Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1992-7 Physical and Spiritual Fathers

Uploaded by

richmond0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views8 pagesOriginal Title

1992-7_PHYSICAL_AND_SPIRITUAL_FATHERS

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views8 pages1992-7 Physical and Spiritual Fathers

Uploaded by

richmondCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

PHYSICAL AND SPIRITUAL FATHERS *

Archbishop Stylianos (Harkianakis)

The general theme of our National Conference this year is "The

Fathers of the Church and Us". The reason we chose this theme as the

subject of our conference problematics is not only the sacredness of

the Fathers of the Church as such, whose writings are, we would say,

the classics of Christianity, but primarily the general confusion and in-

security created today on account of the daily questioning of all estab-

lished values.

When traditionally established values are questioned, it is natural

for one to be disoriented and for the future of the world to lie at risk.

And when orientation in life is lost, it follows that anxiety will prevail

in all facets of life. This crisis of modern time is surely supported and

aggravated by the formation of contemporary multicultural societies,

the continually expanding internationalism and a way of life that in-

creasingly depends on contemporary technology, which fatally favours

extraversion. Thus derives an unacceptable levelling not only of per-

sons, but also of ideals, since one's noblest desires are forcibly levelled.

It is the very person that sociologists then come, descriptively, to call

"unidimensional".

In any case, such confusion and insecurity, mutually preserved in

a really vicious cycle, are experienced by the particular individual, more

or less consciously, as spiritual division.^ Especially the young people,

born and growing within this new Babylon, experience this problem in

an entirely specific form, namely what we call the "identity crisis". But

what is the meaning of this curious and often misunderstood term? It

simply means that one can no longer know and recognise one's roots,

or be "identified" with them, freely and consciously accepting one's

psycho-spiritual particularity. Yet "roots" and "identity" are almost

equivalent with the notion of "fatherhood". For this reason we could

certainly say that contemporary civilisation is primarily characterised

by a "crisis of fatherhood". As a rule, one who knows that one has

a father, feels secure and has stable foundations in life. The sense of

home and warmth is the first presupposition of peace. Only the person

of nihilistic ideals and the chaotic soul of a Jean-Paul Sartre could

posthumously thank his father, whom he never knew, with the pretext

that "he never met him in life, even for a minute, to obstruct his way"!

The notion of "father", at least in the Judeochristian tradition,

is almost identical with the notion of "authority". When the authority

of the father ensures, and at the same time protects, the truth, then all

holds valid as "authoritative" and genuine, in which case dispute and

insecurity have no place. For this reason it is not by chance that the

prayer, which Christ Himself taught us, begins with the words "Our

Father in heaven", which is not simply a pietistic invocation, but at the

same time, and primarily, a confession that our father is the highest

authority, who is for this precise reason placed in heaven.

After the above, taking the notion of the father as a source and mea-

sure of truth, we should not be accused of "anti-feminism" or "sexism".

* Address delivered at the Fifth National Youth Conference of the Greek Orthodox Arch-

diocese, Adelaide, 29th September - 2nd October, 1991.

PHRONEMA, 7, 1992

6 PHRONEMA

It is obvious that a father is not understood without a mother. This is

why the ancient Cretans could easily and comfortably call the "Father-

land" also "Motherland". What should therefore be strongly stressed

here is the "parental" priority and authority in our life, regardless of

whether we examine it in the form of the father or the mother, which

form is adopted depending on whether we speak within the historico-

social framework of "patriarchy" or of "matriarchy".

Consequently, we may examine the theme of fatherhood from the

following two fundamental viewpoints:

(i) Fatherhood as causal relationship of existence, on the one hand,

and as a factor of the formation of phsysiognomy, on the other.

(ii) Physical and spiritual fatherhood, as antithetical as well as

naturally complementary notions.

From these two perspectives, we are called to search in an elemen-

tary way the profound mystery of fatherhood, at whose inscrutable na-

ture Christ apparently wanted to hint when he said, what at first sight

appeared as hard and unintelligible: "And do not call any one father

on earth, for one is your father, in heaven" (Matt. 23:9).

Precisely from this last remark we are directly led to a third rela-

tionship and viewpoint, from which we must see our theme. Thus we

shall add a third section, (iii), that will examine "spiritual fatherhood

and priesthood". In this way, our theme is not simply complemented,

but rather wholly completed organically in its structural climax. Let us

examine, therefore, in order all the relationships and correlations of the

question already presented.

(i) Fatherhood as causal relationship of existence, on the one hand, and

as a factor for the formation of physiognomy, on the other.

The father, in our elementary self-conscience, is not only our

starting-point, but at the same time the boundary and our limit. As

father he not only symbolises and witnesses absolutely to our limited

nature but also pre-judges, to a certain degree, our future development

and perfection. Thus we could perhaps say that the father is the cons-

tant point in which, almost antiphatically, a centripetal and a centrifu-

gal power meet simultaneously.

As the causal relationship of our existence, the father both binds

and defines us in an entirely decisive manner. Of course this happens

not primarily from his own initiative, but from a pre-established order

in nature, which the faithful cannot but accept as the gift of divine provi-

dence. In this way it is obvious that the father a priori sets us in our

physiological measures, so that for reasonable people there may be no

margin for boasting and insolence throughout life. On the contrary, look-

ing continually at the fact that natural life started from the concrete

and immediate data of another person - the father - people feel primar-

ily a sense of humility. But this humility has no relationship at all with

any feeling of inferiority or shame. One would say that it is a deep,

almost nostalgic, attraction to the pristine clay of our existence, which

secures, on the one hand, the indispensable stability and certainty, so

that we may co-exist with the other creatures in one natural solidarity,

Physical and Spiritual Fathers 1

and, on the other hand, it dictates to us modesty and mutual friend-

ship, so that we may not exceed, in conceit, our measures and become

isolated in an "ivory tower". This very vital, and not at all theoretical,

relationship with the original clay of our natural existence has been won-

derfully preserved by the English term of Latin origin "humility", which,

as we know, etymologically comes directly from "humus" (earth).

Thus, while the father as our natural starting-point could superfi-

cially be regarded as limit and binding, that supposedly limits the bound-

aries of our free activity and growth, in essence it proves to be the radi-

cal and virginal principle, and at the same time the enrichment, of our

person, for which every reasonable and honest person should also feel

- parallel to what was said above - a deep sense of gratitude. Humility,

therefore, and gratitude are the two principal feelings that directly der-

ive from our basic relationship with the father as the starting-point of

our natural existence. It is precisely for this reason that both these feel-

ings play an extremely decisive role in the undisturbed course of our

formation as human persons. In any case, we will not have suspected

the depth and the extent of these two fundamental feelings, of humility

and of gratitude, unless we take into account all that we owe to the father,

not only directly, but also indirectly.

In addition to the direct elements which we receive as children, ini-

tially let us say without any cost or pain, with the act of birth - which

at some time may cost even the life of the mother - we must surely also

add all the benefits which the family environment secures for us abso-

lutely conscientiously and which involve various forms of self-sacrifice

by our parents. Here we must include the entire spectrum of benefits:

food, nurture, education, social protection and settlement, as well as

the fatherly name, which escorts us throughout life with its own validity.

However, there are also the indirect elements secured for us by the

causal dependence of our existence on the father; these are the traits

which, on the basis of the known genetic laws of Mendel, we inherit

from the personalities of other ancestors through our parents. This

many-sided communication with an undefined and long multitude of

ancestors, whom we have never known, in our relationship with the

father constitutes the source of a very deep antinomy: On the one hand,

it is surely a bond of identity, since it is only through the father that

we acquire all biological and inherent psycho-spiritual elements of our

personality. Yet on the other hand, it is also di factor of otherness, namely

of differentiation from the father, precisely because the bequeathed traits

of other ancestors - which exceed the concrete active data of the father's

personality - are the ones which in the first place differentiate him from

his child. Thus it would not at all be an exaggeration to say that our

relationship with the father and the parent in general is not only a bind-

ing factor of determination but also a factor of altogether indefinite

enrichment and liberation. Now, if to this genetically given relationship

and, at the same time, inequality is also added later the formation of

the moral personality of the child, sometimes defined through the free-

dom of conscience, then we have intimated the dramatic tension that

is created between heredity and freedom.

8 PHRONEMA

Of course only the fact that the father chronologically and biolog-

ically precedes the child, gives the former the possibility of influencing

the latter, not only genetically as the natural cause, but also morally

as the authority, at least during the years when the conscience is deci-

sively being formed, the so-called "formative years". But in the final

analysis, the chromosomes and general presuppositions of our existence

have been given by the parent, whereas the conscientious use of these

presuppositions is our own responsibility.

In any case, this antinomical moral duality, with which the already

mature person is at some moment faced - which, for lack of caution,

may surely lead to a degree of division of personality, if not also of

schizophrenia - is balanced rather with success if one considers the fol-

lowing significant distinction.

While, on the one hand, the direct and active will, which we ex-

press in any of our concrete moral decisions, certainly constitutes our

personal voice, and therefore our primary responsibility, on the other

hand, the kind of somewhat undefined anxiety and doubt, which we

have at the same time deeply in our conscience, betrays that within us

are included an entire world of forgotten ancestors, who also seek to

be justified. And since elementary justice demands that the opinion of

the many prevail over the one, the moral command has been so con-

cisely formulated, that one2 ought to be "master of one's will and ser-

vant of one's conscience".

All the above, which we have tried to expound, admittedly some-

what schematically in reference to the causal, on the one hand, and the

moral, on the other, relationship between father and child, constitute

sufficient reasons to render conscious the need to know the father as

closely as possible; which leads, as is natural, directly to a deeper and

fuller knowledge of ourselves.

(ii) Physical and spiritual fatherhood, as antithetical but also mutually

complementary notions

The saying ascribed to Alexander the Great, namely that one owes

"life to one's parents, but good life to one's teachers", seems to set -

though somewhat simplistically at first sight - the line of demarcation

between physical and spiritual fatherhood. First of all, we must recall

that already in ancient times, and especially in the East, the relation-

ship between teacher and student was considered almost the same as

that between father and child, which is also affirmed by the above com-

parison of Alexander the Great. Furthermore we must say that these

words of the Macedonian Commander appear at first sight truly sim-

plistic, for upon careful observation things are not always so simple or

clearly distinct. From experience we know that it is almost impossible

to find a father who bequeathed to his child only the good of physical

existence, without at the same time teaching with word - and even

perhaps more so and more frequently with his silent example through-

out life - some fundamental values and truths of life. It seems equally

impossible that there was a teacher worthy of the name, who would not

have cared at some time for his student, with the interest and affection

Physical and Spiritual Fathers 9

of the physical father. Yet the distinction between physical and spiritual

fatherhood is also conceptually legitimate, and historically founded.

Even in the case where the physical father would by profession be the

greatest spiritual man, he would never be able to play the role of a

stranger, equal or sometimes inferior, for his physical children. So,

reasonably, a first fundamental question is raised: to what is this curi-

ous phenomenon due, that undoubtedly constitutes a blatant injustice?

One is led to believe that no matter how far we analyse this phenome-

non psychologically, only two explanations are probable.

First explanation: that the absolute "familiarisation" created by

the family environment with the many daily simple needs or even insig-

nificances - not to mention frictions, bitterness and disappointments

- inevitably demythologise the ideal character and dissolve the magic

with which the notion of teacher and spiritual father is expressed also

by the proverbial and somewhat humourous remark, that "Even

Napoleon the Great was not Great for his valet"! And we say that this

truth is unfortunately great, because properly and rightly the family daily

needs, in which the person is inevitably involved, should render still more

wonderful and sacred the grandeur of the spiritual person, who is will-

ingly humbled out of love and a sense of duty. Yet such assessment and

appreciation of data can only be made by particularly sensitive natures

and is not unfortunately acceptable to the average person.

The second explanation must be regarded as much more persua-

sive. It concerns the significance of the! factor of free choice. It consti-

tutes an even greater honour for one's dignity to select freely a stranger

as one's teacher and spiritual guide, than to accept slavishly the imposed

physical father from the blind need of biological dependence "at home",

without even being asked. Now the choice, we must say, does not at

all lose anything of its value as an act of freedom, unless it should hap-

pen to be done, not only by the person interested, but also by the par-

ents or trustees. We are talking about the famous "Elective Affinities"

(Wahlverwandtschaften) of Goethe's novel, so named.

Whatever other reasons one might imagine, when analysing the

phenomenon which we have tried to explain, the undisputed fact re-

mains that physical and spiritual fatherhood do not coincide. Perhaps

we must now say that not only do they not coincide, but are also clearly

distinguished as antithetical notions, without meaning by this that they

are not mutually complementary. An elementary comparison of parallel

elements and characteristics in both cases will better clarify the distinc-

tion in question. Let us see some of the elements that come to mind

in relation to this comparison:

(a) The factor of breadth: While the physical father is in reality

limited to have only a small number of children, the spiritual father

is free to have an infinite number of spiritual children.

(b) The factor of distance: While the physical father is obliged to

participate with his whole psychosomatic being - and therefore in the

most direct and intimate way - in the birth of his physical children, the

spiritual father gives birth by word alone, or also by silence, even from

unlimited distances.

(c) The factor of destruction and death: For the physical father it

10 PHRONEMA

is inevitable, with the passage of time, that the possibilities of giving

birth to new children are reduced, until death finally sets an end to fer-

tility. For the spiritual father, on the contrary, these limitations and bi-

ological fetters of nature do not exist. While alive, he gives birth un-

sparingly, and when dead he continues to give birth undisturbed by the

depths of the ages and to the end of the world, with his memory or

legend, but especially with his consecrated writings.

(d) The factor of multiplication: The essence of physical father-

hood, namely its benefits, when divided among more children are con-

tinually being reduced and are finally altogether exhausted. In spiritual

fatherhood, precisely the opposite happens. The more the number of

spiritual children participating in the spiritual goods, the more these

goods are multipled in the number of the division.

(e) The factor of bonding: While the authority of the physical father

is mainly based on the physical or legal obligation that the children have

to respect the father, the authority of the spiritual father is based on

free persuasion and inspiring respect, and for this reason it is entirely

of a moral nature. Proof of this is also the freedom, which the spiritual

child permanently preserves, to desert the spiritual father as soon as

the latter ceases to inspire confidence and respect.

(f) The factor of concord and solidarity: The understanding pre-

vails widely that the bonds of blood are stronger than all other bonds

among people, and that, consequently, relatives by blood are more stead-

ily and more deeply united than any other. Yet it must be remarked that

it is the spiritual bonds that mainly endure longer in time and in trials.

For the supports of biology are by definition of a different quality from

those of conscience. In any case, the very word "concord", which is

something deeper than "agreement", shows that the spirits and the con-

sciences must sound together, in order that this rare good may prevail

among people.

By analysing and comparing the two forms of fatherhood, we may

possibly discover other interesting and characteristic differences. Yet,

even the cases expounded above are sufficient to persuade us of at least

two basic points. First, that spiritual fatherhood is certainly of nobler

character; it is for this reason that, although it is related so much - es-

pecially morphologically - with physical fatherhood, yet it is neither iden-

tical nor equal to it. Second, that this difference in character in no way

gives us the right to underrate physical fatherhood. On the contrary,

after the above analysis, it becomes clearer how substantially complimen-

tary they are to each other. Physical fatherhood offers the "primary

source", but also the first basis on which to build spiritual fatherhood.

And again, spiritual fatherhood adorns and consecrates the products

of physical fatherhood. If spiritual fatherhood is entirely powerless and

inconceivable without physical fatherhood, to that extent the latter

without the former also remains incomplete and unfinished as human

formation.

For this reason we ought, with the same attention and devotion,

to honour both forms of fatherhood which finally aim at a common

purpose: to render eternal on the one hand, and to render perfect on

the other, the human person as the highest value in the created world.

Physical and Spritual Fathers 11

(iii) Spiritual Fatherhood and Priesthood

We have said, by way of introduction, above that perhaps Christ

forbade us to call anyone on earth father in order to hint at the inscruta-

ble depth of the mystery of fatherhood. And He hastened at the same

time to give us also the direct reason for this prohibition, namely the

uniqueness of fatherhood, which strictly speaking must be reserved for

the creator God.

Such evaluation of fatherhood, which transcends the created limits

of being within the world and literally refers only to the transcendent

God, is certainly not a mysticist or merely pietistic explanation. On the

contrary, it is a teaching that is perfectly consistent with the most fun-

damental biblical doctrine - the creation ex nihilo of the world - which

could not but find even a remote reflection in the human conscience,

thus leaving its vivid traces in the primitive structures of the early, and

later on of the so-called patriarchal, family.

For this reason, in the earliest family it was entirely natural for the

functions of teacher and priest to coincide in the person of the leader

of the family, the father. This historical fact clearly proves that spiritu-

al fatherhood does not always consummate only in the conventional

or "established" priesthood, but rather and mainly in a more charis-

matic prophetic presence within the world, which as a rule ought of

course to be incarnate in a more persuasive way in the "instituted"

priesthood of the time. Now if it does not always attain it, it is at least

consoling that it also does not monopolise it.

On the theme of spiritual fatherhood, St Paul seems to be more

categorical. He strictly relates it only to the primitive and authentic evan-

gelisation, which he assumes in the name of the Lord who sends him

out. The authenticity of this evangelism results from the characteristic

sufferings for the sake of the Gospel, as St Paul expounds them in the

First Epistle to the Corinthians (4:9-13). And it is not accidental that

only after this dramatic description does the Apostle Paul, in the direct

sequence of his Epistle, dare to appeal to this unique relationship with

the Corinthians, saying: "I am not ashamed to write these things to

you, but I admonish you as my beloved children. For even if you have

countless guides in Christ, yet you have not many fathers; for I have

given birth to you in Christ Jesus through the gospel" ( 1 Cor. 4:14-16).

With this special dimension in the meaning of spiritual fatherhood,

as St Paul defines it, it becomes clear that in Christianity the term

*'spiritual father" cannot be ascribed to any teacher or guide, but has

a strictly "Christocentric" character. In other words, it is not enough

to teach generally and abstractly "in Christ" or "according to Christ",

but one must also be "in the place of Christ".

It was very natural that spiritual fatherhood be restricted from the

beginning to the person of the incarnate Logos of God, since He alone

is literally "the reflection of the Father's glory" (Heb. 1:3) or, as St Paul

says, "He is the image of the invisible God" (Col. 1:15).

In any case, this exclusiveness of fatherhood served always as the

centre of self-conscience for Christ, that made him expect from the faith-

ful a radical disassociation from any other form of fatherhood: "if any

12 PHRONEMA

one comes to me and does not hate his father, and mother, and wife,

and children, and brothers and sisters, and even his own life, such can-

not be my own disciple" (Luke 14:26).

And one of course may justifiably ask: is it necessary that the Chris-

tian hate his parents and relatives, or even his own life, in order to fol-

low Christ? Is there no other way, more peaceful and more loving, es-

pecially in Christianily, which is regarded as the religion of love par-

excellence? How is such a claim reconciled with what St Paul writes in

his First Epistle to Timothy (5:8): "Now if one does not provide for

his relatives, and especially for his own family, he has disowned the faith

and is worse than an unbeliever". Not only this, but St Paul goes even

further, stating that if he was to help his brothers and relatives in the

flesh, he would be ready even to become "anathema" for their sake

(cf. Rom. 9:3).

After all this, we must say that Christ demands a radical break with

our family environment not generally and vaguely, but only when this

environment comes into opposition with the Gospel, namely when we

have to choose between Christ and our relatives and friends. The Lord

says this clearly: "Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not

worthy of me; and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not

worthy of me" (Matt. 10:37).

In any case, all this "Christian character" taken in Christianity by

the notion of the spiritual father, does not remain loose and vague, but

soon becomes localised and restricted in the institutional Priesthood

of the Church, and particularly in the Bishop, who is found "in the

place and type of Christ".3

In other words, it was considered to be self-evident that the "father"

should only be the one who is sent from above, the Apostle and his

successor Bishop, who with God's word gives birth to new members

within the Church. And by extension, this fatherhood was recognised

also in every other priest and/or monk, since they, too, contribute to

the same sacred task.

NOTES

1 The general climate of confusion and insecurity, of which we speak, has been very

characteristically described by Professor G. Mantzaridis, as follows: "The formation

of many specialised areas, with independent and sometimes self-conflicting orienta-

tions, favours the formation of moral pluralism or even of moral confusion, as that

which we live in our times. If one has no point of support beyond society, it is natural

to be carried away by this confusion and remain without purpose. Thus, apart from

the inner division between will and action, one also faces the external severing of so-

cial life". Cf. Christian Ethics 3rd edn (Thessalonika (in Greek) 1991) p. 26.

2 This moral aphorism belongs to the famous Austrian poet Marie von Ebner-

Eschenbach. Cf. Dimitra Markata, "Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach: Die Aphorismen' '

(Dissertation submitted to the University of Vienna, 1989, p. 117).

3 Archbishop Stylianos of Australia, ' The Bishop in the Church' ', in Voice of Orthodoxy,

May and June 1984.

You might also like

- Humanae VitaeDocument22 pagesHumanae VitaeToniski ToniskiNo ratings yet

- Humanae Vitae Encyclical Provides Church's Teachings on Birth RegulationDocument20 pagesHumanae Vitae Encyclical Provides Church's Teachings on Birth RegulationAnihan Fpti100% (1)

- Nurturing and Bringing Up Children in Traditional Chakhesang Naga SocietyDocument15 pagesNurturing and Bringing Up Children in Traditional Chakhesang Naga SocietyRukuzoNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet 2Document27 pagesPamphlet 2yani_hamhampandaNo ratings yet

- Humanae Vitae: Honored Brothers and Dear Sons, Health and Apostolic BenedictionDocument14 pagesHumanae Vitae: Honored Brothers and Dear Sons, Health and Apostolic BenedictionStMichaelNo ratings yet

- Catholic Diocese Document on Gender & Human PersonDocument8 pagesCatholic Diocese Document on Gender & Human PersonAna P UCAMNo ratings yet

- Human SexualityDocument37 pagesHuman Sexualityrijie wenceslaoNo ratings yet

- Humanae Vitae: On The Regulation of BirthDocument16 pagesHumanae Vitae: On The Regulation of BirthJohn KennedyNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Sexuality (Frithjof Schuon) PDFDocument14 pagesThe Problem of Sexuality (Frithjof Schuon) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- Who Is My NeighborDocument11 pagesWho Is My NeighborCarl KussNo ratings yet

- Cencini BelongingDocument10 pagesCencini BelongingMagno JalesNo ratings yet

- The Pontifical Council For The FamilyDocument37 pagesThe Pontifical Council For The FamilyZantedeschia Fialovy100% (1)

- The Fourth Commandment ExplainedDocument22 pagesThe Fourth Commandment ExplainedRio BoncalesNo ratings yet

- The Sanctity of Family and LifeDocument19 pagesThe Sanctity of Family and LifeCeline Socrates100% (1)

- The Truth of The Encyclical Humanae VitaeDocument8 pagesThe Truth of The Encyclical Humanae VitaeasdasdNo ratings yet

- The Revelation of Righteous Judgment SeriesDocument9 pagesThe Revelation of Righteous Judgment SeriesEnrique RamosNo ratings yet

- secdocument_8681Document67 pagessecdocument_8681debra.glisson665No ratings yet

- Personal Religion in Egypt Before Christianity (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandPersonal Religion in Egypt Before Christianity (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- New Skin For The Old TestamentDocument4 pagesNew Skin For The Old TestamentAran PatinkinNo ratings yet

- Las Tres Conversiones Del Alma, InglesDocument45 pagesLas Tres Conversiones Del Alma, InglesMaria RosaNo ratings yet

- The Origin of the World According to Revelation and ScienceFrom EverandThe Origin of the World According to Revelation and ScienceNo ratings yet

- The Sexual Relationship in Christian Thought (Philip Sherrard) PDFDocument16 pagesThe Sexual Relationship in Christian Thought (Philip Sherrard) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- How Can God Allow Such ThingsDocument34 pagesHow Can God Allow Such ThingsVibhuti Dabrāl100% (1)

- Who Is My Mother... Cópia de Quem É Minha Mãe e ..., 01 06 2010Document9 pagesWho Is My Mother... Cópia de Quem É Minha Mãe e ..., 01 06 2010Fernandes MartinhoNo ratings yet

- Ce ReviewerDocument11 pagesCe ReviewerLecery Sophia WongNo ratings yet

- Draft of The 2017 Strenna: WE ARE FAMILY! Every Home, A School of Life and LoveDocument7 pagesDraft of The 2017 Strenna: WE ARE FAMILY! Every Home, A School of Life and Lovepackman737No ratings yet

- The Virtue of Hope: How Confidence in God Can Lead You to HeavenFrom EverandThe Virtue of Hope: How Confidence in God Can Lead You to HeavenNo ratings yet

- RE4 semisDocument39 pagesRE4 semisWyllow PapangoNo ratings yet

- Rahner - Nature and Grace PDFDocument24 pagesRahner - Nature and Grace PDFDominic LeRouzèsNo ratings yet

- Science: A Way To HeavenDocument9 pagesScience: A Way To HeavenBahngalionNo ratings yet

- Nikolaos Loudovikos__Consubstantiality Beyond Perichoresis. Personal Threeness, Intra-divine Relations, And Personal Consubstantiality in Augustine's, Aquinas' and Maximus the Confessor's Trinitarian TheologiesDocument21 pagesNikolaos Loudovikos__Consubstantiality Beyond Perichoresis. Personal Threeness, Intra-divine Relations, And Personal Consubstantiality in Augustine's, Aquinas' and Maximus the Confessor's Trinitarian TheologiesAni LupascuNo ratings yet

- What If Both Creationists And Atheists Evolutionists Are WrongFrom EverandWhat If Both Creationists And Atheists Evolutionists Are WrongNo ratings yet

- Madigan Phronema Embroidering After Review Typos CorrectedDocument24 pagesMadigan Phronema Embroidering After Review Typos CorrectedDaniel MadiganNo ratings yet

- Christian Married LoveFrom EverandChristian Married LoveRaymond DennehyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Love—Marriage—Birth Control Being a Speech delivered at the Church Congress at Birmingham, October, 1921From EverandLove—Marriage—Birth Control Being a Speech delivered at the Church Congress at Birmingham, October, 1921No ratings yet

- The Esoteric Basis of ChristianityDocument44 pagesThe Esoteric Basis of ChristianityalnevoNo ratings yet

- Peterson-Living Into God's StoryDocument3 pagesPeterson-Living Into God's StoryjoshuasethandersonNo ratings yet

- The Spirit in Nature: A Scientific History of the Universe from a Spiritual PerspectiveFrom EverandThe Spirit in Nature: A Scientific History of the Universe from a Spiritual PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- God as Creator and Sustainer in Human HistoryDocument28 pagesGod as Creator and Sustainer in Human HistoryLucian TomoiagăNo ratings yet

- A Reformed Christian WorldviewDocument16 pagesA Reformed Christian WorldviewJeff PriceNo ratings yet

- T E D M: HE ND OF Ogmatic EtaphysicsDocument4 pagesT E D M: HE ND OF Ogmatic EtaphysicsmiguelostermanNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Theosophy: by Kate HillardDocument9 pagesThe Ethics of Theosophy: by Kate HillardKannanNo ratings yet

- Chap4,5religious ExpDocument37 pagesChap4,5religious Expgloria starbucksNo ratings yet

- Easter ApostlesDocument7 pagesEaster ApostlesrichmondNo ratings yet

- Financial Handbook For Congregations 2017Document198 pagesFinancial Handbook For Congregations 2017richmondNo ratings yet

- Deacon Ministry OrganizationDocument13 pagesDeacon Ministry OrganizationrichmondNo ratings yet

- Finance 2016Document83 pagesFinance 2016richmondNo ratings yet

- Church Growth and The Independent ChristianDocument8 pagesChurch Growth and The Independent ChristianrichmondNo ratings yet

- Gawrisch ChristiansDocument7 pagesGawrisch ChristiansrichmondNo ratings yet

- Church Funds Management - 5Document4 pagesChurch Funds Management - 5richmondNo ratings yet

- Boersma Stephen A1988Document149 pagesBoersma Stephen A1988richmondNo ratings yet

- Church Finance Handbook Corrected 12-17-10Document187 pagesChurch Finance Handbook Corrected 12-17-10richmondNo ratings yet

- Deacon's ManualDocument23 pagesDeacon's ManualrichmondNo ratings yet

- Deacon Questionnaire July 2015Document10 pagesDeacon Questionnaire July 2015richmondNo ratings yet

- Dom Ministry+of+eldersDocument2 pagesDom Ministry+of+eldersrichmondNo ratings yet

- 13 BC 12Document6 pages13 BC 12richmondNo ratings yet

- Christian LibertyDocument32 pagesChristian LibertyrichmondNo ratings yet

- Church Administration Manual 2015Document47 pagesChurch Administration Manual 2015richmondNo ratings yet

- 13 BC 11Document6 pages13 BC 11richmondNo ratings yet

- Alizons Psychic Secrets Psychic Ability Guide PDFDocument20 pagesAlizons Psychic Secrets Psychic Ability Guide PDFSanam1378No ratings yet

- 13 BC 04Document6 pages13 BC 04richmondNo ratings yet

- Appointment and Ordination of EldersDocument6 pagesAppointment and Ordination of EldersrichmondNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Sonship Under Spiritual FathersDocument4 pagesBenefits of Sonship Under Spiritual FathersKusi Baffour Johnney100% (2)

- Angels and Other Heavenly BeingsDocument10 pagesAngels and Other Heavenly BeingsrichmondNo ratings yet

- Notes 230908 100442Document12 pagesNotes 230908 100442richmondNo ratings yet

- 13 BC 06Document6 pages13 BC 06richmondNo ratings yet

- Notes 230905 062844Document2 pagesNotes 230905 062844richmondNo ratings yet

- Indian Superman Power ChantsDocument4 pagesIndian Superman Power ChantsrichmondNo ratings yet

- Laffzlh - 1589236092.tailoringDocument582 pagesLaffzlh - 1589236092.tailoringAdriana Raquel Raquel Lopez Bard100% (2)

- Learning, Perception, Attitudes, Values, and Ethics: Fundamentals of Organizational Behavior 2eDocument21 pagesLearning, Perception, Attitudes, Values, and Ethics: Fundamentals of Organizational Behavior 2eJp AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Judging MR and Ms UNDocument9 pagesCriteria For Judging MR and Ms UNRexon ChanNo ratings yet

- Module IV StaffingDocument3 pagesModule IV Staffingyang_19250% (1)

- 3.part I-Foundations of Ed (III)Document25 pages3.part I-Foundations of Ed (III)Perry Arcilla SerapioNo ratings yet

- Packex IndiaDocument12 pagesPackex IndiaSam DanNo ratings yet

- Marine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFDocument321 pagesMarine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFAlberto MysterioNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 7 FIRST QUARTER EXAMDocument2 pagesENGLISH 7 FIRST QUARTER EXAMAlleli Faith Leyritana100% (1)

- 1868 Sop Work at HeightDocument10 pages1868 Sop Work at HeightAbid AzizNo ratings yet

- Food and Beverages Service: Learning MaterialsDocument24 pagesFood and Beverages Service: Learning MaterialsJoshua CondeNo ratings yet

- CLASS 7B Result Software 2023-24Document266 pagesCLASS 7B Result Software 2023-24JNVG XIB BOYSNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 Ielts Speaking Part 1 Questions Sample Answers IELTS FighterDocument15 pagesUNIT 2 Ielts Speaking Part 1 Questions Sample Answers IELTS FighterVi HoangNo ratings yet

- Not Qualified (Spoken Word Poem) by JonJorgensonDocument3 pagesNot Qualified (Spoken Word Poem) by JonJorgensonKent Bryan Anderson100% (1)

- Student (Mechanical Engineering), JECRC FOUNDATION, Jaipur (2) Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, JECRC FOUNDATION, JaipurDocument7 pagesStudent (Mechanical Engineering), JECRC FOUNDATION, Jaipur (2) Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, JECRC FOUNDATION, JaipurAkash yadavNo ratings yet

- 100 Answers To Common English QuestionsDocument9 pages100 Answers To Common English Questionsflemus_1No ratings yet

- Kim Hoff PAR 117 JDF 1115 Separation AgreementDocument9 pagesKim Hoff PAR 117 JDF 1115 Separation AgreementlegalparaeagleNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance AsiaDocument2 pagesIslamic Finance AsiaAhmad FaresNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas Engines 2019Document428 pagesNatural Gas Engines 2019Паша Шадрёнкин100% (1)

- USA V Brandon Hunt - April 2021 Jury VerdictDocument3 pagesUSA V Brandon Hunt - April 2021 Jury VerdictFile 411No ratings yet

- Use VCDS with PC lacking InternetDocument1 pageUse VCDS with PC lacking Internetvali_nedeleaNo ratings yet

- 7) Set 3 Bi PT3 (Answer) PDFDocument4 pages7) Set 3 Bi PT3 (Answer) PDFTing ShiangNo ratings yet

- National Geographic USA - 01 2019Document145 pagesNational Geographic USA - 01 2019Minh ThuNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Classifications of CommunicationDocument48 pagesLesson 5 Classifications of CommunicationRovenick SinggaNo ratings yet

- Fabric Trademark and Brand Name IndexDocument15 pagesFabric Trademark and Brand Name Indexsukrat20No ratings yet

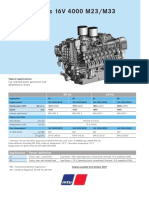

- Diesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZDocument2 pagesDiesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZAlberto100% (1)

- A. Pawnshops 4. B. Pawner 5. C. Pawnee D. Pawn 6. E. Pawn Ticket 7. F. Property G. Stock H. Bulky Pawns 8. I. Service Charge 9. 10Document18 pagesA. Pawnshops 4. B. Pawner 5. C. Pawnee D. Pawn 6. E. Pawn Ticket 7. F. Property G. Stock H. Bulky Pawns 8. I. Service Charge 9. 10Darwin SolanoyNo ratings yet

- Harsheen Kaur BhasinDocument20 pagesHarsheen Kaur Bhasincalvin kleinNo ratings yet

- The Oz DietDocument5 pagesThe Oz Dietkaren_wilkesNo ratings yet

- SALICYLATE POISONING SIGNS AND TREATMENTDocument23 pagesSALICYLATE POISONING SIGNS AND TREATMENTimmortalneoNo ratings yet

- Chimdesa J. Functional FoodsDocument201 pagesChimdesa J. Functional FoodsChimdesa100% (1)

- Development Plan-Part IV, 2022-2023Document3 pagesDevelopment Plan-Part IV, 2022-2023Divina bentayao100% (5)