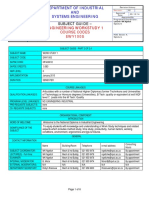

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Zeitlin Solomon) 1947

Uploaded by

Willy K. Ng'etichOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(Zeitlin Solomon) 1947

Uploaded by

Willy K. Ng'etichCopyright:

Available Formats

Jewish Rights in Palestine

Author(s): Solomon Zeitlin

Source: The Jewish Quarterly Review , Oct., 1947, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Oct., 1947), pp. 119-134

Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1453037

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Jewish Quarterly Review

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE

By SOLOMON ZEITLIN, Dropsie College

THE critical position that Palestine occupies in the peace

of the Near East - possibly in the peace of the world

has turned the eyes of mankind towards that strife-ridden,

harassed, little land. The United Nations, through its

appointment of an investigating commission, has manifested

this universal concern over the fate and destiny of Pal-

estine.

In this essay our aim is to clarify on the basis of authentic

original sources what rights inhere in the Palestine situa-

tion for the Jews and other peoples from the standpoint

of religion, history, and law. Partisan literature on Pal-

estine has tended to confuse fundamental basic issues.

Extravagant claims and counter-claims are but poor count-

erfeit substitutes for the realities of history. At this crucial

historic moment, when the fate of Palestine is about to

be weighed in the councils of the United Nations, we pro-

pose to review the sources to be found in Jewish, Christian,

and Mohammedan literature which throw light upon the

religious, historic, and legal claims to Palestine.

1. RELIGIOUS CLAIMS

Palestine, as the land of Israel, has been religiously con-

nected with the Jews from their beginnings down to modern

days. In the Pentateuch God promised the patriarchs in

a covenant that their children would inherit this land pro-

vided they in return would accept Him as their God. The

God of Israel was regarded as the God of the land.

According to the prophets the Israelites were exiled

119

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

120 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

from their land because they did not worship the God of

the land. Ezekiel in his vivid and memorable vision com-

pared the Israelites who had given up hope of ever return-

ing to the homeland to "dry bones." "Our bones are

dried up," they cried, "and our hope is lost; we are clean

cut off." But the prophet, to encourage them and to inject

new life in their "dried bones," in the name of God replied:

"I will put My spirit in you and ye shall live and I will

place you in your own land."',

After the return to the homeland, the people no longer

considered God to be connected with the land of Israel

only; He is the God of the universe.2 However, the land

of Israel remained the holy land for all the Jews of the

world. Jerusalem was the mother city, the Holy City, for

all the Jews; and it was so named by Philo.3 Josephus like-

wise called Jerusalem the Holy City,4 for it is the mother

city of all the Jews of the inhabitable globe.

During the time of the Second Commonwealth the Jews

of the entire Diaspora made pilgrimages to the Holy Land,

and sent sacrifices to the Temple. These pilgrimages never

ceased throughout the history of the Jewish people. The

ancient rabbis spoke of the Jews living there as assured

of a portion in the future world.5 According to them, the

precept to settle in Palestine was equal to the sum total

of all the other precepts of the Torah.6 Even a breach in

the observance of the strict laws of the Sabbath was some-

times overlooked, when it was done in the interest of ac-

quiring property in Palestine.7 Throughout the Middle

Ages the Jews and the land continued an integrated entity.

IEz. 37.

2 See my study, "Judaism as a Religion," JQR, 1943, pp. 327-43.

3 Legatio ad Gaium, 36.

4Jewish War, II, 16, 4, (397); VII, 8, 7 (379).

s Yer. Shek. 3, 3. min N.n Y low n *... *Mv y-ix 'Diwp' '.

6 Ket. 110b. riinrwv nixvn i: -i= nlipv xnmw r-im n:riz, i-mm.

7 B. K. 80b. new: im 1ims i' pby innl:) i ryix n'm nprim .

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 121

Judah ha-Levi, the celebrated poet and philosopher of

the 12th century, voiced the belief that God had selected

Israel as the Chosen People. He also selected Palestine

of all the countries of the earth as His favorite abode.

True, God was the Creator and Master of the entire universe

but the land of Israel was especially dedicated to Him.

While other countries were ruled by angels, God Himself

ruled the land of Israel, which He gave as an inheritance

to His people. The divine election of Israel was interwoven

with the selection of the land. Only through the land of

Israel, it was believed, could the Jews advance to per-

fection.8

Judah ha-Levi's passionate love for Palestine, so glow-

ingly revealed in his elegaic poems, immortalized his

peoples' love and longing for the Holy Land. His heart was

in the East even though his body was in the West. He left

his home for his beloved Palestine, braving the dangers and

hazards of the journey. A legend relates that when he

entered Jerusalem an Arab came galloping along and trod

him down. He died kissing the soil of Jerusalem, and the

last word he uttered was his Song of Zion.

Nachmanides, who was born shortly after the Latin

kingdom was destroyed by Saladin and who witnessed the

conquest of Palestine by the Mamelukes, said that since

the Jews left Palestine, no nation could or would hold Pal-

estine. The land belongs to the children of Israel. It was

the particular domain of God.9

This conception became a part of Jewish theology. Ac-

cording to the rabbis, only in Palestine could a prophet

arise, for only there could the Holy Spirit be found.

