Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rizal Module 10

Uploaded by

priagolavinchent0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesLesson Material on Rizal's Life

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLesson Material on Rizal's Life

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesRizal Module 10

Uploaded by

priagolavinchentLesson Material on Rizal's Life

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

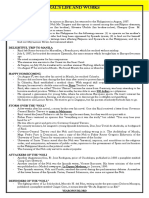

CHAPTER 10

First Homecoming, 1887-88

Chapter Summary:

Decision to return Home. Because of the publication of the Noli Me Tangere and the uproar it

caused among the friars, Rizal was warned by Paciano (his brother), Silvestre Ubaldo (his

brother-in-law), Chengoy (Jose M. Cecilio), and other friends not to return home. But he did not

heed their warning. He was determined to return to the Philippines for the following reasons: (1)

to operate on his mother eyes; (2) to serve his people who had long been oppressed by Spanish

tyrants; (3) to find out for himself how the Noli and his other writings were affecting Filipinos

and Spaniards in the Philippines; and (4) to inquire why Leonor Rivera remained silent.

In Rome, on June 29, 1887, Rizal wrote to his father, announcing his homecoming. “On

the 15 of July, at the latest”, he wrote, “I shall embark for our country, so that from the 15 th to

th

the 30th of August, we shall see each other”.

Delightful Trip to Manila. Rizal left Rome by train for Marseilles, a French port, which he

reached without mishap. On July 13, 1887, he boarded the steamer Djemnah, the same steamer

which brought him to Europe five years ago. There were about 50 passengers, including 4

Englishmen, 2 Germans, 3 Chinese, 2 Japanese, many Frenchmen, and 1 Filipino (Rizal).

At Saigon, on July 30, he transferred to another steamer Haiphong which was Manila-

bound. On August 2, this steamer left Saigon for Manila.

Arrival in Manila. Rizal’s voyage from Saigon to Manila was pleasant. On August 3 rd the moon

was full, and he slept soundly the whole night. The calm sea, illuminated by the silvery

moonlight, was a magnificent sight to him.

Happy Homecoming. On August 8th, he returned to Calamba. His family welcomed him

affectionately, with plentiful tears of joy. Writing to Blumentritt of his homecoming, he said: “I

had a pleasant voyage. I found my family enjoying good health and our happiness was great in

seeing each other again. They shed tears of joy and I had to answer ten thousand questions at the

same time”.

Rizal suffered one failure during his six months of sojourn in Calamba – his failure to see

Leonor Rivera. He tried to go to Dagupan, but his parents absolutely forbade him to go because

Leonor’s mother did not like him for a son-in-law. With a heavy heart, Rizal bowed to his

parent’s wish. He was caught within the iron grip of the custom of his time that marriages must

be arranged by the parents of both groom and bride.

Attackers of the Noli. The battle over the Noli took the form of a virulent war of words. Father

Font printed his report and distributed copies of it in order to discredit the controversial novel.

Another Augustinian, Fr. Jose Rodriguez, Prior of Guadalupe, published a series of eight

pamphlets under the general heading Cuestioners de Sumo Interes (Questions of supreme

Interest) to blast the Noli and other anti-Spanish writings. These eight pamphlets were entitled as

follows:

1. Porque no los he de leer? (Why Should I not Read Them?)

2. Guardaos de ellos. Porque? (Beware of Them. Why?)

3. Y_que me dice usted de la peste? (And What Can You Tell Me of Plague?)

4. Porque triunfan los impos? (Why Do the Impious Triump?)

5. Cree usted que de versa no hay purgatorio? (Do You Think There Is Really No

Purgatory?)

6. Hay o no hay infierno? (Is There or Is There No Hell?)

7. Que le parece a usted de esos libelos? (What Do You Think of These Libels?)

8. Confesion o condenacion? (Confession or Damnation?)

Repercussions of the storm over the Noli reached Spain. It was fiercely attacked on the session

hall of the senate of the Spanish Cortes by various senators, particularly General Jose de

Salamanca on April 1, 1888, General Luis M. de Pando April 12, and Sr. Fernando Vida on June

11. The Spanish academician of Madrid, Vicente Barrantes, who formerly occupied high

government positions in the Philippines, bitterly criticized the Noli in an article published in La

España Moderna (A newspaper of Madrid) in January, 1890.

