Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effectsof Early Neglectonlanguageandcognition

Uploaded by

FARHAT HAJEROriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effectsof Early Neglectonlanguageandcognition

Uploaded by

FARHAT HAJERCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/236913014

The Effects of Early Neglect on Cognitive, Language, and Behavioral

Functioning in Childhood

Article in Psychology · February 2012

DOI: 10.4236/psych.2012.32026 · Source: PubMed

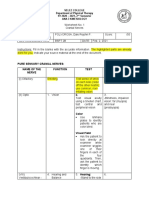

CITATIONS READS

130 4,645

10 authors, including:

Eve G Spratt Samantha Pittenger

University of Vermont Medical Center Yale University

49 PUBLICATIONS 2,151 CITATIONS 20 PUBLICATIONS 403 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Cynthia Cupit Swenson Michael de Bellis

Medical University of South Carolina Duke University

54 PUBLICATIONS 1,400 CITATIONS 127 PUBLICATIONS 15,926 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Eve G Spratt on 10 March 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Psychology

2012. Vol.3, No.2, 175-182

Published Online February 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.32026

The Effects of Early Neglect on Cognitive, Language, and

Behavioral Functioning in Childhood

Eve G. Spratt1,2*, Samantha Friedenberg2, Angela LaRosa1, Michael D. De Bellis3,

Michelle M. Macias1, Andrea P. Summer1, Thomas C. Hulsey1,

Des K. Runyan4, Kathleen T. Brady2

1

Department of Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, USA

2

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, USA

3

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University, Durham, USA

4

Department of Pediatrics, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, USA

Email: *spratte@musc.edu

Received October 5th, 2011; revised November 21st, 2011; accepted December 24th, 2011

Objectives: Few studies have explored the impact of different types of neglect on children’s development.

Measures of cognition, language, behavior, and parenting stress were used to explore differences between

children experiencing various forms of neglect, as well as to compare children with and without a history

of early neglect. Methods: Children, ages 3 to 10 years with a history of familial neglect (USN), were

compared to children with a history of institutional rearing (IA) and children without a history of neglect

using the Differential Abilities Scale, Test of Early Language Development, Child Behavior Checklist,

and Parenting Stress Index. Factors predicting child functioning were also explored. Results: Compared

with youth that were not neglected, children with a history of USN and IA demonstrated lower cognitive

and language scores and more behavioral problems. Both internalizing and externalizing behavior prob-

lems were most common in the USN group. Externalizing behavior problems predicted parenting stress.

Higher IQ could be predicted by language scores and an absence of externalizing behavior problems.

When comparing the two neglect groups, shorter time spent in a stable environment, lower scores on lan-

guage skills, and the presence of externalizing behavior predicted lower IQ. Conclusion: These findings

emphasize the importance of early stable, permanent placement of children who have been in neglectful

and pre-adoptive international settings. While an enriching environment may promote resilience, children

who have experienced early neglect are vulnerable to cognitive, language and behavioral deficits and

neurodevelopmental and behavioral evaluations are required to identify those in need of intervention.

Keywords: International Adoption; Child Neglect; Childhood Adversity

Introduction on intelligence and language tests [17-19]. A study including

33 mother-child dyads found that children with a history of

Neglect is the most prevalent form of child maltreatment in

neglect scored significantly lower on measures of syntactic

the United States [1] and has been associated with negative

ability and receptive vocabulary when age and maternal IQ

social, behavioral, and cognitive consequences [2,3]. In addi-

were controlled [18]. A 2001 study found progressive cognitive

tion to physical and emotional neglect in a home setting, ne-

decline in children experiencing substantiated neglect in com-

glect can take place in international institution environments

parison to non-neglected children [19]. Children reared in in-

where a lack of consistent caregivers, crowded conditions, and

too few employees may lead to an infant or toddler not having stitutional settings fall victim to similar risk factors; there are

their physical, social, and/or emotional needs met [4]. Early poor child-caregiver ratios, inadequate cognitive, sensory, and

childhood is a vulnerable period for the acquisition and devel- linguistic stimulation, and unresponsive care-giving practices

opment of cognitive, language, and emotion regulation abilities, [20]. Therefore, the children may exhibit delays in development

and therefore neglect in early childhood is of particular concern of IQ, language, and social emotional functioning as well as

[5]. Normal development may be disrupted by deprivation as- impaired attachment [21-24].

sociated with neglect and can result in dysregulation of neural The purpose of the current study was to compare cognitive,

systems during vulnerable periods of brain development [6-9], language, and behavioral functioning of children with no his-

leading to pronounced neurocognitive deficits due to maltreat- tory of neglect to children with early neglectful situations, spe-

ment [10-13]. cifically those who experience physical and emotional neglect

Low-stimulation environments and inconsistent parenting from a caregiver or deprivation due to pre-adoptive placement

(lack of rules, failure to monitor child, inconsistent punishment in an international institution environment. This study exam-

and reward) [14], common in both physical neglect environ- ined children who had the experience of international institution

ments and orphanage setting [15,16], can lead to lower scores life and were then adopted into higher socioeconomic status

(SES) households. This international adoption group was com- pared

*

Corresponding author. with United States born children with a history of physi-

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 175

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

cal or emotional neglect. These children remained in a similar referred by medical or mental health practitioners or were

SES when placed in an extended family member’s household self-referred after reviewing flyers. The caregivers signed a

(grandmother, great aunt) post-removal from neglectful envi- release of information form to obtain educational, medical

ronment. Both neglect groups (international adoption and US (birth records, prenatal care of mother, and ongoing medical

neglect) were also compared to a control group of United and mental health care), and adoption records. Families were

States-born children without a history of neglect. interviewed to clarify details about the child’s clinical and ne-

Following previous research on the effects of neglect and glect history. All participants signed a release to allow access to

child resilience [20,25], we hypothesized that the control group the state’s Child Protective Services (CPS) records to assure

would have significantly better scores than either of the neglect that controls had no abuse or neglect history and to obtain addi-

groups on all cognitive, language, and behavioral measures. It tional details on cases that were involved with CPS. For clari-

was also hypothesized that adopted children would have lower fication, Child Protective Services is a government agency in

language scores but less behavior problems and parental stress many states that responds to reports of child abuse or neglect.

than US neglect children. In the neglect groups, we predicted The Department of Social Services includes CPS, as well as

that behavior problems would be associated with parental stress, assistance with Medicaid, child support, public housing, foster

and that a longer time in a non-neglectful environment would care, adoptions, Adult Protective Services, and a supplemental

account for any differences in externalizing and internalizing nutrition assistance program. Once informed consent was ob-

symptoms between the two neglect groups. tained, children and their caregivers attended an appointment at

the CTRC outpatient clinic where the child underwent a physi-

Methods cal examination, which included vital signs, head circumfer-

ence, height, weight and collection of serum, urine, and saliva.

