Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paediatric Caudal Anaesthesia Update 2010

Paediatric Caudal Anaesthesia Update 2010

Uploaded by

Aashik 249Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paediatric Caudal Anaesthesia Update 2010

Paediatric Caudal Anaesthesia Update 2010

Uploaded by

Aashik 249Copyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Overview Articles

Update in

Anaesthesia

Paediatric caudal anaesthesia

O Raux, C Dadure, J Carr, A Rochette, X Capdevila

Correspondence Email: Bruce.McCormick@rdeft.nhs.uk

INDICATIONS FOR CAUDAL ANAESTHESIA S5 articular processes and which face the coccygeal

The indications for single shot CA are abdominal, cornua. Palpation of the sacral cornua is fundamental

urologic or orthopaedic surgical procedures located to locating the sacral hiatus and to successful caudal

in the sub-umbilical abdominal, pelvic and genital block.

areas, or the lower limbs, where postoperative pain

does not require prolonged strong analgesia. Examples

of appropriate surgery include inguinal or umbilical

Summary

herniorrhaphy, orchidopexy, hypospadias and club foot

Caudal anaesthesia (CA) surgery. CA is useful for day case surgery, but opioid

is epidural anaesthesia of

additives to the local anesthetic agent should be avoided

the cauda equina roots in

the sacral canal, accessed in this setting. When CA is used, requirement for mild

through the sacral hiatus. or intermediate systemic analgesia must be anticipated

CA is a common paediatric to prevent pain resurgence at the end of caudal block.

regional technique that is Catheter insertion can extend the indications to include

quick to learn and easy to surgical procedures located in the high abdominal

perform, with high success or thoracic areas, and to those requiring prolonged

and low complication rates. effective analgesia.

CA provides high quality

intraoperative and early CONTRAINDICATIONS

postoperative analgesia The usual contraindications to regional anaesthesia

for sub-umbilical surgery. such as coagulation disorders, local or general infection,

In children, CA is most

progressive neurological disorders and patient or

effectively used as adjunct

to general anaesthesia parental refusal apply to CA. Furthermore, cutaneous

Figure 1. The posterior aspect of the sacrum and sacral

and has an opioid-sparing anomalies (angioma, hair tuft, naevus or a dimple) near

hiatus

effect, permitting faster and the puncture point require radiological examination

smoother emergence from (ultrasound, CT or MRI), in order to rule out The sacral hiatus is the shape of an inverted U, and

anaesthesia. underlying spinal cord malformation such as a tethered is covered by the sacro-coccygeal ligament, which

cord.23 A Mongolian spot is not a contraindication to is in continuity with the ligamentum flavum. It is

CA. large and easy to locate until 7-8 years of age. Later,

progressive ossification of the sacrum (until 30 years

ANATOMY old) and closing of the sacro-coccygeal angle make its

identification more difficult. Note that anatomical

Anatomical landmarks (Figure 1)

anomalies of the sacral canal roof are observed in 5%

The sacrum is roughly the shape of an equilateral

of patients and this can lead to unplanned cranial or

triangle, with its base identified by feeling the two

O Raux lateral puncture.

posterosuperior iliac processes and a caudal summit

C Dadure

corresponding to the sacral hiatus. The sacrum is

J Carr The sacral canal

concave anteriorly. The dorsal aspect of the sacrum

A Rochette The sacral canal is in continuity with the lumbar

consists of a median crest, corresponding to the

X Capdevila epidural space. It contains the nerve roots of the

fusion of sacral spinous processes. Moving laterally,

Département d’Anesthésie cauda equina, which leave it through anterior sacral

intermediate and lateral crests correspond respectively

Réanimation foraminae. During CA, leakage of local anaesthetic

to the fusion of articular and transverse processes.

