Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Slow-Productivity Excerpt

Uploaded by

Enrique PueblaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Slow-Productivity Excerpt

Uploaded by

Enrique PueblaCopyright:

Available Formats

IN TROD U C TI ON

I n the summer of 1966, toward the end of his second year as a

staff writer for The New Yorker, John McPhee found himself on

his back on a picnic table under an ash tree in his backyard near

Princeton, New Jersey. “I lay down on it for nearly two weeks, star-

ing up into branches and leaves, fighting fear and panic,” he recalls

in his 2017 book, Draft No. 4. McPhee had already published five

long-form articles for The New Yorker and, before that, had spent

seven years as an associate editor for Time. He wasn’t, in other

words, new to magazine writing, but the article that immobilized

him on his picnic table that summer was the most complicated he

had yet attempted to write.

McPhee had previously written profiles, such as his first major

piece for The New Yorker, “A Sense of Where You Are,” which fol-

lowed the Princeton University basketball star Bill Bradley. He

had also written historical accounts: in the spring of 1966, he pub-

lished a two-part article on oranges that traced the humble fruit’s

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 1 12/5/23 5:09 PM

2 | SLOW PRODUCTIVITY

history all the way back to its first reference in 500 BCE in China.

McPhee’s current project, however, which tackled the impossibly

broad topic of the Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey, was at-

tempting to do much more. Instead of writing a focused profile, he

had to weave the stories of multiple characters, including extensive

re-creation of dialogue and visits to specific settings. Instead of

summarizing the history of a single object, he had to dive into the

geological, ecological, and even political backstory of an entire

region.

McPhee spent eight months researching the topic in the lead-up

to his picnic table paralysis, gathering what he later called “enough

material to fill a silo.” He had traveled from his Princeton home

down to the Pine Barrens more times than he could easily remem-

ber, often bringing a sleeping bag to extend his stay. He had read

all the relevant books and talked to all the relevant people. Now

that he had to start writing, he felt overwhelmed. “To lack confi-

dence at the outset seems rational to me,” he explained. “It doesn’t

matter that something you’ve done before worked out well. Your

last piece is never going to write your next one for you.” So McPhee

lay on his picnic table, looking up at the branches of that ash tree,

trying to figure out how to make this lumbering mass of sources

and stories work together. He stayed on that table for two weeks

before a solution to his quandary finally arrived: Fred Brown.

Early in his research, McPhee had met Brown, a seventy-nine-

year-old who lived in a “shanty” deep in the Pine Barrens. They

had subsequently spent many days wandering the woods together.

The revelation that jolted McPhee off his picnic table was that

Brown seemed to be connected in some way to most of the topics

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 2 12/5/23 5:09 PM

INTRODUCTION | 3

that he wanted to cover in his article. He could introduce Brown

early in the piece, and then structure the topics he wanted to ex-

plore as detours from the through line of his adventures with

Brown.

Even after this moment of insight, it still took McPhee more

than a year to finish writing his article, working in a modest rental

office off Nassau Street in Princeton, located above an optome-

trist’s shop and across the hall from a Swedish massage parlor. The

finished piece would stretch to more than thirty thousand words

and be divided into two parts, to appear in two consecutive issues

of the magazine. It’s a marvel of long-form reporting and one of

the more beloved entries in McPhee’s long bibliography. It couldn’t

have existed, however, without McPhee’s willingness to put every-

thing else on hold, and just lie on his back, gazing upward toward

the sky, thinking hard about how to create something wonderful.

I came across this story of John McPhee’s unhurried approach dur-

ing the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, which was, to put

it mildly, a complicated time for knowledge workers. As that anx-

ious spring unfolded, a long-simmering unease with the demands

of productivity among those who toil in offices and at computer

screens for a living began to boil over under the strain of pandemic-

related disruptions. As someone who often touched on productivity

issues in my writing on technology and distraction, I experienced

this intensifying backlash directly. “Productivity language is an

impediment to me,” one of my readers explained to me in an email.

