Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chandler Stategy and Structure Summary-With-Cover-Page-V2

Uploaded by

1823665cOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chandler Stategy and Structure Summary-With-Cover-Page-V2

Uploaded by

1823665cCopyright:

Available Formats

Accelerat ing t he world's research.

A summary of STRATEGY AND

STRUCTURE: CHAPTERS IN THE

HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL

EMPIRE by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr.

Vikas N Prabhu

Related papers Download a PDF Pack of t he best relat ed papers

T he evOluT IOn Of enTerprIse OrganIzaT IOn DesIgns

Treey Marfu'ah

Organ, Organism, Organizat ion: A St udy in t he Evolut ion of t he Organismic Met aphor

Vikas N Prabhu

T he mult idivisional st ruct ure: Organizat ional fossil or source of value?

Robert Hoskisson, Hicheon Kim

A summary of

STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE: CHAPTERS IN THE HISTORY OF THE INDUSTRIAL EMPIRE

By Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. (1962: The M.I.T Press; 1982 reprint.)

Precursor:

The precursor to Chandler’s work was the trend in comparative business history where a study of

activity breadth (i.e. investigating many firms doing one activity) was considered as important as

studying organizational breadth (i.e. one firm doing all activities). One of the activities that gained

focus was ‘Business Administration’, especially due to expansion of American economy post WW2.

• Chandler’s own research showed emergence of multi-divisional type of organization,

especially amongst the topmost firms. Chandler advocated decentralized strategy working

through the “visible hand of the management” (The Economist, 2009)

• Du Pont, GM, Jersey Standard and Sears were the amongst the first to initiate major

reorganizations, and the “executives of these four began to develop their new structure

independently of each other and of any other firm. There was no imitation.” (p. 3)

Method:

In order to accomplish a comprehensive investigation, Chandler asserts a deep understanding of the

following is needed:

1. Administrative history of the firm

2. Growth trajectory of the firm

3. History of change in American economy

4. State of the field (in USA)

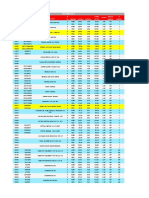

A sample of about 70 companies (listed in Table 2, p. 6) were studied, in addition to the initial survey

that was done on 50 largest industries of 1909 (listed in Table 1, p. 5). This large sample helped to

study, in addition to the 4 key companies, the “history of business administration in the United

States and changes in the larger American economy.” (p. 4)

Core concepts used:

• Industrial enterprise: “large private, profit-oriented business firm involved in the handling of

goods in some or all of the successive industrial processes from procurement of the raw

material to the sale to the ultimate consumer” (p. 8)

• Administration: high-level supervisory functions of coordinate, appraise, and plan performed

by executives; executed through a hierarchy that may involve several managerial levels, down

to the agents who directly accomplish the various organizational tasks

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 1 of 9

• Strategic and Tactical decisions: The former is concerned with long-term health of the

enterprise while the latter concerns day-to-day operational decisions

Basic propositions made:

1. Administration is an identifiable activity that has specifically defined tasks which are different

from functional work. Especially in a large firm, this is a specialized task performed by a

dedicated team that does not involve in functional details

2. Administrator ought to handle to types of tasks:

a. Those concerned with long-term planning and appraisal

b. Those needed to meet immediate problems, handling contingencies/crises

3. Executives work in a hierarchy following different levels of authority, (see Chart I, p. 10) which

consist of:

a. The general office concerned with firm-level goals, policies

b. The divisional central office which is fairly self-contained in its resources, covering a

product-line or geographical region, and administers a number of departments

c. The departmental headquarters that supervises field units

d. The lowest-level of field units that execute the functional tasks

e. In the above hierarchy, upper levels perform strategic decisions while lower levels

invest in tactical decisions. The flow of authority is top-down: ones at the top are

entrepreneurial, and the intermediate decision makers are managers.

W.r.t above, Chandler lays down the “core competency” for an effective entrepreneur (p.12)

Conception of Strategy and Structure:

Having observed that variety of roles and levels in an administrative setup, Chandler deems his most

important thesis, “different organizational forms result from different types of growth can be stated

more precisely if the planning and carrying out of such growth is considered strategy, and the

organization devised to administer these enlarged activities and resources, a structure.” (p. 13)

Adoption of a new strategy entails adding new resources, and “alters the business horizons of the

men responsible for the enterprise” (p.13). In response to the new awareness created by the

opportunities (for growth or change), the organization ought to refashion its structure – either by

redeploying existing or expanding resources – to operate at the newly desired efficiency levels. If

the growth is not complemented by corresponding structural adjustment, the result will be

inefficiency. (p.16)

Historical Setting: The lead up to the ‘managerial revolution’ (The Visible Hand, 1977)

Phase 0: Prior to 1850, the American business scenario consisted of very small industries that were

directly managed and administered by individuals or familial groups and, hence, rarely needed

administrative focus/expertise. The owners divested themselves in functional activities and there

was no need to engage in long-term planning.

