Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Grit - CDSE Mexican Vela

Uploaded by

Ruth Gnadea SilalahiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Grit - CDSE Mexican Vela

Uploaded by

Ruth Gnadea SilalahiCopyright:

Available Formats

Received 07/09/15

Revised 09/21/15

Accepted 09/23/15

•

DOI: 10.1002/joec.12070

the role of character strengths and

importance of family on mexican

american college students’

career decision self-efficacy

Javier Cavazos Vela, Gregory Scott Sparrow,

James F. Whittenberg, and Basilio Rodriguez

This study examined how character strengths and the importance of family influenced

Mexican American college students’ (N = 129) career decision self-efficacy. Findings

from a multiple regression analysis indicated that psychological grit and curiosity

were significant predictors of career decision self-efficacy. The authors discuss the

importance of these findings and provide recommendations for future research.

Keywords: character strengths, family, career decision self-efficacy, psychological

grit, curiosity

The Hispanic population is one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United

States, with Mexican Americans making up the largest subgroup of this population

(U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Compared with 30.3% of Whites, 10.6% of Mexican

Americans received a college degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Although career

services have improved for the growing Hispanic population, Mexican American

students pursuing postsecondary education and career selection face individual,

interpersonal, and institutional challenges (Vela, Lu, Veliz, Johnson, & Castro,

2014). Some of these challenges include low self-esteem, lack of motivation, minimal

support from counselors or teachers, socioeconomic issues, and insufficient college

information. Despite the importance of educational research, there is a dearth of

literature regarding how character strengths and the importance of family influence

Mexican American college students’ career development. One of the most important

constructs in career development is career decision self-efficacy (CDSE; Taylor &

Betz, 1983). Given that CDSE is positively related to educational outcomes, career

satisfaction, and life satisfaction, investigating predictors of CDSE is a worthwhile

research endeavor.

In the current study, we use a theoretical framework that consists of character

strengths and importance of family to determine which character strengths are associated

Javier Cavazos Vela, Gregory Scott Sparrow, James F. Whittenberg, and Basilio Rodriguez, Depart-

ment of Counseling and Guidance, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Correspondence concerning

this article should be addressed to Javier Cavazos Vela, Department of Counseling and Guidance,

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, One West University Drive, Main 2.200D, Brownsville, TX

78520 (e-mail: javier.cavazos@utrgv.edu).

© 2018 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved.

16 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

with Mexican American students’ CDSE. First, we provide a literature review with

theoretically and empirically relevant studies on character strengths and importance

of family. Next, we present quantitative findings from 129 Mexican American college

students from a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI). Finally, we discuss the importance

of these findings and the implications for practice and research.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

A useful conceptual approach to understand human development is positive psychol-

ogy (Seligman, 2002). Rather than examining deficits, positive psychology focuses

on strengths, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction (Vela, Castro, Cavazos,

Cavazos, & Gonzalez, 2014). Researchers have used positive psychology to understand

academic achievement, positive psychological functioning, and career development

outcomes. By using a positive psychology paradigm, researchers understand how

character strengths contribute to students’ or adults’ positive psychological func-

tioning and resilience (Seligman, 2002; Snyder & Lopez, 2007). Character strengths

refer to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that can help youth reach their potential

and personal well-being (Park, 2004; Toner, Haslam, Robinson, & Williams, 2012).

Although positive psychology has identified 24 character strengths, we focus on

psychological grit, curiosity, optimism, and gratitude in the current study. These

four character strengths have been associated with important academic and mental

health outcomes. Therefore, we suggest that these character strengths might also

influence CDSE. The Character Lab (2015) endorsed curiosity, gratitude, optimism,

and grit as important character strengths to understand adolescents’ academic and

other important outcomes.

One of the most important character strengths is psychological grit because of

its relationship with academic outcomes (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly,

2007). Psychological grit (henceforth grit in this article) is defined as passion for

long-term goals and applied efforts toward goals (Duckworth & Eskreis-Winkler,

2015; Duckworth et al., 2007). Researchers found that grit is positively related to

academic performance (Duckworth et al., 2007), performance in the National Spelling

Bee (Duckworth et al., 2007), well-being (Salles, Cohen, & Mueller, 2014), exercise

behaviors (Reed, 2012), and hope (Vela, Lu, Lenz, & Hinojosa, 2015). Curiosity is

another important character strength and consists of stretching (i.e., the tendency

to explore new experiences) and embracing (i.e., readiness to accept new situations)

perspectives (Jovanovic & Gavrilov-Jerkovic, 2014). Researchers identified curiosity

as a characteristic of personal growth and psychological strength (Kashdan, Rose, &

Fincham, 2004; Peterson & Seligman, 2004) that is related to life satisfaction, hope

(Jovanovic & Brdaric, 2012; Kashdan, McKnight, Fincham, & Rose, 2011), academic

success, and positive perceptions of learning environments (Kashdan & Yuen, 2007).

Two other important character strengths that might influence career development

are optimism and gratitude. Vacek, Coyle, and Vera (2010) defined optimism as

the expectation that positive things will happen in life. Optimism has been linked

to psychological health, and schools play an important role in enhancing students’

optimism (Mannix, Feldman, & Moody, 2009; Puskar et al., 2010). Puskar et al.

journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55 17

(2010) found that girls had lower levels of self-esteem and optimism when compared

with boys. In addition, Kleiman, Adams, Kashdan, and Riskind (2013) defined

gratitude as mindful appreciation that arises from kindness to others. Gratitude

has been positively related to grit and protective factors and negatively related to

suicidal ideation and attempts (Li, Zhang, Li, & Ye, 2012; Ma, Kibler, & Sly, 2013).