Centre Hospitalo- agent (LA) through these foraminae explains the

Universitaire Lapeyronie The sacral hiatus is located at the caudal end of the high quality of analgesia, attributable to diffusion of

Montpellier median crest and is created by failure of the S5 laminae LA along the nerve roots. Spread of analgesia cannot

France to fuse (Figure 1). The hiatus is surrounded by the be enhanced above T8-T9 by increasing injected LA

CHU Montpellier sacral cornua, which represent remnants of the inferior volume.

page 32 Update in Anaesthesia | www.anaesthesiologists.org

The dural sac (i.e. the subarachnoid space) ends at the level of S3 in

infants and at S2 in adults and children. It is possible to puncture

the dural sac accidentally during CA, leading to extensive spinal

anaesthesia. Therefore the needle or cannula must be cautiously

advanced into the sacral canal, after crossing the sacro-coccygeal

ligament. The distance between the sacral hiatus and the dural sac

is approximately 10mm in neonates. It increases progressively with

age (>30mm at 18 years), but there is significant inter-individual

variability in children.1 The contents of sacral canal are similar to those

of lumbar epidural space, predominantly fat and epidural veins. In

children, epidural fatty tissue is looser and more fluid than in adults,

favoring LA diffusion.

TECHNIQUE

Preparation

Obtain consent for the procedure either from the patient or, if

appropriate, from the parents. After induction of general anaesthesia Figure 3. Bony landmarks

and airway control, the patient is positioned laterally (or ventrally), is between 5 and 15mm, depending on the child’s size. The sacro-

with their hips flexed to 90° (Figure 2). Skin disinfection should be coccygeal ligament gives a perceptible ‘pop’ when crossed, analogous

performed carefully, because of the proximity to the anus. Aseptic to the ligamentum flavum during lumbar epidural anaesthesia. After

technique should be maintained. crossing the sacro-coccygeal ligament, the needle is redirected 30° to

the skin surface, and then advanced a few millimeters into sacral canal.

If in contact with the bony ventral wall of sacral canal, the needle must

be moved back slightly.

Figure 2. Preparation of patient - lateral position with the surgical site

down

According to the child’s size, needle diameter and length are

respectively between 21G and 25G, and 25mm and 40mm. A short

bevel improves the feeling of sacrococcygeal ligament penetration Figure 4. Puncture - orientation of the needle and reorientation after

and decreases risk of vascular puncture or sacral perforation.2 Use of crossing the sacro-coccygeal ligament.

a needle with a stylet avoids risk of cutaneous tissue coring, and the

(theoretical) risk of epidural cutaneous cell graft. If a styletted needle

is not available, a cutaneous ‘pre-hole’ can be made with a different

needle prior to puncture with the caudal needle. Another solution is to

puncture with an IV catheter, the hollow needle of which is removed

before injection through the sheath.

Puncture (Figures 3, 4 and 5)

After defining the bony landmarks of the sacral triangle, the two sacral

cornuae are identified by moving your fingertips from side to side.

Figure 5. Orientation of the needle during puncture

The gluteal cleft is not a reliable mark of the midline. The puncture

is performed between the two sacral cornuae. The needle is oriented After verifying absence of spontaneous reflux of blood or cerebrospinal

60° in relation to back plane, 90° to skin surface. The needle bevel fluid (more sensitive than an aspiration test), injection of LA should

is oriented ventrally, or parallel to the fibers of the sacro-coccygeal be possible be without resistance. Inject slowly (over about one

ligament. The distance between the skin and sacro-coccygeal ligament minute). Where available this may be preceded with an epinephrine

