Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sellitto 2021

Uploaded by

JudybenavidesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sellitto 2021

Uploaded by

JudybenavidesCopyright:

Available Formats

Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes

Research

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ierp20

Outcome measures for physical fatigue in

individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic

review

Giovanni Sellitto, Alessia Morelli, Susanna Bassano, Antonella Conte, Viola

Baione, Giovanni Galeoto & Anna Berardi

To cite this article: Giovanni Sellitto, Alessia Morelli, Susanna Bassano, Antonella Conte, Viola

Baione, Giovanni Galeoto & Anna Berardi (2021): Outcome measures for physical fatigue in

individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review, Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics &

Outcomes Research, DOI: 10.1080/14737167.2021.1883430

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2021.1883430

Accepted author version posted online: 28

Jan 2021.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 53

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ierp20

Publisher: Taylor & Francis & Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Journal: Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research

DOI: 10.1080/14737167.2021.1883430

Outcome measures for physical fatigue in individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic

review

T

IP

Giovanni Sellitto1, Alessia Morelli1 , Susanna Bassano1, Antonella Conte2,3, Viola Baione2,

R

Giovanni Galeoto2 , Anna Berardi2

SC

1. Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy

U

2. Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5,

AN

00185, Rome, Italy

3. IRCCS Neuromed Pozzili, Italy

M

D

TE

*Corresponding author:

EP

Galeoto Giovanni

C

Viale dell’Università 30, Rome

AC

Email: giovanni.galeoto@uniroma1.it

Outcome measures for physical fatigue in individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic

review

Information Classification: General

Giovanni Sellitto1, Alessia Morelli1 , Susanna Bassano1, Antonella Conte2,3, Viola Baione2,

Giovanni Galeoto2 , Anna Berardi2

4. Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy

5. Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5,

00185, Rome, Italy

T

6. IRCCS Neuromed Pozzili, Italy

IP

R

SC

*Corresponding author:

U

AN

Galeoto Giovanni

Department of Human Neurosciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185,

M

Rome, Italy

D

Email: giovanni.galeoto@uniroma1.it

TE

EP

C

AC

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Physical fatigue can be a common reason for early retirement or sick leave since it

appears in the earliest stages of multiple sclerosis (MS). Therefore, a prompt and accurate diagnosis

is essential. This systematic review aims to identify and describe the instruments used to assess

Information Classification: General

physical fatigue in MS patients with consideration for the languages used to validate the instruments

and their methodological qualities.

Area covered: This study has been carried out through “Medline,” “Scopus,” “Cinhal,” and “Web

of Science” databases for all the papers published before January 24, 2020. Three independent

authors have chosen the eligible studies based upon pre-set criteria of inclusion. Data collection,

T

data items, and assessment of the risk of bias: the data extraction approach was chosen based on the

IP

Cochrane Methods. For data collection, the authors followed the recommendations from the

R

COSMIN initiative. Study quality and risk of bias were assessed using the COSMIN Check List.

SC

Expert opinion: 119 publications have been reviewed. The 45 assessment scales can be divided

into specific scales for physical fatigue and specific scales for MS. The most popular tools are the

U

Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale.

AN

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis; Outcome measures; Physical fatigue; Psychometric properties,

M

Rehabilitation; Reliability; Systematic review; Tools; Validation.

D

TE

EP

C

AC

1. INTRODUCTION

Fatigue occurs in 75-90% of people with Multiple Sclerosis (MS), with 50-60% diagnosed

reporting it as the most common symptom of the disease. Stumbling, tripping, an inability to grasp,

Information Classification: General

and dysarthria are the most significant consequences of fatigue [1] that badly impacts the social and

working lives of people with MS[2]. Moreover, fatigue is a common reason for early retirement[3].

Although physical fatigue is one of the common symptoms of MS, it is still tough to identify it as

related specific to the disease. “Fatigue trait” was defined by the MS Council for Clinical Practice

Guidelines as a “subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual

T

or caregiver to interfere with usual and desired activities”[4]. Until now, the greatest efforts in the

IP

rehabilitation field, the peak of which was the Cochare overview of 2019[5], focused on how to

R

treat fatigue more efficiently without paying enough attention to assess the symptom itself.

SC

Nowadays, a wide range of instruments for assessing physical fatigue exist, namely the Fatigue

Severity Scale (FSS) [6], which is a specific scale to assess physical fatigue interference in any

U

patient’s daily life; also, the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS)[7], which is a scale developed

AN

by the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guideline in 1998.

M

Knowing the scientific instruments to identify the right treatment for assessing physical fatigue is

essential to diagnosing symptoms more efficiently. Our review aims at searching and describing the

D

most common tools used to assess physical fatigue together with all its forms in people with MS.

TE

Secondly, it evaluates the languages used to validate the tools and the methodological quality of the

EP

studies. Therefore, this paper’s primary goal is to identify tools to address physical fatigue both at a

clinical and research level to build a standardized and shared assessment path to go along.

C

2. BODY

AC

A group of researchers from the University of Rome “La Sapienza” rehabilitation professionals and

the Association “Rehabilitation and Outcome measure Assessment” R.O.M.A. has carried out this

study along with several systematic reviews, and together they have validated a lot of outcome

measures in Italy over the past several years. [8], [9], [9]–[16]

Information Classification: General

2.1 Protocol and registration

The protocol has been registered in the International Register of the systematic reviews[17],

PROSPERO website, at the following link

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=176333.

The review has been carried out in compliance with the PRSMA STATEMENT 27-ITEM

T

guidelines for systematic review reporting[15][16].

IP

R

2.2 Inclusion criteria in the review: types of studies and types of participants

SC

The systematic review was confined to the studies focusing on the psychometric qualities of

outcome measures used to assess physical fatigue in people with MS.

U

The studies analyzed in the review include those focusing on the psychometric properties of

AN

physical fatigue specific scales—all the studies validating the outcome measures to assess the ADL

M

and the quality of life. The measures had one or more items assessing physical fatigue as well. The

review has taken into account questionnaires, tests, and both scale validation studies with an

D

operator’s interview and a patient’s self-report. Studies assessing the treatment efficacy but omitting

TE

assessment instrument psychometric properties were excluded. No restriction was placed upon age

EP

or other characteristics of people with MS. Neither time nor location limits were applied to the

bibliographical research.

C

2.3 Inclusion criteria

AC

• Studies of validation and cross-cultural adaptation

• Studies focusing on physical fatigue

• Studies about tests, questionnaires, self-evaluation, and performance-based outcome

measures

• Studies about a group of people with MS

2.4 Exclusion criteria

Information Classification: General

• Trials or studies evaluating the effectiveness of a treatment where the evaluation tool is used

only to make the objective concrete.

• Studies evaluating cognitive fatigue.

• Studies focusing on several neurological diseases without considering people with MS in

detail.

2.5 Research methods aiming at identifying the studies

Studies were identified for inclusion through individualized systematic searches of four electronic

T

IP

databases. All potential studies were identified by three reviewers.

R

2.6 Electronic searches

SC

The review’s primary reviewer developed the search strategy, following consultation with an expert

specialized in systematic review of rating scales and using guidance from relevant past reviews[10],

[19]. U

AN

The initial search strategy was constructed for MEDLINE (via PubMed) on 24th January 2020. A

M

combination of terms and keywords was used: ((“multiple sclerosis”) AND “fatigue”)) AND

D

((((((“scale”) OR “test”) OR “questionnaire”) OR “assessment”) OR “measure”) OR “inventory”)

TE

OR “instrument”) AND (((“validation” OR “validity”) OR “validation studies”) and adapted to

other databases. The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Pubmed);

EP

CINHAL (via EBSCO); SCOPUS; and Web Of Science.

C

We have chosen to use the databases mentioned above as they only index journals that follow the

AC

"peer review" process in order to keep the methodological quality of the study high, this is the

reason why we have also chosen not to use literature gray.

2.7 Studies selection

Titles, keywords, and abstracts identified through the databases were screened independently by

two occupational therapists and one physical therapist.

Information Classification: General

During the first screening, the three editors have removed all the double studies. All the articles the

three editors agreed upon have been included as well as in the second screening.

During the second screening, the full-text of the included studies have been analyzed.

When the screening phase came to an end, the editors decided to include research studies not

mentioned in the database, using pre-set criteria, because general outcome measures were used. We

T

also carried out '' reference checking '' and '' citation tracking '' to identify any studies that could be

IP

included in our review. However, eligibility criteria were considered for one or more items.