Design Standardized measures of language and cognitive abilities were

A cohort of 60 children was divided into three groups: 1) US administered to children, and caregivers completed question-

children with a history of physical or emotional neglect as de- naires assessing child behavioral functioning and parental stress.

fined by the Barnett Child Maltreatment Classification Scheme Psychometric and cognitive evaluations were administered by a

(MCS) [26] (USN); 2) children adopted from international in- licensed psychologist.

stitutions (IA); and 3) US children with no history of neglect,

abuse, or adoption (Control). Measures

All tests administered were standardized, and testing was al-

Participants ways done with a measure appropriate for the participant’s age.

Participants were between the ages of three and ten years. Cognitive functioning. The Differential Abilities Scale for

Seventeen children met criteria for the USN group and were Children (DAS): Third Edition [28] is a standardized cognitive

living with a care-giving relative, a rehabilitated offending assessment for children between 2 years 6 months and 17 years

parent, or a non-offending parent at the time of the study. Fif- 11 months [28] and is particularly useful when testing children

teen children met criteria for the IA group; one child was from in the late toddler and early childhood range. The DAS yields

a Central American foster home and the rest were from Eastern 17 cognitive and 3 achievement subtest scores and enables

European institutions. These children were living with their identification of a child’s cognitive capabilities with a score for

adoptive families at the time of the study. Twenty-eight chil- General Conceptual Ability (GCA). The GCA is derived from

dren had neither experienced neglect nor out-of-home place- only those subtests which have high correlations to overall

ment and met criteria for the control group. general abilities. The cluster scores yield broad measures of

Participants with any of the following conditions were ex- verbal ability, nonverbal reasoning ability, and general concep-

cluded from the study: 1) malnutrition as indicated by Centers tual ability (GCA) [29]. The standard scores, ranging from 20

for Disease Control charts [27] (weight adjusted for stature <1st to 80, for each subtest are based on age with a mean of 50 and a

percentile); 2) morbid obesity (Body Mass Index over 40); 3) standard deviation of 10. Percentiles may also be expressed.

birth complications (birth weight <2500 g, gestational age <37 Language functioning. The Test of Early Language Devel-

weeks, or respiratory distress syndrome); 4) IQ below 70; 5) opment: Third Edition (TELD) [30] is a standardized, norm-

neurobiological disorders (Cerebral Palsy, Childhood Schizo- referenced test that was designed to measure the expressive and

phrenia, Autism, Morbid Obesity, or Central Nervous System receptive language development of children ages 2 through 6

Disorders); 6) known in-utero substance exposure that led to a years 11 months. Standard scores are provided for Receptive

prolonged hospital stay for the infant or, 7) a serious medical Language, Expressive Language, and an overall Oral Language

condition. It is also important to note that children in current Composite. A standard score has a mean of 100 and a standard

Child Protective Services (CPS) and/or foster care were ex- deviation of 15, and percentiles are usually listed for clarifica-

cluded from the study because the state agency would not give tion. All participants in the international adoption group had to

permission to do research with this population. meet language competency skills to participate in the study.

Children above the TELD age range were given the Test of

Research Procedures Language Development (TOLD). If the children were between

the ages 7 to 9 years, they were given the TOLD-Primary. This

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board assessment looks at nine sub-categories of oral language com-

(IRB) at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and petency and is approved for children ages 4 to 9 years. If the

sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the MUSC children were above 9 years old, they were given the TOLD-

Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC). Intermediate. This assessment examines six sub-tests and is

Children and their caregivers participating in the study were approved for children ages 8 to 18 years old. Both the TOLD-

176 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

Primary and the TOLD-Intermediate are used to assess the oral It is important to note that these measurements, evaluations,

language proficiency of children [31]. and parental reports were obtained after all neglected children

Behavioral functioning. The Child Behavior Checklist were placed in a stable, non-neglectful environment for at least

(CBCL) [32], measures caregiver ratings of behavioral and a year by adoptive parents or a relative. The IA group had an

emotional functioning of children ages 1 1/2 to 18 and includes average time of 51.6 months in a stable environment, and the

three broad band behavior problem scales: Internalizing, Ex- USN had an average time of 27.5 months. The control group

ternalizing, and Total. Subscales include withdrawn, anxious/ participants had always been living in a stable environment.

depressed, somatic complaints, attention problems and aggres- Although spending time in a stable environment prior to testing

sive behavior. The score on each syndrome is derived from may be seen as a limitation, the time frame could have served

summing the numbers circled by the parent. The percentile of as an adjustment period to better understand the long term per-

the national normal sample for each syndrome score is used vasive and more deeply rooted cognitive, emotional and be-

through comparison to give a T score. Using the T score, prac- havioral concerns.

titioners are able rank the child’s score and percentile as com- Statistical Analysis

pared to thousands of other same gender and age children. For SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc.) or SPSS (version

example, if a child was at the 69th percentile, then 69% of the 16.0.1, SPSS, Inc.) statistical programs were used for all analy-

children in the national normative sample scored either at or ses. Student’s t-test or ANOVA were used to compare means of

below this score. There are several cutoffs for normal range, normally distributed continuous variables. Chi Square or

borderline range, and clinical range to categorize behavior Fisher’s Exact test were used to assess group differences in

problems. categorical variables. ANCOVA (controlling for annual house-

Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF) [33]. The PSI Short Form is hold income) was used to compare the three groups on meas-

a 36-item parent self-report instrument containing three fac- ures of cognitive ability, language ability, behavioral issues,

tor-analytically-derived subscales (Parental Distress, Parent- and parenting stress. Multiple Linear Regression was used to

Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult Child) and a examine predictive models while simultaneously adjusting for

Total Stress score. Each subscale consists of 12 items that can potential confounding variables.

be rated from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). It is a

sound, brief screening measure of parenting stress where higher Results

scores on subscales and total scores indicate greater amounts of

stress. Demographic and environmental variables are reported in

Child Maltreatment—Neglect. Measurements used to deter- Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups

mine neglect and other maltreatment summary variables were on race, age, or gender. USN group members were older at the

obtained from archival record data including CPS, medical, time of placement with a relative, non-offending or rehabili-

mental health and institutional records. After reviewing archival tated offending caregiver, t(30) = 2.82, p = .008. These children

data and interviewing the current guardian, investigators deter- had spent a larger proportion of time in the unstable environ-

mined whether the child experienced neglect (physical or med- ment than the IA group, t(30) = 3.11, p = .004. The time spent

ical) and/or abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional). It was also in the current home (defined as a stable environment) prior to

noted if the child witnessed domestic violence. Out of the 32 study participation was greater for children in the IA than USN

children from the international adoption and US neglect groups group, t(30) = 4.13, p =. 010. It is however suspected that the

combined, it was known that 8 (25%) had a previous caregiver deprivation was more chronic and severe during the first year(s)

who abused drugs, 11 (34.4%) who abused alcohol, and 13 of life for the IA group. Although it is challenging to describe

(40.6%) who smoked in utero. In reference to the neglect and and control for a stable environment (in the control group as

abuse findings, 18 (56.3%) children were known to have ex- well as the neglect groups), the term is used to describe the

perienced physical neglect, 6 experienced medical neglect households who have no recent reports of child neglect or abuse

(18.8%) (with 4 being from no prenatal care), 7 (21.9%) ex- and have parents or caretakers concerned enough for these

perienced physical abuse, 1 (3.1%) experienced sexual abuse, children to be seen in medical or mental health clinics. No sig-

and 3 (9.4%) experienced emotional abuse. Seven (21.9%) nificant concerns were identified when the project study coor-

children witnessed domestic violence. dinator visited the home to obtain the informed consent. When

Table 1.

