Professional Documents

Culture Documents

03 Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg COP 2019 Bridges-Across-The-Intergenerational-transmission - 2019

Uploaded by

Ivania ZuñigaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

03 Van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg COP 2019 Bridges-Across-The-Intergenerational-transmission - 2019

Uploaded by

Ivania ZuñigaCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

ScienceDirect

Bridges across the intergenerational transmission

of attachment gap

Marinus H van IJzendoorn1,2 and Marian J Bakermans-Kranenburg3

Attachment is transmitted from one generation to the next. Protective caregivers, in most cases the biological parents

Adult attachment has been shown to predict the security or and other biologically related adults or older siblings close

insecurity of children’s attachment relationship with their to them [3], respond to the attachment behaviors of the

parents. In search for the mechanism of intergenerational offspring by providing protection and food, and by regu-

transmission of attachment sensitive parenting has been the lating any negative emotions that threaten to overwhelm

main focus of research during the past four decades. Meta- the children in stressful situations. They bond to their

analytic work confirmed the role of sensitive parenting, but a children as a rewarding basis for their costly investment in

large explanatory gap remains to be explained. Parental the children’s development into adulthood, with the

mentalization has not yet fulfilled its promise as a bridge across functional consequence of enhanced inclusive fitness

the transmission gap. Here we suggest a model of and transmission of their genes into the next generations

intergenerational transmission that includes context and (Szepsenwol and Simpson, this issue).

differential susceptibility, and we argue that the concept of

parenting should be broadened to include autonomy support, Although every infant is born with the bias to become

limit-setting, protective parenting, parental warmth, and repair attached, the environment and in particular the caregivers

of mismatches. are critical in shaping individual differences in quality of

the attachment relationship. Analogous to children born

Addresses with the innate capacity to learn a language and are

1

Department of Psychology, Education and Child Studies, Erasmus dependent on the environment for learning a specific

University Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2

language, the inborn attachment bias can be canalized in

Primary Care Unit, School of Clinical Medicine, University of different directions — secure or insecure — dependent

Cambridge, UK

3

Graduate School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Leiden University,

on the parents who prepare their children to survive

The Netherlands and adapt to a specific bioecological niche [4].

Corresponding author: van IJzendoorn, Marinus H (vanijzendoorn@essb.

eur.nl) Transmission of attachment: connection of

two core hypotheses

A first core hypothesis of attachment theory is the crucial

Current Opinion in Psychology 2018, 25:31–36

role of parental sensitive responsiveness to infant attach-

This review comes from a themed issue on Attachment in adulthood ment signals in shaping individual differences in attach-

Edited by Jeffry A Simpson and Gery Karantzas ment. Parental sensitive responsiveness has been defined

as the capacity of caregivers to take notice of the child’s

attachment signals, to interpret them correctly, and to

respond to them promptly and adequately [5]. Correla-

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.014 tional as well as experimental studies have documented

2352-250/ã 2018 Published by Elsevier Ltd. that more sensitive parents elevate the chance that their

child becomes securely attached, meaning that the child

strikes a balance between exploration and proximity

seeking. The secure child is free to explore the environ-

ment and at the same time is ready to seek proximity to

the trusted caregiver in times of stress. By contrast,

Attachment is the evolutionary rooted, innate bias of any insensitive parents trigger an insecure attachment in their

human infant to seek proximity to protective caregivers child who remains vigilant and stressed even when the

who serve as a safe base to explore the environment and a caregiver is nearby [6,7!!].

safe haven to return to in times of distress, danger, or

illness [1]. In the first years after birth this attachment bias A second core hypothesis of attachment theory is the

is not only crucial for protection against predators and influence of early attachment experiences on later socio-

other potentially deadly external dangers but also for emotional functioning, which may extend to adult attach-

thermoregulation and other biobehavioral regulatory pro- ment and parenting. Attachment relationships with par-

cesses that enhance survival to procreative age, and thus ents and other attachment figures in childhood and

attachment contributes to the inclusive fitness of the thereafter serve as mental models that shape parents’

parents [2!!]. interactions and attachment relationships with their

www.sciencedirect.com Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36

32 Attachment in adulthood

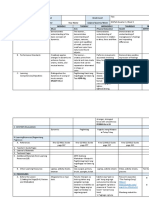

Figure 1

Infant Infant

Adult Attachment

Parenting Attachment Attachment

Representation

Behavior Classification

Autonomous (F) sensitive balanced Secure (B)

non-distress:

Dismissing (Ds) sensitive minimizing Avoidant (A)

distress:

insensitive

non-distress:

Preoccupied (E) insensitive maximizing Resistant (C)

distress:

sensitive

Current Opinion in Psychology

Intergenerational transmission of attachment. Hypothetical links between adult attachment representations, parenting behavior in distress and non-

distress contexts, infant attachment behavior, and infant attachment classifications.