Of the three universal religions, Judaism, Christianity

and Islam, only Judaism is continuously interwoven with

8 Comp. Kuzari, II, 11-24.

9 Comp. Nabmanides, Lev. 18.25.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

122 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

Palestine. The Christians did not consider Judaea, now

known as Palestine, of any great importance in connection

with their religion. When Jerusalem was besieged by the

Romans the Christians did not defend the city, as did

their Jewish brethren, but left for Pella.Io For them Judaea

was not a Holy Land. Only the places of Jesus's birth and

burial were considered loca sancta."l For the Jews, however,

the entire country of Palestine was considered a Holy Land.

Other cities and places were regarded as holy in the eyes

of the Christians. Indeed, St. Jerome wrote in one of his

letters: "The court of heaven is equally open from Jeru-

salem and Britain.9 12

Eusebius, The Church History, IV, 5.

"1 The earth where Jesus was buried was considered holy and was

used as a means of exorcism of evil spirits. Acceperat autem ab amico

suo terram sanctam de Hierosolymis adlatam, ubi sepultus Christus die

tertio resurrexit. "Now he (Hesperius) had received from a friend of

his own some holy earth brought from Jerusalem, where Christ, having

been buried, rose again the third day." De Civitate Dei, XXII, 8. In

the early centuries of Christianity devout Christians used to go to

Jerusalem to visit the holy places. We are told that Arculfus, a bishop

of Gaul, went to Jerusalem for the sake of the holy places.

The first to call Palestine the Holy Land, Terra Sancta, was Pope

Urban 11, who, in addressing the Council of Clermont (in the year

1095), said: "Quam terram merito Sanctam diximus, in qua non est etiam

passus pedis quem non illustraverit et sanctificaverit vel corpus vel umbra

Salvatoris, vel gloriosa praesentia Sanctae Dei genitricis, vel amplectendus

Apostolorum commeatus, vel martyrum ebibendus sanguis effusus. The

name, Holy Land, applied to Palestine, thus was for the first time

emphasized by Pope Urban II and has been frequently used down to

our own time. However, neither in the New Testament nor in the

writings of the Church Fathers, was the term Holy Land ever applied

to Palestine.

12 et de Hierosolymis et de Britannia aequaliter patet aula caelestis;

... Antonius et cuncta Aegypti et Mesopotamiae, Ponti, Cappadociae

et Armeniae examina monachorum non uidere Hierosolyman, et patet

illis absque hac urbe paradisi ianua. beatus Hilarion, cum Palaestinus

esset, in Palaestina uiueret, uno tantum die uidit Hierosolymam, ut nec

contemneret sancta loca propter uiciniam nec rursus deum loco cludere

uideretur.

"Anthony, and all the swarms of monks of Egypt and Mesopotamia,

of Pontus, Cappadocia, and Armenia, saw not Jerusalem; and the gate

of Paradise is open to them without (a knowledge of) this city. The

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 123

Christianity, in truth, arose in Jerusalem; but the early

Christians gave up the earthly Jerusalem and spoke only

of the Heavenly Jerusalem. "But Jerusalem which is above

is free, which is the mother of us all,"I3 wrote Paul to the

Galatians. St. Augustine also spoke of a heavenly Jeru-

salem but not of the Jerusalem on earth. For him the true

Jerusalem, the eternal one, was in heaven, "Whose children

are all those who live according to God on the earth."I4

Judaism, on the other hand, while also speaking of a heavenly

Jerusalem always emphasized the earthly Jerusalem. The

heavenly Jerusalem, moreover, could only be realized after

the earthly Jerusalem has been re-established. This is well

expressed in the Talmud. God said: "I will not enter the

heavenly Jerusalem until I reenter the earthly Jerusalem."I's

Rome, the city where Peter and Paul were executed,

became the center of Christianity and its symbol. For

the Christians Rome became the Eternal City. James

Bryce well characterized this fact when he said: "To be

a Roman was to be a Christian, and this idea soon passed

into the converse. To be a Christian was to be a Roman."'6

Judaism, on the other hand, recognized no holy places

outside Palestine. The Jews who lived in the Diaspora

were always connected spiritually with the Holy Land.

They never ceased to pray for the coming of the Messiah,

when Palestine would be the center of the religion of the

entire world, when the prophecy of Isaiah about the uni-

blessed Hilarion, though he was a native of Palestine, and lived in

Palestine, only saw Jerusalem on a single day; that he might not appear

to despise the holy places on account of their nearness, nor, on the

other hand, to confine God to place." Epistula, LVIII, 3. Comp. also

CVIII.

I134.26.

I Id est ueram Hierusalem aeternam in caelis, cuius filii homines sec-

undum Deum uiuentes peregrinantur in terris. De civitate Dei, XVII, 3.

IS Tan. 5a. wta -y rlon m'iw 1?z mam mt? mp -,Pn 1mnl' ', -,o

i6 The Holy Roman Empire, chs. 5-9.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

124 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

versal fellowship of man would be fulfilled. In a word,

in Christianity only those places connected with Jesus's

birth, his sojournings and the holy sepulcher were par-

ticularly sacred, not Palestine as a whole. For Judaism

Palestine is central to the most important aspects of Jewish

theology.

As to Islam, Palestine can hardly be said to have played

an important part in Islamic thought. While the roots of

Christianity stem from Palestine, Islam flowered in the

desert of Arabia. The Koran does not make mention of

Palestine; its religion is focused on Mecca.16a It is true

that the Koran (Sura 17) relates that Mohammed was

transported at night from the sacred Temple of Mecca to

the Temple of Jerusalem, and, according to tradition, was

carried through the seven heavens to the presence of God

and was brought back to Mecca the same night. But,

apart from this, Palestine never became an integral part

of the religion of Islam.

