Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023

Uploaded by

pau.reccCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023

Uploaded by

pau.reccCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure and obstetric and birth

outcomes: a Danish nationwide cohort study

from 1996 to 2018

Marcella Broccia, Bo Mølholm Hansen, Julie Marie Winckler, Thomas Larsen, Katrine Strandberg-Larsen, Christian Torp-Pedersen,

Ulrik Schiøler Kesmodel

Summary

Background Heavy alcohol use during pregnancy can harm the fetus, but the relation to most obstetric outcomes Lancet Public Health 2023;

remains unclear. We therefore aimed to describe maternal characteristics and estimate the association between heavy 8: e28–35

prenatal alcohol exposure and 22 adverse obstetric and birth outcomes. See Comment page e4

Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Aalborg

Methods We carried out a Danish nationwide register-based historical cohort study, including all singleton births

University Hospital, Aalborg,

from Jan 1, 1996, to Dec 31, 2018. Births of women who had emigrated to Denmark were excluded from the study due Denmark (M Broccia MD,

to missing data and women who migrated within 1 year before or during pregnancy were also excluded due to loss to Prof U S Kesmodel PhD);

follow-up. Data were extracted from the Danish Medical Birth Register, the Danish National Patient Registry, the Department of Clinical

Medicine, Aalborg University,

Danish National Prescription Registry, the Danish Civil Registration System, and the Population Education Register.

Aalborg, Denmark (M Broccia,

Logistic regression models were used to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of obstetric and birth Prof U S Kesmodel); Department

outcomes. Heavy alcohol use was defined by hospital contacts for alcohol-attributable diagnoses given to the mother, of Cardiology (M Broccia,

her infant, or both, or maternal redeemed prescriptions for drugs to treat alcohol dependence within 1 year before or J M Winckler MScPH,

Prof C Torp-Pedersen DrMedSci)

during pregnancy.

and Department of Paediatrics

and Adolescent Medicine

Findings Of 1 191 295 included births, 4823 (0·40%) were defined as heavily alcohol-exposed and 1 186 472 were (B M Hansen PhD),

categorised as a reference group with no identified heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Heavy-alcohol-exposed births Nordsjællands Hospital,

Hillerød, Denmark; Section of

more often had mothers with psychiatric diagnoses (49·8% vs 9·6%), substance use (22·0% vs 0·4%), tobacco use Epidemiology (J M Winckler,

(64·3% vs 15·8%), and low educational level (64·1% vs 17·6%) than did the reference group. For heavy-alcohol- K Strandberg-Larsen PhD),

exposed births, significantly increased adjusted ORs were found for small for gestational age (OR 2·20 [95% CI Department of Public Health

1·97–2·45]), preterm birth (OR 1·32 [1·19–1·46]), haemorrhage in late pregnancy (OR 1·25 [1·05–1·49]), and preterm (Prof C Torp-Pedersen),

University of Copenhagen,

prelabour rupture of membranes (OR 1·18 [1·00–1·39]). Decreased adjusted ORs were found for postpartum Copenhagen, Denmark;

haemorrhage (500–999 mL; OR 0·80 [95% CI 0·69–0·93]), gestational diabetes (OR 0·81 [0·67–0·99]), planned Lillebaelt Hospital, Kolding,

caesarean section (OR 0·82 [0·72–0·94]), pre-eclampsia and eclampsia (OR 0·83 [0·71–0·96]), and abnormalities of Denmark (T Larsen CMO);

forces of labour (OR 0·92 [0·86–0·99]). Department of Paediatrics and

Adolescent Medicine,

Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

Interpretation Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with adverse obstetric and birth outcomes and high University Hospital, Denmark

proportions of maternal low educational level, psychiatric disease, and lifestyle risk behaviours. These findings (M Broccia)

highlight a need for holistic public health programmes and policy attention on improving pre-conceptional care and Correspondence to:

antenatal care. Dr Marcella Broccia, Department

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Aalborg University Hospital,

Funding The Obel Family Foundation, The Health Foundation, TrygFonden, Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, 9000 Aalborg, Denmark

The North Denmark Region Health Science and Research Foundation, Holms Memorial Foundation, Dagmar marcellabroccia@hotmaill.com

Marshalls Foundation, the A.P. Møller Foundation, King Christian X Foundation, Torben and Alice Frimodts

Foundation, the Axel and Eva Kastrup-Nielsens Foundation, the A.V. Lykfeldts Foundation.

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND

4.0 license.

Introduction Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure can result in

Health protection agencies, national health authorities, impaired fetal development4–6 and fetal alcohol spectrum

and clinical guidelines advocate abstinence from alcohol disorders,4 and has been established as a risk factor for

during pregnancy.1 Alcohol use among women of fetal death,5,7 small for gestational age,5,6 and preterm

reproductive age is common, and globally nearly 10% birth.5–7 However, there is uncertainty regarding other

of women consume alcohol during pregnancy.2 In obstetric and birth complications, and many obstetric

Denmark, prevalence of heavy prenatal alcohol con outcomes are left unexamined. A meta-analysis with

sumption was estimated to be between 0·1% seven studies reported no association between alcohol

and 0·4% from 1995 to 2009.3 and gestational diabetes.8 However, the included studies

www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023 e28

Articles

Research in context

Evidence before this study association between heavy prenatal alcohol exposure and

Alcohol can interfere with normal fetal development. Heavy obstetric and birth outcomes. This study provides new insight

alcohol drinking during pregnancy is associated with small for into the pattern of 22 adverse obstetric and birth outcomes.

gestational age, low birthweight, preterm birth, and fetal Most outcomes showed an uncertain association after

death. Alcohol use during pregnancy is common in many adjustment; these were anaemia, Apgar score of less than

countries, but the effect of heavy alcohol drinking on most 7 after 5 min, emergency caesarean section, forceps or vacuum

obstetric outcomes and the related maternal characteristics delivery, haemorrhage in early pregnancy, liver disorders,

are less clear. We searched PubMed from inception to perinatal mortality, placenta praevia, placental abruption, post-

Dec 13, 2021, for studies investigating the association partum haemorrhage (>999 mL), retained placenta and

between heavy prenatal alcohol exposure and obstetric and membranes, stillbirth, and uterine rupture. Our findings provide

birth conditions. The search terms were “((pregnancy OR important knowledge of the profile of pregnant women with

obstetrical OR neonatal) OR (pregnanc* OR obstetric* OR heavy alcohol use and show a strong association with maternal

neonatal*)) AND (heavy AND alcohol)” with no language psychiatric disease, substance use, and tobacco use.

restrictions. The search generated 939 studies. The identified

Implications of all the available evidence

articles predominantly investigated the association between

Heavy alcohol use during pregnancy is a high-risk behavior

prenatal alcohol exposure and birth outcomes.

associated with maternal vulnerability and adverse obstetric and

Methodological heterogeneity among studies, design

birth outcomes, which endanger both maternal and fetal health.

limitations such as recall bias, and a wide range of publication

The association between heavy alcohol exposure and both small

years were observed. Thus, the extent of obstetric and birth

for gestational age and preterm birth is marked, both of which

complications related to heavy alcohol exposure is uncertain

are precursors of infant morbidity and mortality. Protecting

and remains to be comprehensively studied with objective,

maternal and children´s health begins pre-conceptionally. Heavy

large-scale data.

alcohol use during pregnancy and the associated risks require

Added value of this study immediate action and persistent attention in antenatal

We used Danish nationwide registries including more than planning, in addition to intervention at all levels.

