Professional Documents

Culture Documents

P 2

Uploaded by

touman100320 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesThis document discusses the educational philosophies of Plato and Herbart. It notes that Plato believed that society functions best when each individual is educated and working in areas that suit their natural aptitudes. This allows each person to contribute to the whole of society. The document then discusses Herbart's views on education, noting that he took education out of routine and focused on the interactions between new and old knowledge. Herbart believed the educator's role is to select appropriate material to shape initial reactions, then sequence subsequent material based on prior learning. This establishes control and order in the educational process.

Original Description:

Original Title

p2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the educational philosophies of Plato and Herbart. It notes that Plato believed that society functions best when each individual is educated and working in areas that suit their natural aptitudes. This allows each person to contribute to the whole of society. The document then discusses Herbart's views on education, noting that he took education out of routine and focused on the interactions between new and old knowledge. Herbart believed the educator's role is to select appropriate material to shape initial reactions, then sequence subsequent material based on prior learning. This establishes control and order in the educational process.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesP 2

Uploaded by

touman10032This document discusses the educational philosophies of Plato and Herbart. It notes that Plato believed that society functions best when each individual is educated and working in areas that suit their natural aptitudes. This allows each person to contribute to the whole of society. The document then discusses Herbart's views on education, noting that he took education out of routine and focused on the interactions between new and old knowledge. Herbart believed the educator's role is to select appropriate material to shape initial reactions, then sequence subsequent material based on prior learning. This establishes control and order in the educational process.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

intellectual opportunities are accessible to all on

equable and easy terms. A society marked off into

classes need he specially attentive only to the

education of its ruling elements. A society which is

mobile, which is full of channels for the

distribution of a change occurring anywhere,

must see to it that its members are educated to

personal initiative and adaptability. Otherwise,

they will be overwhelmed by the changes in

which they are caught and whose significance or

connections they do not perceive. The result will be

a confusion in which a few will appropriate to

themselves the results of the blind and externally

directed activities of others.

3. The Platonic Educational Philosophy.

Subsequent chapters will be devoted to making

explicit the implications of the democratic ideas in

education. In the remaining portions of this

chapter, we shall consider the educational

theories which have been evolved in three epochs

when the social import of education was

especially conspicuous. The first one to he

considered is that of Plato. No one could better

express than did he the fact that a society is stably

organized when each individual is doing that for

which he has aptitude by nature in such a way as to

be useful to others (or to contribute to the

whole to which he belongs); and that it is the

business of education to discover these aptitudes

and progressively to train them for social use.

assimilation of new presentations, their character is

all important. The effect of new presentations is to

reinforce groupings previously formed. The

business of the educator is, first, to select the

proper material in order to fix the nature of the

original reactions, and, secondly, to arrange the

sequence of subsequent presentations on the

basis of the store of ideas secured by prior

transactions. The control is from behind, from the

past. instead of, as in the unfolding conception, in the

ultimate goal.

(3) Certain formal steps of all method in

teaching may be laid down. Presentation of new

subject matter is obviously the central thing, but

since knowing consists in the way in which this

interacts with the contents already submerged

below consciousness, the first thing is the step of

"preparation,"-that is, calling into special activity

and getting above the floor of consciousness those

older presentations which are to assimilate the

new one. Then after the presentation, follow the

processes of interaction of new and old; then

comes the application of the newly formed

content to the performance of some task.

Everything must go through this course;

consequently there is a perfectly uniform method in

instruction in all subjects for all pupils of all ages.

Herbart's great service lay in taking the work of

teaching out of the region of routine and accident.

i/8 07:43 AM Chapter Seven: The...Education (12/30) 23.4%

control. To say that one knows what he is about, or

can intend certain consequences, is to say, of

course. that he can better anticipate what is going to

happen; that he can, therefore, get ready or

prepare in advance so as to secure beneficial

consequences and avert undesirable ones. A

genuinely educative experience, then, one in

which instruction is conveyed and ability

increased, is contradistinguished from a routine

activity on one hand, and a capricious activity on the

other. (a) In the latter one "does not care what

happens"; one just lets himself go and avoids

connecting the consequences of one's act (the

evidences of its connections with other things)

