Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kennedy OverviewProgressiveEra 1975

Kennedy OverviewProgressiveEra 1975

Uploaded by

sondes.boughallebOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kennedy OverviewProgressiveEra 1975

Kennedy OverviewProgressiveEra 1975

Uploaded by

sondes.boughallebCopyright:

Available Formats

Overview: The Progressive Era

Author(s): David M. Kennedy

Source: The Historian , MAY, 1975, Vol. 37, No. 3 (MAY, 1975), pp. 453-468

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24444043

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Historian

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview: The Progressive Era

By

David M. Kennedy*

//> ■ ^ he term 'progressive movement' has been so wide

** I used, so much discussed, and so differently interpret

I that any exposition of its meaning and principles, to

be adequate, must be prefaced by careful definition."

With those words in 1915, Benjamin Parke DeWitt opened t

first comprehensive discussion of progressivism, The Progressi

Movement. He wrote, he explained, in order "to give form an

definiteness to a movement which is, in the minds of man

confused and chaotic."1 Time has not been kind to DeWitt's

ambitious effort to dispel that chaos. His own contemporaries

may have been willing to agree with his basically flattering image

of them, but later observers have increasingly disagreed, not only

with DeWitt, but among themselves, about the character and

meaning of progressivism. Especially after the publication of

Richard Hofstadter's Age of Reform in 1955, the babble of dis

agreement rose to a discordant crescendo, so intense and distracting

that at least one of our colleagues has urged quiet interment as

the only way to restore order. In "An Obituary for the Progressive

Movement," Peter Filene, surveying the confusion about progres

sivism that nearly sixty years of scholarship have wrought, argues

that all the shouting has been about nothing after all. " 'The

progressive movement,' " he concludes, "never existed."2

The persistence of disagreement about progressivism from

DeWitt right down to our own time should humble all who still

wish to say something meaningful about the matter, or even to

continue to use the term. But the term, at least, seems fixed in

our lexicon, and despite Filene's funereal rites, most scholars

continue to assume the reality and importance of the subject.

Given the multiplicity and the tenacity of the attempts "to give

form and definiteness" to the progressive movement, perhaps an

overview can best begin with a review of those attempts at a general

statement that have been made in the past.

• The author is Associate Professor of History at Stanford University, Stanford,

California.

1 Benjamin Parke DeWitt, The Progressive Movement (Seattle, 1968; first

published 1915), 3, viii.

2 Peter G. Filene, "An Obituary for the Progressive Movement," American

Quarterly, XX (1970), 20-34.

453

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

According to DeWitt, progressivism embraced three broad

goals which had been on the American political agenda for

twenty-five years by the time he was writing and which by the

appeared to him to be substantially accomplished: the remov

of corruption from public life, the enlargement of popular part

cipation in government, and the "conviction that the functions

of government at present are too restricted and that they must be

increased and extended to relieve social and economic distress."8

Historians ever since have been broadly in accord that those

objectives constituted a progressive program, though they have

given more attention to some parts of it than to others.

In equally broad terms, it can be argued that the interpretation

of progressivism has gone through five major phases, which have

roughly followed (though not necessarily supplanted) one another.

Those five major interpretive modes might be called, respectively,

the "progressive," the "consensual," the "new left," the "organi

zational," and the "neo-progressive" — all terms which, when

applied to specific authors, need some refinement. In a general

way, however, they do describe at least some recognizable patterns

in the three generations of scholarship on progressivism.

It is no mere coincidence, of course, that the first of the modes

just cited bears the same name as the object of study itself:

progressive. As John Higham has remarked, "the crucial fact"

that explains the distinctiveness of that powerfully influential

school of historians who came to maturity in the early part of this

century "was a broad sympathy with the spirit of reform then

developing in contemporary life."4 For DeWitt and his cohorts,

such as Charles Beard and V. L. Parrington, their conception of

their own political roles dictated their view of American history

in general, and especially of their own era: to them, progressivism

was just another battle, albeit a major one, between the forces of

democracy and the forces of privilege. Since the course of all

history, or at least all American history, could be explained as a

kind of Hegelian elaboration of the principle of democracy, the

outcome of that battle was never really in doubt.

The progressive view of history has been an extremely

appealing one: it embodies moral passion, has its own built-in

dramatic elements in the clash between the "people" and the

"interests," and contains also its own dynamic principle, which

makes it so adaptable to the narrative form that has for so long

' DeWitt, The Progressive Movement, 5.

•John Higham, History: The Development of Historical Studies in the United

States (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1965), 171.

m'i

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

characterized historical discourse. This compatibility of the

progressive view with the dominant American democratic myth,

and with the narrative form, has produced some monuments of

American historical scholarship and has made it a durable and

still compelling approach in the teaching and writing of our

history. But it is not a position without its liabilities. In the

case of the early twentieth century, its chief deficiencies have been

four: by postulating that history was made to move by a process

of cyclical confrontation between the people and the interests, the

progressive historians never bothered to inquire too rigorously

about the identity of reformers or about the timing of reform.

Moreover, given the general progressive eschatology, few serious

questions were raised about the purposes or the results of reform;

it was simply assumed to have been democratic in intention and

to have been largely successful. Its successes were further assumed

to have given the rest of the twentieth century its dominant

characteristics.

Richard Hofstadter, in The Age of Reform, launched a massive,

complex, and subtle assault on the progressive interpretation,

aiming especially at the questions of identity, timing, motive, and

outcome that the older generation had substantially ignored. His

has been called a "consensual" view, because Hofstadter, with so

many of his colleagues in the 1950s, approached the American past

with a skeptical attitude toward the older faith that history pro

gressed toward the realization of a democratic ideal through a cycle

of conflicts along economic lines. He acknowledged his own debt to

the progressive historians, most notably in taking, as they had,

reform itself as his unit of analysis. ("The surge of reform," he

wrote, "has set the tone of American politics for the greater part

of the twentieth century."5) But Hofstadter suspected (and often

regretted) the durability of certain features of American political

culture. Much of his work emphasized the persistent and perennial

factors, such as an abiding, common commitment to capitalism,

which gave coherence and unity to the American experience, rather

than the sharp divisions that the progressives had seen as constantly

generating its transformation. This emphasis was particularly

apparent in his second book, The American Political Tradition.