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 2 of 9

Phase 1: Around this time, two business owners are highlighted as being the pioneers of starting

(nascent) administrative structures within the business setting: John Jacob Astor’s American Fur

Company (which created Northern and Western departments to manage fur trapping and sourcing)

and Nicholas Biddle’ Second Bank (whose organization had a divisional structure and incorporated

a detailed system of reporting). However, the foundation stone to formal business administration

was laid by the railroad construction which had as much significant administrative impact as it was

strategic: “its operation called for more administration than its construction” (p.21). Its formalization

was still embryonic as the diversity of operations was still limited.

Daniel McCallum, superintendent of Erie, who created organizational charts showing flows of

authority and reporting, affirms the need for the administrative setting when he comments that “…

Any system which might be applicable to the business and extent of a short road would be found

entirely inadequate to the wants of a long one…” (p.22). Railroads were the precedent for the

growth of the great industrial enterprise (see p.23). Rapid growth of urban market, coupled with

enhanced connectivity, demanded higher industrial outputs and, hence, strategies of geographical

dispersion and vertical integration took hold (p.24)

In the last decades of 1800’s, which heralded great material prosperity, the focus of business owners

was looking for efficient administrative structures to manage their newly created business empires.

Phase 2: Industrial expansion demanded taking on new functions. Here the story of Gustavus Swift

gives a succinct narrative of the evolution towards higher integration and consolidation of diverse

activities within the scope of one administrative enterprise (see p. 25-26). The vast resources

accumulated through the above strategy enabled these enterprises to diversify into related

markets/products as well as venture into secondary products that could “piggyback” upon the

existing structure and functions. The far markets were managed through subsidiaries. The Singer

sewing machine story gives an excellent example of marketing integration (see p.28)

Phase 2.5: In combination with vertical integration, there were also horizontal combinations of

producers/manufacturers – into trusts/federations – to combat the threat of excess capacity and

market glut. The New Jersey amendment (1889) facilitated joint incorporation, paving the way for

one company to hold stocks in another, thus, enabling legally controlled consolidation. (see p.31).

This phase, by consolidating loose alliances into tightly bound entities, greatly enabled economies

of scale and focused technological innovation. (p.31), which in turn enhanced the need for more

vertical integration. The story of National Biscuit (p.32-33) provides an excellent example.

Phase 3: The administration of the integrated enterprise was rendered inefficient due to lack of a

robust structure: its channels of authority remained unclear and the levels of integration tended

towards more centralized control. This was largely inefficient given the complex load of planning

and coordination for all units that was placed upon the headquarters (p.41). The multidivisional

decentralized structure emerged in the early part of 20th century to manage and coordinate the

operational and entrepreneurial complexity of the steadily growing and diversifying organization

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 3 of 9

(see p.44). The changing environment of WWII gave impetus upon businesses to adapt and diversify

and that, in turn, emphasized the need for multidivisional structure. The four case-studies of the

book – du Pont, General Motors, Standard Oil, and Sears – are seen to be exemplars in having

transformed into the multidivisional structure and, hence, merit deeper study.

The case studies serve to affirm Chandler’s thesis of highlighting that structure follows strategy,

which he asserts by stressing upon multidivisional structure if firms have to (strategically) succeed

in the increasingly diverse and complex marketplace of the modern world (p.49)

The Case Studies

Case-study #1: du Pont

Historical Context: Around 1902, after a century of operations, the du Pont company was unclear

of its future. The older board members were in favour of a sell-off when Alfred du Pont offered to

buy it all (saving his “birthright” (p.52)). Once acquired, with the help of partners Coleman and

Pierre, the trio set out on an exercise to consolidate and reorganize the facilities, personnel and

functions, as they aimed to eliminate duplication and achieve systematic supervision by functional

coordination (p.56). As a first step, they hired enterprising executives (Haskell and Barksdale) to

manage their dynamite works; which the executives organized and managed much on their own.

