Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Budget Line

Uploaded by

aytennuraiyevaaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Budget Line

Uploaded by

aytennuraiyevaaCopyright:

Available Formats

What I want to do in this video is introduce you to the idea of a budget line.

Actually, probably isn't a

new idea. It's a derivative idea of what you've seen and often in an introductory algebra course where A,

you've gotten a certain amount of money and you can spend it on a certain combination of goods. What

are all the different possibilities that you can actually buy? That's really what a budget line is. Let's say

that you have an income and I'll do it both in the abstract and the concrete. I'll do it variables and then

I'll also do it with actual numbers. Lets say your income, your income in a month is Y and lets say that

you spend all of your money. Your income is equal to you expenditures. Assuming in our little model

here that you're not going to be saving any money. To show how overly simplified we can make a model

we are going to only assume that you can spend on two different goods and that's so that we can

actually plot all the combinations on a two dimensional surface like the screen over here. Obviously,

most people buy many more or they at least are choosing between many, many more than two goods.

But let's say you can choose between 2 goods and let's just take goods that we've been doing using in

recent videos. That 2 goods that you buy are either chocolate or fruit. You could buy chocolate by the

bar or fruit by the pound. What are going to be your expenditures assuming you spend it all on

chocolate and fruit? Well, there's going to be the amount that you spend on chocolate will be the price

of chocolate times the quantity of chocolate you buy which is the number of bars. And then the amount

you spent on fruit will be the price of fruit per pound times the quantity of fruit. For example, if Y = $20

a month and the price, actually we'll plot this in a second, the price of chocolate is equal to $1 per bar

and the price of fruit is equal to $2 per pound. I think these were the prices I used in a per pound of

fruit. Then all of a sudden, you would know what this is, you would know what this is and this is. You

know what the Ps are and the Y and then you could actually graph one of these quantities relative to the

other. What we can do is, and let's do that, we can graph the quantity of 1 relative to the other. Why

don't we put the quantity of chocolate on this axis over here and let's put the quantity of fruit on this

axis over here. First, if we wanted to graph it I like to put it, since I've put quantity of chocolate on the

vertical axis here, I'd like to solve this equation for quantity of chocolate as a function of quantity fruit

and it should make it pretty straight forward to graph. Let's try that out. First, I'm just going to rewrite

this without expenditures in between. We have our income, our income Y = price of chocolate times the

quantity of chocolate plus the price of fruit times the quantity of fruit. Now, I want to solve for the

quantity of chocolate. Let me make that orange so we know that this is this one right over here. If I want

to solve for that, the best way I could isolate it one side of this equation. Let me get rid of this this

yellow part right over here and the best way to do that is to subtract it from both sides. Let's subtract

the price of fruit times the quantity of fruit and I could substitute the numbers in first and that might

actually make it a little bit easier to understand but I like to keep it general first. You see, you don't have

to just use with these numbers you could just see the general result here. I'm going to subtract it from

the left hand side and the right hand side and the whole point is to get rid of it from the right hand side.

This cancels out, the left hand side becomes your income minus the price of fruit times the quantity of

fruit. This is going to be equal to your right hand side which is just the price of chocolate times the

quantity of chocolate. Now if we want to solve for the quantity of chocolate we just divide both sides by

the price of chocolate and then you get it, and I'll flip the sides. You get the quantity of chocolates, is

going to be equal to your income, your income divided by the price of chocolate minus the price of fruit

times the quantity of fruit all of that over the price of chocolate. All over that over the price of

chocolate. We can actually substitute these numbers in here and then we can actually plot what

essentially this budget line will look like. In our situation, 20, Y = 20, the price of chocolate is equal to 1.