offspring [8!!]. This is the hypothesis of intergenerational Psychometric studies have shown that the AAI indeed is

transmission of attachment, which states that the current independent of non-attachment related autobiographical

mental representation of childhood attachment experi- memory, verbal IQ, and SES [11]. It should be noted that

ences, that is, adult attachment, influences their child’s this is specific to adult attachment representations and not

attachment relationship with them. Note that the mental attachment styles [12], and that for the sake of concise-

representation of attachment need not coincide with ness we do not discuss the AAI in relation to loss or other

actual attachment experiences during childhood — there potentially traumatic events [10!!,13].

is a crucial move to the level of representation.

Transmission of attachment through sensitive

Move from child attachment behavior to adult parenting

attachment representation Combining the two core hypotheses we arrive at the basic

This move to the level of representation is operationa- model for intergenerational transmission of attachment

lized by Main and colleagues in an interview to assess the that has been studied intensively in the past four decades.

current representation of attachment in adults, the Adult Adult attachment predicts child attachment, or more

Attachment Interview (AAI) [8!!]. Whereas infant attach- specifically: coherence of the parental narrative about

ment behavior can readily be observed in a mildly stress- attachment experiences predicts the child’s balance

ful setting such as the Strange Situation Procedure, a between exploration and proximity seeking. Parents with

separation–reunion procedure that elicits infant attach- an angry, preoccupied perspective on the way they were

ment behavior [9], adult attachment can be derived from treated by their parents elevate the chance that their child

the adults’ narrative during the hour-long AAI that asks develops an insecure-resistant attachment, whereas par-

for general descriptors of attachment experiences and ents who dismiss the impact or memory of negative

concrete episodic memories illustrating these descriptors. attachment experiences unwillingly stimulate an inse-

cure-avoidant attachment in their child. Resistant chil-

The AAI coding system presents coherence of the auto- dren maximize their attachment behavior at the cost of

biographical narrative as the essential characteristic dif- exploration, avoidant children minimize the expression of

ferentiating adults with secure versus insecure represen- their attachment needs.

tations of attachment. Unique to this interview is that it

does not rely on the content of autobiographical retro- Parental sensitive responsiveness to child signals is

spection but on the formal features of the narrative, in hypothesized to mediate the association between adult

particular linguistic coherence. Regardless of specific and child attachment (see Figure 1). Preoccupied parents

childhood events or experiences, security or insecurity tend to show inconsistently sensitive responses: they are

of adult attachment representations is derived from the insensitive to low-intensity attachment signals of their

coherence of the verbatim transcribed narrative [10!!]. child but are usually sensitive to high-intensity signals

Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36 www.sciencedirect.com

Bridges across the intergenerational transmission of attachment gap van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg 33

such as crying. By contrast, insecure-dismissing parents Figure 2

are supportive of their child in stress-free conditions but

disconnect when the child shows signs of discomfort and

distress, questioning the parental capacity to deal with the adult

child’s negative emotions [14,15]. attachment

The intergenerational transmission gap

Almost 25 years ago the intergenerational transmission stressors

TRANSMISSION

gap was introduced [16,17]. This gap points to the unex-

plained transmission of attachment: Despite strong meta-

analytic evidence for the association between adult and

GAP

child attachment [16], and similarly robust meta-analytic sensitivity

evidence for the causal role of parental sensitive respon-

siveness in shaping child attachment security [6] parental

sensitivity only partially mediates the relation between susceptibility

adult and child attachment. In a meta-analytic path model

on N = 854 parent–child dyads, about 75% of the associa-

tion between adult attachment and child attachment was

left unexplained by sensitive parenting: the transmission infant

gap. attachment

Current Opinion in Psychology

The most recent meta-analytic replication on

N = 4819 dyads showed a smaller but still substantial

Transmission of attachment and transmission gap. Intergenerational

transmission gap of somewhat less than 50% [18!!]. After transmission of attachment, mediated by parenting sensitivity.

more than four decades of research and almost 100 attach- Mediation by parenting sensitivity decreases — accompanied by an

ment studies we still are in the dark about the mechanism increase of the transmission gap — as a result of (1) variation in

of the transmission of attachment across generations. The environmental stressors moderating the association between adult

attachment and parenting sensitivity, and (2) variation in infant

recent meta-analysis offers some clues where to look for susceptibility moderating the association between parenting sensitivity

other mechanisms than parental sensitivity or for mod- and infant attachment.

erators pointing at conditions in which the transmission is

marginal or even absent.

