, J. M., & Kerns, K. A. (2000). Emotion regulation processes:

Explaining links between parent–child attachment and peer rela-

REFERENCES tionships. In K. A. Kerns, J. M. Contreras, & A. M. Neal-Barnett

(Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds (pp. 1–25).

Abraham, M. M., & Kerns, K. A. (in press). Positive and negative emo- Westport, CT: Praeger.

tions and coping as mediators of the link between mother-child Esbjorn, B. H., Bender, P. K., Reinholdt-Dunne, M. L., Munck, L. A., &

attachment and peer relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. Ollendick, T. H. (2012). The development of anxiety disorders:

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psy- The contributions of attachment and emotion regulation. Clinical

chologist, 44, 709–716. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709 Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 129–143. doi:10.1007/

Booth-LaForce, C., & Kerns, K. A. (2009). Child-parent attachment rela- s10567-011-0105-4

tionships, peer relationships, and peer group functioning. In K. H. Groh, A. M., Roisman, G. I., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakersman-Kranen-

Rubin, W. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer inter- burg, M. J., & Fearon, R. P. (2012). The significance of insecure

actions, peer relationships, and peer group functioning (pp. 490– and disorganized attachment for children’s internalizing symptoms:

507). New York, NY: Guilford. A meta-analytic study. Child Development, 83, 591–610. doi:

Bosquet, M., & Egeland, B. (2006). The development and maintenance 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01711.x

of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitu- Kerns, K. A. (2008). Attachment in middle childhood. In J. Cassidy &

dinal sample. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 517–550. P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (2nd ed., pp. 366–382).

doi:10.1017/S0954579406060275 New York, NY: Guilford.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. New York, Kerns, K. A., Abraham, M. M., Schlegelmilch, A., & Morgan, T. A.

NY: Basic Books. (2007). Mother-child attachment in later middle childhood: Assess-

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). ment approaches and associations with mood and emotion regula-

New York, NY: Basic Books. tion. Attachment and Human Development, 9, 33–53. doi:10.1080/

Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2010a). Parent–child attachment and 14616730601151441

internalizing symptomatology in childhood and adolescence: A Kerns, K. A., Siener, S., & Brumariu, L. E. (2011). Mother-child rela-

review of empirical findings and future directions. Development tionships, family context, and child characteristics as predictors of

and Psychopathology, 22, 177–203. doi:10.1017/S09545794 anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Development and Psycho-

09990344 pathology, 23, 593–604. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000228

Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2010b). Mother-child attachment pat- Kingery, J. N., Erdley, C. A., Marshall, K. C., Whitaker, K. G., &

terns and different types of anxiety symptoms: Is there specificity Reuter, T. R. (2010). Peer experiences of anxious and socially

of relations? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 663– withdrawn youth: An integrative review of the developmental and

674. doi:10.1007/s10578-010-0195-0 clinical literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review,

Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2013). Pathways to anxiety: Contribu- 13, 91–128. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0063-2

tions of attachment history, temperament, peer competence, and Maccoby, E. E. (2007). Historical overview of socialization research and

ability to manage intense emotions. Child Psychiatry and Human theory. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of social-

Development, 44, 504–515. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0345-7 ization (pp. 1–41). New York, NY: Guilford.

Brumariu, L. E., Kerns, K. A., & Seibert, A. C. (2012). Mother-child Madigan, S., Atkinson, L., Laurin, K., & Benoit, D. (2013). Attachment

attachment, emotion regulation, and anxiety symptoms in middle and internalizing behavior in childhood: A meta-analysis. Develop-

childhood. Personal Relationships, 19, 569–585. doi:10.1111/j. mental Psychology, 49, 672–689. doi:10.1037/a0028793

1475-6811.2011.01379.x Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security of infancy, child-

Brumariu, L. E., Obsuth, I., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2013). Quality of attach- hood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I.

ment relationships and peer relationship dysfunction among late Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Monographs of the Society for

adolescents with and without anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Research in Child Development, 50(Serial No. 209), 66–104.

Disorders, 27, 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.002 Manassis, K. (2001). Child-parent relations: Attachment and anxiety

Carlson, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1995). Contribution of attachment theory disorders. In W. K. Silverman & P. D. A. Treffers (Eds.), Anxiety

to developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen disorders in children and adolescents: Research, assessment, and

(Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and methods intervention (pp. 255–272). Cambridge, England: Cambridge Uni-

(pp. 581–616). Oxford, England: Wiley. versity Press.

Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment rela- Masten, A. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Develop-

tionships. In N. A. Fox (Ed.), The development of emotion regula- ment and Psychopathology, 22, 491–495. doi:10.1017/S09545794

tion: Biological and behavioral considerations. Monographs of the 10000222

Society for Research in Child Development, 59(Serial No. 240), Moss, E., Rousseau, D., Parent, S., St. Laurent, D., & Saintonage, J.

228–249. (1998). Correlates of attachment at school age: Maternal reported

Cicchetti, D., & Sroufe, A. (2000). The past as prologue to the future: stress, mother-child interaction, and behavior problems. Child

The times, they’ve been a-changin’. Development and Psychopathol- Development, 69, 1390–1405. doi:10.2307/1132273

ogy, 12, 255–264. doi:10.1017/S0954579400003011 Moss, E., Smolla, N., Cyr, C., Dubois-Comtois, K., Mazzarello, T., &

Colonnesi, C., Draijer, E. M., Stams, G. J. J. M., van der Bruggem, C. Berthiaume, C. (2006). Attachment and behavior problems in

O., Bogels, S. M., & Noom, M. J. (2011). The relation between inse- middle childhood as reported by adult and child informants.

Child Development Perspectives, Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

Attachment and Internalizing Problems 17

Development and Psychopathology, 18, 425–444. doi:10.1017/ Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Kreutzer, T. (1990). The fate of early expe-

S0954579406060238 rience following developmental change: Longitudinal approaches

Schneider, B. H., Atkinson, L., & Tardif, C. (2001). Child-parent to individual adaptation in childhood. Child Development, 61,

attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. 1363–1373. doi:10.2307/1130748

Developmental Psychology, 37, 86–100. doi:10.1037/0012-1649. Thompson, R. A. (2001). Childhood anxiety disorders from the perspec-

37.1.86 tive of emotion regulation and attachment. In M. W. Vasey & M.

Seibert, A. C., & Kerns, K. A. (2009). Attachment figures in middle R. Dadds (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp.

childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 160–182). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

347–355. doi:10.1177/0165025409103872 Thompson, R. A. (2008). Early attachment and later development:

Southam-Gerow, M. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2002). Emotion regulation and Familiar questions, new answers. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver

understanding: Implications for child psychopathology and therapy. (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (2nd ed., pp. 348–365). New York,

Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 189–222. doi:10.1016/S0272- NY: Guilford.

7358(01)00087-3 Weinfield, N. S., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. (2008). Indi-

Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. A. (1999). One social world: vidual differences in infant-caregiver attachment: Conceptual and

The integrated development of parent–child and peer relationships. empirical aspects of security. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.),

In W. A. Collins & B. Laursen (Eds.), Relationships as developmen- Handbook of attachment (2nd ed., pp. 78–101). New York, NY:

tal contexts (pp. 241–261). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Guilford.

Child Development Perspectives, Volume 8, Number 1, 2014, Pages 12–17

You might also like

- Attachment and Trauma in Early ChildhoodDocument18 pagesAttachment and Trauma in Early ChildhoodAnonymous KrfJpXb4iNNo ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument80 pagesAttachmentanantheshkNo ratings yet

- PSYCH101 Wiki Attachment TheoryDocument25 pagesPSYCH101 Wiki Attachment TheoryMadalina-Adriana ChihaiaNo ratings yet

- Wilson, D.S., Hayes, S.C. & Biglan, A. (2018). Evolution and contextual behavioral science an integrated framework for understanding, predicting and influencing human behavior. Oakland Context Press..pdfDocument390 pagesWilson, D.S., Hayes, S.C. & Biglan, A. (2018). Evolution and contextual behavioral science an integrated framework for understanding, predicting and influencing human behavior. Oakland Context Press..pdfjesus100% (3)

- Theory of LoveDocument6 pagesTheory of LoveShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- MLTG Competency ProfileDocument18 pagesMLTG Competency ProfileJessie TNo ratings yet

- Attachement Parentyng Styles PDFDocument6 pagesAttachement Parentyng Styles PDFOvidiu BerarNo ratings yet