1·1 million births to describe maternal characteristics and the

had contrary results.8 Another meta-analysis of placenta- allowing for a broad insight; and (2) describe maternal

related outcomes found increased odds for placental characteristics of heavy alcohol users.

abruption, but no association with placenta praevia.9

Most of the included studies investigating placenta- Methods

related outcomes relied on maternal self-reported Study design and participants

information on alcohol consumption and some studies This historical cohort study is based on Danish

did not include a thorough analysis of potential nationwide registries.11 The Danish welfare system offers

confounders.9 Further more, one study identified an pregnant women free antenatal care, including three

association between low or moderate alcohol exposure general practitioner visits, four midwife visits, and

and placenta accreta, while another study found no ultrasound scans in gestational weeks 13–14 and 18–20.

association between heavy alcohol exposure and pre- Our study population comprised singleton births from

eclampsia.9 Jan 1, 1996, to Dec 31, 2018. We excluded births of women

Maternal risk factors for obstetric and birth outcomes who emigrated to Denmark due to a large proportion of

are multidimensional. Alcohol use during pregnancy has missing data and women who migrated within 1 year

been related to risk behaviours such as co-use of before or during pregnancy due to loss to follow-up

See Online for appendix substances and tobacco, both of which can affect obstetric (appendix p 2). In accordance with the General Data

and birth outcomes.10 Furthermore, maternal age, parity, Protection Regulation, approval to use the data sources

and concurrent maternal somatic and psychiatric for research purposes was granted by the data institute in

diseases are examples of risk factors for adverse obstetric the Capital Region of Denmark (approval number:

and birth outcomes. P-2019-280). In Denmark, ethical committee approval or

The existing evidence is based on studies with varying patient consent are not required for register-based

sample size and range of publication years and evidence studies.

based on a more contemporary population with access to

modern antenatal care strategies is scarce. We therefore Procedures

aimed to: (1) investigate the association between heavy All residents in Denmark receive a unique Civil Personal

prenatal alcohol exposure and a wide range of obstetric Registration number for administrative purposes (eg, for

and birth outcomes within a nationwide cohort, thus contact with the health-care system).12,13 We linked each

e29 www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023

Articles

birth record to the mother using this Civil Personal biparietal diameter, including crown–rump length

Registration number and relevant register data. since 2008.23 Missing data on gestational age was replaced

We obtained data from the Danish Medical Birth with 40 weeks’ gestation.

Register concerning date of birth, stillbirth, fetal sex,

gestational age, birthweight, Apgar score, and maternal Outcomes and covariates

data on age at birth, parity, tobacco use, and body-mass We examined 22 outcomes. Three outcomes were

index (BMI) at the first antenatal care visit.14 The Danish analysed with exclusion of stillbirths: (1) Apgar score of

National Patient Registry contains information on less than 7 after 5 min (Apgar <7/5), which was a proxy

hospital admissions since 1977, and outpatient and for perinatal asphyxia. Recorded Apgar scores contained

inpatient hospital contacts since 1995.15 From this registry errors in 1996; therefore we used data from 1997 to 2018.

we obtained data on outpatient and inpatient hospital (2) Small for gestational age was a composite of the

contacts, diagnosis codes according to the International diagnosis SGA (ICD-10: P05·1) or a birth weight of less

Classification of Diseases (8th Revision and 10th Revision than 2 standard deviations (SDs) below the mean for

[ICD-10]), and surgical procedure codes according to the gestational age according to the ultrasound-based

Danish version of the Nordic Medico-Statistical reference curve commonly used in Denmark.24 Ges

Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures.16 tational age of less than 25 + 0 weeks or more than

Information on redeemed prescriptions from Danish 42 + 6 weeks, and extreme small for gestational age curve

pharmacies was extracted from the Danish National values (SD +/–4 from the mean) were excluded to avoid

Prescription Registry according to the Anatomical misclassification (appendix p 10). (3) Preterm birth was a

Therapeutic Chemical codes.17 We obtained data on composite of the diagnosis preterm infant (ICD-10:

ethnicity based on the participants’ own or parents’ P07.3, P07.2) or gestational age of less than 37 weeks. In

country of birth from the Danish Civil Registration Denmark, livebirth is defined as any signs of life after

System.12 Data on maternal highest educational level at complete expulsion or extraction from the uterus,

delivery was extracted from the Population Education irrespective of pregnancy duration.25 Stillbirth was

Register.18 The data were collected continuously at the defined as pregnancy loss or death at or after 28 weeks

time of use of health-care services and directly transferred before 2004, and from 2004, as pregnancy loss or death at

into the registers used. The Danish registries have been or after 22 weeks’ gestation.25 Perinatal mortality was

validated, previously described in detail, and are generally defined as stillbirth and death within 7 days after birth.

of high quality and completeness.13 Gestational diabetes was diagnosed at a risk factor-based

Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure was our primary screening by a 75 g oral glucose challenge test with a 2-h

interest. As a proxy measure, we used pharmacological venous or capillary plasma glucose of 9·0 mmol/L or

treatment of alcohol dependence and clinically higher. Pre-eclampsia was defined as systolic blood

recognised conditions, by definition, caused directly by pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher and diastolic blood

alcohol use, defined as the presence of one or more of the pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher, accompanied by

following criteria: (1) maternal contact with a hospital proteinuria (≥0·3 g/day or ≥1 + [20 mg/dl] on a urine

with a 100% alcohol-attributable diagnosis within 1 year dipstick). Haemorrhage in early pregnancy was defined

before or during pregnancy; (2) redeemed prescription as bleeding before 11 weeks and 6 days of gestation, and

for drugs to treat maternal alcohol dependence within haemorrhage in late pregnancy was defined as bleeding

1 year before or during pregnancy; (3) a prenatal alcohol- from 12 completed weeks onwards. Postpartum

related diagnosis given to the child after their birth haemorrhage was defined as 500–999 mL and more than

(appendix p 6). The 100% alcohol-attributable diagnoses 999 mL of blood loss within 24 h after delivery. Blood loss

cover acute and chronic conditions according to estimation was measured by volume, as has been

pre-existing lists selected by experts on alcohol and based standard procedure since 2012. Preterm pre-labour

on previous evidence.19,20 Pregnant women were rupture of membranes (PPROM) was defined as rupture

systematically screened for alcohol use at the first of membranes before labour before 37 weeks. Anaemia

antenatal care visit. If excessive use was reported, the was defined as haemoglobin concentrations of less than

woman was referred to hospital and given a 100% alcohol- 110 g/l and approximately 6·8 mmol/l in the first

attributable diagnosis. Exposure within 1 year before the trimester and less than 105 g/l and approximately

index pregnancy was included as pre-pregnancy drinking 6·5 mmol/l in the second and third trimesters.