Price of chocolate is equal to 1. This term right over here, $20 per month divided by $1 per bar which

would actually give you 20 bars per month if you work out the units. This term right over here just

simplifies to 20. This is actually an interesting term, your income, your income in dollars divided by the

price of an actual good or service. You could view this term right over here as your real income. The

reason why it's called real income is it's actually pegging what your earnings to what you can buy. It's

pegging it to a certain real goods, it's not tied to some abstract quantity like money which always has a

changing buying power. What you could buy for $20 in 2010 is very different than what you could buy

for $20 in 1940. Here, when you divide your income, divide it a by a price of some good it's really telling

you your income in terms of that good. You could view your income as $20 per month or you could view

your income if you wanted your income in chocolate bars. You could say my income is, I could buy 20

chocolate bars each month. So I could say, my income 20 chocolate bars per month. They would be

equivalent to you assuming that you could sell the chocolate bars for the same price you could buy it

and that's somewhat of an assumption. But you could say I have the equivalent income of 20 bars a

month. You could have also done it in fruit. I have the equivalent income of 20 divided by 2, 10 pounds

of fruit a month. It's trying your income to real things, not the abstract quantity like money. Anyway, this

is going to be equal to, let me write it over here. My quantity of chocolate is going to be equal to this

term right over here as 20. If you wanted to do the units, it would be 20 bars per month and you could

do a little bit of dimensional analysis to come up with that. You could treat the units just like numbers

and see how the cancel out. 20 bars per month minus the price of fruit divided by the price of chocolate.

$2 per pound of fruit. The price of fruit is going to be $2 and I actually want to look at the units because

that's interesting. Let me write it here. The price of fruit is equal to $2 per pound. Let me write it this

way. $2 per pound of fruit, I'll show you how the units cancel out. Then we're dividing that by the price

of chocolate. Dividing it by the price of chocolate which is equal to $1 per bar of chocolate. Now,

obviously the math is fairly straight forward. We just get 2, but the units are a little bit interesting. You

have a dollar and the numerator of the numerator and a dollar, the numerator of the denominator,

those will cancel out. You could actually view this as, this is going to be the same thing just to look at the

units. This is going to be, this is the same thing as the numerator times the inverse times the reciprocal

of the denominator right over here. You could say $2 per pound times, the reciprocal of 1 is just 1, times

1 bar per dollar. Then the dollars cancel out and you are left with 2 bars per pound of fruit. What we've

actually done over here, this term right over here, it gives us bars of chocolate per pound of fruit. It

simplifies to 2 bars of chocolate per pound of fruit. It's actually giving you the opportunity cost of a

pound of fruit. It's saying hey, you could buy a pound of fruit but you'd be giving up 2 bars of chocolate.

Because the price, you could get 2 bars of chocolate for every pound of fruit. You could view this as the

relative price, this right over here is the relative price of fruit in this example. It's telling you the

opportunity cost, it's telling you how much fruit cost in terms of chocolate bars. Regardless, that number

is fairly straight forward, it was just a 2. Minus 2 times the quantity of fruit. This is fairly straight forward

to plot. If the quantity of fruit it 0, our quantity of chocolate is 20. This is going to be 20 over here. This is

20 and this is going to be 10. This is 15, this is 5. This is a point on our budget line right over there. There

is multiple ways that you could think about this. One way you could say is if you buy no chocolate, if the

quantity of chocolate is 0, what is going to be the quantity of fruit? Then you could solve this or you

could just say, "Look, if I have $20 a month" then I'm going to spend it all on fruit. "I can buy 10 pounds

of fruit." So to say that this right over here is 10. Let's say this right over here is 10, this is 5, so this is

also on our budget line and every point in between is going to be on our budget line. Every point in

between is going to be on our budget line. Another way you could have done this and this comes

straight out of kind of your typical algebra 1 course. You could say, in this case, if you view this as the Y

axis, you say your Y interceptor, you say, "My chocolate quantity interceptor is 20" and then my slop is

negative 2. "My slope is negative 2." For every extra pound of fruit I buy I have to give up 2 pounds of

chocolate. You could also view this as the opportunity cost of fruit. You see this slope as we go forward,

if we buy one more pound quantity of fruit we're giving up 2 bars of chocolate. One statement I did just

make, I said every point on this line is a possibility and I can only say that if we assume that both of

these goods are divisible goods which means we can buy arbitrarily small amounts of it, that we could

buy 10th of a bar of chocolate on average especially. Or we could buy 100th of a pound of fruit. If they

weren't divisible, they're indivisible then only the whole quantities would be the possibility points. We'll

just assume they're divisible, especially even if the store only sells indivisible bars of chocolate. If you

buy one bar of chocolate every 4 months, on average you're buying .25 bars of chocolate per month.