Update in Anaesthesia | www.anaesthesiologists.org page 33

test dose under ECG and blood pressure monitoring, in order to Catheter insertion

detect intravascular placement. Subcutaneous bulging at the injection Although CA was initially described as a single shot technique, some

site suggests needle misplacement. Blood reflux necessitates repeating authors have described use of a caudal catheter to prolong analgesic

the puncture, however in case of cerebrospinal fluid reflux caudal administration in postoperative period. In addition advancement

anaesthesia should be abandoned, in order to avoid the risk of extensive of the catheter in the epidural space up to lumbar or even thoracic

spinal anaesthesia. Aspiration tests should be repeated several times levels can achieve analgesia of high abdominal or thoracic areas.8

during injection. However, two pitfalls restrict extension of this technique; a high

risk of catheter bacterial colonization, particularly in infants and a

In skilled hands, the success rate of CA is about 95%, however a variety

high risk of catheter misplacement.9,10 Subcutaneous tunnelling at a

of misplacements of the needle are possible (Figure 6). The moment of

distance from the anal orifice, or occlusive dressings decrease bacterial

surgical incision is the true test of block success, but various techniques

colonization.11 Electrical nerve stimulation or ECG recording on the

have been suggested to authenticate the puncture success, such as

catheter, or its echographic visualization have been suggested to guide

injection site auscultation (the ‘swoosh test’), or searching for anal

its advancement in epidural space.12,13 However, most anaesthetists

sphincter contraction in response to electrical nerve stimulation on the

presently prefer a direct epidural approach at the desired level that is

puncture needle. No clear benefit of these techniques against simple

appropriate to the surgical intervention.14,15

clinical assessment have been shown.3,4 More recently, ultrasound has

been suggested to help sacro-coccygeal hiatus location and to visualize

isotonic serum or LA injection into sacral epidural space (Figures 7

and 8).5,6 These authors have also outlined the interest in ultrasound

control within the context of learning the technique, rather than for

use in standard practice.5,7

Figure 7.

Figures 8a and 8b.

LOCAL ANAESTHETIC AGENTS

Test dose

Early neurosensory warning symptoms of LA systemic toxicity are

concealed by general anaesthesia. Halogenated anaesthetic agents

worsen LA systemic toxicity and can also blunt the cardiovascular signs

Figure 6A and B. Needle misplacement of an intravenous epinephrine test dose injection. Aspiration tests to

A marrow (resistance +++. Equivalent to IV injection) elicit blood reflux are not very sensitive, particularly in infants. A test

B posterior sacral ligament (subcutaneous bulge) dose of epinephrine 0.5mcg.kg-1 (administered as 0.1ml.kg-1 lidocaine

with epinephrine 1 in 200 000) allows detection of intravenous

C subperiostal

injection with sensitivity and specificity close to 100%, under

D “decoy” hiatus

halogenated anaesthesia. Warning symptoms are cardiac frequency

E intrapelvic (risk of damaging intrapelvic structures: rectum) modification (an increase or decrease by 10 beats per minute), increased

F 4th sacral foramen (unilateral block). in blood pressure (up to 15mmHg), or T-wave amplitude change in

page 34 Update in Anaesthesia | www.anaesthesiologists.org

Figure 9. T-wave amplitude change after intravascular injection of a local anaesthetic agent

the 60 to 90 second period after injection (Figure 9).16,17 Slow injection Additives

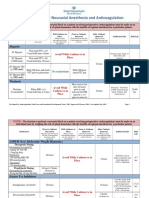

of the whole LA dose under haemodynamic and ECG monitoring Tables 3. Several additives prolong CA duration when added to LA.

remains essential for patient safety.

Additive agent Dose/concentration

Full dose

The volume of caudally injected LA determines the spread of the block epinephrine 5mcg.ml-1

and this must be adapted to surgical procedure (Table 1). Analgesic fentanyl 1mcg.kg-1

spread will be two dermatomes higher on the down positioned side at

clonidine 1-2mcg.kg-1

the time of puncture. Injected volume must not exceed 1.25 ml.kg-1 or

20 to 25ml, in order to avoid excessive cerebrospinal fluid pressure. preservative-free S(+) ketamine 0.5mg.kg-1

(note - not the intravenous form)