with the act. It is customary to frown upon such

aimless random activity, treating it as willful

mischief or carelessness or lawlessness. But there is

a tendency to seek the cause of such aimless

activities in the youth's own disposition, isolated

from everything else. But in fact such activity is

explosive, and due to maladjustment with

surroundings. Individuals act capriciously

whenever they act under external dictation, or

from being told, without having a purpose of their

own or perceiving the bearing of the deed upon

other acts. One may learn by doing something

which he does not understand; even in the most

intelligent action, we do much which we do not

mean, because the largest portion of the

connections of the act we consciously intend are not

perceived or anticipated. But we learn only

22.8%

u9

079. 07:40 AM

0737 AM Educa. Progressive(15/18)

Chapter Six: Educa...rogressive (3/1B) 21.3%

You might also like

- PoliticalDocument12 pagesPoliticalAshok ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Trivium and Quadrivium Cliff Notes by Gene OdeningDocument28 pagesTrivium and Quadrivium Cliff Notes by Gene Odening8thestate95% (21)

- Low Hanging SystemDocument69 pagesLow Hanging SystemVina100% (1)

- 14 - Chapter 3 TheoryDocument12 pages14 - Chapter 3 TheoryIza Fria MarinNo ratings yet

- Final Cep 800 Personal Theory of LearningDocument8 pagesFinal Cep 800 Personal Theory of Learningapi-509434120No ratings yet

- Secret Teachings of Critical ThinkingDocument13 pagesSecret Teachings of Critical ThinkingJohn M. Smith80% (5)

- 435 Solution 3Document7 pages435 Solution 3Shahin Oing0% (1)

- Kotak InsuraceDocument1 pageKotak InsuraceRemo RomeoNo ratings yet

- BELSONDRA - BT Retail Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesBELSONDRA - BT Retail Case AnalysisSim BelsondraNo ratings yet

- 30 Pages WordDocument10 pages30 Pages WordAni RajNo ratings yet

- 30 Images PDFDocument30 pages30 Images PDFamitava2010No ratings yet

- Images 30Document22 pagesImages 30Jair jrNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument30 pagesProjectbc230405476mchNo ratings yet

- 30 Images PDFDocument32 pages30 Images PDFhsiriyahhNo ratings yet

- TranslationDocument53 pagesTranslationMarjan MiticNo ratings yet

- Project 100 PageDocument50 pagesProject 100 Pagenadinahmed272No ratings yet

- BookDocument100 pagesBookhakdogNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Pragmatism in Education We Learn From Reflection On Experience."Document5 pagesPhilosophy of Pragmatism in Education We Learn From Reflection On Experience."Ceres B. LuzarragaNo ratings yet

- P 4Document3 pagesP 4touman10032No ratings yet

- PDF BookDocument44 pagesPDF Bookcafil71687No ratings yet

- 25 Page (96-120)Document12 pages25 Page (96-120)Krista BashyalNo ratings yet

- Adequate Interplay of Experiences The More Action Tends To Become Routine On The Part of The Class at A Disadvantages and CapriciousDocument5 pagesAdequate Interplay of Experiences The More Action Tends To Become Routine On The Part of The Class at A Disadvantages and CapriciousHanan KhanNo ratings yet

- ДокументDocument12 pagesДокументMarian 7180No ratings yet

- Project 1Document30 pagesProject 1Taqwa ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Final The Problem of Instruction Is Thus That of Finding Material Which Will Engage A Person in Specific Activities Having An Aim or Purpose of Moment or Interest To HimDocument73 pagesFinal The Problem of Instruction Is Thus That of Finding Material Which Will Engage A Person in Specific Activities Having An Aim or Purpose of Moment or Interest To HimCare PointNo ratings yet

- History ProjectDocument101 pagesHistory ProjecttimothymorgangeorgeNo ratings yet

- Nature of Freedom: Progressive Organization On The Subject MatterDocument18 pagesNature of Freedom: Progressive Organization On The Subject MatterFrances Angelie NacepoNo ratings yet

- P 11Document3 pagesP 11touman10032No ratings yet

- Nothing Less) Between The Wider Sphere ofDocument3 pagesNothing Less) Between The Wider Sphere oftouman10032No ratings yet

- Constructivist Learning TheoryDocument13 pagesConstructivist Learning TheoryJan Alan RosimoNo ratings yet

- Skinner, B. F. (1960) Modern Learning Theory and Some New Approaches To TeachingDocument10 pagesSkinner, B. F. (1960) Modern Learning Theory and Some New Approaches To TeachingLívia Fernandes BomfimNo ratings yet