Even that, on average, almost anything, almost anything here is divisible. This line right over here shows

all of the combinations we can buy. All of the combinations of the divisible goods we could buy if we

spend all of our money. That right over there is our budget line. That is our budget line. That is our

budget line. And any combination out here is unaffordable. We don't have enough money for that. Any

combination down here is affordable. Actually, we would end up with extra money if we're below the

budget line. This isn't all that different than what we saw with the production possibilities frontier.

Remember, we had a curve that really showed all of the if we were producing 2 goods, what

combinations of goods we could produce. Anything on that curve for the productions possibility frontier

was efficient. Anything outside of it was unattainable and anything inside was attainable but inefficient.

The slope of the budget line is a crucial concept in microeconomics. It represents the rate at which a

consumer can trade one good for another while maintaining the same level of utility. The slope of the

budget line is determined by the relative prices of the two goods and the consumer's income.

A steep slope indicates that the price of one good is relatively high compared to the other, while a

shallow slope indicates that the price of one good is relatively low compared to the other. The slope of

the budget line also determines the consumer's optimal consumption bundle, which is the combination

of goods that maximizes their utility subject to their budget constraint.

A change in the relative price of the two goods will cause the budget line to rotate around the intercept

on the y-axis, changing the slope and the optimal consumption bundle.

A change in income will cause the budget line to shift parallel to itself, changing the intercepts on both

axes but not the slope or the optimal consumption bundle.

You might also like

- Day 6 - Exponential Growth and DecayDocument4 pagesDay 6 - Exponential Growth and DecayBeverly AlonNo ratings yet

- The Coupon Master's Guide to using Extreme Coupons to save Extreme MoneyFrom EverandThe Coupon Master's Guide to using Extreme Coupons to save Extreme MoneyNo ratings yet

- Summary Derivation of The Demand CurveDocument8 pagesSummary Derivation of The Demand CurveFerrel Infante AcuñaNo ratings yet

- What To Do With MoneyDocument50 pagesWhat To Do With MoneyAllisonNo ratings yet

- J HEPQp SKDBGDocument23 pagesJ HEPQp SKDBGLucifer MorningstarNo ratings yet

- I Saved 92% on My Groceries! A Guide To Getting the Best Deals & FreebiesFrom EverandI Saved 92% on My Groceries! A Guide To Getting the Best Deals & FreebiesNo ratings yet

- SpendDocument127 pagesSpendJohn Wang100% (1)

- Money Management Strategies Learn Personal Finance To Manage Compulsive Your Spending, Savings And Live A Debt Free LifestyleFrom EverandMoney Management Strategies Learn Personal Finance To Manage Compulsive Your Spending, Savings And Live A Debt Free LifestyleNo ratings yet

- Budget LineDocument7 pagesBudget LineArbie MoralesNo ratings yet

- Grocery Couponing Secrets: How To Save Money on GroceriesFrom EverandGrocery Couponing Secrets: How To Save Money on GroceriesRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Calculate Signage CorrectlyDocument10 pagesCalculate Signage Correctlybluerider1No ratings yet

- Read This if You're Tired Of Being Broke - A Guide to Making Money on the InternetFrom EverandRead This if You're Tired Of Being Broke - A Guide to Making Money on the InternetRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Money Matters: A Simple Guide To Help You Make Ends MeetFrom EverandMoney Matters: A Simple Guide To Help You Make Ends MeetNo ratings yet

- The Most Effective Method To Save $100,000 in 15 YearsFrom EverandThe Most Effective Method To Save $100,000 in 15 YearsNo ratings yet

- Your Wealth is Your Choice: You Have More Control Than You Think: Financial Freedom, #190From EverandYour Wealth is Your Choice: You Have More Control Than You Think: Financial Freedom, #190No ratings yet