childhood attachment experiences in an incoherent man-

Moderators of the intergenerational ner and are insensitive caregivers have secure children

transmission gap because differential susceptibility to the environment

Moderators point to conditions in which intergenerational serves as a moderator (see Figure 2). Belsky [21] was

transmission of attachment is stronger, or, on the oppo- the first to emphasize differential susceptibility of chil-

site, hampered or blocked (see Figure 2). In families at dren to parental sensitive responsiveness, speculating

risk, for example, because of teenage motherhood, inter- that the more difficult, irritable, emotionally negative

generational transmission of attachment was absent, and or reactive children would be most influenced by parent-

the mediation model of the transmission gap appeared to ing, whereas easy-going children would be less

be obsolete. In such circumstances, adult attachment of impressed, for better and for worse [22,23]. In recent

caregivers seems to lose its power to predict child attach- years, evidence for the role of difficult temperament as a

ment, and other mechanisms take over, such as the marker of differential susceptibility has indeed accumu-

influence of active grandparents [19]. Cumulative adver- lated [24]. Thus, the temperamentally easy-going chil-

sities can interfere with the parent’s sensitivity compe- dren of insecure parents may develop into a secure

tence to be translated into actual performance (see Fig- trajectory despite the less than optimal caregiving they

ure 2). In the communal kibbutzim, with collective receive and despite conclusive evidence that tempera-

sleeping arrangements outside the family home for ment and attachment are not associated [25]. In Figure 3

infants within a few months after birth, secure parents the various hypothetical pathways have been presented.

did not establish secure attachment relationships with Secure parents may have secure children even if they

their infants because of ‘contextual neglect’, that is lack of experience stresses and adversities triggering insensitive

interaction time and unavailability when their infants parenting when these children are less susceptible to

were distressed during the night in the first few years environmental input. In case of children’s high suscepti-

of life [20]. bility secure parents in stressful circumstances (hamper-

ing their sensitivity) have an increased risk for insecure

Intergenerational transmission of attachment does also child–parent attachment. Insecure parents might show

not occur when parents who as adults talk about their sensitive parenting when they are adequately supported,

www.sciencedirect.com Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36

34 Attachment in adulthood

Figure 3

adult attachment secure insecure

context stress support

parenting insensitive sensitive insensitive

susceptibility low high low high low high

infant attachment secure insecure secure insecure

Current Opinion in Psychology

Parenting, context, and differential susceptibility in the transmission of secure and insecure attachment. Intergenerational transmission of

attachment, taking into account environmental context and infant differential susceptibility. Blue lines represent intergenerational transmission

mediated by parenting sensitivity. Red lines represent intergenerational transmission not mediated by parenting sensitivity, indicating a

transmission gap.

for example through their social network or with parent- Mentalization has three components: parental mind-

ing interventions, and if their children are highly suscep- mindedness, parental insightfulness, and parental reflec-

tible they may develop a secure attachment; when the tive functioning [29]. Parental mentalization is usually

children however are less susceptible they may be inse- assessed in an interview with the parent about the child’s

cure or secure but independent of parenting quality. thoughts and feelings (with the exception of few obser-

vational mind-mindedness studies of parent–infant

If child secure or insecure attachment were genetically dyads), and high mentalization points at the capacity to

determined, genetic make-up could against the odds describe the world from the child’s perspective.

override the environmental influence of an insecure or

secure caregiver and lead to a secure or insecure attach- Parental mentalization is therefore not a dimension or

ment. The meta-analytic finding that biological related- feature of parenting behavior but a mental or cognitive

ness of child–caregiver dyads moderates the intergenera- capacity that might be expressed in parental behavior to

tional transmission of attachment seems to leave some the child. It is only parental behavior that is visible to the

room for this speculation, as the transmission appeared to child. Children are unable — like us all — to observe

be only present in genetically related pairs [18!!]. How- what is going on in the mind of the parent, or in their

ever, direct evidence for genetically determined child brain for that matter, at least not without imaging tech-

attachment differences is scarce [26]. niques. A meta-analysis shows that both mentalization

and sensitivity explain parts of the variance in child

Mentalization bridging the gap? attachment security [29]. Because adult attachment was

The transmission gap is the consequence of strong evi- not included the findings cannot be helpful in bridging

dence for intergenerational transmission of attachment, the transmission gap. Mentalization could perhaps be

that is, from adult attachment to the child–parent attach- considered a proxy of adult attachment; meta-analytically

ment relationship. The Adult Attachment Interview pre- it explained 9% of the variance in child attachment

dicts child behavior in the Strange Situation Procedure, security. The indirect pathway of mentalization via sen-

even when the AAI is conducted prenatally and the SSP a sitivity to attachment explained less than 1% of the

year after birth [27]. But insight into the mechanisms of variance in child attachment [29], thus a transmission

the transmission is incomplete, as evidence for the sim- gap of 89% (8/9) remains.

plest transmission model with parental sensitivity as the

only mediator between adult and child attachment docu- Promising building bricks for bridging the gap

ments [28!!]. A wide transmission gap remains, even after Complementing the current components of the intergen-

almost 100 studies and thousands of participating families. erational transmission of attachment model seems most

promising to bridge the transmission gap. First, we might

A large literature addresses the puzzle of the transmission look for mental representations of parents evolving from

gap by focusing on ‘parental mentalization’ defined as adult attachment but closer to their parenting practices.