- Learning To KnowDocument7 pagesLearning To KnowMa'am AnjNo ratings yet

- p6 (19 26Document170 pagesp6 (19 26Pilar Aguilar MalpartidaNo ratings yet

- Pilar EsDocument8 pagesPilar Esrodriguezlopezmarcelo24No ratings yet

- P 10Document3 pagesP 10touman10032No ratings yet

- Dewey CreedDocument53 pagesDewey CreedDominic Roman TringaliNo ratings yet

- Active LearningDocument4 pagesActive LearningNoevir Maganto MeriscoNo ratings yet

- Es of LearningDocument13 pagesEs of Learningjohnmer BaldoNo ratings yet

- What Is Educational PsychologyDocument4 pagesWhat Is Educational PsychologyRICKY SALABENo ratings yet

- Facing The Modern World by Giving Studentes Control of Their Own Education - MeirieuDocument9 pagesFacing The Modern World by Giving Studentes Control of Their Own Education - Meirieuioio1469No ratings yet

- Situated and Sociocultural TheoryDocument1 pageSituated and Sociocultural TheoryGeri-Ann TagalogNo ratings yet

- School As Slavery by Alex J TavarezDocument10 pagesSchool As Slavery by Alex J TavarezaljavarezNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Development of Children and AdolescentsDocument23 pagesCognitive Development of Children and AdolescentsHaezil MioleNo ratings yet

- Foucault's PrisonDocument2 pagesFoucault's PrisonChetan ChitreNo ratings yet

- The 4 Pillars of EducationDocument13 pagesThe 4 Pillars of EducationSharifah Athirah Wan Abu Bakar100% (1)

- Situated LearningDocument5 pagesSituated LearningEn-En Caday Tindugan BautistaNo ratings yet

- Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of A ConceptDocument16 pagesCommunities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of A ConceptthebeekeeperNo ratings yet

- Pragmatism: Education As A Social InstitutionDocument5 pagesPragmatism: Education As A Social InstitutionKristine Santiago AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Developmental and Soci Cultural Dimensions of LearningDocument23 pagesDevelopmental and Soci Cultural Dimensions of LearningLea Lian Aquino AbejeroNo ratings yet

- The Four Pillars of EducationDocument21 pagesThe Four Pillars of Educationsyahirah mahatNo ratings yet

- Transcript (Confident Learner)Document7 pagesTranscript (Confident Learner)dorklee9080No ratings yet

- Compilation of TheoriesDocument15 pagesCompilation of TheoriesQuenie De la Cruz100% (1)

- Nonformal Learning and Tacit Knowledge in Professional Work - AfraDocument24 pagesNonformal Learning and Tacit Knowledge in Professional Work - Afrairfan ardiNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Behavioral Learning TheoryDocument3 pagesCritical Analysis of Behavioral Learning Theoryantonio jr doblonNo ratings yet

- Дополнительные Материалы К Учебнику Mcmillan Destinations C1-C2. Unit 2. Thinking And LearningDocument19 pagesДополнительные Материалы К Учебнику Mcmillan Destinations C1-C2. Unit 2. Thinking And LearningKIRILLNo ratings yet

- Definition of Eductaion Unit 1.1 F.edDocument16 pagesDefinition of Eductaion Unit 1.1 F.edArshad Baig MughalNo ratings yet

- My Report Lesson 6Document3 pagesMy Report Lesson 6Drew MerezNo ratings yet

- Perception ActivityDocument2 pagesPerception ActivityDragos-Cristian FinaruNo ratings yet

- The Nature of AimDocument51 pagesThe Nature of AimSajid KhanNo ratings yet

- Msoe 1 em PDFDocument10 pagesMsoe 1 em PDFFirdosh KhanNo ratings yet

- Learned Helplessness, As A Technical Term inDocument5 pagesLearned Helplessness, As A Technical Term inKiervin Paul NietesNo ratings yet

- What Are The Principles of Constructivism?: Knowledge Is Constructed, Rather Than Innate, or Passively AbsorbedDocument5 pagesWhat Are The Principles of Constructivism?: Knowledge Is Constructed, Rather Than Innate, or Passively Absorbedsidra iqbalNo ratings yet