Demographic information.

Control US IA

Gender Male = 15; Female = 13 Male = 8; Female = 9 Male = 9; Female = 6

Race White = 20; Black = 6; Other = 2 White = 12; Black = 2; Other = 3 White = 14; Other = 1

Age (in months) M = 67; SD = 21.4 M = 64; SD = 26.9 M = 73; SD = 12.7

M = 120,466;

Annual household income M = 109,019; SD = 54,995 M = 37,889; SD = 22,031

SD = 68,376

Age at time of removal from neglectful

M = 32.1; SD = 15.5 M = 20.7; SD = 13.0

environment (in months)

Proportion of life in neglectful

M = 55.8%; SD = 24.9% M = 30.9%; SD = 19.8%

environment

Time in current home (in months) M = 28.8; SD = 17.3 M = 51.7; SD = 28.8

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 177

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

studying people and their home environments, there are limita- Total Problems (p < .001) subscales.

tions to knowing the specifics of the household and to knowing

their constant activity. The inability to measure a “stable envi- USN v. IA

ronment” in any way other than home observation and medical

record review could be considered a limitation of this study. The USN group scored significantly higher than the IA group

The three groups differed on annual household income, F(2,57) on CBCL Anxiety and Depression (p = .009), Attention (p

= 10.48, p < .0001, with the USN group having significantly = .002), Aggression (p = .001), Internalizing (p = .02), Exter-

lower current income than IA (p < .0001) and healthy controls nalizing (p = .01), and Total Problems (p = .02) subscales.

(p = .008).

As shown in Table 2, when controlling for annual household Correlations

income using analysis of covariance, the USN, IA, and Control When USN and IA groups were combined to form one child

groups differed significantly on measures of cognitive and lan- neglect (CN) group, there were significant positive correlations

guage functioning, behavior problems, and parenting stress. between time in stable environment and scores on the DAS

Significant group differences were explored as reported below. GCA scale (r = .468, p = .014) and the DAS nonverbal scale (r

=.451, p = .021). Considering the USN group individually,

Control v. USN there were significant positive correlations between time in

The control group performed significantly better than the stable environment and DAS GCA (r = .535, p = .027) and

USN group on the DAS nonverbal (p = .05) and GCA (p = .008) DAS nonverbal (r = .630, p = .007). Considering the IA group

subscales as well as the TELD receptive (p = .004), expressive individually, a significant positive correlation was observed

(p = .006), and Oral Composite (p = .002). The USN group between time in neglectful environment and CBCL internaliz-

scored significantly higher than controls on the CBCL Atten- ing subscale (r = .542, p = .037).

tion (p < .0001), Aggression (p < .0001), Anxiety and Depres-

sion (p < .0001), Internalizing (p < .0001), Externalizing (p Multiple Regression

< .0001), and Total Problems (p < .0001) subscales as well as

A series of five multiple linear regression models was de-

the PSI Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscale (p

veloped to examine the predictors of outcome on the DAS GCA,

< .0001).

PSI Total Stress scale, CBCL Internalizing, and CBCL Exter-

nalizing scales and to compare US, IA, and control groups.

Control v. IA Variables included in each model are listed in Table 3.

Children in the control group performed significantly better Model 1 revealed that 78% of the variance in scores on the

than children in the IA group on DAS verbal (p = .04) and DAS GCA could be accounted for by scores on the TELD Oral

GCA (p = .003) as well as TELD receptive (p = .002), expres- composite scale and CBCL Externalizing subscale. Model 2

sive (p < .001) and Oral Composite (p < .001). The IA group explained that 62% of variance in PSI Total Stress scores was

exhibited significantly higher scores on the CBCL Attention (p accounted for by scores on the CBCL externalizing subscale.

= .002), Internalizing (p = .026), Externalizing (p = .03) and Being a member of either the USN or IA groups was not pre-

Table 2.

ANCOVA comparison of US, IA, and control on cognitive, language, and behavioral functioning with means adjusted for income.

Control US IA MSE F P

Least Squares Mean

DAS Verbal 97.77 90.44 87.33 12.40 3.74 .018

DAS Nonverbal 107.16 95.96 97.62 14.56 3.46 .025

DAS GCA 104.41 92.12 89.97 12.30 10.56 <.0001

TELD Receptive 106.14 92.40 90.49 12.74 9.33 <.0001

TELD Expressive 100.13 87.64 83.71 12.01 8.96 .0001

Oral Composite 103.84 87.76 84.00 13.50 10.69 <.0001

PSI-PCDI 17.05 28.09 20.41 7.11 7.07 .0004

CBCL Anxiety Depression t-score 51.16 61.24 54.57 5.94 9.48 <.0001

CBCL Attention t-score 51.63 67.59 58.84 6.57 21.38 <.0001

CBCL Aggression t-score 51.38 70.98 55.69 10.61 9.95 <.0001

CBCL Internalizing t-score 44.49 61.83 52.21 10.09 11.63 <.0001

CBCL Externalizing t-score 44.77 65.26 53.03 11.11 12.03 <.0001

CBCL Total t-score 43.33 66.02 55.80 10.36 18.41 <.0001

Note: DAS = Differential Abilities Scale; DAS GCA = Differential Abilities Scale General Conceptual Ability; TELD = Test of Early Language Development;

PSI-PCDI = Parenting Stress Index-Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

178 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

Table 3. time in a stable environment on the DAS GCA.

Multiple linear regression models 1 - 5.

Variable β Standard Error T P

Discussion

Model 1: Dependent Variable DAS GCA*

As hypothesized, when controlling for SES, children in the

control group exhibited higher levels of cognitive, language,

TELD Oral Composite .71 .08 9.00 <.0001 and behavioral functioning than both neglect groups, and the IA

CBCL Internalizing Subscale –.03 .13 –.23 .91 group exhibited better behavioral adjustment than the USN

group. The greatest differences in behavioral and cognitive

CBCL Externalizing Subscale –.25 .12 –2.01 .05 measures were found between the USN and control groups.

USN 1.88 3.28 .57 .56 As children develop, the neurocognitive deficits associated

with adverse early life events can impair functioning and in-

IA 1.43 3.15 .45 .65 crease the vulnerability for social and behavioral difficulties. A

Model 2: Dependent Variable PSI Total Stress * cross-sectional study of 420 children indicated that those with a

history of maltreatment performed more poorly in school than

TELD Oral Composite .28 .17 1.67 .10 their non-maltreated counterparts [34]. When controlling for

CBCL Internalizing Subscale .39 .28 1.39 .17 age, maltreated children had lower grades and more suspen-

sions, disciplinary referrals, and grade repetitions in elementary,

CBCL Externalizing Subscale 1.11 .27 4.18 .0001 junior high, and senior high school [34].

