Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yazici Et Al - 2018 - Behçet Syndrome

Uploaded by

antonioivOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yazici Et Al - 2018 - Behçet Syndrome

Uploaded by

antonioivCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEWS

Behçet syndrome: a contemporary

view

Hasan Yazici1, Emire Seyahi2, Gulen Hatemi2 and Yusuf Yazici3

Abstract | The presence of symptom clusters, regional differences in disease expression and

similarities with, for example, Crohn’s disease suggest multiple pathological pathways are

involved in Behçet syndrome. These features also make formulating disease criteria difficult.

Genetic studies have identified HLA‑B*51 to be the important genetic risk factor. However, the

low prevalence of HLA‑B*51 in many patients with bone fide disease, especially in non-endemic

regions, suggests other factors must also be operative in Behçet syndrome. This consideration is

also true for the newly proposed ‘MHC‑I‑opathy’ concept. Despite lacking a clear aetiological

mechanism and definition, management of manifestations that include major vascular disease

(such as Budd–Chiari syndrome and pulmonary artery involvement), eye disease and central

nervous system involvement has improved with the help of new technology. Furthermore, even

with our incomplete understanding of disease mechanisms, the prognoses of patients with

Behçet syndrome, including those with eye disease, continue to improve.

Although Behçet syndrome is increasingly being recog- have occurred owing to simple oversight or because

nized, investigated and effectively managed, its aetiology distinguishing Behçet syndrome from Crohn’s disease

remains unclear. Indeed, the difficulty in developing uni- is difficult. Secondly, the ISBD criteria did not consider

versal classification criteria stems from the geographical symptom prevalence or syndrome prevalence, which

variation in prevalence and disease expression in addi- is important given the settings in which these criteria

tion to the accumulating evidence that Behçet syndrome were going to be used. To address these issues, a new set

has several clinical subsets. Paradoxically, the more we of criteria for classification and/or diagnosis of Behçet

learn, the more difficult our task of understanding syndrome has been developed3, but, like the ISBD cri-

Behçet syndrome becomes. Perhaps for this very rea- teria, does not take into consideration the baseline

son, we prefer, contrary to the prevailing view, to refer probability of any one person having Behçet syndrome

to Behçet’s as a syndrome rather than a disease. Here, we in the geographical region where these criteria will be

1

Academic Hospital, Internal discuss the emerging, most-recent evidence on the aetiol- used. This fact is important because Behçet syndrome

Medicine (Rheumatology), ogy, manifestations and epidemiology of this syndrome. shows marked geographical differences in prevalence

Nuhkuyusu cad. Uskudar, We also include updated information on prognosis and (see below, Epidemiology). Importantly, referring to

Istanbul, 34668, Turkey. management for practicing rheumatologists. disease criteria as classification criteria rather than

2

University of Istanbul,

Cerrahpaşa Medical Faculty,

diagnostic criteria does not solve the issue of pre-test

Department of Internal Disease definition and differential diagnosis probabilities. We argue that separate classification and

Medicine, Division of As virtually no unique histological or laboratory fea- diagnostic criteria are unrealistic because a diagnosis

Rheumatology, 181 tures have been identified to help in diagnosis, clinical is nothing more than the application of classification

Kocamustafapaşa, Fatih,

features are instead used to define and diagnose Behçet criteria in an individual patient4.

34098 Istanbul, Turkey.

3

New York University School syndrome (TABLE 1). Although the International Study Behçet syndrome, like all other syndromes, is a con-

of Medicine, NYU Hospital for Group Criteria for Behçet Disease (ISBD) criteria1 are struct and we propose this construct has both strong

Joint Diseases, Department the most widely used criteria, two important limitations and weak elements (TABLE 2). We define a strong element

of Medicine (Rheumatology), should be noted. Firstly, of the patients with Behçet syn- as a feature that attempts to define Behçet syndrome as

333 East 38th Street, New

York, NY, 10016, USA.

drome who were used to formulate the criteria, close a distinct nosological entity — that is, a pathological

to 80% of patients were from the Middle East (where condition with a unique pathogenesis and more or less

Correspondence to H.Y.

hasan@yazici.net associated gastrointestinal involvement is infrequent2). unique features that distinguish it from other pathological

Furthermore, the control group mainly comprised conditions. By contrast, the weak elements are those fea-

doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2017.208

Published online 3 Jan 2018 patients with various connective tissue diseases and tures that point to more than one common pathogenetic

Corrected online 24 Jan 2018 not with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis; this might mechanism5. In addition, contrary to the strong elements,

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 107

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Key points Weak elements

Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet syndrome is

• Both the disease presentation and evidence from basic studies suggest more than one one of the four weak elements of the construct (TABLE 2).

pathogenetic mechanism is involved in Behçet syndrome. Recognized vascular Distinguishing Behçet syndrome from other inflamma-

manifestations in Behçet syndrome include venous claudication, bronchial arterial tory bowel diseases can be extremely difficult19 unless

collaterals (causing haemoptysis) and ‘silent’ Budd–Chiari syndrome

other pathologies are present. For example, a study of

• The diagnostic specificity of certain manifestations, such as eye disease or vascular pathergy in our centre revealed ~10% of patients with

involvement, might be more pathognomonic than other manifestations, such as

inflammatory bowel disease who also had features of

gastrointestinal ulcerations

Behçet syndrome tested positive to the pathergy skin

• In considering the clinical and the basic science findings in Behçet syndrome, the

test, showing how difficult it can be to differentiate

weight of evidence suggests Behçet syndrome should not to be grouped with other,

seemingly related, conditions

Behçet syndrome from inflammatory bowel diseases

in general 20. Additionally, an Immunochip gene-

association study among Turkish, Japanese and Iranian

the value of weak elements in differential diagnosis might patients with Behçet syndrome identified significant

differ. Although the presence of subgroups are among the risk loci in common with Crohn’s disease21, supporting

weak elements we list in TABLE 2, they can be useful in diag- a common disease mechanism. Accordingly we pro-

nosis. For example, the sudden onset of severe headache pose gastrointestinal manifestations are weak elements

in a patient with inferior vena caval thrombosis in Behçet in the diagnosis.

syndrome should immediately alert us to the possibility of Another weak element of the construct of Behçet syn-

the presence of a dural sinus thrombosis6. drome is the marked geographic variation in its prevalence

and severity. Usually, less-severe disease expression is

Strong elements observed in non-endemic areas (see below, Epidemiology

Behçet syndrome is rarely present in the absence of a his- section). Although this variation could be the result of

tory of recurrent oral ulceration1. As such, it is an essen- differing environmental and/or genetic factors affecting

tial element of the construct because its absence strongly disease expression, the possibility of different disease

suggests another diagnosis. Three other strong elements mechanisms causing similar phenotypes cannot be ruled

have become apparent during the formal data analyses out given what we understand about Behçet syndrome.

for the ISBD criteria1 in which the presence of genital We had previously divided Behçet syndrome into

ulcers, pathergy (whereby a skin prick a develops into disease clusters or subtypes5 based on the tendency of

a papule or a pustule) and eye involvement have shown certain features to cluster together. Two such clusters

highest numerical discriminatory value to be included in are acne–arthritis–enthesitis and vascular disease sub-

the criteria set. Furthermore, a subsequent factor analy- sets. The acne–arthritis–enthesitis subset22 could have

sis7 revealed that eye disease by itself without other vari- been the main reason for the initial inclusion of Behçet

ables was disease-defining for Behçet syndrome among syndrome among the seronegative spondyloarthriti-