R

SC

2.8 Data Collection and risk of bias assessment

Data extraction occurs in conformity with the Cochrane method[20]. Three reviewers independently

U

extracted patient demographics and descriptive information, and each study was keyworded for

AN

generic issues such as language, country, focus, population, and so on[21]. All these data have been

obtained through the information provided within the studies reports. The editors have focused for

M

every single scale of assessment the following psychometric characteristics: Cronbach Alpha for the

D

internal consistency and interrelatedness of items; the ICC for the test-retest reliability and stability

TE

after repeated measurements; and, the criterion validity represented by correlations with a gold

standard. Both the content and the methods of the studies have been assessed from a quality point of

EP

view. The quality of the study and the risk of bias has been weighed through the assessment tool for

C

the observational, cohort, and cross studies for the selection of health status Measurement

AC

(COSMIN checklist-13)[22][23].

The ten elements used to evaluate the methodological quality of the studies included in our review:

Internal consistency, defined as the interrelation between elements; Reliability, defined as stability

after repeated measurements; Measurement error, systematic and random error in a patient's score

that is not attributed to actual changes in the product to be measured; Content validity defined as the

degree to which the content of a patient-reported health-related outcome tool (HR-PRO) adequately

Information Classification: General

reflects the construct to be measured; Structural validity, is the degree to which the scores of an HR-

PRO instrument are an adequate reflection of a dimensionality of the construct to be measured;

Hypothesis testing is the degree to which the scores of an HR-PRO tool are consistent with the

hypotheses; Cross-cultural validity is the degree to which the performance of the elements on a

translated; or, culturally adapted HR-PRO is an adequate reflection of the performance of the

elements of the original version of the HR-PRO tool. The validity of the criterion defined as the

T

IP

degree to which the scores of an HR-PRO instrument adequately reflect a "gold standard";

Reactivity defined as the ability of an HR-PRO instrument to detect the change over time in the

R

structure to be measured; Interpretability is the degree to which qualitative meaning can be assigned

SC

to an instrument's quantitative scores or changes in scores[24].

U

AN

3. CONCLUSION

M

3.1 Study selection: description of the studies and results of the search

D

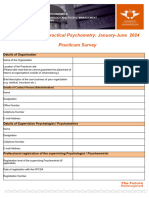

The search strategy identified 10.905 matches. After the removal of duplicates, 5.830 studies were

TE

screened for reading both title and abstract. Subsequently, 162 articles were excluded after reading

the full text. The selection and screening process is highlighted through the flow chart (Figure 1).

EP

3.2 Excluded studies

C

At the first screening of titles and abstracts, studies that did not evaluate the psychometric qualities

AC

or the validated tools did not investigate physical fatigue (e.g., quality of life scales that have no

inherent items) or the sample used did not include MS patients, were not included. Among the

studies that received a full text review, some used the assessment tool for the sole purpose of

measuring the effectiveness of an intervention, others used tools that assessed cognitive fatigue,

while others did not perform a subgroup analysis with MS patients only. Details are reported in

figure 1.

Information Classification: General

In total 5,711 were excluded for ineligibility.

3.3 Included studies

Following compliance with the inclusion criteria, 119 studies[25]–[138] were entered and reviewed,

of which 7[139] evaluated multiple tools simultaneously. Forty-five measurement tools were

identified, and 20 of these were found in multiple studies. A total of 45 tools were found that assess

T

physical fatigue in MS patients[140]. A summary of the descriptive information of the studies is

IP

presented in Table 1.

R

SC

3.4 Study characteristics: types of design and types of participants

All related studies are cross-sectional[26]. The sample size of the studies ranges from 14[103] to

U

9.324[97], [141]. Most participants are under the age of 50, with an average age range of 29,8[49]

AN

to 56,2[32]. The most conspicuous language validations are English and German, respectively, with

32 and 7 validated tools.

M

The most commonly used assessment tools are: the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) created in English

D

(UK)[45] and validated in German (Switzerland)[50], German (Germany)[48], Turkish[47],

TE

Italian[60], English (USA)[52], Arabic, Finnish[55], Russian[44], Greek[56], Swedish [53],

EP

Norwegian[53], Dutch[59] and Persian (Iran)[57]; the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS), created in

English[84] and validated in Turkish[117], Swedish[106], Hungarian[38], Persian[43], Russian[44]

C

and French[128]; the Unidimentional Fatigue Impact Scale (U-FIS) created in English (UK)[51]

AC

and validated in English (USA), English (Canada), Spanish, French, French (Canada), German,

Italian and Swedish[62][73]; the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) validated in English

(UK)[67][61], English (USA)[52], Arabic[75][76], Persian[142], Greek[70], Italian, Spanish,

French, Slovenian[65], German[72], Portuguese (Brazil)[66] and Japanese[71].

3.5 Risk of bias within studies

Information Classification: General

The risk of bias of the studies is not uniform. The methodological quality assessment was carried

out using the COSMIN Checklist-13 tool, shown in Table 4-5. Overall, 76 of 104 studies were

performed with good methodological quality.

Items 1 (in which internal consistency is evaluated), 2 (in which reliability is evaluated), and 4

(construct validity) are the most frequently expected items in the reviewed studies. Conversely,

T

items 7 (cross-cultural validity), 9 (responsiveness), and 10 (interpretability) are those found less

IP

frequently in the studies.

R

Among the articles concerning the FIS, the studies by Armutlu et al., Flensner et al., Mathiowetz et

SC

al., and Lasonczi et al. were judged to be of good quality.

U

As for the MFIS, on the other hand, there are as many as six that possess good methodological

AN

quality: Rooney et al.[61], which also validates the FSS scale, Ghajarzadeh et al.[142], Bakalidou et

al.[70] and Kos et al.[64] Furthermore, the study validating the short-form MFIS-5 by Meca-Llana

M

et al. has an adequate methodological quality.

D

The FSS scale has also been examined in eleven studies and in the works of Otajarvi et al.[55],

TE

Bakalidou et al.[56], Armutlu et al.[47], Ottonello et al.[60], Valko et al.[50] and Rietberg et al.[59]

good methodological quality was found.

EP

3.6 Results of individual outcome measures

C

For each physical fatigue assessment tool, we have collected the validation studies and obtained the

AC

values for Cronbach's alpha and the ICC.

3.7 Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

FSS is a self-administered questionnaire, created in 1989 by LB Krupp[45], which evaluates the

severity of fatigue and its impact on the person's life. It is used in various clinical conditions and

neurological problems, including MS.

Information Classification: General

A literature review shows that the FSS has a good internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha

whose values range from 0.81 to 0.96. ICC values range from 0.43 to 0.89, indicating good scale

reliability.

The psychometric properties of the scale can be found in Table 2-3.

3.8 Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS)

T

IP

The FIS is one of the most common self-assessment scales used for MS to evaluate the impact of

fatigue in three areas of daily life: cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and psychosocial

R

SC

functioning[84]. Therefore, the FIS, on the physical component impacting fatigue, has a good

internal consistency with a Cronbach Alpha whose values range between 0.88 and 0.98. The ICC

U

values vary from 0.78 to 0.95. A single study has an ICC lower than 0.70[95]; these data reveal the

AN

scale’s reliability (Table 2).

3.9 Unidimentional Fatigue Impact Scale (U-FIS)

M

The scale was created in English by Meads in 2009 and derived from the FIS[51]; the goal was to

D

create a one-dimensional scale of 22 elements based on the theory of quality of life-based on needs.

TE

For this instrument, the review highlights a Cronbach's alpha that varies from 0.95 to 0.98, showing

EP

excellent internal consistency, while the ICC varies from 0.86 to 0.92. The data are shown in Table

2.

C

3.10 Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS)

AC

FIS is an abbreviation of MFIS, which as modified consists of a self-made questionnaire that the

patient can answer with or without help. The MFIS has a strong internal consistency with the

Cronbach fluctuating from 0.82 to 0.97. The ICC, on the contrary, goes from 0.75 to 0.95. All the

data can be seen in Table 2.

3.11 Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MS)

Information Classification: General

The NFI-MS is a self-administering questionnaire created by RJ Mills in 2010, in English, and

developed based on interviews addressed to individuals with MS[80]. It is validated in Dutch[78]

and Portuguese[79]. The ICC values indicate good reliability and range from 0.75 to 0.86 (Table 2).