USN 3.20 6.92 .46 .65 Neglect is the type of maltreatment most strongly associated

with delays in expressive, receptive, and overall language de-

IA –1.78 6.66 –.27 .79 velopment [35]. Slow language development plays a role in

Model 3: Dependent Variable CBCL Internalizing * behavioral difficulties across the life span, with approximately

70% of children with language impairments exhibiting co-morbid

DAS GCA –.35 .19 –1.85 .07 behavior problems [36]. Children who are unable to communi-

TELD Oral Composite .11 .18 .62 .53 cate effectively may not have the necessary skills to negotiate

or resolve conflict and may have difficulties understanding and

USN 12.93 3.89 3.33 .0017

relating to others. Psychiatric disorders such as attention-deficit/

IA 2.22 4.27 .52 .61 hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, conduct disorder,

*

and oppositional defiant disorder are highly associated with

Model 4: Dependent Variable CBCL Externalizing

language impairment, and a combination of these problems

DAS GCA –.53 .19 –2.79 .0076 may lead to poor social functioning as these individuals enter

adulthood [36]. Although the current sample of USN children

TELD Oral Composite .22 .18 1.24 .22

had difficulties in all realms tested, it may be that impaired

USN 13.96 3.97 3.51 .0010 language development, as determined by the USN children’s

significantly lower scores on all subscales of the TELD as

IA .40 4.37 .09 .93

compared to controls, is contributing to the higher number of

**

Model 5: Dependent Variable DAS GCA behavior problems in the USN group.

Children with a history of neglect are at risk for impaired

TELD Oral Composite .71 .13 5.18 <.0001

language development if they are not provided the complex

CBCL Internalizing Subscale .24 .17 1.41 .17 linguistic input and personal interactions necessary for optimal

development of language skills. Studies have shown that the

CBCL Externalizing Subscale –.29 .15 –2.00 .06

quality of mother-child interactions help predict cognitive and

Time in Neglectful Environment .12 .13 .89 .38 linguistic outcomes in preschool-aged children of high social

risk mothers [37]. Interpersonal interaction is necessary for the

Time in Stable Environment .40 .14 2.87 .009

acquisition of early language [38], and these interactions may

USN –1.55 3.69 –.42 .68 be limited for children that have been in institutional settings

* ** [39] or have experienced physical or emotional neglect [18]. In

Controls included as intercept. IA included as intercept. Note: DAS GCA =

Differential Abilities Scale Global Conceptual Ability; TELD = Test of Early addition to the hardships of neglectful environments, children

Language Development; USN = US born neglect group; IA = International adop- adopted internationally are also at risk for deficits in language

tion group. acquisition due to the challenges of learning a new language

[40].

dictive of scores on the DAS GCA or PSI Total Stress scale. In the current study, children in the IA group were living in

Model 3 showed that being in the USN group significantly homes with higher annual household incomes than children in

predicted scores on the CBCL Internalizing subscale account- the USN group, which may have provided greater opportunities

ing for 41% of variance. Model 4 revealed that scores on the for enrichment and subsequent cognitive, language, and behav-

DAS GCA and being a member of the USN group explained ioral development. Juffer and van Ijzendoorn (2005) found

49% of the variance in externalizing behavior. Model 5 includ- similar behavioral results when comparing children adopted

ing only USN and IA groups was created to examine the pre- internationally with children adopted domestically and deduced

dictive value of time in a stable environment on DAS GCA that parents of international adoptees tend to have more finan-

scores. This model explained 71% of the variance with the cial resources to invest in the child’s development, which may

TELD oral composite scale and predicting scores related to be a contributing factor to their having fewer behavioral prob-

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 179

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

lems [41]. Consistent with the demographic information of our sequent research studies.

study sample, low income is strongly associated with child In the small number of studies examining deprivation due to

abuse and neglect [42], and children living in poverty are ex- institutionalization, internationally adopted children have dem-

posed to environmental hazards such as violence, hunger, infe- onstrated difficulties with attention, language, and aggression

rior health care, and few recreational opportunities [43]. Al- similar to children experiencing physical neglect [55,56]. A

though both IA and USN children were exposed to neglectful strength of this study is that to date, no published studies have

environments in early childhood, the placement of IA children compared neglected children from the United States who live

in higher income families may have provided an environment with their relatives or foster families to children who have ex-

that promoted resilience from adversity. Factors that promote perienced early deprivation in an institution. Understanding the

resilience for children that have experienced abuse and neglect differential impact of these two kinds of deprivation and ne-

include structured school environment, involvement in extra- glect may help with the development of family-based interven-

curricular activities and the religious community, and a suppor- tions for these and other populations experiencing adverse

tive adult providing emotionally responsive care-giving [44]. childhood events.

Numerous studies have examined the association between ne- Despite a small sample size, there were statistically signifi-

glect and poverty as well as poverty and child outcomes [45]; cant findings which emphasize the prevalence and severity of

however, little research has investigated the association be- the issues addressed. However, all behavioral participant in-

tween neglect and child outcomes as mediated by annual formation obtained was by parental report (not by a blinded

household income. This enrichment of cognitive and language rater or outside observer) and therefore might reflect the view

skills that often accompanies higher SES status in turn may only of the parent. Some of the limitations faced included the

have helped to provide protection from behavioral problems challenge of assessing the severity and chronologic sequence of

[46]. In addition, the perceived variance in language scores neglect, institutions differing in the quality of care, adoptive

between the USN group and the children in the IA and control parents being more tolerant of negative behaviors, and possible

groups may be due in part to parental language and education incomplete historical records. We cannot exclude other types of

level. maltreatment that play a role in the outcomes of this study, but

Externalizing behavioral problems of children play a primary the predominant insult for these young children was a history of

role in elevating stress levels for parents, particularly in con- physical neglect and less than optimal care. Children in current

junction with perceived inadequacy of support and/or resources child protective services and foster care were not involved in

[47]. The current study revealed an association between behav- this study, leaving out the more severe US neglect cases. Future

ior problems and parenting stress, consistent with prior research studies would benefit from unbiased child behavioral data

[48-51]. Hung et al. (2004) [52] suggests that quantifying pa- through reliable coders, teachers, and whenever possible, care-

rental distress is an essential part of a diagnostic assessment for giver and child self-report measures.

young children with special needs. Parent support groups and In closing, some researchers have written of the “neglect of

parenting education courses have proved to be useful interven- neglect” [45]. In the maltreatment field, there has been a ten-

tion strategies for stressed parents [53]. Since there is often dency to focus on physical and sexual abuse leaving many cli-

great diversity in the families of children with a history of ne- nicians and educators with poor understanding of the potential

glect or international adoption, successful interventions might impact of neglect on a young child’s cognitive, language, and

include components addressing parental coping styles and sup- behavioral development. Neglect may be the most detrimental

port in dealing with behavioral challenges. Because the current maltreatment type on brain development [6,57,58]. As this

study relied on parental report at least 1 year post-placement in study indicates, environment post-neglect may serve as a buffer

stable environment, it is unclear whether child behavior prob- for some problems, and children from a neglectful environment

lems exacerbated parental stress or vice versa. Associations require more intervention than placement in a non-neglectful

between IQ and behavior problems can lead to increased pa- home. Multifaceted interventions addressing cognitive, lan-

rental stress, or stressed parents may cause children to exhibit guage and behavioral difficulties are needed to maximize the

more behavior problems. The findings that neglected children optimum potential in each of these children.