“The pleasure in thinking and doing things well is such a deep-

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 3 12/5/23 5:09 PM

4 | SLOW PRODUCTIVITY

wired human pleasure . . . and it feels (to me) diluted when it’s

linked to productivity.” A commenter on my blog added, “The

productivity terminology encodes not only getting things done,

but doing them at all costs.” The specific role of the pandemic as

a driver of these sentiments was often evident in this feedback.

As one insightful reader elaborated, “The fact that productivity =

widgets produced is, if anything, clearer during this pandemic as

parents fortunate enough to still have jobs are expected to produce

similar amounts of work while caring for and educating kids.”

This energy surprised me. I love my audience, but fired up is not

usually a term I used to describe them. Until now. Something was

clearly changing.

As I soon discovered, this growing anti-productivity sentiment

wasn’t confined only to my readers. Between the spring of 2020

and the summer of 2021, a period spanning less than a year and a

half, at least four major books were published that took direct aim

at popular notions of productivity. These included Celeste Head-

lee’s Do Nothing, Anne Helen Petersen’s Can’t Even, Devon Price’s

Laziness Does Not Exist, and Oliver Burkeman’s delightfully sar-

donic Four Thousand Weeks. This exhaustion with work was also

reflected in multiple waves of heavily reported social trends that

crested one after another during the pandemic. First there was the

so-called Great Resignation. Though this phenomenon encom-

passed retreats from labor force participation in many different

economic sectors, among these many sub-narratives was a clear

trend among knowledge workers to downgrade the demands of

their careers. The Great Resignation was then followed by the rise

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 4 12/5/23 5:09 PM

INTRODUCTION | 5

of quiet quitting, in which a younger cohort of workers began to

aggressively push back on their employers’ demands for produc-

tivity.

“We are overworked and overstressed, constantly dissatisfied,

and reaching for a bar that keeps rising higher and higher,” writes

Celeste Headlee in the introduction to Do Nothing. A few years

earlier, this sentiment might have seemed provocative. By the time

the pandemic peaked, however, she was preaching to the choir.

As I witnessed this fast-growing discontent, it became clear to me

that something important was happening. Knowledge workers were

exhausted—burned out from an increasingly relentless busyness.

The pandemic didn’t introduce this trend so much as push its worst

excesses beyond the threshold of tolerability. More than a few knowl-

edge workers, thrust suddenly into remote work, their kids scream-

ing in the next room as they suffered through yet another Zoom

meeting, began to wonder, “What are we really doing here?”

I began extensively covering knowledge worker discontent, as

well as alternative constructions of professional meaning, on my

long-standing newsletter, as well as on a new podcast I launched

early in the pandemic. As the anti-productivity movement contin-

ued to pick up speed, I also began to cover the topic more fre-

quently in my reporting for The New Yorker, where I’m on the

contributor staff, ultimately leading, during the fall of 2021, to my

taking on a twice-a-month column called Office Space that was

dedicated to this subject.

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 5 12/5/23 5:09 PM

6 | SLOW PRODUCTIVITY

The storylines I uncovered were complicated. People were over-

whelmed, but the sources of this increasing exhaustion weren’t ob-

vious. Online discussion of these issues offered no shortage of

varied, and sometimes contradictory, theories: Employers were re-

lentlessly increasing the demands on their employees in an attempt

to extract more value from their labor. No, it’s actually an internal-

ized culture valorizing busyness, driven by online productivity in-

fluencers, that’s leading to our exhaustion. Or maybe what we’re

really seeing is the inevitable collapse of “last-stage capitalism.”

Fingers were pointed and frustrations vented; all the while, knowl-

edge workers continued to descend into increasing unhappiness.

The situation seemed dark, but as I continued my own research on

this topic, a glimmer of optimism emerged, sparked by the very tale

with which we opened this discussion.