has been shown as a strong predictor of pregnancy Emergency caesarean section was performed within 8 h

drinking.21 An Australian study showed that about 51% of after a decision was made that it was required, and

mothers had a recorded alcohol-attributable diagnosis planned caesarean section scheduled 8 hours after the

both before and during pregnancy.22 The pregnancy decision. Any use of vacuum or forceps during delivery

period was estimated by subtracting recorded gestational was evaluated as a composite endpoint. Abnormalities of

age at birth from the date of birth. Ultrasound pregnancy forces of labour included hypertonic uterine dysfunction,

dating has, before 2005, been performed in weeks 17–18 labour dystocia, labour weakness, and failed induction of

and since 2005 in weeks 11–14 by measurement of labour. Uterine rupture included both incomplete and

www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023 e30

Articles

myometrium, and placental percreta with visible growth

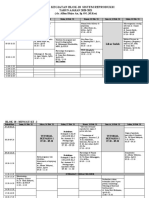

Total (n=1 191 295) Reference group Heavy-alcohol-

(n=1 186 472) exposed group through the uterine wall. Furthermore, we examined

(n=4823) placental abruption, placenta praevia, and liver disorders

Fetal sex* related to pregnancy. Additional ICD-10 and surgical

Female 578 179/1 188 503 (48·6%) 575 862/1 183 704 (48·6%) 2317/4799 (48·3%) procedure codes outcome definitions are listed in the

Male 610 324/1 188 503 (51·4%) 607 842/1 183 704 (51·4%) 2482/4799 (51·7%) appendix (p 7).

Maternal age, years

Maternal psychiatric disease was defined by the

12–19 15 929 (1·3%) 15 437 (1·3%) 492 (10·2%)

diagnosis: mental disorders complicating pregnancy,

20–29 541 300 (45·4%) 538 781 (45·4%) 2519 (52·2%)

childbirth, and the puerperium (ICD-10: O99·3B) during

pregnancy or conditions within the ICD-10 chapter

30–39 602 756 (50·6%) 601 118 (50·7%) 1638 (34·0%)

Mental and behavioural disorders (F20-F99) within

40–49 31 275 (2·6%) 31 101 (2·6%) 174 (3·6%)

2 years before delivery to ensure current illness. Maternal

50–61 35 (<0·1%) 35 (<0·1%) 0

chronic somatic disease was defined by a chronic

Ethnicity

condition, as reported by Jølving and colleagues,26 within

Danish 1 169 365 (98·2%) 1 164 603 (98·2%) 4762 (98·7%)

10 years before delivery (appendix p 8). Prenatal exposure

Other 21 930 (1·8%) 21 869 (1·8%) 61 (1·3%)

to substance was defined by hospital contact for

Parity

substance-attributable diagnoses (appendix p 9) given to

Nulliparous 548 039 (46·0%) 545 106 (45·9%) 2933 (60·8%)

the newborn or the mother within 1 year before or during

Parous (1) 444 358 (37·3%) 443 382 (37·4%) 976 (20·2%)

pregnancy. Parity was categorised according to status

Parous (>1) 198 898 (16·7%) 197 984 (16·7%) 914 (19·0%)

before the index birth as 0, 1, and more than 1

Maternal chronic 133 503 (11·2%) 132 582 (11·2%) 921 (19·1%)

(multiparous). Missing data on parity was replaced with

somatic diseases†

counts of recorded before the index birth for each woman

Maternal psychiatric 116 551 (9·8%) 114 147 (9·6%) 2404 (49·8%)

diseases‡ in the Danish Medical Birth Register.14 We used maternal

Substance use§ 5294 (0·4%) 4231 (0·4%) 1063 (22·0%) highest-achieved educational level at delivery as a proxy

ISCED for socioeconomic status and categorised levels into five

Primary and lower 211 445 (17·7%) 208 353 (17·6%) 3092 (64·1%)

groups according to the International Standard

secondary Classification of Education (appendix p 9).27 Births with

Upper secondary 486 393 (40·8%) 485 112 (40·9%) 1281 (26·6%) missing educational information were coded as primary

Short cycle tertiary 357 126 (30·0%) 356 764 (30·1%) 362 (7·5%) and lower secondary. Tobacco use was based on self-

and Bachelor’s degree reported information given at the first antenatal care

or equivalent visit, which was systematically registered from 1999

Master’s degree or 136 331 (11·4%) 136 243 (11·5%) 88 (1·8%) to 2018. Pre-pregnancy BMI was systematically registered

equivalent and

Doctoral degree or from 2004 to 2018. BMI outside the range of 14 to

equivalent 60 kg/m² or less was excluded in order to avoid

Tobacco use¶ 157 185/989 909 (16·0%) 154 627/979 930 (15·8%) 2558/3979 misclassification. All outcomes were examined in births

(64·3%) with available data.

Missing 36 292/989 909 (3·6%) 36 109/979 930 (3·7%) 183/3979 (4·6%)

BMI|| Statistical analysis

Underweight 28 842/702 084 (4·1%) 28 563/699 138 (4·1%) 279/2946 (9·5%) Maternal characteristics for each birth were summarised

(<18·5 kg/m²) using counts and percentages, and differences were

Normal 441 637/702 084 (62·9%) 439 790/699 138 (62·9%) 1847/2946 (62·7%) tested with χ² tests. Logistic regression models with

(18·5–24·9 kg/m²)

robust standard errors were performed to estimate crude

Overweight 149 645/702 084 (21·3%) 149 130/699 138 (21·3%) 515/2946 (17·5%)

(25·0–29·9 kg/m²) and adjusted ORs with 95% CIs for each outcome,

Obese 59 726/702 084 (8·5%) 59 509/699 138 (8·5%) 217/2946 (7·4%) according to heavy prenatal alcohol exposure yes versus

(30·0–34·9 kg/m²) no. Robust standard errors were used to account for

Obese (>34·5 kg/m²) 22 234/702 084 (3·2%) 22 146/699 138 (3·2%) 88/2946 (3·0%) correlations between births by mothers contributing to

Missing 46 293/748 377 (6·2%) 46 038/745 176 (6·2%) 255/3201 (8·0%) study data with more than one birth.28 Outcomes were

Data are n (%) or n/N (%). ISCED=International Standard Classification of Education. BMI=body-mass index.

adjusted for the following potential confounders:

*The distribution of fetal sex excludes stillbirths. †Maternal chronic somatic disease registered within 10 years before maternal age, parity, maternal psychiatric and chronic

birth. ‡Maternal psychiatric disease registered within 2 years before birth. §Maternal substance use registered 1 year somatic diseases, substance use, and highest attained

before or during pregnancy. ¶The distribution of tobacco is only available for 1999–2018. ||The distribution of BMI is

educational level. Outcomes concerning liveborn infants

only available for 2004–18.