- Primal Healing - Access The Incredible Power of Feelings To Improve Your Health (PDFDrive)Document510 pagesPrimal Healing - Access The Incredible Power of Feelings To Improve Your Health (PDFDrive)Adriana Rosa100% (2)

- Infant Child CareDocument4 pagesInfant Child CareRichson BacayNo ratings yet

- MC Science - Revision WS - Stage 5 - C03Document9 pagesMC Science - Revision WS - Stage 5 - C03Camille HugoNo ratings yet

- Attachment DisordersDocument9 pagesAttachment DisordersALNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- Project Report On Turmeric Processing (Turmeric Powder, Curcumin and Turmeric Oil)Document8 pagesProject Report On Turmeric Processing (Turmeric Powder, Curcumin and Turmeric Oil)EIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNo ratings yet

- Collins & Feeney, 2013Document6 pagesCollins & Feeney, 2013Romina Adaos OrregoNo ratings yet

- Breidenstine 2011 Attachment Trauma EarlyChildhoodDocument17 pagesBreidenstine 2011 Attachment Trauma EarlyChildhoodAmalia PagratiNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and FathersDocument16 pagesAttachment Theory and FathersGraceNo ratings yet

- Effects of Attachment On Early and Later Development: Mokhtar MalekpourDocument15 pagesEffects of Attachment On Early and Later Development: Mokhtar MalekpourJuan Baldana100% (1)

- The Key Person Approach: Positive Relationships in the Early YearsFrom EverandThe Key Person Approach: Positive Relationships in the Early YearsNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010Document11 pagesAttachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010LisaDarlingNo ratings yet

- Mother-Child Relationships, Family Context, and Child Characteristics As Predictors of Anxiety Symptoms in Middle ChildhoodDocument13 pagesMother-Child Relationships, Family Context, and Child Characteristics As Predictors of Anxiety Symptoms in Middle ChildhoodNina GarfoNo ratings yet

- Vinculação ParentalDocument23 pagesVinculação ParentalNeiler OverpowerNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022096522001631 Main 2Document15 pages1 s2.0 S0022096522001631 Main 2Danial S. SaktiNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 01064 v3Document22 pagesIjerph 19 01064 v3Camila Sofía Díaz OyarzúnNo ratings yet

- Family Issues in Child Anxiety AttachmenDocument23 pagesFamily Issues in Child Anxiety AttachmenPaula PopaNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Preschool Teacher. An Opportunity To Develop A Secure BaseDocument16 pagesAttachment and Preschool Teacher. An Opportunity To Develop A Secure BaseRoxana MedinaNo ratings yet

- Disorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeDocument25 pagesDisorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeGabe MartindaleNo ratings yet

- Erickson 1985Document21 pagesErickson 1985Annisa IkhwanusNo ratings yet

- Kerns Et Al 2001 PDFDocument13 pagesKerns Et Al 2001 PDFAndreia MartinsNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Enhancing Attachment Organization Among Maltreated Children: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument20 pagesNIH Public Access: Enhancing Attachment Organization Among Maltreated Children: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialPyaePhyoAungNo ratings yet

- Q-Sort Assessment of Attachment SecurityDocument9 pagesQ-Sort Assessment of Attachment SecurityAna MariaNo ratings yet

- Adolescent-Parent Attachment and Externalizing Behavior: The Mediating Role of Individual and Social FactorsDocument12 pagesAdolescent-Parent Attachment and Externalizing Behavior: The Mediating Role of Individual and Social FactorsMario Manuel Fiorentino FerreyrosNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Attachment TheoryDocument8 pagesDissertation Attachment TheoryPaySomeoneToWritePaperCanada100% (1)

- 03 Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg COP 2019 Bridges-Across-The-Intergenerational-transmission - 2019Document6 pages03 Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg COP 2019 Bridges-Across-The-Intergenerational-transmission - 2019Ivania ZuñigaNo ratings yet

- Attachment in The Classroom, Bergin and Bergin, 2009.Document30 pagesAttachment in The Classroom, Bergin and Bergin, 2009.Esteli189100% (1)

- Child Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleDocument10 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleAlexandraNo ratings yet