When he then came to examine progressivism, where division

appeared, at least, to be authentic, it led him to ask some troubling

questions. He questioned especially the assumptions about the

sources, inevitability, and results of reform that had inhered in

the older analysis. Who, he asked, were the progressives? Why

s Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (New York, 1955), 3.

4iji>

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

did they undertake reform at just this time? And what were th

results of their efforts?

To all of those questions Hofstadter gave answers of great

originality and persuasiveness. It would not be too much to say

that The Age of Reform was the single most influential book ever

published on the history of modern reform. Certainly it did more

than any other to undermine the older progressive analysis. But

it would be a mistake to conclude too quickly that Hofstadter

buried that analysis once and for all.

Hofstadter brought the most originality, perhaps, to his dis

cussion of progressive identity. Here he began with the work of

George Mowry and Alfred D. Chandler, who had shown that the

reformers in California and in the national Progressive party, at

any rate, were economically successful, predominantly urban,

middle-class persons. That fact by itself did much to qualify the

orthodox view that reform was a continuous tradition, always

carried forward by the underprivileged and disadvantaged. Hof

stadter immediately saw that Mowry's and Chandler's findings

distinguished progressivism from populism, with which the

traditional literature had usually identified it. But Hofstadter

drew a still more interesting implication when he noted that the

progressive era, unlike the populist era, had been marked by

general prosperity. "This fact," he wrote, "is a challenge to the

historian. Why did the middle classes undergo this remarkable

awakening at all, and why during this period of general prosperity

in which most of them seem to have shared? What was the place

of economic discontents in the Progressive movement? To what

extent did reform originate in other considerations?" Hofstadter's

answer is by now famous:

It is my thesis that [Progressive leaders], who might be

designated broadly as the Mugwump type, were Progressives

not because of economic deprivations but primarily because

they were victims of an upheaval in status that took place in

the United States during the closing decades of the nineteenth

and the early years of the twentieth century. Progressivism,

in short, was to a very considerable extent led by men who

suffered from the events of their time not through a shrinkage

in their means but through the changed pattern in the dis

tribution of deference and power.6

Several things about this passage, and about Hofstadter's

general argument, deserve comment. First, by distinguishing

populism from progressivism, Hofstadter implicitly suggested the

discontinuous character of the reform impulse. This, in turn, led

'Ibid., 135.

456

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

to two other considerations, the latter of which he made explicit

in his concluding pages: that the period around 1900 seemed to

mark a significant break with the past, the beginning of a "modern"

era, and that the New Deal represented the full fruition of the

modern reform tradition, the culmination of a process in which

the progressive period had been only a transistory, and even

contradictory, phase. Further, the notorious "status anxiety"

thesis, which Hofstadter applied only to progressive leadership,

pushed the question of identity and motivation of that leadership

to the center of critical attention and shifted the axis of inquiry

from an economic to a psychological plane. Among the important

findings to which this emphasis on the subjective sources of reform

led Hofstadter were the discovery of a "dark side" of progressivism,

especially manifest in nativism and a penchant for moral absolut

ism, and the conclusion that much progressive economic reform

had been hesitant, ambiguous, and far less effective than an older

view had had it. A persistent atavism, a hankering for an older,

more certain, but, in Hofstadter's judgment, obsolescent economic

order in which individual moral character could be tested, disposed

the progressives to seek "ceremonial solutions" to stubborn

economic problems that, presumably, a more economically self

interested and clear-sighted group would have resolved more

decisively. Though he did recognize that progressive reform had

provided valuable service in taming "industrial barbarism" and

in throwing "big business and the vested interests on the

defensive," Hofstadter nevertheless had opened the door to the

possibility that the progressive movement was not "progressive"

or "liberal" at all in the accepted sense of those terms.7

All of this went a long way toward eroding the older pro

gressive interpretation, but one should not overlook the extent

to which Hofstadter remained within the gross perimeter of the

progressive framework. Most significantly, Hofstadter took as his

subject the ancient progressive one: reform itself. He assumed,

as had his forebears, that the reform tradition, whatever its precise

character might be, was the dominant motif of twentieth-century

American political life. He even gave qualified agreement to the

proposition that "the insistence that the power of law be brought

to bear against [industrial abuses] is among our finest inheritances

from the Progressive movement."8 Hofstadter never really aban

doned, in other words, the notion that a fight, or at least the

elements of a fight, between "reform" and business had much to

do with the essence of progressivism.

■•Ibid., 242, 254.

8 Ibid., 242.

457

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

If Hofstadter severely modified the progressive historiograph

ical framework while still remaining partly within it, the "new

left" view appeared to accept that framework while turning it

squarely on its head. The term "new left" has been much abused,

but writers of this persuasion (such as Gabriel Kolko and James

Weinstein) make in common a harshly critical appraisal of pro

gressivism as "the triumph of conservatism." On this view, the

reality of conflict, or at least potential conflict, between th

"people" and the "interests" is again affirmed, though usually only

implicitly, a presence waiting in the wings as it were, as the drama

of extending corporate control dominates the center of the stage

There should have been such a conflict, in other words, but the

people had no champions (one must make an exception of

Weinstein here, who finds a viable "anticorporation Left" in the

Socialist Party). The progressives — Kolko focusses particularly on

Theodore Roosevelt — were conservatives all along, interested only

in preserving the existing distribution of wealth and power. Pro

gressivism really amounted, Kolko tells us, to "political capitalism,"

the purposive and successful attempt by the largest and mos

powerful business interests to use the federal government to

achieve a measure of stability in the economic and social order

that private efforts had failed to accomplish.

