Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Close Connection (Transcript)

Close Connection (Transcript)

Uploaded by

AshleyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Close Connection (Transcript)

Close Connection (Transcript)

Uploaded by

AshleyCopyright:

Available Formats

The “Close Connection” Test in Practice

The close connection test soon gained prominence and was applied across a wide variety of situations. In

Mohamud v WM Morrison Supermarkets Plc [2016] UKSC 11; [2016] A.C. 677; the Supreme Court provided

further guidance on how the test should be applied. In Mohamud, an employee of the defendant racially abused

the claimant while working at the defendant’s petrol station. The employee then went on to assault the claimant.

At first instance and in the Court of Appeal it was found that even under the close connection test this was not in

the course of the employee’s employment; but the Supreme Court disagreed. They explained that the close

connection test should be approached in two parts. Firstly, the court should ascertain the “field of activities” of the

employee; then they should look at whether there was a sufficient connection between these activities and the

wrongdoing. Here, the employee’s job involved dealing with customers. Therefore, there was a sufficiently close

connection between that activity and assaulting a customer.

In the same year, the Court of Appeal used the “close connection” test in relation to negligence (i.e. extending it

beyond intentional torts) in Fletcher v Chancery Supplies Ltd [2016] EWCA Civ 1112.

Most recently, WM Morrison Supermarkets Plc v Various Claimants [2020] UKSC 12 [2020] 2 W.L.R. 941 has

given the Supreme Court another opportunity to clarify the test. Here, the employee in question (it is mere

coincidence that the employee also worked for WM Morrison!) had leaked payroll data in an attempt to “frame”

another employee. The Court of Appeal had found the defendant vicariously liable on the basis that there was a

causal link between the employee’s activities (processing payroll data) and the wrongdoing (making that data

available on a public website). The Supreme Court held that this was a misinterpretation of the close connection

test. The point in Mohamud was not that the events were causally connected but that the wrongdoing was a part

of the employee’s duties – he was employed to deal with customers and he was dealing with that customer, albeit

by assaulting him. Whereas in the present case, the employee was acting for entirely personal reasons and was

not closely connected to his actual job. Ironically, the Supreme Court’s judgment seems in many ways to bring

the law back towards the Salmond test, in that in Mohamud the employee was doing an authorised act in an

unauthorised way, while in Various Claimants the employee was on a “frolic of his own”!

You might also like

- Case Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date DoctrineDocument2 pagesCase Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date DoctrineZachary Philipp LimNo ratings yet

- Benefits of TravellingDocument6 pagesBenefits of TravellingLo Amanda100% (1)

- Assignment 2 Article Review ReportDocument7 pagesAssignment 2 Article Review Reportaisya kamiliaNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability Marked byDocument5 pagesVicarious Liability Marked bymohsinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 - TranscriptDocument2 pagesChapter 13 - TranscriptfmrashedNo ratings yet

- Mwai Kathebwe - Vs - Major Mkandawire and Almeida Transport Personal Injury Case No. 262 of 2017 Vicarious LiabilityDocument6 pagesMwai Kathebwe - Vs - Major Mkandawire and Almeida Transport Personal Injury Case No. 262 of 2017 Vicarious LiabilityPrince KatheweraNo ratings yet

- Tort of Vicarious LiabilityDocument95 pagesTort of Vicarious LiabilityFayia KortuNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument6 pagesVicarious LiabilityJoey WongNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability 3Document4 pagesVicarious Liability 3Triffan LNo ratings yet

- Tort Q 6Document5 pagesTort Q 6Divya NNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability EssayDocument2 pagesVicarious Liability Essaysajjad Ali balouchNo ratings yet

- Draft Assignment 2 Part AisyDocument2 pagesDraft Assignment 2 Part Aisyaisya kamiliaNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument8 pagesVicarious Liabilitybabirye rehemaNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability (Tort Law)Document9 pagesVicarious Liability (Tort Law)cs4rsrtnksNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability: Various Claimants V Morrison SupermarketDocument2 pagesVicarious Liability: Various Claimants V Morrison SupermarketNabil HazzazNo ratings yet

- Uksc 2014 0087 JudgmentDocument20 pagesUksc 2014 0087 JudgmentwickeretteNo ratings yet

- Labour Law Case Summaries 1Document16 pagesLabour Law Case Summaries 1Nene onetwoNo ratings yet

- Tort Sakshi Solanki C140Document10 pagesTort Sakshi Solanki C140Sakshi SolankiNo ratings yet

- Tort Law - Lecture 9Document4 pagesTort Law - Lecture 9jmac_411_409786403No ratings yet