13 other variables examined. Indeed, eye disease as a des23 by the virtue of some shared clinical features. More

strong element was also recently supported by a study recently, interest in this subset has reemerged24 (see below,

from Tugal-Tutkun et al.8 in which ophthalmologists MHC‑I‑opathy section). The vascular disease subset has

examining retinal photographs from patients and suita- received increased attention perhaps owing to a wider

ble diseased controls could identify ocular signs of Behçet use of imaging to assess patients. Although vascular

syndrome that could be considered diagnostic even in manifestations tend to cluster together during the disease

the absence of other clinical information. Recurrent course13, which suggests more than one common patho-

genital ulcerations had the highest discriminatory value genetic mechanism, these can be helpful in diagnosing

in the ISBD criteria. Morphologically, they are similar to Behçet syndrome. For example, the onset of haemoptysis

oral ulcers, but are deeper, larger and can take longer to in a patient with suspected Behçet syndrome alerts to the

heal. Genital scarring is usually strong evidence of the presence of a pulmonary artery aneurysm rather than

presence of Behçet syndrome. Interestingly, these lesions pulmonary emboli, which are not common in Behçet

specifically locate on the scrotum in men and in the labia syndrome probably owing to the adherent nature of the

in women9, but are more-severe in men10. Finally, recent venous thrombi seen in this condition12.

evidence suggests that testosterone increases neutrophil Finally, we consider the different response to various

activity in Behçet syndrome11. drugs as weak element in our construct. The effectiveness

We also consider major vascular disease12–14 and or ineffectiveness of a certain agent to control various

parenchymal neurological involvement as strong ele- manifestations of a disease can give us clues about the

ments. These manifestations are relatively rare compared underlying disease mechanisms25. For example, colchi-

with skin and mucosal lesions and eye disease, but owing cine is useful for arthritis and erythema nodosum but not

to their unique features have substantial value in differ- particularly effective for skin-mucosa ulcers26 whereas

ential diagnosis. For example, pulmonary or peripheral thalidomide is good for oral ulcers but can exacerbate

arterial aneurysms in a young man (<45 years of age) in the erythema nodosum27. In addition, etanercept is

an endemic area is very suggestive of Behçet syndrome15. excellent for treating oral ulcers but has no effect on the

In addition, extensive lesions involving the brainstem, pathergy reaction28. We consider these varying responses

basal ganglia or isolated brainstem atrophy are quite as another indicator of our proposal that more than one

unique to and diagnostic of Behçet syndrome16–18. disease mechanism is operative in Behçet syndrome.

108 | FEBRUARY 2018 | VOLUME 14 www.nature.com/nrrheum

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

As is perhaps true in any other disease of unknown were generally considered to only be related to tissue

aetiology, more information is needed before we are able injury and not directly to the disease pathogenesis29.

to develop precise classification or diagnostic criteria. In Some clinically important differences between Behçet

the meantime, we propose that the weak elements of the syndrome and other autoimmune diseases have also been

construct of Behçet syndrome tell us we should continue noted, including sex differences in disease expression and

to evaluate emerging aetiological clues carefully. a lack of comorbidities with other autoimmune diseases30.

Interestingly, antibodies to human and mouse neurofibrils

Aetiology and pathogenesis that crossreact with Streptococcus spp. and M. tuberculosis

As for many other inflammatory rheumatological diseases heat shock proteins have recently been shown in Behçet

of unknown aetiology, Behçet syndrome had been consid- syndrome31, bringing revived consideration of an adap-

ered an autoimmune disease for many years. Supportive tive immune response in the pathogenesis — as one

of this notion were data showing T cell responses to heat would expect in an autoimmune disease.

shock proteins of Streptoccus spp. and Mycobacterium Behçet syndrome has also been considered an auto-

tuberculosis as well as autoantibodies against endothelial inflammatory disease32. It is reasonable to consider

cells, enolase and retinal S‑antigen. However, these events Behçet syndrome as a polygenic autoinflammatory

Table 1 | Features helpful in the differential diagnosis of Behçet syndrome

Feature Frequently confused with In Behçet syndrome

Oral ulcers Recurrent apthous stomatitis • More-painful, more-frequent and multiple ulcers

• Occasional major ulcerations (>1 cm in diameter), sometimes with involvement of

the soft palate and oropharynx

Papulopustular lesions Acne vulgaris • Present on upper torso and on the extremities

• Persistent at older age (>40 years of age)

Genital ulcers Reactive arthritis and Herpes • Scar-forming

simplex virus infection or other • More-frequent on the scrotum and labia

sexually transmitted infections • Rarely occur on the penis shaft, glans penis, cervix or vagina

Erythematous nodular Erythema nodosum due to a • Multiple, painful and recurrent lesions

lesions variety of causes • Occur in atypical areas (for example, face, buttocks, neck and forearms)

• Leave residual pigmentation

• Show evidence of vasculitis on histology

Non-granulomatous Other causes of infectious and • Patients are more likely to be male and young (20–30 years of age)

uveitis non-infectious uveitis • Bilateral and recurrent episodes that mainly involve the posterior pole with isolated

anterior segment involvement in ~10% of patients85

• Characterized by smooth-layered hypopyon, superficial retinal infiltrate with

retinal haemorrhages and branch retinal vein occlusion with vitreous haze

Lower extremity vein Idiopathic thrombosis, venous • Patients are more likely to be male and young (20–30 years of age)

thrombosis insufficiency and thrombophilia • Bilateral involvement with more-frequent relapses with incomplete recanalization

and more collateral formation

• Both superficial and deep veins are involved

• Post-thrombotic syndrome and venous claudication are frequent

Budd–Chiari syndrome Idiopathic, associated with • Patients are more likely to be male and young (20–30 years of age)

pregnancy or post-partum • Frequent occlusion of the inferior vena cava rather than isolated occlusion of the

and associated with hepatic veins

myeloproliferation • ‘Silent’ presentation without ascites

• Vascular interventions are unsuccessful

Cerebral venous sinus Idiopathic, Crohn’s disease and • Patients are mostly male and young (20–30 years of age)

thrombosis associated with pregnancy or • Subacute clinical onset is common

delivery • Manifests less often with focal deficits and seizures

• Venous infarcts are rare

Parenchymal CNS Multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, • Brainstem and/or basal ganglia are predominantly involved

involvement lymphoma and tuberculosis • Lesions are large and confluent, extending from the brainstem to the diencephalon

and basal ganglia

• Brainstem atrophy is almost pathognomonic

Pulmonary artery Takayasu arteritis or giant cell • Patients are more likely to be male and young (<50 years of age) especially when

involvement (PAI), arteritis associated with PAI

peripheral arterial • Uniformly thrombosed

or abdominal aortic • Mostly multiple (PAI)

aneurysms* • Usually solitary (for peripheral or abdominal aneurysms)

• Associated with fever and increased acute phase response

• Occlusions are usually thrombotic

• Stenosis or occlusions owing to homogeneous concentric wall thickness are not

compatible with Behçet syndrome

• Pulmonary arterial aneurysms are almost pathognomonic for Behçet syndrome

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 109

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Table 2 | Strong and weak elements* to discriminate Behçet syndrome

Elements Explanation

Strong

Oral ulcers Absence strongly suggests another diagnosis

Eye disease • A top discriminatory finding in a formal analysis in formulating disease criteria1

• A disease-defining factor in a factor analysis 7

• Unique findings found by ophthalmologists masked to disease at other sites 8

Genital ulceration A top discriminatory finding in a formal analysis in formulating disease criteria1

Major vascular Pulmonary arterial aneurysms are almost unique to Behçet syndrome15

involvement

Parenchymal As shown in a comparative and masked study, isolated brainstem atrophy and lesions

neurological disease extending from the brainstem to basal ganglia are quite suggestive of Behçet syndrome16

Weak

Geographical variation • Gastrointestinal disease is more frequent in far-east Asia, especially in Japan, but rather

in disease expression infrequent in Turkey.