3.12 Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC)

The FSMC is a questionnaire created in 2009 by IK Penner[82] and has been validated in

T

Danish[83] and German[72]. With this tool, it is possible to obtain a total score on physical fatigue

IP

and cognitive fatigue. Cronbach's alpha value is 0.91, while the ICC value is 0.86, thus showing

R

good internal consistency and good reliability, as reported in Table 2.

SC

3.13 Other scales

U

The review highlighted another 38 validated tools divided into two subgroups: specific scales for

AN

physical fatigue (Table 2) and scales for quality of life that present at least one item relating to

physical fatigue (Table 2).

M

Among the latter, the scales with the greatest response in our review are the Multiple Sclerosis

D

Quality of Life (MSQoL) and the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire

TE

(MusiQoL).

EP

3.14 Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life (MSQoL)

C

The MSQOL-54 is a multidimensional health-related quality of life measure that combines both

AC

generic and MS-specific items into a single instrument[114][143]. This 54-item instrument

generates 12 subscales, two summary scores, and two additional single-item measures. The

MSQOL-54 is a structured self-report questionnaire that a patient can generally complete with little

or no assistance. The MSQOL-54 shows good internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha ranging

from 0.75 to 0.96. Test-retest reliability for the 12 subscales is also good, with ICC ranging from

0.66 to 0.96.

Information Classification: General

3.15 Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL)

The Multiple Sclerosis (MS) International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) questionnaire, a multi-

dimensional, self-administered questionnaire, is available in 16 languages[131][138][135], as a

disease-specific quality of life scale that can be applied internationally[131]. The MusiQoL was

validated for the first time in English by M.C. Simeoni in 2008[131]. Characterized by the presence

T

of 31 items for nine dimensions, an average score is calculated for each dimension, which is added

IP

to the other scores. Cronbach's alpha range of values, from 0.34 to 0.96 and those of the ICC from

R

0.59 to 0.99, show a certain variability

SC

3.16 Summary of the quality of the evidence

U

The impact of physical fatigue is significant in all activities, work, and more, for people with MS.

AN

In particular, physical fatigue affects manual dexterity, walking, and language, with a significant

impact from both a social and emotional point of view.[2]

M

In order to investigate physical fatigue in the most precise way possible, while also considering the

D

impact that this will have on the quality of life of people with MS, this review aims to research and

TE

describe the tools for assessing physical fatigue symptoms, while weighing psychometric

properties. Moreover, it aims to identify the cultural adaptations of evaluation tools and evaluate the

EP

studies’ methodological qualities. The data extrapolated from the major databases from January

C

2020 allowed us to identify the most important assessment tools for physical fatigue validated at the

AC

international level. The search was conducted using keywords. No search constraints were placed to

avoid excluding studies of interest for our review and report all the tools and adaptations present in

the literature.

The studies that emerged were published from 1989[6] to 2020[76]. In total, 119 studies track the

use of an evaluation scale.

Information Classification: General

Also, depending on the national contexts, a strong variety of validated tools can be seen. This can

be assumed to have a positive meaning if we consider the clinical context’s multiple needs, but it

certainly leads to the need to make the tools more suitable for several cultural contexts.

These findings suggest that clinicians have contrasting or incomplete information available to use

when making patient care decisions. Furthermore, the lack of consistency and standardization in the

T

evaluation results hindered comparative research and meta-analysis. Further investigation of

IP

outcome measures would benefit patients, researchers, and clinicians. A universal, validated

R

outcome measure is needed to allow comparisons through practice; therefore, researchers

SC

recommended using a standard set of assessments in the future.

The variety of methods used throughout the literature to measure responsiveness illustrates the

U

current problem of defining and standardizing a method or descriptor that can report responsiveness

AN

across various outcome measures accurately.

M

The COSMIN checklist was published in 2010 to assess the methodological quality of the

D

psychometric properties studies[144][145]. The COSMIN framework was developed through an

TE

international consensus process to provide specific recommendations on terminology, taxonomy,

and methodology in studies dealing with PROMs and their measurement properties[22].

EP

This review showed a disparate number of physical fatigue assessment tools, counting as many as

C

45.

AC

Within some of the most used tools, as in the FIS scale and its modified versions, MFIS and U-FIS,

there are also domains investigating social functioning and cognitive functioning, as they arise as

tools for assessing the fatigue symptom in its entirety. However, the presence of a separate domain

for physical functioning allows us to include them in our review and extrapolate psychometric

parameters as tools for assessing physical fatigue.

Information Classification: General

Overall, the review showed us that the scale with the highest number of validations at the

international level is the FSS, with 13 cultural adaptations, which also became extremely reliable.

We described the marked heterogeneity in using evaluation tools and deliberately avoided

suggestions that one evaluation is better than another. Therefore, in the absence of the "perfect"

evaluation tool, we recommend the validation and cultural adaptation of existing evaluation scales

T

in multiple languages to create a common reading index to evaluate physical fatigue in people with

IP

MS.

R

In relation to the review’s secondary objectives, we generally found a good methodological quality,

SC

with about 76 studies on 104, which fell within the COSMIN tool’s parameters.

U

The Italian context has only six culturally validated scales so it must be enriched with new studies,

AN

culturally adaptable to those considered most valid, to be among the tools that emerged from this

review.

M

3.17 Limitation of the study

D

There are obvious limitations in this review that need to be considered. Despite the systematic

TE

search of four electronic databases, it is possible that not all relevant studies have been identified.

EP

The studies may have been published in journals that were not covered by the data. Moreover, the

search string used did not detect studies that validate generic fatigue scales, which, however, having

C

specific items on physical fatigue within them, are eligible for our review.

AC

4 EXPERT OPINION

As of May 2020, the literature data made it possible to identify 45 tools for assessing physical

fatigue in people with MS. It has been acknowledged that the tools with the highest number of

validations at an international level are FSS and MFIS. The FSS has been validated in 13 languages

Information Classification: General

and uses nine items to evaluate physical fatigue, while the MFIS consists of 21 items, but among

these only nine are those investigating physical functioning. Both scales for psychometric values are

valid and reliable. However, the large number of tools identified proves the trend to create new

tools; to reach a “gold standard,” it would be more appropriate to validate and culturally adapt the

tools already available to as many languages as possible. From this point of view, the Italian context

is very sparse. In fact, only six tools have been identified to assess physical fatigue validated in

T

IP

Italian: the FSS, the MFIS, the U-FIS, the FAMS, the MusiQol, and the MSQOL-54.

R

Once we have analyzed the psychometric properties of each scale described in the literature

SC

referring to fatigue in people with MS, physics seems to us, at this point, to clearly define what

should be the context for application of more appropriate scales.

U

Regarding the specific scales for physical fatigue, FSS is the primary. This scale, from a clinical

AN

rehabilitation point of view, investigates the impact of physical fatigue on various aspects of the life

M

for the person with MS, but only in reference to the past 7 days. For possible easy administration

and the rapid data draw, we recommend FSS for subjects with MS relapsing-remitting (MS-RR),

D

perhaps immediately after an acute inflammatory phase, but we do not recommend it for research

TE

purposes.

EP

Another scale that we are interested in including in our recommendations is the FIS with its

variants, U-FIS and MFIS. The FIS was originally designed to evaluate the effects of fatigue on the

C

quality of life in patients with chronic diseases. In particular, we recommend it for use in people

AC

with MS in its secondary progressive (MS-SP) and primary progressive (MS-PP) forms. For

research purposes, we recommend MFIS, which is always able to investigate the three areas of

functioning of a person affected by MS with physical fatigue but does so with 21 targeted items and

therefore is more suited to collect data from a large number of patients.

Information Classification: General

The U-FIS, on the other hand, we recommend for research purposes because it is easy and quick to

administer, whereas in the clinical rehabilitation field, we promote its use in patients with

progressive MS, but with a significant level of EDSS disability[146], as the 22 elements that

compose U-FIS are based on a theory of quality of life is based on needs being met.

Among the scales that primarily investigate the quality of life for people with MS, we recommend

T

the FAMS, the MSQOL-54, and the MusiQoL.

IP

The FAMS is a questionnaire consisting of 59 items that evaluates six main aspects of quality of

R

life. This tool, like the FSS, investigates only the previous 7 days, so here too we recommend, for

SC

clinical rehabilitation its use, in the SM-RR form, but we do not recommend it for research use.