- hooper2007Document13 pageshooper2007Réka SnakóczkiNo ratings yet

- Early Attachment Organization With Both Parents and Child Behavior ProblemsDocument21 pagesEarly Attachment Organization With Both Parents and Child Behavior ProblemsBozdog DanielNo ratings yet

- Parental Rearing, Attachment, and Social Anxiety in Chinese AdolescentsDocument21 pagesParental Rearing, Attachment, and Social Anxiety in Chinese AdolescentsTaleb LahcenNo ratings yet

- Bridges Across The Intergenerational Transmission of Attachment GapDocument6 pagesBridges Across The Intergenerational Transmission of Attachment GapBozdog DanielNo ratings yet

- Fostering Security A Meta Analysis of Attachment in Adopted Children - 2009 - Children and Youth Services Review PDFDocument12 pagesFostering Security A Meta Analysis of Attachment in Adopted Children - 2009 - Children and Youth Services Review PDFArielNo ratings yet

- A Learning Theory Approach To Attachment Theory: Exploring Clinical ApplicationsDocument22 pagesA Learning Theory Approach To Attachment Theory: Exploring Clinical ApplicationsCláudioToméNo ratings yet

- Joint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskDocument14 pagesJoint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskCarolina Saavedra MellaNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Maternal Sensitivity: Mothers' Comments On Infants' Mental Processes Predict Security of Attachment at 12 MonthsDocument12 pagesRethinking Maternal Sensitivity: Mothers' Comments On Infants' Mental Processes Predict Security of Attachment at 12 Monthsdaniela74848No ratings yet

- The Origins of Individual Differences in Infant-Mother Attachment - Jay BetskyDocument12 pagesThe Origins of Individual Differences in Infant-Mother Attachment - Jay BetskyJorge Roldán OrtizNo ratings yet

- Attachment_in_adultsDocument16 pagesAttachment_in_adultssofiadequeirosNo ratings yet

- Ppa 1987Document31 pagesPpa 1987Hoàng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Creatingasecurefamilybase PDFDocument10 pagesCreatingasecurefamilybase PDFinetwork2001No ratings yet

- Bounding 2Document11 pagesBounding 2Deliana MonizNo ratings yet

- Brenning Et Al. JCFSDocument12 pagesBrenning Et Al. JCFSsNo ratings yet

- Parenting As Relationship: A Framework For Assessment and PracticeDocument18 pagesParenting As Relationship: A Framework For Assessment and PracticeAna Rita SerraNo ratings yet

- Disorganized Attachment in Early Childhood - Van Ijzendoorn (Complementario)Document25 pagesDisorganized Attachment in Early Childhood - Van Ijzendoorn (Complementario)Helier Ignacio Fuster aguayoNo ratings yet

- Litrev 4Document11 pagesLitrev 4Selly MauriceNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamDocument8 pagesPersonality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamkakonautaNo ratings yet

- Waters2012 PDFDocument9 pagesWaters2012 PDFKaycee ManabatNo ratings yet

- Recollected Caregivers Sensitivity and Adult AttachmentDocument7 pagesRecollected Caregivers Sensitivity and Adult AttachmentBozdog DanielNo ratings yet

- Theory PaperDocument6 pagesTheory Paperapi-649875808No ratings yet

- Centre of Excellence For Early Childhood Development (2006) Attachment - Enciclopedia Early ChildDocument76 pagesCentre of Excellence For Early Childhood Development (2006) Attachment - Enciclopedia Early ChildAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Embarazo y ApegoDocument12 pagesEmbarazo y ApegoMary Belen Barria VillarroelNo ratings yet

- Simpson R Holes Nelligan J PSP 1992Document14 pagesSimpson R Holes Nelligan J PSP 1992Andreea MirsoleaNo ratings yet

- Connect and Shape: A Parenting Meta-Strategy Combines Behavioral and Relational ApproachesDocument4 pagesConnect and Shape: A Parenting Meta-Strategy Combines Behavioral and Relational ApproachesDanielBarreroNo ratings yet

- Found in Samples of High-Risk Infants and Toddlers: Patterns of Very Insecure AttachmentDocument17 pagesFound in Samples of High-Risk Infants and Toddlers: Patterns of Very Insecure AttachmentGlăvan AncaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Children's Emotional Security As A Mediator Og The Link Between Marital Relations and ChildDocument17 pagesExploring Children's Emotional Security As A Mediator Og The Link Between Marital Relations and ChildNtahpepe LaNo ratings yet

