Professional Documents

Culture Documents

15 20a Bartelink

Uploaded by

980Denis FernandezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

15 20a Bartelink

Uploaded by

980Denis FernandezCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Whole-breast irradiation with or without a boost for patients

treated with breast-conserving surgery for early breast

cancer: 20-year follow-up of a randomised phase 3 trial

Harry Bartelink, Philippe Maingon, Philip Poortmans, Caroline Weltens, Alain Fourquet, Jos Jager, Dominic Schinagl, Bing Oei, Carla Rodenhuis,

Jean-Claude Horiot, Henk Struikmans, Erik Van Limbergen, Youlia Kirova, Paula Elkhuizen, Rudolf Bongartz, Raymond Miralbell, David Morgan,

Jean-Bernard Dubois, Vincent Remouchamps, René-Olivier Mirimanoff, Sandra Collette, Laurence Collette; on behalf of the European Organisation

for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiation Oncology and Breast Cancer Groups

Summary

Background Since the introduction of breast-conserving treatment, various radiation doses after lumpectomy have Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 47–56

been used. In a phase 3 randomised controlled trial, we investigated the effect of a radiation boost of 16 Gy on overall Published Online

survival, local control, and fibrosis for patients with stage I and II breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving December 9, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

treatment compared with patients who received no boost. Here, we present the 20-year follow-up results.

S1470-2045(14)71156-8

This online publication has

Methods Patients with microscopically complete excision for invasive disease followed by whole-breast irradiation of been corrected.

50 Gy in 5 weeks were centrally randomised (1:1) with a minimisation algorithm to receive 16 Gy boost or no boost, The corrected version first

with minimisation for age, menopausal status, presence of extensive ductal carcinoma in situ, clinical tumour size, appeared at thelancet.com/

oncology on

nodal status, and institution. Neither patients nor investigators were masked to treatment allocation. The primary

December 29, 2014

endpoint was overall survival in the intention-to-treat population. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov,

See Comment page 5

number NCT02295033.

Department of Radiation

Oncology, The Netherlands

Findings Between May 24, 1989, and June 25, 1996, 2657 patients were randomly assigned to receive no radiation boost Cancer Institute, Amsterdam,

and 2661 patients randomly assigned to receive a radiation boost. Median follow-up was 17·2 years (IQR 13·0–19·0). Netherlands (H Bartelink MD,

20-year overall survival was 59·7% (99% CI 56·3–63·0) in the boost group versus 61·1% (57·6–64·3) in the no boost P Elkhuizen MD); Department of

Radiation Oncology, Centre

group, hazard ratio (HR) 1·05 (99% CI 0·92–1·19, p=0·323). Ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence was the first Georges-Francois Leclerc,

treatment failure for 354 patients (13%) in the no boost group versus 237 patients (9%) in the boost group, HR 0·65 Dijon, France (P Maingon MD);

(99% CI 0·52–0·81, p<0·0001). The 20-year cumulative incidence of ipsilatelal breast tumour recurrence was 16·4% Department of Radiation

(99% CI 14·1–18·8) in the no boost group versus 12·0% (9·8–14·4) in the boost group. Mastectomies as first salvage Oncology, Institute Verbeeten,

Tilburg, Netherlands

treatment for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence occurred in 279 (79%) of 354 patients in the no boost group versus (P Poortmans MD, B Oei MD);

178 (75%) of 237 in the boost group. The cumulative incidence of severe fibrosis at 20 years was 1·8% (99% CI Department of Radiation

1·1–2·5) in the no boost group versus 5·2% (99% CI 3·9–6·4) in the boost group (p<0·0001). Oncology, KU Leuven,

University Hospitals Leuven,

Belgium (C Weltens MD,

Interpretation A radiation boost after whole-breast irradiation has no effect on long-term overall survival, but can E Van Limbergen MD);

improve local control, with the largest absolute benefit in young patients, although it increases the risk of moderate to Department of Radiation

severe fibrosis. The extra radiation dose can be avoided in most patients older than age 60 years. Oncology, Institut Curie, Paris,

France (A Fourquet MD,

Y Kirova MD); Department of

Funding Fonds Cancer, Belgium. Radiation Oncology, Maastro

Clinic, Maastricht, Netherlands

Introduction breast tumour recurrence was reduced in patients who (J Jager MD); Department of

Radiation Oncology, Radboud

Radiotherapy after breast-conserving treatment halves received the boost dose.2 The largest absolute

University Medical Center,

the chance of disease recurrence and reduces breast improvement occurred in patients aged 40 years or less. Nijmegen, Netherlands

cancer mortality by about a sixth.1 However, uncertainty 10-year follow-up showed a favourable result in the (D Schinagl MD, P Poortmans);

remains as to the radiation dose needed for patients boost group in terms of ipsilateral breast recurrence, Department of Radiation

Oncology, Medical Center

treated with lumpectomy for early breast cancer. For with no significant interaction by age group.3 As a result,

Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

this reason, the European Organisation for Research the number of salvage mastectomies was substantially (C Rodenhuis MD,

and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) did a phase 3 reduced. However, severe fibrosis in the tumour bed H Struikmans MD); Clinique de

randomised trial2 investigating the potential advantage area was more common in the boost group than in the Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

(J-C Horiot MD); Department of

of delivering a higher radiation dose to the tumour bed no boost group. 10-year overall survival did not differ

Radiation Oncology,

after whole-breast irradiation of 50 Gy in 5 weeks. significantly between groups. Universitaetsklinikum Köln,

5318 patients with microscopically complete excision Romestaing and colleagues4 also investigated the effect Köln, Germany

followed by whole-breast irradiation of 50 Gy were of a boost dose in a trial including 1024 patients who (R Bongartz MD); Division of

Radiation Oncology, Hôpitaux

randomly assigned to receive either a boost dose of received a boost of 10 Gy to the tumour bed after 50 Gy Universitaires de Genève,

16 Gy or no boost dose. The preliminary analysis after delivered with 2·5 Gy per fraction to the whole breast Geneva, Switzerland

5 years’ follow-up suggested that the risk of ipsilateral following limited surgery. They found that this approach (R Miralbell MD); Department

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015 47

Articles

of Clinical Oncology, significantly reduced the risk of early ipsilateral breast Randomisation and masking

Nottingham University tumour recurrence, with no serious deterioration of the Patients who had received microscopically complete

Hospitals NHS Trust,

Nottingham, UK

cosmetic result. excision of a breast tumour (no invasive disease at the

(D Morgan MD); Institut We assessed whether the initial benefit of a boost inked margin of the surgical specimen according to the

Régional du Cancer dose, resulting in improved local control, is sustained in local pathologist) and axillary dissection, followed by

Montpellier, Montpellier, the very long term in patients with stage I and II breast whole-breast irradiation of 50 Gy in 5 weeks, were

France (J-B Dubois MD);

Department of Radiotherapy,

cancer who underwent breast-conserving treatment and centrally randomised at the EORTC headquarters

Clinique et Maternité Sainte whether this benefit translates into an improvement in according to a minimisation algorithm5 (variance

Elisabeth, Namur, Belgium survival. method) in a 1:1 ratio to receive either no extra

(V Remouchamps MD); Clinique irradiation or a boost dose of 16 Gy aimed at the original

La Source, Lausanne,

Switzerland

Methods tumour bed (appendix). Patients with a microscopically

(R-O Mirimanoff MD); and Study design and patients incomplete excision were randomly assigned to boost

EORTC Headquarters, Brussels, We analysed the long-term results from the EORTC doses of 10 Gy or 26 Gy; these patients are not included

Belgium (S Collette MSc,

phase 3 randomised controlled trial.3 The trial was done at further in this report, but have been reported

L Collette PhD)

31 hospitals and medical centres in Australia, Belgium, elsewhere.6

Correspondence to:

Dr Harry Bartelink, Department

France, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Factors used in the minimisation were age, menopausal

of Radiation Oncology, The and the UK. The protocol is available online. status, presence of extensive ductal carcinoma in situ

Netherlands Cancer Institute, Patients with T1–2, N0–1, and M0 breast cancer (ten or more ducts involved), clinical tumour size, nodal

Plesmanlaan 121, (stage I and II breast cancer) who had undergone status, and institute where the patient received treatment.

