Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jameson 2004

Uploaded by

GiwrgosKalogirou0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views6 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views6 pagesJameson 2004

Uploaded by

GiwrgosKalogirouCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Symptoms of Theory or Symptoms for Theory?

Fredric Jameson

The notion of an end of theory has been accompanied by announce-

ments of the end of all kinds of other things, which have not been particu-

larly accurate. Let me begin by outlining my conception of what theory is.

I believe that theory begins to supplant philosophy (and other disciplines

as well) at the moment it is realized that thought is linguistic or material

and that concepts cannot exist independently of their linguistic expression.

That is something like a philosophical “heresy of paraphrase,” and it at once

excludes and forestalls a great deal of philosophical and systematic writing

organized around systems or intentions, meanings and criteria of truth and

falsity. Now critique becomes a critique of language and its formulations,

that is to say, an exploration of the ideological connotations of various

formulations, the long shadow cast by certain words and terms, the ques-

tionable worldviews generated by the most impeccable definitions, the ide-

ologies seeping out of seemingly airtight propositions, the moist footprints

of error left by the most cautious movements of righteous arguments. This

is to say that theory—as the coming to terms with materialist language—

will involve something like a language police, an implacable search and de-

stroy mission targeting the inevitable ideological implications of our

language practices; it remains only to say that for theory all uses of language,

including its own, are susceptible to these slippages and oilspills because

there is no longer any correct way of saying it, and all truths are at best

momentary, situational, and marked by a history in the process of change

and transformation. You will already have recognized deconstruction in my

description, and some will wish to associate Althusserianism with it as well.

We can indeed formulate something like an aesthetic of such writing (pro-

vided aesthetic is understood as a rigorous canon of taboos and conven-

Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004)

䉷 2004 by The University of Chicago. 0093–1896/04/3002–0019$10.00. All rights reserved.

403

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

404 Fredric Jameson / Symptoms of/for Theory

tions): its fundamental law would seem to be the exclusion of substantive

statements and positive philosophical propositions. All affirmative posi-

tions, in other words, are flawed and ideological because they reflect our

own personal and class (and race and gender) standpoints.

It is a mistake to assimilate this view of theory to relativism or skepticism

(leading fatally to nihilism and intellectual paralysis); on the contrary, the

struggle for the “rectification” of wording is a well-nigh interminable pro-

cess, which perpetually generates new problems. As for the overall contra-

diction of theory—how to advance the argument without actually saying

anything—it has known a variety of solutions, which can’t be enumerated

here. The single example of the neologism may suffice, the doomed attempt

to outwit the heavy baggage of actually existing language by way of post-

natural innovation. But theory’s eternal enemy, reification, quickly absorbs

and neutralizes the attempt.

What we now have to register (I’m slowly coming to the question of

theory today) is the way in which this view of thinking and writing gradually

annexes large areas of the traditional disciplines, that is to say, traditions in

which outmoded practices of representation—belief in the separation of

words and concepts—still holds sway. I am describing the process of the

expansion of theory in figures of war and domination and imperialism be-

cause theory is of course also yet another characteristic superstructural de-

velopment of late capitalism and thus displays many of the same dynamics

(although in a wholly different political valence). At any rate, what happens

during the period in which theory spreads—and the classical story is well

known: first anthropology borrows its fundamental principles from lin-

guistics, then literary criticism develops the former’s implications in a range

of new practices, which are adapted to psychoanalysis and the social sci-

ences, the law, other cultural disciplines—what happens in this process of

transfer is what I would characterize (keeping to a linguistic mode) as

wholesale translation, the supplanting of one language by another or, better

still, by one kind of language of a whole range of very different ones. What

is called the exhaustion of theory is generally little more than the completion

of this translational appropriation for this or that disciplinary area.

Now clearly there are many other ways of telling this story, which vary

according to one’s disciplinary perspective. I do feel that it has a modernist

dynamic or telos, borrowed from that modernism in the arts that no longer

F re d r i c J a m e s o n is director of the Institute for Critical Theory at Duke

University and a professor of French and comparative literature. Among his

recent books are A Singular Modernity (2002), Brecht and Method (1998), and The

Seeds of Time (1994).