• By contrast, vascular disease is less common in far-east Asia than in Turkey and other

Middle Eastern countries

• Milder disease has been reported among patients from non-endemic areas, such as the

United States123

Association with Crohn’s Difficult to distinguish from Crohn’s disease if extraintestinal manifestations are not

disease present19

Distinct disease subsets • Vascular disease and acne–arthritis–enthesitis clusters are two important subsets5

• Presence of these subsets suggests that more than one common pathogenetic mechanism

is operative

Different response to Varying responses to immunosuppressive treatments could be another indicator of more

various drugs than one disease mechanism in Behçet syndrome

*A strong element is defined as a feature that attempts to define Behçet syndrome as a distinct nosologic entity with a unique

pathogenesis and more or less unique disease features. A weak element points to more than one common pathogenetic

mechanism.

disease when Crohn’s disease is considered as such. For searching for what is unique about Behçet’s, will be more

example, pro-inflammatory IL‑1β is increased in active fruitful than ‘lumping’ in which likeness with other con-

Behçet syndrome, including in the aqueous humour33. ditions is sought. We will briefly elaborate on ‘lumping’

Additionally, variants of MEFV (encoding pyrin, muta- in discussing attempts to consider Behçet syndrome as

tions in which play a central part in inflammation in a MHC‑I‑opathy.

familial Mediterranean fever) as well as mutations in

genes encoding the Toll-like receptors, which are impor- MHC‑I‑opathy?

tant in innate immunity34, are also present in a minority The concept of seronegative spondyloarthritides (SpA)

of patients with Behçet syndrome. However, the pro- was introduced in 1974 to describe rheumatoid factor

posed clinical similarities between Behçet syndrome and negative inflammatory arthritis, which predominantly

monogenic autoinflammatory diseases such as familial involves the axial skeleton and sacroiliac disease. Patients

Mediterranean fever are not quite convincing35. Indeed, with this group of diseases are also frequent carriers of

two paramount differences are that almost all autoin- HLA‑B*27. Initially, Behçet syndrome had been included

flammatory diseases begin in childhood whereas Behçet in this group23; however, it was soon realized that patients

syndrome frequently begins after puberty and that with Behçet syndrome were carriers of HLA‑B*51 rather

prominent vasculitis is not a common feature of autoin- than HLA‑B*27 and that axial skeletal arthritis was not

flammatory conditions whereas at least in a major subset prominent in these patients, leading to the removal of

of those with Behçet syndrome patients display vascular Behçet’s from the SpA concept37. Recently, the debate on

involvement. Furthermore, IL‑1β blockade, which has whether this classification was correct has been rekin-

been quite successful in treating autoinflammatory dis- dled, owing to two observations24. Firstly, important data

eases, has not been convincingly successful in Behçet have emerged that some of the inflammatory pathways

syndrome36. considered operative in the seronegative SpA ankylosing

Here, we propose that because a common and dom- spondylitis (AS) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), such as

inant pathological factor for Behçet syndrome has not the IL‑10 and IL‑23–IL‑17 pathways, have also been

been identified, and that it is possible that there is no observed in Behçet syndrome24,38. Secondly, as men-

single common denominator, referring to Behçet’s as tioned, acne and arthritis commonly occur in patients

a syndrome rather than a disease is preferable. That is, with Behçet syndrome and these patients also commonly

the current evidence for disease definition and disease have enthesitis22, which is a phenotypic feature related to

mechanisms in Behçet’s suggests ‘splitting’, in which the SpA.

110 | FEBRUARY 2018 | VOLUME 14 www.nature.com/nrrheum

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Evidence in support of Behçet syndrome being In Behçet syndrome, the Janus kinase (JAK) and signal

related to AS and PsA also stems from the most impor- transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) path-

tant genetic risk factor for Behçet syndrome, HLA‑B*51 way is important45; Tulunay and colleagues investigated

(REF. 24), which is an MHC class I allele. The gene was this canonical pathway in peripheral blood mononuclear

found to be epistatic with ERAP1, which encodes endo cells from those with Behçet syndrome using whole-

plasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 — a molecule in genome microarray profiling46. They observed increased

the endoplasmic reticulum that prepares (trims) pep- JAK–STAT signalling in both CD 4+ T cells and CD4+

tides for presentation to effector cells by MHC class I monocytes compared with the healthy controls. The

molecules38–40. Importantly, polymorphisms in ERAP1 authors speculated this signalling stems from activity

have also been reported as important as susceptibility of TH1 and TH17‑type cytokines, such as IL‑2, IFNγ,

loci for PsA and AS41,42. Mechanistically, altered trim- IL‑6, IL‑17 and IL‑23, and not through TH2 cell activa-

ming of either exogenous (such as microbial) or endo tion as one would expect in an MHC class II‑associated

genous peptides by the ERAP1 variants might render autoimmune disease.

them disease-promoting or disease-preventing.

Given that Behçet syndrome, AS and PsA are asso- A microbial trigger?

ciated with variants in HLA genes encoding MHC As in other inflammatory conditions of unknown aetiol-

class I, it is interesting to note that variants in these ogy, interest in finding a microbial cause for Behçet syn-

genes are also either disease-promoting (in AS) or drome has been pursued47. However, thus far no single

disease-preventing (in Behçet syndrome 24). This pathogen has emerged as a likely candidate. Oral infec-

observation has led to the concept of ‘MHC‑I‑opathy’ tions, which had originally been proposed by Behçet

(REF. 24), and is supported by the following observa- himself to be a trigger48, have continued to be proposed

tions. Firstly, the different HLA allele associations as disease-inciting49. A collaborative study, the first for-

determine disease tissue-localized manifestations; for mal microbiome study in Behçet syndrome50, proposed

example, HLA‑B*51 is associated with eye or skin dis- a distinct salivary signature. This study revealed less bac-

ease in Behçet syndrome, HLA‑C*0602 is associated terial diversity in individuals with Behçet syndrome than

with skin lesions and increased disease severity in PsA among healthy controls; in a subset of patients, perio

and HLA‑B*27 is associated with enthesitis and eye dontal treatment corrected the oral health issues but

involvement in AS. Secondly, localized areas of stress, not the bacterial distribution. Whether these findings in

such as the entheses in AS and Behçet syndrome, or the the oral flora are causative of Behçet syndrome or a

skin, such as in the pathergy phenomenon in Behçet consequence of the condition is unclear51.

syndrome and the Koebner phenomenon in psoriasis The intestinal microbiota are also beginning to be

are important in triggering innate immunity. Thirdly, studied in Behçet syndrome and a proposal for a spe-

the immune and inflammatory responses in these dis- cific microbiome signature — namely, a paucity of

eases all share elements of both innate and adaptive genera Roseburia and Subdoligranulum along with a

pathways. decrease in butyrate production — has been made and,

In the MHC‑I‑opathy concept, more weight is more recently, an abundance of bifidobacteria has been

given to the innate immune response than to the adap- described52,53. In line with these findings, mutations in

tive immune response, suggesting that the adaptive FUT2, which encodes the fucosyltransferase 2 present

response facilitates the induction of inflammation in intestinal and oral epithelial cells, has been reported in

rather the inflammation driving the disease24. This Behçet syndrome54 — similar to what has been reported

emphasis is similar to that which has been placed on in patients with Crohn’s disease55. Epithelial α1,2‑fucose

the innate immune response as central in the pathogen- molecules formed by the enzymatic action of fucosyl-

esis of AS and PsA43. The adaptive immune response transferase 2 are important to bacterial symbiosis in the

aspect of the MHC‑I‑opathy concept is mediated by gut and also form a barrier against pathogenic bacteria56;

cytotoxic T cells, in which putative antigens presented mutations in FUT2 impair this barrier.

by the MHC class I molecules activate T helper 1 (TH1)

and TH17 cell pro-inflammatory activity24. However, Epigenetics

other cell interactions might be culpable in the patho- Epigenetic information is becoming increasingly avail-

genesis of Behçet syndrome. For example, although able in Behçet syndrome. For example, differential

altered antigen presentation by the MHC encoded by methylation of genes associated with cytoskeletal remod-

HLA‑B*51 in patients not carrying protective ERAP1 elling and cell adhesion in circulating CD4+ T cells and

polymorphisms is indeed important in causing tissue monocytes have been identified in patients with Behçet

injury, the mechanism might not rely on cytotoxic syndrome57. Importantly, these changes revert to normal

T cells44. Instead, antigen presentation might occur after treatment, particularly for genes involved in micro-

mainly to natural killer cells44. Additionally, the pres- tubule structure (KIFA2 and TPPP)58, suggesting that,

ence of HLA‑B*51 does not readily explain the cytokine with further validation, methylation patterns might be

polarization profile observed in the condition44. useful as biomarkers or theurapeutic targets.