1066 CX Amsterdam,

Netherlands

macroscopically complete local excision of the breast Neither patients nor investigators were masked to

h.bartelink@nki.nl tumour and axillary dissection were eligible for the treatment allocation.

trial. Patients were ineligible if they were older than

See Online for appendix 70 years, if they had pure carcinoma in situ, multiple Procedures

tumour foci in more than one quadrant, a history of Patients had to undergo surgical excision of the primary

For the protocol see http:// other malignant disease, an Eastern Cooperative tumour, with a 1–2 cm margin of macroscopically normal

research.nki.nl/ibr/protocols/ Oncology Group performance score higher than 2, tissue and an axillary dissection.2 Any removal of

EORTC-22881-10882-Boost-no-

Boost.pdf

residual microcalcifications on mammography, additional breast tissue after excision of the primary

concurrent pregnancy or lactation, or if a tumourectomy tumour was termed a re-excision, whether it was done

was done more than 9 weeks before the start of during the same session or later. Patients with axillary

radiotherapy, and more than 6 months before the start lymph node involvement received adjuvant systemic

of radiotherapy if chemotherapy was given. Ineligible treatment: premenopausal patients received chemo-

patients were included in the analyses. The resection therapy and postmenopausal patients received tamoxifen

margins were assessed for the presence of invasive (20 mg per day for 2 years). Patients not given adjuvant

carcinoma, but not for ductal carcinoma in situ. Oral chemotherapy began radiotherapy within 9 weeks after

informed consent was obtained according to EORTC lumpectomy.

guidelines and the local and national rules of the Irradiation of the whole breast was done with two

participating institutes. Ethics committees of the tangential opposing megavoltage photon beams (high-

participating institutes approved the protocol. energy x-ray or tele-cobalt). A total dose of 50 Gy during

a 5-week period, with a dose of 2 Gy in 25 fractions, was

delivered at the intersection of the central axes of the

beams, in agreement with International Commission of

5569 patients underwent lumpectomy Radiation Units and Measurements report 50.7 The

boost dose was 16 Gy in eight fractions delivered with

electrons or oblique wedged photon beams, or 15 Gy

delivered with with an ¹⁹²Ir implant at a dose rate of

251 had incomplete resection 5318 randomly assigned after

complete resection 0·5 Gy per h (a 15 Gy internal dose is equivalent to a 16

Gy external dose). The choice between internal and

external dose was at the discretion of the treating

physician. The dose for the boost was specified at the

2657 assigned to no boost group (including 2661 assigned to boost group (including

17 ineligible) 10 ineligible) centre of the tumour excision area (point B; appendix).

2584 received no boost (including 8 ineligible) 2618 received no boost (including 7 ineligible) No dose reductions were allowed.

54 received a boost (including 5 ineligible) 26 received no boost (including 2 ineligible)

19 not irradiated at all (including 4 ineligible) 17 not irradiated at all (including 1 ineligible)

Patients were followed up two or three times per year

for 5 years, then once per year by mammography and

clinical examination including scoring of fibrosis. At

2657 included in intention-to-treat analysis 2661 included in analysis each visit except baseline, the physician scored the grade

of fibrosis (none, minor, moderate, or severe) for the

Figure 1: Trial profile whole breast and for the boost area.

48 www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015

Articles

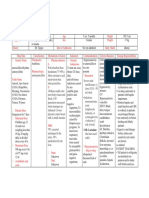

No boost group Boost group No boost group Boost group

(n=2657) (n=2661) (n=2657) (n=2661)

Age (years) 54·9 (47·3–62·0) 54·8 (47·1–62·6) (Continued from previous column)

≤35 72 (3%) 82 (3%) Largest diameter dominant legion

35–40 156 (6%) 139 (5%) Unknown 49 (2%) 62 (2%)

41–50 665 (25%) 669 (25%) <10 mm 683 (26%) 635 (24%)

51–60 943 (356%) 860 (32%) 10–20 mm 1402 (53%) 1451 (55%)

>60 821 (31%) 911 (34%) >20 mm 523 (20%) 513 (19%)

Menopausal status Histological type

Unknown 10 (<1%) 8 (<1%) Unknown 8 (0%) 8 (<1%)

Premenopausal 999 (38%) 1004 (38%) Invasive ductal 2155 (81%) 2198 (83%)

Menopausal 1648 (62%) 1649 (62%) carcinoma

Performance status Invasive lobular 228 (9%) 219 (8%)

carcinoma

Unknown 10 (<1%) 9 (<1%)

Mixed invasive pattern 65 (2%) 81 (3%)

0 2335 (88%) 2335 (88%)

Tubular carcinoma 99 (4%) 71 (3%)

1–2 312 (12%) 317 (12%)

Medullary carcinoma 58 (2%) 49 (2%)

Tumour characteristics

Colloid carcinoma 37 (1%) 33 (1%)

T palpation

Other 7 (<1%) 2 (<1%)

Unknown 336 (13%) 348 (13%)

Number of nodes examined

Not palpable 569 (21%) 581 (22%)

Unknown 69 (3%) 75 (3%)

<1 cm 315 (12%) 313 (12%)

0 21 (1%) 16 (1%)

1–2 cm 856 (32%) 829 (31%)

1–5 170 (6%) 176 (7%)

2–3 cm 433 (16%) 449 (17%)

6–10 813 (31%) 826 (31%)

>3 cm 148 (6%) 141 (5%)

11–15 876 (33%) 914 (34%)

Mammography

>15 708 (27%) 654 (25%)

<1 cm 576 (22%) 525 (20%)

Number of positive nodes

1–2 cm 1027 (39%) 1067 (40%)

Unknown 25 (1%) 20 (1%)

2–3 cm 397 (15%) 436 (16%)

0 2078 (78%) 2090 (79%)

>3 cm 110 (4%) 104 (4%)

1–3 452 (17%) 449 (17%)

Unknown 547 (21%) 529 (20%)

≥4 102 (4%) 102 (4%)

Clinical staging

Hormone receptor status*

T stage

Oestrogen receptor 1031 (39%) 1042 (39%)

T1 1379 (52%) 1373 (52%) positive, progesterone

T2 1274 (48%) 1281 (48%) receptor positive

T3 4 (<1%) 7 (<1%) Oestrogen receptor 255 (10%) 267 (10%)

N stage positive, progesterone

receptor negative

N0 2409 (91%) 2383 (90%)

Oestrogen receptor 133 (5%) 141 (5%)

N1–2 182 (7%) 209 (8%) negative, progesterone

Nx 66 (3%) 69 (3%) receptor positive

Pathological staging Oestrogen negative, 345 (13%) 358 (14%)

Re-exision progesterone receptor

negative

Unknown 8 (<1%) 8 (<1%)

Unknown 893 (34%) 853 (32%)

No 2003 (75%) 1991 (75%)

Yes 646 (24%) 662 (25%) Data are median (IQR) or n (%). *Oestrogen receptor status determined according

to local procedures by either charcoal or immunohistochemistry.