Mohammed, in order to break with Judaism and Chris-

tianity, particularly the former, substituted Friday for

the Sabbath; Ramadan was established as a month of

i6a In Koran, Sura 21, Mohammed is reported as saying: "We

delivered him (Abraham) and Lot by bringing them into the land

wherein we have blest all creatures." According to some commentators,

this land is Palestine. Baidawi, however, takes the meaning to be that

God brought Abraham and Lot from Iraq to Syria, }.11 {_. ,$1

lt.J1 53l.

Again, in Koran, Sura 5, Moses implores the Jews to "enter the Holy

Land (4.38 Ai2l ) which God hath decreed you." Here, too, most

commentators refer the expression to Palestine. Baid.awi, however

records an opinion that it denotes the Mountain (of Sinai) and its

environs. "There is an opinion that it means the Mountain (Sinai)

and its surroundings." (Baidawi 5.24) In any event, Palestine did not

figure to any appreciable extent as a Holy Land in Islamic thought and

was not so considered by the True Believers, whereas to the Jews it

always possessed a sacred character. The author of II Maccabees,

which dates as early as c. 125 B. C. E., (Chapter 1, 7) designates

Palestine as a"ya 'y (Holy Land).

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 125

fasting; and qiblah -the direction to be observed during

prayers - even was changed from Jerusalem to Mecca. Pil-

grimage likewise was directed to Mecca, which was made

a holy city instead of Jerusalem.

From time to time the Moslems do go on pilgrimages

to such places as the Temple area, Hebron and the Nebi

Muisa, but these are only places of local pilgrimages. The

Koran commanded all believers to make pilgrimages to

Mecca (Sura 3). There is a tradition that if a Moslem

has not made at least one pilgrimage to Mecca he might

just as well have died a Jew or a Christian. On the other

hand, according to Jewish tradition, any Jew who lives

in Palestine is assured of a part in the future world.

To summarize: there are places in Palestine which be-

came holy to Christianity and to Islam, but the land as

a whole was not considered holy by these two religions.

Palestine as a Holy Land is connected with Judaism only.

2. HISTORICAL CLAIMS

One may argue that while it is true that Palestine is

considered the Holy Land for the Jews, historically it is

not their land since they lived there but a short time and

legally they lost title to it, when Palestine was conquered

by the Romans. What are the historical facts? The follow-

ing is a brief resume.

The land of Canaan, later known as Judaea and Palestine,

was conquered by the Hebrews under the leadership of

Joshua approximately two thousand years befQre the pres-

ent era. In the early days, there was no union among the

Hebrews: they were divided into tribes. They were subju-

gated for a time by different neighboring nations. Subse-

quently, some of the tribes united. The first real union

among the Jews came about when Saul was elected king.

This was some time at the end of the second millennium

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

126 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

before the Common Era. After him David ruled over all

Israel, and was succeeded by his son, Solomon. On Solo-

mon's death the United Kingdom was divided.

The Northern Kingdom was conquered by the Assyrians

and later, in 587-6 B. C. E., Judaea was captured by the

Babylonians. Not all the Jews, however, were exiled from

the land. According to the II Book of Kings the poorest

people were left in Judaea. In 538 B. C. E., Cyrus, the

king of Persia, gave the Jews permission to return to their

homeland. The Temple was rebuilt later, and the Jews

were settled in a free, autonomous land under the leadership

of their High Priests. Thus the Jews were in exile less

than fifty years, and even during that time some Jews,

the poorest among them, remained in Palestine to farm

the land.

In the year 333 B. C. E. Alexander defeated Darius and

became ruler of the Persian Empire, including Palestine

which was then called lower Syria (Coelo-Syria). With

the conquest of Judaea by Alexander, the status of the

land was not changed. The Jews, ruled by their High

Priests, remained there. After the death of Alexander the

land became a part of the Ptolemian empire and later a

part of the Seleucidean empire but the Jews continued

to live in Palestine uninterruptedly. Before Judaea became

an independent state, Judas Maccabeus made a political

alliance with the Romans.17

Pompey, the Roman general, captured Jerusalem in the

year 63 B. C. E. With the conquest of Judaea by Pompey,

changes occurred in the political life of the Jews but no

change took place in their religious life. Even later when

Judaea became a province of Rome, the Jews enjoyed a

measure of autonomy in their land. It was still consid-

ered the land of the Jews.

17 See I Mac. 8.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 127

In 70 C. E. Vespasian conquered Judaea and put an

end to its political independence. But the Jews were not

exiled from the land. The Romans punished only those

who participated in the revolt against them. The Jews

continued to live in the land under the autonomy of their

religious Sanhedrin.

After the revolt against Hadrian (132-135 C. E.), the

Jews were forbidden to enter Jerusalem but they were

allowed to live in Galilee. The center of Jewish life was

shifted from the South to the North, Tiberius becoming

the main seat of Jewish learning and the residence of the

Sanhedrin.

In the Fourth Century, when the Roman Empire was

divided, Palestine became a part of the Eastern Roman

Empire, Byzantium. Although the Jews were greatly hu-

miliated and persecuted and their religion only tolerated,

they continued to live in the land. In the year 615 Khusraw,

King of Persia, aided by the Jews, conquered Jerusalem.

In 628 the Byzantine king Heraclius reconquered Palestine.

A few years later (636 C. E.), the Arabs, sweeping in from

the desert with great fanaticism, holding the sword in one

hand and the Book in the other, put an end to the domi-

nance of the Byzantian Empire over Syria and Palestine.