When I first encountered the story of John McPhee’s long days

looking up at the leaves in his backyard, I received it nostalgically—

a scene from a time long past, when those who made a living with

their minds were actually given the time and space needed to craft

impressive things. “Wouldn’t it be nice to have a job like that where

you didn’t have to worry about being productive?” I thought. But

eventually an insistent realization emerged. McPhee was produc-

tive. If you zoom out from what he was doing on that picnic table

on those specific summer days in 1966 to instead consider his en-

tire career, you’ll find a writer who has, to date, published twenty-

nine books, one of which won a Pulitzer Prize, and two of which

were nominated for National Book Awards. He has also penned

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 6 12/5/23 5:09 PM

INTRODUCTION | 7

distinctive articles for The New Yorker for over five decades, and

through his famed creative nonfiction course, which he has long

taught at Princeton University, he has mentored many young writ-

ers who went on to enjoy their own distinctive careers, a list that

includes Richard Preston, Eric Schlosser, Jennifer Weiner, and Da-

vid Remnick. There’s no reasonable definition of productivity that

shouldn’t also apply to John McPhee, and yet nothing about his

work habits is frantic, busy, or overwhelming.

This initial insight developed into the core idea that this book

will explore: perhaps knowledge workers’ problem is not with pro-

ductivity in a general sense, but instead with a specific faulty def-

inition of this term that has taken hold in recent decades. The

relentless overload that’s wearing us down is generated by a belief

that “good” work requires increasing busyness—faster responses to

email and chats, more meetings, more tasks, more hours. But when

we look closer at this premise, we fail to find a firm foundation. I

came to believe that alternative approaches to productivity can be

just as easily justified, including those in which overfilled task lists

and constant activity are downgraded in importance, and some-

thing like John McPhee’s languid intentionality is lauded. Indeed,

it became clear that the habits and rituals of traditional knowledge

workers like McPhee were more than just inspiring, but could, with

sufficient care to account for the realities of twenty-first-century

jobs, provide a rich source of ideas about how we might transform

our modern understanding of professional accomplishment.

These revelations sparked new thinking about how we approach

our work, eventually coalescing into a fully formed alternative to

the assumptions driving our current exhaustion:

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 7 12/5/23 5:09 PM

8 | SLOW PRODUCTIVITY

SLOW PRODUCTIVITY

A philosophy for organizing knowledge work efforts in a

sustainable and meaningful manner, based on the follow-

ing three principles:

1. Do fewer things.

2. Work at a natural pace.

3. Obsess over quality.

As you’ll learn in the pages ahead, this philosophy rejects busy-

ness, seeing overload as an obstacle to producing results that mat-

ter, not a badge of pride. It also posits that professional efforts

should unfold at a more varied and humane pace, with hard peri-

ods counterbalanced by relaxation at many different timescales,

and that a focus on impressive quality, not performative activity,

should underpin everything. In the second part of this book, I’ll

detail the philosophy’s core principles, providing both theoretical

justification for why they’re right and concrete advice on how to

take action on them in your specific professional life, regardless of

whether you run your own company or work under the close su-

pervision of a boss.

My goal is not to simply offer tips about how to make your job

somewhat less exhausting. Nor is it to merely shake my metaphor-

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 8 12/5/23 5:09 PM

INTRODUCTION | 9

ical fist on your behalf at the exploitative fiends indifferent to your

stressed-out plight (though we’ll certainly do some of that). I want

to instead propose an entirely new way for you, your small busi-

ness, or your large employer to think about what it means to get

things done. I want to rescue knowledge work from its increasingly

untenable freneticism and rebuild it into something more sustain-

able and humane, enabling you to create things you’re proud of

without requiring you to grind yourself down along the way. Not

every office job, of course, will enjoy the ability to immediately

embrace this more intentional rhythm, but as I’ll detail, it’s more

widely applicable than you might at first guess. I want to prove to

you, in other words, that accomplishment without burnout not

only is possible, but should be the new standard.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, however, we must first under-

stand how the knowledge sector stumbled into its current mal-

functioning relationship with productivity in the first place, as it

will be easier to reject the status quo once we truly understand the

haphazardness of its formation. It’s toward the pursuit of this goal,

then, that we’ll now start our journey.

Slow_9780593544853_all_4p_r1.indd 9 12/5/23 5:09 PM

Pre-order the Book!

Pre-order Slow Productivity anywhere books are sold:

a a i o n.c o m l I BARNES&NOBLE

'--- -�_ _ _ _ _ _ _____.