U

The MusiQoL, on the other hand, is a self-administering questionnaire, so before using it in a

AN

clinical rehabilitation setting, it is advisable to carefully evaluate the cognitive level of the person

with MS. It investigates nine dimensions which we consider very complete, but the heterogeneity of

M

the psychometric values that emerged from the review makes us dissent from recommending it

D

either for clinical rehabilitation or research purposes. Conversely, we suggest and promote the use

TE

of MSQOL-54 for research and for clinical rehabilitative use for SM-RR forms, yet even moreso in

chronic MS forms, as the twelve parameters it investigates can be very useful in people with many

EP

years of illness behind him. Table 1

C

Finally, we do not recommend the use of the NFIS-MS or the GNDS scales either in clinical

AC

rehabilitation or in rehabilitation research, as these, albeit with relevant psychometric values, are

purely medical scales.

In conclusion, for MS-SP and MS-PP we recommend the use of FIS, MFIS and U-FIS whereas for

MS-RR we recommend the use of FSS, FAMS, MusiQoL. Our recommendations have been

elaborated on the basis not only of items that can best represent MS, but also of the sample used for

the validation study.

Information Classification: General

We recommend that future studies enrich and integrate the Italian context of rehabilitation,

culturally adapting, among the tools that emerged from this review, those deemed most valid to

create standardized and shareable evaluation paths. In addition, we hope that specific scientific

societies of each branch of rehabilitation will promote the clinical rehabilitation use among their

professionals of these scales and that they invest resources for the validation of as many tools as

possible among those that have proved to be the most reliable.

T

IP

R

SC

Funding

This paper was not funded.

U

AN

Declaration of interest

M

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a

financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants

D

or patents received or pending, or royalties.

TE

EP

Reviewers Disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

C

Availability of data and material

AC

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon

reasonable request.

Figures and Tables

Authors confirm that all figures and tables are original.

Information Classification: General

REFERENCES

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••)

to readers.

T

[1] Occupational therapy and neurological conditions. 2016.

IP

[2] J. D. Fisk, A. Pontefract, P. G. Ritvo, C. J. Archibald, and T. J. Murray, “The Impact of

Fatigue on Patients with Multiple Sclerosis,” Can. J. Neurol. Sci. / J. Can. des Sci. Neurol.,

1994.

R

[3] I. Dyck and L. Jongbloed, “Women with multiple sclerosis and employment issues: A focus

on social and institutional environments,” Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000.

SC

[4] S. R. Schwid, M. Covington, B. M. Segal, and A. D. Goodman, “Fatigue in multiple

sclerosis: Current understanding and future directions,” J. Rehabil. Res. Dev., 2002.

[5] B. Amatya, F. Khan, and M. Galea, “Rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis: An

U

overview of Cochrane Reviews,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019.

**this very recent systematic review reports recommendations about rehabilitation for people

AN

with Multiple Sclerosis, with a focus on fatigue.

[6] L. B. Krupp, “The Fatigue Severity Scale,” Arch. Neurol., 1989.

[7] M. S. C. for C. P. Guidelines, “Fatigue and multiple sclerosis: evidence-based management

strategies for fatigue in multiple sclerosis,” Paralyzed Veterans Am., 1998.

M

[8] G. Galeoto et al., “General Sleep Disturbance Scale: Translation, cultural adaptation, and

psychometric properties of the Italian version,” Cranio - J. Craniomandib. Pract., 2019.

[9] A. Savona et al., “Evaluation of intra- and inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity of the

D

Italian version of the Jebsen–Taylor Hand Function Test in adults with rheumatoid arthritis,”

TE

Hand Ther., 2019.

[10] G. Galeoto et al., “The outcome measures for loss of functionality in the activities of daily

living of adults after stroke: a systematic review,” Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2019.

**This study is a systematic review on outcome measures for loss of functionality in the

EP

activities of daily living of adults after stroke

[11] G. Romagnoli et al., “Occupational Therapy’s efficacy in children with Asperger’s

syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials,” Clin. Ter., 2019.

C

[12] A. Berardi, G. Galeoto, L. Lucibello, F. Panuccio, D. Valente, and M. Tofani, “Athletes with

disability’ satisfaction with sport wheelchairs: an Italian cross sectional study,” Disabil.

AC

Rehabil. Assist. Technol., 2020.

[13] F. Miniera, A. Berardi, F. Panuccio, D. Valente, M. Tofani, and G. Galeoto, “Measuring

Environmental Barriers: Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Italian Version of the

Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors (CHIEF) Scale,” Occup. Ther. Heal.

Care, 2020.

[14] F. Panuccio et al., “General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS-IT) in people with spinal cord

injury: a psychometric study,” Spinal Cord, 2020.

[15] F. Panuccio et al., “Development of the Pregnancy and Motherhood Evaluation

Questionnaire (PMEQ) for evaluating and measuring the impact of physical disability on

pregnancy and the management of motherhood: a pilot study,” Disabil. Rehabil., pp. 1–7,

Aug. 2020.

[16] A. Berardi et al., “Tools to assess the quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a

Information Classification: General

systematic review,” Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2020.

**This study is a systematic review on outcome measures for quality of life in people with

Parkinson's Disease

[17] J. Chandler, R. Churchill, T. Lasserson, D. Tovey, and J. Higgins, “Methodological standards

for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews,” http://editorial-

unit.cochrane.org/sites/editorial-

unit.cochrane.org/files/uploads/MECIR_conduct_standards%202.3%2002122013.pdf, 2013.

[18] A. Liberati et al., “The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-

analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration,” in

Journal of clinical epidemiology, 2009.

T

[19] M. Ruggieri et al., “Validated Fall Risk Assessment Tools for Use with Older Adults: A

IP

Systematic Review,” Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 331–353, Oct. 2018.

**This study is a systematic review on outcome measures for fall risk of adults.

[20] J. Noyes and S. Lewin, “Chapter 5: Extracting Qualitative Evidence,” Suppl. Guid. Incl.

R

Qual. Res. Cochrane Syst. Rev. Interv., 2011.

[21] S. Bates and E. Coren, “Systematic Map No.1: The Extent and Impact of Parental Mental

SC

Health Problems on Families and the Acceptability, Accessibility and Effectiveness of

Interventions.,” London SCIE, 2006.

[22] L. B. Mokkink et al., “The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy,

U

terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported

outcomes,” J. Clin. Epidemiol., 2010.

AN

* This is the checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

[23] L. B. Mokkink, C. B. Terwee, and D. L. Patrick, “COSMIN checklist manual,” COSMIN,

2012.

[24] J. C. Nunnally, Psychometric theory. 1979.

M

[25] H. Ford, P. Trigwell, and M. Johnson, “The nature of fatigue in multiple sclerosis,” J.

Psychosom. Res., 1998.

[26] S. Yamada et al., “Development of a short version of the motor fimTM for use in long-term

D

care settings,” J. Rehabil. Med., 2006.

TE

[27] J. Benito-León et al., “Impact of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: The fatigue Impact Scale for

Daily Use (D-FIS),” Mult. Scler., 2007.

[28] P. Michel et al., “A Multidimensional Computerized Adaptive Short-Form Quality of Life

Questionnaire Developed and Validated for Multiple Sclerosis,” Med. (United States), 2016.

EP

[29] H. Correia et al., “Spanish translation and linguistic validation of the quality of life in

neurological disorders (Neuro-QoL) measurement system,” Qual. Life Res., 2015.

[30] D. M. Miller et al., “Validating neuro-QoL short forms and targeted scales with people who

C

have multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler., 2015.

[31] L. D. Medina, S. Torres, E. Alvarez, B. Valdez, and K. V Nair, “Patient-reported outcomes in

AC

multiple sclerosis: Validation of the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-

QoLTM) short forms,” Mult. Scler. J. - Exp. Transl. Clin., 2019.

[32] R. C. Gershon et al., “Neuro-QOL: Quality of life item banks for adults with neurological

disorders: Item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population

testing,” Quality of Life Research. 2012.

[33] M. Ghajarzadeh et al., “Validity and reliability of the persian version of the PERception de la

scle’rose en plaques et de ses pousse’es questionnaire evaluating multiple sclerosis-related

quality of life,” Int. J. Prev. Med., 2016.

[34] A. Baroin et al., “Validation of a new quality of life scale related to multiple sclerosis and

relapses,” Qual. Life Res., 2013.

[35] R. A. Marrie and M. Goldman, “Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in

multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler., 2007.

Information Classification: General

[36] E. Chamot, I. Kister, and G. R. Cutter, “Item response theory-based measure of global

disability in multiple sclerosis derived from the Performance Scales and related items,” BMC

Neurol., 2014.

[37] C. E. Schwartz, T. Vollmer, and H. Lee, “Reliability and validity of two self-report measures

of impairment and disability for MS,” Neurology, 1999.