The Eastern Roman Empire was eliminated from the Middle

East. It is told that when the city of Jerusalem surrendered

to the followers of Mohammed a condition was laid down

that no Jew should be allowed to remain in Jerusalem.

However, this agreement was not honored by Omar. We

know that the Jews not only were not disturbed in Palestine,

but a community was organized and flourished in Jerusalem.

Omar, the conqueror of Palestine, was succeeded by

Abu-Bakr. Later Ali became caliph. After the assassina-

tion of Ali, Mu' Awiyah was proclaimed caliph in lliya'

(Jerusalem) in the year 661, and Damascus became the

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

128 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

capital. With Mu' Awiyah the dynasty of the Omayyad cal-

iphate began and lasted to the year 750. This dynasty was

opposed by the 'Abbasids, descendants of an uncle of

Mohammed. In 750 Abu-al-'Abbas declared himself caliph

and established his capital in Bagdad. The families of these

two dynasties, the Omayyads and the 'Abbasids were not

Palestinian Arabs, but came. from South Arabia. In 969

the Fatimids (Shiites from Northern Africa) conquered

Egypt and soon afterwards Palestine, but about a century

thereafter, the Saljuiq Turks captured Jerusalem and re-

stored it to the 'Abbasid caliphs. In 1098 the Fatamids

again reconquered Palestine.'8

In the year 1096 the First Crusade was organized to

march on Palestine to retake the holy places from the

Moslems. In 1099 Jerusalem fell before the Crusaders.

The capture of Jerusalem by the Christians was celebrated

by savage butchery of Jews and Moslems alike. For a

while Jerusalem became the center of the Latin Kingdom.

Saladin, in the year 1187, defeated the Crusaders near

Hittin (Lower Galilee) and recaptured Jerusalem, thus

ending the Latin Kingdom. The last hold of Christianity

in the extreme North of Palestine was destroyed by the

Egyptian Mamelukes in the year 1291.

The Mamelukes were a dynasty of slaves of different

races and nationalities who absorbed the power in Egypt.

The word "Mameluke" bears the meaning of slave. For

more than two centuries the Mamelukes ruled Palestine.

Their hold over Palestine came to an end with the advance

of the Osman Turks. In 1517 Selim I captured Jerusalem

and brought Palestine under the empire of the Turks. The

Turks ruled Palestine until October 1917 when General

Allenby captured Jerusalem and brought their domination

to an end.

is See P. Hitti, History of the Arabs, London, 1937.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 129

The point of this brief survey of the changing rulers of

Palestine is to indicate that the Jews never left Pal-

estine. For almost a thousand years they had their own

rule-they ruled Palestine. Even after the Jewish state

was destroyed the Jews remained in Palestine, even if at

times their numbers were not great. There was no period

when there were no Jews in Palestine, and however humble

Palestine Jewry may have been at times, the Jews of the

world looked forward to the day when Elijah would blow

the trumpet to herald the coming of the Messiah and the

return of the Jews to Palestine.

The Palestinian Arabs or the Arabs of Trans-Jordania

never ruled Palestine. Palestine had been conquered by the

Arabs who came from the South. As stated above, the

dynasties of the Omayyads and the 'Abbasids were not

natives of Palestine. Certainly the Mamelukes and later

the Turks not only were not Palestinian Arabs, but were

of an entirely different race; they were not even Semitic.

Thus the historical claim of the Jews to Palestine is

not a fallacy, as Ibn Saud maintained in his recent letter

to the late President Roosevelt; they are based on unchal-

lengable historical facts.

Equally unfounded are Ibn Saud's claims to Palestine

as an Arabic country in the same letter: "The Arabs were

the first inhabitants and they dwelt there for a period of

3,500 years before Christ and have remained there since

Christ until the present day. They ruled it alone or with

the Turks for a period of about 1,300 years, whereas the

disjointed reign of the Jews did not exceed 380 confused

and sporadic years." That this is a fantastic claim has

been clearly indicated.

Palestine up to 734 C. E. was never an Arabic country

and was never so considered by geographers and historians.

Josephus as well as the Roman geographer Strabo placed

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

130 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

Arabia beyond the boundaries of Palestine, or as it was

then called, Judaea. On the other hand, the Jews held

sovereignty in the country not for "380 confused and

sporadic years," but from about 1028 B. C. E. until the

year 70 C. E. when Jerusalem fell before the Romans.

And even after the fall of Jerusalem the Jews in Palestine

as we indicated were ruled by their own patriarchs and

the Sanhedrin. Furthermore, as we shall soon point out,

when Palestine became a province of the Roman Empire,

the Jews were considered an associate people.

3. LEGAL RIGHTS

One may say, of course, that Judaism is the only religion

rooted in Palestine and that the Jews have a historical

claim on Palestine. But can one say they have a legal

claim since the country was captured by the Romans?

Did not the title to the country pass from the Romans

to the later conquerors?

When Titus captured Jerusalem in the year 70 C. E.

neither he nor his father Vespasian appended the title

Judaicus to their title of Emperor as was the custom of

Roman victors when they conquered a country.'9 The

reason why Vespasian did not append the title Judaicus

was two-fold. First, Judaism at that time was considered

a religion, and he could hardly adopt the title Judaicus.20

Secondly, Vespasian did not append the title Judaicus

because he did not annex Judaea to the Roman Empire.