Table 1. Spread of block as a function of caudally injected local

anaesthetic volume18

COMPLICATIONS

Volume (ml.kg-1) Dermatomal level Indication Complications of CA are uncommon (0.7 per 1000 cases), are

more likely if inadequate equipment is used and are more frequent

0.5 Sacral Circumcision

in infants.16 If the technique fails it should be abandoned to avoid

0.75 Inguinal Inguinal occurrence of potentially serious complications.

herniotomy

1 Lower thoracic (T10) Umbilical Significant complications, in order of decreasing frequency, are:

herniorraphy, • Dural tap. This is more likely if the needle is advanced excessively in the

orchidopexy

sacral canal when subarachnoid injection of local anaesthetic agent may

1.25 Mid thoracic cause extensive spinal anaesthesia. Under general anaesthesia this

should be suspected if non-reactive mydriasis (pupillary dilation)

LA choice prioritizes long lasting effects with the weakest motor block is observed.

possible, since motor block is poorly tolerated in awake children.

Bupivacaine meets these criteria. More recently available, ropivacaine • Vascular or bone puncture can lead to intravascular injection and

and L-bupivacaine have less cardiac toxicity than bupivacaïne at consequently LA systemic toxicity. Preventative measures are use of

equivalent analgesic effectiveness. They may also confer a more a test dose, cessation of injection if resistance is felt and slow

favorable differential block (less motor block for the same analgesic injection under hemodynamic and ECG monitoring. Sacral

power) and the 2.5mg.ml-1 (0.25%) concentration is optimal for these perforation can lead to pelvic organ damage (e.g. rectal

agents. Four to six hours analgesia is usually achieved with minimal puncture).

motor block.19,20 • Exceeding the maximal allowed LA dose risks overdose and related

Maximal doses must not be exceeded (Table 2) but use of a more cardiovascular or neurological complications.

dilute mixture may allow the desired volume to be achieved within • Delayed respiratory depression secondary to caudally injected

the recommended maximum dose. Hemodynamic effects of CA opioid.

are weak or absent in children, so intravenous fluid preloading or

vasoconstrictive drugs are unnecessary. • Urinary retention - spontaneous micturition must be observed

before hospital discharge.

Table 2. Maximal allowable doses of local anaesthestic agents

• Sacral osteomyelitis is rare (one case report).22

Plain local With epinephrine

anaesthetic (mg.kg-1) (mg.kg-1) Neonates CONCLUSION

This technique has an established role in paediatric regional anaesthesia

Bupivacaine 2 2

practice since it is easy to learn and has a favorable risk/benefit ratio.

Lidocaine 3 7 ‚ 20% Despite being more complex to learn, alternative peripheral regional

Ropivacaine 3 3 anaesthesia techniques are gaining popularity and may begin to replace

caudal anaesthesia as a popular choice.

Update in Anaesthesia | www.anaesthesiologists.org page 35

REFERENCES 13. Chawathe MS, Jones RM, Gildersleve CD, Harrison SK, Morris SJ,

Eickmann C. Detection of epidural catheters with ultrasound in

1. Adewale L, Dearlove O, Wilson B, Hindle K, Robinson DN. The caudal

children. Paediatr Anaesth 2003; 13: 681-4.

canal in children: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. Paediatr

Anaesth 2000; 10: 137-41. 14. Bösenberg AT. Epidural analgesia for major neonatal surgery. Paediatr

2. Dalens B, Hasnaoui A. Caudal anesthesia in pediatric surgery: success Anaesth 1998; 8: 479-83.

rate and adverse effects in 750 consecutive patients. Anesth analg

1989; 68: 83-9. 15. Giaufré E, Dalens B, Gombert A. Epidemiology and morbidity of

regional anesthesia in children: a one-year prospective survey of the

3. Orme RM, Berg SJ. The “swoosh” test - an evaluation of a modified French-language society of pediatric anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg

“whoosh” test in children. Br J Anaesth 2003; 90: 62-5. 1996; 83: 904-12.