Defenders of the Noli. The much-maligned Noli had its gallant defenders who fearlessly came

out to prove the merits of the novel or to refute the arguments of the unkind attackers. Marcelo

H. del Pilar, Dr. Antonio Ma. Regidor, Graciano Lopez Jaena, Mariano Ponce, and other Filipino

reformist in foreign lands, of course, rushed to uphold the truths of the Noli. Father Sanchez,

Rizal’s favorite teacher at the Ateneo, defended and praised it in public. Don Segismundo Moret,

former Minister of the Crown; Dr. Miguel Morayta, historian and statesman; and Professor

Blumentritt, scholar and educator, read and liked the novel.

A brilliant defense of the Noli came from an unexpected source. It was by Rev. Vicente

Garcia, a Filipino Catholic priest-scholar, a theologian of the Manila Cathedral, and a Tagalog

translator of the famous Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis. Father Garcia, writing under

the penname Justo Desiderio Magalang, wrote a defense of the Noli which was published in

Singapore as an appendix to a pamphlet dated July 18, 1888. He blasted the arguments of Fr.

Rodriguez.

Rizal and Taviel de Andrade. While the storm over the Noli was raging in fury, Rizal was not

molested in Calamba. This is due to Governor General Terrero’s generosity in assigning a

bodyguard to him. Between this Spanish bodyguard, Lt. Jose Taviel de Andrade, and Rizal a

beautiful friendship bloomed.

What marred Rizal’s happy days in Calamba with Lt. Andrade were (1) the death of his

older sister, Olimpia, and (2) the groundless tales circulated by his enemies that he was “a

German spy, an agent of Bismarck, a Protestant, a Mason, a witch, a soul beyond salvation, etc.”

Calamba’s Agrarian Trouble. Governor General Terrero, influenced by certain facts in Noli

Me Tangere, ordered a government investigation of the friars estates to remedy whatever

iniquities might have been present in connection with lands taxes and with tenant relations. One

of the friar estates affected was the Calamba Hacienda which Dominican Order Owned since

1883. In compliance with the governor general’s orders, dated December 30, 1887, the Civil

Governor of Laguna Province directed the municipal authorities of Calamba to investigate the

agrarian conditions of their locality.

Farewell to Calamba. Rizal’s exposure of the deplorable conditions of tenancy in

Calamba infuriated his enemies. The friars exerted pressure on Malacañan Palace to eliminate

him. They asked Governor General Terrero to deport him, but the latter refused because there

was no valid charge against Rizal in court. Anonymous threats against Rizal’s life were received

by his parents. The alarmed parents, relatives and friends (including Lt. Jose Taviel de Andrade)

advised him go away, for his life was in danger.

This time Rizal had to go. He could not very well disobey the Governor General’s veiled

orders. But he was not running like a coward from a fight. He was courageous, a fact which his

worst enemies could not deny. A valiant hero that he was, he was not afraid of any man and

neither was he afraid to die. He was compelled to leave Calamba for two reasons: (1) his

presence in Calamba was jeopardizing the safety and happiness of his family and friends and (2)

he could fight better his enemies and serve his country’s cause with greater efficacy by writing in

foreign counties.

A Poem for Lipa. Shortly before Rizal left Calamba inn 1888 his friend from Lipa requested

him to write a poem in commemoration of the town’s elevation to a villa (city) by virtue of the

Becerra Law of 1888. Gladly, he wrote a poem dedicated to the industrious folks of Lipa. This

was the “Himno al Trabajo” (Hymn to Labor). He finished it and sent it to Lipa before his

departure from Calamba.