Not restricted to a discussion of the MHC‑I‑opathy Micro RNAs, another main form of epigenetic

concept, which does not seemingly assign a specific role influence have also been studied. TH17 cell effects have

to HLA‑B*51 in cytokine polarization44, a consideration attracted particular attention in the light of miR‑155

of the mechanisms of cytokine control is also needed. expression; however, the work is still in its nascent state

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 111

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

and the results are somewhat conflicting58. In brief, Epidemiology

epigenetic influences are particularly important and Further underlying the complexity of classification and

deserve more attention in Behçet syndrome in that they definition of Behçet syndrome are regional differences

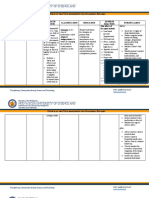

might be instrumental in explaining the geographical in disease expression. Behçet syndrome is sometimes

and envorinmental differences that are prominent in referred to as the Silk Route disease because of its fre-

this condition59. quency in the Middle East and far-east Asia (FIG. 1); these

regions have traditionally been considered the endemic

Summary areas for the condition62. However, increasing aware-

As we try to outline above, there is more to know ness of the condition along with the recent increases

about the disease mechanisms in Behçet syndrome. in human migration is changing this view. For exam-

Importantly, we currently have much better insight about ple, Behçet syndrome was traditionally viewed as very

how HLA‑B*51, the most established risk factor for rare among black individuals, but a study from Dakar,

Behçet syndrome, might be operative in pathogenesis. Senegal, reported a case series of 50 patients with Behçet

On the other hand, the frequency of HLA‑B*51 is ~60% syndrome with a proposed yearly incidence of 3.84 per

even in areas where Behçet syndrome is endemic60 and 100,000 population63. Another study showed that 70%

is much lower in other regions. This frequency certainly of patients in southern Sweden were of non-Swedish

implies the HLA B*51 association cannot wholly explain ancestry64; studying immigrant populations in tradition-

what we call Behçet’s today. Furthermore, none of the ally non-endemic areas can provide useful insights into

data discussed adequately address important manifes- gene–environment interactions and enable us to identify

tations of Behçet syndrome, such as thrombosis (with environmental and perhaps modifiable risk factors.

its resistant thrombi61) or the unique parenchymal brain For example, both Germany and the Netherlands

disease. Taken together, we consider the current evi- have sizeable Middle-Eastern immigrant populations65,66.

dence supporting the notion that Behçet’s is a syndrome In both countries, the prevalence of Behçet syndrome

rather than a disease. among immigrants is lower than that reported in

their countries of origin, but higher than that among

France Germany

• Overall 7.1 • German descent 1.5

• European descent 2.4 • Non-German European

• North African descent 34.6 descent 26.6

• Asian descent 17.5 • Turkish descent 77.4

• Sub-Saharan African descent 5.1

• Non-continental French 6.2 Iran China

80.0 14.0

Turkey

370.0

United

Kingdom

0.64

Spain 6.4

Portugal 1.5 Japan

11.9

Iraq

United States 17.0

5.2 Saudi Arabia

20.0

Italy

• Northern Italy 3.8 Israel

• Southern Italy 15.9 • Overall 15.2

• Druze descent 146.4

Egypt • Arabic descent 26.2

7.6 • Jewish descent 8.6

Nature Reviews | Rheumatology

Figure 1 | The prevalence of Behçet syndrome. Prevalence (shown as people per 100,000 population) of Behçet

syndrome is higher along the ancient Silk Route (for example, Turkey, Iran, Japan and Korea) than in other parts of the

world123. Prevalence also increases from north to south, with much lower figures in the United Kingdom than in Italy and

Spain. Immigration patterns also seem to have an increasing influence on Behçet syndrome prevalence in Europe and

have provided interesting insights. For example, studies from Germany and the Netherlands have shown that although

prevalence is higher in immigrant populations than the general German or Dutch populations, this prevalence is

somewhat lower than that in the countries of origin65,66.

112 | FEBRUARY 2018 | VOLUME 14 www.nature.com/nrrheum

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

native Germans and Dutch 65,66. The Dutch study among young males (that is, the 14–24 years of age

from Rotterdam reported that a minority of patients from and 25–34 years of age groups) whereas older males

immigrant backgrounds (14 out of 72 patients, 19%) (35–50 years of age) and females had a normal lifespan.

were indeed born in the Netherlands66. Accordingly, it Furthermore, the mortality rate was highest early after

would be of interest to know the prevalence among those disease onset (the first 7 years) and had a tendency to

who had recently migrated to the Netherlands compared decrease with time. Major causes of mortality were

with second-generation or third-generation immigrants large vessel disease and parenchymal central nervous

to better understand the role of environment factors in system (CNS) disease. Later, a French group showed

pathogenesis. a mortality rate of 5% during a median follow‑up of

In contrast with the German and Dutch studies, data 8 years in a cohort of 817 patients72. Factors associ-

from immigrants living in Paris, France, have indicated ated with mortality in this study were similar to what

that the frequency of Behçet syndrome is not different we observed10.

than that in the countries of origin67, which would pro- Quality of life is impaired in Behçet syndrome, with

vide another avenue for understanding the influence fatigue being an important problem that is correlated

of environmental factors on prevalence. However, the with quality of life, disease activity, depression, anxiety

study was a survey-based report in socially under- and physical functioning73–76. Suicidal ideation is more

privileged areas of Paris, which raises the possibility of frequent among patients with major organ involvement;

socioeconomic factors influencing the results. pain, impaired quality of life, depression, CNS involve-

In the United States, an estimated prevalence of 5.2 ment and past prednisolone use have been shown to be

per 100,000 population was reported between 1996 and independent predictors of suicidal ideation77.

2005 (REF. 68). Contemporary US data has been collected

in New York, New York, since 2005 (REF. 69). Among 313 Oral ulceration

consecutive patients, those with a northern European Oral ulcerations are usually the first as well as the most

background had more gastrointestinal disease (81 out of frequent symptoms. Minor aphthous ulcers (<10 mm in

172 patients, 47%) compared with the group of patients diameter) are the most common type. Although quite

who were ethnically from endemic areas (40 out of 141 similar to recurrent aphthous stomatitis, oral ulcers in

patients, 28%); this difference was statistically signifi- Behçet syndrome could be multiple, more painful and

cant (P = 0.001)69. For the whole New York cohort, less more frequent. Local trauma, certain types of food,

eye disease and vascular involvement than other centres menstruation and cessation of smoking are described as

from Turkey and Japan was reported69. Approximately triggering factors78. The frequent occurrence of attacks

one-third of patients had eye disease in each group; of oral ulceration during early Behçet’s was found to pre-

interestingly with only one blind eye in total. Similarly, dict the development of major organ involvement among

milder disease has also been reported among patients male patients79. Oral ulcers continue to develop for many

from other non-endemic areas70. years after disease onset80, but all other manifestations

Clearly, more comparative epidemiology work is usually resolve10.

needed in Behçet syndrome to guide us in diagnosis,

for fair allocation of resources and perhaps decipher Eye involvement

the disease mechanisms in this very complex condition. Lesions — such as a smooth-layered hypopyon (a leu-