(Table continues in next column)

Table: Patient and tumour characteristics

Outcomes metastasis, analysis of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence

The primary endpoint was overall survival. Survival was by age, analysis of fibrosis by age, disease-free survival,

counted from the date of randomisation to date of death and overall survival after local failure. Time to ipsilateral

from any cause, or to last visit. For breast cancer mortality, breast tumour recurrence as first treatment failure was

other causes of death were analysed as competing risks. defined as the time from day of randomisation (instead of

Secondary outcomes were local control (ipsilateral breast date of surgery as mentioned in the original protocol to

tumour recurrence), cosmesis, and fibrosis. Exploratory reduce the risk of bias) to the day of first recurrence, or to

endpoints were breast cancer mortality, time to distant the day of last visit for patients alive and free of recurrence.

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015 49

Articles

Ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence as the first treatment the first ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence for all

failure was the event of interest and any other treatment patients with local ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence as

failure as first event (including death) was considered a first failure. Disease-free survival was the time from day

competing risk. Time to distant metastases was defined as of first report of local ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence,

the time from randomisation to the first report of distant to the day of first report of either a subsequent local

metastases (event), death without metastases (competing failure or a failure at another site or to death of any cause.

risk), or last visit (censored observation). Similarly, time to Cumulative incidence of severe fibrosis was counted

second primary cancer was defined as the time from from entry to the date of first report of severe fibrosis or

randomisation to the first report of second primary, death until the last visit before a mastectomy. Mastectomy and

without the event of interest (competing risk), or last visit death without severe fibrosis were competing risks for

(censored observation). this analysis.

For the analyses of overall survival and disease-free

survival after local failure, time to event was counted from Statistical analysis

Initially, the endpoint of interest was the cosmetic effect,

100

with 90% confidence that the difference in ipsilateral

No boost

Boost breast tumour recurrence did not differ between groups

90 by more than 5%. However, after 3 years, the study was

80 enlarged and survival was added as the primary endpoint

to show a difference of 5% in 10-year overall survival

70

(from 80% to 85%, hazard ratio [HR] 0·728) with a power

Overall survival (%)

60 of 90% and a significance level of 1% using a two-sided

log-rank test. Local control, cosmesis, and fibrosis were

50

also added as secondary endpoints. 960 deaths were

40 needed to provide adequate power for the test, with

30

5000 patients to be recruited (appendix).2

All tests were done at the two-sided 0·01 significance

20 level. The analyses were by intention to treat. Survival was

10 HR 1·05 (99% CI 0·92–1·19) estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared with a

p=0·323 log-rank test;8 cumulative incidences of ipsilateral breast

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 tumour recurrence, distant metastases, second primary

Number at risk

Time (years) cancers, breast-cancer mortality, and fibrosis were

No boost 2657 2332 1878 1331 241 compared with Fine and Gray tests.9 We estimated HRs

Boost 2661 2361 1867 1302 223 and 99% CIs with Cox models for endpoints not subject

Figure 2: Overall survival

to competing risks, and we estimated competing risk-

HR=hazard ratio. adjusted HRs and 99% CIs from Fine and Gray models.9

The analyses were done with SAS computer software

100 No boost (version 9.4).

Boost The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number

90

NCT02295033.

80

70

Role of the funding source

The funder had no role in the study design, data

Recurrence (%)

60 collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of

50 the report. The corresponding author had full access to

all the data in the study and had final responsibility for

40

Competing risks HR

the decision to submit for publication.

30 HR 0·65 (99% CI 0·52–0·81)

20

p<0·0001 Results

Between May 24, 1989, and June 25, 1996, 5569 participants

10 with early stage breast cancer underwent a lumpectomy

0

followed by whole-breast irradiation of 50 Gy. 5318 patients

0 5 10 15 20 25 had microscopically complete tumour excision and were

Time (years)

Number at risk randomly assigned—2661 to the boost group and 2657 to

No boost 2657 2021 1492 970 160 the no boost group (figure 1). 251 patients with

Boost 2661 2063 1500 970 163

microscopically incomplete excision were randomly

Figure 3: Ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence assigned to a boost dose of 10 Gy or 26 Gy—however,

HR=hazard ratio. these results have been described elsewhere6 and will not

50 www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015

Articles

A B

100 No boost HR 0·56 (99% CI 0·34–0·92); p=0·003 HR 0·66 (99% CI 0·45–0·98); p=0·007

Boost

90

80

70

Recurrence (%)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 25

Number at risk

No boost 228 149 111 79 14 665 493 375 258 54

Boost 221 149 112 75 14 669 515 382 264 64

C D

100 HR 0·69 (99% CI 0·46–1·04); p=0·020 HR 0·66 (99% CI 0·42–1·04); p=0·019

90

80

70

Recurrence (%)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 25

Time (years) Time (years)

Number at risk

No boost 943 752 566 373 61 821 627 440 260 31

Boost 860 687 513 333 48 911 712 493 298 37

Figure 4: Cumulative incidence of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence by age

For patients aged ≤40 years, 71 patients in the no boost group versus 42 in the boost group had recurrence (A); for patients aged 41–50 years, 108 versus 74 had recurrence (B); for patients aged

51–60 years, 100 versus 64 had recurrence (C); and for patients aged >60 years, 75 versus 57 had recurrence (D). HR=hazard ratio.

be considered further in this report. 26 patients assigned in more than one quadrant (three vs three; appendix); but

to the boost group did not receive the boost (16 refused, all patients were included in the analyses.

four because of administration errors, two because of The main reasons for deviation from treatment allocation

microcalcification, two because of metastases, one had were patient choice and administrative error. Median

psychiatric problems, and one because of dermolysis follow-up of patients with complete resection was

during whole-breast irradiation), whereas 54 patients 17·2 years (IQR 13·0–19·0) and median age of the patients

assigned to the no boost group received a boost (19 in at treatment was 55 years (47–62). Patient characteristics

error, 13 for medical decision [eg, disease extension, more were similar in the two groups (table): 90% of patients

advanced stage, incomplete resection], 22 because of were clinically N0 and 78% were pathologically N0. Surgery

patient request). or whole-breast irradiation differed little between groups

Reasons for ineligibility were different histology (four (appendix). 225 (8%) of 2661 patients in the boost group

patients in the no boost group vs two in the boost group), received an interstitial boost at a median dose of 15 Gy

microcalcifications on postoperative mammogram (four (IQR 15–15), whereas 2393 (90%) of 2661 received an

vs three), previous malignancy (four vs three), incomplete external boost at a median dose of 16 Gy (IQR 16–16).

surgery (one vs none), and higher TNM stage or tumour 17 received no irradiation at all (five had no information on