‘the degree to which parents show frequent, coherent, or Parental mentalization of the child’s thoughts and feel-

appropriate appreciation of their infants’ internal states’. ings is a plausible candidate for narrowing the gap with

Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36 www.sciencedirect.com

Bridges across the intergenerational transmission of attachment gap van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg 35

child attachment, although the recent meta-analytic data 5. Ainsworth MDS, Bell S, Stayton D: Infant–mother attachment and

social development. In The Introduction of the Child into a Social

do not seem promising in this regard. Adaptation of the World. Edited by Richards MP. University Press; 1974:99-135.

Secure Base Script Knowledge (SBKS) to the AAI tran- 6. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F: Less is

scripts might be another, more reliable way to go forward more: meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment

(see also Waters and Roisman, this issue). interventions in early childhood. Psychol Bull 2003, 129:195-215

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195.

7. Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins WA: The Development

Second, we may broaden our perspective on attachment- !! of the Person. Guilford; 2011.

relevant parenting. Plausible candidates beyond parental Major work integrating the findings from the Minnesota Longitudinal

sensitivity would be autonomy support [30], limit setting Study spanning the life course from infancy to adulthood, from an

attachment perspective.

[31], protective parenting [32], entropy [33], synchrony

[34!!] and repair of mismatches [35] in parent–child 8.

!!

Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J: Security in infancy, childhood, and

adulthood: a move to the level of representation. In Growing

interactions. A special emphasis on stressful and distres- Points of Attachment Theory and Research. Monographs of the

sing situations for children [15] as well as for parents [36] Society for Research in Child Development, 50. Edited by

Bretherton I, Waters E . 1985:66-104 http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/

might create a more informative window on attachment- 3333827.

related parenting as attachment is especially operational Groundbreaking paper on the move to the level of attachment represen-

tations introducing the Adult Attachment Interview.

in situations that are difficult for the child to cope with on

its own, and undivided parental attention is needed. 9. Ainsworth MD, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S: Patterns of

Attachment. Erlbaum; 1978.

Third, child attachment still is volatile in the first few 10. Hesse E: The adult attachment interview: protocol, method of

!! analysis, and empirical studies: 1985–2015. In Handbook of

years of life, as the child’s experiences with attachment Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited

figures cumulate into a more or less fixed but still by Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Guilford Press; 2016.

The only complete overview of the Adult Attachment Interview and the

‘working model’ of attachment [1]. This points to the numerous studies conducted with this measure in the past few decades.

urgent need to observe child attachment at several time-

11. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH: A

points, in a variety of settings, and during longer stretches psychometric study of the Adult Attachment Interview:

of time [30]. Ambulatory assessments become more reli- reliability and discriminant validity. Dev Psychol 1993, 29:870-

880.

able and easy to use [37] and provide detailed observa-

tions of the environment, parent–child interactions and 12. Verhage ML, Schuengel C, Fearon RMP, Madigan S,

Oosterman M, Cassibba R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van

child neurobiological parameters relevant for building the IJzendoorn MH: Failing the Duck Test: Reply to Barbaro,

bridge between adult and child attachment. Boutwell, Barnes, and Shackelford (2017). Psych Bull 2017,

143:114-116.

13. Madigan S, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH,

Conflict of interest statement Moran G, Pederson DR, Benoit D: Unresolved states of mind,

anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: a

Nothing declared. review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attach Hum

Develop 2006, 8:89-111 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/

14616730600774458.

Acknowledgements 14. Fearon RMP, Belsky J: Precursors of attachment security. In

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the European Research Council Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical

(ERC AdG, MJBK, grant number 669249), and the Netherlands Applications. Edited by Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Guilford Press;

Organization for Scientific Research (Spinoza, MHvIJ), as well as the 2016.

Gravitation program of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and 15. Leerkes EM, Zhou N: Maternal sensitivity to distress and

Science and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO attachment outcomes: interactions with sensitivity to non-

grant number 024.001.003). distress and infant temperament. J Fam Psychol, in press.

16. Van IJzendoorn MH: Adult attachment representations,

parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: a meta-

References and recommended reading analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, Interview. Psych Bull 1995, 117:387-403 http://dx.doi.org/

have been highlighted as: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387.