4. Tsui BC, Tarkkila P, Gupta S, Kearney R. Confirmation of caudal needle 16. Kozek-Langenecker SA, Marhofer P, Jonas K, Macik T, Urak G, Semsroth

placement using nerve stimulation. Anesthesiology 1999; 91: 374-8. M. Cardiovascular criteria for epidural test dosing in sevoflurane- and

5. Raghunathan K, Schwartz D, Conelly NR. Determining the accuracy halothane-anesthetized children. Anesth Analg 2000; 90: 579-83.

of caudal needle placement in children: a comparison of the swoosh

test and ultrasonography. Paediatr Anaesth 2008; 18: 606-12. 17. Tobias JD. Caudal epidural block: a review of test dosing and

recognition injection in children. Anesth Analg 2001; 93: 1156-61.

6. Roberts SA, Guruswamy V, Galvez I. Caudal injectate can be reliably

imaged using portable ultrasound - a preliminary result. Paediatr 18. Armitage EN. Local anaesthetic techniques for prevention of

anaesth 2005; 15: 948-52. postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth 1986; 58: 790-800.

7. Schwartz DA, Dunn SM, Conelly NR. Ultrasound and caudal blocks in 19. Bösenberg AT, Thomas J, Lopez T, Huledal G, Jeppsson L, Larsson LE.

children. Paediatr Anaesth 2006; 16: 892-902 (correspondence). Plasma concentrations of ropivacaine following a single-shot caudal

8. Tsui BC, Berde CB. Caudal analgesia and anesthesia techniques in block of 1, 2 or 3 mg/kg in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2001; 10:

children. Curr Op Anesthesiol 2005; 18: 283-8. 1276-80.

9. Kost-Byerly S, Tobin JR, Greenberg RS, Billett C, Zahurak M, Yaster M. 20. Breschan C, Jost R, Krumpholz R, Schaumberger F, Stettner H,

Bacterial colonisation and infectious rate of continuous epidural Marhofer P, Likar R. A prospective study comparing the analgesic

catheters in children. Anesth Analg 1998; 86: 712-6. efficacy of levobupivacaine, ropivacaine and bupivacaine in pediatric

10. Valairucha S, Seefelder D, Houck CS. Thoracic epidural catheters patients undergoing caudal blockade. Paediatr Anaesth 2005; 15:

placed by the caudal route in infants: the importance of radiographic 301-6.

confirmation. Paediatr Anaesth 2002; 12: 424-8. 21. Sanders JC. Paediatric regional anaesthesia, a survey of practice in the

11. Bubeck J, Boss K, Krause H, Thies KC. Subcutaneous tunneling of United Kingdom. Br J Anaesth 2002; 89: 707-10.

caudal catheters reduces the rate of bacterial colonization to that of

lumbar epidural catheters. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 689-93. 22. Wittum S, Hofer CK, Rölli U, Suhner M, Gubler J, Zollinger A. Sacral

osteomyelitis after single-shot epidural anesthesia via the caudal

12. Tsui BC, Wagner A, Cave D, Kearny R. Thoracic and lumbar epidural approach in a child. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 503-5.

analgesia via the caudal approach using electrical stimulation

guidance in pediatric patients: a review of 289 patients. Anesthesiology 23. Cohen IT. Caudal block complication in a patient with trisomy 13.

2004; 100: 683-9. Paediatr Anaesth 2006; 16: 213-5.

page 36 Update in Anaesthesia | www.anaesthesiologists.org

You might also like

- Adhd Add Adult TestDocument1 pageAdhd Add Adult Testlogan50% (2)

- General-Anesthesia Part 5Document4 pagesGeneral-Anesthesia Part 5Dianne GalangNo ratings yet

- Trauma Module FinalDocument34 pagesTrauma Module FinalMarian YuqueNo ratings yet