Kolko's book The Triumph of Conservatism (1963) and to a

lesser extent James Weinstein's The Corporate Ideal in the Libera

State (1968) have received stiff criticism from most historians, and

a sympathetic response from many students in the last troubled

decade. Most of the professional commentary aims to show that

Kolko first narrowed progressivism to an extraordinarinly small

compass — federal regulatory legislation — and that he exaggerated

the degree of business control over that legislation by the arbitrary

limitation of his sources and the consequent nearly complete lack

of attention to factors other than business influence.9

Moreover, critics have pointed out that Kolko really said

nothing new when he remarked the basically pro-capitalist char

acter of progressivism. Certainly the so-called "consensus"

historians of the post-World War II period had been at pains to

point out the intramural and essentially capitalist character of

almost all American political debate. Kolko acknowledged as

much when he concluded, "No socially or politically significant

group tried to articulate an alternative means of organizing indus

trial technology. . . . Such a program was never formulated in

* John Braeman, "The Square Deal in Action: A Case Study in the Growth of

'The National Police Power,'" Change and Continuity in Twentieth-Century

America (New York, 1966), 35-80, is a valuable corrective to a part of Kolko's account.

458

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

this period either in America or Europe."10 Kolko therefore, so

the argument runs, simply repeated in stronger language what

others had long been saying: that America represents an unusually

successful conservative social order, whose "reforms" have them

selves had a basically conservative thrust. But what is striking in

the reception given Kolko's book is the vehemence with which

it was attacked by other historians who accused him, in effect, of

seeing the same patterns as they in American history. Perhaps the

explanation of that vehemence is to be found in the fact that

whereas the "consensus" writers tried to explain and account for

the conservative context of American history, new left writers

have seemed to blame historical actors for the consequences of

that context without sufficiently acknowledging the context itself.

As Joseph Huthmacher put it in commenting on Kolko's work,

"One is always free to regret that America is America because she

is America. But I'm not sure that preoccupation with such regrets

is conducive to best understanding or explicating the whys and

hows of American history."11

Kolko's work, however, has not been utterly without value in

the explication of those whys and hows. He has, for one thing,

provided a powerful incentive to the examination of early

twentieth-century political economy, a subject that had languished

before the advent of radical inquiries in the 1960s. He has, in

addition, been probably the most forceful single voice in debunk

ing for twentieth-century history Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.'s cele

brated dictum that "liberalism in America has been ordinarily

the movement on the part of other sections of society to restrain

the power of the business community." As Kolko said, "Only if

we mechanistically assume that government regulation of the

economy is automatically progressive can we say that the federal

regulation of the economy during 1900 to 1916 was progressive

in the commonly understood sense of the term."12 One can, of

course, turn Kolko's statement around, and say that we can call

the government understandings or detentes with private business,

which he discusses, "conservative" in the usual sense of that term

only if we mechanistically assume that the state has no function

other than to reinforce the existing structure of economic power.

In any case, Kolko has helped more than nearly any other writer

10 Gabriel Kolko, The Triumph of Conservatism (New York, 1963), 305, 286.

u J. Joseph Huthmacher, "A Critique of the Kolko Thesis," in Otis L. Graham,

Jr., From Roosevelt to Roosevelt: American Politics and Diplomacy, 1901-1941 (New

York, 1971), 101-2.

12 Kolko, Triumph, 58.

459

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

to demythologize the concept of the state that had inhered in a

great deal of liberal historiography.

******

All the vie

least one ch

or indirectl

the newly

machine a

around the

tension wa

stadter it w

Kolko it w

articulated,

who sough

more drasti

of a persist

might mor

spheres), h

of progress

In the last

P. Hays an

transcend t

approach, a

bility betw

institution

suggested s

1957, and o

vation and

the argume

read exam

"organizat

for Order

In all of th

necessary a

nor the con

a bygone er

of a new m

experts to b

the evils —

localism. Re

the inner d

as Wiebe p

13 Samuel P.

Progressive Er

460

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

of the new middle class to fulfill its destiny through bureaucratic

means."14

The assimilation of reform to the interests of ambitious elites

who shaped new organizational techniques for the purpose of social

control has led many people to link the Hays-Wiebe approach

with that of Gabriel Kolko. To be sure, there are points of contact.

All three of these authors, for example, demonstrate the anti

democratic character of much progressive reform. But the two

analyses are clearly distinguishable. Kolko is concerned with

showing the continuity of the power of an older capitalist class

that craftily used the state to defend its social and economic

position. Hays and to an even greater extent Wiebe, on the other

hand, argue that a new class, whose power came not from inherited

wealth or status but from the possession of new tools of science,

organizational expertise, and a broad, integrative social vision,

transformed early twentieth-century American society in an

aggressive drive to extend and amplify their influence.

This distinction is an important one, and it stems from an

important debate that followed the publication of The Age of

Reform, a debate in which Hays and Wiebe were intensely inter

ested but which attracted Kolko hardly at all. The point at issue

was the identity of the progressives. In brief, the debate revolved

around the idea of status anxiety that Hofstadter had introduced

as an explanation for progressive reform. Studies in several states

showed that the biographical profile Hofstadter had drawn

of the reformers was nearly identical to that of their opponents.

Hofstadter, in short (and Chandler and Mowry before him), had

not bothered to examine a control group to test the uniqueness

of his explanatory factor. As Hays concluded: "One cannot

explain the distinctive behavior of people in terms of character

istics which are not distinctive to them."15

In rejecting the status anxiety theory, Hays and Wiebe took

the first step in what became an almost complete repudiation of

Hofstadter's account of progressivism. For Hofstadter, the pro

gressives had always displayed a certain irrationality, a troubling

inability to come to terms with the conditions of twentieth-century

life. He spoke, for example, of "the protests of reformers against

... a managerial and bureaucratic outlook." "The central theme

in Progressivism," he said elsewhere, "was this revolt against the

industrial discipline: the Progressive movement was the complaint

"Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order (New York, 1967), 166.