Chapter Test

Direction: Make a collage on how Rizal made his first homecoming in 1887-88. 20 points

You might also like

- Nakatutuwa Ka Talaga, RizalDocument29 pagesNakatutuwa Ka Talaga, RizalJhon Kyle RoblesNo ratings yet

- First Homecoming 2Document27 pagesFirst Homecoming 2Madali Ghyrex ElbanbuenaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10-2Document29 pagesChapter 10-2Salnor Mohammad TomantoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document3 pagesChapter 10Anonymous cZQ3Ich9S3No ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document16 pagesChapter 11Jayhan PalmonesNo ratings yet

- Report Rizal Chapter10Document1 pageReport Rizal Chapter10Eej-la Yasuham Airolev83% (6)

- Chapter11 RizalDocument30 pagesChapter11 RizalVirgilio Bernardino IINo ratings yet

- Danes T.Document3 pagesDanes T.Ryan AntonioNo ratings yet

- Transcript of Chapter 10: Rizal's First Homecoming, 1887-88Document3 pagesTranscript of Chapter 10: Rizal's First Homecoming, 1887-88Orlando Jr GalvezNo ratings yet

- RizalDocument36 pagesRizalMylene Sunga AbergasNo ratings yet

- Rizal 10 - 15Document23 pagesRizal 10 - 15Yhan Brotamonte BoneoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10: Rizal's First Homecoming, 1887-88Document3 pagesChapter 10: Rizal's First Homecoming, 1887-88jayson espinasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 & 11Document41 pagesChapter 10 & 11TyrelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - First HomecomingDocument6 pagesChapter 10 - First HomecomingGerald Tan EullaranNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Back To CalambaDocument5 pagesChapter 11 Back To CalambaPEK CEFNo ratings yet

- 8 Rizals First Homecoming in CalambaDocument13 pages8 Rizals First Homecoming in CalambaENRIQUEZ, JETHRO C.No ratings yet

- RizalindaDocument30 pagesRizalindaMylene Sunga AbergasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 First HomecomingDocument25 pagesChapter 10 First HomecomingprincejaeirielsisonNo ratings yet

- Rizal Chapter 10Document12 pagesRizal Chapter 10Harvey Pineda80% (5)

- LESSON 5 - First HomecomingDocument6 pagesLESSON 5 - First HomecomingAiron BendañaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document14 pagesChapter 11Mabeth TabernillaNo ratings yet

- Felipe, Rudolph C. - Summary Chapter 10 - 12Document8 pagesFelipe, Rudolph C. - Summary Chapter 10 - 12Rudolph FelipeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 RizalDocument21 pagesChapter 10 RizalClaribel LamsisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - RizalDocument23 pagesChapter 10 - RizalMark Angelo S. Enriquez86% (36)

- (RIZAL 101) First HomecomingDocument6 pages(RIZAL 101) First HomecomingMae PandoraNo ratings yet

- DrizalDocument4 pagesDrizalNam JuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 RizalDocument23 pagesChapter 10 RizalJoyce Nato100% (1)

- Chapter 10 RizalDocument24 pagesChapter 10 RizalLiam MeerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document2 pagesChapter 9Prince MendozaNo ratings yet

- Friars and Filipinos / An Abridged Translation of Dr. Jose Rizal's Tagalog Novel, / 'Noli Me Tangere.'From EverandFriars and Filipinos / An Abridged Translation of Dr. Jose Rizal's Tagalog Novel, / 'Noli Me Tangere.'No ratings yet

- Back To CalambaDocument8 pagesBack To CalambaBernard CastilloNo ratings yet

- RIzal - Chapter 11Document4 pagesRIzal - Chapter 11eathan27100% (13)

- An Eagle Flight: A Filipino Novel Adapted from Noli Me TangereFrom EverandAn Eagle Flight: A Filipino Novel Adapted from Noli Me TangereRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Lesson 5 Part 2 of His LifeDocument5 pagesLesson 5 Part 2 of His LifesofiaNo ratings yet