�-B_A_M_!_�I I B Bookshop.org

Visit calNewport.com/slow for more information.

'' This brilliant and timely book is for all of us who've grown disillusioned

with conventional productivity advice, yet still yearn to get meaningful

things done. With his trademark blend of philosophical depth and realistic

techniques, Newport outlines an approach that's more human and vastly

more effective in the long run.

Oliver Burkeman

Author of Four Thousand Weeks

Cal Newport is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at

Georgetown University. His scholarship focuses on the theory of

distributed systems, while his general-audience writing explores

intersections of culture and technology. He is the author of eight

books, including, most recently, Slow Productivity, A World Without

Email, Digital Minimalism, and Deep Work. These titles include

multiple New York Times bestsellers and have been published in 40

languages. Newport is also a contributing writer for the New Yorker

and the host of the Deep Questions podcast.

www.CalNewport.com I www.TheDeepLife.com

You might also like

- Postmodernizm Ve Tanrının ÖlümüDocument55 pagesPostmodernizm Ve Tanrının Ölümüİrfan KOÇAKSOYNo ratings yet

- Global Environmental Politics PDFDocument209 pagesGlobal Environmental Politics PDFLo Long YinNo ratings yet

- The Smurfs and Magic FluteDocument81 pagesThe Smurfs and Magic FluteYzza Belle100% (1)

- Thesis KabukiDocument49 pagesThesis KabukiRyusuke SaburoNo ratings yet

- Religious Significance of ConcentrationDocument18 pagesReligious Significance of Concentrationabdul samad murshidNo ratings yet

- Leyla Erbil Öykülerinde Nesnellik Dil Ve AnlatımDocument133 pagesLeyla Erbil Öykülerinde Nesnellik Dil Ve AnlatımyahafizNo ratings yet

- Şukufe Ni̇hal - GayyaDocument41 pagesŞukufe Ni̇hal - GayyamsmsNo ratings yet

- Dakic UrosDocument99 pagesDakic UrosMarwa Omar100% (1)

- Eli̇f Şafak Mahrem - The GazeDocument244 pagesEli̇f Şafak Mahrem - The GazeMehmet ZamanNo ratings yet

- Mool Mantra: 52+1 RipetationDocument8 pagesMool Mantra: 52+1 RipetationCaterina MongilloNo ratings yet

- Sentences About Self-Reference & RecurrenceDocument3 pagesSentences About Self-Reference & RecurrencepronoysikdarNo ratings yet

- Kendiliğin Nöral Alt YapısıDocument13 pagesKendiliğin Nöral Alt YapısıSenem DalliogluNo ratings yet

- Fate, Free Will & The Law of KarmaDocument8 pagesFate, Free Will & The Law of Karmaakincana100% (1)

- Bringing Yoga To Life: The Everyday Practice of Enlightened Living - Donna FarhiDocument4 pagesBringing Yoga To Life: The Everyday Practice of Enlightened Living - Donna FarhilukefehiNo ratings yet

- Finding Your Maximum Flexibility in YogaDocument10 pagesFinding Your Maximum Flexibility in Yogaadaminindia26No ratings yet

- Falun Dafa VersesDocument10 pagesFalun Dafa VersesegmontsaffiNo ratings yet

- Gamma MeditationDocument4 pagesGamma Meditationfastz28camaro198175% (4)

- JOT Cue SheetsDocument53 pagesJOT Cue SheetsMukund KrishnaNo ratings yet

- How To Perform Higher KicksDocument46 pagesHow To Perform Higher Kicksfarhan.rafi2311No ratings yet

- The Zipline AdventureDocument1 pageThe Zipline AdventuremihaelahristeaNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving: Smart Training Resources India Pvt. Ltd. Smart Training Resources India Pvt. LTDDocument20 pagesProblem Solving: Smart Training Resources India Pvt. Ltd. Smart Training Resources India Pvt. LTDjohn cena100% (1)

- Epston 2016Document9 pagesEpston 2016Erick RomeroNo ratings yet

- RE IMAGINING NARRATIVE THERAPYAhistoryforthefutureDocument10 pagesRE IMAGINING NARRATIVE THERAPYAhistoryforthefutureValentín GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Mock Cat 3Document95 pagesMock Cat 3Sahil k0% (1)