[38] E. Losonczi, K. Bencsik, C. Rajda, G. Lencsés, M. Török, and L. Vécsei, “Validation of the

Fatigue Impact Scale in Hungarian patients with multiple sclerosis,” Qual. Life Res., 2011.

[39] C. E. Schwartz, R. K. Bode, B. R. Quaranto, and T. Vollmer, “The symptom inventory

disability-specific short forms for multiple sclerosis: Construct validity, responsiveness, and

interpretation,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., 2012.

[40] C. E. Schwartz, R. K. Bode, R. Quaranto, and T. Vollmer, “The symptom inventory

T

disability-specific short forms for multiple sclerosis: Reliability and factor structure,” Arch.

IP

Phys. Med. Rehabil., 2012.

[41] R. Green, J. Kalina, R. Ford, K. Pandey, and I. Kister, “SymptoMScreen: A Tool for Rapid

Assessment of Symptom Severity in MS Across Multiple Domains,” Appl. Neuropsychol.,

R

2017.

[42] F. K.C. et al., “Validation of the SymptoMScreen with performance-based or clinician-

SC

assessed outcomes,” Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord., 2019.

[43] M. Heidari, S. M. Nabavi, M. Akbarfahim, M. Salehi, and M. Torabi-Nami, “Psychometric

properties of the Persian version of the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS-P) in patients with

[44] U

Multiple Sclerosis,” Iran. Rehabil. J., 2015.

Y. V. Gavrilov et al., “Validation of the Russian version of the Fatigue Impact Scale and

AN

Fatigue Severity Scale in multiple sclerosis patients,” Acta Neurol. Scand., 2018.

[45] L. B. Krupp, N. G. Larocca, J. Muir Nash, and A. D. Steinberg, “The fatigue severity scale:

Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus,” Arch.

Neurol., 1989.

M

[46] R. J. Mills, C. A. Young, R. S. Nicholas, J. F. Pallant, and A. Tennant, “Rasch analysis of the

Fatigue Severity Scale in multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler., 2009.

D

[47] K. Armutlu et al., “The validity and reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in Turkish

multiple sclerosis patients,” Int. J. Rehabil. Res., 2007.

TE

[48] D. Reske, R. Pukrop, K. Scheinig, W. F. Haupt, and H. F. Petereit, “Measuring fatigue in

patients with multiple sclerosis with standardized methods in German speaking areas,”

Fortschritte der Neurol. Psychiatr., 2006.

[49] H. I. Al-Sobayel et al., “Validation of an Arabic version of Fatigue Severity scale,” Saudi

EP

Med. J., 2016.

[50] P. O. Valko, C. L. Bassetti, K. E. Bloch, U. Held, and C. R. Baumann, “Validation of the

fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort,” Sleep, 2008.

C

[51] D. M. Meads, L. C. Doward, S. P. McKenna, J. Fisk, J. Twiss, and B. Eckert, “The

development and validation of the unidimensional fatigue impact scale (U-FIS),” Mult.

AC

Scler., 2009.

[52] Y. C. Learmonth, D. Dlugonski, L. A. Pilutti, B. M. Sandroff, R. Klaren, and R. W. Motl,

“Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact

Scale,” J. Neurol. Sci., 2013.

[53] A. Lerdal, S. Johansson, A. Kottorp, and L. Von Koch, “Psychometric properties of the

fatigue severity scale: Rasch analyses of responses in a Norwegian and a Swedish MS

cohort,” Mult. Scler., 2010.

[54] G. Salehpoor, S. Rezaei, and M. Hosseininezhad, “Psychometric properties of fatigue

severity scale in patients with multiple sclerosis,” J. Kerman Univ. Med. Sci., 2013.

[55] E. Rosti-Otajärvi, P. Hämäläinen, A. Wiksten, T. Hakkarainen, and J. Ruutiainen, “Validity

and reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in Finnish multiple sclerosis patients,” Brain

Behav., 2017.

Information Classification: General

[56] D. Bakalidou, E. K. Skordilis, S. Giannopoulos, E. Stamboulis, and K. Voumvourakis,

“Validity and reliability of the FSS in Greek MS patients,” Springerplus, 2013.

[57] N. Ghotbi, N. Nakhostin Ansari, S. Fetrosi, A. Shamili, H. Choobsaz, and H. Montazeri,

“Fatigue in Iranian patients with neurological conditions: An assessment with Persian fatigue

severity scale,” Heal. Sci. J., 2013.

[58] L. Hernandez-Ronquillo, F. Moien-Afshari, K. Knox, J. Britz, and J. F. Tellez-Zenteno,

“How to measure fatigue in epilepsy? The validation of three scales for clinical use,”

Epilepsy Res., 2011.

[59] M. B. Rietberg, E. E. H. Van Wegen, and G. Kwakkel, “Measuring fatigue in patients with

multiple sclerosis: Reproducibility, responsiveness and concurrent validity of three Dutch

self-report questionnaires,” Disabil. Rehabil., 2010.

T

[60] M. Ottonello, L. Pellicciari, A. Giordano, and C. Foti, “Rasch analysis of the fatigue severity

IP

scale in Italian subjects with multiple sclerosis,” J. Rehabil. Med., 2016.

[61] S. Rooney, D. A. McFadyen, D. L. Wood, D. F. Moffat, and P. L. Paul, “Minimally

important difference of the fatigue severity scale and modified fatigue impact scale in people

R

with multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord., 2019.

[62] L. C. Doward et al., “International development of the unidimensional fatigue impact scale

SC

(U-FIS),” Value Heal., 2010.

[63] S. Johansson, A. Kottorp, K. A. Lee, C. L. Gay, and A. Lerdal, “Can the Fatigue Severity

Scale 7-item version be used across different patient populations as a generic fatigue measure

U

- a comparative study using a Rasch model approach,” Health Qual. Life Outcomes, vol. 12,

no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2014.

AN

[64] D. Kos et al., “Assessing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Dutch Modified Fatigue Impact

Scale,” Acta Neurol. Belg., 2003.

[65] D. Kos, E. Kerckhofs, I. Carrea, R. Verza, M. Ramos, and J. Jansa, “Evaluation of the

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in four different European countries,” Mult. Scler., 2005.

M

[66] K. Pavan, K. Schmidt, B. Marangoni, M. F. Mendes, C. P. Tilbery, and S. Lianza, “Multiple

sclerosis: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the modified fatigue impact scale,” Arq.

D

Neuropsiquiatr., 2007.

[67] R. J. Mills, C. A. Young, J. F. Pallant, and A. Tennant, “Rasch analysis of the Modified

TE

Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) in multiple sclerosis,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 2010.

[68] M. Ghajarzadeh, R. Jalilian, G. Eskandari, M. Ali Sahraian, and A. Reza Azimi, “Validity

and reliability of Persian version of Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) questionnaire in

Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis,” Disabil. Rehabil., 2013.

EP

[69] M. H. Harirchian et al., “Evaluation of the Persian version of modified fatigue impact scale

in Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis.,” Iran. J. Neurol., 2013.

[70] D. Bakalidou, K. Voumvourakis, Z. Tsourti, E. Papageorgiou, A. Poulios, and S.

C

Giannopoulos, “Validity and reliability of the Greek version of the Modified Fatigue Impact

Scale in multiple sclerosis patients,” Int. J. Rehabil. Res., 2014.

AC

[71] H. Masuda et al., “Validation of the Japanese version of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale

and assessment of the effect of pain on scale responses in patients with multiple sclerosis,”

Clin. Exp. Neuroimmunol., 2015.

[72] G. E. A. Pust et al., “In search of distinct MS-related fatigue subtypes: results from a multi-

cohort analysis in 1.403 MS patients,” J. Neurol., 2019.

[73] J. Twiss, L. C. Doward, S. P. McKenna, and B. Eckert, “Interpreting scores on multiple

sclerosis-specific patient reported outcome measures (the PRIMUS and U-FIS),” Health

Qual. Life Outcomes, 2010.

[74] H. Khalil et al., “Cross cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of an Arabic version

of the modified fatigue impact scale in people with multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler. Relat.

Disord., 2020.

[75] N. Farran et al., “Factors affecting MS patients’ health-related quality of life and

Information Classification: General

measurement challenges in Lebanon and the MENA region,” Mult. Scler. J. - Exp. Transl.

Clin., 2020.

[76] A. S. Alawami and F. A. Abdulla, “Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the

modified fatigue impact scale in patients with multiple sclerosis,” Disabil. Rehabil., 2020.