Josephus said that the Emperor took Judaea for himself

as a private possession.2, The special tax (fiscus Judaicus)

19 Dio Cassius, 65 Kaf f r' caoroo To /UEJ TOV avTOKpaTOpOS 6ovo,a

apq6mrepot fXaI3oo ro be bi -rot) 'IovacuKov oi'vL5rEpos eaxe.

20 See S. Zeitlin, JQR XXXIV, 2 (1943).

2IJewish War, 7. 6,6 (217), "receiving the country as his private

property ov0 P'yap KaTq,KLOaE' &KEL 7ro6Xu' i6Lwa avT3c Tr?' Xwpac

JWXaTTrW 0 6KraKoUIoLs b6e' ,'6OU a6ro -rfs orpadtas aLaeLque'VoLS

xWpLOJ' 'WKEV EIS Ka-To'K?70L' 6 KaXeZTUa ,s'p 'A,u,uaovs ar'xet 8

TrW 'IEpoLoXv4uWv cTaaLous TprPcKOvTa.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 131

that Vespasian levied on the Jews after the War, was levied

not only on the Jews of Judaea, but on all the Jews of

the Empire, even on the proselytes.21a This religious tax

demonstrated the victory of Jupiter over the God of Israel.

Vespasian as the representative of Jupiter on earth,

appropriated the land for himself.

From the Roman historian Tacitus we learn that Titus

insisted that the Temple should be burned as a prime ne-

cessity "in order to wipe out more completely the religion

of the Jews and the Christians." He held, that "these re-

ligions, although hostile to each other, nevertheless sprung

from the same source. The Christians had grown out of

the Jews. If the root were destroyed the stock would

easily perish."22 Thus by the destruction of the Temple,

the Romans hoped to destroy the Jewish and Christian

religions.

The Jews continuing to live in Judaea were not con-

sidered as peregrini dediticii, that is, aliens whose country

had been destroyed and who now had no country. Thus,

when Emperor Caracalla conferred the Roman civitas (cit-

izenship)23 on all aliens, excepting only the peregrini dediticii

who had no country which they could claim as their home,

the Jews were among those who received Roman citizen-

ship. They were even called Romans24 and enjoyed all

the privileges and rights in their land, Palestine. The Jews

lived under their own administration, under an ethnarch,

the head of the Jewish community in Judaea. The Church

Father Origen, who lived in the third century and who

2.a Dio, Epitome LXV; Suetonius, Domitian XII.

22 At contra alii et Titus ipse evertendum in primis templum censebant

quo plenius iudaeorum et Christianorum religio tolleretur: quippe has

religiones, licet contrarias sibi, isdem tamen ab auctoribus profectas; Chris-

tianos ex Iudaeis extilisse: radice sublata stirpen facile perituram. (Frag-

ments of the Histories).

23 Lex Antoniona de civitate.

24 Iudaei Romano. Cod. Theod. II, 1, 8 (398).

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

132 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

spent some time in Judaea, observed that the Jews had

their own ethnarch and their own courts.

That the Jews were not considered a conquered people

but rather socii populi Romani, an associate people of the

Romans, can be inferred also from the fact that they had

the privilege of accepting public offices in the Roman gov-

ernment or declining them. This privilege which the Jews

enjoyed, was even incorporated in the Roman law as late

as 321 C. E.,25 a privilege which could not have been enjoyed

by a people who had no country.

That the Jews were an associate people of the Romans

can be also learned from their participation with the Ro-

mans in the war against Persia. When Sapor was victorious

over the Romans and conquered many cities in Judaea,

among them Caesarea, thousands of Jews were killed in

this war; they were killed as Romans. On the arrival of

this news to the Jews of Babylonia, Samuel, (the spiritual

head of Babylonian Jewry), did not tear his garments as

a sign of mourning.26 Since he was a Persian patriot, he

considered the killing of these Jews not as a specific Jewish

catastrophe; they were killed as participants with the

Romans in the war against Persia. The Talmud relates

that King Sapor prided himself on the fact that he never

killed a Jew.27 Apparently, he did not consider the thousands

of Jews killed in Caesarea as Jews; for him they were Ro-

mans.

That the Jews did not lose title to Palestine can further-

more be attested by historical and legal facts. The Jews

continued to exercise the right of owning slaves as well

25 Cunctis ordinibus general lege concedimus Iudaeos vocari ad curiam.

Verum ut aliquid ipsis ad solacium pristinae observationis relinquatur,

binos vel ternos privilegio perpeti patimur nullis nominationibus occupari.

Ibid. 16, 8, 3.

26 M. K. 26a nvrvn 'Iti1-n' '9i'?-n pw "$ rm k P

27H1 6iyp.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JEWISH RIGHTS IN PALESTINE-ZEITLIN 133

as the right of manumission,28 which peregrini dediticii did

not have.29 As late as the year 429 the Palestinian Sanhedrin

was still recognized in the Eastern Roman Empire.30 The

authority of the Jewish patriarchs was likewise acknowl-

edged.31 Clearly the Jews enjoyed citizenship, and were

not aliens in their own land.

According to international law, if a power conquers a

country, the title of the country passes from the vanquished

government to the conqueror, either by treaty or even with-

out treaty. If a country, however, was previously con-

quered and its conqueror was afterwards defeated by an-

other power, the later conqueror acquires title to all the

rights and privileges held by the previous government.

Though the Romans conquered Palestine, they did not

annex it to the Empire. When the Persians and later the

Arabs conquered Palestine from the Romans, they occupied

28 According to the Roman law only citizens had the right to own

slaves and the right to manumit them.