- P 10Document3 pagesP 10touman10032No ratings yet

- OrganizeDocument3 pagesOrganizetouman10032No ratings yet

- Nothing Less) Between The Wider Sphere ofDocument3 pagesNothing Less) Between The Wider Sphere oftouman10032No ratings yet

- F "Social" As A Function and Test ofDocument3 pagesF "Social" As A Function and Test oftouman10032No ratings yet

- Creation of Israel, 1948 - Milestones - 1945-1952 - Milestones in The History ofDocument2 pagesCreation of Israel, 1948 - Milestones - 1945-1952 - Milestones in The History ofAhsanaliNo ratings yet

- Akbar ArchiectureDocument52 pagesAkbar ArchiectureshaazNo ratings yet

- Module 8 TQMDocument19 pagesModule 8 TQMjein_amNo ratings yet

- Evidence NotesDocument4 pagesEvidence NotesAdv Sheetal SaylekarNo ratings yet

- Coke CaseDocument1 pageCoke Caserahul_madhyaniNo ratings yet

- The Goddess Within and Beyond The Three PDFDocument417 pagesThe Goddess Within and Beyond The Three PDFEkaterina Aristova100% (4)

- 23 PDFDocument14 pages23 PDFNational LifeismNo ratings yet

- Jaime U. Gosiaco, vs. Leticia Ching and Edwin CastaDocument33 pagesJaime U. Gosiaco, vs. Leticia Ching and Edwin CastaClaudia Rina LapazNo ratings yet

- 00 - Indicadores para Certificado Sostenible BREEAM-NL para Evaluar Mejor Los Edificios Circulares-51Document1 page00 - Indicadores para Certificado Sostenible BREEAM-NL para Evaluar Mejor Los Edificios Circulares-51primousesNo ratings yet

- (Even in A Recession!) : Create An Irresistible Offer That SellsDocument17 pages(Even in A Recession!) : Create An Irresistible Offer That Sellsfreaka77No ratings yet

- Resume ShakinaDocument2 pagesResume ShakinaSiti ShkinnNo ratings yet

- Proceedings-Vol 09 No 07-July-Aug-Sept-1971 (George Van Tassel)Document16 pagesProceedings-Vol 09 No 07-July-Aug-Sept-1971 (George Van Tassel)Homers Simpson100% (3)

- UntitledDocument44 pagesUntitledAfnainNo ratings yet

- A Grammar of Mandarin Chinese Lincom Europa PDFDocument208 pagesA Grammar of Mandarin Chinese Lincom Europa PDFPhuong100% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Strong Wings: Deep RootsDocument252 pagesStrong Wings: Deep RootsBelina ZhangNo ratings yet

- Ana Pagano Health in Black and WhiteDocument24 pagesAna Pagano Health in Black and WhiteTarcisia EmanuelaNo ratings yet

- The Great Leap ForwardDocument30 pagesThe Great Leap ForwardBò SữaNo ratings yet

- Journeyto India by Joni Patry BWDocument7 pagesJourneyto India by Joni Patry BWVigneshwaran MuruganNo ratings yet

- Andrew Wommack Live Bible StudyDocument4 pagesAndrew Wommack Live Bible StudyNathanVargheseNo ratings yet

- Study Material For The Students of B. A. Prog. II Year SEC-Translation StudiesDocument5 pagesStudy Material For The Students of B. A. Prog. II Year SEC-Translation StudiesAyshathul HasbiyaNo ratings yet

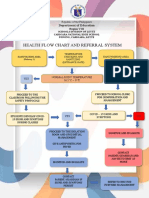

- Health Flow Chart and Referral System: Department of EducationDocument2 pagesHealth Flow Chart and Referral System: Department of EducationWendy TablaNo ratings yet

- Nego Bar QuestionsDocument9 pagesNego Bar QuestionsJem Madriaga0% (1)

- Approved JudgmentDocument42 pagesApproved JudgmentANDRAS Mihaly AlmasanNo ratings yet

- HW No. 2 - Victoria Planters Vs Victoria MillingDocument2 pagesHW No. 2 - Victoria Planters Vs Victoria MillingAilyn AñanoNo ratings yet

- Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 228 / Tuesday, November 28, 2006 / NoticesDocument6 pagesFederal Register / Vol. 71, No. 228 / Tuesday, November 28, 2006 / NoticesJustia.com0% (1)