perform more poorly on tests of cognition and have signifi-

cantly elevated behavior problems reflect to the need for earlier Acknowledgements

evaluations and interventions for children with a history of

neglect. NIH/NIMH K23MH064111: Neurodevelopmental Biology

Time in a stable environment does appear to be protective as of Neglected Children (PI: Eve G. Spratt). NIH/NIDA K24DA

there was a positive association with measures of cognitive 00435: Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Re-

ability in the USN group. These findings support the recom- search (PI: Kathleen T. Brady). NIH/NIMH K24MH71434:

mendations of Nelson et al. (2007) that intervention as early as Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (PI:

possible through placement in a nurturing environment yields Michael D. De Bellis). Special thanks to: Medical University of

improved outcomes such as increase in cognitive ability [20]. South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Center;

Our suspicions are that the periods of deprivation were longer Pam Ingram, M. Ed, Josie Kirker, MSW, Loriann Ueberroth

and more chronic for those in an institution vs a neglectful and Mary Kral, PhD.

home. One study has found that children with a history of ne-

glect that do not return to biologic parents may fare best [54].

The influence of time spent in neglectful environments on be- REFERENCES

havioral and cognitive impairment, as well as a closer examina- Child Welfare Information Gateway (2009). Strengthening families and

tion of factors that appear to be protective against neurodevel- communities: 2009 resource guide. US Department of Health and

opmental and behavioral problems, should be the focus of sub- Human Services.

180 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

Cahill, L. T., Kaminer, R. K., & Johnson, P. G. (1999). Developmental prospective study. Pediatrics, 108, 142-151.

cognitive and behavioral sequelae of child abuse. Child and Adoles- doi:10.1542/peds.108.1.142

cent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 8, 827-843. Nelson III, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., Fox, N. A. et al. (2007). Cognitive

Pynoos, R., Steinberg, A. M., & Wraith, R. (1995). A developmental recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest early

model of childhood traumatic stress. In D., Cicchetti, & J. Cohen intervention project. Science, 318, 1937-1940.

(Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (pp. 72-95). New York: John doi:10.1126/science.1143921

Wiley and Sons. Gunnar, M. R. (2001). Effects of early deprivation: Findings from

Zeanah, C. H., Smyke, A. T., & Dumitrescu, A. (2002). Attachment orphanage-reared infants and children. In: C. H. Nelson, & M. Luci-

disturbances in young children. II: Indiscriminate behavior and insti- ana (Eds.), Handbook of developmental neuroscience. Cambridge,

tutional care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Ado- MA: MIT Press.

lescent Psychiatry, 41, 983-989. Morison, S. J., Ames, A., & Chisholm, K. (1995). The development of

doi:10.1097/00004583-200208000-00017 children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Merrill-Palmer Quar-

Munakata, Y., Casey, B. J., & Diamond, A. (2004). Developmental terly, 41, 411.

cognitive neuroscience: Progress and potential. Trends in Cognitive Rutter, M. (1998). Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following

Sciences, 8, 122-128. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.01.005 adoption after severe global early privation. Journal of Child Psy-

Perry, B. D. (2001). The neuroarcheology of childhood maltreatment: chology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 39, 465.

The neurodevelopmental costs of adverse childhood events. In: B. doi:10.1017/S0021963098002236

Geffner (Ed.), The cost of child maltreatment: Who pays? We all do. Zeanah, C. H., Nelson, C. A., Fox, N. A. et al. (2003). Designing re-

San Diego: Family Violence and Sexual Assault Institute. search to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behav-

Perry, B. D., Pollard, R. A., Blakley, T. L. et al. (1995). Childhood ioral development: The Bucharest early intervention project. Devel-

trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and “use-dependent” devel- opment and Psychopathology, 15, 885-907.

opment of the brain: How “states” become “traits”. Infant Mental doi:10.1017/S0954579403000452

Health Journal, 16, 271-291. Hildyard, K. L., & Wolfe, D. A. (2002). Child neglect: Developmental

doi:10.1002/1097-0355(199524)16:4<271::AID-IMHJ2280160404> issues and outcomes [small star, filled]. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26,

3.0.CO;2-B 679-695. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00341-1

Pollak, S., Cicchetti, D., Klorman, R. et al. (1997). Cognitive brain Barnett, D., Manly, J. T., & Cicchetti, D. (1993). Defining child mal-

event-related potentials and emotion processing in maltreated chil- treatment: The interface between policy and research. In D. Cicchetti,

dren. Child Development, 68, 773-787. & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Child abuse, child development, and social pol-

doi:10.2307/1132032 icy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Wismer, F. A., Shirtcliff, E., & Pollak, S. (2008). Neuroendocrine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000). 2000 CDC growth

dysregulation following early social deprivation in children. Devel- charts for the United States: Methods and development. Hyattsville,

opmental Psychobiology, 50, 588-599. MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

doi:10.1002/dev.20319 Elliott, C. D. (1990). Differential ability scales. In C. D. Elliott (Ed.),

Eckenrode, J., Laird, M., & Doris, J. (2005). School performance and Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psycho-

disciplinary problems among abused and neglected children. Devel- logical Corporation.

opmental Psychology, 29, 53-62. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.53 Aylward, G. P. (1994). Practitioner’s guide to developmental and psy-

Pears, K., & Fisher, P. A. (2005). Developmental, cognitive, and neu- chological testing. New York, London: Plenum Medical Book Com-

ropsychological functioning in preschool-aged foster children: Asso- pany.

ciations with prior maltreatment and placement history. Develop- Hresko, W., Reid, D., & Hammill, D. (1981). The test of early language

mental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 26, 112-122. development. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

doi:10.1097/00004703-200504000-00006 Hammill, D., & Newcomer, P. (2010). Speech and language assess-

Prasad, M. R., Kramer, L. A., & Ewing-Cobbs, L. (2005). Cognitive ments. URL (last checked 19 August 2010).

and neuroimaging findings in physically abused preschoolers. Ar- http://www.psych-edpublications.com/speech.htm#toldp

chives of Disease in Childhood, 90, 82-85. Achenbach, T. M. (1991). The child behavior checklist. Burlington, VT:

doi:10.1136/adc.2003.045583 University of Vermont.