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015 51

Articles

treatment, six refued, three because of medical decision p=0·323; figure 2). Cumulative incidence of breast

based on microcalcification, metastases, or age, and three cancer mortality did not differ significantly between

in error). groups (447 events vs 456 events, HR 1·01, 99% CI

Use of chemotherapy or tamoxifen as adjuvant 0·86–1·20, p=0·82). The cumulative risk of distant

treatment did not differ significantly between groups metastases did not differ significantly (568 events vs

(appendix). However, in premenopausal patients with 602 events); risk of distant relapse at 20 years was

positive lymph nodes, chemotherapy was prescribed 24·8% (99% CI 22·3–27·4) in the no boost group versus

more often in the boost group than in the no boost group 26·0% (23·4–28·7) in the boost group (HR 1·06,

(197 [87·6%] of 225 vs 174 [78·7%] of 221). 99% CI 0·92–1·24; p=0·29). We recorded no significant

799 (30%) of 2657 patients died in the no boost group difference in the cumulative incidence of second

versus 832 (31%) of 2661 patients in the boost group. primary tumour in the contralateral breast (208 in the

20-year overall survival was 61·1% in the no boost no boost group vs 232 in the boost group), or at sites

group (99% CI 57·6–64·3) versus 59·7% in the boost other than the breast (216 vs 240; appendix). There was

group (56·3–63·0; HR 1·05, 99% CI 0·92–1·19, also no difference in overall incidence of breast

A B

100 No boost HR 1·02 (99% CI 0·17–6·22); p=0·98 HR 3·51 (99% CI 1·16–10·55); p=0·003

Boost

90

80

70

Severe fibrosis (%)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 25

Number at risk

No boost 221 159 123 87 14 644 533 412 293 60

Boost 217 167 134 93 15 666 554 419 295 69

C D

100 HR 3·15 (99% CI 1·49–6·65); p<0·001 HR 2·55 (99% CI 1·24–5·27); p<0·001

90

80

70

Severe fibrosis (%)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 5 10 15 20 25 0 5 10 15 20 25

Time (years) Time (years)

Number at risk

No boost 920 783 615 419 75 799 663 476 293 32

Boost 857 734 571 394 62 904 750 546 341 41

Figure 5: Cumulative incidence of severe fibrosis by age

For patients aged ≤40 years, four patients in the no boost group versus four in the boost group had severe fibrosis (A); for patients aged 41–50 years, seven versus 25 had severe fibrosis (B); for patients

aged 51–60 years, 16 versus 46 had severe fibrosis (C); and for patients aged >60 years, 17 versus 49 had severe fibrosis (D). HR=hazard ratio.

52 www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015

Articles

cancer-related events, disease-free survival, or time to 100 Overall survival

any recurrence (appendix). Disease-free survival

90

Local breast recurrence was first failure for 354 (13%)

patients in the no boost group versus 237 (9%) patients 80

in the boost group (figure 3); any locoregional failure 70

occurred in 480 versus 352 patients. Ipsilateral breast

60

tumour recurrence increased in both treatment groups:

Survival (%)

from 10·2% (99% CI 8·7–11·8) at 10 years to 16·4% 50

(14·1–18·8) at 20 years for the no boost group, and from 40

6·4% (5·2–7·7) to 12·0% (9·8–14·4) for the boost group.

30

The HR for an ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence as a

first event was 0·65 (99% CI 0·52–0·81, p<0·0001). 20

Patients’ age was strongly correlated with the absolute 10

risk of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence. 20-year

0

cumulative incidence ranged from 34·5% (99% CI 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21

21·9–47·2) for patients 35 years or younger, to 11·1% Time (years)

(7·6–14·6) for patients older than 60 years (appendix). Number at risk

Disease-free survival 591 307 211 141 82 35 8

The relative reduction of risk by giving a boost dose was Overall survival 591 417 288 188 113 47 12

significant for younger age groups (for age ≤40 years,

p=0·003; and for age 41–50 years, p=0·007) but not for Figure 6: Overall survival and disease-free survival after local failure

the two older age groups (for age 51–60 years, p=0·02; for The drop of the curve at 0 years is a result of 34 patients who had ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence with failure at

another site as the first event. For both endpoints, censoring was done at the date of last visit.

age >60 years, p=0·019); the effect was not significantly

different by age group (pinteraction=0·67; figure 4, appendix).

The absolute risk reduction was largest in the youngest group than in the no boost group for all age groups except

patient group: 20-year risk was 36·0% (99% CI patients younger than 41 years (figure 5). Moderate or

25·8–46·2) in the no boost group versus 24·4% severe fibrosis was also more common in the boost group

(14·9–33·8) in the boost group for patients younger than versus the no boost group, with a 20-year cumulative

40 years; 19·4% (14·7–24·1%) versus 13·5% (9·5–17·5) incidence of 30·4% (99% CI 28·0–32·9) versus 15·0%

for patients aged 41–50 years; 13·2% (9·8–16·7) versus (13·0–17·1; p<0·0001). The cumulative incidence of any

10·3% (6·3–14·3) for patients aged 51–60 years; and degree of fibrosis (minor, moderate, or severe) was 71·4%

12·7% (CI 7·4–18·0) versus 9·7% (5·0–14·4) for patients (69·0–73·7) versus 57·2% (54·6–59·8; p<0·0001).

older than 60 years (figure 4). Results for ipsilateral Salvage treatment for a breast recurrence was done for

breast tumour recurrence were essentially unchanged 354 (13%) patients in the no boost group and 237 (9%)

when adjusted for baseline factors and other treatments patients in the boost group. Mastectomy was the initial

(data not shown). Overall, 261 (44%) of 591 ipsilateral salvage treatment for ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence

breast tumour recurrences occurred in the primary for 457 patients (279 [79%] of 354 in the no boost group

tumour bed, 47 (8%) of 591 occurred in the scar, 66 (11%) and 178 [75%] of 237 in the boost group). The cumulative

of 591 were diffuse in the breast, 165 (28%) of 591 incidence of salvage mastectomy at 10 years was 6·4%

occurred outside the original tumour area, and for 52 (99% CI 5·2–7·7) for the boost group and 10·3%

(9%) of 591 location was not specified (appendix). The (8·7–11·8) for the no boost group.

type of boost did not have a significant effect on the Lumpectomy was the salvage treatment for 52 patients

cumulative incidence of ipsilateral breast tumour (32 [1%] in the no boost group vs 20 [1%] in the boost

recurrence, whether it was given by electrons, ⁶⁰Co, group). The salvage treatment in the remaining

megavoltage x-rays, or ¹⁹²Ir boost (appendix). Regional 69 patients (38 [1%] in the boost group vs 31 [1%] in the

recurrence in the axilla or supraclavicular area was the no boost group) was mainly systemic chemotherapy. No

first event in 66 (2%) patients in the no boost group information about salvage treatment was obtained for

versus 59 (2%) patients in the boost group. five patients in the no boost group and eight in the

Second primary ipsilateral breast cancers (different boost group. For patients in both groups together, at

histology compared with the primary tumour) occurred 10 years after local relapse, disease-free survival

in 51 patients (30 [1%] in the no boost group vs 21 [1%] in (counted from local relapse to any next failure) was

the boost group; appendix). Second primary contralateral 42·0% (99% CI 35·9–48·0) and overall survival

breast cancers occurred in 440 patients (208 [8%] in the was 57·0% (99% CI 50·4–63·0; figure 6).

no boost vs 232 [9%] in the boost group).