Froh et al. (2014) posited that experiencing and expressing gratitude is a simple way

to counter negative appraisals, increase social adjustment, strengthen supportive

relationships, and increase prosocial behavior.

In summary, grit, curiosity, gratitude, and optimism have been theoretically and

empirically linked (Character Lab, 2015) to adolescents’ and college students’ aca-

demic and mental health outcomes. In addition to character strengths, the importance

of family should be included as part of the conceptual framework to understand

Mexican American students’ career development outcomes.

The importance of family has consistently been found to affect Mexican American

students’ academic performance, resilience, career development, and mental health

(Cavazos et al., 2010; Vela, Lenz, Sparrow, Gonzalez, & Hinojosa, 2015). Marin and

Marin (1991) defined familismo as loyalty and solidarity to the family unit, with im-

portant parts involving family identity, mutual family activities, and family cohesion

(Jose, Ryan, & Pryor, 2012). Researchers illustrated that importance of family is

positively related to the academic resilience and mental health of Mexican American

adolescents and adults alike (Cavazos et al., 2010; Vela, Lenz, et al., 2015). For

example, Vela, Lenz, et al. (2015) examined positive psychology and family factors

as predictors of Mexican American adolescents’ vocational outcome expectations.

Presence of meaning in life and importance of family were predictors of vocational

outcome expectations. In another investigation, Vela, Smith, Hinojosa, Dell Aquila,

and Ortega (in press) examined positive psychology, career, and family predictors of

Mexican American college students’ positive psychological functioning. They found

that students’ perceptions of importance of family predicted subjective happiness.

In sum, because researchers found that the importance of family influenced college

students’ character strengths (e.g., psychological grit; Vela, Lu, et al., 2015), we

include importance of family as part of a conceptual framework to understand CDSE.

CDSE

CDSE refers to how confident individuals are in their ability to choose and com-

mit to a career (Taylor & Betz, 1983). CDSE is negatively related to loss of wages,

underemployment, indecisiveness, and attitudes toward early careers and jobs

(Feldman, 2003). Researchers have highlighted how CDSE is positively related to

educational outcomes (Flores, Ojeda, Huang, Gee, & Lee, 2006) and life satisfaction

(Pina-Watson, Jimenez, & Ojeda, 2014). Given that CDSE is positively related to

educational outcomes and mental health, researchers have begun to identify factors

that influence CDSE. Wright, Perrone-McGovern, Boo, and White (2014) examined

attachment supports and career barriers on college students’ CDSE. Higher percep-

tions of support were related to higher levels of CDSE, whereas higher perceptions

18 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

of barriers were negatively related to CDSE. Burns, Jasinski, Dunn, and Fletcher

(2013) investigated student-athletes’ perceptions of academic support services and

CDSE and found that perceptions of academic services were positively related to

CDSE. Although researchers have examined the relationship between perceptions

of support and barriers on CDSE, less attention has been given to the role of char-

acter strengths and the importance of family, particularly among Mexican American

college students. Research is necessary to determine which character strengths

influence CDSE.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

Understanding how character strengths and the importance of family influence

Mexican American students’ CDSE is an overriding issue in postsecondary educa-

tion (Pina-Watson et al., 2014). Although some studies have investigated Mexican

American college students’ CDSE, no study has examined how character strengths

and importance of family affect CDSE. There is a dearth of information investigat-

ing how character strengths interact with importance of family within the Mexican

American community. The lack of literature in this area underscores the need to

examine how specific character strengths might affect CDSE. Therefore, we explored

the following research question: To what extent do psychological grit, curiosity,

gratitude, optimism, and importance of family influence Mexican American college

students’ CDSE?

METHOD

Participants

The first author identified large undergraduate courses from an HSI in the southern

region of the United States from which to recruit Mexican American participants. We

used purposive sampling with undergraduate classes to ensure Mexican American

students were included in the sample. The HSI had an enrollment of around 7,000

undergraduate and graduate students (approximately 93% of students at this institution

are Latina/o). A total of 129 students who were enrolled at the HSI provided data.

The sample included 52 men (40.9%) and 75 women (59.1%). Of the participants,

72 (56.7%) self-identified as Latina/o or Hispanic, 40 (31.5%) described themselves

as Mexican American, and 15 (11.8%) indicated a Mexican ethnic identity. Two

participants did not report their gender or other demographic information.

Measures

Psychological grit. The Short Grit Scale (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) measures

students’ perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Participants respond

to statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me)

to 5 (very much like me). An example of one of the statements is “Setbacks

journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55 19

don’t discourage me.” The mean score for this study was 3.41 (SD = 0.66).

Reliability coefficients range from .78 to .82 (Duckworth, Kirby, Tsukayama,

Berstein, & Ericsson, 2011; Reed, 2012). For the current study, Cronbach’s

alpha was .77.