Inspired by its success, the board went ahead to imitate the same structure in other two divisions –

black powder and smokeless powder. The entire team then came together in a centralized office

and assigned clearly defined roles splitting all administrative activities amongst themselves (see

p.57)

Strategic Drivers: consolidation of various units acquired over a period of time; manufacturing units

of different but related products

Initial Structural Modifications:

• Differentiated between entrepreneurial (President and VP) and operational (Director) tasks

• Line and staff level demarcation in communication and supervision of functions

• Organization of core functional departments: manufacturing (operations) and sales; and

non-core: Essential materials, development, real estate, legal, and treasury

• Appointment of roles was not inheritance driven (p.64)

The structural modifications took du Pont from being a family firm to a professional manned

enterprise (see Chart 2, p.62). The first phase of centralization (upto 1919) impressed upon

individual responsibility for operational matters, while the Executive Committee focused on broad

goals and policies, with focus on company as a whole. The financial analysis witnessed an increased

usage of statistical data and forecasting methods (by Donaldson Brown).

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 4 of 9

Further centralization was driven by Haskell’s subcommittee report in 1919 which advocated a

functionally departmentalized structure aimed at maximum output with minimum effort. It aimed

towards coordinating functions (set of like activities) rather than like things (products). It involved

grouping broad functional activities into separate administrative units and placing it under individual

authority with undivided authority. (See charts in p.74 and 75). However, this model failed when

the strategy of diversification took over as a response to the threat of excess capacity due to

cancellation of government orders (1908) and end of the war.

Strategy of diversification intensified with forays into artificial leather (owing to common

technological expertise), pyroxylin (owing to ease of coordination), dyes (owing to market demand)

and varnish (owing to similar skills and machinery), finally culminating in a broad-based

diversification strategy that aimed at utilizing all of du Pont facilities (see p.89). The new strategy

created an experience mismatch within the organization, which led to confusions at the central

office (in matters of goal determination, resource allocation and appraisal), and also led to

inefficient planning due to unavailability of statistical data on the new products.

A new structure, which was product-based, was suggested to deal with the new administrative

needs (see Chart 4, p.97) wherein a common executive was responsible and accountable for all

functions along with profit and performance. Adoption of the multidivisional structure faced initial

resistance due to older executives (like president Irenee) who were conditioned by training and

experience to believe in the efficacy of the existing structure, and, hence, sought to defend it. The

younger executives attempted to “squeeze in” the new structure through proposing and

experimenting with ‘industry councils’ (see p.102) which worked very well. However, with post-war

recession pushing du Pont into losses on every product, the administrators were forced to adopt a

full-fledged multidivisional structure as shown in Chart 5 in p.108-109. The structure ensured that

senior executive at the general office focused on strategic decisions and entrepreneurial activities,

while the divisional managers had full authority and facilities to make their day-to-day tactical

decisions.

Case-study #2: General Motors

Historical Context: William Durant, who started as a small-time entrepreneur selling carts and

carriages in 1885, struck gold with acquiring the Buick car company. As Durant’s fortunes rose, so

did his ambitions and he pursued an aggressive course of volume production and vertical

integration, being focused exclusively on sales and marketing while leaving the centralized

administrative responsibilities to his colleagues. By 1908, predicting a sale of 500,000 cars per year,

Durant began combining various facilities and also acquiring small manufactures and created

General Motors, which was, then, just a holding company. In this pursuit of integration for

capacity/volumes, Durant failed on two counts: he did not prepare for demand dips and failed to

build sufficient cash backup; and, gave no thought to building an organizational structure that would

deliver benefits of scale and coordination.

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 5 of 9

The first attempt at structuring happened in the recession of 1910 when the bankers took over the

struggling company and, under the leadership of James Storrow, attempted to place all GM activities

under a centralized structure that demanded cooperation between and control over the

autonomous subsidiaries. A board of managers was setup to determine broad policy and conduct

appraisals. Three permanent offices – purchasing, accounting, and production – were setup for

overall administration. However, in a few years, this attempt failed due to the resistance on the part

of the subsidiaries who perceived an interference in their hitherto independent working style.

Subsequently, Durant returned back to the helm and continued his pursuit for volumes. Meanwhile,

GM was transformed from a holding company to an operating company which, legally had a

multidivisional structure but, in reality, had units that were loosely coupled. As a result, the relations

between the operating divisions became more haphazard and less coordinated. The du Ponts, who

held the say in GM at this point, took up the task to bring in centralized control. Their attempt, which

involved creation of top-level committees that oversaw autonomous divisions, may have worked at

du Pont company but did not do much impact at GM which continue to be an “expanding

agglomeration of different companies.” (p.127)

The pursuit of volumes coupled with lack of coordination led to a great accumulation of inventory

which, due to drop of sales in the post-war recession, led to a dead-loss of $84M for GM. This is the

point the du Ponts take over, Durant quit, and the extensively researched and well-elaborated

organizational structure of Alfred Sloan, who was then the President of a GM subsidiary.