The cumulative incidence of severe fibrosis at 20 years Discussion

was 5·2% (99% CI 3·9–6·4) in the boost group versus 20 years after breast-conserving treatment, about 60% of

1·8% (1·1–2·5) in the no boost group (p<0·0001; patients with breast cancer were still alive, but survival

appendix). Severe fibrosis was more common in the boost did not differ between patients who received or did not

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015 53

Articles

receive a boost of 16 Gy after whole-breast irradation. colleagues,4 in which patients were treated with external

However, a boost dose did reduce the incidence of irradiation and that by Polgar and colleagues,18 in which

ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence. patients received boost with an iridium implant.

The failure of improved local control to improve breast The site of local recurrence was, in almost half of

cancer mortality or overall survival seems contradictory to patients, in the primary tumour bed (appendix), which

the findings of the EBCTCG trial.1 However, in our study supports use of an non-uniform dose distribution, with

only about 20% of patients were node positive; in the the highest dose directed to the primary tumour site. The

EBCTCG trial the survival benefit of radiotherapy was survival of patients after ipsilateral breast recurrence was

recorded in node-positive patients. Nevertheless, we high. The success of the salvage treatment will be

detected no substantial difference in survival in relation investigated further.

to nodal status (data not shown), or first time to any The local recurrence rate in our study was higher than

recurrence. The most likely explanation is successful that reported in other studies, such as the Young Boost

salvage mastectomy treatment for these breast Trial,14 which reported 5-year local recurrence rates as low

recurrences, as reported in a previous trial in which the as 1·2% in patients younger than 51 years. Similar local

high rate of local recurrence in the breast-conserving control rates were reported in the control groups of trials

treatment group compared with the mastectomy group comparing whole-breast irradiation with partial breast

did not affect survival (panel).13 irradiation.19,20 Possible explanations for the lower rate in

The relative benefit of the boost dose for local control other trials are better preoperative staging imaging

was independent of age, but with increasing age the procedures, use of image-guided surgery with pathological

absolute gain in local control decreased (in proportion to assessment of the margins, optimised radiotherapy with

the absolute risk of relapse) but remained statistically 3D treatment planning, and more widespread use of

significant. Younger patients had more ipsilateral breast effective adjuvant systemic treatment. 80% of patients

tumour recurrences than older patients, as reported in received adjuvant systemic treatment in the Young Boost

other studies.15,16,17 Fortunately, the largest absolute benefit Trial14 compared with only 30% in our trial. The high

of the boost dose occurred in younger patients. number of second surgeries might also relate to the higher

A similar effect of a boost dose has been reported in local recurrence rate—it was higher than the number of

some other trials, including that by Romestaing and second surgeries usually achieved presently, especially

considering that a margin greater than 1 cm was used. The

Panel: Research in context use of image-guided surgery has reduced the proportion of

re-excisions to less than 10%,21 and might also improve

Systematic review local control. The boost dose did not cause a significant

This trial was designed shortly after a few randomised trials were published,10–12 all showing increase in cardiac mortality, second primary tumours, or

equal survival after breast-conserving treatment or mastectomy,13 the latter being the contralateral breast cancer (appendix). However, it did

standard treatment for early breast cancer at the time. Uncertainty existed with regard to the harm the cosmetic results and increased fibrosis,22,23

required radiation dose, leading to the question: is a radiation dose equivalent to 50 Gy in although the boost did not significantly increase severe

5 weeks targeted at the whole breast sufficient, or is an extra radiation dose to the tumour fibrosis in patients younger than 40 years, who benefited

bed needed? A search of published work showed that no extra radiation or radiation doses most from the boost. Fibrosis could also be reduced by

between 10 Gy and 25 Gy to the tumour bed were given after whole-breast irradiation. As a lowering the total dose of whole-breast irradiation, or

result of this paradox, a randomised trial was initiated to investigate the possibility of using techniques such as simultaneously integrated boost

reducing the high radiation dose used in the previous EORTC 10801 trial.13 To obtain better or intensity-modulated radiation treatment.24–27 Because

cosmetic results and less fibrosis without exceeding a difference of 5% in local control, an the size of the absolute benefit for tumour control

extra radiation dose was omitted. Later, the trial was extended to investigate the effect of decreases with increasing age, the gain in local control in

differences in local control on survival. older patients needs to be weighed against the increase in

Interpretation risk of fibrosis associated with a boost dose using

Our long-term follow-up findings show that an extra radiation dose to the tumour bed led nomograms.22,28 (Neo)-adjuvant systemic treatment

to better local control after breast-conserving treatment and therefore fewer salvage significantly reduces ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence,

mastectomies. Although the relative benefit of a boost dose was similar in all age groups, the restricting the need for a boost dose. The development of

absolute gain of a boost dose was largest in patients younger than 51 years. However, better gene or protein profiles that predict radiosensitivity might

local control coincided with more fibrosis, and cosmetic results were somewhat worse. To help to select patients for radiation and the dose to use.29,30

decide the proper radiation dose for an individual patient, one should therefore take into A treatment boost reduced the number of salvage

account the age of the patient. One should also consider the more local control reported in mastectomies for initial local recurrence by more than a

more recent trials, probably as a result of better screening, image-guided surgery and third compared with the no boost group. The choice of a

radiotherapy, and more use of adjuvant systemic treatment.14 In patients older than 60 years, salvage treatment is related to the type of relapse—eg,

the gain in local control from a boost dose is small; therefore, it should only be given to systemic treatment is used instead of mastectomy for

patients with microscopically incomplete excision, especially because survival was not diffuse ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence or local

improved in our study. recurrences that occur in combination with distant spread

of disease.

54 www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015

Articles

Our study has several limitations. Central pathology 6 Poortmans PM, Collette L, Horiot JC, et al. Radiation Oncology and

review was done for only a third of patients, although a Breast Cancer Groups. Impact of the boost dose of 10 Gy versus 26 Gy

in patients with early stage breast cancer after a microscopically

serious discrepancy between the original pathology incomplete lumpectomy: 10-year results of the randomised EORTC

report and the review occurred in only a few patients.31 boost trial. Radiother Oncol 2009; 90: 80–85.

Ductal carcinoma in situ reaching the inked margin of 7 International Commission of Radiation Units and Measurements:

Dose specification for reporting external beam therapy with photons

the surgical specimen was not recorded. However, for and electrons: report 50. Bethesda: ICRU, 1992.

1616 patients, the 10-year cumulative risk of local breast 8 Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time

cancer relapse as a first event was not significantly data. 2nd edn. Hoboken: John Wiley, 2002.

9 Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the

affected if the margin was scored negative, close, or subdistribution of competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496–509.

positive for invasive tumour or ductal carcinoma in situ 10 Fisher B, Bauer M, Margolese R, et al. Five year results of a

according to central pathology review.32 Also, clinical randomized trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental

practice guideline recommendations of the Society of mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast

cancer. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 665–73.