- Pauling - The Vitamin C Theory of Heart Disease - by - Owen - FonorrowDocument5 pagesPauling - The Vitamin C Theory of Heart Disease - by - Owen - FonorrowAnonymous Jap77xvqPKNo ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetics of Inhalation AnestheticsDocument24 pagesPharmacokinetics of Inhalation AnestheticsKinanta DewiNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Anaesthesia For Postgraduates PDFDocument1,218 pagesTextbook of Anaesthesia For Postgraduates PDFMohammad HayajnehNo ratings yet

- The Preoperative EvaluationDocument25 pagesThe Preoperative Evaluationnormie littlemonsterNo ratings yet

- BASIC Exam Blueprint PDFDocument3 pagesBASIC Exam Blueprint PDFmichael100% (1)

- CH 21 Obstetric AnaesthesiaDocument39 pagesCH 21 Obstetric AnaesthesiaChristian LeepoNo ratings yet

- Pig Care ManualDocument301 pagesPig Care ManualFranklin Martinez100% (3)

- Anesthesia - State of Narcosis, Analgesia, Relaxation, and Loss of Reflex. Effects of AnesthesiaDocument3 pagesAnesthesia - State of Narcosis, Analgesia, Relaxation, and Loss of Reflex. Effects of AnesthesiaJhevilin RMNo ratings yet

- ACE 2007 4A QuestionsDocument29 pagesACE 2007 4A QuestionsRachana GudipudiNo ratings yet

- Fred Rotenberg, MD Dept. of Anesthesiology Rhode Island Hospital Grand Rounds February 27, 2008Document53 pagesFred Rotenberg, MD Dept. of Anesthesiology Rhode Island Hospital Grand Rounds February 27, 2008lmjeksoreNo ratings yet

- Decreased Cardiac OutputDocument9 pagesDecreased Cardiac OutputRae AnnNo ratings yet

- Regional Anesthesia Made Easy 2015Document35 pagesRegional Anesthesia Made Easy 2015Jeff GulitisNo ratings yet

- Complications of Spinal and Epidural AnesthesiaDocument45 pagesComplications of Spinal and Epidural AnesthesiashikhaNo ratings yet

- Obs QuestionsDocument14 pagesObs QuestionsMasseh YakubiNo ratings yet

- FCA 2 Trials MindmapDocument1 pageFCA 2 Trials MindmapameenallyNo ratings yet

- Management of Failed Block - Harsh.Document48 pagesManagement of Failed Block - Harsh.Faeiz KhanNo ratings yet

- 4 Medical Terminology, in The Hospital, Nursing Roles AdmissionsDocument16 pages4 Medical Terminology, in The Hospital, Nursing Roles AdmissionsAnabel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Caudal Anesthesia - NYSORADocument27 pagesCaudal Anesthesia - NYSORApradeep daniel100% (1)

- Telegram Cloud Document 4 5893461163299045618 PDFDocument232 pagesTelegram Cloud Document 4 5893461163299045618 PDFAndreea FlorinaNo ratings yet

- Drugs & Machine (Equipments), Airway, Monitoring: Page 1 of 33Document33 pagesDrugs & Machine (Equipments), Airway, Monitoring: Page 1 of 33Shiladitya Roy100% (2)

- Preanesthetic Medication JasminaDocument44 pagesPreanesthetic Medication Jasminaanjali sNo ratings yet

- Epidural AnaesthesiaDocument13 pagesEpidural AnaesthesiajuniorebindaNo ratings yet

- Induction AgentsDocument100 pagesInduction AgentsSulfikar TknNo ratings yet

- Title Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Orthognathic SurgeryDocument80 pagesTitle Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Orthognathic SurgeryKuriyan ArimboorNo ratings yet

- Kidney Cancer Principles and Practice by Primo N. Lara, Eric JonaschDocument400 pagesKidney Cancer Principles and Practice by Primo N. Lara, Eric JonaschCoralina100% (2)

- Extubation After AnaesthesiaDocument7 pagesExtubation After AnaesthesiaaksinuNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Bariatric SurgeryDocument47 pagesAnesthesia For Bariatric Surgerydkhiloi100% (1)

