Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S0002817723003173 Main

Uploaded by

olga orbaseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 S0002817723003173 Main

Uploaded by

olga orbaseCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Trial

School-based caries prevention and the impact

on acute and chronic student absenteeism

Ryan Richard Ruff, PhD, MPH; Rami Habib, BSc; Tamarinda Barry Godín, DDS, MPH;

Richard Niederman, DMD

ABSTRACT

Background. Poor oral health is significantly associated with absenteeism, contributing to millions

of lost school hours per year. The effect of school-based dental programs that address oral health

care inequities on student attendance has not yet been explored.

Methods. CariedAway was a longitudinal, cluster-randomized, noninferiority trial of minimally

invasive medicines for caries used in a school-based program. We extracted data on school

absenteeism and chronically absent students from publicly available data sets for years before,

during, and after program onset (2016-2021). Total absences and the proportion of chronically

absent students were modeled using multilevel mixed-effects linear and 2-limit tobit regression,

respectively.

Results. In years in which treatment was provided through a school-based caries prevention

program, schools recorded approximately 944 fewer absences than in nontreatment years (95% CI,

–1,739 to –149). Averaged across all study years, schools receiving either treatment had 1,500 fewer

absences than comparator schools, but this was not statistically significant. In contrast, chronic

absenteeism was found to significantly decrease in later years of the program (b, –.037; 95% CI,

–.062 to –.011). Excluding data for years affected by COVID-19 removed significant associations.

Conclusions. Although originally designed to obviate access barriers to critical oral health care,

early integration of school-based dental programs may positively affect school attendance. However,

the observed effects may be due to poor reliability of attendance records resulting from the closing of

school facilities in response to COVID-19, and further study is needed.

Practical Implications. School-based caries prevention may also improve educational outcomes,

in addition to providing critical oral health care. This clinical trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.

gov. The registration number is NCT03442309.

Key Words. Oral health; caries prevention; education; academic performance; absenteeism.

JADA 2023:154(8):753-759

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2023.05.007

C

aries is the most prevalent noncommunicable disease in the world and disproportionately

affects children from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those from low-income or minority

families.1 Children with poor oral health face numerous barriers to academic success

including missed school days, lower test performance, and difficulty paying attention; in addition,

poor oral health affects functional and psychological behavior.2,3 In 2019, a systematic review

concluded that poor oral health was associated with school performance and student absenteeism.4

In contrast, children covered by Medicaid (a government-sponsored health insurance program and

primary source of dental coverage for low-income children) who receive comprehensive screening

services early in life may achieve higher academic performance.5

Copyright ª 2023

Despite the potential health and cognitive benefits of early childhood oral health care, high- American Dental

risk children often have lower dental service use rates. 6-8 Historical data from multiple states Association. This is an

indicate that more than 75% of children covered under Medicaid fail to receive required dental open access article under

the CC BY-NC-ND license

services.9 One in 4 children does not see a dentist at all.9 In part to address this unmet need,

(http://creativecommons.

multiple federal agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recom- org/licenses/by-nc-nd/

mend school-based dental programs, which can provide a range of effective preventive and 4.0/).

JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023 753

therapeutic services to increase access to essential oral health care10 and reduce the burden of

disease.11,12

Use of school-based health programs providing medical, dental, mental, and vision services may

positively affect student attendance.13,14 School dental programs can reduce the need for unplanned

dental services that lead to increased absenteeism.15 They may also improve quality of life,16 which

has similarly been shown to affect school performance.17 CariedAway was a pragmatic cluster-

randomized trial of treatments for caries provided through a school-based program.18 Conducted

in predominantly low-income minority urban students, a secondary objective of CariedAway was to

assess the effect of a school-based oral health care program on educational performance.

METHODS

Design and participants

CariedAway was a longitudinal, cluster-randomized, noninferiority pragmatic trial of minimally

invasive interventions for caries implemented in schools. The study was conducted in New York,

New York, primary schools from 2018 through 2023, received ethics approval from the New York

University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (i17–00578). A trial protocol was

previously published.18 The primary objective of CariedAway was to assess the noninferiority of

silver diamine fluoride (SDF) and fluoride varnish compared with dental sealants, the standard of

care, when used in a school-based oral health care program. Clinical outcomes included caries arrest

at 2 years and caries incidence at 4 years. In addition, the trial explored the effectiveness of

registered nurses compared with dental hygienists in the provision and the effect of SDF, the impact

on oral health–related quality of life, and the impact on school performance. CariedAway was a

mobile school-based program: clinicians would visit each school sequentially, provide treatments

using mobile equipment, and then move to the next school once patient care was completed.

Patient recruitment

Participant recruitment followed a 2-stage process. First, any school with at least a 50% Hispanic or

Latino or Black student population and with at least 80% receiving free and reduced-cost lunches

was eligible for inclusion. Second, schools were randomized to treatments and any child in enrolled

schools who provided parental informed consent, child assent, and spoke English was enrolled.

Interventions

Schools were block-randomized, using a random number generator, to 1 of 2 conditions: an

experimental treatment consisting of fluoride varnish (5% sodium fluoride) (PreviDent; Col-

gate) applied to all teeth and a 38% SDF solution (2.24 fluoride ion mg/dose) (Advantage

Arrest; Elevate Oral Care) applied to any asymptomatic cavitated lesions and on all pits and

fissures of premolars and molars, and an active comparator consisting of the same fluoride

varnish application, glass ionomer sealants (GC Fuji IX; GC) placed on all pits and fissures of

premolars and molars, and atraumatic restorations on any frank asymptomatic cavitations.

A single drop of SDF solution was dispensed into a disposable mixing well and applied with a

microbrush, followed by air drying for a minimum of 60 seconds. For dental sealants, cavity

conditioner was first applied to pits and fissures for 10 seconds followed by application of glass

ionomer via the finger sweep technique, digitally applied until closed margins were achieved.

Treatments were provided in a private, dedicated room in each school using mobile dental

equipment. Treatments in the SDF arm were provided by either dental hygienists or registered

medical nurses, whereas sealants and atraumatic restorations were applied by dental hygienists. All

care was provided under the supervision of a licensed pediatric dentist. Across all schools, the total

average time that participants were outside of class to receive treatment was 25 minutes.

Comparator schools

For this analysis, a subset of schools that did not receive a treatment assignment was included. This

group consisted of schools that were enrolled in stage 1 of the CariedAway recruitment process but

ABBREVIATION KEY did not proceed to stage 2. These schools served as nonrandomized counterfactuals, in that they

NA: Not applicable. met all study inclusion criteria and were found in the same geographic area, but they were not

SDF: Silver diamine fluoride. randomized and did not receive treatment.

754 JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023

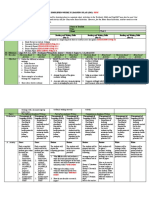

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for absenteeism and chronically absent students, by year.

YEAR SILVER DIAMINE FLUORIDE SCHOOLS SEALANT SCHOOLS NO TREATMENT

Days Missed, Chronically Days Missed, Chronically Days Missed, Chronically

Mean (SD) Absent. % (SD) Mean (SD) Absent. % (SD) Mean (SD) Absent. % (SD)

2016-2017 7,600.53 (3,966.18) 33.99 (5.64) 7,200.33 (3,326.40) 31.81 (12.82) 8,221.85 (3,287.16) 36.92 (8.97)

2017-2018 8,360.41 (4,735.45) 36.64 (5.74) 7,373.76 (3,122.62) 33.15 (12.18) 8,275.77 (3,278.24) 40.59 (8.04)

2018-2019 7,988.44 (4,533.40) 39.01 (10.02) 7,276.10 (3,043.91) 33.86 (13.20) 7,995.85 (2,965.69) 40.28 (7.73)

2019-2020 4,718.72 (2,300.48) 34.03 (7.42) 4,352.48 (1,767.06) 31.81 (11.38) 4,606.54 (1,773.50) 35.52 (9.22)

2020-2021 7,660.28 (3,677.60) 36.71 (12.53) 7,933.95 (3,859.62) 37.61 (14.74) 8,089.39 (3,616.80) 39.1 (15.13)

Data sources and outcomes

Attendance rates for each included school were obtained for school years 2016 through 2021 from

the New York City Department of Education. Student attendance is attributed to the school each

student attended at the time. If a student changed schools, attendance was attributed to multiple

schools. Data were extracted for total days present, total days absent, overall average school

attendance, and the proportion of children classified as chronically absent. Chronic absenteeism was

defined by the New York State Department of Education as any student with a total attendance of

90% or less across all school days (minimum enrollment threshold of 10 days).

Statistical analysis

Data were ordered sequentially by school and year of study. Descriptive statistics for outcomes and

select independent variables were produced overall and by treatment group. Absenteeism was

modeled using mixed-effects linear regression, and the proportion of chronically absent students

using 2-limit mixed-effects tobit regression. Our first model (model 1) was a single-group

analysis defined as yt ¼ b0 þ b1tt þ b2xt þ b3xttt, where t is the overall time since the start of

CariedAway, x is a dummy variable indicating onset of the intervention (for example, signifying a

change from a nonintervention period to an intervention period and vice versa), and xt is their

interaction. Outcome variables (y) included the total number of days absent for each school and the

percentage of students who were chronically absent, and sample regression coefficients (b) represent

estimated effects. Multiple treatment onsets were possible. Subsequent models introduced an

additional parameter, z, representing the treatment type provided in each school (model 2), and a

series of treatment-specific interaction terms including the treatment-time interaction, treatment-

intervention onset, and a 3-level interaction between treatment, time, and intervention onset,

defined as yt ¼ b0 þ b1tt þ b2xt þ b3xttt þ b4z þ b5ztt þ b6zxt þ b7zxttt (model 3). Models were first

run in schools receiving either SDF or sealant treatment (models 1a, 2a, and 3a) and then inclusive

of comparator schools, which did not receive treatment, by modifying the dummy indicator for

treatment as any treatment vs no treatment (models 1b, 2b, and 3b). Schools were included as

random intercepts. As a final analysis, we excluded the 2019 through 2020 school year, which was

partially conducted virtually because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and may have biased

the results.

RESULTS

When restricted to schools that received treatment in CariedAway, our data included 193 yearly

observations across 39 schools. When adding comparator schools, results reflected 52 schools and

258 yearly observations. The average student enrollment per school was 166. The yearly recorded

days absent and proportion of students chronically absent are shown in Table 1.

Results for total days absent (Table 2) and chronic absenteeism (Table 3) include models for

schools receiving SDF vs those receiving dental sealants (models 1a, 2a, and 3a) and then any

treatment vs no-treatment schools (models 1b, 2b, and 3b). For total days absent, there was a

consistent reduction in school absence in years in which treatment was provided (x indicator) as

well as an increased effect when treatment was provided in later school years (xt indicator).

For example, model 2b with all schools included shows a predicted reduction of 883.5 (95% CI,

–1,697.0 to –69.7) missed school days in years in which treatment was provided with an additional

JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023 755

Table 2. Model results for total school absences.*

VARIABLE MODEL 1 MODEL 2 MODEL 3

1a† 1b‡ 2a§ 2b{ 3a# 3b**

††

t , 95% CI 137.8 –25.2 138.0 –24.8 63.2 –418.3 a

(–33.1 to 308.8) (–180.8 to 130.4) (–32.9 to 308.9) (–180.5 to 131.0) (–198.3 to 324.8) (–699.7 to –136.9)

x‡‡, 95% CI –945.2b –879.9b –946.0b –883.5b –1,037.0b –943.9b

(–1,698.0 to 192.0) (–1,692.0 to –67.3) (–1,699.0 to –192.8) (–1,697.0 to –69.7) (–2,064.0 to –10.5) (–1,739.0 to –149.1)

xt, 95% CI –1,607.0a –1,437.0a –1,609.0a –1,437.0a –1,135.0b –1,608.0a

(–2,337.0 to –877.9) (–2,219.0 to –654.7) (–2,339.0 to –879.7) (–2,219.0 to 655.1) (–2,060.0 to –210.1) (–2,378.0 to –837.9)

z§§, 95% CI NA{{ NA –534.2 154.7 –745.2 –1,505.0

(–2,554.0 to 1,486.0) (–1,802.0 to 2,111.0) (–2,984.0 to 1,493.0) (–3,699.0 to 689.6)

zt, 95% CI NA NA NA NA 125.4 555.6a

(–217.4 to 468.1) (221.4 to 889.9)

zx, 95% CI NA NA NA NA 4,129.0 NA

(–1,535.0 to 9,792.0)

zxt, 95% CI NA NA NA NA –1,232.0 NA

(–2,724.0 to 259.0)

Constant, 95% CI 7,238a 7,632a 7,526a 7,515a 7,650a 8,744a

(6,120.0 to 8,355.0) (6,676.0 to 8,587.0) (5,968.0 to 9,084.0) (5,759.0 to 9,271.0) (5,998.0 to 9,302.0) (6,844.0 to 10,645.0)

Observations, No. 193 258 193 258 193 258

Schools, No. 39 52 39 52 39 52

* Superscript letters indicate level of statistical significance ( P < .01, P < .05). † Model 1a: Time only, no comparators. ‡ Model 1b: Time only, with comparators (silver

a b

diamine fluoride [SDF] plus sealant schools plus no treatment). § Model 2a: Multigroup, SDF vs sealant schools. { Model 2b: Multigroup, with comparators (SDF plus

sealant schools vs no treatment). # Model 3a: Full model, SDF vs sealant schools. ** Model 3b: Full model, with comparators (higher interactions removed). †† t:

School year. ‡‡ x: Time varying (treatment year). §§ z: Treatment. {{ NA: Not applicable.

reduction of 1,437.0 days (95% CI, –2,219.0 to –655.1) if treatment was provided in later years.

Including all schools and relevant predictors (model 3b), there was an additional nonsignificant

overall reduction in missed school days in schools that ever received treatment vs schools that did

not (b, –1,505.0; 95% CI, –3,699.0 to 689.6), but this gap was significantly reduced over time (b,

555.6; 95% CI, 221.4 to 889.9). Indicators for the treatment-treatment time and treatment-

treatment time-overall time variables were perfectly collinear as comparator schools never

received treatment and were therefore removed from the final model.

For the proportion of enrolled schoolchildren who were chronically absent, single-group

models (Table 3, models 1a and 1b) indicated that there was a significant yearly increase of

approximately 1% in the proportion of chronically absent students each year and a significant

3% decrease for the interaction between school year and whether the school received treat-

ment that year. Multigroup models with and without comparator schools showed a nonsig-

nificant reduction in chronic absenteeism for SDF vs sealant schools (model 2a) and any

treatment vs no treatment (model 2b). Overall model results (model 3b, inclusive of

comparator schools) suggested that there was an approximate 3.5% decrease in chronic

absenteeism when treatment was provided in later years. There was also a nonsignificant (P ¼

.054) decrease of 7% in schools receiving treatment compared with control schools, but this

effect fell by 1% over time.

Results when excluding data from the 2019 through 2020 school year removed the effect

of treatment in a given year. There remained an overall reduction in days absent when

comparing treated schools with untreated schools, but this effect was not statistically significant

(Table 4, models 1 and 2). Similar results were found for chronically absent students, with a

nonsignificant reduction in the chronically absent population in treated schools (Table 4,

models 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

In addition to school absences resulting from dental pain or infection, acute or unplanned oral

health care contributes more than 30 million hours of missed school per year.19 Although school-

based dental programs were developed to treat and prevent oral diseases in children who lack access

756 JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023

Table 3. Model results for the proportion of chronically absent students.*

VARIABLE MODEL 1 MODEL 2 MODEL 3

1a† 1b‡ 2a§ 2b{ 3a# 3b**

††

t , 95% CI 0.0114 a

0.00766 a

0.0114 a

0.00757 a

0.00625 –0.00184

(0.00542 to 0.0174) (0.00254 to 0.0128) (0.00543 to 0.0174) (0.00245 to 0.0127) (–0.00296 to 0.0155) (–0.0112 to 0.00751)

x‡‡, 95% CI 0.00200 0.00268 0.00194 0.00343 0.00846 0.00200

(–0.0244 to 0.0284) (–0.0240 to 0.0294) (–0.0245 to 0.0283) (–0.0233 to 0.0302) (–0.0277 to 0.0446) (–0.0244 to 0.0284)

xt, 95% CI –0.0369a –0.0329b –0.0370a –0.0328b –0.0328b –0.0369a

(–0.0624 to –0.0113) (–0.0586 to –0.00723) (–0.0626 to –0.0114) (–0.0585 to –0.00715) (–0.0654 to –0.00026) (–0.0624 to –0.0113)

z§§, 95% CI NA{{ NA –0.0283 –0.0285 –0.0498 –0.0681c

(–0.0900 to 0.0334) (–0.0890 to 0.0319) (–0.120 to 0.0205) (–0.137 to 0.00108)

zt, 95% CI NA NA NA NA 0.00885 0.0133b

(–0.00322 to 0.0209) (0.00216 to 0.0244)

zx, 95% CI NA NA NA NA 0.00758 NA

(–0.192 to 0.207)

zxt, 95% CI NA NA NA NA –0.00643 NA

(–0.0589 to 0.0461)

Constant, 95% CI 0.322a 0.340a 0.338a 0.361a 0.350a 0.391a

(0.287 to 0.358) (0.310 to 0.370) (0.289 to 0.386) (0.307 to 0.416) (0.298 to 0.402) (0.331 to 0.451)

Observations, No. 193 258 193 258 193 258

Schools, No. 39 52 39 52 39 52

* Superscript letters indicate level of statistical significance ( P < .01, P < .05, P < .1). † Model 1a: Time only, no comparators. ‡ Model 1b: Time only, with

a b c

comparators (silver diamine fluoride [SDF] plus sealant schools plus no treatment). § Model 2a: Multigroup, SDF vs sealant schools. { Model 2b: Multigroup, with

comparators (SDF plus sealant schools vs no treatment). # Model 3a: Full model, SDF vs sealant schools. ** Model 3b: Full model, with comparators (higher

interactions removed). †† t: School year. ‡‡ x: Time varying (treatment year). §§ z: Treatment. {{ NA: Not applicable.

Table 4. Model results for absences (models 1 and 2) and chronically absent students (models 3 and 4), excluding remote learning years.*

VARIABLE MODEL 1 MODEL 2 MODEL 3 MODEL 4

†

t , 95% CI 58.01 (–56.19 to 172.20) 68.75 (–48.15 to 185.70) a

0.00795 (0.00244 to 0.0135) a

0.00912 (0.00353 to 0.0147)

‡

x , 95% CI 32.5 (–597.1 to 662.0) 127.3 (–541.6 to 796.3) –0.00631 (–0.0365 to 0.0238) 0.00431 (–0.0275 to 0.0362)

z , 95% CI

§

–550.7 (–2,703.0 to 1,601.0) –545.0 (–2,695.0 to 1,605.0) –0.0363 (–0.0983 to 0.0256) –0.0357 (–0.0975 to 0.0261)

xt, 95% CI NA{ –277.8 (–949.1 to 393.5) NA –0.0305b (–0.0625 to 0.00142)

Constant, 95% CI 7,977a (6,086 to 9,868) 7,946a (6,055 to 9,837) 0.369a (0.313 to 0.425) 0.366a (0.310 to 0.422)

Observations, No. 206 206 206 206

Schools, No. 52 52 52 52

* Superscript letters indicate level of statistical significance ( P < .01, P < .1). † t: School year. ‡ x: Time varying (treatment year). { NA: Not applicable. § z: Treatment.

a b

to traditional oral health care,20 their early integration may likewise improve educational perfor-

mance. The CariedAway project provided both comprehensive dental screenings or examinations

and treatment services for untreated caries, supporting preliminary analyses of early school-based

dental interventions on academic outcomes. We conclude that school-based dental programs

may improve school attendance and when implemented longitudinally may decrease the prevalence

of children who are chronically absent. However, we are unable to discern whether effects are

motivated by the impact of COVID-19 on traditional academic instruction.

Prior research suggests that the use of school-based health centers positively affects classroom

attendance and seat time, reflecting the complex role of child health in education.21,22 Our findings

indicate that school-based oral health care may reduce student absenteeism, but the changes in

school operations due to COVID-19 could bias results. Inclusive of all years, there was an average

reduction of 940 missed school days in years that treatment was provided. There were also no

JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023 757

differences in absenteeism when comparing schools receiving treatment with either SDF or dental

sealants. For this latter finding, prior data from CariedAway indicated that the clinical effectiveness

of SDF was noninferior to that of dental sealants when used in a school-based program, with nearly

identical rates of disease prevention over time.11 As both treatments in the CariedAway project had

similar impact, nondifferential effects on secondary outcomes, such as absenteeism, may be

expected.

Many schools participating in the CariedAway program received treatment during the 2019

through 2020 school year; as a result, the marginal effect of treatment may be biased due to the

impact of COVID-19. Schools in New York, New York, closed educational facilities and

transitioned to remote learning on March 15, 2020, and the final one-third of the school year

was conducted virtually. On the one hand, attendance and achievement may decrease when

transitioning to remote instruction, with low-income areas being particularly affected.23

Indeed, publicly accessible data from 1,500 schools in New York, New York, indicated that

schools with high Black and Hispanic populations were much more likely to report poor

attendance during remote instruction. 24 On the other hand, the administrative confusion

associated with such an unprecedented transition to remote learning may have resulted in

inaccurate or unreliable reporting, and there was a noticeable drop citywide in absenteeism

during this initial period.

We first attempted to explore this potential bias by including schools enrolled in

CariedAway but not treated because of the onset of COVID-19. Compared with these schools,

treated schools recorded a reduction of approximately 1,500 missed school days, but this effect was

not statistically significant. However, this indicator reflects average attendance throughout all years

of the program, inclusive of years care was not provided in treatment schools. In addition, some

schools received care in multiple years, including years not affected by remote learning policies.

When further restricting the data to exclude attendance records for the 2019 through 2020 school

year, we found that the previously estimated reduction in absences was removed. There remained a

consistent, but nonsignificant, reduction in overall absences when comparing treated with untreated

schools.

CariedAway prioritized schools with predominantly low-income, minority student pop-

ulations, and our findings could suggest a potential positive pathway to improved attendance via

those students who are chronically absent. In contrast to accumulated absences, data reporting

for the proportion of students who were chronically absent may be more robust to the effects of

remote instruction, particularly as this transition occurred in the last quarter of the academic

year. Although treatment onset did not have an immediate impact on this outcome (for

example, reductions in the same year in which treatment was provided), there was a significant

interaction for subsequent years. Overall, treated schools exhibited a nonsignificant reduction in

chronic absenteeism compared with untreated ones. As before, the reduction in the chronically

absent population in treated schools was not significant when removing the 2019 through 2020

school year. The 2022 New York mayor’s management report documented a rise in citywide

chronic absenteeism, citing continued disruptions due to COVID-19 variants and a retrans-

ition to in-person instruction.25

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the potential bias related to COVID-19 and the corresponding shift to remote educational

instruction, our findings suggest that school-based dental programs may have a positive effect on

attendance and chronic absenteeism. The clinical, socioemotional, and educational results of

CariedAway underline the promise of alternative approaches to school-based oral health care, but

also highlight the existing barriers and challenges to sustainable program design. For example,

opacity in legislation, Medicaid policies, and state boards of dental examiners regarding financial

compensation and licensing for clinical personnel directly affects the sustainability of school-based

care. Alternative payment systems for school oral health care, including private practice models,

federally qualified health center models, and dental support organizations may be options for a

sustainable program. As well, engagement with policy stakeholders, school administrators and staff

members, and the local dental community can ensure proper communication of the promise of

school-based oral health care. This structural support can in turn lead to greater sustainability of oral

health care services in schools. n

758 JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023

Dr. Ruff is an associate professor, Department of Epidemiology and Health Dr. Niederman is a professor, Department of Epidemiology and Health

Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, and an associated Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

professor, New York University College of Global Public Health, New York, Disclosures. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

NY. Address correspondence to Dr. Ruff, New York University College of

Dentistry, 380 Second Ave, Room 3-09, New York, NY 10010, email ryan. Research reported in this article was funded by PCS-1609-36824 from the

ruff@nyu.edu. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award. The content is solely

Mr. Habib is a dental student, New York University College of Dentistry, the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official

New York, NY. views of the funding organization, New York University, or the New York

Dr. Godín is a research scientist, Department of Epidemiology and Health University College of Dentistry.

Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

1. GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; Bernabe E, 10. Gooch BF, Griffin SO, Gray SK, et al. Centers for 18. Ruff RR, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride

Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, et al. Global, regional, and Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing dental caries versus therapeutic sealants for the arrest and prevention of

national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from through school-based sealant programs: updated recom- dental caries in low-income minority children: study

1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of mendations and reviews of evidence. JADA. 2009; protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials.

Disease 2017 Study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362-373. 140(11):1356-1365. 2018;19(1):523.

2. Jackson SL, Vann WF Jr., Kotch JB, Pahel BT, 11. Ruff RR, Barry-Godín T, Niederman R. Effect of 19. Naavaal S, Kelekar U. School hours lost due to

Lee JY. Impact of poor oral health on children’s school silver diamine fluoride on caries arrest and prevention: the acute/unplanned dental care. Health Behav Policy Rev.

attendance and performance. Am J Public Health. 2011; CariedAway school-based randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;5(2):66-73.

101(10):1900-1906. Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255458. 20. Starr JR, Ruff RR, Palmisano J, Goodson JM,

3. Mathur VP, Dhillon JK. Dental caries: a disease 12. Ruff RR, Barry-Godín TJ, Niederman R. Medical Bukhari OM, Niederman R. Longitudinal caries preva-

which needs attention. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85(3):202- nurses may be effective in using silver diamine fluoride to lence in a comprehensive, multicomponent, school-based

206. prevent caries compared to dental hygienists in a school- prevention program. JADA. 2021;152(3):224-233.e11.

4. Ruff RR, Senthi S, Susser SR, Tsutsui A. Oral based oral health program. medRxiv. March 22, 2023. 21. Walker SC, Kerns SEU, Lyon AR, Bruns EJ,

health, academic performance, and school absenteeism in Preprint, Version 3, active. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022. Cosgrove TJ. Impact of school-based health center use on

children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta- 05.09.22274845 academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):251-

analysis. JADA. 2019;150(2):111-121.e4. 13. Knopf JA, Finnie RKC, Peng Y, et al. Community 257.

5. Wehby GL. Oral health and academic achievement Preventive Services Task Force. School-based health 22. Van Cura M. The relationship between school-based

of children in low-income families. J Dent Res. 2022; centers to advance health equity: a community guide health centers, rates of early dismissal from school, and

101(11):1314-1320. systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(1):114-126. loss of seat time. J Sch Health. 2010;80(8):371-377.

6. Treadwell HM. The nation’s oral health inequities: 14. Arenson M, Hudson PJ, Lee NH, Lai B. The evi- 23. Dorn E, Hancock B, Sarakatsannis J, Viruleg E.

who cares. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(suppl 1):S5. dence on school-based health centers: a review. Glob COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: the

7. Griffin SO, Wei L, Gooch BF, Weno K, Espinoza L. Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19828745. hurt could last a lifetime. January 1, 2020. McKinsey &

Vital signs: dental sealant use and untreated tooth decay 15. Gift HC, Reisine ST, Larach DC. The social impact Company. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.

among U.S. school-aged children. MMWR Morb Mortal of dental problems and visits. Am J Public Health. 1992; com/industries/education/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-

Wkly Rep. 2016;65(41):1141-1145. 82(12):1663-1668. learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

8. Dye BA, Li X, Thorton-Evans G. Oral health dis- 16. Ruff RR, Barry Godín TJ, Small TM, Niederman R. 24. Schools with high Black and Hispanic populations had

parities as determined by selected Healthy People 2020 Silver diamine fluoride, atraumatic restorations, and oral low student engagement during pandemic, city data shows.

oral health objectives for the United States, 2009-2010. health-related quality of life in children aged 5-13 years: New York City Council. October 15, 2020. Accessed June 9,

NCHS Data Brief. 2012;104:1-8. results from the CariedAway school-based cluster ran- 2023. https://council.nyc.gov/press/2020/10/15/2028

9. Murrin S. Most children with Medicaid in four states domized trial. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):125. 25. Foo J, Gjoni A, Goldstein M, et al. Mayor’s man-

are not receiving required dental services. Murrin S; 17. Piovesan C, Antunes JLF, Mendes FM, Guedes RS, agement report. September 2022. New York: Mayor’s

Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Ardenghi TM. Influence of children’s oral health-related Office of Operations. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://www.

Inspector General. OEI-02-14-00490. Accessed May 27, quality of life on school performance and school absen- nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/mmr2022/2022_

2023. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-14-00490.pdf teeism. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72(2):156-163. mmr.pdf

JADA 154(8) n http://jada.ada.org n August 2023 759

You might also like

- Nutrition Test ReviewDocument14 pagesNutrition Test ReviewDaniel Laoaten100% (2)

- HESI Evolve MED Surg Mini Questions-SmallDocument3 pagesHESI Evolve MED Surg Mini Questions-SmallVictor Ray Welker67% (12)

- Transfusion UpdateDocument342 pagesTransfusion UpdateAdrian Puscas100% (2)

- ASRS Interpretive Report Parent 2 5 Years SAMPLEDocument9 pagesASRS Interpretive Report Parent 2 5 Years SAMPLERafael MartinsNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: School-Based Dental Sealant Programs Prevent Cavities and Are Cost-EffectiveDocument14 pagesHHS Public Access: School-Based Dental Sealant Programs Prevent Cavities and Are Cost-EffectiveDina Auliya AmlyNo ratings yet

- Comm Dent Oral Epid - 2017 - SteinDocument8 pagesComm Dent Oral Epid - 2017 - SteinSherienNo ratings yet

- MainDocument7 pagesMainvaleria bolañosNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Factors Related To Dental CariesDocument9 pagesPrevalence and Factors Related To Dental CariesAamir BugtiNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 540Document8 pages2018 Article 540DINDA PUTRI SAVIRANo ratings yet

- Admin Oamjms2019 869vDocument4 pagesAdmin Oamjms2019 869vangelwhisper88No ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene ProjectDocument8 pagesOral Hygiene Projecttanvirahmed0% (1)

- IJANS - Need of Introducing Oral Health Curriculum in Saudi Schools For Effective Oral Health Promotion and Prevention-A Cross Sectional SurveyDocument2 pagesIJANS - Need of Introducing Oral Health Curriculum in Saudi Schools For Effective Oral Health Promotion and Prevention-A Cross Sectional Surveyiaset123No ratings yet

- Impact Evaluation of A School-Based Oral Health Program Kuwait National ProgramDocument9 pagesImpact Evaluation of A School-Based Oral Health Program Kuwait National ProgramLeo AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Future Dental Journal: E.A. Abdallah, N.E. Metwalli, A.S. BadranDocument7 pagesFuture Dental Journal: E.A. Abdallah, N.E. Metwalli, A.S. BadranNoviyana Idrus DgmapatoNo ratings yet

- Ijd2021 4383418Document6 pagesIjd2021 4383418Javier Cabanillas ArteagaNo ratings yet

- Foreign LiteratureDocument13 pagesForeign LiteratureJm. n BelNo ratings yet

- Increasing Access To Dental Care For Medicaid Preschool Children The Access To Baby and Child Dentistry (ABCD) ProgramDocument12 pagesIncreasing Access To Dental Care For Medicaid Preschool Children The Access To Baby and Child Dentistry (ABCD) ProgramStephanyNo ratings yet

- Library Dissertation On Early Childhood CariesDocument4 pagesLibrary Dissertation On Early Childhood CariesPayToWritePaperBaltimore100% (1)

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocument8 pagesOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizNo ratings yet

- AAPD Policy on Workforce Issues and Delivery of Oral Health Care Services in a Dental HomeDocument5 pagesAAPD Policy on Workforce Issues and Delivery of Oral Health Care Services in a Dental HomefaizahNo ratings yet

- P DentalhomeDocument5 pagesP Dentalhomemehta15drishaNo ratings yet

- Effective Interventions To Prevent Dental Caries in Preschool ChildrenDocument56 pagesEffective Interventions To Prevent Dental Caries in Preschool ChildrenDiego AzaedoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Covid-19 On Dental Education in The United States: Parvati Iyer BDS, Dds Kalid Aziz DDS, Ms David M. Ojcius PHDDocument5 pagesImpact of Covid-19 On Dental Education in The United States: Parvati Iyer BDS, Dds Kalid Aziz DDS, Ms David M. Ojcius PHDFirda IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Dakhili Vol210 PDFDocument10 pagesDakhili Vol210 PDFayuna tresnaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Dental Education - 2020 - Vazquez Alcaraz - Development and Validation of An Instrument To Assess Adherence ToDocument10 pagesJournal of Dental Education - 2020 - Vazquez Alcaraz - Development and Validation of An Instrument To Assess Adherence ToIgnasNo ratings yet

- J Public Health Dent - 2020 - Alrashdi - Education Intervention With Respect To The Oral Health Knowledge Attitude andDocument10 pagesJ Public Health Dent - 2020 - Alrashdi - Education Intervention With Respect To The Oral Health Knowledge Attitude andGauri AtwalNo ratings yet

- School-Based Oral Health Promotion and Prevention ProgramDocument30 pagesSchool-Based Oral Health Promotion and Prevention ProgramAshraf Ali Smadi100% (6)

- Dental status of South African children receiving school oral health servicesDocument7 pagesDental status of South African children receiving school oral health servicesTy WrNo ratings yet

- Scheerman 2019Document11 pagesScheerman 2019Nita Sofia RakhmawatiNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of parental toothbrushing training and fluoride varnish on early childhood cariesDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of parental toothbrushing training and fluoride varnish on early childhood cariesmutiara hapkaNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Practices and Dental Caries Prevalence Among 12 & 15 Years School Children in Ambala, Haryana - A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument6 pagesOral Hygiene Practices and Dental Caries Prevalence Among 12 & 15 Years School Children in Ambala, Haryana - A Cross-Sectional StudyUmar FarouqNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 14 01204Document13 pagesIjerph 14 01204Kim MateoNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument8 pagesResearch ArticleDennis MejiaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 00789 v4Document24 pagesIjerph 18 00789 v4Katia BarreraNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practices On Oral Health of Public School Children of Batangas CityDocument10 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practices On Oral Health of Public School Children of Batangas CityAsia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary ResearchNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of an oral health curriculum in reducing dental caries increment and improving oral hygiene behaviour among schoolchildren of Ernakulam district in Kerala, India: study protocol for a cluster randomised trialDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of an oral health curriculum in reducing dental caries increment and improving oral hygiene behaviour among schoolchildren of Ernakulam district in Kerala, India: study protocol for a cluster randomised trialHindol DasNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Dentistry A Guide For General Practitioner: February 2012Document19 pagesPediatric Dentistry A Guide For General Practitioner: February 2012Basma AminNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries Risk Factors Among Saudi BoysDocument11 pagesDental Caries Risk Factors Among Saudi BoysTania Louise Pioquinto AbuanNo ratings yet

- School Dental Health Programme Pedo 2Document25 pagesSchool Dental Health Programme Pedo 2misdduaaNo ratings yet

- Fit For SchoolDocument17 pagesFit For SchoolIka swastikaNo ratings yet

- Wiener 2021Document8 pagesWiener 2021Bảo Nguyễn TrầnNo ratings yet

- Community Dental HealthDocument16 pagesCommunity Dental HealthsriharidinoNo ratings yet

- Adj 12749Document10 pagesAdj 12749Irfan HussainNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of oral health education programs: A systematic reviewDocument13 pagesEffectiveness of oral health education programs: A systematic reviewceceu nahhNo ratings yet

- BBP PeriodicityDocument13 pagesBBP PeriodicityBeatrice MiricaNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Practices and Oral Health Knowledge Among Students in Split, CroatiaDocument13 pagesOral Hygiene Practices and Oral Health Knowledge Among Students in Split, CroatiaAamirNo ratings yet

- Attitude and Practices of Oral Health Care Behaviour and Eating Habits in Children During Covid-19 PandemicDocument4 pagesAttitude and Practices of Oral Health Care Behaviour and Eating Habits in Children During Covid-19 PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Severity of Gingivitis in School Students Aged 6-11 Years in Tafelah Governorate, South Jordan: Results of The Survey Executed by National Woman's Health Care CenterDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Severity of Gingivitis in School Students Aged 6-11 Years in Tafelah Governorate, South Jordan: Results of The Survey Executed by National Woman's Health Care CenterPutu WidiastriNo ratings yet

- Long Term Effectiveness of The Midwifery Initiated Oral Health Dental Service Program On Maternal Oral Health Knowledge Preventative DentalDocument13 pagesLong Term Effectiveness of The Midwifery Initiated Oral Health Dental Service Program On Maternal Oral Health Knowledge Preventative DentalGita PratamaNo ratings yet

- 6 - Original Article PDFDocument7 pages6 - Original Article PDFIna BogdanNo ratings yet

- Trends in Paediatric First Dental Visit A RetrospeDocument6 pagesTrends in Paediatric First Dental Visit A RetrospeData VaksinNo ratings yet

- Int J Paed Dentistry - 2021 - Khalid - Prevalence of Dental Neglect and Associated Risk Factors in Children and AdolescentsDocument11 pagesInt J Paed Dentistry - 2021 - Khalid - Prevalence of Dental Neglect and Associated Risk Factors in Children and Adolescentsfaridoon7766No ratings yet

- Fit For School' - A School-Based Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programme To Improve Child Health: Results From A Longitudinal Study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDRDocument15 pagesFit For School' - A School-Based Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programme To Improve Child Health: Results From A Longitudinal Study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDRNadila SafiraNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Education Improved Oral Health KnowledgeDocument11 pagesOral Health Education Improved Oral Health KnowledgeGita PratamaNo ratings yet

- Latest Guideline on Caries-risk Assessment and ManagementDocument8 pagesLatest Guideline on Caries-risk Assessment and ManagementPriscila Belén Chuhuaicura SotoNo ratings yet

- Articulo Variables 1Document10 pagesArticulo Variables 1Diego LemurNo ratings yet

- G PerinatalOralHealthCare1Document5 pagesG PerinatalOralHealthCare1perla edith bravoNo ratings yet

- AAPD Guideline on Periodicity of Oral Exams for ChildrenDocument8 pagesAAPD Guideline on Periodicity of Oral Exams for ChildrenTry SidabutarNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics & TherapeuticsDocument7 pagesPediatrics & TherapeuticsAmit PasiNo ratings yet

- G InfantoralhealthcareDocument5 pagesG InfantoralhealthcareMiranda PCNo ratings yet

- LibyaDocument12 pagesLibyaBarsha JoshiNo ratings yet

- AssociationDocument10 pagesAssociationCarlos Alberto CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Healthcare 10 00406Document12 pagesHealthcare 10 00406AamirNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Restorative DentistryFrom EverandPediatric Restorative DentistrySoraya Coelho LealNo ratings yet

- Bernicotal JOP2012Document48 pagesBernicotal JOP2012olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Mapping Indigenous Governance Practices in the PhilippinesDocument205 pagesMapping Indigenous Governance Practices in the PhilippinesReuben Jr UmallaNo ratings yet

- Texting and Relationship: Examining Discourse Strategies in Negotiating and Sustaining Relationships Using Mobile PhoneDocument24 pagesTexting and Relationship: Examining Discourse Strategies in Negotiating and Sustaining Relationships Using Mobile Phoneolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- HG G11 Module 2 RTP PDFDocument10 pagesHG G11 Module 2 RTP PDFARIS BANTOCNo ratings yet

- Simplified Weekly Learning Plan (RAWS)Document12 pagesSimplified Weekly Learning Plan (RAWS)olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Heads and Modifiers: Understanding Grammatical RelationshipsDocument13 pagesHeads and Modifiers: Understanding Grammatical Relationshipsolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Raws WLP - Week2Document4 pagesRaws WLP - Week2olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- g10 Week 1 Quarter 1Document2 pagesg10 Week 1 Quarter 1olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Can Teachers' Age and Experience Influence Teacher Effectiveness in HOTS?Document15 pagesCan Teachers' Age and Experience Influence Teacher Effectiveness in HOTS?olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Raws WLP - Week1Document6 pagesRaws WLP - Week1olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Bernardo2004 2Document16 pagesBernardo2004 2olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Intro To StatsDocument43 pagesIntro To StatsaziclubNo ratings yet

- AntiCheating Answer SheetDocument10 pagesAntiCheating Answer Sheetolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Raws WLP - Week1Document6 pagesRaws WLP - Week1olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- EJ1112529Document11 pagesEJ1112529olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- WCECS2015IAENGDocument6 pagesWCECS2015IAENGolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- 1 Introduction. Language Moocs: An Emerging Field: Elena Bárcena, Elena Martín-MonjeDocument15 pages1 Introduction. Language Moocs: An Emerging Field: Elena Bárcena, Elena Martín-Monjeolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Ra8485 As Amended by Ra10631Document2 pagesRa8485 As Amended by Ra10631Karen Patricio LusticaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Canine Club, Inc.: Rules Applying To Dog ShowDocument26 pagesPhilippine Canine Club, Inc.: Rules Applying To Dog Showolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- DogsDocument1 pageDogsolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Attachment 1 6Document11 pagesAttachment 1 6olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Area And/or Course Horticulture: Rigor/Relevance Framework 6 5 4 3 2 1 C DDocument8 pagesLesson Plan Area And/or Course Horticulture: Rigor/Relevance Framework 6 5 4 3 2 1 C DSaada SayaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Canine Club, Inc.: Rules Applying To Dog ShowDocument26 pagesPhilippine Canine Club, Inc.: Rules Applying To Dog Showolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Phillip J Vet Anim Sci 2014, 40 (1) : 1-12 1: OrvilleDocument12 pagesPhillip J Vet Anim Sci 2014, 40 (1) : 1-12 1: Orvilleolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- CapsletDocument3 pagesCapsletolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Attachment 1 8Document2 pagesAttachment 1 8olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument5 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Logolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- 21 07 11 Headline ActivityDocument2 pages21 07 11 Headline ActivityJohna Mae Dolar EtangNo ratings yet

- Attachment 1 4Document10 pagesAttachment 1 4olga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Psychological Intervention Depression Levels One Sample T-TestDocument3 pagesPsychological Intervention Depression Levels One Sample T-Testolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Finn 2017 TAA Yesterday Today FutureDocument8 pagesFinn 2017 TAA Yesterday Today FutureLinh TranNo ratings yet

- Teva AR 2017 - PharmaceuticalIndustriesLtdDocument805 pagesTeva AR 2017 - PharmaceuticalIndustriesLtdBhushanNo ratings yet

- Low Back Pain in Elderly AgeingDocument29 pagesLow Back Pain in Elderly AgeingJane ChaterineNo ratings yet

- Pecinan 2016Document6 pagesPecinan 2016Faisar Dhamar KusumaNo ratings yet

- Blunt Trauma: Vic V. Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryDocument87 pagesBlunt Trauma: Vic V. Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryGersonito SobreiraNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Injuries ExplainedDocument4 pagesMusculoskeletal Injuries ExplainedJoniele Angelo AninNo ratings yet

- A. Choose A, B, C, D, or E For The Correct Answer!: This Text Is For Questions No 3-5Document8 pagesA. Choose A, B, C, D, or E For The Correct Answer!: This Text Is For Questions No 3-5Muna ShufiyaNo ratings yet

- eFHSIS MANOPSDocument79 pageseFHSIS MANOPSTracy Thompson100% (3)

- Pharmaceutical Biotechnology PDFDocument24 pagesPharmaceutical Biotechnology PDFShyamlaNo ratings yet

- Ligasure Retractable Hook Information SheetDocument2 pagesLigasure Retractable Hook Information SheetCristina PerjuNo ratings yet

- Ethical Concerns in Genetic Engineering c4Document115 pagesEthical Concerns in Genetic Engineering c4api-3803991No ratings yet

- Bilirubin Calibrator PDFDocument2 pagesBilirubin Calibrator PDFInsan KamilNo ratings yet

- Don't Worry, Be HealthyDocument222 pagesDon't Worry, Be HealthyJocelyn PierceNo ratings yet

- Nasal Spray (1222)Document11 pagesNasal Spray (1222)Kapital SenturiNo ratings yet

- 3-Day Food Record AssignmentDocument8 pages3-Day Food Record AssignmentShafiq CharaniaNo ratings yet

- Implantable PacemakerDocument33 pagesImplantable PacemakerShifa Fauzia AfrianneNo ratings yet

- Gram-Positive & Gram-Negative Cocci: Unit 3: Neisseriaceae and Moraxella CatarrhalisDocument18 pagesGram-Positive & Gram-Negative Cocci: Unit 3: Neisseriaceae and Moraxella CatarrhalisKathleen RodasNo ratings yet

- Crohn's Disease Case Study: Matt SimsDocument14 pagesCrohn's Disease Case Study: Matt SimsKipchirchir AbednegoNo ratings yet

- Cancer Immune TherapyDocument452 pagesCancer Immune TherapyatyNo ratings yet

- Definitions: The Social Determinants of Health. SummaryDocument4 pagesDefinitions: The Social Determinants of Health. SummaryS VaibhavNo ratings yet

- Rh-Pregnancy 202240 184928Document2 pagesRh-Pregnancy 202240 184928siddharthNo ratings yet

- Cell Structure and FunctionDocument31 pagesCell Structure and FunctionYoussef samehNo ratings yet

- Best Thing Joey Lott PreviewDocument23 pagesBest Thing Joey Lott Previewhanako1192No ratings yet

- Student HandoutDocument83 pagesStudent HandoutJoise P, Pharm DNo ratings yet

- Capsicum ProductionDocument76 pagesCapsicum Productionexan14431No ratings yet

- Introduction to PEMF Therapy: Regenerating Cells for HealingDocument3 pagesIntroduction to PEMF Therapy: Regenerating Cells for HealingDilip TaylorNo ratings yet