Surgical Oncology and the American Society for 11 Veronesi U, Delvecchio H, Greco MA, et al. Results of

Radiation Oncology were generally followed, such as quadrantectomy, axillary dissection and radiotherapy (QUART) in

repeated mammography or radiography of the specimen, T1N0 patients. In: Harris JR, Hellman S, Silen W, eds. Conservative

management of breast cancer. New surgical and radiotherapeutic

advised in case of preoperative microcalcifications.32 The techniques. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company, 1983: 91–101.

whole-breast irradiation dose of 50 Gy in 5 weeks is 12 Sarrazin D, Le M, Fontaine MF, Arriagada R. Conservative treatment

different from the shorter fractionation schedules in the versus mastectomy in or small T2 breast cancer - a randomized

clinical trial. In: Harris JR, Hellman S, Silen W, eds. Conservative

START trial.33 However, because local control and side- management of breast cancer. New surgical and radiotherapeutic

effects were not substantially different in the START techniques. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company, 1983: 101–11.

trial, one might expect that the effect of the boost dose is 13 Litière S, Werutsky G, Fentiman IS, et al. Breast conserving therapy

versus mastectomy for stage I-II breast cancer: 20 year follow-up of

similar in patients treated with shorter fractionation the EORTC 10801 phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;

schedules.33 Fibrosis is difficult to measure objectively, 13: 412–19.

although cosmetic outcome can be measured more 14 Bartelink H, Bourgier C, Elkhuizen P. Has partial breast irradiation

by IORT or brachytherapy been prematurely introduced into the

objectively.34 Finally, the effect of a boost dose seems to be clinic? Radiother Oncol 2012; 104: 139–42.

independent of tumour characteristics such as grade and 15 Elkhuizen P, Van de Vijver MJ, Hermans JO, et al. Local recurrence

stage, but also of giving adjuvant systemic treatment, as after breast-conserving therapy for invasive breast cancer: high

incidence in young patients and association with poor survival.

reported previously.2 Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998; 40: 859–67.

Contributors 16 Vrieling C, Fourquet A, Hoogenraad WJ, et al; on behalf of the

HB and J-CH designed the study. HB, PM, PP, CW, AF, JJ, DS, BO, CR, EORTC Radiotherapy, Breast Cancer Groups: Can patient-,

J-CH, HS, EVL, YK, PE, RB, RM, DM, J-BD, VR, and ROM collected data. treatment- and pathology-related characteristics explain the high local

LC and SC analysed data. HB, LC, PM, PP, CW, AF, JJ, DS, BO, CR, recurrence rate following breast-conserving therapy in young

J-CH, HS, EVL, YK, PE, RB, RM, DM, J-BD, VR, R-OM, and SC patients? Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 932–44.

interpreted data and wrote the first draft. All authors approved the report. 17 Bollet MA, Sigal-Zafrani B, Mazeau V, et al. Age remains the first

prognostic factor for loco-regional breast cancer recurrence in young

Acknowledgments women treated with breast conserving surgery first. Radiother Oncol

Both Rolf-Peter Müller and Emile Salamon helped to gathering patient 2007; 82: 272–80.

data but have since died. Their work was continued by Rudolf Bongartz 18 Polgar C, Fodor J, Orosz Z, et al. Electron and high-dose-rate

and Vincent Remouchamps, respectively. Emmanuel van der Schueren brachytherapy boost in the conservative treatment of stage I–II breast

was essential to the design of the study but has also since died. This cancer: first results of the randomized Budapest boost trial.

study was funded by Fonds Cancer, Belgium. We thank the patients who Strahlenther Onkol 2002; 178: 615–23.

participated in the study and all the doctors, nurses, and data managers 19 Veronesi U, Orecchia R, Maisonneuve P, et al. Intraoperative

involved in the trial (appendix). radiotherapy versus external radiotherapy for early breast cancer

(ELIOT): a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet Oncol

Declaration of interests 2013; 14: 1269–77.

We declared no competing interests. 20 Vaidya JS, Wenz F, Bulsara M, et al. Risk-adapted targeted

References intraoperative radiotherapy versus whole-breast radiotherapy for

1 Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effect of breast cancer: 5-year results for local control and overall survival from

radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and the TARGIT-A randomised trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 603–13.

15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data 21 Van Riet YE, Jansen FH, van Beek M, et al. Localization of

for 10 801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378: 1707–16. non-palpable breast cancer using a radiolabelled titanium seed.

2 Bartelink H, Horiot JC, Poortmans P, et al. Recurrence rates after Br J Surg 2010; 97: 1240–45.

treatment of breast cancer with standard radiotherapy with or without 22 Collette S, Collette L, Budiharto T, et al. Predictors of the risk of

additional radiation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1378–87. fibrosis at 10 years after breast conserving therapy for early breast

3 Bartelink H, Horiot JC, Poortmans PM, et al. Impact of a higher cancer a study based on the EORTC trial 22881-10882 ‘boost versus no

radiation dose on local control and survival in breast-conserving boost’. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 2587–99.

therapy of early breast cancer: 10-year results of the randomized boost 23 Vrieling C, Collette L, Fourquet A, et al. The influence of patient,

versus no boost EORTC 22881-10882 trial. J Clin Oncol 2007; tumor and treatment factors on the cosmetic results after

25: 3259–65. Radiotherapy and Breast Cancer Cooperative Groups. Radiother Oncol

4 Romestaing P, Lehingue Y, Carrie C, et al. Role of a 10-Gy boost in the 2000; 55: 219–32.

conservative treatment of early breast cancer: results of a randomized 24 Hau E, Browne LH, Khanna S, et al. Radiotherapy breast boost with

clinical trial in Lyon, France. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 963–68. reduced whole-breast dose is associated with improved cosmesis: the

5 Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing results of a comprehensive assessment from the St. George and

for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics 1975; Wollongong randomized breast boost trial.

31: 103–15. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82: 682–89.

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015 55

Articles

25 Mukesh MBI, Barnett GC, Wilkinson JS, et al. Randomized controlled 31 Jones HA, Antonini N, Hart AA, et al. Impact of pathological

trial of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for early breast cancer: characteristics on local relapse after breast-conserving therapy:

5-year results confirm superior overall cosmesis. J Clin Oncol 2013; a subgroup analysis of the EORTC boost versus no boost trial.

31: 4488–95. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4939–47.

26 Hau E, Browne L, Capp A, et al. The impact of breast cosmetic and 32 Buchholz TA, Somerfield MR, Griggs JJ, et al. Margins for

functional outcomes on quality of life: long-term results from the St. breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stage I and

George and Wollongong randomized breast boost trial. II invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology

Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 139: 115–23. endorsement of the Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society

27 Van Parijs H, Miedema G, Vinh-Hung V, et al. Short course for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol 2014;

radiotherapy with simultaneous integrated boost for stage I-II breast 32: 1502–06.

cancer, early toxicity of a randomized clinical trial. Radiat Oncol 33 Haviland JS, Owen JR, Dewar JA, et al. The UK Standardisation

2012; 7: 80. of Breast Radiotherapy (START) trials of radiotherapy

28 Van Werkhoven E, Hart G, Van Tinteren H, et al. Nomogram to hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: 10-year

predict ipsilateral breast relapse based on pathology review from the follow-up results of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol

EORTC 22881-10882 boost versus no boost trial. Radiother Oncol 2011; 2013; 14: 1086–94.

100: 101–07. 34 Immink JM, Putter H, Bartelink H, et al. Long-term cosmetic

29 Torres-Roca JF, Eschrich S, Zhao H, et al. Prediction of radiation changes after breast-conserving treatment of patients with stage I–II

sensitivity using a gene expression classifier. Cancer Res 2005; breast cancer and included in the EORTC ‘boost versus no boost’ trial.

65: 7169–76. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 2591–98.