!! of outstanding interest 17. Van IJzendoorn MH: Of the way we are. On temperament,

attachment and the transmission gap. A rejoinder to Fox.

1. Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss: vol 1. Attachment. edn 2. Basic Psych Bull 1995, 117:411-415.

Books; 1982. (Original work published 1969).

18. Verhage ML, Schuengel C, Madigan S, Fearon RM, Oosterman M,

2. Cassidy J: The nature of the child’s ties. In Handbook of !! Cassibba R, van IJzendoorn MH: Narrowing the transmission

!! Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited gap: a synthesis of three decades of research on

by Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Guilford Press; 2016. intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psych Bull 2016,

Concise summary of the recent state-of-the-art in attachment theory and 142:337-366 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000038.

research. The intergenerational transmission gap revisited through an exhaustive

meta-analysis, resulting in a narrower but still existing gap.

3. Hrdy SB: Mother Nature. Maternal Instincts and How they Shape

the Human Species. Ballantine; 1999. 19. Benoit D, Parker KCH: Stability and transmission of attachment

across three generations. Child Dev 1994, 65:1444-1456 http://

4. Simpson JA, Belsky J: Attachment theory within a modern dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131510.

evolutionary framework. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory,

Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited by Cassidy J, Shaver 20. Sagi A, Van IJzendoorn MH, Scharf M, Joels T, Koren-Karie N,

PR. Guilford Press; 2016. Mayseless O, Aviezer O: Ecological constraints for

www.sciencedirect.com Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36

36 Attachment in adulthood

intergenerational transmission of attachment. Int J Behav Dev predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychol Bull 2017

1997, 20:287-299 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/016502597385342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000114. August 14, Advance online

publication.

21. Belsky J: Theory testing, effect-size evaluation, and differential

susceptibility to rearing influence: the case of mothering and 30. Bernier A, Matte-Gagné C, Bélanger MÈ, Whipple N: Taking stock

attachment. Child Dev 1997, 68:598-600 http://dx.doi.org/ of two decades of attachment transmission gap: broadening

10.2307/1132110. the assessment of maternal behavior. Child Dev 2014, 85:1852-

1865 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12236.

22. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH: The hidden

efficacy of interventions: gene environment experiments from 31. Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH: Pairing

a differential susceptibility perspective. Ann Rev Psychol 2015, attachment theory and social learning theory in video-

66:381-409 http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814- feedback intervention to promote positive parenting. Curr Opin

015407. Psychol 2017, 15:189-194.

23. Belsky J, Van IJzendoorn MH: Genetic differential susceptibility 32. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH: Protective

to the effects of parenting. Curr Opin Psychol 2017, 15:125-130. parenting: neurobiological and behavioral dimensions. Curr

! M, Van Aken MAG: Differences in Opin Psychol 2017, 15:45-49.

24. Slagt M, Dubas JS, Dekovic

sensitivity to parenting depending on child temperament: a 33. Davis EP, Davisa EP, Stouta SA, Molet J, Vegetabile B, Glynn LM,

meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2016, 142:1068-1110 http://dx.doi. Sandman CA, Heins K, Stern H, Baram TZ: Exposure to

org/10.1037/bul0000061. unpredictable maternal sensory signals influences cognitive

25. Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ: Integrating development across species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017,

temperament and attachment: the differential susceptibility 114:10390-10395.

paradigm. In Handbook of Temperament. Edited by Zentner M,

34. Feldman R: Mutual influences between child emotion

Shiner RL. Guilford Press; 2015.

!! regulation and parent–child reciprocity support development

26. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH: Attachment, across the first 10 years of life: implications for developmental

parenting, and genetics. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 2015, 27:1007-1023.

Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited by Cassidy J, Shaver Synchrony studied at various levels of functioning, from hormonal to

PR. Guilford Press; 2016. behavioral interactions between parent and child, and thus going beyond

traditional sensitivity assessments.

27. Fonagy P, Steele H, Steele M: Maternal representations of

attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of 35. Beebe B, Steele M: How does microanalysis of mother–infant

infant–mother attachment at one year of age. Child Dev 1991, communication inform maternal sensitivity and infant

62:891-905 http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131141. attachment? Attach Hum Dev 2013, 15:583-602.

28. Fearon RMP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Groh AM, Roisman GI, 36. Pederson DR, Moran G, Sitko C, Campbell K: Maternal sensitivity

!! Van IJzendoorn MH: Attachment and developmental and the security of infant–mother attachment: a Q-sort study.

psychopathology. In Developmental Psychopathology. Edited Child Dev 1990, 61:1974-1983.

by Cicchetti D. Wiley; 2016.