- Venous Air EmbolismDocument16 pagesVenous Air EmbolismEylia MelikaNo ratings yet

- Brachial Plexus BlockDocument13 pagesBrachial Plexus BlockAnkit Shah100% (1)

- Lippincott S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions And.20Document1 pageLippincott S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions And.20Reem Salem0% (1)

- Neonatal ResuscitationDocument7 pagesNeonatal ResuscitationJavier López García100% (1)

- MCQs 2010 Anaesthesia Intensive Care Medicine72Document1 pageMCQs 2010 Anaesthesia Intensive Care Medicine72luxedeNo ratings yet

- ITLC Questions 2019Document9 pagesITLC Questions 2019Neil ThomasNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia in Liver Disease PatientDocument49 pagesAnaesthesia in Liver Disease PatientVG FernandezNo ratings yet

- Anestesia Pediatrica 2015Document292 pagesAnestesia Pediatrica 2015Eloy BurdaNo ratings yet

- Post Op DeliriumDocument26 pagesPost Op DeliriumKannan GNo ratings yet

- Update EmergenciesDocument84 pagesUpdate EmergenciesElaineNo ratings yet

- 21 Obstetric Anaesthesia PDFDocument0 pages21 Obstetric Anaesthesia PDFjuniorebindaNo ratings yet

- CCrISP-13-Nutrition and The Surgical PatientDocument27 pagesCCrISP-13-Nutrition and The Surgical Patientpioneer92No ratings yet

- Failed Spinal Anesthesia PDFDocument2 pagesFailed Spinal Anesthesia PDFShamim100% (1)

- Anesthetic AgentsDocument7 pagesAnesthetic AgentsJan DacioNo ratings yet

- Usual Diluents: IsoprenalineDocument1 pageUsual Diluents: IsoprenalineGlory Claudia KarundengNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument4 pagesDocument PDFDebasis SahooNo ratings yet

- Advanced Airway: Lynn K. Wittwer, MD, MPD Clark County EMSDocument56 pagesAdvanced Airway: Lynn K. Wittwer, MD, MPD Clark County EMSiaaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Thyroid Surgery....Document46 pagesAnaesthesia For Thyroid Surgery....Parvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Dengue Fever in Pregnancy 2Document37 pagesDengue Fever in Pregnancy 2Kevin AgbonesNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For GeriatricDocument21 pagesAnesthesia For GeriatricintanNo ratings yet

- STAGES of AnesthesiaDocument4 pagesSTAGES of AnesthesiaMabz Posadas BisnarNo ratings yet

- Journal ClubDocument26 pagesJournal Clubysindhura23gmailcom100% (1)

- Premedication: by Alif Moderator: Dr. JasmineDocument45 pagesPremedication: by Alif Moderator: Dr. JasmineAlef AminNo ratings yet

- MCQ-Multimedia Test 6th Periodical With Key, Mon July 22, 2019 (KEY)Document37 pagesMCQ-Multimedia Test 6th Periodical With Key, Mon July 22, 2019 (KEY)Amara AsifNo ratings yet

- AnaesthesiaDocument5 pagesAnaesthesiaAnonymous 4jkFIRalKNo ratings yet

- Severity Scoring Systems in The Critically IllDocument5 pagesSeverity Scoring Systems in The Critically Illdefitrananda100% (1)

- Anesthesia ManualDocument21 pagesAnesthesia ManualDocFrankNo ratings yet

- Regional Anesthesia - FinalDocument46 pagesRegional Anesthesia - Finalvan016_bunnyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric AnesthesiaDocument70 pagesPediatric AnesthesiaEliyan KhanimovNo ratings yet

- Trends in Anasthesia and Critical CareDocument6 pagesTrends in Anasthesia and Critical CareNurLatifah Chairil AnwarNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Considerations in HELLP Syndrome PDFDocument14 pagesAnesthetic Considerations in HELLP Syndrome PDFGustavo ParedesNo ratings yet