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Winter 2004 405

exists; in other words the dynamic of theory has been the pursuit of the new

and, if not a belief in progress, then at least a confidence that there always

will be something new to replace the various older reified or signed theories

that have been absorbed into and domesticated by the theoretical canon.

Or is there such a thing as a theoretical canon? Is theoretical production not

already postmodern in spirit? Can we distinguish between the modernist

and the postmodernist theoretical production? For the moment, decisions

on questions like this risk lapsing into sheer opinion.

But I do think a brief review of the history of theory is in order, and this

would be my version: a first moment in which the inner structure—the

inner gap or fissure—of the concept as such is explored. This is the moment

often identified as structuralism, in which it becomes clear that concepts

are not autonomous but rather relational—both internally and exter-

nally—and in which their materiality becomes inescapable; in which, in

other words, it slowly begins to dawn on us that concepts are not ideas but

rather words and constellations of words at that.

In a second moment—sometimes called poststructuralism—this dis-

covery mutates as it were into a philosophical problem, namely, that of rep-

resentation, and its dilemmas, its dialectic, its failures, and its impossibility.

Maybe this is the moment in which the problem shifts from words to sen-

tences, from concepts to propositions. At any rate, it is a problem that has

slowly come to subsume all other philosophical issues, revealing itself as an

enormous structure that no one has ever visited in its entirety, but from

whose towers some have momentarily gazed and whose underground bun-

kers others have partially mapped out. Thus, the general issue of represen-

tation is still very much with us today and organizes so to speak the normal

science of theory and its day-to-day practices and guides the writing of its

innumerable reports, which we call articles.

Now we come to a third moment, and it is this one that I believe to be

new and imperfectly explored and the place in which original theory is still

being done today. This is the area of the political, which has always been

the property of the most retrograde academic disciplines and the most bor-

ing and old-fashioned kind of philosophizing. Suddenly these old texts and

the academic frameworks in which they were being read found themselves

transformed beyond recognition by the lightning bolt of a different kind of

philosophico-theoretical opposition, namely, that between the universal

and the particular: an opposition which is not in that form a problem (ex-

cept for an older philosophical discourse) but which immediately shatters

into all kinds of new ones, the “particular” reappearing variously in the

form of the specific, the individual, the singular, and even the virtual, while

a bad universalism hangs over everything like a doomsday cloud and gets

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

406 Fredric Jameson / Symptoms of/for Theory

identified with everything from the state to the commodity form, from re-

pressive sexual norms to the identities of class analysis. This is then not some

problem that can be solved, not an opposition that can be dialectically tran-

scended, but rather a whole new theoretical coding system in which every-

thing that went before must now be reconfigured. Under the tutelary deities

of Machiavelli and Hobbes, and then of Spinoza and Carl Schmitt a whole

new kind of discourse, a genuinely theoretical political theory, emerges, re-

cast in the agonistic structure of Schmitt’s “friend and foe” and finding its

ultimate figure in war. Or at least one should say that war is the ultimate

figure in which the political is revealed; because the latter is also a construc-

tion, a defamiliarization, and a rewriting, a simplification of concrete life

in the form of a new model, I’m tempted to have recourse to Deleuze’s

notion of diagrammatization (which he develops on the occasion of Fou-

cault). Yes, thinking politically means turning representation intodiagrams,

making visible the vectors of force as they oppose and crisscross each other,

rewriting reality as a graph of power centers, movements, and velocities.

Such diagrams are the last avatar of those visual aids that mesmerized the

first structuralisms; they are the latest way to get out of ideas and into a new

form of materialization.