According to Eusebius the Emperor Constantine passed a law to

the effect that no Christian should be a slave to a Jewish master on

the ground that it would not be right that those whom Christ had ran-

somed should be subjected in slavery to a Jew. (The Life of Constantine,

IV, 27). Constantine, in passing this law that a Jew could not have

slaves who were Christians, specified the religious reason, but not the

legal. If the Jews were not citizens, the Emperor would have emphasized

the fact that aliens had no right to own slaves.

29 Manumissio vindicata, is a form of manumission by means of in

jure cessio. Peregrinus cannot acquire property by mancipatio. Per-

egrinus, however, enjoyed rights under jus gentium.

30 Comp. Cod. Thed. 16, 8, 29. Iudaeorum primates, qui in utriusque

Palaestinae synedriis nominantur vel in aliis provinciis degunt, quae-

cumque post excessum patriarcharum pensionis nomine suscepere, cogantur

exsolvere.

3' Iudaei Romano ... Sane si qui per conpromissum ad similitudinem

arbitrorum apud Iudaeos vel patriarchas ex concensu partium in civili

dumtaxat negotio putaverint litigandum sortiri eorum iudicium iure pub-

lico non vetentur: eorum etiam sententias provinciarum iudices exequantur,

tamquam ex sententia cognitoris arbitri fuerint ad tributi. Ibid. II, 1, 10.

Thus, in the year 398 C. E., in the time of the Emperors Arcadius and

Honorius, the Jewish patriarchs and the courts were recognized.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

134 THE JEWISH QUARTERLY REVIEW

the country but could not annex the title which the Romans

themselves did not possess. When the Turks conquered

Palestine from the Mamelukes, they, too, held the country

as an occupying power only. Thus the rights of the Arabs

and the Turks to Palestine were based on possession but

not on title. They never conquered Palestine from the Jews,

and the Jews never gave up title to the land.

In conclusion, we may say that Judaism is the only

religion and the Jews are the only people in the world

who, from earliest times to modern days, are identified

religiously, historically and legally with Palestine.

This content downloaded from

13.245.153.107 on Tue, 17 Oct 2023 16:08:58 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Jerusalem Crucified, Jerusalem Risen: The Resurrected Messiah, the Jewish People, and the Land of PromiseFrom EverandJerusalem Crucified, Jerusalem Risen: The Resurrected Messiah, the Jewish People, and the Land of PromiseRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Confort For The Jews (1925)Document129 pagesConfort For The Jews (1925)DAIRON TARLAO FRANCISCO DE CAMPOSNo ratings yet

- Watchtower: Jewish Hopes by Pastor Charles Taze Russell, 1910Document81 pagesWatchtower: Jewish Hopes by Pastor Charles Taze Russell, 1910sirjsslutNo ratings yet

- BIBLE STUDIES Grade 2Document34 pagesBIBLE STUDIES Grade 2amandaNo ratings yet

- Palestine The Rebirth of An Ancient People 1917Document344 pagesPalestine The Rebirth of An Ancient People 1917Magno Paganelli100% (1)

- Story of CoptsDocument371 pagesStory of CoptsGabriel Revens100% (3)

- The Inheritance of Abraham? A Report On The "Promised Land"Document10 pagesThe Inheritance of Abraham? A Report On The "Promised Land"LeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Unity and Diversity in ActsDocument7 pagesUnity and Diversity in ActsDyslexic100% (1)

- Bible Studies in the Life of Paul Historical and ConstructiveFrom EverandBible Studies in the Life of Paul Historical and ConstructiveNo ratings yet

- The Bible History, Old Testament, Volume 2: The Exodus and the Wanderings in the WildernessFrom EverandThe Bible History, Old Testament, Volume 2: The Exodus and the Wanderings in the WildernessNo ratings yet

- BREAD AND WINE (Robert Beecham)Document5 pagesBREAD AND WINE (Robert Beecham)Charles Cruickshank Mills-RobertsonNo ratings yet

- Mennonite Israel: The Woman in The WildernessDocument27 pagesMennonite Israel: The Woman in The WildernessAbraham RempelNo ratings yet

- Haggadah 2011 Small Group - Christian-MessianicDocument29 pagesHaggadah 2011 Small Group - Christian-MessianicDavid H PrichardNo ratings yet

- The Life of ChristDocument16 pagesThe Life of ChristMizaa ÖöNo ratings yet

- Bible Studies in the Life of Paul, Historical and ConstructiveFrom EverandBible Studies in the Life of Paul, Historical and ConstructiveNo ratings yet

- Intro To The Coptic ChurchDocument359 pagesIntro To The Coptic ChurchJoe HowardNo ratings yet

- Austral Asian Rec 11 11 1940Document8 pagesAustral Asian Rec 11 11 1940mdubard1No ratings yet

- Hosanna in The Highest - SwiftDocument12 pagesHosanna in The Highest - SwiftSaxon IngaNo ratings yet

- Romean (پلستين الروم الجريك) Greek Palestine 101Document25 pagesRomean (پلستين الروم الجريك) Greek Palestine 101Ámpou Aléxandros MáronNo ratings yet

- Shalom Rene,: Today (July 2)Document12 pagesShalom Rene,: Today (July 2)api-159226115No ratings yet

- What Is Nazarene Judaism - Dr. TrimmDocument30 pagesWhat Is Nazarene Judaism - Dr. Trimmdimitryorlovski100% (1)

- The Signs in The Heavens The Rise of Messianic State of IsraelDocument9 pagesThe Signs in The Heavens The Rise of Messianic State of IsraelCristiDucuNo ratings yet