were further adjusted for fetal sex. BMI (<18·5,

Table: Baseline characteristics 18·5–24·9, 25·0–29·9, 30·0–34·9, >34·5 kg/m2),

education (primary and lower secondary, upper

complete type. Retained placenta and membranes secondary, short cycle tertiary and Bachelor’s degree or

comprised conditions indicating manual removal, equivalent, or Master’s degree or equivalent and Doctoral

placenta accrete vera without deep invasion of the degree or equivalent), parity (nulliparous, multiparous),

e31 www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023

Articles

and ethnicity (Danish, other) were entered in models as

Abnormalities of forces of labour

categories, and age as a continuous variable. All

Anaemia

confounders were selected before analyses. Sensitivity

Apgar <7/5*†

analyses were done by repeating the aforementioned

Emergency caesarean section

logistic regression model using four modified exposure

Forceps or vacuum delivery

definitions: (1) heavy alcohol exposure restricted in time Gestational diabetes

to only during pregnancy; (2) mothers with a chronic Haemorrhage in early pregnancy

alcohol-attributable condition; (3) mothers with an Haemorrhage in late pregnancy

acute alcohol-attributable diagnosis; (4) restriction to Liver disorders

nulliparous. Maternal characteristics were additionally Perinatal mortality

described. Furthermore, in sensitivity analyses, we added Placenta praevia

the potential confounders tobacco use from 1999 to 2018 Placental abruption

and BMI from 2004 to 2018. All analyses were carried out Planned caesarean section

as complete-case analyses and performed with R software Post-partum haemorrhage >999 mL‡

(version 3.6.1). Post-partum haemorrhage 500−999 mL‡

PPROM

Role of the funding source Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

The funders of the study had no role in study design, Preterm birth*

data collection, data analyses, data interpretation, or Retained placenta and membranes

Small for gestational age* Heavy alcohol exposure

writing of the report.

Stillbirth Yes

No

Results Uterine rupture

Of 1 407 689 Danish singleton births in 1996–2018, 0 5 10 15 20 25 100

Incidence (%)

1 191 295 were deemed eligible after exclusion of women

who had emigrated and loss to follow-up. Of these, Figure 1: Incidences of obstetric and birth outcomes among births with heavy alcohol exposure compared

4823 (0·4%) were identified to have had heavy prenatal with the reference group

alcohol exposure and 1 186 472 were categorised as a Apgar <7/5=Apgar score of less than 7 after 5 min. PPROM=preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes.

*Incidences excluded stillbirths and missing data. †The distribution of Apgar scores were available for 1997–2018.

reference group without identified prenatal heavy alcohol

‡The distribution of post-partum haemorrhage data were available for 2012–18. Further details regarding counts

exposure. Further details of selection of the study and numbers are presented in the appendix (pp 2, 10).

population are shown in the appendix (p 2).

Baseline characteristics of the study population are and tobacco use (71·8%), age older than 39 years (4·9%)

presented in the table. Heavily alcohol-exposed mothers and, together with nulliparous women (appendix pp 14)

were more often younger than 30 (3011 [62·4%] of the highest proportion of underweight (9·4–9·9%).

4823 vs 554 218 [46·7%] of 1 186 472), underweight Mothers with an acute alcohol-attributable diagnosis had

(279 [9·5%] of 2946 vs 28 563 [4·1%] of 699 138), the highest proportion of births during adoles

nulliparous (2933 [60·8%] of 4823 vs 545 106 [45·9%] cence (17·0%), nulliparous births (71·9%), and maternal

of 1 186 472), and more often showed psychiatric chronic somatic diseases (20·6%; appendix p 13).

(2404 [49·8%] of 4823 vs 1 141 147 [9·6%] of 1 186 472) and Incidences of obstetric and birth outcomes are

chronic (921 [19·1%] of 4823 vs 132 582 [11·2%] of 1 186 472) presented in figure 1 and the appendix (p 10). The

somatic diseases, substance (1063 [22·0%] of 4823 vs incidence of perinatal mortality, very and moderate to

4231 [0·4%] of 1 186 472) and tobacco use (2558 [64·3%] of late preterm birth, small for gestational age, and stillbirth

3979 vs 154 627 [15·8%] of 979 930), and a low educational were at least twice as high for alcohol-exposed births as

level (3092 [64·1%] of 4823 vs 208 353 [17·6%] of 1 186 472) for the reference group. The unadjusted and adjusted

compared with the reference group (table 1). We found ORs from the logistic regression analysis are presented

the same characteristics in subgroups of alcohol-exposed in figure 2. Alcohol exposure was significantly associated

mothers (appendix pp 11–14), with the exception of with increased adjusted ORs for small for gestational

mothers with alcohol exposure restricted to during age (OR 2·20 [95% CI 1·97–2·45]), preterm birth

pregnancy (appendix p 11) and a chronic alcohol- (OR 1·32 [1·19–1·46]), haemorrhage in late pregnancy

attributable condition (appendix p 12), who were more (OR 1·25 [1·05–1·49]), and PPROM (OR 1·18

often adolescent mothers, and nulliparous or multiparous [1·00–1·39]). Furthermore, we found significantly

compared with the reference group. Chronic alcohol- decreased adjusted ORs for postpartum haemorrhage

attributable conditions were associated with the highest 500–999 mL (OR 0·80 [95% CI 0·69–0·93]), gestational

proportion of maternal psychiatric diseases (55·9%) diabetes (OR 0·81 [0·67–0·99]), planned caesarean

compared with the other subgroups (appendix section (OR 0·82 [0·72–0·94]), pre-eclampsia and

pp 11, 13–14). Mothers with alcohol exposure restricted to eclampsia (OR 0·83 [0·71–0·96]), and abnormalities of

during pregnancy (appendix p 11) had a low educational forces of labour (OR 0·92 [0·86–0·99]). In the unadjusted

level (67·1%), high amounts of substance use (34·6%) analysis, significantly increased ORs were additionally

www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023 e32

Articles

Unadjusted OR Adjusted OR

abnormalities of forces of labour. Abnormalities of forces

of labour, anaemia, haemorrhage in early and late

Abnormalities of forces of labour 1·03 (0·97–1·10) 0·92 (0·86–0·99) pregnancy, post-partum haemorrhage, caesarean section,

Anaemia 1·22 (1·05–1·42) 1·02 (0·87–1·19)

forceps or vacuum delivery, liver disorders, PPROM, and

Apgar <7/5*† 1·52 (1·16–2·00) 1·00 (0·75–1·33)

uterine rupture are, to our knowledge, novel findings that

Emergency caesarean section 1·17 (1·07–1·29) 0·92 (0·83–1·01)

have not previously been reported.