I am personally somewhat distant from this new moment, as I have al-

ways understood Marxism to mean the supersession of politics by econom-

ics; and I therefore want to forecast yet a fourth moment for theory, as yet

on the other side of the horizon. This one has to do with the theorizing of

collective subjectivities, although, because it does not yet theoretically exist,

all the words I can find for it are still the old-fashioned and discredited ones,

such as the project of a social psychology. One wants to think of formula-

tions (and indeed diagrams) for collectivities that are at least as complex

and stimulating as those of Lacan for the individual unconscious. These

structures have certainly been glimpsed in the various explorations of the

social or collective Imaginary in recent years. One feels that the recent phil-

osophical prestige of the Other and otherness is for the most part an ethical

simplification of these realities (save, perhaps, for some suggestions in the

Sartre of the Critique). Meanwhile, subaltern studies comes at all this from

yet another direction, and Deleuze (or Deleuze and Guattari), resolutely

post-Cartesian, offers a variety of new ways to map a whole range of col-

lective phenomena. But it is in the nature of the beast (the human animal)

to draw back from such openings; we still don’t want to hear anything about

social class; and new theoretical fashions like Giorgio Agamben’s idea of

naked life are at once read as metaphysical or existential statements or at

worst enlisted to prove—being a kind of zero degree—that the collective

does not exist (instead of being grasped as the identification of a new col-

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Winter 2004 407

lective planet or quark). But it is not very satisfying to talk about fields that

do not (yet) exist.

So let me turn in conclusion to literary criticism, something that has also

been pronounced dead from time to time. If so, that may be because, on

the one hand, we now have as many different methods and techniques as

any object could possibly require or, on the other hand, because of the gen-

eral volatilization of the old-fashioned work of art or if you prefer the death

of literature itself. Even literary history has accumulated impressive quan-

tities of research, which may largely suffice for a time even though the his-

torical reevaluation of this data remains as interesting a theoretical problem

as all postmodern historiography. Meanwhile there flourishes a kind of in-

sider trading on the most advanced textual sensations, from Memento to

hip-hop; but these are all textual objects, and it is pernicious to distinguish

between literature and cultural studies in the pejorative ways we are familiar

with. On all such textual criticism I want to quote a recent writer, Cesare

Casarino, who comments as follows on the old question, What is literary

criticism? “The question could have been posed differently. As if inquiring

after the health of a loved one who has been very ill for a long time, and

who has been absent from one’s daily life but all the more present because

of it in one’s daily thoughts, one could have asked: how is literary criticism?”

His answer, which I would be inclined to endorse, is what he calls philo-

poeisis, which names, he says, “a certain discontinuous and refractive in-

terference between philosophy and literature.”1 But this also names theory,

I believe.

I want to come at the question a little differently, however, and to defend

the position that literary criticism is or should be a theoretical kind of symp-

tomatology. Literary forms (and cultural forms in general) are the most

concrete symptoms we have of what is at work in that absent thing called

the social. But the idea of a symptom is often misunderstood as encouraging

a vulgar-sociological or content approach to works of art. I suppose that at

this point we could read all of Adorno’s aesthetic writings onto the record

as the supreme illustration of the intent to coordinate inside and outside

and to grasp the “windowless monad” of autonomous form as a social and

historical symptom. It might be worth adding that as much or even more

than content, form is itself the bearer of ideological messages and exists as

a social fact. To be sure, the technical questions about such delicate and

complicated coordinations are at the very center of literary theory itself.

Suffice it to say that works of the past afford all kinds of uniquely aesthetic

1. Cesare Casarino, Modernity at Sea: Melville, Marx, Conrad in Exile (Minnesota, 2002),

p. xiii.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

408 Fredric Jameson / Symptoms of/for Theory

openings onto their own moment; while those of the present include all

kinds of coded data on our own—that blind spot of the present from which

we are in many ways the farthest. What we tend to neglect, however, are the

utopian projections works of past and present alike offer onto a future oth-

erwise sealed from us.

But this account of the tasks of theory and criticism has so far left out

the most distinctive feature of our own (postmodern) times, at least as far

as the aesthetic is concerned. This is very precisely that volatilization of the

individual work or text I mentioned earlier, a development that if taken

seriously determines a considerable shift in perspective and in critical prac-

tices. For is it clear that the questions raised by literary method are not

nearly so urgent or timely when significant literature ceases to be produced

or rather, putting it in a different way, when the center of gravity of some

putative “system of the fine arts” moves away from those of language and

displaces the ideal of poetic language that was central during the modernist

period?

This is why it has seemed to me that today, in postmodernity, our objects

of study consist less in individual texts than in the structure and dynamics

of a specific cultural mode as such, beginning with whatever new system

(or nonsystem) of artistic and cultural production replaced the older one.