- Rizal'S First Homecoming (1887-1888)Document34 pagesRizal'S First Homecoming (1887-1888)Kelly Jane ChuaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13: The Trouble of Noli Me Tangere: TH THDocument4 pagesLesson 13: The Trouble of Noli Me Tangere: TH THErika ApitaNo ratings yet

- Chapter10 Home Coming RealDocument7 pagesChapter10 Home Coming RealKathleen A. PascualNo ratings yet

- First HomecomingDocument50 pagesFirst HomecomingNicole Mallari Mariano100% (2)

- The First Homecoming 5Document26 pagesThe First Homecoming 5Rosda DhangNo ratings yet

- Group 3-Rizal Social OriginsDocument4 pagesGroup 3-Rizal Social OriginsEster Thea GerundaNo ratings yet

- Local Media8453414589275423798Document15 pagesLocal Media8453414589275423798Franchesca Ashley Marie BasilioNo ratings yet

- Gem 101-Lesson 5-6Document14 pagesGem 101-Lesson 5-6Jocyn Marie RubiteNo ratings yet

- RizalDocument34 pagesRizalLilia A JaimeNo ratings yet

- Rizal ManualDocument49 pagesRizal ManualDalen BayogbogNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Life of Jose RizalDocument24 pagesChapter 10 Life of Jose RizalCamille Arocena DoradoNo ratings yet

- Group 10 Rizal in LondonDocument10 pagesGroup 10 Rizal in LondonJared PaulateNo ratings yet

- Group 12 RizalDocument53 pagesGroup 12 RizalRoel SampeloNo ratings yet

- Jose Rizal Final Week1Document3 pagesJose Rizal Final Week1Kevin MagdayNo ratings yet

- Rizal Life and Works Chapter Summary 9-13Document8 pagesRizal Life and Works Chapter Summary 9-13Luigi De Real89% (19)

- Life and Works of Rizal in London 1888-1889Document40 pagesLife and Works of Rizal in London 1888-1889Jerrica PerianoNo ratings yet

- Rizal-Chapter 14Document6 pagesRizal-Chapter 14anon_611253013No ratings yet

- Rizal's Return in The PhilippinesDocument31 pagesRizal's Return in The PhilippinesJohanna Gutierrez100% (1)

- Rizal T 8Document5 pagesRizal T 8RESI-AURIN, JK L.No ratings yet

- Report Chapter 11-15Document87 pagesReport Chapter 11-15Neil bryan Moninio100% (2)

- 7 Noli Me Tangere 2022Document17 pages7 Noli Me Tangere 2022jwn dumpNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document25 pagesChapter 10Miriam TabiosNo ratings yet

- The History of Louisiana, Or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina Containing a Description of the Countries That Lie on Both Sides of the River MissisippiFrom EverandThe History of Louisiana, Or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina Containing a Description of the Countries That Lie on Both Sides of the River MissisippiNo ratings yet

- Delphi Complete Works of George Washington Cable IllustratedFrom EverandDelphi Complete Works of George Washington Cable IllustratedNo ratings yet

- NSTP 122 MidtermDocument2 pagesNSTP 122 MidtermpriagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- Power Engineering SummaryDocument9 pagesPower Engineering SummarypriagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- NSTP 122 MidtermDocument2 pagesNSTP 122 MidtermpriagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- Art App Final TermDocument3 pagesArt App Final TermpriagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- Rizal - Module 9Document2 pagesRizal - Module 9priagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- Rizal - Module 6Document4 pagesRizal - Module 6priagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- Rizal - Module 1Document5 pagesRizal - Module 1priagolavinchentNo ratings yet

- A N S W e R-Accion PublicianaDocument9 pagesA N S W e R-Accion PublicianaEdward Rey EbaoNo ratings yet

- Tales From The Wood RPGDocument51 pagesTales From The Wood RPGArthur Taylor100% (1)

- 19 March 2018 CcmaDocument4 pages19 March 2018 Ccmabronnaf80No ratings yet

- Odisha State Museum-1Document26 pagesOdisha State Museum-1ajitkpatnaikNo ratings yet