15 Hays, "The Politics of Reform," 158. There is a large literature on this

subject, best summarized in David P. Thelen, "Social Tensions and the Origins of

Progressivism," Journal of American History, LVX (1969), 323-41.

4b I

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

of the unorganized against the consequences of organization."16

Compare this with Hays' statement that "The Progressive Era

witnessed rapid strides toward a more centralized system and a

relative decline for a more decentralized system. This development

. . . involved a tendency for the decision making processes inherent

in science and technology to prevail over those inherent in repre

sentative government."17 Or with Wiebe's remarks that the "new

middle class" found "the specialized needs of an urban-industrial

system" a "godsend,"18 that the reformers in the states were

"generally younger men with a passion for the future,"19 and

that the distinguishing characteristic of progressivism was its

penchant for "bureaucratic means."20 Surely Hays and Wiebe

have rescued the progressives from Hofstadter's charges of nostalgia

and irrationality, but one suspects that they have done so by

turning the progressives into the very people long supposed to be

their enemies. Hofstadter had not been unaware of the existence

of a new middle class and its association with progressivism, but

he did not pursue the point, and despite some confusion in Hof

stadter's account, he clearly believed the "typical" progressive —

or at least the typical progressive leader — to be a member of a

displaced older elite, yearning for the restoration of the moral

verities of the nineteenth century.21

There was, of course, always some controversy not only over

the motivation of Hofstadter's progressives but over their repre

sentativeness as well. Hofstadter appeared rather arbitrarily, in

fact, to assume that the genuine progressives were, in a general

sense, those who embraced the positions, especially anti-trust, put

forward by Woodrow Wilson in the presidential campaign of 1912,

known broadly as "The New Freedom." One looks in vain in his

pages for any sustained recognition of regulationists like Theodore

Roosevelt and Herbert Croly and Walter Lippmann as authentic

progressives.

But the argument could be made that Hays and Wiebe have

embraced the contrary error — they have accepted as their norma

tive progressives those individuals (though individuals appear only

rarely in Wiebe's pages) who found the large corporate organization

a genial environment and worked to turn it to their own ends.

Both Hofstadter's definition and that of Wiebe and Hays

16 Hofstadter, Age of Reform, 10, 216.

17 Hays, "Politics of Reform," 169.

18 Wiebe, Search for Order, 113.

"Ibid., 177.

» Ibid., 166.

21 See, for example. The Age of Reform, 6-7, 217-20.

462

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

dismiss the reality of division among men who called themselves

progressive in the early twentieth century, and in Wiebe's case,

the argument that his progressives looked confidently to the future

and indeed charted the path to modernity is open to strong doubt

in light of Otis Graham's findings that only 40 percent of surviving

progressives supported the New Deal.

In short, the question of progressive identity, simple as it may

be to ask, is still a long way from being satisfactorily answered.

Even the substantial number of studies aimed at discrediting the

status anxiety thesis have not really begun to get at the crucial

part of that thesis: not men's objective social status, but their

subjective perception of that status. And about Hays' and Wiebe's

thesis of a new middle class made up of professionals, bureaucrats,

and experts as the normative progressives, a host of questions still

remain to be put. For one thing, most of the literature on the

nature of "professionalism" suggests its hostility to bureaucracy

and its preference for autonomy. To take one of Wiebe's most

striking examples, certainly the new organizational vitality of the

American Medical Association in the early twentieth century did

not make its members more amenable to bureaucratization in the

normal meaning of the word; if anything, the A.M.A. was designed

more to protect and encourage an old-style entrepreneurship in

what Wiebe nevertheless insists is a typically modernized profes

sion. At the very least, we need to put the Wiebe-Hays thesis to

the same kind of test to which the status anxiety thesis was

subjected: we need, in short, closer studies of the several

professions themselves, with special attention to the divisions

within professional groups. Did lawyers (or engineers) as a group,

for example, favor reform out of some compulsory, reflex response

to "the inner dynamics of professionalization?" An affirmative

answer hardly seems likely, yet the Wiebe-Hays approach tends

strongly to preclude any other response.22

Hays and Wiebe show a certain indebtedness to Hoftsadter

in their concern for the psychological and social, as distinct from

strictly economic, sources of reform, and Wiebe in particular

demonstrates his further obligation to Hofstadter in his preoccu

pation with the contingent character of progressivism, its

dependence on a particular historical moment and condition. But

on re-reading Wiebe, one begins to suspect that he has so far

transcended Hofstadter and other writers that he is not really

discussing progressivism at all. In his first book, Businessmen and

23 For the discussion in this paragraph, I am indebted to Wayne K. Hobson,

"Professionals, Progressives, and Bureaucratization: A Reassessment and Suggestions

for Further Research," Unpublished seminar paper, Stanford University. See also

Jerry Israel, ed., Building the Organizational Society (New York, 1972).