Forceps or vacuum delivery 0·93 (0·84–1·04) 0·92 (0·82–1·02)

Gestational diabetes 1·13 (0·94–1·37) 0·81 (0·67–0·99)

Maternal heavy alcohol use is associated with

Haemorrhage in early pregnancy 1·31 (1·18–1·46) 1·02 (0·91–1·14) substantial clustering of lifestyle health risks such as

Haemorrhage in late pregnancy 1·81 (1·53–2·14) 1·25 (1·05–1·49) tobacco use and substance use, and psychiatric diseases

Liver disorders 0·92 (0·69–1·24) 0·83 (0·62–1·13) reflecting maternal vulnerability. Whether alcohol leads

Perinatal mortality 1·76 (1·27–2·43) 1·24 (0·88–1·75) to risk behaviour or vice versa is unknown. We found

Placenta praevia 0·79 (0·54–1·17) 0·80 (0·54–1·18) that heavy alcohol exposure was negatively associated

Placental abruption 1·79 (1·39–2·31) 1·27 (0·96–1·66) with gestational diabetes; however, a previously published

Planned caesarean section 0·99 (0·88–1·12) 0·82 (0·72–0·94) meta-analysis (including seven observational studies)

Post-partum haemorrhage >999 mL‡ 0·91 (0·74–1·11) 0·84 (0·68–1·04) concluded no association, nonetheless the included

Post-partum haemorrhage 500−999 mL‡ 0·85 (0·74–0·98) 0·80 (0·69–0·93)

studies found contradictory results and levels of alcohol

PPROM 1·79 (1·53–2·09) 1·18 (1·00–1·39)

consumption unclear.8

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia 1·08 (0·93–1·25) 0·83 (0·71–0·96)

Our findings of increased odds for PPROM and

Preterm birth* 2·16 (1·97–2·37) 1·32 (1·19–1·46)

Retained placenta and membranes 1·19 (0·92–1·54) 1·15 (0·88–1·50)

haemorrhage in late pregnancy were expected, as they

Small for gestational age* 3·64 (3·29–4·01) 2·20 (1·97–2·45)

are precursors of preterm birth. Although our definition

Stillbirth 2·14 (1·43–3·20) 1·44 (0·94–2·20) of preterm birth included both spontaneous preterm

Uterine rupture 0·99 (0·49–1·98) 1·26 (0·62–2·58) labour and induced labour, the increased OR of PPROM

Unadjusted 0 1 2 3 4

and reduced OR of pre-eclampsia and planned caesarean

Adjusted OR (95% CI) section suggest that preterm birth was mainly triggered

by spontaneous preterm labour. The decreased

Figure 2: Association between heavy alcohol exposure and obstetric and birth outcomes

association for planned caesarean section might be

ORs were adjusted for maternal age, parity, maternal chronic somatic and psychiatric disease, substance use, and

educational level. Apgar <7/5=Apgar score of less than 7 after 5 min. OR=odds ratio. PPROM=preterm pre-labour related to the higher incidence of PPROM (3·4% vs 1·9%)

rupture of membranes. *Analyses excluded stillbirths and missing data. †The distribution of Apgar scores were and possibly increased surgical risk factors in heavy-

available for 1997–2018. ‡The distribution of post-partum haemorrhage data were available for 2012–18. Further alcohol-exposed individuals; hence doctors might be less

details are presented in the appendix (p 2).

likely to suggest caesarean section as mode of delivery.

The negative association for post-partum haemorrhages

observed for anaemia, Apgar <7/5, emergency caesarean 500–999 mL was unexpected and might be partly related

section, haemorrhage in early pregnancy, perinatal to the higher incidence of placental abruption

mortality, placental abruption, and stillbirth, but attenu (1·2% vs 0·7%) resulting in immediate treatment, which

ated following adjustment for potential con founders possibly prevents post-partum haemorrhage.

(figure 2). Salihu and colleagues5 assessed the biological

Overall, results from the adjusted main and sensitivity mechanisms of alcohol in placental and fetal development

analyses of women with alcohol exposure restricted to by examining the effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on

during pregnancy, with chronic alcohol use, and the risk of placenta-associated syndromes defined as the

nulliparous women were comparable with the exception occurrence of either placental abruption, placenta

of significantly decreased ORs for abnormalities of forces praevia, pre-eclampsia, small for gestational age, preterm

of labour, and for nulliparous forceps or vacuum delivery birth, or stillbirth. They identified an association for

(appendix p 3). Acute alcohol-attributable diagnosis was placenta-associated syndromes, but no association with

associated with stillbirth, but not small for gestational preeclampsia or placenta praevia in sensitivity analyses.5

age, preterm birth, and PPROM after adjustment We found no association for haemorrhage in early

(appendix p 3). Results of the sensitivity analyses with pregnancy, placenta praevia, placental abruption, post-

tobacco and BMI were comparable with the main partum haemorrhage >999 mL, stillbirth, perinatal

analyses (appendix pp 4–5). mortality, and retained placenta and membranes after

adjustment. The association for pre-eclampsia and

Discussion eclampsia was negative, as shown in sensitivity analyses

This study showed that heavy prenatal alcohol exposure including tobacco and BMI as potential confounders

was associated with small for gestational age, preterm despite slightly attenuated estimates.

birth, haemorrhage in late pregnancy, and PPROM after Contrary to our results, previous studies identified an

adjustment for potential confounders. By contrast, a association between heavy alcohol exposure and

negative association was found for gestational diabetes, stillbirth.5,7 The studies were based on maternal self-

post-partum haemorrhage 500–999 mL, planned reported alcohol consumption and controlled for

caesarean section, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, and potential confounders, but substance use and psychiatric

e33 www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023

Articles

and somatic diseases were not included. However, we which might vary from none to daily heavy alcohol use,

found stillbirth associated with an acute alcohol- potentially underestimating the obstetric and birth

attributable diagnosis. Acute alcohol-attributable versus outcomes on average. However, several births met more

chronic alcohol-attributable diagnoses represent different than one inclusion criterion. Furthermore, 37% of

drinking patterns. However, baseline characteristics were women in alcohol treatment were observed with heavy

generally comparable. We found five outcomes negatively alcohol exposure restricted to during pregnancy, and

associated with alcohol; however, prenatal alcohol additionally 481 (10%) births exclusively met the

consumption is not considered beneficial. exposure inclusion criterion of an alcohol-related

A strength of this study is the nationwide population- diagnosis given to the child, of which 141 (29%) had fetal

based design and large sample size. Furthermore, the alcohol syndrome. Overall, we consider the exposed

Danish tradition of extensive data collection of its cohort to represent pregnancies experiencing the utmost

population allowed adjustment for several potential alcohol-related health con sequences, which might be

confounders. Although a distinction in quantity and type underestimated in this study.

of tobacco use and substance use would be preferable, Despite the health-promoting efforts of the Danish free

such a distinction was not possible. Nonetheless, recall antenatal care programme, our results emphasise a need

bias and co-use of substances seem probable. However, for attention to pre-conceptional health and prenatal

despite the free antenatal care and a general high health alcohol exposure. Our results highlight maternal heavy

status in Danish pregnant women, residual confounding alcohol use as part of a complex lifestyle. Prenatal alcohol

cannot be excluded—heavy alcohol use indicates a exposure remains an urgent public health problem,

maternal vulnerability possibly related to clustering of which seems not to be remedied without a holistic

adversities, which can impact stress and other lifestyle approach targeting detection, prevention, and inter

factors that perhaps affect obstetric and birth outcomes.21 vention towards women in a vulnerable position in life.