- 5 XT0 MZL 72 EDocument20 pages5 XT0 MZL 72 EMunibaNo ratings yet

- Saving for a House Down Payment #1: Single Person, Small City: Financial Freedom, #25From EverandSaving for a House Down Payment #1: Single Person, Small City: Financial Freedom, #25No ratings yet

- Bonanza Bits: Discovering the Mother Lode of Everyday SavingsFrom EverandBonanza Bits: Discovering the Mother Lode of Everyday SavingsNo ratings yet

- The 21 Day Budgeting Challenge: Learn How to Set up a Budget, Pay of Debts and Make the Most of Your MoneyFrom EverandThe 21 Day Budgeting Challenge: Learn How to Set up a Budget, Pay of Debts and Make the Most of Your MoneyNo ratings yet

- CPE196 Powerpoint 4Document4 pagesCPE196 Powerpoint 4armonkNo ratings yet

- Qa 40Document16 pagesQa 40ambrosialnectarNo ratings yet

- Frugal Living: How to Save Money and Live More with LessFrom EverandFrugal Living: How to Save Money and Live More with LessRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Your Money or Your Life (Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez)Document7 pagesYour Money or Your Life (Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez)homo.ingratusNo ratings yet

- Life Can't Throw A Fast Ball: A Guide to Personal FinanceFrom EverandLife Can't Throw A Fast Ball: A Guide to Personal FinanceNo ratings yet

- How to Use a Daily Budget: The Perfect Best Way to Curb Your Spending: Financial Freedom, #158From EverandHow to Use a Daily Budget: The Perfect Best Way to Curb Your Spending: Financial Freedom, #158No ratings yet

- How To Make A Ton Of Money Selling The Things You Own And Do Not Need; A guide through eBay, Craigslist, Facebook, flea markets, yard sales, and swap meetsFrom EverandHow To Make A Ton Of Money Selling The Things You Own And Do Not Need; A guide through eBay, Craigslist, Facebook, flea markets, yard sales, and swap meetsNo ratings yet

- Two People, One Budget: Create a Budget and Start Income Investing: Financial Freedom, #94From EverandTwo People, One Budget: Create a Budget and Start Income Investing: Financial Freedom, #94No ratings yet

- Memoirs of a Side Hustler: Five Principles to Run a Side Business SuccessfullyFrom EverandMemoirs of a Side Hustler: Five Principles to Run a Side Business SuccessfullyNo ratings yet

- My Military Brokeassness: A book on Finance Written by a Broke Ass E-5From EverandMy Military Brokeassness: A book on Finance Written by a Broke Ass E-5No ratings yet

- Business Math Term 2Document26 pagesBusiness Math Term 2Andrei Stalin LaxaNo ratings yet

- Extreme Couponing for Busy Women: A Busy Woman's Guide to Extreme CouponingFrom EverandExtreme Couponing for Busy Women: A Busy Woman's Guide to Extreme CouponingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Motley Fool 10 Steps To Financial Freedom PDFDocument33 pagesThe Motley Fool 10 Steps To Financial Freedom PDFMitesh Take100% (3)

- Money Hacks: 275+ Ways to Decrease Spending, Increase Savings, and Make Your Money Work for You!From EverandMoney Hacks: 275+ Ways to Decrease Spending, Increase Savings, and Make Your Money Work for You!Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Calculating Free Energies Using Adaptive Biasing Force MethodDocument14 pagesCalculating Free Energies Using Adaptive Biasing Force MethodAmin SagarNo ratings yet

- Hofstede's Cultural DimensionsDocument35 pagesHofstede's Cultural DimensionsAALIYA NASHATNo ratings yet

- WWW Ranker Com List Best-Isekai-Manga-Recommendations Ranker-AnimeDocument8 pagesWWW Ranker Com List Best-Isekai-Manga-Recommendations Ranker-AnimeDestiny EasonNo ratings yet

- 11-Rubber & PlasticsDocument48 pages11-Rubber & PlasticsJack NgNo ratings yet

- 5.1 Behaviour of Water in Rocks and SoilsDocument5 pages5.1 Behaviour of Water in Rocks and SoilsHernandez, Mark Jyssie M.No ratings yet