463

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

Reform, he assumed a tangible progressive movement, one char

acterized by a more or less articulate philosophy of the publi

interest, in which businessmen occasionally participated when i

suited their purposes but of which they formed no permanent,

reliable part. In the Search for Order, progressivism was so closel

identified with the general process of bureaucratization that one

wonders what distinguished it from other elements in the society

and wonders equally why Wiebe still used the traditional nomen

clature. (Ironically, Wiebe had criticized Hays on just this count

in Businessmen and Reform.)23 In a recent article, Wiebe seems

finally to have acknowledged the logical implication of his

approach:

The fundamental issue at stake in the history of the

progressive period is modernization. . . . What has happened

to the history of the progressive era, therefore, is far more than

an alteration in priorities, de-emphasizing one problem in

order to emphasize another. The cast of our picture is so

different we can no longer say it contains more of this, less

of that, in comparison with an older view. The subjects that

exercised an earlier generation of historians are being trans

formed to serve very different purposes. While the works of

these scholars provide an indispensable accumulation of infor

mation and a pattern of questions and answers no one wishes

to ignore, recent historians have tried to see all of this through

another lens, to begin again in their search for the proper

angle of historical vision. ... In sum, the current student of

the progressive years wants to know how American society was

put together and how it functioned. Behind these investiga

tions is a compelling sense that something big was abroad in

the land around 1900 . . . and it is this feeling which has

elevated modernization — the term that best captures its

essence — to the place of primacy.

We should now emphasize, he says, "major social changes that

subordinate reforms and reformers to the process of America's

modernization." With Peter Filene, he says that "we should

discard such terms as "progressive' and "progressive movement'

as imprecise and misleading."24

This certainly seems to throw out the baby with the bath

water. It purports to settle the issue of progressivism by simply

dismissing it as too complex, or subsuming it in a larger construct,

modernization, which may have considerable interest in its own

right. Wiebe seems to be declaring his own farewell to reform,

23 Robert H. Wiebe, Businessmen and Reform (Chicago, 1968), 271.

24 Robert H. Wiebe, "The Progressive Years, 1900-17," in William H. Cartwright

and Richard L. Watson, Jr., eds., The Reinterpretation of American History and

Culture (Washington, D.C., 1973), 425-32.

464

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

or at least the study of it. The result was perhaps predictable given

the welter of confusion that recent scholarship on the subject has

produced.

But not all scholars are prepared to heed Wiebe's call to ignore

petty surface conflict and concentrate instead on the deeper,

inexorable currents of modernization. Many remain convinced

that the intense political partisanship of the progressive period,

so far from being a misleading distraction, constituted instead its

distinguishing characteristic. David P. Thelen's study of Wisconsin

is a case in point. In his emphasis on conflict and the importance

of popular protest, Thelen harks back to the perspective of

progressive histriography. But there are important differences.

Thelen, for example, quite ingeniously cuts the Gordian knot of

progressive identity by giving up the search for a single, all

embracing definition of the typical progressive. Rather, he seeks

to explain what brought different people together into a progres

sive coalition, and he finds his answer in the Depression of 1893-97.

That experience touched so many lives so deeply, usually in

economic terms, that it nurtured a coalition that cut across class,

economic, religious, and ethnic barriers and was unified by a

consciousness of the common cause, or public interest, that Thelen

calls The New Citizenship.25 He leaves little doubt that in

Wisconsin, at least, progressivism was real, that it had specific,

largely economic, historical roots, that it was characterized by a

distinctive ethos, and that it accomplished concrete results.

So there is that fragment to shore against the ruins that so

many other recent scholars of progressivism have left us. Thelen

is undoubtedly right when he refuses to look for the normative

progressive and finds unity instead in a shared experience with

different implications in different cases, but an experience that

nevertheless produced, however briefly, common commitment to

something called "the public interest." There are times, history

suggests, when a diffuse sense of engagement with a larger com

munity is a more palpable reality than usual. The progressive era,

it seems, was one such time. Sheldon Hackney, for example, in

his study of Alabama, has also found the progressives in that state

possessed of a "genuine public spirit," and, as in Wisconsin, a

common consciousness of their roles as consumers was a major

factor in bringing Alabamians together in a progressive coalition.28

Ideology, in short, was important.

x David P. Thelen, The New Citizenship: Origins of Progressivism in Wisconsin,

1885-1900 (Columbia, Mo., 1972).

M Sheldon Hackney, Populism to Progressivism in Alabama (Princeton, N.J.,

1969).

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

But, as Samuel Hays has vigorously argued, one should not

confound ideology with behavior. What we need now, therefore,

are fewer studies of what progressive leadership said and more

inquiries into what they did, and what their followers did, espe

cially at the polls. We have precious few analyses of the progressive

electoral base and nothing for the progressive period that matche

the rigor and sophistication of the electoral analyses that scholars

like Paul Kleppner and Richard Jensen have given us for the late

nineteenth century. Surely the elections of 1912 and 1918, so long

focal points in discussions of progressivism, deserve some such

analysis.

We also need another kind of study of the electoral process.

The progressives themselves defined their movement as embracing

three broad goals: an end to corruption, majoritarian political

reforms, and increased government intervention in social and

economic affairs. Of these, the area that has received the least

study has been the area of political reform. We now know that

despite the rhetoric of increased political participation and despite

the achievement of reforms like the direct primary and the direct

election of senators, in fact political participation declined dras

tically in the progressive era. Whereas in 1896 roughly 85 percent

of the potential electorate actually voted in the presidential elec

tion, by 1904 that figure had declined to about 65 percent, and it

eroded still further in the years thereafter. Why was this so?

Walter Dean Burnham writes that the chief function of the

"fourth party system" was "the substantially complete insulati

of elites from attacks by the victims of the industrializing process

and a corresponding reinforcement of political conditions favori

an exclusively private exploitation of the industrial economy."

This is an objective not unlike that Samuel Hays has attributed

to certain urban reformers, but other than his work and Jam

Weinstein's on the city commission and manager movements, w

have few systematic studies of the rather striking disparity betwe

progressive majoritarian ideology and the real results of elector

reform. What evidence there is, however, tends strongly to s

stantiate the conclusion that in electoral matters progressivism

was in effect a conservative, even reactionary, affair.