Curiosity. The Curiosity and Exploration Inventory (Kashdan et al., 2009) measures

participants’ levels of curiosity. Participants respond to items on a 5-point Likert-

type scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Sample items

include “I actively seek as much information as I can in new situations” and “I am

the type of person who really enjoys the uncertainty of everyday life.” The mean

score for this study was 3.64 (SD = 0.77). Reliability coefficients range from .76

to .77 (Jovanovic & Brdaric, 2012; Jovanovic & Gavrilov-Jerkovic, 2014). For the

current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Optimism. The Life Orientation Test (Scheier & Carver, 1985) measures partici-

pants’ optimism. Participants respond to items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging

from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Sample items include “In uncertain

times, I usually expect the best” and “If something can go wrong for me, it will.”

The mean score for this study was 14.45 (SD = 3.45). Reliability coefficients range

from .70 to .78 (Puskar et al., 2010; Vacek et al., 2010). For the current study,

Cronbach’s alpha was .83.

Gratitude. The Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002)

measures participants’ tendency to feel gratitude. Participants respond to items on a

7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample

items include “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “I am grateful to a wide

variety of people.” The mean score for this study was 6.09 (SD = 1.05). Reliability

coefficients range from .83 to .88 (Kleiman et al., 2013; Li et al., 2012). One of the

items (Item 6) was problematic and was removed from the average score computation,

yielding a reliability coefficient for data in the good range (.89).

Importance of family. The Pan-Hispanic Familism Scale (Villareal, Blozis, & Wi-

daman, 2005) measures one’s perceptions of the importance of family. Participants

respond to statements evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly

disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample response items include “I am proud of my

family” and “I cherish the time I spend with my family.” The mean score for this

study was 4.28 (SD = 0.97). Reliability coefficients range from .83 to .87 (Pina-

Watson, Ojeda, Castellon, & Dornhecker, 2013; Vela, Lenz, et al., 2015). For the

current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .93

CDSE. The CDSE Scale–Short Form (Betz & Taylor, 2001) measures students’

CDSE. The scale contains five subscales: Self-Appraisal, Occupational Infor-

mation, Goal Selection, Planning, and Problem Solving. Participants respond to

items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (no confidence at all) to 5

(complete confidence). Sample items include “Make a career decision and then

not worry whether it was right or wrong” and “Prepare a good résumé.” The

mean score for this study was 3.91 (SD = 0.72). Reliability coefficients range

from .91 to .94 (Burns et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2014). For the current study,

Cronbach’s alpha was .95.

20 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

Procedure

We implemented several steps to gather data for the current study. First, we obtained

permission from the institutional review board of the HSI. Second, we informed

participants that participation was voluntary and would not affect their grade in the

class or their enrollment at the university. We obtained informed consent from all

participants in the study.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients are included in Table 1. We

used an alpha level of .05 for this study. To evaluate multicollinearity, we inspected

bivariate correlations and variance inflation factors (see Table 1). Low intercorrelations

among predictor variables and variance inflation factors were within the acceptable

range (Vela, Lenz, et al., 2015), providing evidence for a single regression model.

Primary Analyses

We conducted a multiple regression analysis on CDSE based on optimism, curiosity,

grit, importance of family, and gratitude. We used multiple regression to predict the

criterion variable of CDSE. Multiple regression is the appropriate statistical analysis

when researchers predict a continuous variable based on other variables (Dimitrov,

2013). After analyzing scatterplots, we found no evidence of curvilinear relation-

ships between the criterion variable and predictor variables or heteroscedascity.

There was a statistically significant relationship between the predictor variables

and CDSE, F(5, 129) = 19.45, p < .001, thus providing evidence that the variance

in CDSE accounted for by the predictor variables does not equal zero for the popu-

lation (Dimitrov, 2013). A large effect size of R2 = .44 was noted, indicating that

44% of the students’ differences in CDSE were accounted for by their differences

in predictor variables in the current study.

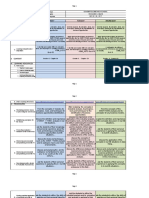

TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

for the Predictor Variables

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 VIF

1. Optimism 14.45 3.45 — .39 .37 .41 .31 1.38

2. Curiosity 3.64 0.77 — .40 .36 .24 1.34

3. Grit 3.42 0.66 — .37 .22 1.33

4. Importance of family 4.28 0.97 — .40 1.45

5. Gratitude 6.09 1.05 — 1.23

Note. VIF = variance inflation factor.

journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55 21

After establishing the overall statistical significance of R2 and the multiple regres-

sion equation, we examined the statistical significance of the regression coefficients

for significant predictors (Dimitrov, 2013). Both grit and curiosity had unique con-

tributions to the explanation of variance in CDSE. Grit was a statistically significant

predictor of CDSE (see Table 2), accounting for approximately 13% of the variance.

Curiosity was also a statistically significant predictor of CDSE, accounting for 14%

of CDSE. Optimism, gratitude, and importance of family were not statistically sig-

nificant predictors of CDSE.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to our understanding of Mexican American college students’ career

development by exploring the relationships among character strengths and importance of

family in a multidimensional manner. The study augments previous studies on Mexican

American college students’ career development by examining different variables. We

suggest that our findings have potential to shape interventions and programs to improve

Mexican American college students’ career development. Although not all character

strengths in our study predicted CDSE, future research could use other factors as part

of a framework to examine Mexican American students’ career development outcomes.