- Affrunti Et Al - 2015 - Language of Perfectionistic Parents Predicting Child AnxietyDocument9 pagesAffrunti Et Al - 2015 - Language of Perfectionistic Parents Predicting Child AnxietyEmese HruskaNo ratings yet

- Emotion Reactivity and Regulation in Maltreated Children: A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesEmotion Reactivity and Regulation in Maltreated Children: A Meta-AnalysisRealidades InfinitasNo ratings yet

- Shaping Your Child's Healthy Self-Esteem-Self-Worth: Emotional IntelligenceFrom EverandShaping Your Child's Healthy Self-Esteem-Self-Worth: Emotional IntelligenceNo ratings yet

- Q1 Week1-2 BiotechDocument43 pagesQ1 Week1-2 Biotechmarivic mirandaNo ratings yet

- Iso 16140 Validation by Afnor On TVC TC and Ec Adria-2 PDFDocument1 pageIso 16140 Validation by Afnor On TVC TC and Ec Adria-2 PDFJuliet RomeroNo ratings yet

- WHO 4th Intl Standard For HCVDocument2 pagesWHO 4th Intl Standard For HCVSagir AlvaNo ratings yet

- BBL™ Mueller Hinton Broth: - Rev. 02 - June 2012Document2 pagesBBL™ Mueller Hinton Broth: - Rev. 02 - June 2012Manam SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Chrysothemis PulchellaDocument2 pagesChrysothemis PulchellaTharayilsijNo ratings yet

- Botany MicrobiologyDocument89 pagesBotany Microbiologytarungupta2001No ratings yet

- Time 120Document3 pagesTime 120ardhra pNo ratings yet

- Science 7 - Summative Test - Q2 - PrintDocument2 pagesScience 7 - Summative Test - Q2 - PrintLenette AlagonNo ratings yet

- Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode ScriptsDocument208 pagesCosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scriptsjose.garcilaso5477No ratings yet

- Kahoot 1Document6 pagesKahoot 1Nida RidzuanNo ratings yet

- Exerise No.5 Reticulocyte Count: Routine Hematology Laboratory Student Manual Volume 1Document6 pagesExerise No.5 Reticulocyte Count: Routine Hematology Laboratory Student Manual Volume 1Jam RamosNo ratings yet

- 2oferta Arbusti Toamna2022Document3 pages2oferta Arbusti Toamna2022MariusTudoreanNo ratings yet

- The Land Bridge WorksheetDocument2 pagesThe Land Bridge Worksheetapi-306692383No ratings yet

- Bio 10th - Excretion - Extensive TestDocument1 pageBio 10th - Excretion - Extensive TestDharmendra SinghNo ratings yet

- Madhu VargDocument36 pagesMadhu VargYash GardhariyaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Successful Aging (Flood)Document4 pagesTheory of Successful Aging (Flood)Chinnie Nicole RamosNo ratings yet

- Heredity and EvolutionDocument29 pagesHeredity and EvolutionAnisha ThomasNo ratings yet

- E CA 72-4 en 9Document3 pagesE CA 72-4 en 9Hassan GillNo ratings yet

- iicc// - Aarrttw Woorrkk//Ccrriittiiqquuee: P Poosstt Aa R ReeppllyyDocument21 pagesiicc// - Aarrttw Woorrkk//Ccrriittiiqquuee: P Poosstt Aa R ReeppllyyhisohisoNo ratings yet

- Gce 221 NoteDocument18 pagesGce 221 NoteAyiri TieNo ratings yet

- Botany Class 11thDocument258 pagesBotany Class 11thwebdeveloperavinash28No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Understanding Pathophysiology 6th Edition by HuetherDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Understanding Pathophysiology 6th Edition by HuetherJulieCooperb25om100% (33)

- Chemical Analysis of MANOIR XM AlloyDocument3 pagesChemical Analysis of MANOIR XM Alloyogun tokucNo ratings yet

- LACTObacillUS SakeiDocument10 pagesLACTObacillUS SakeiNeder PastranaNo ratings yet

- Recommended Herbs Per Infection According To Stephen BuhnerDocument3 pagesRecommended Herbs Per Infection According To Stephen BuhnerYannick HsNo ratings yet