Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HRCSL Letter To President On CTUR

HRCSL Letter To President On CTUR

Uploaded by

Adaderana Online0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

297 views4 pagesHRCSL Letter to President on CTUR

Original Title

HRCSL Letter to President on CTUR

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHRCSL Letter to President on CTUR

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

297 views4 pagesHRCSL Letter To President On CTUR

HRCSL Letter To President On CTUR

Uploaded by

Adaderana OnlineHRCSL Letter to President on CTUR

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

ead aun eens

siomgy Geo. pas

My No Date

08) quae

aeiae | 17 January 2024

Your No

& Eom Had 68n5 combos amd

Baris wats 2 feowact Henemd Huy

Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka

HLE. Ranil Wickremesinghe

President of the Republic of Sri Lanka,

Presidential Secretariat,

Colombo 01

Your Excellency,

Observations and Recommendations on the Commission for Truth, Unity and

Reconciliation in Sri Lanka Bill

We write to you with reference to the Bill titled ‘Commission for Truth, Unity and Reconciliation

in Sri Lanka’ (CTUR) shared with the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka by the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs on 18 December 2023 and published in the Official Gazette of 29 December 2023

‘We write to you in terms of the Commission’s mandate under section 10(c) of the Human Rights

Commission of Sti Lanka Act, No. 21 of 1996. The said provision empowers the Commission to

‘advise and assist the government in formulating legislation...in furtherance of the promotion and

protection of fundamental rights’.

The proposed Bill's preamble acknowledges that ‘a truth-seeking mechanism, anchored in the right

ofall Sri Lankans to know the truth as an integral part of their right to an effective remedy, will

contribute to the promotion of national unity, peace, rule of law, coexistence, equality with

tolerance and respect for diversity, and reconciliation among the people of Sri Lanka and

nonrecurrence of disharmony and violence...”

‘The Commission acknowledges that the right to truth is a well-established human right under

international law and remains a key pillar of transitional justice. This right may be exercised both

individually and collectively. The Commission accordingly welcomes any initiative that genuinely

and meaningfully seeks to promote such a right. The right to truth, however, must be promoted in

conjunction with the advancement of other pillars of transitional justice: accountability,

reparations, and non-recurrence. Accordingly, and in conjunction with any proposal for a new

truth-seeking mechanism, existing mechanisms, including the Office on Missing Persons and the

Office for Reparations, must be adequately empowered and resourced to fulfil their mandates. We

see that the current Bill makes reference to these institutions and mandates the CTUR to engage

with both as necessary.

In view of strengthening the promotion of transitional justice in Sri Lanka, the Commi

presents the following five observations and recommendations with respect to the proposed Bill,

ge Bdoeo | Mab 8g and etn, emgt - 0 coed i aes

dn cage |. ab Bc 086 060. emce Ok SHEA LE, ae

The proposed CTUR, as comprehensive as it may be, is yet another mechanism among many

such mechanisms previously designed to ascertain the truth concerning serious violations of

human rights committed during the armed conflict in Sri Lanka, We note that victims of such

violations have repeatedly engaged state mechanisms and presented their experiences on a

number of occasions.

For instance, we recall that one such mechanism, the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation

Commission (LLRC), — established 2010, presented numerous constructive

recommendations in its final report published in November 2011. These recommendations

were based on the evidence of hundreds of victims and witnesses of human rights violations,

who came before the LLRC. These victims and witnesses shared their harrowing experiences

with the LLRC and expected that the LLRC’s recommendations based on their complaints

would be implemented. Yet, many of these recommendations are yet to be implemented. It is

imperative, therefore, that the constructive recommendations of past truth-seeking

mechanisms be fully implemented prior to allocating resources towards yet another truth-

seeking mechanism that compels victims and witnesses to recount their traumatic experiences

once again

While observing that implementation of recommendations is prioritised in the Bill, it is

recommended that a high-level committee, similar to that envisaged by Clauses 39 and

40 of the Bill, be immediately established under the Presidential Secretariat, with the

pation of relevant experts and representatives of victim groups and civil society,

to monitor the implementation of all constructive recommendations of previous truth-

seeking mechanisms, including the LLRC. This committee should publish regular

progress reports on the implementation of such recommendations.

‘The Commission appreciates the emphasis placed on the need to know the truth and any effort

towards the goals of unity and reconciliation, However, itis of the opinion that yet another

mechanism that re-victi s affected communities is unlikely to achieve its intended

objectives. It is time for the government to acknowledge the truths that have already been

established by previous mechanisms and facilitate and support the sharing of such truths with

a broader population in fulfilment of the collective right to truth. It is advised, therefore, that

the government begin by accepting the findings and recommendations of previous truth-

seeking mechanisms.