Furthermore, some women with heavy alcohol use might In accordance with our knowledge of fetal alcohol

not participate in antenatal care, leading to unrecognised spectrum disorders,4 our results show that prenatal

obstetric complications such as gestational diabetes, pre- alcohol exposure is particularly harmful to fetal health—

eclampsia, anaemia, and light haemorrhage. Anaemia especially small for gestational age and preterm birth,

and light haemorrhage can also be handled by the which are both precursors of infant morbidity and

general practitioner, resulting in a possible under mortality.

estimation of our findings. Moreover, results might be In conclusion, heavy prenatal alcohol exposure is

more pronounced in populations with less health-care associated with adverse obstetric and birth outcomes and

access. Another limitation is the high incidence for some higher proportions of maternal low educational level,

outcomes preventing the interpretation of ORs as relative psychiatric disease, and lifestyle risk behaviors. However,

risks. alcohol consumption is common in many countries.2

The observational unit of births instead of pregnancies Our exposed group represents women and their children

was a limitation. Prenatal alcohol exposure is a risk factor personally experiencing the most adverse alcohol-related

for pregnancy loss and we found a higher incidence of consequences. This highlights a need for attention and a

stillbirths among heavy-alcohol-exposed pregnancies holistic approach towards prenatal alcohol exposure

than in the reference group. Hence, pregnancy loss as starting with pre-conceptional care for everyone.

well as therapeutic terminations represents competing Contributors

risk. Thus, the remaining cohort might represent more MB, CT-P, BMH, USK, KS-L, and TL conceptualised and designed the

robust pregnancies, which potentially can result in analysis; MB and CT-P verified the underlying data and did the data

analysis; MB and JMW created the figures. All authors interpreted the

underestimation of risks attributable to prenatal heavy results. MB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised

alcohol exposure. the work critically for intellectual content and approved the final version

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy has declined of the work to be published; all authors are accountable for all aspects of

substantially in Denmark.29 Our results were generated the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of

any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

based on any hospital contact with 100% alcohol- The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship

attributable diagnosis given to the mother or child and criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

maternal alcohol treatment as an objective proxy measure TL, CT-P, and MB were responsible for project administrative and

with the potential to include individuals that would not material support. USK, CT-P, BMH, and KS-L supervised the study.

MB and CT-P have accessed and verified the underlying data. All authors

self-report heavy alcohol use. Recall bias was avoided. confirm that they had access to the data and accept responsibility for the

However, our estimates did not account for non- decision to submit for publication.

identified alcohol-attributable diseases. Misclassification Declaration of interests

could bias the reference group. Nonetheless, we consider CT-P reports grants for studies from Bayer and Novo Nordisk unrelated

misclassification to have a minor effect on results from to the current study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

the large reference group. Data sharing

A further limitation was lack of information on timing, The nationwide and highly sensitive data used were made available only

within the highly protected environment of the research facilities in the

quantity, frequency, and type of alcohol consumed,

www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023 e34

Articles

state organisation Statistics Denmark. Inquiries about secure access to 13 Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care

data under conditions stipulated by the Danish Data Protection Agency system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to

should be directed to the corresponding author. The authors of this paper database records. Clin Epidemiol 2019; 11: 563–91.

are authorised and willing to discuss such requests with international 14 Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård A, Olsen J, Langhoff-Roos J.

colleagues. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;

33: 27–36.

Acknowledgments 15 Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L,

We would like to thank Jette Meelby, Academic Health Librarian, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of

for valuable information-gathering for our study. This study was supported content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;

by The Obel Family Foundation, The Health Foundation, TrygFonden, 7: 449–90.

Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation, The North Denmark Region 16 The Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee. Classification of surgical

Health Science and Research Foundation, Holms Memorial Foundation, procedures. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/

Dagmar Marshalls Foundation, A.P. Møller og Hustru diva2:970547/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed Sept 28, 2022).

Chastine Mc-Kinney Møllers Foundation, Kong Christian den Tiendes 17 Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sørensen HT,

Fond, Torben and Alice Frimodts Foundation, Tømrermester Axel Kastrup- Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data Resource Profile: the Danish National

Nielsen & Hustru Eva Kastrup-Nielsens Memorial Foundation, Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol 2017; 46: 798–798f.

and Grosserer A.V. Lykfeldts og Hustrus Foundation. 18 Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers.

Scand J Public Health 2011; 39: 91–94.

References

19 Eliasen M, Becker U, Grønbæk M, et al. Alcohol-attributable and

1 Schölin L. Prevention of harm caused by alcohol exposure in

alcohol-preventable mortality in Denmark: an analysis of which

pregnancy: rapid review and case studies from member states. 2016.

intake levels contribute most to alcohol’s harmful and beneficial

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329491 (accessed

effects. Eur J Epidemiol 2014; 29: 15–26.

Sept 28, 2022).

20 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol-related ICD

2 Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J. Estimation of

codes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/ardi/alcohol-related-icd-

national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during

codes.html (accessed Sept 28, 2022).

pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5: e290–99. 21 Skagerstróm J, Chang G, Nilsen P. Predictors of drinking during

pregnancy: a systematic review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;

3 Petersen GL, Kesmodel US, Strandberg-Larsen K. Alkoholforbrug

20: 901–13.

blandt gravide og kvinder i den fertile alder i Danmark. 2015.

https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/ 2015/Alkoholforbrug- 22 O’Leary CM, Halliday J, Bartu A, D’Antoine H, Bower C. Alcohol-

blandt- gravide-og-kvinder-i-den-fertile- alder-i-Danmark_160315. use disorders during and within one year of pregnancy:

ashx?la= da&hash= D1B41F1E20516A1626BF7C49A6DE13 a population-based cohort study 1985–2006. BJOG 2013;

E13AA1B375 (accessed Sept 28, 2022). 120: 744–53.

4 Hoyme HE, Kalberg WO, Elliott AJ, et al. Updated clinical 23 Skalkidou A, Kullinger M, Georgakis MK, Kieler H, Kesmodel US.

guidelines for diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Systematic misclassification of gestational age by ultrasound

Pediatrics 2016; 138: 20154256. biometry: implications for clinical practice and research

methodology in the Nordic countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

5 Salihu HM, Kornosky JL, Lynch O, et al. Impact of prenatal alcohol

2018; 97: 440–44.

consumption on placenta-associated syndromes. Alcohol 2011;

45: 73–79. 24 Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing A, Sultan B.

Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal

6 Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, et al. Dose-response relationship

weights. Acta Paediatr 1996; 85: 8430–38.

between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the

risks of low birthweight, preterm birth and small for gestational age 25 Sundhedsstyrelsen. Vejledning om kriterier for levende-og

(SGA): a systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG 2011; dødfødsel mv. 2005. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2005/~/

118: 1411–21. media/93C011AB599D483B976237969F082523.ashx (accessed

Sept 28, 2022).

7 Bailey BA, Sokol RJ. Prenatal alcohol exposure and miscarriage,

stillbirth, preterm delivery, and sudden infant death syndrome. 26 Jølving LR, Nielsen J, Kesmodel US, Nielsen RG, Beck-Nielsen SS,

Alcohol Res Health 2011; 34: 86–91. Nørgård BM. Prevalence of maternal chronic diseases during

pregnancy—a nationwide population based study from 1989 to

8 Hu SL, He BT, Zhang, RJ. Association between maternal alcohol

2013. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016; 95: 1295–304.

use during pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus:

a meta-analysis. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries 2021; 41: 189–95. 27 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011.