The Sloan Structure:

• General office (“central organization”) consisting of general offices and staff executives

• Clearly defined lines of authority and communication between office and divisions

• Accurate and useful data-flow along the above lines

• General officers supervise and coordinate group of divisions and help to make policy for the

organization as a whole

• Staff executives to advise all heads and provide information necessary for appraisals

Sloan believed divisional independence fostered initiate and innovation and, hence, he permitted

the general executives only an advisory role and no role authority. (see p. 134-135; Chart 6, p.136)

In the process of implementing Sloan’s structure, the administration took the pragmatic approach

of defining divisional boundaries that created an array of automobiles (Cadillac – Buick – Oakland –

Oldsmobile – Pontiac – Chevrolet) which involved a comprehensive market strategy. Along with this,

refinements such as development of accurate data-tracking on costs, production, income, etc. were

brought in which, on the one hand, helped to conduct precise appraisal of divisions aimed at

maintaining strict administrative surveillance on divisions, while, on the other, enabled systematic

allocation of capital and other resources.

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 6 of 9

Case-study #3: Standard Oil Company (New Jersey)

Historical Context: Jersey oil grew tremendously (assets rose by a billion dollars) in the period 1912

to 1925. During these growing years, the Board of Directors tended to increase administrative

control over single-function department (called subsidiaries) when compared to integrated

multifunction affiliates (p.166). The central office received reports but had minimal discretion in

allocation of funds or recourses. There was no auxiliary or staff functions at the head office. The

refining unit, in particular, was administered centrally effectively in a federated fashion (i.e. each

subsidiary had an executive in the headquarters and all these executives would frequently meet in

“The Room” (p.169) to discuss and coordinate decisions). The addition of new oil fields from Texas

and California revolutionized supply and forced the company to expand its operations through

augmentation of equipment, plant, and personnel. There was a need for increased specialization

and creation of new service and auxiliary departments. The expansion led to purchase of new

affiliates which led to a range of administrative problems.

Strategic Drivers: backward integration to cater to rapidly growing market (and ready customers);

acquisition of new properties that needed administrative support; need for an explicit strategy and

definite structure of production activities in order to meet competition; rapid expansion of

transportation facilities along with production activities.

The structural organization at Jersey oil was not a formalized or rational attempt, rather a series of

responses to needs created by expansion and vertical integration. “By the mid-1920s, Jersey oil had

moved well along the road to a better balance of functions.” (p.175) However, the growth led to

administrative confusion and difficulties as the lines of authority and communication were never

distinctly drawn. Administrative responses, as below, acted as stepping stones towards a gradual

foundation of administrative structure:

• Demand for gasoline prompted formation of Development Department

• In 1920s, domestic marketeers began to pay attention to advertising and, much later,

formed additional staff offices to analyse market performance

• A board of functional specialists was setup

In 1924, the board began to focus on improving the organization and coordination of manufacturing

committee, which was the most important functional administrative unit. Lack of organization had

led to duplication of effort, inadequate usage of staff departments, delay in reaching group decisions

and needless executive time spent on operating routines. (see p.182) Even allocation of crude oil,

assignment of transportation, and distribution of refined products were getting complicated and a

structure was needed to establish control (p.184). By 1925, decisions regarding structural

reorganization began to be effected:

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 7 of 9

• Setting up the coordination department and committee to look at overall planning and

appraisal (see p.190) which greatly helped in mobilizing Jersey’s resources

• Setting up of budget department and committee to provide data essential to more

systematic and rational forward planning and other overall entrepreneurial activities

• Reorganizing of the marketing department wherein old heads were replaced with the

aggressive young ones to address the new demands of burgeoning gasoline market

• Reorganizing the manufacturing department with refashioned lines of authority and

communication aimed towards mitigating prevalent conflicts of attitudes and personalities

Despite these adjustments, the addition of oil fields in 1926 created a glut in the market, which

prompted Teagle to reformulate a ‘quasi-formal’ structuring plan in 1927. He observed that decision

making in the central office was getting slow and needed to be remedied. He wanted to remove

“group responsibility for administrative action. (p.210) Creating a multi-departmental structure was

the solution for it. (see p.216 for the final structure implemented)

Case-study #4: Sears, Roebuck and Company

Historical Context: Sears started as a mail-order catalogue targeting Rural America, especially the

farmers who would desire high-priced merchandise that would not be stocked in the rural-front

stores. In a matter of a decade, the business grew immensely – upto a hundred thousand orders a

day. Expansion encouraged vertical integration and the company often bought stake in the factories

that supplied their goods. Until 1921, Sears witness steady growth and profits. However, some

issues began to plague the company around this time:

• As business expanded, several departmental buying heads began operating independently.