- Pulsus ParadoxusDocument2 pagesPulsus ParadoxusHassan.shehriNo ratings yet

- Acute Burns, Post-Burn Contracture, &TMJ Ankylosis (EORCAPS-2009)Document15 pagesAcute Burns, Post-Burn Contracture, &TMJ Ankylosis (EORCAPS-2009)Parvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Essentials of AnesthesiologyDocument2 pagesEssentials of AnesthesiologymanabdebuNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Caudal AnaesthesiaDocument5 pagesPaediatric Caudal AnaesthesiaSuresh KumarNo ratings yet

- Female Case PCTLDocument4 pagesFemale Case PCTLDewi Eli SantiNo ratings yet

- Harar Health Science CollegeDocument45 pagesHarar Health Science Collegeheysem100% (1)

- Tata Kelola DM Di FKTPDocument29 pagesTata Kelola DM Di FKTPRSTN BoalemoNo ratings yet

- Normal Flora of Human BodyDocument15 pagesNormal Flora of Human BodyFrancia ToledanoNo ratings yet

- For Drug Recitation 1Document33 pagesFor Drug Recitation 1Abigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Acute Management of Open Fractures: An Evidence-Based ReviewDocument23 pagesAcute Management of Open Fractures: An Evidence-Based ReviewerdiansyahzuldiNo ratings yet

- Dr. Sumait Hospital: Final Investigation ReportDocument10 pagesDr. Sumait Hospital: Final Investigation ReportShafici CqadirNo ratings yet

- Genotype: The Ability of The Virus To Mutate Has Resulted in The Existence of Different Genetic Variation of (HCV)Document5 pagesGenotype: The Ability of The Virus To Mutate Has Resulted in The Existence of Different Genetic Variation of (HCV)adeeb hamzaNo ratings yet

- PQRI - Biosimilar USADocument27 pagesPQRI - Biosimilar USANgoc Sang HuynhNo ratings yet

- Genetic Disorders Chromosomal Disorders: Multifactorial Inheritance Trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome)Document4 pagesGenetic Disorders Chromosomal Disorders: Multifactorial Inheritance Trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome)Sakshi YadavNo ratings yet

- Mapeh8 - Health - Q2 Las RPMSDocument2 pagesMapeh8 - Health - Q2 Las RPMSAlbert Ian CasugaNo ratings yet

- Sample Pages of MBBS Decode (MGR University)Document20 pagesSample Pages of MBBS Decode (MGR University)vkNo ratings yet

- Acute Tubular NecrosisDocument38 pagesAcute Tubular Necrosisganesa ekaNo ratings yet

- 2nd AnnouncementDocument2 pages2nd AnnouncementFauzan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis and Workplace PoliciesDocument5 pagesEndometriosis and Workplace PoliciesMimi RoyNo ratings yet

- 13 Purpose and Problems of Periodontal Disease ClassificationDocument9 pages13 Purpose and Problems of Periodontal Disease ClassificationEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Liver Function Tests SummaryDocument2 pagesLiver Function Tests SummaryAdrian CastroNo ratings yet

- The Surgical Treatment of Morton's NeuromaDocument15 pagesThe Surgical Treatment of Morton's NeuromaariearifinNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Jul 28, 2023Document6 pagesAdobe Scan Jul 28, 2023Krishna ChaurasiyaNo ratings yet

- Case Study PDFDocument4 pagesCase Study PDFania ojedaNo ratings yet

- Askep Klien Total Hip Replacement: Ns. Mulia Hakam, SP - Kep MBDocument55 pagesAskep Klien Total Hip Replacement: Ns. Mulia Hakam, SP - Kep MBfebriaNo ratings yet

- VAD Patient Education ManualDocument12 pagesVAD Patient Education ManualIakovos DanielosNo ratings yet

- HepatopatologiaDocument32 pagesHepatopatologiaCesar ArgoteNo ratings yet