[77] V. Meca-Lallana et al., “Assessing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Psychometric properties of

the five-item Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS-5),” Mult. Scler. J. - Exp. Transl. Clin.,

2019.

[78] A. Derksen, L. B. Mokkink, M. B. Rietberg, D. L. Knol, R. W. J. G. Ostelo, and B. M. J.

Uitdehaag, “Validation of a Dutch version of the Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MS) for

patients with multiple sclerosis in the Netherlands,” Qual. Life Res., 2013.

[79] J. Lopes, E. L. Lavado, and D. R. Kaimen-Maciel, “Validation of the Brazilian version of the

T

neurological fatigue index for multiple sclerosis,” Arq. Neuropsiquiatr., 2016.

IP

[80] R. J. Mills, C. A. Young, J. F. Pallant, and A. Tennant, “Development of a patient reported

outcome scale for fatigue in multiple sclerosis: The Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI-MS),”

Health Qual. Life Outcomes, 2010.

R

[81] R. J. Mills, M. Calabresi, A. Tennant, and C. A. Young, “Perceived changes and minimum

clinically important difference of the Neurological Fatigue Index for multiple sclerosis (NFI-

SC

MS),” Mult. Scler. J., 2013.

[82] I. K. Penner, C. Raselli, M. Stöcklin, K. Opwis, L. Kappos, and P. Calabrese, “The Fatigue

Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions (FSMC): Validation of a new instrument to assess

[83] U

multiple sclerosis-related fatigue,” Mult. Scler., 2009.

M. S. Oervik, T. Sejbaek, I. K. Penner, M. Roar, and M. Blaabjerg, “Validation of the fatigue

AN

scale for motor and cognitive functions in a danish multiple sclerosis cohort,” Mult. Scler.

Relat. Disord., 2017.

[84] J. D. Fisk, P. G. Ritvo, L. Ross, D. A. Haase, T. J. Marrie, and W. F. Schlech, “Measuring

the functional impact of fatigue: Initial validation of the fatigue impact scale,” Clin. Infect.

M

Dis., 1994.

[85] F. Motaharinezhad et al., “Validation of persian version of comprehensive fatigue assessment

D

battery for multiple sclerosis (CFAB-MS),” J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci., 2015.

[86] J. Chilcot, S. Norton, M. E. Kelly, and R. Moss-Morris, “The Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire

TE

is a valid and reliable measure of perceived fatigue severity in multiple sclerosis,” Mult.

Scler., 2016.

[87] L. A. Jason et al., “A screening instrument for chronic fatigue syndrome: Reliability and

validity,” J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr., 1997.

EP

[88] M. Worm-Smeitink et al., “The assessment of fatigue: Psychometric qualities and norms for

the Checklist individual strength,” J. Psychosom. Res., 2017.

[89] D. Kos et al., “Electronic visual analogue scales for pain, fatigue, anxiety and quality of life

C

in people with multiple sclerosis using smartphone and tablet: A reliability and feasibility

study,” Clin. Rehabil., 2017.

AC

[90] J. E. Schwartz, L. Jandorf, and L. B. Krupp, “The measurement of fatigue: A new

instrument,” J. Psychosom. Res., 1993.

[91] J. Iriarte, G. Katsamakis, and P. De Castro, “The fatigue descriptive scale (FDS): A useful

tool to evaluate fatigue in multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler., 1999.

[92] S. Hudgens, R. Schüler, J. Stokes, S. Eremenco, E. Hunsche, and T. P. Leist, “Development

and Validation of the FSIQ-RMS: A New Patient-Reported Questionnaire to Assess

Symptoms and Impacts of Fatigue in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis,” Value Heal., 2019.

[93] S. Behrangrad and A. Kordi Yoosefinejad, “Validity and reliability of the multidimensional

assessment of fatigue scale in Iranian patients with relapsing-remitting subtype of multiple

sclerosis,” Disabil. Rehabil., 2018.

[94] S. Thomas, P. Kersten, and P. W. Thomas, “The Multiple Sclerosis-Fatigue Self- Efficacy

(MS-FSE) scale: Initial validation,” Clin. Rehabil., 2014.

Information Classification: General

[95] V. Mathiowetz, “Test-retest reliability and convergent validity of the fatigue impact scale for

persons with multiple sclerosis,” Am. J. Occup. Ther., 2003.

[96] K. F. Cook, A. M. Bamer, T. S. Roddey, G. H. Kraft, J. Kim, and D. Amtmann, “A PROMIS

fatigue short form for use by individuals who have multiple sclerosis,” Qual. Life Res., 2012.

[97] R. A. Marrie, G. Cutter, T. Tyry, O. Hadjimichael, D. Campagnolo, and T. Vollmer,

“Validation of the NARCOMS Registry: Fatique assessment,” Mult. Scler., 2005.

[98] S. Johansson, C. Ytterberg, B. Back, L. W. Holmqvist, and L. von Koch, “The Swedish

Occupational Fatigue Inventory in people with multiple sclerosis,” J. Rehabil. Med., 2008.

[99] D. Kos, G. Nagels, M. B. D’Hooghe, M. Duportail, and E. Kerckhofs, “A rapid screening

tool for fatigue impact in multiple sclerosis,” BMC Neurol., 2006.

[100] P. Flachenecker, G. Müller, H. König, H. Meissner, K. V Toyka, and P. Rieckmann,

T

“["Fatigue" in multiple sclerosis. Development and and validation of the ‘Würzburger

IP

Fatigue Inventory for MS’].,” Nervenarzt, 2006.

[101] P. Flachenecker, H. König, H. Meissner, G. Müller, and P. Rieckmann, “Fatigue bei multiper

sklerose: Validierung des Würzburger Erschöpfungs-Inventars bei Multipler Sklerose

R

(WEIMUS),” Neurol. und Rehabil., 2008.

[102] A. S. Chua et al., “Patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis: Relationships among

SC

existing scales and the development of a brief measure,” Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord., 2015.

[103] L. S. Matza, K. D. Stewart, G. Phillips, P. Delio, and R. T. Naismith, “Development of a

brief clinician-reported outcome measure of multiple sclerosis signs and symptoms: The

U

Clinician Rating of Multiple Sclerosis (CRoMS),” Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord., 2019.

[104] D. F. Cella et al., “Validation of the functional assessment of multiple sclerosis quality of life

AN

instrument,” Neurology, 1996.

[105] C. H. Chang et al., “Quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients in Spain,” Mult. Scler., 2002.

[106] G. Flensner, E. Anna-Christina, and O. Söderhamn, “Reliability and validity of the Swedish

version of the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS),” Scand. J. Occup. Ther., 2005.

M

[107] M. F. Mendes, S. Balsimelli, G. Stangehaus, and C. P. Tilbery, “Validation of the functional

assessment of multiple sclerosis quality of life instrument in a Portuguese language,” Arq.

D

Neuropsiquiatr., 2004.

[108] F. Patti, P. Russo, A. Pappalardo, F. Macchia, L. Civalleri, and A. Paolillo, “Predictors of

TE

quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis: An Italian cross-sectional study,” J.

Neurol. Sci., 2007.

[109] J. Sørensen et al., “Validation of the Danish Version of Functional Assessment of Multiple

Sclerosis: A Quality of Life Instrument,” Mult. Scler. Int., 2011.

EP

[110] I. Ensari, R. W. Motl, and E. McAuley, “Structural and construct validity of the Leeds

Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life scale,” Qual. Life Res., 2016.

[111] H. L. Ford, E. Gerry, A. Tennant, D. Whalley, R. Haigh, and M. H. Johnson, “Developing a

C

disease-specific quality of life measure for people with multiple sclerosis,” Clin. Rehabil.,

2001.

AC

[112] D. I. Akbiyik et al., “The validity and test-retest reliability of the Leeds multiple sclerosis

quality of life scale in Turkish patients,” Int. J. Rehabil. Res., 2009.

[113] J. Greenhalgh, “An assessment of the feasibility and utility of the MS Symptom and Impact

Diary (MSSID),” Qual. Life Res., 2005.

[114] B. G. Vickrey, R. D. Hays, R. Harooni, L. W. Myers, and G. W. Ellison, “A health-related

quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis,” Qual. Life Res., 1995.

[115] A. Solari et al., “Validation of Italian multiple sclerosis quality of life 54 questionnaire,” J.

Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 1999.

[116] A. Miller and S. Dishon, “Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: Psychometric

analysis of inventories,” Mult. Scler., 2005.