Loose, informal and decentralized structure brought confusion and inefficiencies. Lack of

correlation led to errors in description. Suppliers were unable to distinguish between orders

• Merchandize department, which was supposed to oversee all buying, took little effort in

appraising the sub-departments

Furthermore, the recession of 1921 created inventory excesses and exposed administrative lapses

and lacunae. By 1924, Sears created a centralized functionally departmentalized structure for its

mail-order business in which the autonomy of the buyers was limited. Purchasing, sales promotion

and distribution were centralized at Chicago. However, in 1925, Sears top management perceived

another big threat to its business: popularization of the automobile which made the urban stores

accessible to the rural household. Sears served to counter this threat through the establishment of

retain stores (of three categories) which would tap the urban market – cheap suburban space with

ample parking, which would merchandize durable goods and cater to the mass buying customers.

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 8 of 9

The new strategy, however, faced severe strain due to inadept transition of back-office and

personnel from mail-order scheme to retailing scheme. The old staff were not geared for direct

confrontation with the customer. The Frazer committee was commissioned which suggested a two-

pronged hierarchical structure of functional and territorial units reporting into the President (see

Chart 8, p. 244). This system failed due to its essential weaknesses:

• Territorial and district managers were given wide responsibilities, often running conflict

• A reporting line was drawn from General Managers of mail order houses to the Territorial

Officer even though there was no direct contact between store managers and plant officers

in Chicago

The level of decentralized suggested by Frazer committee did not allow taking advantage of

managerial economies of scale. The structure also had a defect of store managers seeking help from

intermediate levels (local men) rather than reaching out to Chicago for assistance of many of their

problems. Moreover, the Territorial officers were taking on duties that belonged properly to the

functional departments. The core issue was that the above model was half-territorial and half-

functional. This had to be dismantled. The territorial units were transformed into multifunctional

divisions and the Chicago headquarters was rehashed as the general office. This new system had

the structure of a multi-divisional organization.

In the general office, the staff sections would provide advisory service and would assist the general

officers appraise performance, allocate funds, and formulate long-range policy (see Chart 9A, p.

273). The staff could not order, only advise, however they enjoyed auditory powers.

Submission by Vikas Prabhu, IIM, Bangalore | Page 9 of 9

You might also like

- A Summary of STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE CHAPDocument9 pagesA Summary of STRATEGY AND STRUCTURE CHAPPriyanka Mohanty (Ms)No ratings yet

- Teece, 2010 - Alfred Chandler and "Capabilities" Theories ofDocument20 pagesTeece, 2010 - Alfred Chandler and "Capabilities" Theories ofThalita BorgesNo ratings yet

- Armour and TeeceDocument18 pagesArmour and Teecea20236878No ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsFrom EverandCorporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Structure of Foreign and Nigerian FirmsDocument12 pagesStrategy and Structure of Foreign and Nigerian FirmsOly MiracleNo ratings yet

- The Twenty-First-Century Firm: Changing Economic Organization in International PerspectiveFrom EverandThe Twenty-First-Century Firm: Changing Economic Organization in International PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Hymer 1970 Efficiency of MNEDocument9 pagesHymer 1970 Efficiency of MNEhardyNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism Perspectives On AlfredDocument29 pagesThe Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism Perspectives On AlfredSujith GopinathanNo ratings yet

- Organizational Structure Changes in the Indian Cement IndustryDocument36 pagesOrganizational Structure Changes in the Indian Cement IndustryAdeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- Responsible Restructuring: Creative and Profitable Alternatives to LayoffsFrom EverandResponsible Restructuring: Creative and Profitable Alternatives to LayoffsNo ratings yet

- The Evolution and Restructuring of Diversified Business Groups in Emerging Markets: The Lessons From Chaebols in KoreaDocument24 pagesThe Evolution and Restructuring of Diversified Business Groups in Emerging Markets: The Lessons From Chaebols in KoreafalmendiNo ratings yet

- Growth Strategy in Small EntreprisesDocument79 pagesGrowth Strategy in Small EntreprisesDrBinay Kumar ShrivastavNo ratings yet

- Corporate Malaysia in Historical PerspectiveDocument36 pagesCorporate Malaysia in Historical Perspectivedaisuke_kazukiNo ratings yet

- UC Berkeley Previously Published WorksDocument56 pagesUC Berkeley Previously Published WorksBhushi ShushiNo ratings yet