Almost book-length treatise of attachment theory and research with 37. Wilhelm FH, Grossman P, Muller MI: Bridging the gap between

special emphasis on the clinical applications. the laboratory and the real world: integrative ambulatory

psychophysiology. In Handbook of Research Methods for

29. Zeegers MAJ, Colonnesi C, Stams GJM, Meins E: Mind matters: a Studying Daily Life. Edited by Mehl MR, Conner TS. Guilford Press;

meta-analysis on parental mentalization and sensitivity as 2012:210-234.

Current Opinion in Psychology 2019, 25:31–36 www.sciencedirect.com

You might also like

- Bridges Across The Intergenerational Transmission of Attachment GapDocument6 pagesBridges Across The Intergenerational Transmission of Attachment GapBozdog DanielNo ratings yet

- Is Insecure Parent - Child Attachment A Risk Factor For The Development of Anxiety in Childhood or Adolescence?Document6 pagesIs Insecure Parent - Child Attachment A Risk Factor For The Development of Anxiety in Childhood or Adolescence?Susan KuriakoseNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Enhancing Attachment Organization Among Maltreated Children: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument20 pagesNIH Public Access: Enhancing Attachment Organization Among Maltreated Children: Results of A Randomized Clinical TrialPyaePhyoAungNo ratings yet

- In-Service Assignment AttachmentDocument14 pagesIn-Service Assignment Attachmentapi-549471770No ratings yet

- Disorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeDocument25 pagesDisorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeGabe MartindaleNo ratings yet

- Fostering Security A Meta Analysis of Attachment in Adopted Children - 2009 - Children and Youth Services Review PDFDocument12 pagesFostering Security A Meta Analysis of Attachment in Adopted Children - 2009 - Children and Youth Services Review PDFArielNo ratings yet

- Breidenstine 2011 Attachment Trauma EarlyChildhoodDocument17 pagesBreidenstine 2011 Attachment Trauma EarlyChildhoodAmalia PagratiNo ratings yet

- Sustained Attention in Infancy - A Foundation For The Development of Multiple Aspects of Self-Regulation For Children in PovertyDocument18 pagesSustained Attention in Infancy - A Foundation For The Development of Multiple Aspects of Self-Regulation For Children in PovertyMACARENA VASQUEZ TORRESNo ratings yet

- Thinking About Children's Attachments: ReviewDocument8 pagesThinking About Children's Attachments: Reviewningogo21No ratings yet

- The DIR Model (Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship Based) : A Parent Mediated Mental Health Approach To Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument11 pagesThe DIR Model (Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship Based) : A Parent Mediated Mental Health Approach To Autism Spectrum DisordersLaisy LimeiraNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Trauma in Early ChildhoodDocument18 pagesAttachment and Trauma in Early ChildhoodAnonymous KrfJpXb4iNNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Preschool Teacher. An Opportunity To Develop A Secure BaseDocument16 pagesAttachment and Preschool Teacher. An Opportunity To Develop A Secure BaseRoxana MedinaNo ratings yet

- Communicating With Children and Adolescents-3Document8 pagesCommunicating With Children and Adolescents-3AANo ratings yet

- PSYCH101 Wiki Attachment TheoryDocument25 pagesPSYCH101 Wiki Attachment TheoryMadalina-Adriana ChihaiaNo ratings yet

- QOC Sig 4 PDFDocument18 pagesQOC Sig 4 PDFinetwork2001No ratings yet

- Childhood Attachment: Healthy and Unhealthy AttachmentDocument3 pagesChildhood Attachment: Healthy and Unhealthy AttachmentRoxana CGhNo ratings yet

- Litrev 4Document11 pagesLitrev 4Selly MauriceNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 01064 v3Document22 pagesIjerph 19 01064 v3Camila Sofía Díaz OyarzúnNo ratings yet

- Attachment in The Classroom, Bergin and Bergin, 2009.Document30 pagesAttachment in The Classroom, Bergin and Bergin, 2009.Esteli189100% (1)

- Recollected Caregivers Sensitivity and Adult AttachmentDocument7 pagesRecollected Caregivers Sensitivity and Adult AttachmentBozdog DanielNo ratings yet

- Neglect TestDocument11 pagesNeglect Testganeshwari 011No ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument80 pagesAttachmentanantheshkNo ratings yet

- 1271 The Verdict Is in PDFDocument12 pages1271 The Verdict Is in PDFinetwork2001No ratings yet

- The Infant Disorganised Attachment Classification Patt 2018 Social ScienceDocument7 pagesThe Infant Disorganised Attachment Classification Patt 2018 Social Sciencenafisatmuhammed452No ratings yet

- Nihms 779728Document31 pagesNihms 779728Corina IoanaNo ratings yet

- TheContentsofIndonesianchild ParentsattachmentDocument66 pagesTheContentsofIndonesianchild ParentsattachmentWindyNo ratings yet