Lee, V., & Hoaken, P. N. S. (2007). Cognition, emotion, and neurobio- Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting stress index-short form. Charlottesville,

logical development: Mediating the relation between maltreatment VA: Pediatric Psychology Press.

and aggression. Child Maltreatment, 12, 281-298. Kendall-Tackett, K. A., & Eckenrode, J. (1996). The effects of neglect

doi:10.1177/1077559507303778 on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: A develop-

Gardner, F. E. M. (1989). Inconsistent parenting: Is there evidence for a mental perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20, 161-169.

link with children’s conduct problems? Journal of Abnormal Child doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(95)00139-5

Psychology, 17. Culp, R. E., Watkins, R. V., Lawrence, H. et al. (1991). Maltreated

O’Connor, T. G., Rutter, M., & ERA Study Team (2000). Attachment children’s language and speech development: Abused, neglected, and

disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: Extenstion and abused and neglected. First Language, 11, 377-389.

longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child doi:10.1177/014272379101103305

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 703-712. Im-Bolter, N., & Cohen, N. J. (2007). Language impairment and psy-

doi:10.1097/00004583-200006000-00008 chiatric comorbidities. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 54, 525-

Groark, C. J., Muhamedrahimov, R. J., Palmov, O. I. et al. (2005). 542. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.02.008

Improvements in early care in Russian orphanages and their rela- Kelly, J. F., Morisset, C. E., Barnard, K. E. et al. (1996). The influence

tionship to observed behaviors. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, of early mother-child interaction on preschool cognitive/linguistic

96-109. doi:10.1002/imhj.20041 outcomes in a high-social-risk group. Infant Mental Health Journal,

Eisen, M. L., Goodman, G. S., Qin, J. et al. (2007). Maltreated chil- 17, 310-321.

dren’s memory: Accuracy, suggestibility, and psychopathology. De- doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199624)17:4<310::AID-IMHJ3>3.0.C

velopmental Psychology, 43, 1275-1294. O;2-Q

doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1275 Nicely, P., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Bornstein, M. H. (1999). Moth-

Eigsti, I. M., & Cicchetti, D. (2004). The impact of child maltreatment ers’ attuned responses to infant affect expressivity promote earlier

on expressive syntax at 60 months. Developmental Science, 7, achievement of language milestones. Infant Behavior and Develop-

88-102. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00325.x ment, 22, 577-568. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00023-0

Strathearn, L., Gray, P. H., & Wood, D. O. (2001). Childhood neglect Windsor, J., Glaze, L. E., Koga, S. F. et al. (2007). Language acquisi-

and cognitive development in extremely low birth weight infants: A tion with limited input: Romanian institution and foster care. Journal

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 181

E. G. SPRATT ET AL.

of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1365-1381. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 24, 267-275.

doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2007/095) doi:10.1097/00004703-200308000-00008

Glennen, S. (2005). New arrivals: Speech and language assessment for Ong, L. C., Chandran, V., & Boo, N. Y. (2001). Comparison of parent-

internationally adopted infants and toddlers within the first months ing stress between Malaysian mothers of four-year-old very low

home. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 10-21. birthweight and normal birthweight children. Acta Paediatrica, 90,

doi:10.1055/s-2005-864212 1464-1469. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2001.tb01614.x

Juffer, F., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behavior problems and Raina, P., O’Donnell, M., Rosenbaum, P. et al. (2005). The health and

mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics,

Jama, 293, 2501-2515. doi:10.1001/jama.293.20.2501 115, 626-636. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1689

Sedlak, A. J., & Broadhurst, D. D. (1996). Third national incidence Hung, J., Wu, Y., & Yeh, C. (2004). Comparing stress levels of parents

study of child abuse and neglect. Washington DC: US Department of of children with cancer and parents of children with physical dis-

Health and Human Services. abilities. Psycho-Oncology, 13, 898-903.

Parker, S. W., Greer, S., & Zuckerman, B. (1988). Double jeopardy: doi:10.1002/pon.868

The impact of poverty on early child development. Pediatric Clinics Hartman, A. F., Radin, M. B., & McConnell, B. (1992). Parent-to-

of North America, 35, 1227. parent support: A critical component of health care services for fami-

Heller, S. S., Larrieu, J. A., D’Imperio, R., & Boris, N. W. (1999). lies. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 15, 55-67.

Research on resilience to child maltreatment: Empirical considera- doi:10.3109/01460869209078240

tions. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23, 321-338. Taussig, H. N., Clyman, R. B., & Landsverk, J. (2001). Children who

doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00007-1 return home from foster care: A 6-year prospective study of behav-

Dubowitz, H., Papas, M. A., Black, M. M. et al. (2002). Child neglect: ioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics, 108, e10.

Outcomes in high-risk urban preschoolers. Pediatrics, 109, 1100- doi:10.1542/peds.108.1.e10

1107. doi:10.1542/peds.109.6.1100 Rosnati, R., Montirosso, R., & Barni, D. (2008). Behavioral and emo-

Noble, K., McCandliss, B., & Farah, M. (2007). Socioeconomic gradi- tional problems among Italian international adoptees and non-

ents predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. De- adopted children: Father’s and mother’s reports. Journal of Family

velopmental Science, 10, 464-480. Psychology, 22, 541-549. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.541

doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x Beverly, B. L., McGuinness, T. M., & Blanton, D. J. (2008). Commu-

Spratt, E. G., Macias, M. M., & Saylor, C. F. (2007). Assessing parent- nication and academic challenges in early adolescence for children

ing stress in multiple samples of children with special needs (CSN). who have been adopted from the former Soviet Union. Language,

Families, Systems, and Health, 25, 435-449. Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 303-313.

doi:10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.435 doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2008/029)

Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., Crnic, K. A. et al. (2002). Behavior problems Sanchez, M. M., Noble, P. M., Lyon, C. K. et al. (2005). Alterations in

and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and diurnal cortisol rythm and acoustic startle response in nonhuman

without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retar- primates with adverse rearing. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 373-381.

dation, 107, 433-444. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.032

doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0433:BPAPSI>2.0.CO;2 Harlow, H. F., & Harlow, M. K. (1973). Social deprivation in monkeys.

Johnston, C., Hessl, D., Blasey, C. et al. (2003). Factors associated with Readings from the scientific American: The nature and nurture of

parenting stress in mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. behavior. San Francisco: WH Freeman Co.

182 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

View publication stats

You might also like

- A level Psychology Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsFrom EverandA level Psychology Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Emotional, Academic, Cognitive and Social Condition of Orphans in Asilo de San Vicente de Paul: A Case StudyDocument26 pagesThe Emotional, Academic, Cognitive and Social Condition of Orphans in Asilo de San Vicente de Paul: A Case StudyBlythe BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Nihms 264660Document23 pagesNihms 264660Miguel DebonoNo ratings yet

- Children With Cochlear Implants and Their ParentsDocument11 pagesChildren With Cochlear Implants and Their ParentsBayazid AhamedNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument24 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptRicardo Vio LeonardiNo ratings yet

- 4 Ijeefusfeb20174Document6 pages4 Ijeefusfeb20174TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentDocument18 pagesEmotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentLoredana Pirghie AntonNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Outcomes in Young ChildrenDocument14 pagesPsychiatric Outcomes in Young ChildrencameliamorariuNo ratings yet

- Nihms 79342Document19 pagesNihms 79342Luis CortesNo ratings yet

- TRICIAMYLOVESDocument7 pagesTRICIAMYLOVEShalisonhanzurezNo ratings yet

- BM 3.5 IGA Trisna WindianiDocument45 pagesBM 3.5 IGA Trisna WindianiAbdullah ShiddiqNo ratings yet