- Employment LawDocument7 pagesEmployment LawNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Right of Control Test 90S161 (1979), Dy Keh Beng v. International EtcDocument1 pageRight of Control Test 90S161 (1979), Dy Keh Beng v. International EtcMarco RenaciaNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Block C - September 10, 2020 Case DigestsDocument10 pagesLabor Law Block C - September 10, 2020 Case DigestsDennis Jay Dencio ParasNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument18 pagesVicarious LiabilityAnkit TiwariNo ratings yet

- Vicariously LiabilityDocument23 pagesVicariously LiabilityJavier LimNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument2 pagesVicarious LiabilityAdarsh AdarshNo ratings yet

- Contract of Service or Contract For Service - The Supreme Court Test - Corporate - Commercial Law - IndiaDocument4 pagesContract of Service or Contract For Service - The Supreme Court Test - Corporate - Commercial Law - IndiakaranNo ratings yet

- Respondeat Superior - Let The Master Answer' - A Doctrine That Establishes That A Party IsDocument30 pagesRespondeat Superior - Let The Master Answer' - A Doctrine That Establishes That A Party IsHITESH GANGWANINo ratings yet

- Case Digest For Labor Review 2015 PART 1Document377 pagesCase Digest For Labor Review 2015 PART 1Athena SalasNo ratings yet

- Labour LawDocument5 pagesLabour Lawkelvin kanondoNo ratings yet

- Assignment Tort 2 FinalDocument3 pagesAssignment Tort 2 FinalgaiaoNo ratings yet

- Torts AnswersDocument11 pagesTorts Answerslokesh Kumar GurjarNo ratings yet

- Ingress and Egress - YmodDocument2 pagesIngress and Egress - YmodDr.Prakher SainiNo ratings yet

- For Basic Framework of Labor LawDocument5 pagesFor Basic Framework of Labor LawjanahandreasNo ratings yet

- Others '', Where The Employment Appeal Tribunal Concluded That The ClaimantsDocument2 pagesOthers '', Where The Employment Appeal Tribunal Concluded That The ClaimantsNueNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Liability: A Project by Zeeshan AhmadDocument14 pagesVicarious Liability: A Project by Zeeshan AhmadZeeshan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Justification of Liability Without Fault Under Law of TortDocument22 pagesJustification of Liability Without Fault Under Law of TortAnshul SehgalNo ratings yet

- Mohamud V MorrisonDocument20 pagesMohamud V MorrisonBriannaNo ratings yet

- Labor Digests - FinalDocument11 pagesLabor Digests - FinalMari YatcoNo ratings yet

- Labor Case DigestsDocument18 pagesLabor Case DigestsAndrea GerongaNo ratings yet

- MAGSALIN Vs NATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WORKING MEN Case DigestDocument1 pageMAGSALIN Vs NATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WORKING MEN Case DigestKornessa ParasNo ratings yet

- 7 Maula v. Ximex Delivery Exxpress DigestedDocument3 pages7 Maula v. Ximex Delivery Exxpress DigestedJug Head100% (1)

- Lazaro Vs SSSDocument2 pagesLazaro Vs SSSAshley CandiceNo ratings yet

- Labor-Law-Case-Digest-B1 ConsolidatedDocument58 pagesLabor-Law-Case-Digest-B1 ConsolidatedAgripa, Kenneth Mar R.No ratings yet

- Shining Tailors Vs Industrial Tribunal II, U. P., ... On 25 August, 1983Document2 pagesShining Tailors Vs Industrial Tribunal II, U. P., ... On 25 August, 1983vishalbalechaNo ratings yet

- Case LawsDocument1 pageCase LawsgiriNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument3 pagesCase DigestCatherine MerillenoNo ratings yet

- Labor Standards - LazadaDocument1 pageLabor Standards - LazadaHads LunaNo ratings yet

- Delict Second SemesterDocument100 pagesDelict Second SemesterfirdousNo ratings yet

- Rights of EmployerDocument5 pagesRights of EmployerMary Arlice Anne SantosNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument5 pagesVicarious Liabilitykeshni_sritharanNo ratings yet

- Magsalin Et. Al. V National Organization of Working Men Et. Al. DigestDocument2 pagesMagsalin Et. Al. V National Organization of Working Men Et. Al. DigestMark Leo BejeminoNo ratings yet

- MRL3702 01 Mark090100Document6 pagesMRL3702 01 Mark090100Edward MtekamaNo ratings yet

- 3G1718 LABREL Golangco Case DoctrinesDocument76 pages3G1718 LABREL Golangco Case DoctrinesKirstie Marie SaldoNo ratings yet

- Legal Brief Submission-Wk7Document2 pagesLegal Brief Submission-Wk7Jiahao ChenNo ratings yet

- Philippine RabbitDocument2 pagesPhilippine RabbitAnnie MendesNo ratings yet

- 3 Vicarious LiabilityDocument22 pages3 Vicarious LiabilityMuhammad AbdullahNo ratings yet