[117] K. Armutlu et al., “Psychometric study of Turkish version of Fatigue Impact Scale in

multiple sclerosis patients,” J. Neurol. Sci., 2007.

Information Classification: General

[118] I. E. et al., “Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of multiple sclerosis quality of life

questionnaire (MSQOL-54) in a Turkish multiple sclerosis sample,” J. Neurol. Sci., 2006.

[119] S. Heiskanen, P. Meriläinen, and A. M. Pietilä, “Health-related quality of life - Testing the

reliability of the MSQOL-54 instrument among MS patients,” Scandinavian Journal of

Caring Sciences. 2007.

[120] T. Pekmezovic, D. Kisic Tepavcevic, J. Kostic, and J. Drulovic, “Validation and cross-

cultural adaptation of the disease-specific questionnaire MSQOL-54 in Serbian multiple

sclerosis patients sample,” Qual. Life Res., 2007.

[121] J. Füvesi et al., “Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the ‘Multiple Sclerosis Quality

of Life Instrument’ in Hungarian,” Mult. Scler., 2008.

[122] K. El Alaoui Taoussi, E. Ait Ben Haddou, A. Benomar, R. Abouqal, and M. Yahyaoui,

T

“Quality of life and multiple sclerosis: Arabic language translation and transcultural

IP

adaptation of ‘mSQOL-54,’” Rev. Neurol. (Paris)., 2012.

[123] T. Catic, J. Culig, E. Suljic, A. Masic, and R. Gojak, “Validation of the Disease-specific

Questionnaire MSQoL-54 in Bosnia and Herzegovina Multiple Sclerosis Patients Sample,”

R

Med. Arch. (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina), 2017.

[124] R. Estiasari et al., “Validation of the Indonesian version of multiple sclerosis quality of life-

SC

54 (MSQOL-54 INA) questionnaire,” Health Qual. Life Outcomes, 2019.

[125] R. Rosato et al., “Development of a short version of MSQOL-54 using factor analysis and

item response theory,” PLoS One, 2016.

U

[126] G. Baker, K. P. S. Nair, K. Baster, R. Rosato, and A. Solari, “Reliability and acceptability of

the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-29 questionnaire in an English-speaking cohort,” Mult.

AN

Scler. J., 2019.

[127] B. Stern, T. Hojs Fabjan, K. Rener-Sitar, and L. Zaletel-Kragelj, “Validation of the Slovenian

version of multiple sclerosis quality of life (MSQOL-54) instrument,” Zdr. Varst., 2017.

[128] M. Debouverie, S. Pittion-Vouyovitch, S. Louis, and F. Guillemin, “Validity of a French

M

version of the fatigue impact scale in multiple sclerosis,” Mult. Scler., 2007.

[129] R. Rosato et al., “eMSQOL-29: Prospective validation of the abbreviated, electronic version

D

of MSQOL-54,” Mult. Scler. J., 2019.

[130] Y. Zhang, B. V. Taylor, S. Simpson, L. Blizzard, A. J. Palmer, and I. van der Mei,

TE

“Validation of 0–10 MS symptom scores in the Australian multiple sclerosis longitudinal

study,” Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord., 2020.

[131] M. C. Simeoni et al., “Validation of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life

questionnaire,” Mult. Scler., 2008.

EP

[132] N. Triantafyllou, A. Triantafillou, and G. Tsivgoulis, “Validity and reliability of the greek

version of the multiple sclerosis international quality-of-life questionnaire,” J. Clin. Neurol.,

2009.

C

[133] K. Baumstarck-Barrau, J. Pelletier, M. C. Simeoni, and P. Auquier, “French validation of the

Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire,” Rev. Neurol. (Paris)., 2011.

AC

[134] O. Fernández et al., “Validation of the spanish version of the multiple sclerosis international

quality of life (musiqol) questionnaire,” BMC Neurol., 2011.

[135] A. Jamroz-Wiśniewska, Z. Stelmasiak, and H. Bartosik-Psujek, “Validation analysis of the

Polish version of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life Questionnaire

(MusiQoL),” Neurol. Neurochir. Pol., 2011.

[136] J. Thumboo, A. Seah, C. T. Tan, B. S. Singhal, and B. Ong, “Asian adaptation and validation

of an English version of the multiple sclerosis international quality of life questionnaire

(MusiQoL),” Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore, 2011.

[137] A. G. Beiske, K. Baumstarck, R. M. Nilsen, and M. C. Simeoni, “Validation of the multiple

sclerosis international quality of life (MusiQoL) questionnaire in Norwegian patients,” Acta

Neurol. Scand., 2012.

[138] S. Y. Huh et al., “Validity of Korean versions of the multiple sclerosis impact scale and the

Information Classification: General

multiple sclerosis international quality of life questionnaire,” J. Clin. Neurol., 2014.

[139] P. Gompertz, P. Pound, and S. Ebrahim, “Validity of the extended activities of daily living

scale,” Clin. Rehabil., 1994.

[140] J. Lopes, E. L. Lavado, A. P. Kallaur, S. R. de Oliveira, E. M. V. Reiche, and D. R. Kaimen-

Maciel, “Assessment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: methodological quality of adapted

original versions available in Brazil of self-report instruments,” Fisioter. e Pesqui., 2014.

[141] D. AER, P. CJ, G. JRF, and L. PA, “Development and validation of the Nottingham Leisure

Questionnaire (NLQ),” Clin. Rehabil., 2001.

[142] G. M., J. R., E. G., A. S. M., and R. A. A., “Validity and reliability of Persian version of

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) questionnaire in Iranian patients with multiple

sclerosis.,” Disabil. Rehabil., 2013.

T

[143] B. G. Vickrey, R. D. Hays, B. J. Genovese, L. W. Myers, and G. W. Ellison, “Comparison of

IP

a generic to disease-targeted health-related quality-of-life measures for multiple sclerosis,” J.

Clin. Epidemiol., 1997.

[144] L. B. Mokkink et al., “The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of

R

studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An

international Delphi study,” Qual. Life Res., 2010.

SC

[145] L. B. Mokkink et al., “The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of

studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content,” BMC Med. Res.

Methodol., 2010.

U

[146] J. F. Kurtzke, “Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability

status scale (EDSS),” Neurology, 1983.

AN

[147] J. Iriarte and P. Castro, “Correlation between sympotom fatigue and muscular fatigue in

multiple sclerosis,” Eur. J. Neurol., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 579–585, Nov. 1998.

[148] N. E. Carlozzi, N. R. Boileau, S. L. Murphy, T. J. Braley, and A. L. Kratz, “Validation of the

Pittsburgh Fatigability Scale in a mixed sample of adults with and without chronic

M

conditions,” J. Health Psychol., 2019.

[149] F. P., K. H., M. H., M. G., and R. P., “Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Validation of the

D

WEIMuS scale (‘Wurzburger Erschopfungs-Inventar bei Multipler Sklerose’),” Neurologie

und Rehabilitation. 2008.

TE

[150] J. Greenhalgh, H. Ford, A. F. Long, and K. Hurst, “The MS Symptom and Impact Diary

(MSSID): Psychometric evaluation of a new instrument to measure the day to day impact of

multiple sclerosis,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 2004.

[151] H. Ghaem, A. Haghighi, P. Jafari, and A. Nikseresht, “Validity and reliability of the Persian

EP

version of the multiple sclerosis quality of life questionnaire,” Neurol. India, 2007.

C

AC

Information Classification: General

Descriptio Reccomendation

Name Languages ADM Chacacteristics MS type Setting

Assessment tools specific for Fatigue in MS

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) [44]– English, Turkish, German, Arabic, Norwegian, I/SR The Fatigue Severity Scale is a 9-item scale which measures the severity of PP, RR, Research and Clinical

[49], [52]–[61] Swedish, Persian, Russian, Finnish, Greek, fatigue and its effect on a person's activities and lifestyle in patients with a SP

Dutch, Italian variety of disorders. The short version si composed by 7 items

T

Fatigue Severity Scale-7item (FSS- Swedish I PP, RR, Research and Clinical

IP

7) [63] SP

Unidimensional Fatigue Impact French-(Canada) English (Canada), French, SR The Unidimensional Fatigue Impact Scale (U-FIS) is a disease-specific PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Scale (U-FIS) [51], [62], [73] German, Italian. Spanish, Swedish, English patient-reported outcome measure which measures the impact of multiple SP

R

(USA) sclerosis related fatigue. It is a 22-item unidimensional scale which is based

on needs-based quality of life theory.