- Table 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic ManagementDocument4 pagesTable 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic Managementanon_706827441No ratings yet

- StractureDocument41 pagesStracturepappujanNo ratings yet

- AEA: Multinational Corps May Not Be More Efficient Due to Imperfect MarketsDocument9 pagesAEA: Multinational Corps May Not Be More Efficient Due to Imperfect MarketsthaisribeiraNo ratings yet

- History and Contributors To The TheoryDocument8 pagesHistory and Contributors To The TheoryKapil AbrolNo ratings yet

- Introduction: An Overview of Telecommunication CompaniesDocument27 pagesIntroduction: An Overview of Telecommunication CompaniesSri VarshiniNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two 2020Document19 pagesChapter Two 2020Chuwanzi MbohNo ratings yet

- Chandler - Strategy and Structure Summ1Document6 pagesChandler - Strategy and Structure Summ1Kamran143No ratings yet

- Strategic Management in Non-ProfitsDocument17 pagesStrategic Management in Non-ProfitsMuhammad Imran SharifNo ratings yet

- 12 Chapter 5Document44 pages12 Chapter 5Tushar KapoorNo ratings yet

- The Organization of Economic Activity: The Information and Service Economy October 8, 2007 Bob Glushko and Anno SaxenianDocument36 pagesThe Organization of Economic Activity: The Information and Service Economy October 8, 2007 Bob Glushko and Anno Saxenianjanagyrama1No ratings yet

- Change Management ReportDocument19 pagesChange Management ReportalhumdulilahNo ratings yet

- Models of Public Administration Reform: "New Public Management (NPM) "Document8 pagesModels of Public Administration Reform: "New Public Management (NPM) "Nico Paolo Teruel100% (1)

- STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT-History and Development - WWW - VijaykumarbhatiaDocument18 pagesSTRATEGIC MANAGEMENT-History and Development - WWW - Vijaykumarbhatiasekhar_ntpcNo ratings yet

- Western and AFDocument27 pagesWestern and AFZ CNo ratings yet

- At Kearny Matrix ArticleDocument0 pagesAt Kearny Matrix ArticlejibharatNo ratings yet

- Evolution and Revolution As Organizations GrowDocument11 pagesEvolution and Revolution As Organizations GrowDenisse GarzaNo ratings yet

- Essay Strategic Practice 2019/2020 María Ruiz Marín KarlshochschuleDocument14 pagesEssay Strategic Practice 2019/2020 María Ruiz Marín KarlshochschulemariarmNo ratings yet

- AER1998 Williamson OInstitutionsof GovernanceDocument6 pagesAER1998 Williamson OInstitutionsof GovernanceJanypher MarcelaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Reforms in Developing Countries: Journal of Business Ethics May 2002Document45 pagesCorporate Governance Reforms in Developing Countries: Journal of Business Ethics May 2002Adnan HussainNo ratings yet

- David JDocument28 pagesDavid JHawiNo ratings yet

- Guth and Ginsberg 1990Document12 pagesGuth and Ginsberg 1990Fazrul Azry100% (1)

- Organizational Structure During The Twentieth CenturyDocument10 pagesOrganizational Structure During The Twentieth CenturyNoman KhosaNo ratings yet

- Evolution Based On Managerial PracticesDocument5 pagesEvolution Based On Managerial PracticesRaviraj Singh ChandrawatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2. The Evolution of Management ThinkingDocument5 pagesChapter 2. The Evolution of Management ThinkingBùi Thị Minh YếnNo ratings yet

- 2 Turnaround Management - State of The Art: 2.1 AbstractDocument11 pages2 Turnaround Management - State of The Art: 2.1 AbstractAnonymous L7XrxpeI1zNo ratings yet

- Wiley American Finance AssociationDocument26 pagesWiley American Finance AssociationBenaoNo ratings yet

- Exercising The Governance Option': Labour's New Push To Reshape Financial CapitalismDocument26 pagesExercising The Governance Option': Labour's New Push To Reshape Financial CapitalismeconstudentNo ratings yet

- Write A Short The Historical Background of Strategic ManagementDocument17 pagesWrite A Short The Historical Background of Strategic ManagementSamuel DebebeNo ratings yet

- ManagementDocument10 pagesManagementJun MendozaNo ratings yet

- LOC - Management PraticeDocument18 pagesLOC - Management PraticeJasmin PaduaNo ratings yet

- Management's Three Eras: A Brief HistoryDocument6 pagesManagement's Three Eras: A Brief HistoryCiderNo ratings yet