- WHAT JERUSALEM MEANS TO US: Jewish Perspectives and Reflections:From EverandWHAT JERUSALEM MEANS TO US: Jewish Perspectives and Reflections:No ratings yet

- Is The New Testament Reliable?Document21 pagesIs The New Testament Reliable?thelightheartedcalvinist6903No ratings yet

- pp169 Mharel ThreeReligionsEDocument96 pagespp169 Mharel ThreeReligionsEYochanan Ezra ben Avraham de'HurstNo ratings yet

- Extra Biblical Evidences of The BibleDocument41 pagesExtra Biblical Evidences of The BibleLarryDelaCruzNo ratings yet

- Ingroups and OutgroupsDocument5 pagesIngroups and Outgroupsschreamonn5515No ratings yet

- Gods Perfect TimingDocument4 pagesGods Perfect TimingHenrique NápolesNo ratings yet

- A Tour To Ancient Israel BookletDocument23 pagesA Tour To Ancient Israel Bookletapi-264006204No ratings yet

- Quote BankDocument38 pagesQuote BankKurnaediOotNo ratings yet

- Bunch Taylor 40yearsDocument36 pagesBunch Taylor 40yearsNuno NevesNo ratings yet

- Bethlehem, The Basilica of The NativityDocument10 pagesBethlehem, The Basilica of The NativityDennis ToomeyNo ratings yet

- Kingdom of GodDocument8 pagesKingdom of Godwilfredo torres100% (1)

- Narratives in Conflict - F Cortez UPDATED - StampedDocument36 pagesNarratives in Conflict - F Cortez UPDATED - StampedReynold ZebaduaNo ratings yet

- Kerinduan Segala Zaman Jilid 1 Pasal 4 - 6 by Ellen G. WhitewritingsDocument6 pagesKerinduan Segala Zaman Jilid 1 Pasal 4 - 6 by Ellen G. WhitewritingsSengkey, Mario MalvinoNo ratings yet

- Good News 1961 (Vol X No 04) AprDocument16 pagesGood News 1961 (Vol X No 04) AprHerbert W. ArmstrongNo ratings yet

- Art The Missing YearsDocument12 pagesArt The Missing YearsAnonymous gdJiDHNo ratings yet

- Commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians: The New Testament ExegesisFrom EverandCommentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians: The New Testament ExegesisNo ratings yet

- Sketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of ChristFrom EverandSketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of ChristRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Acts 6:8 - 7:8Document9 pagesActs 6:8 - 7:8Sue WetherellNo ratings yet

- ContinueDocument2 pagesContinueAqeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Thy 1 The Context of The 1st Cent WorldDocument4 pagesThy 1 The Context of The 1st Cent WorldMich TolentinoNo ratings yet

- A Rastafari Passover Haggadah 3 ADocument138 pagesA Rastafari Passover Haggadah 3 ALexingtonluv100% (1)

- The Palestinian Delusion: The Catastrophic History of the Middle East Peace ProcessFrom EverandThe Palestinian Delusion: The Catastrophic History of the Middle East Peace ProcessRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Appropriating The Holy Land - Sacred Space in Crusader EuropeDocument11 pagesAppropriating The Holy Land - Sacred Space in Crusader Europeapi-301894375No ratings yet

- 40 2 pp189 197 - JETSDocument9 pages40 2 pp189 197 - JETSmilkymilky9876No ratings yet

- Kingdom of GodDocument16 pagesKingdom of GodBarry LeBlancNo ratings yet

- (BB) Advanced Training Step by StepDocument2 pages(BB) Advanced Training Step by StepWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Day 3 SPS Guide 2019Document5 pagesDay 3 SPS Guide 2019Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Day 2 SPS Guide 2019Document9 pagesDay 2 SPS Guide 2019Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Manual Rev.1.0 231204Document174 pagesManual Rev.1.0 231204Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- 0how To Submit A SafeAssignmentDocument4 pages0how To Submit A SafeAssignmentWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Supervisor Student Alignment Tool KitDocument13 pagesSupervisor Student Alignment Tool KitWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Sept 2019 SPS-2Document6 pagesSept 2019 SPS-2Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- JulyDocument1 pageJulyWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- July 2019. WinbergDocument1 pageJuly 2019. WinbergWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- 0task 4 EkatarinaDocument1 page0task 4 EkatarinaWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Industrial Engineering-A Brief IntroDocument14 pagesIndustrial Engineering-A Brief IntroWilly K. Ng'etich100% (1)

- Self Exploration QuestionsDocument2 pagesSelf Exploration QuestionsWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Oct 2019 SPSDocument3 pagesOct 2019 SPSWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- EOQ Problems PDFDocument3 pagesEOQ Problems PDFWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Task 3-CPUT Postgraduate Policies and Processes - CPUT Research PoliciesDocument2 pagesTask 3-CPUT Postgraduate Policies and Processes - CPUT Research PoliciesWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Overall Equipment Effectiveness GuideDocument117 pagesOverall Equipment Effectiveness GuideWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Turning Men Into Machines Scientific Management, Industrial Psychology, and The "Human Factor"Document36 pagesTurning Men Into Machines Scientific Management, Industrial Psychology, and The "Human Factor"Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- DHBW Guidelines For Practical Training PhasesDocument15 pagesDHBW Guidelines For Practical Training PhasesWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- EFRC1.1 - Checklist and Evaluation of Dissertation / Thesis ProposalDocument2 pagesEFRC1.1 - Checklist and Evaluation of Dissertation / Thesis ProposalWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Management Reporting Systems-MRSDocument1 pageManagement Reporting Systems-MRSWilly K. Ng'etich100% (3)