9 Steane SE, Young SL, Clifton VL et al. Prenatal alcohol consumption

2012. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/

and placental outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of

international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf.

clinical studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021; 225: 607.e1–22.

(accessed Sept 28, 2022).

10 May PA, Gossage JP. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol

28 Huber P J. “The Behavior of Maximum Likelihood Estimates under

spectrum disorders: not as simple as it might seem.

Nonstandard Conditions”, proceedings of the fifth Berkeley

Alcohol Res Health 2011; 34: 15–26.

symposium on mathematical statistics and probability 1967;

11 Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Brønnum-Hansen H. 5.1: 221–33.

Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social

29 Strandberg-Larsen K, Andersen AN, Kesmodel US. Unreliable

issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving.

estimation of prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome.

Scand J Public Health 2011; 39: 12–16.

Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5: e6.

12 Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil

Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;

29: 541–49.

e35 www.thelancet.com/public-health Vol 8 January 2023

You might also like

- Maternal Prepregnancy BMI and Risk of Cerebral Palsy in OffspringDocument11 pagesMaternal Prepregnancy BMI and Risk of Cerebral Palsy in Offspringnurul habibaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Outcomes in Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Epidemiology and PreventionDocument10 pagesPregnancy Outcomes in Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Epidemiology and PreventionsenkonenNo ratings yet

- Congenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European JournaDocument1 pageCongenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European Journaburak yolcuNo ratings yet

- Drug Therapy During PregnancyFrom EverandDrug Therapy During PregnancyTom K. A. B. EskesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Risk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyDocument9 pagesRisk Factor For Sever Postpartum Hemorrhage A Case Control StudyAhmad SyaukatNo ratings yet

- Frederiksen 2018Document7 pagesFrederiksen 2018WinniaTanelyNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Gestational Risk Factors For HypospadiasDocument6 pagesMaternal and Gestational Risk Factors For Hypospadiaspldhy2004No ratings yet

- Health of Children Born To Mothers Who Had Preeclampsia: A Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesHealth of Children Born To Mothers Who Had Preeclampsia: A Population-Based Cohort StudyAdhitya Pratama SutisnaNo ratings yet

- 33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831Document6 pages33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831AnggaNo ratings yet

- Cancer in Frozen Embryo TransferDocument21 pagesCancer in Frozen Embryo Transferadnoctum18No ratings yet

- Previous Abortions and Risk of Pre-Eclampsia: Reproductive HealthDocument8 pagesPrevious Abortions and Risk of Pre-Eclampsia: Reproductive HealthelvanNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument7 pagesContent ServerJelena VidićNo ratings yet

- Maternal Smoking - NEC MortalityDocument7 pagesMaternal Smoking - NEC MortalityGlen LazarusNo ratings yet

- Alcohol, Drugs and Medication in Pregnancy: The Long Term Outcome for the ChildFrom EverandAlcohol, Drugs and Medication in Pregnancy: The Long Term Outcome for the ChildPhilip M PreeceRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- ECPM2016 ABSTRACTBOOKTheJournalofMaternal-FetalNeonatalMedicine PDFDocument314 pagesECPM2016 ABSTRACTBOOKTheJournalofMaternal-FetalNeonatalMedicine PDFDiana-Elena ComandasuNo ratings yet

- Herrera 2017Document9 pagesHerrera 2017Bianca Maria PricopNo ratings yet

- 5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFDocument15 pages5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFputri vinia /ilove cuteNo ratings yet

- Maternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesMaternal Underweight and The Risk of Spontaneous Abortion: Original ArticleKristine Joy DivinoNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Voerman - Ped Obesity - Associations of Maternal & Infant Metabolite Profiles With Fetal Growth & Odds Adverse OutcomesDocument11 pages2021 - Voerman - Ped Obesity - Associations of Maternal & Infant Metabolite Profiles With Fetal Growth & Odds Adverse OutcomespaletaNo ratings yet

- Original Research Paper Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument4 pagesOriginal Research Paper Obstetrics & GynaecologyVogireddy SindhuNo ratings yet

- Congenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandCongenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementDiva D. De León-CrutchlowNo ratings yet

- Maternal Risk Factors Associated With The Development of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate in Mexico: A Case-Control StudyDocument7 pagesMaternal Risk Factors Associated With The Development of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate in Mexico: A Case-Control StudyFauzi NoviaNo ratings yet

- Lafalla 2019Document26 pagesLafalla 2019Chicinaș AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Imaging of Gynecological Disorders in Infants and ChildrenFrom EverandImaging of Gynecological Disorders in Infants and ChildrenGurdeep S. MannNo ratings yet

- Association Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyPujiyono SuwadiNo ratings yet

- Predictive Factors For Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women: A Unvariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression AnalysisDocument5 pagesPredictive Factors For Preeclampsia in Pregnant Women: A Unvariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression AnalysisTiti Afrida SariNo ratings yet

- Method of Hormonal Contraception and Protective.8Document7 pagesMethod of Hormonal Contraception and Protective.8Christian VieryNo ratings yet

- Por Qué Los Bebés Mueren en Nacimientos Fuera de Los Hospitales-Muerte PerinatalDocument8 pagesPor Qué Los Bebés Mueren en Nacimientos Fuera de Los Hospitales-Muerte PerinatalDiana Berenice Colin PompaNo ratings yet

- Original Contribution Coffee and Fetal Death: A Cohort Study With Prospective DataDocument8 pagesOriginal Contribution Coffee and Fetal Death: A Cohort Study With Prospective DataverokendekNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Acute Respiratory Morbidity in Moderately Preterm InfantsDocument10 pagesRisk Factors For Acute Respiratory Morbidity in Moderately Preterm InfantsYeda NicolNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AsliDocument22 pagesJurnal Aslijulian mukaromNo ratings yet

- Vol9 Issue1 06Document4 pagesVol9 Issue1 06annisaNo ratings yet

- General Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SADocument1 pageGeneral Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SAElva Diany SyamsudinNo ratings yet

- BMJ f6398Document13 pagesBMJ f6398Luis Gerardo Pérez CastroNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Threatened Abortions On Pregnancy OutcomesDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Threatened Abortions On Pregnancy OutcomesfrankyNo ratings yet

- Manejo Cancer in Pregnancy Fetal and Neonatal OutcomesDocument17 pagesManejo Cancer in Pregnancy Fetal and Neonatal OutcomesLaura LealNo ratings yet

- Ursodeoxycholic Acid Versus Placebo in Women With Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (PITCHES) - A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesUrsodeoxycholic Acid Versus Placebo in Women With Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (PITCHES) - A Randomised Controlled TrialcohortehospitalevitaNo ratings yet

- Aogs 12933Document11 pagesAogs 12933Warawiri 11No ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading ObygnDocument6 pagesJurnal Reading ObygnLimastani FebrianaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Parity On Risk of Complications in Women With Epilepsy: A Population Based Cohort StudyDocument22 pagesThe Effect of Parity On Risk of Complications in Women With Epilepsy: A Population Based Cohort StudyRivani HasanNo ratings yet