- TM Mic Opmaint EngDocument186 pagesTM Mic Opmaint Engkisedi2001100% (2)

- .IAF-GD5-2006 Guide 65 Issue 3Document30 pages.IAF-GD5-2006 Guide 65 Issue 3bg_phoenixNo ratings yet

- Governance Operating Model: Structure Oversight Responsibilities Talent and Culture Infrastructu REDocument6 pagesGovernance Operating Model: Structure Oversight Responsibilities Talent and Culture Infrastructu REBob SolísNo ratings yet

- Taylor Series PDFDocument147 pagesTaylor Series PDFDean HaynesNo ratings yet

- Electronic Diversity Visa ProgrambDocument1 pageElectronic Diversity Visa Programbsamkimari5No ratings yet

- Daftar ObatDocument18 pagesDaftar Obatyuyun hanakoNo ratings yet

- CIPD L5 EML LOL Wk3 v1.1Document19 pagesCIPD L5 EML LOL Wk3 v1.1JulianNo ratings yet

- Banking Ombudsman 58Document4 pagesBanking Ombudsman 58Sahil GauravNo ratings yet

- Rankine-Froude Model: Blade Element Momentum Theory Is A Theory That Combines BothDocument111 pagesRankine-Froude Model: Blade Element Momentum Theory Is A Theory That Combines BothphysicsNo ratings yet

- Trucks Part NumbersDocument51 pagesTrucks Part NumbersBadia MudhishNo ratings yet

- Management PriniciplesDocument87 pagesManagement Priniciplesbusyboy_spNo ratings yet

- Installation Instructions INI Luma Gen2Document21 pagesInstallation Instructions INI Luma Gen2John Kim CarandangNo ratings yet

- TTDM - JithinDocument24 pagesTTDM - JithinAditya jainNo ratings yet

- Logistic RegressionDocument7 pagesLogistic RegressionShashank JainNo ratings yet

- Topic: Grammatical Issues: What Are Parts of Speech?Document122 pagesTopic: Grammatical Issues: What Are Parts of Speech?AK AKASHNo ratings yet

- IJRHAL - Exploring The Journey of Steel Authority of India (SAIL) As A Maharatna CompanyDocument12 pagesIJRHAL - Exploring The Journey of Steel Authority of India (SAIL) As A Maharatna CompanyImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 AssignmentDocument2 pagesChapter 11 AssignmentsainothegamerNo ratings yet

- Statistical Process Control and Process Capability PPT EXPLANATIONDocument2 pagesStatistical Process Control and Process Capability PPT EXPLANATIONJohn Carlo SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Class 12 Physics Derivations Shobhit NirwanDocument6 pagesClass 12 Physics Derivations Shobhit Nirwanaastha.sawlaniNo ratings yet

- Ethernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application TechniqueDocument50 pagesEthernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application Techniquegnazareth_No ratings yet

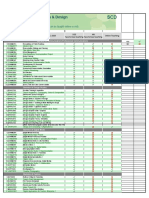

- SCD Course List in Sem 2.2020 (FTF or Online) (Updated 02 July 2020)Document2 pagesSCD Course List in Sem 2.2020 (FTF or Online) (Updated 02 July 2020)Nguyễn Hồng AnhNo ratings yet

- D E S C R I P T I O N: Acknowledgement Receipt For EquipmentDocument2 pagesD E S C R I P T I O N: Acknowledgement Receipt For EquipmentTindusNiobetoNo ratings yet

- Community Profile and Baseline DataDocument7 pagesCommunity Profile and Baseline DataEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Man Bni PNT XXX 105 Z015 I17 Dok 886160 03 000Document36 pagesMan Bni PNT XXX 105 Z015 I17 Dok 886160 03 000Eozz JaorNo ratings yet

- Concrete Pumping.: Squeeze PumpsDocument2 pagesConcrete Pumping.: Squeeze PumpsALINDA BRIANNo ratings yet