- Practical Tips On Writing A Book From 23 Brilliant Authors NeuroTribesDocument34 pagesPractical Tips On Writing A Book From 23 Brilliant Authors NeuroTribesSunita K RamanathanNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Work in An Age of Uncertainty The Eroding Work Experience in America David L Blustein Full ChapterDocument62 pagesThe Importance of Work in An Age of Uncertainty The Eroding Work Experience in America David L Blustein Full Chaptermatthew.reed383100% (14)

- Houston, We Have a Narrative: Why Science Needs StoryFrom EverandHouston, We Have a Narrative: Why Science Needs StoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Promiscuous Knowledge: Information, Image, and Other Truth Games in HistoryFrom EverandPromiscuous Knowledge: Information, Image, and Other Truth Games in HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Myth of the First Three Years: A New Understanding of Early Brain Development andFrom EverandThe Myth of the First Three Years: A New Understanding of Early Brain Development andRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Metacognitive ReflectionDocument7 pagesMetacognitive Reflectionapi-311997496No ratings yet

- The Queen Must Live: Mythic Patterns of Royalty, Sexuality, and MortalityFrom EverandThe Queen Must Live: Mythic Patterns of Royalty, Sexuality, and MortalityNo ratings yet

- Mock Cat 3Document114 pagesMock Cat 3Pradipto DeNo ratings yet

- Mastering the Moment: Perfecting the Skills and Processes of Exceptional Presentation DeliveryFrom EverandMastering the Moment: Perfecting the Skills and Processes of Exceptional Presentation DeliveryNo ratings yet

- Words Unspoken: The Science, Experience, and Treatment of StutteringFrom EverandWords Unspoken: The Science, Experience, and Treatment of StutteringNo ratings yet

- The Writer's Survival Guide: An Instructive, Insightful Celebration of the Writing LifeFrom EverandThe Writer's Survival Guide: An Instructive, Insightful Celebration of the Writing LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Heartful Art of Revision: An Intuitive Guide to EditingFrom EverandThe Heartful Art of Revision: An Intuitive Guide to EditingNo ratings yet

- The Human Scaffold: How Not to Design Your Way Out of a Climate CrisisFrom EverandThe Human Scaffold: How Not to Design Your Way Out of a Climate CrisisNo ratings yet

- Module 4 English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument10 pagesModule 4 English For Academic and Professional PurposesReyman Andrade LosanoNo ratings yet

- Paul A. Roth (Author) - The Philosophical Structure of Historical Explanation-Northwestern University Press (2019)Document209 pagesPaul A. Roth (Author) - The Philosophical Structure of Historical Explanation-Northwestern University Press (2019)Lucas Agustin Perez PicassoNo ratings yet

- Motivate Your Writing: Using Motivational Psychology to Energize Your Writing LifeFrom EverandMotivate Your Writing: Using Motivational Psychology to Energize Your Writing LifeNo ratings yet

- Jewcentricity: Why the Jews Are Praised, Blamed, and Used to Explain Just About EverythingFrom EverandJewcentricity: Why the Jews Are Praised, Blamed, and Used to Explain Just About EverythingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Evolution and The BibleDocument86 pagesEvolution and The BibleMichael Schuyler100% (1)

- Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of CounterintuitionFrom EverandThink Twice: Harnessing the Power of CounterintuitionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Kiran Kumari: Effect of Covid-19 - Student'S LifeDocument3 pagesKiran Kumari: Effect of Covid-19 - Student'S Lifemadhav agarwalNo ratings yet

- Jennifer Papies DissertationDocument5 pagesJennifer Papies DissertationPaperWriterOnlineCharleston100% (1)

- Men Can: The Changing Image and Reality of Fatherhood in AmericaFrom EverandMen Can: The Changing Image and Reality of Fatherhood in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Between Dreaming and Recognition Seeking: The Emergence of Dialogical Self TheoryFrom EverandBetween Dreaming and Recognition Seeking: The Emergence of Dialogical Self TheoryNo ratings yet