It is now the cultural production process (and its relation to our peculiar

social formation) that is the object of study and no longer the individual

masterpiece. This shifts our methodological practice (or rather the most

interesting theoretical problems we have to raise) from individual textual

analysis to what I will call mode-of-production analysis, a formula I prefer

to those that continue to use the word culture in something of an anthro-

pological sense.

Culture in that sense is the ideological property of Samuel Huntington

and the people he has inspired. Indeed, the very war he inspired is the con-

text in which I would defend this methodological proposal because I think

that it is only in the light of the study of late capitalism as a system and a

mode of production that we can understand the things going on around us

today. Those things are not merely the acts of a fundamentalist reactionary

group around an unelected president—something that might at best be at-

tributed to sheerest accident or national bad luck; they are part and parcel

of our system, and understanding cultural production today is not the worst

way of trying to understand that system and the possibilities it may offer

for radical or even moderate change.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 25, 2016 20:01:56 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- The University of Chicago PressDocument7 pagesThe University of Chicago Presscottchen6605No ratings yet

- Symptoms of Theory or Symptoms For TheoryDocument6 pagesSymptoms of Theory or Symptoms For TheoryyusufcaliskanNo ratings yet

- Demarcation and Demystification: Philosophy and Its LimitsFrom EverandDemarcation and Demystification: Philosophy and Its LimitsNo ratings yet

- The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic MetaphysicsFrom EverandThe One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic MetaphysicsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Our Knowledge of the External World as a Field for Scientific Method in PhilosophyFrom EverandOur Knowledge of the External World as a Field for Scientific Method in PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- The Political Philosophy of Poststructuralist AnarchismFrom EverandThe Political Philosophy of Poststructuralist AnarchismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The End of Progress: Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical TheoryFrom EverandThe End of Progress: Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical TheoryNo ratings yet

- Intro: Experience and Critique. Placing Pragmatism in Modern PhilosophyDocument17 pagesIntro: Experience and Critique. Placing Pragmatism in Modern PhilosophyManuel Salvador Rivera EspinozaNo ratings yet

- The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismFrom EverandThe Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian FormalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Reflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseFrom EverandReflecting on Reflexivity: The Human Condition as an Ontological SurpriseNo ratings yet

- History of Modern Philosophy: From Nicolas of Cusa to the Present TimeFrom EverandHistory of Modern Philosophy: From Nicolas of Cusa to the Present TimeNo ratings yet

- All under Heaven: The Tianxia System for a Possible World OrderFrom EverandAll under Heaven: The Tianxia System for a Possible World OrderNo ratings yet

- Different Types of FallaciesDocument9 pagesDifferent Types of FallaciesJamela TamangNo ratings yet

- The Mark of Theory: Inscriptive Figures, Poststructuralist PrehistoriesFrom EverandThe Mark of Theory: Inscriptive Figures, Poststructuralist PrehistoriesNo ratings yet

- Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and PraxisFrom EverandBeyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and PraxisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of ThinkingFrom EverandPragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of ThinkingRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- International Relations and the Challenge of Postmodernism: Defending the DisciplineFrom EverandInternational Relations and the Challenge of Postmodernism: Defending the DisciplineNo ratings yet

- Fredric Jameson, ValencesDocument624 pagesFredric Jameson, ValencesIsidora Vasquez LeivaNo ratings yet

- Valences of The Dialectic2Document625 pagesValences of The Dialectic2Eric OwensNo ratings yet

- El Lugar de La TeoriaDocument0 pagesEl Lugar de La TeoriaCarlitos Mala EspinaNo ratings yet

- Balibar - Sub Specie UniversitatisDocument14 pagesBalibar - Sub Specie Universitatisromenatalia9002No ratings yet

- Freedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyFrom EverandFreedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyNo ratings yet

- The Modern Political Tradition: Hobbes to Habermas (Transcript)From EverandThe Modern Political Tradition: Hobbes to Habermas (Transcript)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Justifying Sociological Knowledge From Realism To InterpretationDocument30 pagesJustifying Sociological Knowledge From Realism To InterpretationGallagher RoisinNo ratings yet