Perhaps in comparative formal hospital-based surveys, kocytic exudate in the anterior chamber of the eye),

which use the frequencies of other diseases, such as superficial retinal infiltrates with retinal haemorrhages

rheumatoid arthritis, that do not have apparent differ- and branch retinal vein occlusion with vitreous haze —

ences in frequency across different geographies, Behçet’s were identified as pathognomonic for Behçet syndrome

can be of help71. uveitis as indicated above8. Specialized imaging tech-

niques such as optical coherence tomography (OCT)

Clinical manifestations and fluorescein angiography are becoming useful tools

Clinical manifestations in Behçet syndrome are variable in the diagnosis and assessment of disease activity81–83.

and characterized by unpredictable periods of recur- Additionally, central foveal thickness has been suggested

rences and remissions, although the frequency and as a non-invasive measure to assess inflammatory activ-

severity tend to abate with time. Skin-mucosa lesions ity in early uveitis82 and localized non-glaucomatous ret-

are the most common manifestation and are usually inal nerve fibre layer defects, as an indicator of posterior

the presenting symptoms, whereas ocular, vascular and pole involvement83.

neurological involvement are less common but more The prognosis of eye disease has improved in recent

serious10,12,14,17,18. The overall mortality rate of patients years. For example, Chung et al.84 reported that mean

with Behçet syndrome is significantly increased among visual acuity was better among patients whose first

younger men (<25 years of age) and early in the disease visit to a dedicated Behçet syndrome clinic in Korea

course among those with major organ involvement. In was between 2004 and 2010, than those who registered

a 20 year follow‑up study of a large inception cohort in between 1994 and 2000. Similarly, Cingu et al.85 reported

our dedicated clinic (n = 428, of which 286 were male that the risk of losing useful vision was lower in patients in

and 142 were female), a total of 42 (39 male, 3 female) Turkey who presented between 2000 and 2004 than

patients had died at the end of the survey10. Age-matched in patients who presented between 1990 and 1994. They

standardized mortality ratios were specifically increased observed that the risk of having loss of useful vision at

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 113

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

3 years of follow‑up decreased from 27.6% (43 out of venous claudication88 (FIG. 2a). PAI can manifest as pul-

156 eyes) in the 1990s to 12.9% (26 out of 201 eyes) in monary arterial aneurysms and single in situ pulmonary

the 2000s. In line with this finding, risk of having loss of arterial thromboses12 (FIG. 2b). A wide range of pulmo-

useful vision was 13% at 10 years of follow‑up in a study nary parenchymal lesions such as nodules, consolidations

by Taylor et al.86 in the United States and 14.4% at 1‑year and cavities are also part of the vascular manifestations12.

of follow‑up in a study by Accorinti et al.87 in Italy. Mild elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure can be

associated with PAI89 and bronchial arterial collaterals

Vascular involvement emerge as another cause of haemoptysis in patients with

Except for non-pulmonary arterial disease, which occurs Behçet syndrome who are in remission90. Aneurysms

at a later age (≥40 years of age), 75% of patients with or thromboses can regress in ~70% of patients with

Behçet syndrome experience their first vascular event immunosuppressive treatment12. The relapse rate is ~20%

within 5 years of disease onset13. Additionally, the cumu- and mortality rate is ~25% at 7 years, despite tight control

lative relapse rate of vascular events was found to be 23% of disease activity, frequent medical visits and aggressive

at 2 years and 38% at 5 years13. In the vascular subset management12. Increased diameter of the aneurysms

(see above and TABLE 2), several types of vascular man- and high pulmonary arterial pressures at presentation

ifestation tend to occur in the same individual, creating are poor prognostic factors for survival12.

statistically significant associations across all patients; Budd–Chiari syndrome mostly involves the inferior

for example, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and pul- vena cava (the suprahepatic and hepatic segments) and

monary artery involvement (PAI) tend to co‑occur, as the hepatic veins. In patients who present with ascites

do intracardiac thrombosis and PAI, and Budd–Chiari (FIG. 2c), the mortality rate is ~60% within a median of

syndrome and inferior vena cava syndrome12–14. 10 months after diagnosis14. However, in some patients,

Lower extremity vein thrombosis (superficial and Budd–Chiari syndrome develops gradually without

deep) is the most common form of vascular involve- ascites. Imaging studies using ultrasonography or CT

ment and leads to severe post-thrombotic syndrome and show that these individuals have efficient collateral for-

mations. These ‘silent’ patients have more favourable

outcomes, with <10% expected mortality at 7 years14.

a c

CNS involvement

CNS disease occurs in 5–10% of patients with Behçet

syndrome, mostly in the form of parenchymal brain

involvement. Brainstem involvement is the most char-

acteristic type of involvement. Pyramidal signs, hemi-

paresis, behavioural–cognitive changes, sphincter

disturbances and/or impotence are the main clinical

manifestations of CNS involvement. Psychiatric problems

b might also develop in some patients91.

Sometimes, the clinical presentation of CNS disease

in Behçet syndrome can be taken for multiple sclero-

sis, in which case MRI findings are helpful91. In contrast

to the large extensive lesions of CNS involvement in

Behçet syndrome, multiple sclerosis has more discrete

and smaller brainstem lesions. Optic neuritis, sensory

symptoms and spinal cord involvement, which are com-

mon in multiple sclerosis, are seldom observed in Behçet

syndrome. White matter lesions are also different: in

multiple sclerosis, lesions tend to be supratentorial and

periventricular with corpus callosum involvement,

Figure 2 | Vascular involvement in Behçet syndrome. Vascular involvement is an early whereas in Behçet syndrome, lesions are small, bihemi-

Nature Reviews | Rheumatology

and relapsing event in Behçet syndrome and occurs in up to 40% of patients. spheric and subcortical. The cerebrospinal fluid patterns

a | Ulceration on the distal tibia in a 34‑year-old male patient. Superficial and deep also differ: pleocytosis is more prominent in multiple

femoral vein thromboses were the initial symptoms, which recurred despite sclerosis, whereas oligoclonal band positivity (that is,

immunosuppressive treatment. Eventually, post-thrombotic syndrome with ulceration, the gold-standard test for multiple sclerosis) is rarely

oedema, induration, hyperpigmentation and superficial skin collaterals developed. observed in Behçet syndrome91.

b | Bilateral, multiple pulmonary arterial aneurysms (arrows) on a CT scan of a 28‑year-old Compared with patients with multiple sclerosis,

male with Behçet syndrome who presented with haemoptysis, chest pain, dyspnoea and

patients with Behçet syndrome who have CNS involve-

fever. Additionally, mural thrombosis inside the aneurysms can be observed. c | Thorax of

a 26‑year-old male with juvenile-onset Behçet syndrome who presented with ascites, ment have poorer performance on several measures of

abdominal pain and fever. The hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava and all three cognitive status92. Moreover, a subgroup of patients with

hepatic veins were occluded with thrombi. Intensive immunosuppressive treatment Behçet syndrome may present with multiple sclerosis-

resolved most of the symptoms, although he subsequently developed bilateral like features on MRI93. These patients were more likely

gynaecomastia and diffuse abdominal collaterals, which can be ascribed to residual mild to be female, to have increased number of neurological

liver insufficiency. attacks, to have a higher rate of oligoclonal band and to

114 | FEBRUARY 2018 | VOLUME 14 www.nature.com/nrrheum

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

have less pleocytosis. This implicates that disease mech- baseline) that predict a better outcome. Although sev-

anisms in multiple sclerosis and Behçet syndrome might eral outcomes and outcome measures have been used in

be similar. Finally, quantitative analysis of the brainstem clinical trials, many of these have not been validated or

by MRI has been suggested as an effective diagnostic tool widely accepted98. The variability in outcomes and out-

for, as well as in monitoring the evaluation of disease come measures has made it difficult to compare the effi-

activity in, chronic progressive Behçet syndrome with cacy of treatment modalities and help make treatment

CNS involvement94 (FIG. 3). decisions99. Furthermore, the assessment of Behçet syn-

Finally, Noel et al.95 investigated the outcomes of drome is complicated owing to the frequently relapsing

a large cohort of patients (n = 115) with CNS involve- but less-disabling skin, mucosal and joint involvement

ment, excluding dural sinus thrombosis. The authors against a backdrop of the less-frequent but more-serious

found that after a median follow‑up of 6 years, 30% of (and even life threatening) nature of major organ

patients relapsed after immunosuppressive treatment, involvement. Efforts are ongoing to develop a core set of

25% of patients became dependent on care takers and outcome measures for Behçet syndrome clinical trials100.