There are several important findings in the current study. The two character

strengths predictive of CDSE—grit and curiosity—can be viewed as dynamic

qualities that manifest in a psychological state of arousal or tension. This study

suggests that as grit and curiosity increase, the level of CDSE increases. This is

one of the first studies to highlight how grit and curiosity are positively related

to Mexican American college students’ CDSE. From this perspective, it makes

sense that these two characteristics would prompt an individual to take initia-

tive toward resolving a state of tension related to unmet personal and career

goals, thus subsequently experiencing higher levels of confidence relating to

career decisions. In contrast, optimism, gratitude, and importance of family

can be viewed as static qualities occurring in a relative state of equilibrium or

contentment. If so, high levels of optimism, gratitude, and importance of family

could work bidirectionally, leading some students to have more confidence to

take initiative in pursuing new directions and other students to accept the status

quo from the standpoint of relative contentment.

TABLE 2

Multiple Regression Results for Career-Decision Self-Efficacy

Variable B SE B b t p sr2

Optimism .10 .02 .04 0.53 .60 .00

Curiosity .33 .07 .35 4.55 .000* .14

Grit .37 .09 .33 4.31 .000* .13

Importance of family .07 .06 .10 1.17 .24 .01

Gratitude .04 .05 .05 0.72 .48 .00

*p < .05.

22 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

Implications for Practice

Professional counselors in high school and college settings play an important role

in students’ career development. On the basis of our findings, counselors should

consider helping students to develop grit and curiosity. Grit has been positively

associated with lifetime educational attainment, academic achievement, persistence

(Duckworth et al., 2007), and CDSE. Therefore, if college counselors adopt strategies

and interventions to develop Mexican American students’ grit, they can help these

students improve their CDSE. Possible strategies include using assessments that

measure students’ grit and then following up with a plan of action to increase grit;

helping students find a career they will be passionate about; and determining how

students will achieve, persist, and strengthen their grit when disappointment arises.

In addition, curiosity has been linked with personal growth, psychological strength

(Kashdan et al., 2004; Peterson & Seligman, 2004), and now CDSE. Curiosity

enables individuals to thrive and develop a sense of subjective and psychological

well-being (Jovanovic & Gavrilov-Jerkovic, 2014). As a result, counselors might

consider avenues for students to increase their curiosity (Jovanovic & Gavrilov-

Jerkovic, 2014) and awareness of job opportunities, as well as strategies to help

students reach full potential. This means that if counselors discuss job opportunities

and career aspirations with students, the students might be more likely to become

curious and explore new opportunities. Finally, because the findings of this study

link curiosity to CDSE, counselors might consider developing innovative ways to

increase students’ curiosity about and awareness of job opportunities. Given the

increasing availability of YouTube videos and podcasts, counselors can accumulate

a catalog of online audiovisual enticements for students who might otherwise show

minimal interest in a particular career track.

Implications for Research

We recommended some directions for future research. First, more outcome-based

research is needed to determine which strategies or interventions improve students’

grit and curiosity. Several possible interventions include narrative therapy (White

& Epston, 1990) and positive psychology (Seligman, 2002). Second, future research

can benefit from an ecological framework to explore how individual, interpersonal,

and institutional factors affect Mexican American students’ CDSE. For Mexican

American high school students, some institutional factors include perceptions of

school climate and a college-going culture (Vela, Lu, et al., 2015). In addition, it is

important to conduct longitudinal studies to understand temporal changes in factors

that affect Mexican American students’ career development.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we relied on cross-sectional data, which

limit cause-and-effect inferences (Vela, Lu, et al., 2014). Second, we relied on

journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55 23

students’ self-reported perceptions of character skills and importance of family. We

acknowledge that some students may lack insight into their feelings and percep-

tions or may have provided socially desirable responses (Alvarado & Ricard, 2013;

Vela, Lu, et al., 2015; Zalaquett, 2006). Third, the homogeneity of the university

and its environment might affect generalizability (Watson, 2009). The students in

our sample attended an HSI with over 93% Hispanic students, thereby limiting

applicability of our findings to Mexican American students who attend similar in-

stitutions. Furthermore, we surveyed only successful Mexican American students,

as defined by enrollment in postsecondary education. It would be interesting to

conduct a similar study on Mexican American high school students’ or community

college students’ career development.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study point to the importance of exploring factors associated

with Mexican American college students’ CDSE. Counselors can assist Mexican

American college students become aware of the importance of grit and curiosity and

use interventions to increase Mexican American adolescents’ career development.

Researchers can endeavor to assess other character strengths and interpersonal factors

to support the emerging framework for predicting Mexican American adolescents’

career development outcomes.

REFERENCES

Alvarado, M., & Ricard, R. J. (2013). Developmental assets and ethnic identity as predictors

of thriving in Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 34, 510–523.

doi:10.1177/0739986313499006

Betz, N. E., & Taylor, K. M. (2001). Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scale–Short Form. Columbus, OH: The

Ohio State University, Department of Psychology.

Burns, G. N., Jasinski, D., Dunn, S., & Fletcher, D. (2013). Academic support services and career

decision-making self-efficacy in student athletes. The Career Development Quarterly, 61, 161–167.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00044.x

Cavazos, J., Johnson, M. B., Fielding, C., Cavazos, A. G., Castro, V., & Vela-Gude, L. (2010). A

qualitative study of resilient Latina/o students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 9, 172–188.

doi:10.1080/153484431003761166

Character Lab. (2015). Advancing the science and practice of character development. Retrieved from

https://www.characterlab.org/

Dimitrov, D. M. (2013). Quantitative research in education: Intermediate and advanced methods. Oceanside,

NY: Whittier.

Duckworth, A. L., & Eskreis-Winkler, L. (2015). Grit. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia

of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 397–401). Oxford, England: Elsevier.

Duckworth, A. L., Kirby, T. A., Tsukayama, E., Berstein, H., & Ericsson, K. A. (2011). Deliberate practice

spells success: Why grittier competitors triumph at the National Spelling Bee. Social Psychological

and Personality Science, 2, 174–181. doi:10.1177/1948550610385872

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion

for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 1087–1181. doi:10.1037/0022-

3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S).

Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 166–174.

24 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

Feldman, D. C. (2003). The antecedents and consequences of early career indecision among young adults.

Human Resource Management Review, 13, 499–531.

Flores, L. Y., Ojeda, L., Huang, Y., Gee, D., & Lee, S. (2006). The relation of acculturation, problem-

solving appraisal, and career decision self-efficacy to Mexican American high school students’

educational goals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 260–266. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.260

Froh, J. J., Bono, G., Fan, J., Emmons, R. A., Henderson, K., Harris, C., . . . Wood, A. M. (2014). Nice

thinking! An educational intervention that teaches children to think gratefully. School Psychology

Review, 43, 132–152.

Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., & Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-

being in adolescence over time? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 235–251. doi:10.1111/

j.7795.2012.00783.x

Jovanovic, V., & Brdaric, D. (2012). Did curiosity kill the cat? Evidence from subjective well-being in

adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 380–384.

Jovanovic, V., & Gavrilov-Jerkovic, V. (2014). The good, the bad (and the ugly): The role of curiosity in

subjective well-being and risky behaviors among adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology,

55, 38–44. doi:10.1111/sjop.12084

Kashdan, T. B., Gallagher, M. W., Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. F. (2009). The

Curiosity and Exploration Inventory–II. Development, factor, structure, and psychometrics. Journal

of Research in Personality, 43, 987–998.

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., Fincham, F. D., & Rose, P. (2011). When curiosity breeds intimacy: Taking

advantage of intimacy opportunities and transforming boring conversations. Journal of Personality,

79, 1369–1401. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00697.x

Kashdan, T. B., Rose, P., & Fincham, F. D. (2004). Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjec-

tive experiences and personal growth opportunities. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82, 291–305.

Kashdan, T. B., & Yuen, M. (2007). Whether highly curious students thrive academically depends on

perceptions about the school learning environment: A study of Hong Kong adolescents. Motivation

and Emotion, 31, 260–270.

Kleiman, E. M., Adams, L. M., Kashdan, T. B., & Riskind, J. H. (2013). Gratitude and grit indirectly

reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: Evidence for a mediated moderation

model. Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 539–546.

Li, D., Zhang, W., Li, X., & Ye, B. (2012). Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts

among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Adolescence,

35, 55–66.

Ma, M., Kibler, J. L., & Sly, K. (2013). Gratitude is associated with greater levels of protective factors

and lower levels of risks in African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescents, 36, 983–991.

doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.012

Mannix, M. M., Feldman, J. M., & Moody, K. (2009). Optimism and health-related quality of life in

adolescents with cancer. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 35, 482–488.

Marin, G., & Marin, B. V. (1991). Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and

empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

Park, N. (2004). Character strengths and positive youth development. The Annals of the American Academy

of Political and Social Science, 591, 40–54.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press and Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pina-Watson, B., Jimenez, N., & Ojeda, L. (2014). Self-construal, career decision self-efficacy, and

perceived barriers predict Mexican American women’s life satisfaction. The Career Development

Quarterly, 62, 210–223. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2014.00080.x

Pina-Watson, B., Ojeda, L., Castellon, N. E., & Dornhecker, M. (2013). Familismo, ethnic identity, and

bicultural stress as predictors of Mexican American adolescents’ positive psychological functioning.

Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 204–217.

Puskar, K. R., Bernardo, L. M., Ren, D., Haley, T. M., Tark, K. H., Switala, J., & Siemon, L. (2010).

Self-esteem and optimism in rural youth: Gender differences. Contemporary Nurse, 34, 190–198.

Reed, J. (2012). A survey of grit and exercise behavior. Journal of Sport Behavior, 37, 390–404.

journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55 25

Salles, A., Cohen, G. L., & Mueller, M. D. (2014). The relationship between grit and resident well-being.

The American Journal of Surgery, 207, 251–254.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications to

generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential

for lasting fulfillment. New York, NY: Free Press.

Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2007). Positive psychology: The scientific and practical explorations of

human strengths. London, England: Sage.

Taylor, K. M., & Betz, N. E. (1983). Applications of self-efficacy theory to the understanding and treat-

ment of career decisions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 22, 63–81.

Toner, E., Haslam, N., Robinson, J., & Williams, P. (2012). Character strengths and wellbeing in

adolescence: Structure and correlates of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Children.

Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 637–642.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). Most children younger than age 1 are minorities, Census Bureau reports.

Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-90.html

Vacek, K. R., Coyle, L. D., & Vera, E. M. (2010). Stress, self-esteem, hope, optimism, and well-being

in urban, ethnic minority adolescents. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38,

99–111. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2010.tb00118.x

Vela, J. C., Castro, V., Cavazos, L., Cavazos, M., & Gonzalez, S. L. (2014). Understanding Latina/o students’

meaning in life, spirituality, and subjective happiness. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 14,

171–184. doi:10.1177/1538192714544524

Vela, J. C., Lenz, A. S., Sparrow, G. S., Gonzalez, S. L., & Hinojosa, K. (2015). Humanistic and positive

psychology factors as predictors of Mexican American adolescents’ vocational outcome expectations.

Journal of Professional Counseling: Theory, Research, and Practice, 42, 16–28.

Vela, J. C., Lu, M. T., Lenz, A. S., & Hinojosa, K. (2015). Positive psychology and familial factors as

predictors of Latina/o college students’ psychological grit. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,

36, 452–469.

Vela, J. C., Lu, M. T., Veliz, L., Johnson, M. B., & Castro, V. (2014). Future school counselors’ perceptions

of challenges that Latina/o students face: An exploratory study. VISTAS Online, 39, 1–12. Retrieved

from https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/article_39.pdf?sfvrsn=6

Vela, J. C., Smith, W. D., Hinojosa, K., Dell Aquila, J., & Ortega, K. (in press). Understanding humanistic

and family predictors of Mexican American college students’ subjective happiness. The Journal of

Humanistic Counseling.

Villarreal, R., Blozis, S. A., & Widaman, K. F. (2005). Factorial invariance of a pan-Hispanic familism

scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27, 409–425. doi:10.1177/0739986305281125

Watson, J. C. (2009). Native American racial identity development and college adjustment at two-year

institutions. Journal of College Counseling, 12, 125–136. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2009.tb00110.x

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York, NY: Norton.

Wright, S. L., Perrone-McGovern, K. M., Boo, J. N., & White, A. V. (2014). Influential factors in aca-

demic and career self-efficacy: Attachment, supports, and career barriers. Journal of Counseling &

Development, 92, 36–46. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00128.x

Zalaquett, C. P. (2006). Study of successful Latina/o students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5,

35–47. doi:1177/1538192705282568

26 journal of employment counseling • March 2018 • Volume 55

You might also like

- Ghosh 2017Document6 pagesGhosh 2017Maya NingratNo ratings yet

- Building Hope For The Future - LopezDocument14 pagesBuilding Hope For The Future - LopezPaulo LuísNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Differences: Peter Leeson, Joseph Ciarrochi, Patrick C.L. HeavenDocument6 pagesPersonality and Individual Differences: Peter Leeson, Joseph Ciarrochi, Patrick C.L. HeavenDanielle DaniNo ratings yet

- Understanding Shift in StudentDocument26 pagesUnderstanding Shift in StudenthqwarzenNo ratings yet

- Student Perception of TeacherDocument8 pagesStudent Perception of Teacherrifqi235No ratings yet

- 12X PDFDocument19 pages12X PDFChintia Meliana Kathy SiraitNo ratings yet

- Effect of Stress On Academic Performance of StudentsDocument32 pagesEffect of Stress On Academic Performance of StudentsAnonymous mtE8wnTfz100% (1)

- Haimovitz Dweck - 17 - MindsetsDocument12 pagesHaimovitz Dweck - 17 - MindsetsDaniela VerissimoNo ratings yet

- Student-Related Variables As Predictors of Academic Achievement Among Some Undergraduate Psychology Students in BarbadosDocument10 pagesStudent-Related Variables As Predictors of Academic Achievement Among Some Undergraduate Psychology Students in BarbadosCoordinacionPsicologiaVizcayaGuaymasNo ratings yet

- Parents Role in Student MotivationDocument12 pagesParents Role in Student Motivationapi-289583463No ratings yet

- Effects of Family Functioning and Family Hardiness On Self-Efficacy Among College StudentsDocument9 pagesEffects of Family Functioning and Family Hardiness On Self-Efficacy Among College StudentsSunway UniversityNo ratings yet

- Karaman 2017Document11 pagesKaraman 2017AUFA DIAZ CAMARANo ratings yet

- JPSP 2022 010Document10 pagesJPSP 2022 010Rhianne AngelesNo ratings yet

- Yoko Na Mag-Aral Rrs PiDocument3 pagesYoko Na Mag-Aral Rrs PiSecret TintNo ratings yet

- NothingDocument20 pagesNothingmarcoensomo29No ratings yet

- Autonomy, Belongingness, and Engagement in School As Contributors To Adolescent Psychological Well-BeingDocument12 pagesAutonomy, Belongingness, and Engagement in School As Contributors To Adolescent Psychological Well-BeingHiền Mai NguyễnNo ratings yet

- EJ1067053Document8 pagesEJ1067053Rue RyuuNo ratings yet

- Final Qualitative PaperDocument19 pagesFinal Qualitative Paperapi-293221695No ratings yet

- Personality Triats and Self Esteen On Interpersonal Dependence 2022Document54 pagesPersonality Triats and Self Esteen On Interpersonal Dependence 2022Alozie PrestigeNo ratings yet

- Lounsbury 2005Document15 pagesLounsbury 2005Lyli AnhNo ratings yet

- Prediction of School Performance: The Role of Motivational Orientation and Classroom EnvironmentDocument5 pagesPrediction of School Performance: The Role of Motivational Orientation and Classroom EnvironmentAdina NeaguNo ratings yet

- Self-Esteem of The Students Od DJCNHSDocument32 pagesSelf-Esteem of The Students Od DJCNHSAprilgene RagantaNo ratings yet

- PARENTINGTAE2 1newDocument48 pagesPARENTINGTAE2 1newAngel Beluso DumotNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Academic Pressure On Students Well BeingDocument45 pagesThe Impact of Academic Pressure On Students Well BeingKrean DaleNo ratings yet

- The Anti LiberalismDocument38 pagesThe Anti Liberalismronilolomocso017No ratings yet

- Relaciones Con La Salud Mental y El Funcionamiento Académico en Estudiantes Chinos de Escuela Primaria (2021)Document13 pagesRelaciones Con La Salud Mental y El Funcionamiento Académico en Estudiantes Chinos de Escuela Primaria (2021)Catalina Muñoz MonteroNo ratings yet

- Relationship Among Family Support, Love Attitude, and Well-Being of Junior High School StudentsDocument8 pagesRelationship Among Family Support, Love Attitude, and Well-Being of Junior High School StudentsLeigh YaNo ratings yet

- Fan, 2014 PDFDocument18 pagesFan, 2014 PDFMarco Adrian Criollo ArmijosNo ratings yet

- Bab I Bilangan Bulat Dan Bilangan PecahanDocument16 pagesBab I Bilangan Bulat Dan Bilangan PecahanMangGun-gunGunawanNo ratings yet

- 2017 Rzlnce, SDTDocument15 pages2017 Rzlnce, SDTShahzad AliNo ratings yet

- Children's Achievement Motivation in School: January 2015Document25 pagesChildren's Achievement Motivation in School: January 2015RadYanNo ratings yet

- v1 Issue1 Article5Document14 pagesv1 Issue1 Article5Queenemitchfe PulgadoNo ratings yet

- The Influence of EmotionalDocument10 pagesThe Influence of EmotionalJesus Felipe Quintero LopezNo ratings yet

- Harter, 1988Document8 pagesHarter, 1988Coney Rose Bal-otNo ratings yet

- Social Emotional Learning in ELT Classrooms: Theoretical Foundations, Benefits, Implementation, and ChallengesDocument9 pagesSocial Emotional Learning in ELT Classrooms: Theoretical Foundations, Benefits, Implementation, and ChallengesAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Self-Perception Profile For Adolescents: Harter, 1988 Facio Et Al., 2006Document3 pagesSelf-Perception Profile For Adolescents: Harter, 1988 Facio Et Al., 2006KATO MBALIRENo ratings yet

- Evidence Base Update For Parenting Stress Measures in Clinical SamplesDocument22 pagesEvidence Base Update For Parenting Stress Measures in Clinical SamplesCorina NichiforNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Professional Commitment PDFDocument18 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Professional Commitment PDFMochmamad LuthfiNo ratings yet

- Mental Health ResearchDocument6 pagesMental Health ResearchArianna KelawalaNo ratings yet

- Self-Stigma, Mental Health Literacy, and Attitudes Toward Seeking Psychological HelpDocument11 pagesSelf-Stigma, Mental Health Literacy, and Attitudes Toward Seeking Psychological HelpNatalia RamirezNo ratings yet

- Promoting Early Adolescents' Achievement and Peer RelationshipsThe Effects of Cooperative, Competitive, and Indi Vidualistic Goal ST RucturesDocument24 pagesPromoting Early Adolescents' Achievement and Peer RelationshipsThe Effects of Cooperative, Competitive, and Indi Vidualistic Goal ST RucturesVo PeaceNo ratings yet

- Art I Colostrum Ent OlhDocument19 pagesArt I Colostrum Ent Olhgoxenan296No ratings yet

- Parental Autonomy Support and Career Well-Being Mediated by Perceived Academic Competence and Volitional AutonomyDocument16 pagesParental Autonomy Support and Career Well-Being Mediated by Perceived Academic Competence and Volitional AutonomysyahrilNo ratings yet

- Help-Seeking and Helping Behavior in Children As A Function of Psychosocial CompetenceDocument13 pagesHelp-Seeking and Helping Behavior in Children As A Function of Psychosocial CompetenceManal ChennoufNo ratings yet

- Brooks HighSchoolExperiences v.01Document19 pagesBrooks HighSchoolExperiences v.01Vaida Andrei OrnamentNo ratings yet

- heaven2008Document18 pagesheaven2008bihc13No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document6 pagesChapter 2Frustrated LearnerNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Academic Self Efficacy of StudentsDocument39 pagesEvaluation of The Academic Self Efficacy of Studentsrhea parajesNo ratings yet

- Uas Abstract PGSDDocument16 pagesUas Abstract PGSDhaerul padliNo ratings yet

- 2016 - CtiDocument13 pages2016 - CtiSITI NUR HAZWANI BINTI RAHIMNo ratings yet

- Format For Field Methods ResearchDocument12 pagesFormat For Field Methods ResearchKimberly NogaloNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Stress Among Faculty Members ofDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Stress Among Faculty Members ofMichevelli RiveraNo ratings yet

- Optimism Vs Academic Performance: A Correlational StudyDocument16 pagesOptimism Vs Academic Performance: A Correlational StudyNA RANo ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Study of CaDocument15 pagesA Phenomenological Study of CaWiyar HoldingNo ratings yet

- Artikel KerjayaDocument15 pagesArtikel KerjayaPuneswary RamesNo ratings yet

- Modelo de Artículo ApaDocument31 pagesModelo de Artículo ApaHugo González AguilarNo ratings yet

- Capstone Research Final PaperDocument17 pagesCapstone Research Final Paperapi-642548543No ratings yet

- Foreign Literatures: Deb, S., Strodl, E., & Sun, H. 2015)Document10 pagesForeign Literatures: Deb, S., Strodl, E., & Sun, H. 2015)Rose ann BulalacaoNo ratings yet

- Stressors Among Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Pandemic LearningDocument21 pagesStressors Among Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Pandemic LearningEllaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 8 An Ionic Equation For The Formation of Lead (II) IodideDocument3 pagesWorksheet 8 An Ionic Equation For The Formation of Lead (II) IodideNovah Guruloo0% (1)

- The Effect of Occupational Health and Safety Practices Onorganizational Productivity A Case of Mumias Sugar Company in KenyaDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Occupational Health and Safety Practices Onorganizational Productivity A Case of Mumias Sugar Company in Kenyainventionjournals0% (1)

- Lean Six Sigma Black Belt Project For Supply Chain: Dock-to-Stock Part of Customer Supply ChainDocument7 pagesLean Six Sigma Black Belt Project For Supply Chain: Dock-to-Stock Part of Customer Supply ChainAmit AnandNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Data - Unit III (New)Document90 pagesAnalysis of Data - Unit III (New)Ashi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Practical Research 2 Quantitative Design: Prepared By: J-B Vincent L. RicoDocument58 pagesWelcome To Practical Research 2 Quantitative Design: Prepared By: J-B Vincent L. RicoRoma MalasarteNo ratings yet

- Mca4020 SLM Unit 11Document23 pagesMca4020 SLM Unit 11AppTest PINo ratings yet

- DLL SIR DAVIDapplied Economic - Oct. 02 - 06, 2017Document10 pagesDLL SIR DAVIDapplied Economic - Oct. 02 - 06, 2017Rossano DavidNo ratings yet

- 2008 Homburg, Jensen & Krohmer - Configurations of Marketing and Sales - A Taxonomy (DV) PDFDocument24 pages2008 Homburg, Jensen & Krohmer - Configurations of Marketing and Sales - A Taxonomy (DV) PDFkeku091No ratings yet

- Impact of Packaging On Consumers' Buying Behaviour:: A Case Study of Mother Dairy, KolkataDocument7 pagesImpact of Packaging On Consumers' Buying Behaviour:: A Case Study of Mother Dairy, KolkataMJoyce Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Geotechnical ProposalDocument4 pagesGeotechnical ProposalAivan Dredd PunzalanNo ratings yet

- Environmental Monitoring Report: - March 2020Document180 pagesEnvironmental Monitoring Report: - March 2020zhou jieNo ratings yet

- PR 1 DLPDocument3 pagesPR 1 DLPRubenNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper SampleDocument8 pagesConcept Paper Samplejhon rey batistisNo ratings yet

- Resistive Network AnalysisDocument27 pagesResistive Network AnalysisTanmaysainiNo ratings yet

- Principles of Marketing 1 Page SyllabusDocument2 pagesPrinciples of Marketing 1 Page SyllabusMarl Dominick G. AquinoNo ratings yet

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of First Order Factor Measurement Model-ICT Empowerment in NigeriaDocument8 pagesConfirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of First Order Factor Measurement Model-ICT Empowerment in NigeriazainidaNo ratings yet

- Sample Respondents of The StudyDocument2 pagesSample Respondents of The StudyMichael Qoi Laguilay40% (5)

- Solutions - December 2013Document3 pagesSolutions - December 2013Nurul SyafiqahNo ratings yet

- Week 3 Standard Consistency, Setting Time & Fineness of CementDocument6 pagesWeek 3 Standard Consistency, Setting Time & Fineness of CementFareez SedakaNo ratings yet

- Bhargav EeDocument103 pagesBhargav EesatheeshNo ratings yet

- Activity-Based Costing How Far Have We Come InternationallyDocument7 pagesActivity-Based Costing How Far Have We Come Internationallyapi-3709659No ratings yet

- Walkability ResearchDocument62 pagesWalkability ResearchMinSyn LimNo ratings yet

- Week5Assignment - Lima-Gonzalez, C. (Extension)Document7 pagesWeek5Assignment - Lima-Gonzalez, C. (Extension)Constance Lima-gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Impact of External Recommendations on Cement Purchase DecisionsDocument11 pagesImpact of External Recommendations on Cement Purchase Decisionsshiv sharan patelNo ratings yet

- Van Brakel Measuring StigmaDocument12 pagesVan Brakel Measuring StigmaKaterinaStergiouliNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning HandbookDocument50 pagesStrategic Planning Handbookrony_phNo ratings yet

- Bindura University of Science EducationDocument20 pagesBindura University of Science EducationNaison Shingirai PfavayiNo ratings yet

- Minro Mag Ram M22 LD-signedDocument1 pageMinro Mag Ram M22 LD-signedNookang SeaSunNo ratings yet

- GED 321 - TASK 1 - 21 Century Assessment Mind MapDocument1 pageGED 321 - TASK 1 - 21 Century Assessment Mind MapArcyRivera100% (1)