- FInal Labor Case DigestDocument27 pagesFInal Labor Case DigestIndira PrabhakerNo ratings yet

- Concept of Vicarious LiabilityDocument3 pagesConcept of Vicarious LiabilityUmesha ThilakarathneNo ratings yet

- Labor (w2-w3 Digests)Document21 pagesLabor (w2-w3 Digests)asiaNo ratings yet

- Avoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesFrom EverandAvoiding Workplace Discrimination: A Guide for Employers and EmployeesNo ratings yet

- Topic 2. Quiz 2Document4 pagesTopic 2. Quiz 2Emilio Joaquin FloresNo ratings yet

- Position Description For President of IPTN North AmericaDocument5 pagesPosition Description For President of IPTN North AmericaKiki 'Khadija' RizkiNo ratings yet

- Ncwa XiDocument46 pagesNcwa XiCheerag DamaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Problems 13.3Document7 pagesChapter 13 Problems 13.3VaneYanezNo ratings yet

- Employee Join FormDocument3 pagesEmployee Join FormSiva Shanmugam SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- 2021 HR Annual ReportDocument6 pages2021 HR Annual ReportAlex MaugoNo ratings yet

- TESDA Cicrular No. 120. S 2020 - 13 October 2020Document41 pagesTESDA Cicrular No. 120. S 2020 - 13 October 2020Shien TumalaNo ratings yet

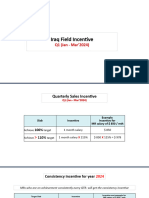

- Iraq Incentive Q1 (Jan - Mar) 2024Document6 pagesIraq Incentive Q1 (Jan - Mar) 2024حسن عباس حسن عباس الغانميNo ratings yet

- AGRA - Collated MCQs PDFDocument57 pagesAGRA - Collated MCQs PDFPaolo Antonio EscalonaNo ratings yet

- Cash Groceries/Sack of Rice Bonuses Rewards Health Incentives Others TotalDocument7 pagesCash Groceries/Sack of Rice Bonuses Rewards Health Incentives Others TotalRhyzlyn De OcampoNo ratings yet

- Anti-Discrimination PolicyDocument8 pagesAnti-Discrimination PolicyVaishali SinhaNo ratings yet

- Nail Technoligy Training AgreementDocument12 pagesNail Technoligy Training AgreementHITONo ratings yet

- Ulangan 3,4Document4 pagesUlangan 3,4warma sariNo ratings yet

- Business Review Chapter 2Document20 pagesBusiness Review Chapter 2TanishNo ratings yet

- Electronics Feasibility Study Executive Summary: Better WorkDocument8 pagesElectronics Feasibility Study Executive Summary: Better WorkFuadNo ratings yet

- IBAAEU vs. Inciong - Holiday Pay - Role of The Judiciary - Resolve Conflict in Statutory ConstructionDocument3 pagesIBAAEU vs. Inciong - Holiday Pay - Role of The Judiciary - Resolve Conflict in Statutory ConstructionJona Carmeli CalibusoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management: Strategy ImplementationDocument86 pagesStrategic Management: Strategy ImplementationBryan Joseph JumawidNo ratings yet

- Employee AbsenteeismDocument14 pagesEmployee AbsenteeismSowndarya PalanisamyNo ratings yet

- WARN Notice Benore Logist Systems-RedactedDocument5 pagesWARN Notice Benore Logist Systems-Redactedadockery_3No ratings yet

- Candidate DeclarationDocument1 pageCandidate DeclarationLenvion L0% (1)

- CNX Code of EthicsDocument47 pagesCNX Code of EthicsPrajwal ShettyNo ratings yet

- Batas Militar (1997) : A Dialectic Critique PaperDocument3 pagesBatas Militar (1997) : A Dialectic Critique PaperJana LatimosaNo ratings yet

- Resource ParkDocument92 pagesResource Parkmthara100% (2)

- Psychological Stress in Seafarers: A Review: Anna Carotenuto, Ivana Molino, Angiola Maria Fasanaro, Francesco AmentaDocument7 pagesPsychological Stress in Seafarers: A Review: Anna Carotenuto, Ivana Molino, Angiola Maria Fasanaro, Francesco AmentaHenrique DonattoNo ratings yet

- CIVIL ENGINEER CDO - May2017 Room Assignment PDFDocument21 pagesCIVIL ENGINEER CDO - May2017 Room Assignment PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities For Organizational Behavior Prime BankDocument2 pagesChallenges and Opportunities For Organizational Behavior Prime BankM. A. RakibNo ratings yet

- PHP LX 8390Document48 pagesPHP LX 8390orasesNo ratings yet

- Economic EnvironmentDocument37 pagesEconomic EnvironmentAnuja KulshrestaNo ratings yet

- Journal - Sunny 4Document6 pagesJournal - Sunny 4Mehul MehtaNo ratings yet