10% had died95. Despite these difficulties, management can still be

individualized depending on what we know regarding

Gastrointestinal involvement the prognoses of patients with Behçet syndrome. This

Gastrointestinal involvement in Behçet syndrome approach is also emphasized in the 2016 EULAR recom-

resembles Crohn’s disease in its presentation, with mendations101. Younger patients and male patients who

abdominal pain and diarrhoea that may be accompanied have higher risk of severe disease should be followed‑up

by bleeding, and is an uncommon manifestation in geog- closely for the development of major organ involvement

raphies other than in far-east Asia2. Behçet syndrome and treated aggressively when such involvement is noted.

usually causes round or oval ulcers most commonly

in the terminal ileum96. Ulcers are usually deep, large Skin, mucosal and joint involvement

and single with a tendency to perforate or cause mas- The management of patients with only skin, mucosal

sive bleeding. Mucosal biopsies show chronic or active and joint involvement is determined by the frequency

mucosal inflammation as well as vasculitic findings in a and severity of their lesions and the extent to which these

small proportion of patients96. Faecal calprotectin levels lesions impair their quality of life. The patient’s percep-

are associated with disease activity, similar to Crohn’s tion and preferences are important in making treatment

disease97. Even with treatment, relapses may occur in decisions as these lesions do not cause damage and are

~20% of patients96. neither organ-threatening nor life-threatening.

Topical treatments such as corticosteroids help to

Management and outcome measures decrease the severity and duration of lesions and can

The goals of management in Behçet syndrome are to be used without the need of continuous systemic treat-

rapidly suppress inflammatory exacerbations and ment in patients whose recurrences are infrequent and

to prevent relapses to maintain good quality of life do not cause much discomfort. Systemic treatment

and preserve organ function. A treat‑to‑target strategy modalities are used when it is necessary to prevent

has not been well established owing to a lack of stand- recurrences. Colchicine is usually the initial choice of

ardized outcome measures that define remission, low treatment owing to its safety profile and low cost (FIG. 4).

disease activity or a target score (or level of change from However, it has limited efficacy, especially for oral ulcers.

a b c

Figure 3 | CNS involvement in Behçet syndrome. Cranial MRI scans a 30‑year-old male patient with Behçet syndrome of

12 years’ duration. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement began 10 years after diagnosis withReviews

Nature severe headache,

| Rheumatology

speech difficulties, swallowing problems and cognitive disturbances. a | MRI T2‑weighted axial sequence show pontine

(arrow) and cerebellar (arrowhead) atrophy. b | Also evident are an ischaemic lesion on the pons (arrow) and fourth

ventricle dilatation (arrowhead), which are other characteristic lesions of brainstem atrophy. c | Sagittal sequence similarly

shows the same lesions (arrow).

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 115

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

Lactobacilli lozenges might be used102. Apremilast (a Behçet syndrome and to identify any patient character-

phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor) was shown to be rel- istics that would mandate the use of one of these agents

atively safe and effective for oral and genital ulcers103. or the other.

Thalidomide, IFNα and etanercept are other alternatives Anti‑IL‑1, anti‑IL‑6 and anti‑IL‑17 agents have

for refractory skin, mucosal and joint lesions27,28,104. also been tried in patients with refractory eye disease.

In terms of emerging treatments, a small open-label A pilot study and an uncontrolled phase II study, both

study of anakinra (an IL‑1 receptor antagonist) for with small numbers of patients, showed beneficial results

skin-mucosa involvement showed that only two out of six with the IL‑1 blocker gevokizumab107,108; the randomized

patients had no oral ulcers on two consecutive monthly controlled trial of this agent was terminated as it did not

visits105. The dose had to be increased (to 200 mg per achieve its primary end point36. Secukinumab (which

day from 100 mg per day) in all but one patient after inhibits IL‑17A) had also failed to meet its primary end

1 month. Additionally, an open-label prospective study point of reduction of uveitis recurrence in a randomized

of ustekinumab (which inhibits IL‑12 and IL‑23) showed controlled trial109. A systematic review of case reports

a decrease in the median number of oral ulcers from two and a small case series with tocilizumab (an IL‑6 recep-

ulcers to one ulcer after 12 weeks106. tor inhibitor) in patients refractory to IFNα and inflixi-

mab suggest that this agent may be effective in protecting

Major organ involvement visual acuity, reducing central macular thickness and

Patients with major organ involvement should be treated improving fluorescein angiography findings110,111.

effectively to prevent damage. Posterior uveitis is man- Arterial aneurysms are treated with high-dose gluco

aged with immunosuppressive agents such as azathio- corticoids and monthly cyclophosphamide pulses fol-

prine, ciclosporin, IFNα and anti-TNF antibodies (such lowed by maintenance therapy with azathioprine112

as infliximab) together with glucocorticoids. The deci- (FIG. 4). Surgery might be required for peripheral artery

sion to use IFNα or anti-TNF agents as first-line treat- aneurysms113. Anti-TNF agents can be used in patients

ment or to save these for patients with uveitis who fail who fail to respond to this regimen114. Consensus among

or relapse on azathioprine and/or ciclosporin depends experts is that immunosuppressive treatments such as

on the severity of the eye involvement, experience of the azathioprine or ciclosporin should be used for deep

physician and reimbursement policies. Furthermore, vein thromboses as in Behçet syndrome these result

head‑to‑head controlled trials are needed to demon- from inflammation of the venous wall rather than a

strate the superiority of IFNα or anti-TNF agents in pro-coagulant state115. The use of anticoagulants is

Skin and Venous Pulmonary Peripheral CNS Gastrointestinal

Joints Uveitis

mucosa thrombosis aneurysms aneurysms involvement involvement

Topical Topical and/or

Surgery oral 5-ASA

corticosteroids

+ derivatives*

• Colchicine (1.5 mg per day) • Azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg • Cyclophosphamide • Azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg per

• Lactobacilli lozenges per day) (1 g per month for day)‡

• Azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg • IFNα (5 MU per day) 6 months) followed • Infliximab (5 mg per kg)

per day) by azathioprine • Or adalimumab (40 mg every

• Infliximab (5 mg per kg) (2.5 mg/kg per day)

• IFNα (3–5 MU 3/7 days • Or adalimumab (40 mg other week)

per week) every other week) • Infliximab (5 mg per kg)

• Etanercept (50 mg per

week)

Glucocorticoids

Figure 4 | Management of Behçet syndrome. Treatment is individualized to each patient according to the type and

severity of organ involvement, patient age, patient sex and disease duration. In our centre (Cerrahpaşa Medical Faculty,

Turkey) patients with only skin-mucosa involvement and joint involvement can be managed with topical

Nature Reviewsagents and

| Rheumatology

colchicine. Those who continue to have bothersome lesions despite these measures can be prescribed

immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agents such as azathioprine, IFNα, thalidomide, apremilast or anti-TNF agents.

In patients with eye, vascular, central nervous system (CNS) or gastrointestinal involvement immunosuppressive agents

such as azathioprine are used as first-line treatments. Biological agents such as IFNα or anti-TNF antibodies are used in

patients refractory to immunosuppression. Cyclophosphamide is usually the first choice for the initial treatment of arterial

aneurysms that are life threatening. Pulmonary lobectomies in cases of giant pulmonary arterial aneurysms, or surgical

resection of peripheral large aneurysms, can also be performed after immunosuppressive treatment. Glucocorticoids can

be used for rapid suppression of inflammatory flares to prevent damage in all types of involvement. 5‑ASA,

5‑aminosalicylic acid. *Mild cases. ‡Moderate and severe cases.