It is recommended that the government carry out programmes that inform the country

as a whole about the findings of previous truth-seeking mechanisms. For instance, these

programmes can feature the integration of such findings into the current education

curriculum and can support writers and artists who engage such findings. Such

programmes can be carried out through already established institutions, such as the

Office for National Unity and Reconeiliation.

Accountability is an important and indispensable corollary of any truth-seeking mechanism.

The discovery and acknowledgment of the truth must not be viewed as an alternative to

accountability for violations and crimes that are revealed through a truth-seeking mechanism.

It is, therefore, imperative that the recommendations of past truth-seeking mechanisms,

relating to accountability, are fully implemented. For example, the LLRC, having received

numerous complaints about enforced disappearances, recommended the investigation of

specific cases where persons who surrendered to state officials during the final stages of the

armed conflict subsequently disappeared, and recommended the prosecution of those

responsible for such disappearances. We note that this recommendation is yet to be

implemented despite the enactment of the International Convention for the Protection of All

Persons from Enforced Disappearance Act, No. 5 of 2018.

Clause 13(zd) of the Bill empowers the CTUR ‘to refer matters to the relevant law

enforcement or prosecuting authorities of Sti Lanka for further investigation and necessary

action, where it appears to the Commission that an offence or offences punishable under the

Penal Code (Chapter 19) or any other law of Sri Lanka has been committed’. However, the

Bill does not contain any specific duty or obligation of the CTUR to identify suspects or

recommend investigations and prosecution of gross human rights violations and grave crimes

in its final report. It is also observed that the proposed CTUR does not include a standing

Investigation Unit with relevant competent, experienced, and qualified investigators,

including those with relevant technical and forensic expertise.

Itis recommended that the interdependence of truth and accountability be meaningfully

integrated into the current transitional justice agenda in Sri Lanka. Given that previous

mechanisms, including the LLRC, have already recommended the investigation and

prosecution of gross violations of human rights and grave crimes, it is recommended that

an effective and independent mechanism for investigation and prosecution of such

violations and crimes be established as a matter of priority. Such a mechanism should

be adequately resourced and should have access to relevant expertise including, where

relevant, international expertise.

According to Clause 12 of the Bill, the mandate of the proposed CTUR is to ‘investigate,

inquire, and make recommendations in respect of complaints or allegations or reports relating

to damage or harm caused to persons or property, loss of life or alleged violation of human

rights anywhere in Sri Lanka, which were caused in the course of, or reasonably connected to,

‘or consequent to the conflict which took place in the Northern and Eastern Provinces during

the period 1983 to 2009, or its aftermath.’ We note that the scope of this mandate is limited

and excludes civil disturbances, including insurrections, and gross human rights violations

and grave crimes, which took place during this period. A large part of Sri Lanka’s

population—especially young persons—were deeply affected by such events. Therefore, such

events ought not to be excluded from the scope of any transitional justice mechanism.

Moreover, the prevailing culture of impunity in Sri Lanka, which the Commission has

repeatedly raised as a major concern, stems from the lack of accountability for gross human

rights violations and grave crimes committed during the armed conflict as well as during such

civil disturbances and insurrections. The commitment to non-recurrence of violence—a key

pillar of transitional justice—cannot be fulfilled unless a more holistic understanding of

impunity is gained, and non-recurrence is ensured through sufficient deterrents.

It is recommended that the scope of transitional justice mechanisms in Sri Lanka

includes both the armed conflict and civil disturbances, including insurrections. The

Political and socioeconomic conditions that underlie and connect the latter to the former

must be part of the truth that the country as a whole reckons with. One of the key

objectives of such mechanisms should be to generate a better understanding of Sri

Lanka’s culture of impunity, and to ensure non-recurrence of violence by holding

perpetrators of gross human rights violations and grave crimes to account. As

contemplated in the Bill with regard to the CTUR’s recommendations, conditions such

as social and economic deprivation, in addition to the vi

rights, which have led to past violence, must also be part of the collective truth regarding

such violence.

5. The promotion of the right to truth should not be understood as a matter of ‘foreign affairs’,

but instead a matter of domestic justi acknowledging the important work carried out

by the Ministry of Foreign (fi regard, the continued association of transitional

justice mechanisms with this Ministry could signal to the citizens of Sri Lanka that these

mechanisms are, by design, primarily connected to Sri Lanka’s foreign relations and

‘engagement of international mechanisms.