- Battle for the American Mind: Uprooting a Century of MiseducationFrom EverandBattle for the American Mind: Uprooting a Century of MiseducationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- A Radical Political Theology for the Anthropocene Era: Thinking and Being OtherwiseFrom EverandA Radical Political Theology for the Anthropocene Era: Thinking and Being OtherwiseNo ratings yet

- The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNAFrom EverandThe Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNARating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- Mge - Ex11rt - Installation and User Manual PDFDocument38 pagesMge - Ex11rt - Installation and User Manual PDFRafa TejedaNo ratings yet

- Blank Freeway Walls Replaced With Local Designs - Press EnterpriseDocument5 pagesBlank Freeway Walls Replaced With Local Designs - Press EnterpriseEmmanuel Cuauhtémoc Ramos BarajasNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Excavator: Engine WeightsDocument28 pagesHydraulic Excavator: Engine WeightsFelipe Pisklevits LaubeNo ratings yet

- OSX ExpoDocument13 pagesOSX ExpoxolilevNo ratings yet

- Opentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideDocument38 pagesOpentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideDoond adminNo ratings yet

- RL78 L1B UsermanualDocument1,062 pagesRL78 L1B UsermanualHANUMANTHA RAO GORAKANo ratings yet

- Epson EcoTank ITS Printer L4150 DatasheetDocument2 pagesEpson EcoTank ITS Printer L4150 DatasheetWebAntics.com Online Shopping StoreNo ratings yet

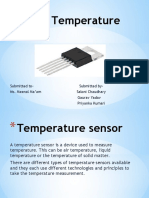

- Topic - Temperature SensorDocument9 pagesTopic - Temperature SensorSaloni ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Emulsion LectureDocument30 pagesEmulsion LectureRay YangNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Marketing - Week 1Document7 pagesAn Overview of Marketing - Week 1Jowjie TVNo ratings yet

- QFW Series SteamDocument8 pagesQFW Series Steamnikon_fa50% (2)

- Fisker Karma - Battery 12V Jump StartDocument2 pagesFisker Karma - Battery 12V Jump StartRedacTHORNo ratings yet

- Oxygenation - NCPDocument5 pagesOxygenation - NCPCazze SunioNo ratings yet

- R917007195 Comando 8RDocument50 pagesR917007195 Comando 8RRodrigues de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Baumer Tdp02 Tdpz02 Ds enDocument4 pagesBaumer Tdp02 Tdpz02 Ds enQamar ZiaNo ratings yet

- Rizal Noli Me TangereDocument35 pagesRizal Noli Me TangereKristine Cantilero100% (2)

- Attitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationDocument9 pagesAttitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- DCNF Vs Hhs Nov 2020Document302 pagesDCNF Vs Hhs Nov 2020SY LodhiNo ratings yet

- First Semester-NOTESDocument182 pagesFirst Semester-NOTESkalpanaNo ratings yet

- 3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Document66 pages3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Nikhil GampaNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 1 POMDocument10 pagesAssignment # 1 POMnaeemNo ratings yet

- EVS (Yuva)Document88 pagesEVS (Yuva)dasbaldev73No ratings yet

- Classroom Activty Rubrics Classroom Activty Rubrics: Total TotalDocument1 pageClassroom Activty Rubrics Classroom Activty Rubrics: Total TotalMay Almerez- WongNo ratings yet

- Weather Prediction Using Machine Learning TechniquessDocument53 pagesWeather Prediction Using Machine Learning Techniquessbakiz89No ratings yet

- Capacitor Trip Device CTD-4Document2 pagesCapacitor Trip Device CTD-4DAS1300No ratings yet

- Btech CertificatesDocument6 pagesBtech CertificatesSuresh VadlamudiNo ratings yet

- Open Book Online: Syllabus & Pattern Class - XiDocument1 pageOpen Book Online: Syllabus & Pattern Class - XiaadityaNo ratings yet

- Section ADocument7 pagesSection AZeeshan HaiderNo ratings yet

- LANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsDocument2 pagesLANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsAnneNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument2 pagesIndustrial RevolutionDiana MariaNo ratings yet