There is another problem that deserves more attention. It i

the problem that new left writers in particular have urged upo

us: the relation of the state to the economic order. Too much of

the work on this question has been plagued either by the facile

liberal assumption that the state always asserts the public interest

27 Walter Dean Burnham, "Party Systems and the Political Process," in Walter

Dean Burnham and William Nisbet Chambers, eds., The American Party Systems:

Stages of Political Development (New York, 1967), 301.

466

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Overview

or by a version of the Marxist postulate that the state is only the

executive committee of the ruling class and that its role, therefore,

must be simply to reinforce the pre-existing economic realities.

In fact, in a formally democratic system, once the premise is

granted that the state has a legitimate role to play in economic

matters —and the legitimating of that premise was one of the

things with which progressivism was most concerned — then the

precise use and influence of the state's power is up for grabs. It

is up for grabs not only in the drafting of the original legislation,

but continuously in the operation of the agencies in question.

Any judgment about the nature and employment of political power

in the economy, therefore, cannot rest on legislative history alone.

To be more specific, one of the principal weaknesses of Kolko's

account of "political capitalism" is the fact that his book ends

in 1916. The evidence that he presents — that business groups

were interested in and significantly shaped legislation that was

allegedly intended to regulate those very groups — should surprise

no one, and it is not, by itself, very interesting or conclusive

information. What we need are more histories of agencies and

industries over time that will allow more conclusive judgments

on the very important issues he raises.

Such histories will prove most profitable if they proceed from

an informed consciousness of the uniqueness to America of the

institution of the independent regulatory commission. The

ideology behind that institution is one with deep roots in the

American political tradition, stemming from eighteenth-century

notions about limited and divided sovereignty, and reflecting the

progressive period's distinctive fusion of the traditional fear of

power that is a legacy from the Revolutionary period with the

late nineteenth-century faith in the neutrality and beneficence of

science. Ironically, political scientists like Grant McConnell and

Theodore Lowi seem more sensitive to these historical considera

tions than most historians who write about the modern era.28 We

need, in short, to deepen our understanding of the peculiarly

American context of political economy through comparative study.

Ours is a notoriously, and sadly, parochial guild, but surely there

is much to be learned from comparing the progressive experience

with reform efforts in other industrial societies.

Finally, we must recapture the historicity of the progressive

period. J. R. Pole has remarked that Americans lack "that sense,

inescapable in Europe, of the total, crumbled irrecoverability of

the past, of its differentness, of the fact that it is dead."29 If that

28 See Grant McConnell, Private Power and American Democracy (New York,

1967), and Theodore Lowi, The End of Liberalism (New York, 1969).

M Quoted in John Higham, Writing American History: Essays on Modem

Scholarship (Bloomington, 1970), 166.

467

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historian

is a failing of American culture it is one that American historian

— who might be expected to have a certain immunity from such

an attitude — have not managed to escape. The instrumental

orientation of progressive historiography, which despite everything

seems still to be our dominant tradition, makes easy, even nece

sary, the assumption that the past is closely related to the present.

Virtually everyone who has written about the progressive era ha

made that assumption (Wiebe, for example, says that "we are

asked to see the shape of our time, however rough, emergin

around those years").30 One consequence has been the heaping

upon the heads of the progressives the blame for a good many

problems that might best be laid at the door of later generations

Of the authors considered here, only Richard Hofstadter (and

one might also mention his student, Otis Graham) seemed deeply

to appreciate the gulf that separates the progressives from us. Much

of the confusion and contradiction that his pages registered

reflected not so much the deficiencies of his own analysis as the

unavoidable ambiguities facing a generation whose task it was t

begin the transformation of the liberal tradition from a defense

against state power to a justification for it. In the realm of political

economy, one splendid recent monograph, Robert Cuff's Τ he Wa

Industries Board, has noted the tendency of almost all other recent

students of the progressive period to "exaggerate the modernity of

America's response to the crisis of World War I." In fact, he

finds, the War Industries Board, so often cited as a typicall

progressive accomplishment and a link to the revival of reform in

the New Deal, reveals the "complexity, hesitancy, and ambiguity

with which government and business leaders alike approached war

mobilization. All parties concerned, writes Cuff, felt a profound

"ambiguity toward the role of the state."31

The progressive era, in sum, was an era of transition, and that

transitional character is one of its most significant aspects. We

cannot look to it for the source of all aspects of our modern life

nor can we make the progressives the heroes or the scapegoats fo

the triumphs or failings, as the case may be, of the rest of the

century. Progressivism, after all, is past, and must be so treated

But past does not mean irrelevant, and certainly does not mean

nonexistent. The persistent interest in progressivism as an object

of study, and the wide range of important and interesting work tha

remains to be done, prompt the conclusion that, as with Mark

Twain, reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated.

30 Wiébe, "The Progressive Years," 426.

81 Robert D. Cuff, The War Industries Board: Business-Government Relations

During World War I (Baltimore, 1973), 5-7.

468

This content downloaded from

41.229.228.11 on Fri, 23 Feb 2024 09:30:07 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Canovan 1981 PDFDocument178 pagesCanovan 1981 PDFBen100% (1)

- O'Donnell y Schmitter - Transitions From Authoritarian Rule. Tentative Conclusions About Uncertain DemocraciesDocument94 pagesO'Donnell y Schmitter - Transitions From Authoritarian Rule. Tentative Conclusions About Uncertain DemocraciescarlosusassNo ratings yet

- The French Idea of Freedom: The Old Regime and the Declaration of Rights of 1789From EverandThe French Idea of Freedom: The Old Regime and the Declaration of Rights of 1789No ratings yet

- Escobar Beyond Search ParadigmDocument4 pagesEscobar Beyond Search ParadigmAmmar RashidNo ratings yet

- Matthew Simpson - Rousseau's Theory of Freedom-Continuum (2006)Document137 pagesMatthew Simpson - Rousseau's Theory of Freedom-Continuum (2006)MounirNo ratings yet