SC

Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) [38], English, Swedish, Turkish, French, Hungarian, I/SR The FIS was developed to assess the symptom of fatigue as part of an PP, RR, Research and Clinical

[43], [44], [84], [95], [106], [117], Persian, Russian underlying chronic disease or condition. Consisting of 40 items, the SP

[128] instrument evaluates the effect of fatigue on three domains of daily life:

cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and psychoso- cial functioning.

U

Daily Fatigue. Impact Scale (D-FIS) Spanish SR The D-FIS is an eight-item version of the FIS designed for daily use in PP, RR, Clinical

[27] clinical practice. It comprises three items from the physical domain, four SP

AN

items from the cognitive domain, and one item from the psychosocial domain.

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale Dutch, Italian, Spanish, French, Slovenian, I/SR The MFIS is a modified form of the Fatigue Impact Scale (Fisk et al, 1994b) PP, RR, Research and Clinical

(MFIS) [52], [59], [61], [64]–[72], Portuguese (Brazil), Polish, English, Persian, based on items derived from interviews with MS patients concerning how SP

[74], [76] Greek, Japanese, Arabic, German fatigue impacts their lives.

M

Modified Fatigue Impact Scale – Spagnish SR PP, RR, Research and Clinical

5item (M-FIS-5)[77] SP

Neurological Fatigue Index - Dutch, Portuguese (Brazil), English, German I/SR The NFI-MS consists of 23 items in four subscales of Physical (8 items), PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Multiple Sclerosis ( NFI-MS) [78]– Cognitive (4 items), Relief by diurnal sleep or rest (6 items) and Abnormal SP

D

[81] nocturnal sleep and sleepiness (5 items)

German , Danish I/SR The FSMC is a 20-item sclae developed as a measure of cognitive and motor PP, RR, Clinical

Fatigue Scale for Motor and

Cognitive Functions (FSMC) [72],

TE fatigue for people with MS. A Likert-type 5-point scale (ranging from 'does

not apply at all' to 'applies completely')

SP

[82], [83]

Comprehensive Fatigue Assessment Persian - The CFAB-MS, in addition to assessment of the fatigue, evaluates factors PP, RR, Clinical

EP

Battery for Multiple Sclerosis related to fatigue, including sleep, pain, mobility, stress, anxiety, mood and SP

(CFAB-MS) [85] fatigue management skills.

Chalder fatigue scale (CFQ) [72], English, German SR The Chalder fatigue scale (CFQ) is a questionnaire created to measure the PP, RR, Clinical

[86] severity of tiredness in fatiguing illnesses. SP

C

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome English I The CFS SQ Symptom Inventory consisted of 19items assessing fatigue and PP, SP Clinical

Screening Questionnaire (CFS illness-related symptoms during the previousmonth.

AC

SQ) [87]

Checklist Individual Strength Dutch SR/I The CIS20R contains 20 statements, scored on a seven-point scale (1-7), PP, SP Clinical

(CIS20R) [59] reflecting four aspects of fatigue: subjective feeling of fatigue, reduction of

concentration, reduction of motivation, and reduction of physical activity.

Fatigue Assessment Inventory English - The 29-item scale is designed to evaluate four domains of fatigue: its severity, PP, RR, Clinical

(FAI) [90] pervasiveness, associated consequences, and response to sleep. SP

Fatigue Descriptive Scale (FDS) Spanish I FDS is a five-category interview-based scale used to assess fatigue in three PP, RR, Clinical

[147] categories: fatigue associated with asthenia; fatigue with exercise; fatigue with SP

worsening symptoms

Information Classification: General

Fatigue Symptoms and Impacts English I The FSIQ-RMS measures fatigue symptoms and impacts in relapsing multiple RR Clinical

Questionnaire - Relapsing Multiple sclerosis

Sclerosis (FSIQ-RMS) [92]

Multidimensional Assessment of Persian SR The MAF is a 16 item scale that measures fatigue according to four PP, RR, Clinical

Fatigue (MAF) [93] dimensions: degree and severity, distress that it causes, timing of fatigue (over SP

the past week, when it occurred and any changes), and its impact on various

activities of daily living (household chores, cooking, bathing, dressing,

working, socializing, sexual activity, leisure and recreation, shopping,

walking, and exercising).

T

Multiple Sclerosis-Fatigue Self– English SR The MS-FSE is composed by 6 items consists of a 10-point numeric rating PP, RR, Clinical

Efficacy (MS-FSE) [94] scale (ranging from 10-100) SP

IP

Pittsburgh Fatigability Scale (PFS) English SR The 10-item PFS physical fatigability score is a valid and reliable measure of SP Clinical

[148] perceived fatigability in older adults and can serve as an adjunct to

performance-based fatigability measures for identifying older adults at risk of

R

mobility limitation in clinical and research settings.

PROMIS-Fatigue English - The PROMIS-Fatigue PP, SP Clinical

SC

MS[96] MS is a 10-item scale designed for use across chronic

Diseases asking “How often” people experience fatigue in activities of daily

living

Swedish Occupational Fatigue Svedish I The SOFI was developed to measure subjective dimensions of work-related PP, RR, Clinical

U

Inventory SOFI[98] fatigue. The instrument consists of 20 items, in which feelings of being tired SP

are graded from 0 (not had such feelings at all) to 6 (had such feelings to a

AN

very high degree) (23).

W ürzburger Erschöpfungs- German SR The WEIMuS consists of 17 items with 5 categories each (0-4) resulting in a PP, RR, Clinical

Inventar bei Multipler Sklerose total sum score of 68, with subscores for cognitive (0-36) and physical (0-32) SP

(WEIMuS)[100], [149] fatigue.

M

Assessment tools including a Fatigue domain in the questionnaire

Brief patient-reported outcome for English I The BPRO-MS combines MS-related psychosocial and quality of life domains PP, RR, Clinical

D

MS (BPRO-MS) [102] SP

Clinician Rating of Multiple English I The CRoMS is a brief clinician-reported outcome measure of multiple PP, RR, Clinical

Sclerosis (CRoMS) [103]

Functional Assessment of Multiple

TE

English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Danish I/SR

sclerosis signs and symptoms:

The FAMS allows assessment of overall physical health as reported by

SP

PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Sclerosis (FAMS) [104], [105], patients SP

[107]–[109]

EP

Leeds Multiple Sclerosis Quality of English, Turkish I/SR The LMSQOL IS an 8-item, unidimensional disease-targeted measure of PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Life (LMSQOL) [110]–[112] quality of life (QOL) SP

C

MS Symptom and Impact Diary English SR The majority of items in the MSSID focus on the physicalsymptoms of MS PP, RR, Clinical

(MSSID) [150] and their impact on daily activities, which issimilar to the item content of the SP

AC

MSIS-29.9However, like theMSIS-29, it also includes important items that

address theemotional impact of the condition. The MSSID consists ofthree

factors that measure mobility, the cognitive andemotional aspects of fatigue,

and the overall impact of MS

MSQOL-54 [114]–[116], [118]– English, Italian, Hebrew, Turkish, Finnish, SR/ The MSQOL is one of the most wide used disease specific instrument for PP, RR, Research and Clinical

[124], [127], [151] Persian, Serbian, Hungarian, Arabic, Bosnian, I measuring health related quality of life SP

Indonesian, Slovenian

MSQOL-54 Italian SR PP, RR, Research and Clinical

SF [125] SP

Information Classification: General

eMSQOL-29 SF [126], [129] Italian, English SR PP, RR, Research and Clinical

SP

Multiple Sclerosis International Spanish (Argentina), French, German, Greek, SR MusiQoL)questionnaire, a multi-dimensional, self-administered questionnaire, PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Quality of Life questionnaire Hebrew, Italian, Norwegian, Russian, Spanish, is a valid and reliable multidimensional, 31-item questionnaire for assessing SP

(MusiQoL) [75], [131], [132], [135], Turkish, English, Arabic, Spanish, English disease-specific QoL in people with MS

[137], [138] (Singapore, Malaysia, India), Polish, Korean

Multiple Sclerosis International English I PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Quality of Life questionnaire SP

T

multidimensional computerized

adaptive short-form questionnaire

IP

(MusiQoL-MCAT) [28]

Quality of Life in Neurological English, Spanish SR The NeuroQOL is a self-report of health related quality of life in 17 domains PP, RR, Research and Clinical

Disorders (Neuro-QoL) [29], [32] and sub-domains for adults, is a measurement system that evaluates and SP

R