- John Bowlby-Attachment TheoryDocument13 pagesJohn Bowlby-Attachment Theoryapi-302132755100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0022096522001631 Main 2Document15 pages1 s2.0 S0022096522001631 Main 2Danial S. SaktiNo ratings yet

- Perdon en NiñosDocument5 pagesPerdon en NiñosCels ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0163638318301978 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0163638318301978 MainLoladaNo ratings yet

- Erickson 1985Document21 pagesErickson 1985Annisa IkhwanusNo ratings yet

- The Sage Encyclopedia of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders I2233Document5 pagesThe Sage Encyclopedia of Intellectual and Developmental Disorders I2233pollomaximus 444No ratings yet

- Attachment Between Infant and CaregiverDocument41 pagesAttachment Between Infant and CaregiverPatti Garrison ReedNo ratings yet

- Levigouroux 2017Document4 pagesLevigouroux 2017II. félév PTEpszichológiaNo ratings yet

- Attachment DisordersDocument9 pagesAttachment DisordersALNo ratings yet

- The Verdict Is In: The Case For Attachment TheoryDocument11 pagesThe Verdict Is In: The Case For Attachment TheoryELISA ANDRADENo ratings yet

- Attachment and Foster CareDocument14 pagesAttachment and Foster CareProdan Dumitru DanielNo ratings yet

- JOHN BOWLBY: Attachment Theory: Quenie de BaereDocument11 pagesJOHN BOWLBY: Attachment Theory: Quenie de BaereMae OponNo ratings yet

- Centre of Excellence For Early Childhood Development (2006) Attachment - Enciclopedia Early ChildDocument76 pagesCentre of Excellence For Early Childhood Development (2006) Attachment - Enciclopedia Early ChildAna FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Maternal Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument11 pagesMaternal Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Child and Adolescent DevelopmentLeonardo PunshonNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamDocument8 pagesPersonality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamkakonautaNo ratings yet

- Edit Jan 2019Document12 pagesEdit Jan 2019shreyancejainNo ratings yet

- Terapia Inhibicion de ImpulsosDocument11 pagesTerapia Inhibicion de ImpulsosVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- Infant Behavior and DevelopmentDocument9 pagesInfant Behavior and DevelopmentMildred HickieNo ratings yet

- Child Personality and Parental Behavior As Moderators of Problem Behavior: Variable-And Person-Centered ApproachesDocument19 pagesChild Personality and Parental Behavior As Moderators of Problem Behavior: Variable-And Person-Centered ApproachesSetiaji CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Protecting The Psychological Health of Children Through Effective Communication About COVID-19 PDFDocument2 pagesProtecting The Psychological Health of Children Through Effective Communication About COVID-19 PDFJorge MartínezNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Maternal Sensitivity: Mothers' Comments On Infants' Mental Processes Predict Security of Attachment at 12 MonthsDocument12 pagesRethinking Maternal Sensitivity: Mothers' Comments On Infants' Mental Processes Predict Security of Attachment at 12 Monthsdaniela74848No ratings yet

- Dissertation Attachment TheoryDocument8 pagesDissertation Attachment TheoryPaySomeoneToWritePaperCanada100% (1)

- Attachment in AdultsDocument16 pagesAttachment in AdultssofiadequeirosNo ratings yet

- Mental Representations of Attachment Among Prospective Australian FathersDocument7 pagesMental Representations of Attachment Among Prospective Australian FathersAdrienn MatheNo ratings yet

- Theme 5.1Document3 pagesTheme 5.1matguay9No ratings yet

- Social and Personality Development in Childhood - NobaDocument11 pagesSocial and Personality Development in Childhood - Nobapqsvbgpjy5No ratings yet

- Theory of LoveDocument6 pagesTheory of LoveShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Attachment in AdolescenceDocument17 pagesAttachment in AdolescenceMário Jorge100% (1)

- Child Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleDocument10 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleLamiaNo ratings yet

- Connect and ShapeDocument4 pagesConnect and ShapeDanielBarreroNo ratings yet

- Attachment in Social DevelopmentDocument18 pagesAttachment in Social DevelopmentRameen BabarNo ratings yet

- Sroufe A Siegel D The Verdict Is in The Case For Attachment TheoryDocument9 pagesSroufe A Siegel D The Verdict Is in The Case For Attachment TheoryAkshat AnandNo ratings yet

- The Key Person Approach: Positive Relationships in the Early YearsFrom EverandThe Key Person Approach: Positive Relationships in the Early YearsNo ratings yet

- A level Psychology Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsFrom EverandA level Psychology Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- L O 1 Prepare To Assemble Electronic ProductsDocument4 pagesL O 1 Prepare To Assemble Electronic ProductsRamramramManmanmanNo ratings yet