116 | FEBRUARY 2018 | VOLUME 14 www.nature.com/nrrheum

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

controversial because case–control studies have not Conclusions

shown a beneficial effect in preventing relapses of deep The management of Behçet syndrome is increasingly

vein thromboses116, but controlled data are needed to ver- successful, even if the precise definition of the condi-

ify this finding and to understand whether other benefits, tion is lacking. Indeed, Behçet syndrome is a complex

such as preventing post-thrombotic syndrome, exist. construct with what we propose as strong and weak ele-

Parenchymal CNS involvement is treated with high- ments. The strong elements are those clinical findings

dose glucocorticoids together with immunosuppressive the presence or absence of which differentiate Behçet’s

therapy such as azathioprine or anti-TNF agents; ciclo- from other diseases or syndromes. The weak elements, on

sporin is avoided as it is neurotoxic117. The role of IL‑6 the other hand, are features that suggest more than one

blockers, which seem promising for CNS involvement pathogenetic mechanism might be involved in Behçet’s

based on a small case series110 (in which high IL‑6 levels and might also be useful in differential diagnosis.

were observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with The clinical picture of Behçet syndrome is further

CNS disease118,119) need to be further explored. complicated by a lack of specific histopathology or

The initial management of gastrointestinal involve- laboratory components that can be used in diagnosis.

ment is with 5‑aminosalicylic acid derivatives in As said, the precise disease mechanisms that underlie

patients with mild disease. In those with moderate or the symptoms are not fully deciphered and difficult to

severe gastrointestinal involvement, azathioprine is rec- do so owing, in part, to regional differences in disease

ommended96. Anti-TNF agents and thalidomide can expression. Despite advances in molecular genetics and

be used in patients with refractory gastrointestinal in understanding potentially implicated inflammatory

involvement120 (FIG. 4). pathways (for example, those related to HLA‑B*51) the

Finally, a systematic review of patients with Behçet current construct of what comprises Behçet syndrome

syndrome treated with haematopoietic stem cell trans- remains rather complex. More basic, translational and

plantation for either refractory major organ involvement clinical work is needed, with emphasis placed on under-

or a comorbid haematological condition showed that standing phenotypic expression and geographic influ-

this approach was successful in inducing remission of ence. Additionally, as evidence continues to emerge on

Behçet syndrome lesions in 18 of 19 patients121. However Behçet syndrome, a clearer definition should emerge

graft-versus-host disease and infections occurred in — we believe, encouraging a splitters approach and

some of the patients and one patient died owing to allowing Behçet syndrome not to be grouped with other,

infection after 2 months. somewhat related, conditions122.

1. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. 13. Tascilar, K. et al. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s 24. McGonagle, D., Aydin, S. Z., Gül, A., Mahr, A. &

Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 335, syndrome: a retrospective analysis of associations and Direskeneli, H. ‘MHC‑I‑opathy’ — unified concept for

1078–1080 (1990). the time course. Rheumatology 53, 2018–2022 spondyloarthritis and Behçet disease. Nat. Rev.

2. Skef, W. Gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: a review. (2014). Rheumatol. 11, 731–740 (2015).

World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 3801 (2015). 14. Seyahi, E. et al. An outcome survey of 43 patients with 25. Schett, G. et al. Enthesitis: from pathophysiology to

3. Davatchi, F. et al. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Budd-Chiari syndrome due to Behçet’s syndrome treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 731–741 (2017).

Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries followed up at a single, dedicated center. Semin. 26. Yurdakul, S. et al. A double-blind trial of colchicine in

on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 602–609 (2015). Behçet’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 2686–2692

J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 28, 338–347 15. Melikoglu, M., Kural-Seyahi, E., Tascilar, K. & Yazici, H. (2001).

(2013). The unique features of vasculitis in Behçet’s syndrome. 27. Hamuryudan, V. Thalidomide in the treatment of the

4. Yazici, H. & Yazici, Y. Diagnosis and/or classification Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 35, 40–46 (2008). mucocutaneous lesions of the Behcet syndrome.

of vasculitis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 28, 3–7 16. Çoban, O. et al. Masked assessment of MRI findings: Ann. Intern. Med. 128, 443 (1998).

(2016). is it possible to differentiate neuro-Behçet’s disease 28. Melikoglu, M. et al. Short-term trial of etanercept in

5. Yazici, H., Ugurlu, S. & Seyahi, E. Behçet syndrome: is from other central nervous system. Neuroradiology Behçet’s disease: a double blind, placebo controlled

it one condition? Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 43, 41, 255–260 (1999). study. J. Rheumatol. 32, 98–105 (2005).

275–280 (2012). 17. Siva, A. et al. Behçet’s disease: diagnostic and 29. Direskeneli, H. Autoimmunity versus

6. Tunc, R., Saip, S., Siva, A. & Yazici, H. Cerebral venous prognostic aspects of neurological involvement. autoinflammation in Behcet’s disease: do we

thrombosis is associated with major vessel disease in J. Neurol. 248, 95–103 (2001). oversimplify a complex disorder? Rheumatology 45,

Behçet’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 18. Akman-Demir, G., Serdaroglu, P., Tasçi, B. & The 1461–1465 (2006).

1693–1694 (2004). Neuro-Behçet Study Group. Clinical patterns of 30. Yazici, H. The place of Behçet’s syndrome among the

7. Tunc, R., Keyman, E., Melikoglu, M., Fresko, I. & neurological involvement in Behçet’s disease: autoimmune diseases. Int. Rev. Immunol. 14, 1–10

Yazici, H. Target organ associations in Turkish evaluation of 200 patients. Brain 122, 2171–2182 (1997).

patients with Behçet’s disease: a cross sectional (1999). 31. Lule, S. et al. Behçet disease serum is immunoreactive

study by exploratory factor analysis. J. Rheumatol. 19. Valenti, S., Gallizzi, R., De Vivo, D. & Romano, C. to neurofilament medium which share common

29, 2393–2396 (2002). Intestinal Behçet and Crohn’s disease: two sides of the epitopes to bacterial HSP‑65, a putative trigger.

8. Tugal-Tutkun, I., Onal, S., Ozyazgan, Y., Soylu, M. & same coin. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 15, 33 (2017). J. Autoimmun. 84, 87–96 (2017).

Akman, M. Validity and agreement of uveitis 20. Hatemi, I. et al. Frequency of pathergy phenomenon 32. Gul, A. Behçets disease as an autoinflammatory

experts in interpretation of ocular photographs for and other features of Behçet’s syndrome among disorder. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 4,

diagnosis of Behçet uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. 81–83 (2005).

Inflamm. 22, 461–468 (2013). Rheumatol. 26, S91–95. 33. Franks, W. A. et al. Cytokines in human intraocular

9. Mat, M. C., Goksugur, N., Engin, B., Yurdakul, S. & 21. Takeuchi, M. et al. Dense genotyping of immune- inflammation. Curr. Eye Res. 11, 187–191 (1992).

Yazici, H. The frequency of scarring after genital ulcers related loci implicates host responses to microbial 34. Kirino, Y. et al. Targeted resequencing implicates

in Behçet’s syndrome: a prospective study. exposure in Behçet’s disease susceptibility. the familial Mediterranean fever gene MEFV and

Int. J. Dermatol. 45, 554–556 (2006). Nat. Genet. 49, 438–443 (2017). the toll-like receptor 4 gene TLR4 in Behçet disease.

10. Kural-Seyahi, E. et al. The long-term mortality and 22. Hatemi, G., Fresko, I., Tascilar, K. & Yazici, H. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8134–8139 (2013).

morbidity of Behçet syndrome. Medicine 82, 60–76 Increased enthesopathy among Behçet’s syndrome 35. Yazici, H. & Fresko, I. Behçet’s disease and other

(2003). patients with acne and arthritis: An ultrasonography autoinflammatory conditions: what’s in a name? Clin.