- Nift B.ftech Gat PaperDocument7 pagesNift B.ftech Gat PapergoelNo ratings yet

- Construction Quality Management 47 PDFDocument47 pagesConstruction Quality Management 47 PDFCarl WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Effective Leadership Case Study AssignmentDocument5 pagesEffective Leadership Case Study AssignmentAboubakr Soultan67% (3)

- Streetcar - A Modern TradegyDocument4 pagesStreetcar - A Modern Tradegyel spasser100% (2)

- 13 19 PBDocument183 pages13 19 PBmaxim reinerNo ratings yet

- Kashida Embroidery: KashmirDocument22 pagesKashida Embroidery: KashmirRohit kumarNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: Modern Biotechnological Processes: Guidelines For Choosing Host-Vector SystemsDocument3 pagesUnit 4: Modern Biotechnological Processes: Guidelines For Choosing Host-Vector SystemsSudarsan CrazyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document35 pagesChapter 9Cameron LeishmanNo ratings yet

- AP Macroeconomics: About The Advanced Placement Program (AP)Document2 pagesAP Macroeconomics: About The Advanced Placement Program (AP)Adam NowickiNo ratings yet

- Contoh Writing AdfelpsDocument1 pageContoh Writing Adfelpsmikael sunarwan100% (2)

- 1.introduction To Narratology. Topic 1 ColipcaDocument21 pages1.introduction To Narratology. Topic 1 ColipcaAnishoara CaldareNo ratings yet

- Systematic Survey On Smart Home Safety and Security Systems Using The Arduino PlatformDocument24 pagesSystematic Survey On Smart Home Safety and Security Systems Using The Arduino PlatformGeri MaeNo ratings yet

- Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing PDFDocument807 pagesAdvances in Intelligent Systems and Computing PDFli250250250No ratings yet

- MailEnable Standard GuideDocument53 pagesMailEnable Standard GuideHands OffNo ratings yet

- Sword Art Online - Unital Ring IV, Vol. 25Document178 pagesSword Art Online - Unital Ring IV, Vol. 257022211485aNo ratings yet

- "The Sacrament of Confirmation": The Liturgical Institute S Hillenbrand Distinguished LectureDocument19 pages"The Sacrament of Confirmation": The Liturgical Institute S Hillenbrand Distinguished LectureVenitoNo ratings yet

- 17.5 Return On Investment and Compensation ModelsDocument20 pages17.5 Return On Investment and Compensation ModelsjamieNo ratings yet

- Hemzo M. Marketing Luxury Services. Concepts, Strategy and Practice 2023Document219 pagesHemzo M. Marketing Luxury Services. Concepts, Strategy and Practice 2023ichigosonix66No ratings yet

- Naija Docs Magazine Issue 6Document46 pagesNaija Docs Magazine Issue 6Olumide ElebuteNo ratings yet

- Spiderman EvolutionDocument14 pagesSpiderman EvolutionLuis IvanNo ratings yet

- Graph Theory and ApplicationsDocument45 pagesGraph Theory and Applicationssubramanyam62No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Culture - Chapter 13Document11 pagesEntrepreneurial Culture - Chapter 13bnp guptaNo ratings yet

- A REPORT ON MIMO IN WIRELESS APPLICATIONS - FinalDocument11 pagesA REPORT ON MIMO IN WIRELESS APPLICATIONS - FinalBha RathNo ratings yet

- Clinical Standards For Heart Disease 2010Document59 pagesClinical Standards For Heart Disease 2010Novita Dwi MardiningtyasNo ratings yet

- Synonyms & Antonyms of Mop: Save Word To Save This Word, You'll Need To Log inDocument6 pagesSynonyms & Antonyms of Mop: Save Word To Save This Word, You'll Need To Log inDexterNo ratings yet

- HRA Strategic PlanDocument40 pagesHRA Strategic PlanjughomNo ratings yet