30 Servant N, Bollet MA, Halfwerk H, et al. Search for a gene expression

signature of breast cancer local recurrence in young women.

Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 1704–15.

56 www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 16 January 2015

You might also like

- Articles: BackgroundDocument9 pagesArticles: Backgroundalchemistbro 007No ratings yet

- jco.2007.11.4991Document7 pagesjco.2007.11.4991brasilianaraNo ratings yet

- Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Plus Surgery Versus Surgery Alone For Oesophageal or Junctional Cancer (CROSS) Long-Term Results of A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesNeoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Plus Surgery Versus Surgery Alone For Oesophageal or Junctional Cancer (CROSS) Long-Term Results of A Randomised Controlled TrialSergioNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument13 pagesArticles: BackgroundAli FarhanNo ratings yet

- Predictors of the risk of fibrosis at 10 years after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer – A study based on the EORTC trial 22881–10882 ‘boost versus no boost’ / European Journal of Cancer Collette, 2008Document13 pagesPredictors of the risk of fibrosis at 10 years after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer – A study based on the EORTC trial 22881–10882 ‘boost versus no boost’ / European Journal of Cancer Collette, 2008saipraveen03No ratings yet

- Original Research: Gynecological CancerDocument7 pagesOriginal Research: Gynecological CancerMetharisaNo ratings yet

- Pathologic Response When Increased by Longer Interva - 2016 - International JouDocument10 pagesPathologic Response When Increased by Longer Interva - 2016 - International Jouwilliam tandeasNo ratings yet

- Internal Mammary Node Irradiation in Breast Cancer: The Issue of Patient SelectionDocument3 pagesInternal Mammary Node Irradiation in Breast Cancer: The Issue of Patient SelectionmarrajoanaNo ratings yet

- 27 10 Year Survival After Breast-Conserving Surgery Plus Radiotherapy Compared With Mastectomy in Early Breast Cancer in The Netherlands - A Population-Based StudyDocument13 pages27 10 Year Survival After Breast-Conserving Surgery Plus Radiotherapy Compared With Mastectomy in Early Breast Cancer in The Netherlands - A Population-Based StudyAnonymous 34158U5pNo ratings yet

- Radioterapia Tumor PhyllodesDocument5 pagesRadioterapia Tumor Phyllodesmanuel barrientosNo ratings yet

- Article - Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal Cancer (COLOR II) - Short-Term Outcomes of A Randomised, Phase 3 Trial - 2013Document9 pagesArticle - Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal Cancer (COLOR II) - Short-Term Outcomes of A Randomised, Phase 3 Trial - 2013Trí Cương NguyễnNo ratings yet

- strassDocument12 pagesstrasssaenzladinoNo ratings yet

- Eortc 22911 PDFDocument10 pagesEortc 22911 PDFAndres Felipe Cordoba AriasNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument11 pagesArticles: BackgroundOncología CdsNo ratings yet

- ijgc-2020-001996Document8 pagesijgc-2020-001996Sulaeman Andrianto SusiloNo ratings yet

- Regional Nodal Irradiation in Early-Stage Breast CancerDocument10 pagesRegional Nodal Irradiation in Early-Stage Breast Canceryingming zhuNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 0908806Document11 pagesNej Mo A 0908806dimazerrorNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerDocument9 pagesA Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic Versus Open Surgery For Rectal CancerFarizka Dwinda HNo ratings yet

- Rectal Cancer: International Perspectives on Multimodality ManagementFrom EverandRectal Cancer: International Perspectives on Multimodality ManagementBrian G. CzitoNo ratings yet

- Kehoe 2015Document9 pagesKehoe 2015Juanda RaynaldiNo ratings yet

- Local Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Surgery and RadiotherapyDocument6 pagesLocal Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Surgery and RadiotherapyLizeth Rios ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Nica 2020Document7 pagesNica 2020Hari NugrohoNo ratings yet

- FLOT 3 QuimioterapiaDocument8 pagesFLOT 3 Quimioterapiaerica corral corralNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Romanian SeriesDocument5 pagesAbdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Romanian SeriesPanuta AndrianNo ratings yet

- Special ArticleDocument21 pagesSpecial ArticleAhana MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Kapiteijn 2001Document9 pagesKapiteijn 2001cusom34No ratings yet

- PIIS014067361261900XDocument10 pagesPIIS014067361261900X呂鍇東No ratings yet

- s13014 015 0495 4Document6 pagess13014 015 0495 4produxing 101No ratings yet

- Eortc 22911Document7 pagesEortc 22911yingming zhuNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Treatment of Colorectal Cancer: Staging – Treatment – Pathology – PalliationFrom EverandMultidisciplinary Treatment of Colorectal Cancer: Staging – Treatment – Pathology – PalliationGunnar BaatrupNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1879850016300947Document7 pagesPi Is 1879850016300947Daniela GordeaNo ratings yet

- Schöffski Et Al. - 2016 - Eribulin Versus Dacarbazine in Previously TreatedDocument9 pagesSchöffski Et Al. - 2016 - Eribulin Versus Dacarbazine in Previously TreatedM.No ratings yet

- Abdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceDocument8 pagesAbdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceWitrisyah PutriNo ratings yet

- Ovarian CancerDocument7 pagesOvarian CancerAndi AliNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 2005 - Kirova - Radiation Induced Sarcomas After Radiotherapy For Breast CarcinomaDocument8 pagesCancer - 2005 - Kirova - Radiation Induced Sarcomas After Radiotherapy For Breast CarcinomaRizki Amalia JuwitaNo ratings yet

- Esofago Carvical Valmasoni 2018Document9 pagesEsofago Carvical Valmasoni 2018Carlos N. Rojas PuyolNo ratings yet

- CommentaryDocument3 pagesCommentaryGodha KiranaNo ratings yet

- Achy 2017 01 005Document8 pagesAchy 2017 01 005Head RadiotherapyNo ratings yet

- Radiotherapy and OncologyDocument8 pagesRadiotherapy and OncologyFarah SukmanaNo ratings yet

- Wo2019 PosterDocument1 pageWo2019 PosterCx Tx HRTNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic-Assisted Radical Vaginal Hysterectomy (LARVH) : Prospective Evaluation of 200 Patients With Cervical CancerDocument7 pagesLaparoscopic-Assisted Radical Vaginal Hysterectomy (LARVH) : Prospective Evaluation of 200 Patients With Cervical CancerHari NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Rosendahl 2017Document7 pagesRosendahl 2017Prince VallejosNo ratings yet

- Medi 95 E4797Document5 pagesMedi 95 E4797tika apriliaNo ratings yet

- Endometrial Cancer - Reduce To The Minimum. Anew Paradigm For Adjuvant Treatments?Document6 pagesEndometrial Cancer - Reduce To The Minimum. Anew Paradigm For Adjuvant Treatments?najmulNo ratings yet

- Abdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceDocument8 pagesAbdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceWitrisyah PutriNo ratings yet

- BreastCare - 2015 10320 324Document5 pagesBreastCare - 2015 10320 324Rohit MaldeNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Philippe Morice, Alexandra Leary, Carien Creutzberg, Nadeem Abu-Rustum, Emile DaraiDocument15 pagesSeminar: Philippe Morice, Alexandra Leary, Carien Creutzberg, Nadeem Abu-Rustum, Emile DaraiGd SuarantaNo ratings yet