11. Yavuz, S. et al. Activation of neutrophils by study. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 1539–1545 (2008). Exp. Rheumatol. 23 (Suppl. 38), S1–S2 (2005).

testosterone in Behçet’s disease. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 23. Moll, J. M. H., Haslock, I. A. N., Macrae, I. F. & 36. US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://

25 (Suppl. 45), S46–S51 (2007). Wright, V. Associations between ankylosing clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01965145 (2017).

12. Seyahi, E. et al. Pulmonary artery involvement and spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s disease, the 37. Rudwaleit, M. in Rheumatology 5th edn (eds

associated lung disease in Behçet disease. Medicine intestinal arthropathies, and Behcet’s syndrome. Hochberg, M., Silman, A., Smolen, J., Weinblatt, M.

91, 35–48 (2012). Medicine 53, 343–364 (1974). & Weisman, M.) 1123–1127 (Mosby Elsevier, 2011).

NATURE REVIEWS | RHEUMATOLOGY VOLUME 14 | FEBRUARY 2018 | 117

©

2

0

1

8

M

a

c

m

i

l

l

a

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

i

m

i

t

e

d

,

p

a

r

t

o

f

S

p

r

i

n

g

e

r

N

a

t

u

r

e

.

A

l

l

r

i

g

h

t

s

r

e

s

e

r

v

e

d

.

REVIEWS

38. Remmers, E. F. et al. Genome-wide association study 61. Becatti, M. et al. Neutrophil activation promotes 84. Chung, Y.‑R., Lee, E.‑S., Kim, M. H., Lew, H. M. &

identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and fibrinogen oxidation and thrombus formation in Song, J. H. Changes in ocular manifestations of Behçet

IL23R‑IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet’s Behçet’s disease. Circulation 133, 302–311 (2015). disease in Korean patients over time: a single-center

disease. Nat. Genet. 42, 698–702 (2010). 62. Verity, D. H., Marr, J. E., Ohno, S., Wallace, G. R. & experience in the 1990s and 2000s. Ocul. Immunol.

39. Ombrello, M. J. et al. Behcet disease-associated MHC Stanford, M. R. Behcet’s disease, the Silk Road and Inflamm. 23, 157–161 (2014).

class I residues implicate antigen binding and HLA‑B51: historical and geographical perspectives. 85. Cingu, A. K., Onal, S., Urgancioglu, M. & Tugal-

regulation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl Tissue Antigens 54, 213–220 (1999). Tutkun, I. Comparison of presenting features and

Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8867–8872 (2014). 63. Ndiaye, M. et al. Behçet’s disease in black skin. A three-year disease course in Turkish patients with

40. Kirino, Y. et al. Genome-wide association analysis retrospective study of 50 cases in Dakar. J. Dermatol. Behçet uveitis who presented in the early 1990s and

identifies new susceptibility loci for Behçet’s disease Case Rep. 9, 98–102 (2015). the early 2000s. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 20,

and epistasis between HLA‑B*51 and ERAP1. 64. Mohammad, A., Mandl, T., Sturfelt, G. & 423–428 (2012).

Nat. Genet. 45, 202–207 (2013). Segelmark, M. Incidence, prevalence and clinical 86. Taylor, S. R. J. et al. Behçet disease: visual prognosis

41. Evans, D. M. et al. Interaction between ERAP1 and characteristics of Behcet’s disease in southern and factors influencing the development of visual loss.

HLA‑B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide Sweden. Rheumatology 52, 304–310 (2012). Am. J. Ophthalmol. 152, 1059–1066 (2011).

handling in the mechanism for HLA‑B27 in disease 65. Papoutsis, N. G. et al. Prevalence of Adamantiades- 87. Accorinti, M., Pesci, F. R., Pirraglia, M. P., Abicca, I. &

susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 43, 761–767 (2011). Behçet’s disease in Germany and the municipality of Pivetti-Pezzi, P. Ocular Behçet’s disease: changing

42. Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium & the Berlin: results of a nationwide survey. Clin. Exp. patterns over time, complications and long-term visual

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. A genome- Rheumatol. 24 (Suppl 42), S125 (2006). prognosis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 25, 29–36 (2016).

wide association study identifies new psoriasis 66. Kappen, J. H. et al. Behçet’s disease, hospital-based 88. Seyahi, E. et al. Clinical and ultrasonographic

susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA‑C prevalence and manifestations in the Rotterdam area. evaluation of lower-extremity vein thrombosis in

and ERAP1. Nat. Genet. 42, 985–990 (2010). Neth. J. Med. 73, 471–477 (2015). Behcet syndrome. Medicine 94, e1899 (2015).

43. Ambarus, C., Yeremenko, N., Tak, P. P. & Baeten, D. 67. Mahr, A. et al. Population-based prevalence study of 89. Seyahi, E. et al. The estimated pulmonary artery

Pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis: autoimmune or Behçet’s disease: differences by ethnic origin and low pressure can be elevated in Behçet’s syndrome.

autoinflammatory? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 24, variation by age at immigration. Arthritis Rheum. 58, Respir. Med. 105, 1739–1747 (2011).

351–358 (2012). 3951–3959 (2008). 90. Esatoglu, S. N. et al. Bronchial artery enlargement

44. Giza, M., Koftori, D., Chen, L. & Bowness, P. Is 68. Calamia, K. T. et al. Epidemiology and clinical may be the cause of recurrent haemoptysis in Behçet’s

Behçet’s disease a ‘class 1‑opathy’? The role of characteristics of behçet’s disease in the US: a syndrome patients with pulmonary artery involvement

HLA‑B*51 in the pathogenesis of Behçet’s disease. population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 61, during follow‑up. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 34 (Suppl.

Clin. Exp. Immunol. 191, 11–18 (2017). 600–604 (2009). 102), 92–96 (2016).

45. Schwartz, D. M., Bonelli, M., Gadina, M. & 69. Yazici, Y., Filopoulos, M. T., Schimmel, E., 91. Siva, A. & Saip, S. The spectrum of nervous system

O’Shea, J. J. Type I/II cytokines, JAKs, and new McCraken, A. & Swearingen, C. Clinical involvement in Behçet’s syndrome and its differential

strategies for treating autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. characteristics, treatment and ethnic/racial differences diagnosis. J. Neurol. 256, 513–529 (2009).

Rheumatol. 12, 25–36 (2015). in the manifestations of 518 Behcet’s syndrome 92. Gündüz, T. et al. Cognitive impairment in neuro-

46. Tulunay, A. et al. Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway patients in the United States [abstract]. Arthritis. Behcet’s disease and multiple sclerosis: a comparative

in Behcet’s disease. Genes Immun. 16, 170–175 Rheum. 62 (Suppl.), 1284 (2010). study. Int. J. Neurosci. 122, 650–656 (2012).

(2014). 70. Salvarani, C. et al. Epidemiology and clinical course of 93. Akman-Demir, G. et al. Behçet’s disease patients with

47. Hatemi, G. & Yazici, H. Behçet’s syndrome and micro- Behçet’s disease in the Reggio Emilia area of Northern multiple sclerosis-like features: discriminative value of

organisms. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 25, Italy: a seventeen-year population-based study. Barkhof criteria. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 33 (Suppl. 94),

389–406 (2011). Arthritis Rheum. 57, 171–178 (2007). S80–S84 (2015).

48. Behçet, H. Über residivierende aphtose, durch ein 71. Madanat, W. Y. et al. The prevalence of Behçet disease 94. Kikuchi, H., Takayama, M. & Hirohata, S. Quantitative

virus verursachte geschwüre am mund, am auge und in the north of Jordan: a hospital based analysis of brainstem atrophy on magnetic resonance

den genitalen [German]. Dermatol. Wochenschrift. epidemiological survey. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol 35 imaging in chronic progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease.