Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Akerlof 1969

Uploaded by

biblioteca economicaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Akerlof 1969

Uploaded by

biblioteca economicaCopyright:

Available Formats

Relative Wages and the Rate of Inflation

Author(s): George A. Akerlof

Source: The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 83, No. 3 (Aug., 1969), pp. 353-374

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1880526 .

Accessed: 17/06/2014 05:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Quarterly

Journal of Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

QUARTERLYJOURNAL

OF ECONOMICS

Vol. LXXXIII August 1969 No. 3

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION*

GEORGE A. AKERLOF

I. Introduction, 353.-II. A price-price inflation, 355.-III. A wage-wage

inflation, 363.- IV. Spontaneous inflations and general equilibrium, 371.- V.

Conclusions, 373.

Monetary theory in the post-Keynesian era has, to a good ex-

tent, centered around the question "is money neutral?" This is an

important question, of course, because the existence of such eco-

nomic animals as the Phillips Curve may well depend on the answer.

Patinkin's famous book argues for the neutrality of money: with

different levels of the money supply in a perfectly competitive

world all equilibrium real variables will be the same.' Naturally in

such a world the Phillips Curve cannot exist, but, as Patinkin him-

self writes, this is more a matter of definition than of empirical

fact -for, in the long run, irrespective of the money supply (or

its rate of increase), equilibrium is approached; and by definition

this equilibrium precludes unemployment.

The question which presents itself is whether Patinkin's results

generalize to a world which has "stickiness" and various "market

imperfections." Friedman, in his American Economic Association

Presidential address, has asserted that it does: the long-run level of

* The author would like to thank Bent Hansen, Stephen A. Marglin,

William Nordhaus, Albert Fishlow, Giorgio La Malfa and Bagieha Minhas for

valuable comments and the Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi for finan-

cial support. All mistakes. however. belong to the author.

1. D. Patinkin, Money, Interest and Prices (2d ed.; New York: Harper

and Row, 1965). It should be stated at the outset that the models here at-

tempt an argument essentially different from the Tobin and Gurley-Shaw

portfolio balance type of argument. For this reason the portfolio, or capital

investment, decision is intentionally ignored. J. Tobin, "Money and Eco-

nomic Growth," Econometrica, Vol. 33 (Oct. 1965); and J. G. Gurley and E.

S. Shaw, Money in a Theory of Finance (Washington: Brookings Institution,

1960).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

354 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

unemployment, irrespective of market structure, stickinesses, etc.,

will be independent of the long-run rate of increase of the money

supply.2 For, his argument goes, in the long run if a given rate of

inflation is universally expected, all persons will hedge against this

rate of inflation -and since all bargains are rationally decided by

real considerations, real transactions (excluding capital formation)

will take place as if this rate of inflation did not exist. At first glance

Friedman's argument appears perfectly general: but the question

remains whether Friedman's logic is still valid if contracts are made

according to real considerations, but for the duration of the contract

some price variables remain fixed in money terms. The obvious ex-

ample of such an institution is the union wage bargain with both

the union and management aware of the "real" aspects of the bar-

gain - but with the form of contract restricted so that money wages

change at only yearly intervals.3

It is quite clear from all historical accounts of hyperinflation

that such fixed-money contracts break down as the rate of inflation

becomes large.4 But for the usual Phillips-Curve watcher such cases

of hyperinflation are not in the relevant range: rather the question

is whether some "moderate" rate of inflation (say 2 or 3 per cent per

annum) is better than none at all.5 In this range, given the con-

venience of fixed-money contracts - one of the major reasons it-

self for the policy goal of price stability - it is not unreasonable

to expect the form of contract to remain unchanged.6

Of course, it is easy to show the existence and nature of a short-

run Phillips Curve with fixed expectations about the future rate of

inflation. In the long run if expectations about the rate of inflation

are actually realized, the Phillips Curve is far more restricted; but

in the models below there is an interpretation whereby such a

Phillips Curve exists and the neutrality of money, in turn, is false.7

2. M. Friedman, "The Role of Monetary Policy," American Economic

Review, LVIII (Mar. 1968), 7-10. Lindahl foresaw Friedman's argument

thirty years ago: ". . . anticipated changes in the price level have no eco-

nomic relevance, since they neither influence the relative prices of factors

of production and consumption goods, nor the extent and direction of pro-

duction." E. Lindahl, Studies in the Theory of Money and Capital (London:

Allen and Unwin, 1939), p. 148.

3. The models presented must be slightly altered to include "wage drift."

4. In particular see C. Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1937).

5. A. W. Phillips, "The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate

of Inflation in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957," Economica, N.S. XXV (Nov.

1958).

6. An excellent justification for the convenience of temporarily fixed

prices is given by 0. Eckstein and G. Fromm, "The Price Equation," Ameri-

can Economic Review, LVIII (Dec. 1968), 1159-60.

7. Many besides Friedman have wondered about the relation between

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 355

II

The specific view of the economy which underlies this paper

is that of Triffin's Monopolistic Competition and General Equilib-

rium Theory.8 The economy, as pictured, consists of many monop-

olists who all compete for a given total level of demand (which is

in turn correlated with the level of employment). Perhaps the best

way to view the meaning of this model is that the producers in each

oligopolistic industry reach a pricing decision not far from the de-

cision that would be reached if the industry were in fact a monopoly.

(This process is not dissimilar to what Professor Fellner describes in

Competition Among the Few.)9 In turn these industries (acting as

monopolies) compete amongst themselves in a Chamberlinian fash-

ion for a fixed level of real aggregate demand.

The natural worry, of course, is that the problem of oligopolistic

interdependence has been seriously ignored; but this would be a mis-

understanding of the spirit of the argument. Rather monopolistic

competition is quite naturally chosen as the simplest example of the

imperfect (and interdependent) world we wish to picture - and any

of the other classical bargaining solutions might give different re-

sults algebraically - but would give the same results qualitatively.

Also, Chamberlinian independence is undoubtedly a bad model for

the behavior of large firms in many industries; but, on the contrary,

it may be a good description of interindustry pricing behavior. As

Triffin points out cotton textiles and automobiles may compete as

much for a consumer dollar as any two types of cloth or any two

types of automobile; but it is also implausible that the automobile

manufacturers and the textile producers take account of the mu-

tual interdependence of their pricing decisions.

In this spirit an economy is pictured with only two firms (where

this small number of firms is an abstraction of some true multidi-

mensional many-unit economy). And in accord with monopolistic

competition theory each firm (or industry) chooses a price level

such that marginal cost equals marginal revenue - without taking

the other firm's reaction into account. But there is nothing inherent

in the approach (except perhaps a desire for algebraic simplic-

the long-run and the short-run Phillips Curve. See especially, R. G. Lipsey,

"The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money

Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957: A Further Analysis," Eco-

nomica, N.S. XXVII, 1960; and E. Kuh, "A Productivity Theory of Wage

Levels -an Alternative to the Phillips Curve," Review of Economic Studies,

XXXIV (Oct. 1967).

8. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1940.

9. New York: Knopf, 1949.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

356 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

ity) which dictates this particularsolutionto the oligopolyproblem.

To give the demandcurvesform and substancelet

(1) DI=a-P1/P2

and let D2 be, symmetrically,

(2) D2= a-P1/P2

whereD and p are demandand prices,wheresubscriptsone and two

refer to firms one and two, and where a is a parameter. If Pi = P2,

D= = a-1. In Chamberlinianlanguage the "dd" curves of

firm one are the demand curves with P2 fixed. And the "DD"

curve with P1=P2 is a vertical line. The parametera, accordingly

correspondsto the level of total output, which is close to the level

2a-2. These demandcurves are slightly less than ideal for several

reasons. (1) Ideally, the demand curves for the two firms should

add up to some given constant irrespectiveof relative prices. But

the simplificationin algebra made possible by (1) and (2) should

justify their choice- at least for expository purposes. It should

also be noticed that in the neighborhoodof P1/P2=1, D1+D2 =

2a-2, up to second order. (2) An argumentis also necessary to

justify the use of a as a parameter. If the demand curves were

written more generally

(1') D1=a-bpl/p2

and

(2') D2= a- bp2/p1

all solutions would depend on the value of a/b -or a parameter

which reflectsthe elasticity of demand. On the other hand, it makes

sense to vary a as a proxy to reflectwhat is happeningin another

part of the market: as full employmentis approachedthere is a

decreasein the elasticity of supply of labor. In the exampleused in

this section, marginalcosts are assumedto be zero, to simplify the

mathematics. In the next section the supply variable is given the

wrong dimensionality (again to simplify the mathematics)- but

the artificialdevice of varying a relative to b gives qualitatively the

same results as changingthe supply elasticities. A later footnote

justifies this procedurerigorously.

Judgment is suspended (until later) about the determinants

of a; but two commentsmust be made now. First of all, a, which

correspondsto the level of aggregatedemand,is considereda param-

eter which is, in turn, controlled by the governmental controls

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 357

of monetary and fiscal policy. Second, quite clearly this is a

closed economy - for otherwise a third "firm" must be added whose

pricing behavior is exogenously given. For this reason alone the

model described would be a much better picture of the American

economy, for example, than of the British.

To continue, the model assumes that firms operate in the

following way; they are Chamberlinian monopolistic competitors.

That means that each firm sets its price so that MR= MC, where

marginal revenue represents the change in revenue from selling an

additional unit of output -if the competitor leaves his price un-

changed. It should be emphasized here, as in the next section, that

this particular assumption is not in any way essential to the overall

point of view.

Temporarily it is assumed that neither firm one nor firm two

has any variable costs (or that MC equals zero for both firms). As

such this section should be considered a finger exercise for the in-

creasingly complex models of later sections.

The second important element of the model is the nonsyn-

chronization of pricing decisions by firms one and two. By this it

is meant that firm one makes a pricing decision each January and

firm two makes a pricing decision each July. It is also an important

feature of the model that these prices remain constant throughout

the year. Measuring time in half-years, firm one makes its price

decisions at even times 2t, and firm two makes its pricing decisions

at odd times 2t+1, and

(3) P1, 2t=P1, 2t+1

(4) P2, 2t+1 = P2, 2t+2.

This constancy of money prices over a two-period interval is the

major feature which differentiates our thinking from Friedman's.'

The justification for this assumption is that it does describe a real-

world form of market imperfection. This assumption becomes con-

siderably more realistic in the next section where the "price-vari-

ables" which are yearly constant are money wages instead of goods

prices.

Firms one and two have symmetric demand curves and bargains

are made in real terms; with the same expectations about the rate

of inflation and a given level of aggregate demand, firm one's view

of the world at even times will correspond exactly to firm two's

view of the world at odd times. As a result -which can be rigor-

1. Friedman, op. cit.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

358 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

ously proved - firm one at even times will have exactly the same

real possibilities as firm two at odd times. And the relative price

chosen determines the point attained. As a result, the relative price

chosen by firm one at even times will be the same as the relative

price chosen by firm two at odd times.

At this point, since the model is nearly complete, it is worth-

while to pause and summarize the assumptions already made: (A)

There are just two firms. (B) Demands are given by (1) and (2).

(C) Each firm sets a price once a year, equations (3) and (4). (D)

In setting this price each firm maximizes its expected profits over the

two-period interval for which this price will be maintained. It

fails, however, to take account of the reaction of the other firm in

the next period. (E) At least temporarily, the marginal cost of each

firm is zero.

The two assumptions of nonsynchronization and the symmetry

of the relative pricing decisions can be coupled together:

by the symmetry of (1) and (2) and with identical cost curves

and expectations about the rate of inflation,

Pl, 2t P2, 2t+1 Pl, 2t+2

(5) - ==

P2, 2t Pl, 2t+1 P2, 2t+2

and together with (3) and (4)

P 2t+ P2 2t+1 P2t+2 by (5)

Pl, 2t+1

= P2, 2t+1 P2, 2t+l by (4)

Pl, 2t+1

Pi, 2t

P22t+1 by (5)

P2, 2t

= ( P',2t

P2, 2t

) Pl,2t+1 by (5)

( P122t) Pl,2t by (3)

or, rewriting:

(6) P1, 2t+2 (Ply 2t )2

P22 2t P22 2t

Prices rise over the year by a multiple equal to (Pip 2t). Relative

prices determine this rate of inflation.2

2. Similar equations can be derived if the demands for firms one and

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THIE RATE OF INFLATION 359

Equation (6) occasions some remarks. It should be clear that

it is independent of the particular market behavior: it depends only

on symmetry and nonsynchronization. Equation (6) should also

make clear that the assumptions both of nonsynchronization and

of noncompetitive markets are necessary (as well as sufficient) for

this view of inflation.

For nonsynchronization allows the economy to depart from

static equilibrium at all times: in this economy firms one and two

can only be simultaneously satisfied if the rate of inflation is zero.

Later it will be shown that the desired relative price (P1/P2) de-

pends on the level of aggregate demand. In the normal case there

is only one level of aggregate demand for which the desired relative

price is equal to one. Without nonsynchronization any other level

of aggregate demand is incompatible with equilibrium - because

PI/P2 and P2/P1 cannot both simultaneously attain their "desired"

values. The level of output for which the desired relative price is

one therefore corresponds to Friedman's long-run equilibrium.

The dynamics of this assertion demand a sneak preview of

what follows. In Friedman's dynamics, with a given money supply

or rate of growth of the money supply, if the desired relative price

is larger than one, prices will rise sufficiently to reduce real balances

and therefore aggregate demand - and vice versa if the desired

relative price is less than one. Friedman's system does not allow-

which nonsynchronization does allow - a continued dynamic ten-

sion so that relative prices never fully adjust. This is discussed

further in Section IV below.

Equation (6) should also make clear the importance of noncom-

petitive markets. If monopoly power is unimportant, in the presence

of unused resources the relative price set by each decision-maker

will be very low; with the full use of resources the relative price

set by each decision-maker would be high. Thus large changes in

the rate of inflation result from small changes in aggregate demand.

In the limit this corresponds to the traditional quantity theory

point of view.

Returning to the specific model of monopolistic competition

and to the demand curves (1) and (2) allows an exact evaluation

of the inflationary process. As a Chamberlinian monopolistic com-

petitor, each January the manager of firm one sets the price of the

good produced by firm one to maximize revenue for the whole year.

There will be some slight differences of behavior if revenue is dis-

two are not symmetrical and also if the expectations of firms one and two are

different.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

360 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

counted by a rate of return or the rate of inflation. For the sake

of exposition we shall assume for the moment that the revenue

maximized is undiscounted.

Revenue is Pl, 2t D1i 2t+Pl 2t+1 DI) 2t+i. D1, 2t+1 depends, how-

ever, on the unknown price charged by firm two at time 2t+1. But

suppose that firm one expects this price to rise by a multiple (ye) 2,

or that

Pe2,2t+I=7e2P2,2t (where "e" refers to "expected"). In this

case expected revenue Re will be:

Re= Pi, 2t (a- P, 2t' +Pl,

P2, 2t

2t+1 (a-Pi 2t+-)

')2+

Py

=P1, 2t a- +P2t a- 2t)

Given these expectations firm one chooses pI, 2t to maximize Re. Be-

ing a monopolistic competitor he maximizes Re with respect to PI

as if P2 were independent of his choice of pi. This yields the condi-

tion that

Pl, 2t aye2

P2, 2t 1+ye

If firm two has the same expectations as firm one about the rate of

inflation, by (6),

(7) yA = a

(7) y +ye

where (7A) 2 represents the yearly multiple of price change.

Equation (7) gives the actual rate of inflation as a function of

the level of aggregate demand and the expected rate of inflation.

With given expectations this could be considered a short-run Phillips

Curve.

In the long run, however, according to Friedman's argument the

expected and the actual rates of inflation should coincide.3 In func-

tional notation this gives two equilibrium conditions

(8) yA= F (a,ye)

(9) yA=7e

or, rewriting, in equilibrium

(10) y=F(a, y),

where y denotes an equilibrium rate of inflation.

3. Friedman, op. cit.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 361

The natural question is whether there is a unique y = y (a) for

each level of aggregate demand a. Such a function would correspond,

of course, to a long-run Phillips Curve.

With only static considerations, there is no such unique y which

can be associated with each a. For a >2 the solutions of (10) are

a=' (a2- 4)/2

y=O, andy= 2 Fora=2thesolutionsarey=Oandy=1;

and for a <2 the only real solution is y=0.

Considering a >2, there is some reason for choosing the upper

roots as the end result of the process described. Figure I graphs 7A

as a function of ye. It is seen that with static expectations, 0 and

(a+ (a2-4)/2) /2 are stable roots (follow the zigzags in Figure I).

rA

/a a2

I+

+r2

Stable

Unstable

Stable re

FIGUREI

Startingwith nondeflationarybut static expectationsabout the

rate of inflation, with a >2, the upper root will be approached.

Choosingthis root as "the solution"then

(11) /= (a+ (a2 -4)1/2)/2 a>2

and dy/da =l/2(1+a/(a2- 4)?2) > 0; or, the long-runequilibriumof

the economy given an initial condition of nondeflationaryexpecta-

tions, is an increasingfunction of the level of overall aggregatede-

mand. With the restrictionsmentionedand the appropriatequali-

fications (11) can be taken as a long-runPhillips Curve.

While the theory laid down is satisfactory in this stability of

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

362 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

the upper roots -and the consequent gravitation toward these

upper roots with initial nondeflationary expectations, one fact is

particularly unsettling. The double roots are inherent in the prob-

lem and depend on the specific nature of neither the cost nor the

demand functions. And if y= 1 is a solution of system (8) and (9),

it will also be a double root. This can be shown formally -but a

heuristic argument clarifies the reason for this happening.

The profit-maximizer controlling firm one chooses a relative

price x to maximize the sum of its profits in both the early and the

later periods. In the noninflationary case the relative price which

maximizes profits in the first period and in the second period are

exactly the same. With an expected (nonzero) rate of inflation, how-

ever, there is a conflict between maximizing profits in the first and in

the second periods. If x1 is the profit-maximizing relative price

in the first period, then Xlye2 is the profit-maximizing relative price

in the second period. Since the demand functions are second dif-

ferentiable and the same weight is placed on both the first and second

period, the profit-maximizing solution is approximately (up to

second order) to let x be the average of these two relative prices.

Therefore, in the neighborhood of x= 1,

1+ye2

x= 27 2 with the result that

dx

dye l.

At the same time this shows the natural way to elude the

double-rootedness problem. A high rate of time discount, which

causes the decision-maker to place a low weight on the second

period, reduces dx/dye and can lead to single-solution results with all

the desirable properties. Clearly this is the case in the limit where

only the early period is considered and

ye = yA = pi/p2 = a/2.

The next step is to add money to the system. This is done in

the simplest way. The parameter a, or real demand, is associated

with real balances. Suppose that a= g (M/p), or that a is function-

ally dependent on real balances.

There is a slight problem of representing real balances in our

model, because "the price level" is well defined only if Pi equals

P2. Therefore real balances are not uniquely well defined. There

is the further problem that it is unreasonable to assume that an in-

dividual firm considers the effect of its price decision on the level

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 363

of real balances. All of this suggests that in constructing an ex-

ample needless complication will be avoided if the demand curve

for firm one depends upon M/p2, where P2 is interpreted as the price

level of "other" goods and similarly the demand curve for firm two

should depend on M/pl. In this spirit let:

_i=M Pi

P2 P2

M P2

Pi Pi

Further suppose that the nominal money supply is increasing at a

positive rate A. Given initial nondeflationary price expectations,

and, initially M/p2 and M/pl > 2, an equilibrium will be approached

with A equal to the rate of inflation. For suppose that Pi and P2 are

increasing at a rate less than A, then according to the previous argu-

ment a will increase, and therefore the rate of inflation. Similarly

if Pi and P2 are increasing at a rate greater than A, real balances

(or a) will be decreasing.

As a consequence, in the long run prices and the money supply

will be increasing at the same rate. The rate of increase of the

money supply determines the level of real balances so that prices

and the money supply are increasing at the same rate. The rate

of increase of the money supply therefore determines the long-run

level of real balances and of real activity.

III

From the last section we preserve the assumption that there

are just two firms which act as monopolistic competitors in dividing

up a total aggregate demand-and that the demand curves for

firms one and two are given by equations (1) and (2) respectively.

But other assumptions are changed: First, the prices of goods

are free to adjust in each period. But money wages, in contrast,

must remain fixed throughout the year. Second, each firm is given

a simple production function-but third, the nature of the wage-

bargain must be specified (and therefore given restrictive form).

Finally, the framework of this section, being less restrictive, allows

easy modification to solve the problem of the dimensionality of a.

To begin, it is assumed that the short-run production function

of each firm is

Qi =El

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

364 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

or, output of each firm is proportional to its employment.

The cost function of each firm can be specified then:

C1= w1Qi

C2 = W2Q2;

or the cost of production for each firm is the wage rate of its work-

ers times the level of output.

A bit of algebra shows that if marginal revenue equals marginal

cost

(a-2D,)p2=wi

(a-2D2)p1 =w2

or, equivalently,

pi = 1/2 (ap,2+wl)

p2 =1/2 (api+W2)

Countervailing the oligopoly power of the firms, we picture

yearly bargains made between unions and employers. The best

justification for this kind of bargaining solution is a desire to in-

corporate some elements of Professor Galbraith's theory.4

But different structures, closer to perfect competition, could

yield similar results. Specifically in mind are Becker's comments

about the returns to specific training costs.5 It is clear from his

argument that the division of the returns to specific training costs,

by their nature, involves some sort of bargaining between the em-

ployer and the employee. Also several empirical studies of "learn-

ing-by-doing" in specialized tasks give some evidence -although

the connection is not necessary -for the importance of specific

training."

In our particular model there are just two unions: the union

which deals with firm one and the union which deals with firm two.

Bargaining occurs yearly -and once a year a money wage is set:

this money wage is constant throughout the year. Bargaining for

union one occurs every January. Bargaining for the second union

occurs every July. Again measuring time in half years, the bar-

gaining between firm one and its union occurs at times 2t (for in-

4. J. K. Galbraith, American Capitalism, The Concept of Countervailing

Power (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1952).

5. G. S. Becker, Human Capital (New York and London: Columbia

University Press, 1964).

6. See references given by K. J. Arrow, "The Economic Implications

of Learning by Doing," Review of Economic Studies, XXIX (June 1962) and

also S. Hollander, The Sources of Increased Efficiency: A Study of du Pont

Rayon Plants (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1965).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 365

tegers t); and bargaining for union two occurs at times 2t+1 (for

integers t).

One simple example of the union-employer bargaining process

is given as follows. Each union realizes that higher wages induce

higher prices in its own industry. In turn higher prices lead to less

demand and therefore less employment. High wages consequently

induce high unemployment rates for the given union; low wages

mean the opposite. Thus there may be some level of wages (neither

o nor oo) which maximizes total union income. Each union, we

say, wishes to maximize its money income over the coming year.

(This is based on a model of union behavior suggested by John

Dunlop.) 7 The union demands that wage which it thinks will

maximize its money income. The firms accede to these demands.

Again, it is important to emphasize that the exact nature of the

bargaining solution is not important in the phenomenon described.

A similar model is given by assuming that each union maximizes

a() E+ (1 - a ) XwE

P

or that the union maximizes some function of employment and real

income. As employment rises (or as u the unemployment rate falls)

the weight on real income rises. This formulation solves the prob-

lem of the artificial nature of the parameter a: we can assume a

constant but that a varies with the level of aggregate demand. But

another, probably less serious, problem occurs. Since there are

two goods, the price level p is not well defined; some device for

defining p in terms of p, and P2 is needed before a Phillips Curve can

be derived.

In the text, however, the original model will be assumed: union

one then wishes to maximize wl, 2t E1, 2t+W1, 2t E1, 2t+1 where the

period 2t represents periods from January to July and 2t+1 repre-

sents periods from July to January.

Exactly the same problems with the expected and actual rates

of inflation occur in the more complex model here that occurred in

the last section (and exactly the same analysis can be used). If

union one expects P2, 2t+1 to be higher by a multiple ye, then

Ee, 2t+1 = 1/2 (a-W 2t+1

<x-_ e2,2)

= 1/2 a

W1, 2t)

vYeP2sok

7. J. T. Dunlop, Wage Determination Under Trade Unions (New York:

Macmillan, 1944), Chap. III.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

366 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

(where e refers to "expected")

and union one chooses its wage to maximize

WI, 2t E1, 2t+Wl, 2t+1 Eel, 2t+1, or,

using calculus,

WI, 2t aye

P2, 2t 1+Ye

(The difference in ye between here and Section II may be noted;

this is only a matter of notational convenience).

Also there is an analogue of equation (6). Because of the

rationality of economic agents and because the economy is closed,

all bargains will occur in real terms, and it can be asserted that

W1, 2t=f (P1 2t, P2, 2t, W2, 2t; ye, a)

Pl, 2t =q (P2, 2t Wl, 2t, W2, 2t; ye, a)

P22 2t= h (Pi, 2t, W1, 2t, W2, 2t; ye, a).

With a given expected rate of price increase, and a given level of

aggregate demand, the price of each good or factor (subject to

change at a given time) is a linear-homogeneous function of the

prices of all other goods and factors.

With W2,2t fixed there are three equations and three unknowns.

Because all three equations are homogeneous of degree one (in the

goods and factor prices), if (Pol, 2t, P02, 2t, W01,2t) is a solution with

W2, 2t==W02, 2t, then (Ap01,2t, AP02, 2t, AW01,2t) is a solution with

W2,2t = AW02t, 2t. Therefore,if there is a uniquesolutionof these equa-

tions for given ye, a and W2, 2t,

WI;,2t ye 2a) .

2

W2, 2t

Symmetry dictates with constant ye that:

WI, 2t W2, 2t+1 W1, 2t+2

W2) 2t W1, 2t+1 W2, 2t+2

Combined with nonsynchronization

(12) W1, 2t+2 (Wit 2t )2

Wi, 2t W2, 2t

But also P 2t+2 W1, 2t+2 and therefore the rate of inflation

Pl, 2t Wl, 2t

is given by the relative desired wages of the various labor groups.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 367

This is exactly analogous, of course, to the results of the last sec-

tion.

Also equation (12) is the justification for the title of this

paper: the relative wages of labor groups one and two determine the

rate of inflation. It should also be mentioned that the wage bar-

gains pictured here correspond closely to the wage determination

process of The General Theory. At the time when each labor group

makes its bargain in The General Theory it is either restrained or

empowered by the at-least temporary fixity of the wages of other

labor groups. Keynes's system of bargaining (which is also his

reason for the "constancy" of the money wage) is much akin to the

nonsynchronized procedures assumed here.8

There has been some discussion in the literature on inflation

of "leapfrogging," alias "the wage-wage spiral." 9 Equation (12)

corresponds to such a phenomenon: the changes in relative wages

("leapfrogging") determine the rate of inflation. The rate of this

"wage-wage spiral" is seen below as determined by the level of

the parameter a and the structure of the economy: this consists

of the demand curves of the firms, the bargainings between the

unions and the firms, and the behavior of the firms in setting prices.

It is worth noting that the assumptions necessary to arrive

at (12) were symmetry, nonsynchronization and invertibility.

Therefore the particular monopoly and union-bargaining behavior

assumed - as important as they may be for particular solutions -

are not, by themselves, the keys to the inflationary processes de-

scribed.

Finally returning, as in the last section, to the specific ex-

ample, and collecting equations:

MR= MC yields:

(13) P1i t='/2(ap2, t+Wli 0) for all t

(14) P2, t=1/2(apl, t+w2, t) for all t.

The condition that unions maximize income yields:

(15) W1,2t=a2- for all t

12, 2t 1 +ye

8. J. M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and

Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1936), p. 14. "In other words the strug-

gle about money wages primarily affects the distribution of the aggregate

real wage among labor groups and not its average amount per unit of employ-

ment, which depends, as we shall see, on a different set of forces. The effect

of combination on the part of a group of workers is to protect their relative

wage. The general level of real wages depends on the real forces of the eco-

nomic system."

9. See, in particular, W. Fellner, et al., The Problem of Rising Prices

(Paris: Organizationfor European Economic Cooperation, 1961), pp. 53-54.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

368 QUARTERLYJOURNALOF ECONOMICS

(16) W2,2t+1 =a 1' for all t.

P1,2t+1 1+ye

The condition that bargaining occurs in January for union one gives

us:

(17) Wi,2t=Wl,2t+1 for all t

and that bargaining occurs in July for union two gives us:

(18) W2, 2t+1 =W2, 2t+2 for all t.

Using (13), (14), (17) and (18) equations (15), (16), (17) and

(18) can be rewritten as:

(15') Ply2t = az where Z= 2( y

P2, 2tZ=(y)

(16') P2, 2t+1 az

P1, 2t+1

(17') 2pi, 2t-aP2,2t=2p1y 2t+1-aP2, 2t+1

(18') 2P2, 2t+1-api, 2t+l=2p2, 2t+2-api, 2t+2.

Solving (15'), (16'), (17') and (18') we find that

(19) Pl, 2t+1 = (2_a2z)zP1i 2t

a2z (2z - 1)

(20) Pl, 2t+2= - 2-a2z P, 2t+1

and, most importantly,

ra

P121t+ 2-)1

(2) Ply,2t 2-a z

It is also possible to check that the relative wage W1,2t/W2, 2t is also

equal to a (2z-1) / (2-a2z).

Equation (21) gives the short-run Phillips Curve. This short-

run Phillips Curve has the expected properties that:

(l2t+2)

P

Pl, 2t

>

Da >0o

and

aPl, 2t+2

Pi, 2t

>0

Dye

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 369

as long as 2- a2z>0. This, however, is the relevant range in our

model, since otherwise equation (20) would denote inconsistent

(negative) price behavior.

But the next question which arises is the nature (or the exis-

tence) of a long-run Phillips Curve. In long-run equilibrium, as

before, price expectations should be realized. Remembering the

definition of ye the expected multiple of increase of P2 between

2t and 2t+1 - and applying symmetry, it is possible (using (20))

to write yA (the actual multiple of inflation of P2 between 2t and

2t+1 as a function of the expected inflation ye and a.

(22) A a2z (2z-1) a2ye (1+2ye)

'Y 2-a2z 2(1+ye)2_a2(1+2ye) (+l1ye)

and in equilibrium

(23) yA = ye

Equation (22) is remarkably similar to our old friend (7). First, for

a = 4/3, ye =1 is a double root. This should occasion no surprise -

considering the remarks of the last section. Second, for a > 4/3,

yA (ye) has the same shape as the function in Figure I. Upper roots

are, therefore, stable; lower roots are therefore unstable. Exactly

the same analysis with exactly the same qualifications which ap-

plied to the system in the last section can be repeated here. Begin-

ning with nondeflationary static expectations with a>4/3 the sys-

tem will gravitate to a rate of inflation determined by a. This rate

of inflation is locally stable and it increases with higher values of

a. In this restricted and qualified sense there is a long-run Phil-

lips Curve.

Money enters just as money entered before. Suppose that ag-

gregate demand is the sum of consumption demand, investment de-

mand, and government demand (assuming that the economy is

closed). There will be a relation between a and monetary policy.

Static macroeconomic theory shows that this sum will depend on

(a) the level of government expenditures, (b) the level and rates

of real taxation, and (c) the level of real balances. Suppose that

(a) and (b) are fixed; and suppose that the nominal level of the

money supply is increasing at a given rate A. In Figure II if the

rate of employment is larger than P(A), real balances and hence

aggregate demand are decreasing. Similarly if the rate of employ-

ment is less than P (X), real balances (and hence aggregate demand)

are increasing. P(X) represents the equilibrium rate of employment

for the rate of increase of the money supply X- with given policies

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

370 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

(dp/dt)/ p Phillips Curve

P(A) Employment

FIGUREII

in real terms for the level of government taxation and expenditure.

But there is one additional warning due: while a rise in real

balances can raise demand to any given level, even with negligible

real balances, demand may exceed supply. This is one clear element

in Bresciani-Turroni's account of the 1923 German hyperinflation:

the reduction in demand from the reduction in real balances was not

sufficient to allow the government to finance its operations from the

expansion of the money supply.' The sum of private plus public

real demands exceeded the full employment potential of the econ-

omy.

In the traditional Keynesian model of inflation 2 and also in

Friedman's Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money 3 a further com-

plication is added: the aggregate demand relations depend on the

rate of price inflation. In the Keynesian view the level of consump-

tion, investment and possibly also government demand depends on

the rate of inflation: because the spending today depends on bud-

gets made yesterday. This should not affect the earlier analysis:

suppose that the money supply is increasing at the rate A. In the

long run if prices are rising at a rate less than A, real balances are

rising (which shifts the consumption function outward), or if prices

are rising at less than A, real balances are falling. Eventually as

long as the many functions of the economy are stable (the consump-

tion function, investment function, tax function (in real terms) and

government expenditure), equilibrium is approached. Friedman,

1. Bresciani-Turroni,op. cit. Cagan shows the regularity with which real

balances decline in hyperinflation. P. Cagan, "The Monetary Dynamics of

Hyperinflation," in M. Friedman (ed.), Studies in the Quantity Theory of

Money (University of Chicago Press, 1956).

2. J. M. Keynes, How to Pay for the War (New York: Harcourt, Brace,

1940).

3. Chicago University Press, 1956.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 371

on the other hand, emphasizes the shift of the demand for money

due to the rate of inflation. The relevant rate of interest for the

holder of money is the nominal rate of interest: the real rate of

interest plus the rate of inflation. Again, however, the same logic

holds: if the price level increases at a slower rate than the money

supply, real balances rise (and hence aggregate demand), and sim-

ilarly if the price level rises at a faster rate than the money supply,

real balances (and hence aggregate demand) decline. The result

will be the equilibrium previously described - but again the same

caveat applies: an overambitious program of expenditure (public

plus private) will result in hyperinflation -for the aggregate de-

mand curve and the aggregate supply curve may never meet

even at zero real balances.

IV

The theory of the last sections would appear all very special

were it not possible to motivate the results in far greater generality.

This generalization is provided by Bent Hansen's Chapter IX

of A Study in the Theory of Inflation.4

Following Hansen a system is considered which has n goods

or factors of production. As in A Theory of Inflation it is a condition

of economic rationality that the demand curves and supply curves

of each of these goods or factors be homogeneous of degree zero for

a given level of real balances. Therefore we write

(24) Di=Di(pi, . . ., pn;;M/pi) i-=, . . ., n

(25) Si= Si(pi, . .,pn; M/lp) i = 1 . . . , n

and in static equilibrium

(26) Di = Si.

Each of the n Si and Di equations can be considered as equa-

tions in relative prices and real balances. Therefore without loss of

generality (24), (25) and (26) can be written

(28) D=sD(,1?,,'j~P2 )nM

(28) Si =Si (1, P * p P

and, in equilibrium

(29) Di = S

4. London: Allen and Unwin, 1951.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

372 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

And, if nothing unusual occurs, it can be seen (in the so-called

normal case) equations (27), (28) and (29) can be solved for the

unknowns

D ,i=l, . , n

Sii=1, . . ., n

and pi/pi, i= 2, . . . , n and M/pl.

This, of course, is the reasoning behind Patinkin's famous volume

- and monetary neutrality holds.

But in Sections II and III there is a system of lagged adjust-

ment to price changes. This can be approximated, following Hansen

(in turn following Samuelson), by saying that (dpi/dt) /p, =

Fi(Di-Si). The rate of change of the ith price depends on the dif-

ference between the demand and the supply of the ith commodity.

Fj has the property that Fi(O) =0, F'i>O: price changes are zero

if demand equals supply; and the greater the excess demand the

greater the rate of price increase.

In this case, for long-run equilibrium, the rate of change of

the price level is equal to the rate of change of the money supply

(which was previously called A). Therefore in the long run it is

not true that Di=Si, which would imply that (dpi/dt)/pi would be

zero. Rather, in the long run

(30) Di= Di (1 P2/Pl) . . . X Pn/Pl;MIPI) A)

(31) Si=Si (1; P-2/Pi; . .. X Pn/Pl;MIPli A)

and

(32) F. (Di,-S.) =A

It may be possible to solve these equations for the 3n unknowns

Pi/Pi i=2, . .. , n, M/pl

Dj, i=l,..., n

and

Se, i = 1 . . . ,n.

And in general the real solution to the system will depend on the

value of A (which is the rate of increase of the money supply).5

5. Another way to look at this problem is that we have a system of

balanced growth equations as in P. A. Samuelson and R. M. Solow, "Balanced

Growth Under Constant Returns to Scale," Econometrica, Vol. 21 (July 1953).

Both M. Morishima and F. M. Fisher have suggested that such systems could

be used to talk about inflation. See M. Morishima, "Proof of a Turnpike

Theorem: The 'No Joint Production Case,"' Review of Economic Studies,

XXVIII (Feb. 1961); and A. Ando, F. M. Fisher, and H. A. Simon, Essays

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RELATIVE WAGES AND THE RATE OF INFLATION 373

The "Keynesian" theory of wage adjustment of Section III

gives a precise rationale for an adjustment mechanism of the Han-

sen-Samuelson variety; in turn it leads to the nonneutrality of

money -and therefore a Phillips Curve. Reinterpreting the as-

sumptions of Sections II and III, nonsynchronization gives form to

the various Fi's -and the presence of noncompetitive markets

keeps the Fe's from degeneracy: with the markets assumed, the

greater the degree of competition the greater is the slope of the Fj

functions; in the limit money is again neutral.

V

Our model differs considerably from most of the standard

models of inflation: it has been shown that there are considerable

differences from the usual quantity-theory-of-money approach to

inflation: in the long run, the rate of increase of the money supply

determines the degree of full employment.

On the other hand, in the usual demand-pull theories of in-

flation price rises have a purpose: "to cheat the slow to spend of

their desired shares" of total income.6 This is the heart of Keynes 7

and Smithies.8 But in our model inflation occurs without any tele-

ological purpose of destroying aggregate demand - although, as

seen in Section III, this can be easily incorporated into the model.

And yet this is not a simple model of cost-push either, for the

wage rises would not occur without the price rises just as the price

rises would not occur without the wage rises. Rather this is a

model of spontaneous inflation in which the chicken and the egg of

wage and price rises are mutually the causes of each other. Han-

sen's Walrasian model of inflation is most similar.9

The heart of our system is the gaps between the supply and

demand equilibria, whose continued incompatibility is allowed by

the nature of the adjustment process. Examples have been given

before of systems where the system of adjustment allows a toler-

ance for continued disequilibrium, with resulting rising prices and

wages. The notion of "leapfrogging" has already been mentioned.'

J. C. R. Dow has suggested a situation in which unions and firms are

on the Structure of Social Science Models (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press,

1963).

6. P. A. Samuelson and R. M. Solow, "Analytical Aspects of Anti-Infla-

tion Policy," American Economic Review, L (May 1960).

7. Keynes, How to Pay for the War, op. cit.

8. A. Smithies, "The Behavior of Money National Income," this Journal,

LVII (Nov. 1942).

9. Hansen, op. cit.

1. Fellner, et al., op. cit.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

374 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS

each biddingfor sharesof output,whose sum exceedsUnity.2Turvey

has suggested a similar process.3 The additional element of the

spontaneous inflation here, whatever kind of spiral it may be, is

its explicit dependence upon demand and expectations.

Finally this paper has left us with many exercises unfinished

and several questions to be answered. First of all, many different

industrial structures could be substituted for the example of monop-

olistic competition and applied to this framework. Similarly vari-

ous different bargaining solutions between unions and employers

can be substituted. One possible variant on this theme is an econ-

omy with a monopolistic and a competitive sector - where the

monopolistic sector represents "industry" and the competitive sec-

tor represents "agriculture." Such a model could be used to describe

inflationary processes in underdeveloped economies.

But more important is the introduction of many grades of labor.

For it is important to know the mechanism whereby labor-training

programs, etc., shift the Phillips Curve and thereby make more

employment possible. In addition it is necessary to have such a

macroeconomic view in order to compare the costs and the benefits

of such training programs. Similarly it is important to have models

with several types of employers to evaluate the effects of such pro-

grams as additional government employment of low-skilled workers.

Further, the high councils of the United States government

appear to believe some Phillips-Curve theory.4 But as Professor

Kuh has urged,5 in a model with heterogeneous labor (and seg-

mented markets) the competition between the "top" and the "bot-

tom" of the labor force may be weak. The implication is that

unemploymentmay, in past cycles, be correlatedwith the bargain-

ing power of wage earnersbut at the same time it may be structur-

ally independent. If this is the true view of the economy, the

Phillips Curve can perhapsbe structurallyaltered; a structurefor

inflation theory is necessary to decide whether this is in fact the

case.

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

2. J. C. R. Dow, Oxford Economic Papers, N.S. Vol. 8 (Oct. 1956).

3. R. Turvey, "Some Aspects of the Theory of Inflation in a Closed

Economy," Economic Journal, LXI (Sept. 1956).

4. In particular, see Economic Report of the President, 1962, p. 44, for

an especially clear and authoritative statement of the believed relation be-

tween unemployment and inflation.

5. See Kuh, op. cit.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.79 on Tue, 17 Jun 2014 05:48:20 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- AlasdaircLeod GibsonsParadoxDocument17 pagesAlasdaircLeod GibsonsParadoxron9123No ratings yet

- Nobel Prize LecturesDocument23 pagesNobel Prize Lecturessmarty_abhi12@yahoo.co.in100% (2)

- Fischer 1977Document15 pagesFischer 1977pilymayor2223No ratings yet

- Ball, L., y Mankiw, G. (1995) - Relative-Price Changes As Aggregate Supply Shocks. The Quaterly Journal of Economics, 110 (1), 161-193.Document34 pagesBall, L., y Mankiw, G. (1995) - Relative-Price Changes As Aggregate Supply Shocks. The Quaterly Journal of Economics, 110 (1), 161-193.skywardsword43No ratings yet

- Olivera PassiveMoney 1970Document11 pagesOlivera PassiveMoney 1970Héctor Juan RubiniNo ratings yet

- Kaldor 1975Document12 pagesKaldor 1975zatrathustra56No ratings yet

- Principle 10 - FINALDocument6 pagesPrinciple 10 - FINALJapaninaNo ratings yet

- Money, Output and Inflation in Classical Economics : Roy. GreenDocument27 pagesMoney, Output and Inflation in Classical Economics : Roy. GreenBruno DuarteNo ratings yet

- Stolper Samuelson 1941Document17 pagesStolper Samuelson 1941Matías OrtizNo ratings yet

- Fact and Fancy in International Economic Relations: An Essay on International Monetary ReformFrom EverandFact and Fancy in International Economic Relations: An Essay on International Monetary ReformNo ratings yet

- Samuelson - Solow - Phillips Curve PDFDocument19 pagesSamuelson - Solow - Phillips Curve PDFGuilherme CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Milton Friedman - Studies in The Quantity Theory of Money-University of Chicago Press (1956)Document274 pagesMilton Friedman - Studies in The Quantity Theory of Money-University of Chicago Press (1956)Ashu KhatriNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:15:53 +00:00Document83 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:15:53 +00:00skywardsword43No ratings yet

- The Monetarist-Keynesian Debate and The Phillips Curve: Lessons From The Great in AtionDocument34 pagesThe Monetarist-Keynesian Debate and The Phillips Curve: Lessons From The Great in AtionHiromiIijimaCruzNo ratings yet

- Natural Unemployment, The Role of Monetary Policy and Wage Bargaining: A Theoretical Perspective Abstract (WPS 133) Stefan Collignon.Document22 pagesNatural Unemployment, The Role of Monetary Policy and Wage Bargaining: A Theoretical Perspective Abstract (WPS 133) Stefan Collignon.Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard UniversityNo ratings yet

- Olivera StructuralInflationLatinAmerican 1964Document13 pagesOlivera StructuralInflationLatinAmerican 1964Héctor Juan RubiniNo ratings yet

- A Century of Nominal History in Argentina: Monetary Instability and Non-NeutralitiesDocument39 pagesA Century of Nominal History in Argentina: Monetary Instability and Non-NeutralitiesignacioNo ratings yet

- Sharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)Document19 pagesSharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)julioacev0781No ratings yet

- Rabin A Monetary Theory 76 80Document5 pagesRabin A Monetary Theory 76 80Anonymous T2LhplUNo ratings yet

- The Short LongDocument19 pagesThe Short Longcreditplumber100% (1)

- Financial CrisisDocument9 pagesFinancial CrisisRachel DuhaylungsodNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument5 pagesJurnal InternasionalRamdhan AlghozaliNo ratings yet

- Eichner - 1973 - A Theory of The Determination of The Mark-Up UnderDocument18 pagesEichner - 1973 - A Theory of The Determination of The Mark-Up Underçilem günerNo ratings yet

- Friedman's Theory of the Consumption FunctionDocument7 pagesFriedman's Theory of the Consumption FunctionMaster 003No ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Review of LiteratureDocument49 pagesChapter 2: Review of LiteratureRehan UllahNo ratings yet

- The Short Long: Speech by Andrew G Haldane, Executive Director, Financial Stability, and Richard DaviesDocument19 pagesThe Short Long: Speech by Andrew G Haldane, Executive Director, Financial Stability, and Richard DavieswasunorthNo ratings yet

- 9-Risk Perception Psychology PDFDocument9 pages9-Risk Perception Psychology PDFSobi AfzNo ratings yet

- Microeconomic Theory Old and New: A Student's GuideFrom EverandMicroeconomic Theory Old and New: A Student's GuideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Competitie PerfectaDocument18 pagesCompetitie PerfectaAndrea AndreeaNo ratings yet

- The Case For Fixed: Exchange Rates, 1969Document27 pagesThe Case For Fixed: Exchange Rates, 1969Sebastian PaglinoNo ratings yet

- Inefficient Markets and The New FinanceDocument18 pagesInefficient Markets and The New FinanceMariam TayyaNo ratings yet

- Complexity Innovation and The Regulation of Modern Financial MarketsDocument68 pagesComplexity Innovation and The Regulation of Modern Financial MarketsGeorge BilkisNo ratings yet

- Plenty of Nothing: The Downsizing of the American Dream and the Case for Structural KeynesianismFrom EverandPlenty of Nothing: The Downsizing of the American Dream and the Case for Structural KeynesianismNo ratings yet

- AnalysisDocument38 pagesAnalysispasler9929No ratings yet

- Multiple Interest Rates and ABCTDocument46 pagesMultiple Interest Rates and ABCTIoproprioioNo ratings yet

- Fed Inflation RuddDocument27 pagesFed Inflation RuddAskar MulkubayevNo ratings yet

- Lessons From The 1930sDocument19 pagesLessons From The 1930sGeorge_G92No ratings yet

- Diamond 1984Document21 pagesDiamond 1984Cristian Fernando Sanabria BautistaNo ratings yet

- Economic Schools of ThoughtDocument6 pagesEconomic Schools of ThoughtSimon LonghurstNo ratings yet

- Inflation and the Output-Inflation Trade-OffDocument90 pagesInflation and the Output-Inflation Trade-OffCristiano RodrigoNo ratings yet

- EMH To Behavioral Finance - ShillerDocument44 pagesEMH To Behavioral Finance - ShillerrexyfloydNo ratings yet

- The Inflation-Unemployment Tradeoff: The Neutrality of Money The Keynesian RevolutionDocument7 pagesThe Inflation-Unemployment Tradeoff: The Neutrality of Money The Keynesian RevolutionShrimanta SatpatiNo ratings yet

- MIll and Wage FundDocument25 pagesMIll and Wage FundJavy De la MorenaNo ratings yet

- Stolper ProtectionRealWages 1941Document17 pagesStolper ProtectionRealWages 1941keeshiaNo ratings yet

- (IMF Staff Papers) The Impact of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Under Flexible Exchange Rates and Alternative Expectations StructuresDocument34 pages(IMF Staff Papers) The Impact of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Under Flexible Exchange Rates and Alternative Expectations StructuresNida KaradenizNo ratings yet

- Inflation: Mechanics Welfare: Its and CostsDocument51 pagesInflation: Mechanics Welfare: Its and CostsMiguel AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- The Non Sequitur in the Revival of Monopsony TheoryDocument10 pagesThe Non Sequitur in the Revival of Monopsony TheoryCrystal HarrisNo ratings yet

- Friedman M Essays in Positive EconomicsDocument336 pagesFriedman M Essays in Positive Economicsluchi lovoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Inflation On Farmers and AgricultureDocument43 pagesThe Impact of Inflation On Farmers and AgricultureSharif BalouchNo ratings yet

- The Long Swings in Economic Understanding: Axel LeijonhufvudDocument32 pagesThe Long Swings in Economic Understanding: Axel LeijonhufvudArtur CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Oxford University PressDocument40 pagesOxford University Presszatrathustra56No ratings yet

- Keynesian Vs Classical Models and PoliciesDocument8 pagesKeynesian Vs Classical Models and PoliciesSibhat TilahunNo ratings yet

- Conclusion: Interest Rate M' MDocument5 pagesConclusion: Interest Rate M' MAnonymous T2LhplUNo ratings yet

- The Realism of Assumptions Does Matter: Why Keynes-Minsky Theory Must Replace Efficient Market Theory As The Guide To Financial Regulation PolicyDocument30 pagesThe Realism of Assumptions Does Matter: Why Keynes-Minsky Theory Must Replace Efficient Market Theory As The Guide To Financial Regulation PolicymrwonkishNo ratings yet

- 11 Types of Economic Theories ExplainedDocument6 pages11 Types of Economic Theories Explaineddinesh kumarNo ratings yet

- What Explains The Industrial Revolution in East Asia? Evidence From The Factor MarketsDocument25 pagesWhat Explains The Industrial Revolution in East Asia? Evidence From The Factor Marketsbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- eeepinit2Document16 pageseeepinit2biblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- C Effects QF Pernianent and Temporary Tax Policies: A Q Model of InvestmentDocument21 pagesC Effects QF Pernianent and Temporary Tax Policies: A Q Model of Investmentbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Assessing TheDocument23 pagesA Framework For Assessing Thebiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- AlibertiDocument29 pagesAlibertibiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Wind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andDocument6 pagesWind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Implementing An International CarbonDocument17 pagesImplementing An International Carbonbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- What Explains The Industrial Revolution in East Asia? Evidence From The Factor MarketsDocument25 pagesWhat Explains The Industrial Revolution in East Asia? Evidence From The Factor Marketsbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- The Rebound Effect and TheDocument8 pagesThe Rebound Effect and Thebiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Wind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andDocument6 pagesWind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Cap and Trade A Sufficient or NecessaryDocument28 pagesCap and Trade A Sufficient or Necessarybiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Policy Instruments For Renewable EnergyDocument4 pagesPolicy Instruments For Renewable Energybiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Assessing TheDocument23 pagesA Framework For Assessing Thebiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- BalancingDocument3 pagesBalancingbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Implementing An International CarbonDocument17 pagesImplementing An International Carbonbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Wind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andDocument6 pagesWind Power in Argentina Policy Instruments andbiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- Policy Instruments For Renewable EnergyDocument4 pagesPolicy Instruments For Renewable Energybiblioteca economicaNo ratings yet

- 134 - Realubit V JasoDocument2 pages134 - Realubit V JasoJai HoNo ratings yet

- Kind engineer seeks understanding partnerDocument17 pagesKind engineer seeks understanding partnerBrother PeterNo ratings yet

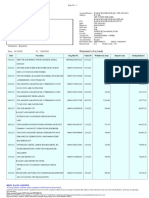

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument7 pagesStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceAdithi KNo ratings yet

- The ICT Asian KillzoneDocument3 pagesThe ICT Asian Killzoneazhar500No ratings yet

- BCOM (Hons) - 2023-Sem - II-IV-VI (CBCS) - LOCF-10-04-2023Document2 pagesBCOM (Hons) - 2023-Sem - II-IV-VI (CBCS) - LOCF-10-04-2023tanisha chauhanNo ratings yet

- Iifl PMSDocument12 pagesIifl PMSkaviraj sasteNo ratings yet

- Implementasi Insentif Pajak Menurut Model G Edward IiiDocument13 pagesImplementasi Insentif Pajak Menurut Model G Edward Iii03Ni Putu Widya AntariNo ratings yet

- Assignment3 S12022 (ECON1020) StudentTemplate Ccf40f6b b198 4e8ggd 8af1 C152ae540f51Document7 pagesAssignment3 S12022 (ECON1020) StudentTemplate Ccf40f6b b198 4e8ggd 8af1 C152ae540f51microbiology biotechnologyNo ratings yet

- NYC Spent $9M Sending Out $5 Bills With Mental Health SurveyDocument1 pageNYC Spent $9M Sending Out $5 Bills With Mental Health SurveyRamonita GarciaNo ratings yet

- NUMERICAL QUESTIONS ON INDIFFERENCE CURVES AND BUDGET LINESDocument2 pagesNUMERICAL QUESTIONS ON INDIFFERENCE CURVES AND BUDGET LINESIsmith PokhrelNo ratings yet

- TSP of 2019-2020 Group 1Document13 pagesTSP of 2019-2020 Group 1tatenda rupangaNo ratings yet

- Hombres y BestiasDocument223 pagesHombres y BestiasPaul GuillenNo ratings yet

- Camarilla EquationDocument4 pagesCamarilla Equationmarcosfa81No ratings yet

- Granny Flores de PrimaveraDocument10 pagesGranny Flores de PrimaveraYessica Chamorro100% (1)

- Pipe ReinforcementDocument12 pagesPipe ReinforcementZohaibNo ratings yet

- Module 1 / Units 1-2 / Test 1: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 5 4 8 3 7 2 1 9 Two Five Three One Seven Eight Nine FourDocument2 pagesModule 1 / Units 1-2 / Test 1: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 5 4 8 3 7 2 1 9 Two Five Three One Seven Eight Nine FourAnita Szabó80% (5)

- Property Renovation LondonDocument9 pagesProperty Renovation LondonbiparotNo ratings yet

- Module 5 in Abm Applied EconomicsDocument16 pagesModule 5 in Abm Applied EconomicsKimberly JoyceNo ratings yet

- Market Volatility BulletinDocument22 pagesMarket Volatility BulletinThomasNo ratings yet

- PRDP Module 1 Infrastructure Subprojects Procurement GuidelinesDocument140 pagesPRDP Module 1 Infrastructure Subprojects Procurement GuidelineskenvysNo ratings yet

- Life at Adventz Oct 2017 by TS DarbariDocument32 pagesLife at Adventz Oct 2017 by TS DarbariT S DarbariNo ratings yet

- Pranav Sir - Maths Formula Book - Dec 2022 PDFDocument6 pagesPranav Sir - Maths Formula Book - Dec 2022 PDFSiddhi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To OPDocument35 pagesIntroduction To OPCharisa SamsonNo ratings yet

- Layered Process Audit Checklist (LPA)Document5 pagesLayered Process Audit Checklist (LPA)ALBERTO ALVARADO CARRILLONo ratings yet

- Global Enabling Trade Report 2008Document436 pagesGlobal Enabling Trade Report 2008World Economic Forum100% (36)

- Lucid Colloids LTD (Meglasiya) : Moam. LBTBDocument26 pagesLucid Colloids LTD (Meglasiya) : Moam. LBTBHussein Abdou HassanNo ratings yet

- Prepare Second Edition Level 6: Unit 9 Grammar: PlusDocument2 pagesPrepare Second Edition Level 6: Unit 9 Grammar: PlusHubert PawlikNo ratings yet

- Xii Economics Excellence Series, Ziet BBSRDocument296 pagesXii Economics Excellence Series, Ziet BBSRnagartanishq2No ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR UGANDA ECONOMY AssignmentDocument14 pagesINTERNATIONAL TRADE AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR UGANDA ECONOMY Assignmentwandera samuel njoyaNo ratings yet

- Product Mix AssignmentDocument8 pagesProduct Mix AssignmentAjoy Thakuria67% (3)