- Local Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Surgery and RadiotherapyDocument6 pagesLocal Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Surgery and RadiotherapyLizeth Rios ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Wagner1994 (No Hace Biopsia)Document7 pagesWagner1994 (No Hace Biopsia)ouf81No ratings yet

- Whelan Et Al 2000 CancerDocument7 pagesWhelan Et Al 2000 Cancerkrishna shafiraNo ratings yet

- QUAD. 0 7 21 RegimenDocument6 pagesQUAD. 0 7 21 RegimenEskadmas BelayNo ratings yet

- Irradiação Eletiva MI, JAMA, 2021Document10 pagesIrradiação Eletiva MI, JAMA, 2021Flavio GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy: Case ReportDocument5 pagesGynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy: Case ReportMetharisaNo ratings yet

- Oncological outcomes of fertility-sparing surgery for early-stage cervical cancerDocument14 pagesOncological outcomes of fertility-sparing surgery for early-stage cervical cancerKaleb Rudy HartawanNo ratings yet

- ESGO Cervical-Cancer A6 PDFDocument48 pagesESGO Cervical-Cancer A6 PDFRocking ChairNo ratings yet

- EAU Guidelines Update on Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder CancerDocument15 pagesEAU Guidelines Update on Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder CancerMuhammad FaisalNo ratings yet

- Residual Breast Tissue After Mastectomy, How Often and Where It Is LocatedDocument11 pagesResidual Breast Tissue After Mastectomy, How Often and Where It Is LocatedBunga Tri AmandaNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Dose Is Associated With Toxicity in Image Guided Tandem Ring or Ovoid-Based BrachytherapyDocument7 pagesVaginal Dose Is Associated With Toxicity in Image Guided Tandem Ring or Ovoid-Based BrachytherapyFlor ZalazarNo ratings yet

- The Future of External Beam Irradiation As Initial Treatment of Rectal CancerDocument6 pagesThe Future of External Beam Irradiation As Initial Treatment of Rectal CancerMaxime PorcoNo ratings yet

- UpdateDocument2 pagesUpdate980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Cahan 2015Document2 pagesCahan 2015980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- JAMA 2011 Giuliano 569 75Document7 pagesJAMA 2011 Giuliano 569 75Fran CordobaNo ratings yet

- Interstitial High-Dose-Rate Gynecologic Brachytherapy: Clinical Workflow Experience From Three Academic InstitutionsDocument10 pagesInterstitial High-Dose-Rate Gynecologic Brachytherapy: Clinical Workflow Experience From Three Academic Institutions980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- RadBio StudyGuide 20Document164 pagesRadBio StudyGuide 20princess ybanezNo ratings yet

- Achy 2020 08 007Document10 pagesAchy 2020 08 007980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Achy 2016 02 008Document7 pagesAchy 2016 02 008980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- J Semradonc 2019 08 010Document13 pagesJ Semradonc 2019 08 010980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Cronograma Actividades Academicas Septiembre 2021Document5 pagesCronograma Actividades Academicas Septiembre 2021980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- MRI en RadioterapiaDocument19 pagesMRI en Radioterapia980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Seram2012 S-0117Document25 pagesSeram2012 S-0117980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Theroleofradiation Therapyforpancreatic Cancerintheadjuvantand NeoadjuvantsettingsDocument23 pagesTheroleofradiation Therapyforpancreatic Cancerintheadjuvantand Neoadjuvantsettings980Denis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris AskepDocument4 pagesBahasa Inggris AskepMona Indah100% (2)

- Mechanical VentilationDocument108 pagesMechanical Ventilationrizal aljufri100% (1)

- Drug Study Amoxicillin PDFDocument4 pagesDrug Study Amoxicillin PDFMc SantosNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Clinical Study On The Effect of Kottamchukkadi and Kolakulathadi Upanaha Sweda in JanusandhigatavataDocument6 pagesA Comparative Clinical Study On The Effect of Kottamchukkadi and Kolakulathadi Upanaha Sweda in JanusandhigatavataInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- UTP Field Trip ReportDocument8 pagesUTP Field Trip Reportdcros88No ratings yet

- GPST Stage 2Document34 pagesGPST Stage 2Chiranjeevi Kumar EndukuruNo ratings yet

- KNH 413 Case Study 1Document9 pagesKNH 413 Case Study 1api-272540385No ratings yet

- InfertilityDocument10 pagesInfertilityHarish Labana100% (1)

- Autism Fact Sheet EnglishDocument1 pageAutism Fact Sheet Englishapi-332835661No ratings yet

- Sustained Release Formulation Design and ComponentsDocument46 pagesSustained Release Formulation Design and ComponentsMehak LubanaNo ratings yet

- Gender Affirmation - 2 - 815961108 PDFDocument318 pagesGender Affirmation - 2 - 815961108 PDFAlex Rolando SuntaxiNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect PDFDocument2 pagesPresent Perfect PDFInma Polo TengoganasdefiestaNo ratings yet

- Resident's Page: Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's LampDocument5 pagesResident's Page: Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's Lamp Wood's LampMovaliya GhanshyamNo ratings yet

- NutriDocument2 pagesNutriumer sheikhNo ratings yet

- BIOS LIFE - Diabetes in Control Study #2 by Steven Freed and David JoffeDocument1 pageBIOS LIFE - Diabetes in Control Study #2 by Steven Freed and David JoffeHisWellnessNo ratings yet

- Bio12 c10 10 7Document8 pagesBio12 c10 10 7Eric McMullenNo ratings yet

- Management of Riga Fede Disease A Case ReportDocument3 pagesManagement of Riga Fede Disease A Case ReportkerminkNo ratings yet

- NephrolithiasisDocument2 pagesNephrolithiasisMichalaNo ratings yet

- 2010-2011 Uwc Maastricht Welcome GuideDocument27 pages2010-2011 Uwc Maastricht Welcome Guidegap09No ratings yet

- Biscuits For Breakfast: Empty Calories For The Hungry Poor by Maheen MirzaDocument5 pagesBiscuits For Breakfast: Empty Calories For The Hungry Poor by Maheen MirzaSubhadeep GhoshNo ratings yet

- ExtenderDocument3 pagesExtenderMichele RogersNo ratings yet

- Acne Fulminans Explosive Systemic Form of Acne PDFDocument8 pagesAcne Fulminans Explosive Systemic Form of Acne PDFPaulus SidhartaNo ratings yet

- Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)Document3 pagesPerceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)Amal B Chandran0% (1)

- Soumya Mary 1 Year MSC (N)Document24 pagesSoumya Mary 1 Year MSC (N)Salman HabeebNo ratings yet

- Substance AbuseDocument8 pagesSubstance Abuseapi-19780865No ratings yet

- Trisomy 21-Down SyndromeDocument1 pageTrisomy 21-Down Syndromeapi-253727022No ratings yet

- EWMA Lower Leg Ulcer Diagnosis SuppDocument76 pagesEWMA Lower Leg Ulcer Diagnosis SuppAna CayumilNo ratings yet

- Ahara GeriatricsDocument10 pagesAhara GeriatricsSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- Cleaner production assessment at Carm Foods EnterprisesDocument62 pagesCleaner production assessment at Carm Foods EnterprisesHarry EdnacotNo ratings yet

- We Get Results!: BarreDocument36 pagesWe Get Results!: BarreCoolerAdsNo ratings yet