- 4567 Main StreetDocument3 pages4567 Main StreetNajus NaaNo ratings yet

- StranoNeural Network Criminal ProfilingDocument39 pagesStranoNeural Network Criminal ProfilingjaverianaNo ratings yet

- Benjamin & Barthes - KeenanDocument6 pagesBenjamin & Barthes - KeenanAiswarya JayamohanNo ratings yet

- RoutledgeHandbooks 9780203068632 Chapter3Document13 pagesRoutledgeHandbooks 9780203068632 Chapter3Gligor BozinoskiNo ratings yet

- Phlebotomy ResumeDocument2 pagesPhlebotomy Resumeapi-452914737No ratings yet

- Environment of HRMDocument12 pagesEnvironment of HRMmycreation18No ratings yet

- Lent 2011Document9 pagesLent 2011Marcelo SoaresNo ratings yet

- Consumer InvolvementDocument14 pagesConsumer InvolvementkaranchouhanNo ratings yet

- DLL MAPeH-2 Q3W5Document13 pagesDLL MAPeH-2 Q3W5PRINCESS GARGARNo ratings yet

- Avon Cosmetics Inc F. Pimentel Ave., Purok 1, Bgry. Cobangbang, Daet, Camarines Norte 4600 PH. VAT Reg.: TIN 000-107-629-014Document4 pagesAvon Cosmetics Inc F. Pimentel Ave., Purok 1, Bgry. Cobangbang, Daet, Camarines Norte 4600 PH. VAT Reg.: TIN 000-107-629-014Patricia Nicole De JuanNo ratings yet

- Lindsey Morin - Resume 2019Document2 pagesLindsey Morin - Resume 2019api-455504401No ratings yet

- Activity Sheet in English 10: Worksheet No. 4.1, Quarter 4Document6 pagesActivity Sheet in English 10: Worksheet No. 4.1, Quarter 4Dhaiiganda100% (3)

- Effects of Self-Instruction and Time Management TeDocument10 pagesEffects of Self-Instruction and Time Management TeVernonNo ratings yet

- Addictive Food 1.6 Activity 1. Translate The Following VocabularyDocument4 pagesAddictive Food 1.6 Activity 1. Translate The Following VocabularyDaniela BenettNo ratings yet

- Holistic Grammar TeachingDocument3 pagesHolistic Grammar Teachingmangum1No ratings yet

- Endroit: The Art of TravelingDocument93 pagesEndroit: The Art of TravelingChristian GreerNo ratings yet

- Krystia Kim M. Orias, RRT: Career ObjectiveDocument4 pagesKrystia Kim M. Orias, RRT: Career ObjectiveKyla Pama100% (1)

- Luiz Otavio Barros: Teaching Spoken English at Advanced LevelDocument22 pagesLuiz Otavio Barros: Teaching Spoken English at Advanced LevelLuiz Otávio Barros, MA100% (1)

- Muñoz - Disidentifications - Queers of Color and The Performance of PoliticsDocument245 pagesMuñoz - Disidentifications - Queers of Color and The Performance of PoliticsMelissa Jaeger100% (2)

- Auditing Overview PowerpointDocument15 pagesAuditing Overview PowerpointJayNo ratings yet

- Besiness Management ExamDocument7 pagesBesiness Management ExamBrenda HarveyNo ratings yet

- Mory 2016Document35 pagesMory 2016daniela fonnegraNo ratings yet

- Customer EvaluationDocument20 pagesCustomer EvaluationAlma Mae BetonioNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Neuropsychology of Dreaming: Insights Into The Neural Basis of Dreaming With New Techniques of Sleep Recording and Analysis.Document41 pagesBeyond The Neuropsychology of Dreaming: Insights Into The Neural Basis of Dreaming With New Techniques of Sleep Recording and Analysis.albertoadalidNo ratings yet

- A Thousand Years of Good Prayers Dialectical JournalDocument2 pagesA Thousand Years of Good Prayers Dialectical Journalapi-327824054No ratings yet

- I. Multiple ChoiceDocument2 pagesI. Multiple ChoiceZynlt PhamNo ratings yet

- Management Process and Organization Behavior (MPOB) Solved MCQs (Set-2)Document8 pagesManagement Process and Organization Behavior (MPOB) Solved MCQs (Set-2)Rajeev TripathiNo ratings yet

- The Recruitment, Selection and Training of People at Arcadia An Arcadia Case StudyDocument12 pagesThe Recruitment, Selection and Training of People at Arcadia An Arcadia Case StudyVinodNKumarNo ratings yet

- Moral IntuitionismDocument24 pagesMoral IntuitionismAshjasheen JamenourNo ratings yet