- Parental Characteristics, Parenting Style, and Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Children With Down Syndrome, Their Siblings and Controls in TaiwanDocument11 pagesParental Characteristics, Parenting Style, and Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Children With Down Syndrome, Their Siblings and Controls in Taiwanrifka yoesoefNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Emotional Symptoms of Post-Institutionalized Children in Middle ChildhoodDocument9 pagesBehavioral and Emotional Symptoms of Post-Institutionalized Children in Middle ChildhoodAniriiiNo ratings yet

- 5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018Document20 pages5 - Perry, R.E. - 2018João PedroNo ratings yet

- Lack of Parental Supervision and Psychosocial Development of Children of School Going Age in Buea Sub DivisionDocument16 pagesLack of Parental Supervision and Psychosocial Development of Children of School Going Age in Buea Sub DivisionEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Tha Significance of Early Childhood Adversity ArticleDocument2 pagesTha Significance of Early Childhood Adversity ArticleAriNo ratings yet

- Ang Naging Kamalayan Bunga NG Hiwalayan: Understanding Young Adults' Attitudes Towards Parental SeparationDocument22 pagesAng Naging Kamalayan Bunga NG Hiwalayan: Understanding Young Adults' Attitudes Towards Parental SeparationPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Disruptive Behavior, Developmental Delays, Anxiety, and Affective Symptomatology Among Institutionally Reared Romanian ChildrenDocument10 pagesPredictors of Disruptive Behavior, Developmental Delays, Anxiety, and Affective Symptomatology Among Institutionally Reared Romanian ChildrenAna AmaralNo ratings yet

- Issues On Human Growth and Development: Tiny Bea L. Tadeo Bsed Science IiDocument9 pagesIssues On Human Growth and Development: Tiny Bea L. Tadeo Bsed Science IiTiny Bea TadeoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7: Emotional and Behavioural Problems: DR Jessie EarleDocument28 pagesChapter 7: Emotional and Behavioural Problems: DR Jessie EarlejajmajNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Foster Care On Development: Development and Psychopathology February 2006Document21 pagesThe Impact of Foster Care On Development: Development and Psychopathology February 2006Salvador Richmae LacandaloNo ratings yet

- Child MaltreatmentDocument9 pagesChild MaltreatmentLeah Moyao-DonatoNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Parents of Children With Autism-LibreDocument47 pagesExperiences of Parents of Children With Autism-LibreBianca Serafincianu100% (1)

- Evidence Base For DIR 2020Document13 pagesEvidence Base For DIR 2020MP MartinsNo ratings yet

- Parent Child Attachment and Problem Behavior Reporting by Mothers With Pathology in Different Socioeconomic StatusDocument12 pagesParent Child Attachment and Problem Behavior Reporting by Mothers With Pathology in Different Socioeconomic StatusSudiptiNo ratings yet

- Prof Know Comp FinalDocument20 pagesProf Know Comp FinalLaine MarinNo ratings yet

- Prof Know Comp FinalDocument20 pagesProf Know Comp FinalJoanne Lei MuegoNo ratings yet

- DCP3MentalHealthCh 08-2Document18 pagesDCP3MentalHealthCh 08-2Isabella MuhadirNo ratings yet

- Smyke Et Al 2007Document9 pagesSmyke Et Al 2007Andreas KaunangNo ratings yet

- Pollack Et Al 2010 - Neurodevelopmental Effects of Early Deprivation in Post-Institutionalized ChildrenDocument19 pagesPollack Et Al 2010 - Neurodevelopmental Effects of Early Deprivation in Post-Institutionalized ChildrenHéc Tor NNo ratings yet

- Enlow 2012 - Interpersonal Trauma Exposure and Cognitive DevelopmentDocument7 pagesEnlow 2012 - Interpersonal Trauma Exposure and Cognitive DevelopmentRoxana AgafiteiNo ratings yet

- The Science of NeglectDocument20 pagesThe Science of NeglectdrdrtsaiNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Parents Towards Their Mentally Retarded Children A Rural Area Examination - N Govend PDFDocument101 pagesAttitudes of Parents Towards Their Mentally Retarded Children A Rural Area Examination - N Govend PDFUzmaShiraziNo ratings yet

- Brodzinsky, 2011, Children's Understanding of AdoptionDocument9 pagesBrodzinsky, 2011, Children's Understanding of AdoptioncristianNo ratings yet

- Thomas Et Al (2008)Document5 pagesThomas Et Al (2008)RebeccaNo ratings yet

- DCFS: Medical Lens IRRDocument6 pagesDCFS: Medical Lens IRRdiyaNo ratings yet

- Thesis 2.joan Edited - DocxxDocument45 pagesThesis 2.joan Edited - DocxxMary Joan AdlaonNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Behavior Disorders NotesDocument14 pagesDisruptive Behavior Disorders NotesAngela RegalaNo ratings yet

- Psychological and Developmental Effects of Single Parenting On The ChildDocument9 pagesPsychological and Developmental Effects of Single Parenting On The ChildIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Schonert-Reichletal ROESMHE2012Document22 pagesSchonert-Reichletal ROESMHE2012Sochsne CampbellNo ratings yet

- Children's Understanding of The Physical, Cognitive and Social Consequences of ImpairmentsDocument5 pagesChildren's Understanding of The Physical, Cognitive and Social Consequences of ImpairmentsAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Behavioural, Emotional and Social Development of Children Who StutterDocument10 pagesBehavioural, Emotional and Social Development of Children Who StutterMagaliNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal MathDocument5 pagesProject Proposal MathLorenz Philip AriasNo ratings yet

- Wiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentDocument38 pagesWiley Society For Research in Child Developmentcalmeida_31100% (1)

- Untitled DocumentDocument5 pagesUntitled Documentapi-384944871No ratings yet

- ASD Parent Stress Article 2004Document12 pagesASD Parent Stress Article 2004DhEg LieShh WowhNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Single Parenting in Socio Cultural - PHFC 8288Document8 pagesThe Impact of Single Parenting in Socio Cultural - PHFC 8288Pete DebbieNo ratings yet

- Emotion Knowledge in Young Neglected Children: Margaret W. SullivanDocument6 pagesEmotion Knowledge in Young Neglected Children: Margaret W. SullivanditeABCNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - 3 Quantitative ResearchDocument32 pagesChapter 1 - 3 Quantitative ResearchMichael Ron Dimaano83% (6)

- Self Stigma in ParentsDocument11 pagesSelf Stigma in ParentsLeticia Raquel Pe�a Pe�aNo ratings yet

- Meeting The Needs of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Early Intervention Experiences of Filipino ParentsDocument8 pagesMeeting The Needs of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Early Intervention Experiences of Filipino ParentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- 1st SourceDocument10 pages1st Sourceapi-581791742No ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- A National Profile of Childhood Epilepsy and Seizure DisorderDocument11 pagesA National Profile of Childhood Epilepsy and Seizure DisorderYovan FabianNo ratings yet