- Maternal Drug Use and Infant Cleft Lip/Palate With Special Reference To CorticoidsDocument5 pagesMaternal Drug Use and Infant Cleft Lip/Palate With Special Reference To CorticoidsGusnia Ira Hastuti HutabaratNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0920996420301584 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0920996420301584 MainAndreaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandDiabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementNo ratings yet

- 070Document8 pages070Ella ChiraNo ratings yet

- Maternal Hypothyroidism During Pregnancy and The Risk of Pediatric Endocrine Morbidity in The OffspringDocument6 pagesMaternal Hypothyroidism During Pregnancy and The Risk of Pediatric Endocrine Morbidity in The OffspringlananhslssNo ratings yet

- The Placenta and Neurodisability 2nd EditionFrom EverandThe Placenta and Neurodisability 2nd EditionIan CrockerNo ratings yet

- Hargreave2018 JurnalDocument8 pagesHargreave2018 JurnalAgung Budi PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Quality of Life of Children With Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesQuality of Life of Children With Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic ReviewNila Sari ChandraNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 1: EENT (Eyes, Ears, Nose and Throat)From EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 1: EENT (Eyes, Ears, Nose and Throat)No ratings yet

- Poryo2018 IvhDocument8 pagesPoryo2018 IvhGabriel DaneaNo ratings yet

- thay đổi tỉ lệ phát hiện tim (di tật lớn ở tim) 2019Document27 pagesthay đổi tỉ lệ phát hiện tim (di tật lớn ở tim) 2019Ngô HùngNo ratings yet

- Care in Pregnancies Subsequent To Stillbirthor Perinatal DeatDocument12 pagesCare in Pregnancies Subsequent To Stillbirthor Perinatal DeatgalalNo ratings yet

- 1471-0528 16283Document8 pages1471-0528 16283saeed hasan saeedNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument6 pagesDownloadKai GgNo ratings yet

- Medical Record Validation of Maternally Reported History of PreeclampsiDocument7 pagesMedical Record Validation of Maternally Reported History of PreeclampsiezaNo ratings yet

- Epilepsi Pada Ibu HamilDocument9 pagesEpilepsi Pada Ibu Hamilverinda S 99No ratings yet

- V 17 N 3 Ao 3Document7 pagesV 17 N 3 Ao 3Rosmery Martinez HinojosaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 5Document6 pagesArticulo 5Monica ReyesNo ratings yet

- Being Macrosomic at Birth Is An Independent Predictor of Overweight in Children: Results From The IDEFICS StudyDocument9 pagesBeing Macrosomic at Birth Is An Independent Predictor of Overweight in Children: Results From The IDEFICS StudySayuri BenitesNo ratings yet

- RH IncompatibilityDocument9 pagesRH IncompatibilitySerafin Dimalaluan III50% (2)

- JAN 10, 2015 Opd CensusDocument3 pagesJAN 10, 2015 Opd CensusRachelleFuentespinaNo ratings yet

- First Trimester Bleeding ReportDocument35 pagesFirst Trimester Bleeding ReportAnita PrietoNo ratings yet

- Teenage Pregnancy in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesTeenage Pregnancy in The PhilippinesJanine Marie CaprichosaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Efficacy and Complications of IUD Insertion in Immediate Postplacental/early Postpartum Period With Interval Period: 1 Year Follow-UpDocument6 pagesComparison of Efficacy and Complications of IUD Insertion in Immediate Postplacental/early Postpartum Period With Interval Period: 1 Year Follow-UpJum Natosba BaydNo ratings yet

- Laporan Mingguan Unit Gawat Darurat Kamar Bersalin 1. Jumlah KasusDocument7 pagesLaporan Mingguan Unit Gawat Darurat Kamar Bersalin 1. Jumlah Kasuszayed norwantoNo ratings yet

- Gestational Trophoblastic Diseases Hydatiform MoleDocument40 pagesGestational Trophoblastic Diseases Hydatiform MoleL3SNo ratings yet

- Obstetric History Template 21Document3 pagesObstetric History Template 21Raniya AhmedNo ratings yet

- 3 - ICM 2 - PPH - NotesDocument6 pages3 - ICM 2 - PPH - NotesthaniaNo ratings yet

- UltrasoundDocument1 pageUltrasoundMalote Elimanco Alaba100% (1)

- Jadwal Kegiatan Blok-18 Sistem ReproduksiDocument7 pagesJadwal Kegiatan Blok-18 Sistem Reproduksiicha chanNo ratings yet

- Hursthouse AbortionDocument10 pagesHursthouse Abortionchadi81No ratings yet

- Prevention of RH AlloimmunizationDocument9 pagesPrevention of RH AlloimmunizationanembrionadoNo ratings yet

- Preterm Labor Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesPreterm Labor Case AnalysisJOPAR JOSE C. RAMOSNo ratings yet

- Delivery of TwinsDocument14 pagesDelivery of TwinsMeliana JayasaputraNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Three Methods of Fetal Weight Estimation During The Active Stage of Labor Performed by Residents: A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesComparison Between Three Methods of Fetal Weight Estimation During The Active Stage of Labor Performed by Residents: A Prospective Cohort StudyMahida El shafiNo ratings yet

- Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM) : Why Focus On PPROM?Document4 pagesPreterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM) : Why Focus On PPROM?sasoyNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 pageDaftar PustakaDwi sarwindahNo ratings yet

- Abortion TypesDocument19 pagesAbortion TypesFany MaldoNo ratings yet

- Placenta Accreta Spectrum and Postpartum Hemorrhag - 230510 - 170158Document10 pagesPlacenta Accreta Spectrum and Postpartum Hemorrhag - 230510 - 170158Nilfacio PradoNo ratings yet

- Cif Zika - 2016 PDFDocument3 pagesCif Zika - 2016 PDFNicholai CabadduNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Pregnant Woman 2023Document2 pagesAssessment of Pregnant Woman 2023ysohidalgo13No ratings yet

- Shoulder PresentationDocument8 pagesShoulder PresentationvincentsharonNo ratings yet

- What Is A Maternity NurseDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Maternity NurseRiani ListiNo ratings yet

- 2022 AJOG A Laparoscopic Approach To Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyDocument3 pages2022 AJOG A Laparoscopic Approach To Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyWilliam AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Case SheetDocument4 pagesAntenatal Case SheetRichard SnellNo ratings yet

- Postpartum HemorrhageDocument30 pagesPostpartum HemorrhageMusekhirNo ratings yet

- Midwife Led Care BelgiumDocument19 pagesMidwife Led Care BelgiumsinarNo ratings yet

- Unit 17Document21 pagesUnit 17Bhaiya KamalenduNo ratings yet

- Coass in Charge: Fara/Vicia/Yanti/ Eva/Tryas/Desi Supervisor: Dr. Mulyo Hadi Sungkono, SP - OG (K)Document15 pagesCoass in Charge: Fara/Vicia/Yanti/ Eva/Tryas/Desi Supervisor: Dr. Mulyo Hadi Sungkono, SP - OG (K)Tryas YulithaNo ratings yet