- Foucault Politics DiscourseDocument30 pagesFoucault Politics Discoursepersio809100% (1)

- The Two Sociologies and the Distinction Between Description and TheoryDocument20 pagesThe Two Sociologies and the Distinction Between Description and TheoryPedro Cárcamo PetridisNo ratings yet

- Essays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationFrom EverandEssays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationNo ratings yet

- Philosophy as the Logic of ScienceDocument15 pagesPhilosophy as the Logic of SciencePedro PizzuttiNo ratings yet

- Plato and the Other Companions of Sokrates: Complete Edition - The Philosophy and History of Ancient GreeceFrom EverandPlato and the Other Companions of Sokrates: Complete Edition - The Philosophy and History of Ancient GreeceNo ratings yet

- Interpretation Radical but Not Unruly: The New Puzzle of the Arts and HistoryFrom EverandInterpretation Radical but Not Unruly: The New Puzzle of the Arts and HistoryNo ratings yet

- Christopher Norris On Truth and Meaning Language, Logic and The Grounds of Belief 2006Document214 pagesChristopher Norris On Truth and Meaning Language, Logic and The Grounds of Belief 2006Paola AlejandraNo ratings yet

- The Principle of DeterminationDocument16 pagesThe Principle of DeterminationSo BouNo ratings yet

- Loving the World Appropriately: Persuasion and the Transformation of SubjectivityFrom EverandLoving the World Appropriately: Persuasion and the Transformation of SubjectivityNo ratings yet

- Nordicom ReviewDocument9 pagesNordicom ReviewIvánJuárezNo ratings yet

- Viva A CriseDocument16 pagesViva A CrisethiagoNo ratings yet

- Critical Theory (From International Encycl - J. J. RyooDocument6 pagesCritical Theory (From International Encycl - J. J. RyookeithholdichNo ratings yet

- The End of TheoristsDocument24 pagesThe End of TheoristsHarumi FuentesNo ratings yet

- Definitions / 7: 8 Critical Theory and Science FictionDocument2 pagesDefinitions / 7: 8 Critical Theory and Science FictionMagali BarretoNo ratings yet

- On Structure, by Etienne BalibarDocument8 pagesOn Structure, by Etienne BalibarChristinaNo ratings yet

- Structuralism: A Destitution of The Subject?Document21 pagesStructuralism: A Destitution of The Subject?Alex SNo ratings yet

- Berlant - Critical Inquiry, Affirmative CultureDocument8 pagesBerlant - Critical Inquiry, Affirmative CultureScent GeekNo ratings yet

- How Periods Erase HistoryDocument6 pagesHow Periods Erase HistoryGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Προκόπης ΠαπαστράτηςDocument5 pagesΠροκόπης ΠαπαστράτηςGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Failing Natural Languages, Gerard GenetteDocument66 pagesFailing Natural Languages, Gerard GenetteGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Peter Dews, Resituating the PostmodernDocument9 pagesPeter Dews, Resituating the PostmodernGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Passion As PerformanceDocument8 pagesPassion As PerformanceGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Admirimg AutonomyDocument7 pagesAdmirimg AutonomyGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Edward ConzeDocument559 pagesEdward ConzeGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Greek Art in The European ContextDocument23 pagesGreek Art in The European ContextGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Trotsky's Advice To Young MarxistsDocument2 pagesTrotsky's Advice To Young MarxistsGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- The Interpretations of Art: Part III, Romanticism + ConclusionDocument120 pagesThe Interpretations of Art: Part III, Romanticism + ConclusionPeter Bornedal100% (1)

- Malcolm Bradnury, ModernismDocument13 pagesMalcolm Bradnury, ModernismGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Zigmunt Bauman, The Left As The Counter Culture of ModernityDocument13 pagesZigmunt Bauman, The Left As The Counter Culture of ModernityGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Revolution in Religious Language - The Relevance of Julia KristeDocument196 pagesRevolution in Religious Language - The Relevance of Julia KristeGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- The Uprising BifoDocument18 pagesThe Uprising BifoGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Law in Action Understanding Canadian LawDocument19 pagesLaw in Action Understanding Canadian LawGloria VelezNo ratings yet

- Gesta HahnDocument13 pagesGesta Hahngabriele guadagninoNo ratings yet

- Shut Up and DanceDocument1 pageShut Up and DanceJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Coloring Oil Pastels 1Document14 pagesColoring Oil Pastels 1Myo AungNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter3Document36 pages09 Chapter3Sathish RajakumarNo ratings yet

- Mozart Symphony N. 39 Eb Major Finale Violin 1Document1 pageMozart Symphony N. 39 Eb Major Finale Violin 1RoyNo ratings yet

- 4 Periods in Art History (Part 1)Document55 pages4 Periods in Art History (Part 1)Kiel JohnNo ratings yet

- Writing Sample: Lesson Plan On Motown ForDocument16 pagesWriting Sample: Lesson Plan On Motown ForbranstltNo ratings yet

- ART APPRECIATION Lesson IIDocument10 pagesART APPRECIATION Lesson IICelane FernandezNo ratings yet

- Region I Contemporary Arts AssessmentDocument4 pagesRegion I Contemporary Arts AssessmentChristine Manjares - OañaNo ratings yet

- Hira Sabir... 2nd Wave FeminismDocument21 pagesHira Sabir... 2nd Wave FeminismHira Sabir100% (1)

- Agatha Eng LenamastericaDocument12 pagesAgatha Eng LenamastericaJirafa GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Hero Kids - GM ScreenDocument1 pageHero Kids - GM ScreenGarry MossNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Art AppreciationDocument12 pagesModule 6 Art AppreciationJohn Henry TampoyNo ratings yet

- Can't My Eyes Off You Flute SoloDocument14 pagesCan't My Eyes Off You Flute SoloAshley Tan100% (3)

- Great Extrapolations: Archive - TodayDocument5 pagesGreat Extrapolations: Archive - TodayRobertt MosheNo ratings yet

- MAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 7: New Music (Chance Music)Document11 pagesMAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 7: New Music (Chance Music)Albert Ian Casuga100% (1)

- Uniden Beartracker 800 BCT-7 Owners ManualDocument122 pagesUniden Beartracker 800 BCT-7 Owners Manualsuperflypecker0% (1)

- G9 Tos Template - 3RD QuarterDocument3 pagesG9 Tos Template - 3RD QuarterMARIA REYNALYN MAGTIBAYNo ratings yet

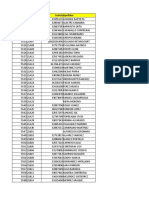

- Base de Datos Liceo 2021-2022Document36 pagesBase de Datos Liceo 2021-2022yefersonNo ratings yet

- Religion, Race and Rhetoric in Rizal's TravelsDocument12 pagesReligion, Race and Rhetoric in Rizal's TravelsLove LetterNo ratings yet

- Learning From Beirut From Modernism To ContemporarDocument8 pagesLearning From Beirut From Modernism To ContemporarnevenapreNo ratings yet

- Only The Good Die YoungDocument8 pagesOnly The Good Die Youngjon_scribd2372No ratings yet

- The Technique of The Color Wood-CutDocument27 pagesThe Technique of The Color Wood-CutAlessandro SeveroNo ratings yet

- Prufrock" Analysis: Eliot's "Love SongDocument12 pagesPrufrock" Analysis: Eliot's "Love SongÅmîť MâńďáľNo ratings yet

- O RomeoDocument1 pageO Romeohotcool_babe4u694u100% (1)

- ECO Friendly Architecture: Assignment - 4Document7 pagesECO Friendly Architecture: Assignment - 4Shalaka DhandeNo ratings yet

- Mahasthangarh: Ancient Capital of PundravardhanaDocument6 pagesMahasthangarh: Ancient Capital of PundravardhanaIrfan Ul HaqNo ratings yet

- Fame Celebrity and Performance - 2014Document416 pagesFame Celebrity and Performance - 2014Merve ÖzdağdağNo ratings yet

- Origami Eyebrows WatcherDocument1 pageOrigami Eyebrows WatcheralexbaqueroNo ratings yet