- Judith Butler-Who Owns KafkaDocument21 pagesJudith Butler-Who Owns KafkaStrange ErenNo ratings yet

- Classic DragDocument12 pagesClassic Draganna kosiarekNo ratings yet

- The Idea of a Liberal Theory: A Critique and ReconstructionFrom EverandThe Idea of a Liberal Theory: A Critique and ReconstructionRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- PhillipsFein ConservatismStateField 2011Document22 pagesPhillipsFein ConservatismStateField 2011Federico PerelmuterNo ratings yet

- Fowler FallConsensus 2021Document34 pagesFowler FallConsensus 2021sangbarto basuNo ratings yet

- Funding MovementDocument6 pagesFunding MovementMarikNo ratings yet

- Secularization of PostmillenialismDocument21 pagesSecularization of PostmillenialismJames RuhlandNo ratings yet

- Fernandez 2003 - Despre MarxDocument31 pagesFernandez 2003 - Despre MarxMarius Andrei SpînuNo ratings yet

- What Is FeminismDocument40 pagesWhat Is FeminismElena Oroz100% (1)

- Conservatism A State of FieldDocument21 pagesConservatism A State of Fieldcliodna18No ratings yet

- The Post-Modernism of The Right and The Need For Constructive ThinkingDocument29 pagesThe Post-Modernism of The Right and The Need For Constructive Thinkingddbd30No ratings yet

- American Historiography Richard HofsterdatDocument30 pagesAmerican Historiography Richard HofsterdatSritamaNo ratings yet

- Jewish Weimar RepublicDocument17 pagesJewish Weimar RepublicRaúlNo ratings yet

- Phillips Fein ConservatismDocument21 pagesPhillips Fein ConservatismTalia ShabtayNo ratings yet

- 4284801Document16 pages4284801Christian MatroneNo ratings yet

- Sunstein Liberalism Ruined 2019Document13 pagesSunstein Liberalism Ruined 2019Dušan PavlovićNo ratings yet

- Edward Said and The Politics of Worldliness - Toward A "Rendezvous of Victory": Henry A. GirouxDocument11 pagesEdward Said and The Politics of Worldliness - Toward A "Rendezvous of Victory": Henry A. GirouxMaiko CheukachiNo ratings yet

- The Vanishing Tradition: Perspectives on American ConservatismFrom EverandThe Vanishing Tradition: Perspectives on American ConservatismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Morgenthau 1952Document49 pagesMorgenthau 1952是No ratings yet

- Morgenthau 1952Document29 pagesMorgenthau 1952是No ratings yet

- The Debate Over Slavery: Antislavery and Proslavery Liberalism in Antebellum AmericaFrom EverandThe Debate Over Slavery: Antislavery and Proslavery Liberalism in Antebellum AmericaNo ratings yet

- Feinberg PhilosophyEastWest 1975Document6 pagesFeinberg PhilosophyEastWest 1975wr7md5b55fNo ratings yet

- Hegemony - and - Education - Gramsci, Post-Marxism, and Radical Democracy RevisitedDocument276 pagesHegemony - and - Education - Gramsci, Post-Marxism, and Radical Democracy RevisitedRaif Qela100% (1)

- Progressives A CritiqueDocument13 pagesProgressives A CritiquevkveronaNo ratings yet

- 7 Foundations and CollaborationDocument27 pages7 Foundations and CollaborationDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- Regarding Politics: Essays on Political Theory, Stability, and ChangeFrom EverandRegarding Politics: Essays on Political Theory, Stability, and ChangeNo ratings yet

- Roosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Economics of RecoveryFrom EverandRoosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Economics of RecoveryNo ratings yet

- Can The Philosopher Influence Social Change, 1954Document14 pagesCan The Philosopher Influence Social Change, 1954cauim.ferreiraNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and Its Comparative Education ImplicationsDocument18 pagesPostmodernism and Its Comparative Education ImplicationsLetta ZaglaNo ratings yet

- Voegelin 1944 IVDocument10 pagesVoegelin 1944 IVRene PlascenciaNo ratings yet

- Analyszing Social MovementDocument5 pagesAnalyszing Social MovementVinisa N. AisyahNo ratings yet

- Essay en Droit InternationalDocument5 pagesEssay en Droit InternationalGrace LuNo ratings yet

- Transcending Capitalism: Visions of a New Society in Modern American ThoughtFrom EverandTranscending Capitalism: Visions of a New Society in Modern American ThoughtNo ratings yet

- The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on TheoryFrom EverandThe Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on TheoryNo ratings yet

- Fascism and ModernizationDocument19 pagesFascism and ModernizationKarmen ZCNo ratings yet

- ANDREWSeBAWA, PosdevelopmentDocument18 pagesANDREWSeBAWA, PosdevelopmentGiovanna Migliori SemeraroNo ratings yet

- Global History of Modernity - Der Veer 1998Document11 pagesGlobal History of Modernity - Der Veer 1998ambulafiaNo ratings yet

- The Union at Risk. Jacksonian Democracy, States Rights, and Nullification CrisisDocument280 pagesThe Union at Risk. Jacksonian Democracy, States Rights, and Nullification CrisisDamian HemmingsNo ratings yet

- Social Darwinism: Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social ThoughtFrom EverandSocial Darwinism: Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social ThoughtRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- American Economics: The Character of The Transformation: Mary S. Morgan and Malcolm RutherfordDocument26 pagesAmerican Economics: The Character of The Transformation: Mary S. Morgan and Malcolm RutherfordCesar Jeanpierre Castillo GarciaNo ratings yet

- Oxford University Press, American Historical Association The American Historical ReviewDocument23 pagesOxford University Press, American Historical Association The American Historical ReviewEiriniEnypnioNo ratings yet

- Shimko (1992) - Realism, Neorealism, and American LiberalismDocument22 pagesShimko (1992) - Realism, Neorealism, and American LiberalismJoao Estevam100% (1)