- KFP Final PaperDocument18 pagesKFP Final Paperapi-726319946No ratings yet

- The Construction of Fear Americans PrefeDocument19 pagesThe Construction of Fear Americans Prefeega meilindraNo ratings yet

- Developmental Issues For Young Children in Foster CareDocument8 pagesDevelopmental Issues For Young Children in Foster CarePedroPocasNo ratings yet

- PriveDocument16 pagesPriveayel crossNo ratings yet

- RD - Mental Health in Deaf Children (Data Kesehatan Mental Tunarungu)Document2 pagesRD - Mental Health in Deaf Children (Data Kesehatan Mental Tunarungu)dennyabdurrachman20No ratings yet

- Rodelas Melogen NDocument2 pagesRodelas Melogen NMelogenRodelasNo ratings yet

- Brainsci 08 00010 v2Document14 pagesBrainsci 08 00010 v2FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- s43045 023 00349 7Document19 pagess43045 023 00349 7FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- CAATDocument13 pagesCAATFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Saleh 2016Document11 pagesSaleh 2016FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Sheridan 2017Document18 pagesSheridan 2017Suzie Simone Mardones SilvaNo ratings yet

- NSteenkamp&IHendricksDocument52 pagesNSteenkamp&IHendricksFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Auoregula Et NeuroDocument5 pagesAuoregula Et NeuroFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Auoregula Et NeuroDocument5 pagesAuoregula Et NeuroFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Cool Versus Hot Executive Function PDFDocument4 pagesCool Versus Hot Executive Function PDFPoutsas GamiasNo ratings yet

- CTQ Chilfren?Document13 pagesCTQ Chilfren?FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Vitiello 2017Document9 pagesVitiello 2017FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Differences: Igor ArehDocument5 pagesPersonality and Individual Differences: Igor ArehFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- The Shape Trail Test Application of A New VariantDocument7 pagesThe Shape Trail Test Application of A New VariantFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- The Shape Trail Test Application of A New VariantDocument7 pagesThe Shape Trail Test Application of A New VariantFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology in An Ageing World: Ageism and Intergenerational Relations Sik Hung NGDocument18 pagesSocial Psychology in An Ageing World: Ageism and Intergenerational Relations Sik Hung NGFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Agneta, 2013Document33 pagesAgneta, 2013FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- Working in A Pandemic Work, Family, and Health OutcomesDocument12 pagesWorking in A Pandemic Work, Family, and Health Outcomespurple girlNo ratings yet

- 에티오피아 제약 의료기기 인허가 절차 소개 - 영문Document39 pages에티오피아 제약 의료기기 인허가 절차 소개 - 영문Kidist TesfayeNo ratings yet

- VermicompostDocument13 pagesVermicompostParomita Patra80% (5)

- Z-TRACK-METHOD ChecklistDocument5 pagesZ-TRACK-METHOD ChecklistDaniela Villanueva RosalNo ratings yet

- Lab Worksheet 1 Cranial NervesDocument6 pagesLab Worksheet 1 Cranial NervesDale P. PolvorosaNo ratings yet

- Received::::: Name Lab No. Gender: Collected Female Mrs. Shampa KarmakarDocument2 pagesReceived::::: Name Lab No. Gender: Collected Female Mrs. Shampa KarmakarakanshaNo ratings yet

- PHSA Brigada Sining Proposal To LBDocument10 pagesPHSA Brigada Sining Proposal To LBlaurenceNo ratings yet

- Housing Colorado in Conjunction With University of Colorado Denver College of Architecture and PlanningDocument7 pagesHousing Colorado in Conjunction With University of Colorado Denver College of Architecture and PlanningAmy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Health Safety and Nutrition For The Young Child 9th Edition Marotz Test BankDocument21 pagesHealth Safety and Nutrition For The Young Child 9th Edition Marotz Test BankJosephWilliamsinaom100% (13)

- Yeni Microsoft PowerPoint SunusuDocument9 pagesYeni Microsoft PowerPoint SunusuElif DoğanNo ratings yet

- Food Safety For Food Security Relationship Between Global Megatrends and Developments in Food SafetyDocument16 pagesFood Safety For Food Security Relationship Between Global Megatrends and Developments in Food SafetyWayne0% (1)

- Chapter Five Continuous Learning About MarketsDocument12 pagesChapter Five Continuous Learning About MarketsDr. Sahin SarkerNo ratings yet

- ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOUR - The InternDocument4 pagesORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOUR - The InternVandanaNo ratings yet

- What Are Knock Knees?Document2 pagesWhat Are Knock Knees?thet waiNo ratings yet

- G11 HOPE Module 6Document16 pagesG11 HOPE Module 6Unk NownNo ratings yet

- Case Study - HivDocument10 pagesCase Study - HivJoycee BurtanogNo ratings yet

- Día Transfer. Labarta 4. Pacientes Con P4 Tras Recuperación Con Progesterona SubuctáneaDocument8 pagesDía Transfer. Labarta 4. Pacientes Con P4 Tras Recuperación Con Progesterona SubuctáneaAnaNo ratings yet

- Health & Safety Risk Assessment FormMar20Document1 pageHealth & Safety Risk Assessment FormMar20Weei Zhee70No ratings yet

- Final Version MTP Poster 2022 2Document1 pageFinal Version MTP Poster 2022 2Hema Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Assessment Guide: CHCDIS007 Facilitate The Empowerment of People With DisabilityDocument31 pagesAssessment Guide: CHCDIS007 Facilitate The Empowerment of People With Disabilitydenis67% (3)

- Lesson 1 Nature of PsychologyDocument4 pagesLesson 1 Nature of PsychologyMariah A.No ratings yet

- Guideline Perkeni 2019Document29 pagesGuideline Perkeni 2019Tiens MonisaNo ratings yet

- Soal Bhs. Inggris - Lat Utbk 1Document6 pagesSoal Bhs. Inggris - Lat Utbk 1Elriska TiffaniNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Student Learning 1Document10 pagesAssessment of Student Learning 1Gerald TacderasNo ratings yet

- Activity Book - Greenman Level B - Unit 3Document6 pagesActivity Book - Greenman Level B - Unit 3Inglês na Europa com a Vivi MarquesNo ratings yet

- TPN CalculationDocument3 pagesTPN CalculationSARANYANo ratings yet

- 265579adjective Fill in The Blanks - Crwill - 230821 - 115353Document11 pages265579adjective Fill in The Blanks - Crwill - 230821 - 115353goluraviranjan84No ratings yet

- Erikson's Psycho-Social Theory of DevelopmentDocument10 pagesErikson's Psycho-Social Theory of DevelopmentCielo DasalNo ratings yet

- Errors During ExposureDocument39 pagesErrors During ExposureMostafa El GendyNo ratings yet

- Winnicott ch1 PDFDocument18 pagesWinnicott ch1 PDFAlsabila NcisNo ratings yet

- Internship ReportDocument39 pagesInternship ReportOdongo Isaac100% (4)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (403)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (20)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Summary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Secure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeFrom EverandSecure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (18)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossFrom EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- How to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingFrom EverandHow to ADHD: The Ultimate Guide and Strategies for Productivity and Well-BeingNo ratings yet