Itis recommended that any transitional justice mechanism in Sri Lanka be housed under

the Presidential Secretariat, thereby according to it the highest status and importance.

Thank you.

Yours Sincerely,

niya

A Judge ofthe Supreme Court (Retired)

Stet Chaim

" Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka

Justice L T B Dehideniya

Chairman

Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka

Ce: Hon. Ali Sabry, P.C.

Minister of Foreign Affairs,

Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Republic Building,

Sir Baron Jayathilake Mawatha,

Colombo 01

The Hon, Attorney-General

Attorney General’s Department,

Colombo 01200

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Gazette Extraordinary 09 June 2023 - Relaxing Import RestrictionsDocument27 pagesGazette Extraordinary 09 June 2023 - Relaxing Import RestrictionsAdaderana Online100% (1)

- Clarification by CBSL On Salary HikeDocument1 pageClarification by CBSL On Salary HikeAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Speaker's Office StatementDocument3 pagesSpeaker's Office StatementAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Buddha Sasana, Religious and Cultural Affairs - Press ReleaseDocument3 pagesMinistry of Buddha Sasana, Religious and Cultural Affairs - Press ReleaseAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- CCPI October 2023 by DCSDocument9 pagesCCPI October 2023 by DCSAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Epi Update-Handover 162Document26 pagesCovid-19 Epi Update-Handover 162Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Business November 2023Document3 pagesParliamentary Business November 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Media Release - SLCM202394 - SLC Response To SJB LeadershipDocument4 pagesMedia Release - SLCM202394 - SLC Response To SJB LeadershipDarshana SanjeewaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Month 2023 Report - EnglishDocument23 pagesNutrition Month 2023 Report - EnglishAdaderana Online100% (4)

- Household Survey On Impact of Economic Crisis - 2023Document8 pagesHousehold Survey On Impact of Economic Crisis - 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

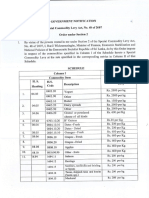

- Special Commodity Levy - GazetteDocument7 pagesSpecial Commodity Levy - GazetteAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Electricity Tariff Revision October 2023 CEBDocument3 pagesElectricity Tariff Revision October 2023 CEBAdaderana Online100% (1)

- Budget 2024-President Ranil Wickremesinghe-Full SpeechDocument210 pagesBudget 2024-President Ranil Wickremesinghe-Full SpeechAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- UGCDocument12 pagesUGCsheain fernandopulleNo ratings yet

- CBSL-Order On Maximum Interest Rates On Sri Lanka LKR Denominated Lending Products.Document4 pagesCBSL-Order On Maximum Interest Rates On Sri Lanka LKR Denominated Lending Products.Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Press Release - Participation of The Employees' Provident Fund in The Domestic Debt Optimisation ProgrammeDocument5 pagesPress Release - Participation of The Employees' Provident Fund in The Domestic Debt Optimisation ProgrammeAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- UN Human Rights ReportDocument16 pagesUN Human Rights ReportAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Gazette Extraordinary 2022-08-26 Water Tariff IncreaseDocument11 pagesGazette Extraordinary 2022-08-26 Water Tariff IncreaseAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Colombo Consumer Price Index CCPI - June 2023Document9 pagesColombo Consumer Price Index CCPI - June 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith - Press Release EnglishDocument3 pagesMalcolm Cardinal Ranjith - Press Release EnglishAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Extraordinary GazetteDocument10 pagesExtraordinary GazetteAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Sectoral Oversightt Committee On National Security-Report On SLTDocument31 pagesSectoral Oversightt Committee On National Security-Report On SLTAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Colombo Consumer Price Index - March 2023Document9 pagesColombo Consumer Price Index - March 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Extraordinary GazetteDocument10 pagesExtraordinary GazetteAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Colombo Consumer Price Index CCPI April 2023Document9 pagesColombo Consumer Price Index CCPI April 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Fake URLs ListDocument3 pagesFake URLs ListAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Consumer Affairs Authority - Gazette Extraordinary No 2327-35Document4 pagesConsumer Affairs Authority - Gazette Extraordinary No 2327-35Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- National Consumer Price Index NCPI March 2023Document8 pagesNational Consumer Price Index NCPI March 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Heat Index Advisory - 16 AprilDocument2 pagesHeat Index Advisory - 16 AprilAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- BASL Media ReleaseDocument2 pagesBASL Media ReleaseAdaderana OnlineNo ratings yet