- Pankaj Ghemawat - Competition and Business Strategy in Historical PerspectiveDocument39 pagesPankaj Ghemawat - Competition and Business Strategy in Historical PerspectiveIndrajit LahiriNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Strategies of Matrix Organizations: Top-Level and Mid-Level Managers' Perspectives. (Awards and Management)Document14 pagesChallenges and Strategies of Matrix Organizations: Top-Level and Mid-Level Managers' Perspectives. (Awards and Management)nainokhanNo ratings yet

- j.1540-5885.2012.00920 2.xDocument5 pagesj.1540-5885.2012.00920 2.xZuzana VojtekováNo ratings yet

- Organisational AmbidexterityDocument9 pagesOrganisational AmbidexterityElena LostaunauNo ratings yet

- MergersDocument11 pagesMergersSami YaahNo ratings yet

- F1 Technical 1Document13 pagesF1 Technical 1Kidu GideyNo ratings yet

- Project Management and Business DevelopmentDocument11 pagesProject Management and Business DevelopmentnikubejNo ratings yet

- Management Functions and PrinciplesDocument12 pagesManagement Functions and PrinciplesLakshanmayaNo ratings yet

- Cocv18i3siart5 PDFDocument11 pagesCocv18i3siart5 PDFabdallah ibraheemNo ratings yet

- Chinese Business GroupsDocument11 pagesChinese Business Groups92_883755689No ratings yet

- 57 Be 3 e 4 e 2 Ec 03Document80 pages57 Be 3 e 4 e 2 Ec 03Екатерина КалашниковаNo ratings yet

- Producto BujiasDocument60 pagesProducto Bujiasjose giovanny arroyo contrerasNo ratings yet

- Catálogo Guías Bronce Aleado Aplicación-MotorDocument3 pagesCatálogo Guías Bronce Aleado Aplicación-Motorfernando yanezNo ratings yet

- AMI 2016 Catalog Final WEBDocument36 pagesAMI 2016 Catalog Final WEBallsales1No ratings yet

- General Motors Final Marketing PlanDocument26 pagesGeneral Motors Final Marketing PlanAkiyama Mio100% (2)

- January Techlink 2013 FDocument11 pagesJanuary Techlink 2013 FcherokewagNo ratings yet

- FEL PRO CatalogoDocument1,316 pagesFEL PRO Catalogoroberto mendesNo ratings yet

- Tarif Octobre 2022 - V 04-1Document1 pageTarif Octobre 2022 - V 04-1riad.sifi94No ratings yet

- Project Report Stocks Reconciliation Ashok Shalgar IIMP FINALDocument66 pagesProject Report Stocks Reconciliation Ashok Shalgar IIMP FINALak3589No ratings yet

- Running RecallsDocument1 pageRunning RecallsWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNo ratings yet

- Check Out The Buyers Guide On FacebookDocument32 pagesCheck Out The Buyers Guide On FacebookCoolerAdsNo ratings yet

- 50 Companies That Changed The World (1309)Document5 pages50 Companies That Changed The World (1309)SnehalPoteNo ratings yet

- Filters Catalogue LS 2014Document141 pagesFilters Catalogue LS 2014Steven CHENNo ratings yet

- Dealers ComplaintDocument70 pagesDealers ComplaintGMG EditorialNo ratings yet

- Selenoides Delco PDFDocument24 pagesSelenoides Delco PDFalex bonoNo ratings yet

- Injectors TbiDocument10 pagesInjectors TbiAnthonyCorsiNo ratings yet

- Tesla, IncDocument31 pagesTesla, IncxinyunNo ratings yet

- Gamma Ignition CoilsDocument22 pagesGamma Ignition CoilsCarlos MolinaNo ratings yet

- Ford Motor Company Case StudyDocument13 pagesFord Motor Company Case Studykhopdi_number1100% (1)

- Lansing Grand River Plant OpeningDocument12 pagesLansing Grand River Plant OpeningLansingStateJournalNo ratings yet

- Taxes For Revenue Are Obsolete Ruml 1946Document76 pagesTaxes For Revenue Are Obsolete Ruml 1946Daar Fisher100% (2)

- In Re:) : Debtors.)Document18 pagesIn Re:) : Debtors.)Chapter 11 DocketsNo ratings yet

- GM 10137663 Sensor Part Sales Statistics and InformationDocument9 pagesGM 10137663 Sensor Part Sales Statistics and InformationJack MitchellNo ratings yet

- DaimlerChrysler and GM Organization Technology and Business.Document6 pagesDaimlerChrysler and GM Organization Technology and Business.arbhian rizqqoNo ratings yet