- Prof Kris Adendorff: by H PostedDocument1 pageProf Kris Adendorff: by H PostedWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Is OEE OutdatedDocument3 pagesIs OEE OutdatedWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Approaches For Different Production Methods-Mungani & VisserDocument13 pagesMaintenance Approaches For Different Production Methods-Mungani & VisserWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Work Measurement Sample (Coding Ans)Document2 pagesWork Measurement Sample (Coding Ans)Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- EWY 100S Subject GuideDocument6 pagesEWY 100S Subject GuideWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning QuestionnaireDocument1 pageProblem-Based Learning QuestionnaireWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- LSE400S Tutorial 1Document1 pageLSE400S Tutorial 1Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- LSE400S Tutorial 2-ReliabilityDocument2 pagesLSE400S Tutorial 2-ReliabilityWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Student Welcome - OrientationDocument2 pagesStudent Welcome - OrientationWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Logistics - A Total System's Approach - Benjamin S BlanchardDocument8 pagesLogistics - A Total System's Approach - Benjamin S BlanchardWilly K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Entry CheckerDocument32 pagesEntry CheckerJosé Sánchez Ramos100% (1)

- Mass of Christ The Savior by Dan Schutte LyricsDocument1 pageMass of Christ The Savior by Dan Schutte LyricsMark Greg FyeFye II33% (3)

- Existentialist EthicsDocument6 pagesExistentialist EthicsCarlos Peconcillo ImperialNo ratings yet

- ARI - Final 2Document62 pagesARI - Final 2BinayaNo ratings yet

- Player's Guide: by Patrick RenieDocument14 pagesPlayer's Guide: by Patrick RenieDominick Bryant100% (4)

- Army Aviation Digest - Jan 1994Document56 pagesArmy Aviation Digest - Jan 1994Aviation/Space History Library100% (1)

- Traditions and Encounters 3Rd Edition Bentley Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument49 pagesTraditions and Encounters 3Rd Edition Bentley Test Bank Full Chapter PDFsinhhanhi7rp100% (7)

- Cmvli DigestsDocument7 pagesCmvli Digestsbeth_afanNo ratings yet

- Internship Final Students CircularDocument1 pageInternship Final Students CircularAdi TyaNo ratings yet

- Catalogue of CCP Publications 2021Document75 pagesCatalogue of CCP Publications 2021marcheinNo ratings yet

- Deanne Mazzochi Complaint Against DuPage County Clerk: Judge's OrderDocument2 pagesDeanne Mazzochi Complaint Against DuPage County Clerk: Judge's OrderAdam HarringtonNo ratings yet

- 35 Childrens BooksDocument4 pages35 Childrens Booksapi-710628938No ratings yet

- Com Ad Module 2Document10 pagesCom Ad Module 2Gary AlaurinNo ratings yet

- Ebook4Expert Ebook CollectionDocument42 pagesEbook4Expert Ebook CollectionSoumen Paul0% (1)

- A Tuna ChristmasDocument46 pagesA Tuna ChristmasMark100% (3)

- BPM at Hindustan Coca Cola Beverages - NMIMS, MumbaiDocument10 pagesBPM at Hindustan Coca Cola Beverages - NMIMS, MumbaiMojaNo ratings yet

- Creating A Carwash Business PlanDocument7 pagesCreating A Carwash Business PlanChai Yeng LerNo ratings yet

- Alcpt 27R (Script)Document21 pagesAlcpt 27R (Script)Matt Dahiam RinconNo ratings yet

- Who Am I NowDocument7 pagesWho Am I Nowapi-300966994No ratings yet

- My Father's Goes To Cour 12-2Document34 pagesMy Father's Goes To Cour 12-2Marlene Rochelle Joy ViernesNo ratings yet

- Soal Asking and Giving OpinionDocument2 pagesSoal Asking and Giving OpinionfitriaNo ratings yet

- Zero Trust Deployment Plan 1672220669Document1 pageZero Trust Deployment Plan 1672220669Raj SinghNo ratings yet

- 55WeekScheduleforFOUNDATION Pouyrogram-CrackiasDocument21 pages55WeekScheduleforFOUNDATION Pouyrogram-CrackiasThowheedh MahamoodhNo ratings yet

- Aud Prob Compilation 1Document31 pagesAud Prob Compilation 1Chammy TeyNo ratings yet

- Zmaja Od Bosne BB, UN Common House, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Tel: +387 33 293 400 Fax: +387 33 293 726 E-Mail: Missionsarajevo@iom - Int - InternetDocument5 pagesZmaja Od Bosne BB, UN Common House, 71000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Tel: +387 33 293 400 Fax: +387 33 293 726 E-Mail: Missionsarajevo@iom - Int - InternetavatarpetrovicNo ratings yet

- Trade Infrastructure (Maharashtra)Document5 pagesTrade Infrastructure (Maharashtra)RayNo ratings yet

- Orwell's 1984 & Hegemony in RealityDocument3 pagesOrwell's 1984 & Hegemony in RealityAlex JosephNo ratings yet

- Commercial Banks in IndiaDocument14 pagesCommercial Banks in IndiaAnonymous UwYpudZrANo ratings yet

- CorinnamunteanDocument2 pagesCorinnamunteanapi-211075103No ratings yet

- SwingDocument94 pagesSwinggilles TedonkengNo ratings yet