- H. Turner, Fascism and ModernizationDocument19 pagesH. Turner, Fascism and ModernizationGelu Cristian SabauNo ratings yet

- Ryan 2020Document16 pagesRyan 2020Mikki SchindlerNo ratings yet

- History As Progress ReviewDocument3 pagesHistory As Progress Reviewstfu.dNo ratings yet

- The Limits of Progressivism - Boundless US HistoryDocument11 pagesThe Limits of Progressivism - Boundless US HistoryRosa EternaNo ratings yet

- Mitchell WJT 2004 Medium TheoryDocument12 pagesMitchell WJT 2004 Medium Theoryh.omarquijanoNo ratings yet

- 405 Interview NashDocument7 pages405 Interview NashClifford Angell BatesNo ratings yet

- Progress: Progress Is The Movement Towards ADocument91 pagesProgress: Progress Is The Movement Towards AAngie PojasNo ratings yet

- Us Versus Them': Abortion and The Rhetoric of The New RightDocument16 pagesUs Versus Them': Abortion and The Rhetoric of The New RightLuciano OLiveiraNo ratings yet

- What Is The Social in Social History? Patrick JoyceDocument36 pagesWhat Is The Social in Social History? Patrick JoyceFelo Morales BarreraNo ratings yet

- Neo Evolutionary, Modernisation, Neo ModernisationDocument30 pagesNeo Evolutionary, Modernisation, Neo ModernisationAqilla FadyaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 102.176.65.72 On Sat, 09 Jul 2022 08:06:27 UTCDocument34 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 102.176.65.72 On Sat, 09 Jul 2022 08:06:27 UTCkay addoNo ratings yet

- Law As A Social ChangeDocument4 pagesLaw As A Social ChangeArun SangwanNo ratings yet

- Kashmir Human Rights ReportDocument72 pagesKashmir Human Rights ReportThe Wire67% (6)

- Uniform Civil CodeDocument11 pagesUniform Civil CodeRaghuvansh MishraNo ratings yet

- Double Lives Stalin, Willi Munzenberg and The Seduction of The Intellectuals (Stephen Koch) (Z-Library)Document448 pagesDouble Lives Stalin, Willi Munzenberg and The Seduction of The Intellectuals (Stephen Koch) (Z-Library)deusnoririkuNo ratings yet

- Gsic Lexus Rx350 Rx270 Ggl15 Agl10 2008 2011 Workshop ManualDocument22 pagesGsic Lexus Rx350 Rx270 Ggl15 Agl10 2008 2011 Workshop Manualdavidmiller030201igj100% (95)

- 10 Benitez Vs Sta FeDocument4 pages10 Benitez Vs Sta FeLucille ArianneNo ratings yet

- JWLA-025 Gulf of Guinea2Document3 pagesJWLA-025 Gulf of Guinea2vodoley634No ratings yet

- Social WelfareDocument5 pagesSocial Welfarepatelshivani033No ratings yet

- Migration and Discrimination - Non-Discrimination As Guardian Against Arbitrariness or Driver of Integration - Wouter VandenholeDocument23 pagesMigration and Discrimination - Non-Discrimination As Guardian Against Arbitrariness or Driver of Integration - Wouter VandenholeJuan Jose Garzon CamposNo ratings yet

- March13.2012 - B House Body Urges TRB To Collect PNCC's P4 Billion Unpaid Concession FeesDocument1 pageMarch13.2012 - B House Body Urges TRB To Collect PNCC's P4 Billion Unpaid Concession Feespribhor2No ratings yet

- Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada: Joeriz Apuada SimbilloDocument15 pagesFidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada: Joeriz Apuada SimbilloAprilRoseGonzalVitalNo ratings yet

- Youth Engagement and Empowerment ReportDocument54 pagesYouth Engagement and Empowerment ReportRhyle ReyesNo ratings yet

- Delimitation ClarificationsDocument2 pagesDelimitation ClarificationsJegannath JNo ratings yet

- Saa 2015Document150 pagesSaa 2015Anisa UtamiNo ratings yet

- AndhraPradesh DV List1Document97 pagesAndhraPradesh DV List1Jahnavi PutrevuNo ratings yet

- Predominance of Legal SpiritDocument4 pagesPredominance of Legal SpiritpraharshithaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Community Policing - Handout2aDocument3 pagesBenefits of Community Policing - Handout2astylo467567% (3)

- Presentation 1Document10 pagesPresentation 1Dp Brawl StarsNo ratings yet

- CapitalismDocument14 pagesCapitalismShrey SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Klingelhoeffer: An Early German Immigrant in ArkansasDocument8 pagesRevisiting Klingelhoeffer: An Early German Immigrant in ArkansasDanWDurningNo ratings yet

- Eshal Zainab Pary - 8C - SST - Holiday Homework Q.1Document2 pagesEshal Zainab Pary - 8C - SST - Holiday Homework Q.1EshalNo ratings yet

- Behavior RubricDocument3 pagesBehavior RubricSuresh DassNo ratings yet

- Boy Scouts of The Philippines v. Commission On AuditDocument3 pagesBoy Scouts of The Philippines v. Commission On AuditNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

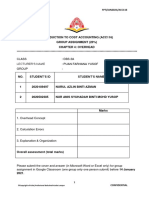

- Group Assignment Acc116Document9 pagesGroup Assignment Acc116Nurul AzlinNo ratings yet

- CDM WagombeaDocument6 pagesCDM WagombeangabweNo ratings yet

- The Iron WallDocument7 pagesThe Iron WallYassmina Adham OrbanNo ratings yet

- Overview of CPPDocument19 pagesOverview of CPPHedjarah M. Hadji Ameen100% (1)

- Gustav Von Schmoller - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument4 pagesGustav Von Schmoller - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaClaviusNo ratings yet