- Склад гарантированного наличия (04.11.2020 (9 22 10) )Document174 pagesСклад гарантированного наличия (04.11.2020 (9 22 10) )Vladislav TeslyaNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Valvulas TRWDocument41 pagesCatalogo Valvulas TRWCold SnowNo ratings yet

- GMDocument1 pageGMAwad SalibNo ratings yet

- Case Study OligopolyDocument14 pagesCase Study OligopolyAnshul Bansal100% (4)

- 1929-57 Chevrolet Parts Catalog: "Quality Parts & Service Since 1968"Document140 pages1929-57 Chevrolet Parts Catalog: "Quality Parts & Service Since 1968"windsurferke007No ratings yet

- OP-COM Advanced Mileage ProgrammingDocument4 pagesOP-COM Advanced Mileage Programmingsucroo0% (1)

- The Toyota Way (Second Edition): 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest ManufacturerFrom EverandThe Toyota Way (Second Edition): 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest ManufacturerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (121)

- Generative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewFrom EverandGenerative AI: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Impact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic ChangeFrom EverandImpact Networks: Create Connection, Spark Collaboration, and Catalyze Systemic ChangeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- SYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsFrom EverandSYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (48)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0From EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Amp It Up: Leading for Hypergrowth by Raising Expectations, Increasing Urgency, and Elevating IntensityFrom EverandAmp It Up: Leading for Hypergrowth by Raising Expectations, Increasing Urgency, and Elevating IntensityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (50)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't (Rockefeller Habits 2.0 Revised Edition)From EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't (Rockefeller Habits 2.0 Revised Edition)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Systems Thinking: A Guide to Strategic Planning, Problem Solving, and Creating Lasting Results for Your BusinessFrom EverandSystems Thinking: A Guide to Strategic Planning, Problem Solving, and Creating Lasting Results for Your BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (80)

- Artificial Intelligence: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewFrom EverandArtificial Intelligence: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business ReviewRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- How to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffFrom EverandHow to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (61)

- Sales Pitch: How to Craft a Story to Stand Out and WinFrom EverandSales Pitch: How to Craft a Story to Stand Out and WinRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 2nd EdFrom EverandLean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 2nd EdRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (17)

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)From EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Elevate: The Three Disciplines of Advanced Strategic ThinkingFrom EverandElevate: The Three Disciplines of Advanced Strategic ThinkingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- New Sales. Simplified.: The Essential Handbook for Prospecting and New Business DevelopmentFrom EverandNew Sales. Simplified.: The Essential Handbook for Prospecting and New Business DevelopmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Small Business For Dummies: 5th EditionFrom EverandSmall Business For Dummies: 5th EditionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Your Creative Mind: How to Disrupt Your Thinking, Abandon Your Comfort Zone, and Develop Bold New StrategiesFrom EverandYour Creative Mind: How to Disrupt Your Thinking, Abandon Your Comfort Zone, and Develop Bold New StrategiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- HBR Guide to Setting Your StrategyFrom EverandHBR Guide to Setting Your StrategyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- Tax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesFrom EverandTax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesNo ratings yet

- Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition IrrelevantFrom EverandBlue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition IrrelevantRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (387)

- How to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffFrom EverandHow to Grow Your Small Business: A 6-Step Plan to Help Your Business Take OffNo ratings yet

- The Digital Transformation Playbook: Rethink Your Business for the Digital AgeFrom EverandThe Digital Transformation Playbook: Rethink Your Business for the Digital AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (48)

- The One-Hour Strategy: Building a Company of Strategic ThinkersFrom EverandThe One-Hour Strategy: Building a Company of Strategic ThinkersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Power and Prediction: The Disruptive Economics of Artificial IntelligenceFrom EverandPower and Prediction: The Disruptive Economics of Artificial IntelligenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (38)

- AI for Marketing and Product Innovation: Powerful New Tools for Predicting Trends, Connecting with Customers, and Closing SalesFrom EverandAI for Marketing and Product Innovation: Powerful New Tools for Predicting Trends, Connecting with Customers, and Closing SalesNo ratings yet

- The 10X Rule: The Only Difference Between Success and FailureFrom EverandThe 10X Rule: The Only Difference Between Success and FailureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (289)

- Strategic Risk Management: New Tools for Competitive Advantage in an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandStrategic Risk Management: New Tools for Competitive Advantage in an Uncertain AgeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business StrategyFrom Everand7 Powers: The Foundations of Business StrategyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Harvard Business Review Project Management Handbook: How to Launch, Lead, and Sponsor Successful ProjectsFrom EverandHarvard Business Review Project Management Handbook: How to Launch, Lead, and Sponsor Successful ProjectsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)