Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Century of Cinema

Uploaded by

wernickemicaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Century of Cinema

Uploaded by

wernickemicaCopyright:

Available Formats

A Century of Cinema

Susan Sontag

Cinema's 100 years seem to have the shape of a life cycle: an

inevitable birth, the steady accumulation of glories and the onset

in the last decade of an ignominious, irreversible decline. It's not

that you can't look forward anymore to new films that you can

admire. But such films not only have to be exceptions -- that's

true of great achievements in any art. They have to be actual

violations of the norms and practices that now govern movie

making everywhere in the capitalist and would-be capitalist world

-- which is to say, everywhere. And ordinary films, films made

purely for entertainment (that is, commercial) purposes, are

astonishingly witless; the vast majority fail resoundingly to appeal

to their cynically targeted audiences. While the point of a great

film is now, more than ever, to be a one-of-a-kind achievement,

the commercial cinema has settled for a policy of bloated,

derivative film-making, a brazen combinatory or recombinatory

art, in the hope of reproducing past successes. Cinema, once

heralded as the art of the 20th century, seems now, as the century

closes numerically, to be a decadent art.

Perhaps it is not cinema that has ended but only cinephilia -- the

name of the very specific kind of love that cinema inspired. Each

art breeds its fanatics. The love that cinema inspired, however,

was special. It was born of the conviction that cinema was an art

unlike any other: quintessentially modern; distinctively

accessible; poetic and mysterious and erotic and moral -- all at the

same time. Cinema had apostles. (It was like religion.) Cinema

was a crusade. For cinephiles, the movies encapsulated

everything. Cinema was both the book of art and the book of life.

As many people have noted, the start of movie making a hundred

years ago was, conveniently, a double start. In roughly the year

1895, two kinds of films were made, two modes of what cinema

could be seemed to emerge: cinema as the transcription of real

unstaged life (the Lumiere brothers) and cinema as invention,

artifice, illusion, fantasy (Melies). But this is not a true

opposition. The whole point is that, for those first audiences, the

very transcription of the most banal reality -- the Lumiere

brothers filming "The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station" --

was a fantastic experience. Cinema began in wonder, the wonder

that reality can be transcribed with such immediacy. All of

cinema is an attempt to perpetuate and to reinvent that sense of

wonder.

Everything in cinema begins with that moment, 100 years ago,

when the train pulled into the station. People took movies into

themselves, just as the public cried out with excitement, actually

ducked, as the train seemed to move toward them. Until the

advent of television emptied the movie theaters, it was from a

weekly visit to the cinema that you learned (or tried to learn) how

to walk, to smoke, to kiss, to fight, to grieve. Movies gave you

tips about how to be attractive. Example: It looks good to wear a

raincoat even when it isn't raining. But whatever you took home

was only a part of the larger experience of submerging yourself in

lives that were not yours. The desire to lose yourself in other

people's lives . . . faces. This is a larger, more inclusive form of

desire embodied in the movie experience. Even more than what

you appropriated for yourself was the experience of surrender to,

of being transported by, what was on the screen. You wanted to

be kidnapped by the movie -- and to be kidnapped was to be

overwhelmed by the physical presence of the image. The

experience of "going to the movies" was part of it. To see a great

film only on television isn't to have really seen that film. It's not

only a question of the dimensions of the image: the disparity

between a larger-than-you image in the theater and the little

image on the box at home. The conditions of paying attention in a

domestic space are radically disrespectful of film. Now that a film

no longer has a standard size, home screens can be as big as living

room or bedroom walls. But you are still in a living room or a

bedroom. To be kidnapped, you have to be in a movie theater,

seated in the dark among anonymous strangers.

No amount of mourning will revive the vanished rituals -- erotic,

ruminative -- of the darkened theater. The reduction of cinema to

assaultive images, and the unprincipled manipulation of images

(faster and faster cutting) to make them more attention-grabbing,

has produced a disincarnated, lightweight cinema that doesn't

demand anyone's full attention. Images now appear in any size

and on a variety of surfaces: on a screen in a theater, on disco

walls and on megascreens hanging above sports arenas. The sheer

ubiquity of moving images has steadily undermined the standards

people once had both for cinema as art and for cinema as popular

entertainment.

In the first years there was, essentially, no difference between

these two forms. And all films of the silent era -- from the

masterpieces of Feuillade, D. W. Griffith, Dziga Vertov, Pabst,

Murnau and King Vidor to the most formula-ridden melodramas

and comedies -- are on a very high artistic level, compared with

most of what was to follow. With the coming of sound, the image

making lost much of its brilliance and poetry, and commercial

standards tightened. This way of making movies -- the Hollywood

system -- dominated film making for about 25 years (roughly

from 1930 to 1955). The most original directors, like Erich von

Stroheim and Orson Welles, were defeated by the system and

eventually went into artistic exile in Europe -- where more or less

the same quality-defeating system was now in place, with lower

budgets; only in France were a large number of superb films

produced throughout this period. Then, in the mid-1950's,

vanguard ideas took hold again, rooted in the idea of cinema as a

craft pioneered by the Italian films of the immediate postwar

period. A dazzling number of original, passionate films of the

highest seriousness got made.

It was at this specific moment in the 100-year history of cinema

that going to movies, thinking about movies, talking about movies

became a passion among university students and other young

people. You fell in love not just with actors but with cinema itself.

Cinephilia had first become visible in the 1950's in France: its

forum was the legendary film magazine Cahiers du Cinema

(followed by similarly fervent magazines in Germany, Italy, Great

Britain, Sweden, the United States and Canada). Its temples, as it

spread throughout Europe and the Americas, were the many

cinematheques and clubs specializing in films from the past and

directors' retrospectives that sprang up. The 1960's and early

1970's was the feverish age of movie-going, with the full-time

cinephile always hoping to find a seat as close as possible to the

big screen, ideally the third row center. "One can't live without

Rossellini," declares a character in Bertolucci's "Before the

Revolution" (1964) -- and means it.

For some 15 years there were new masterpieces every month.

How far away that era seems now. To be sure, there was always a

conflict between cinema as an industry and cinema as an art,

cinema as routine and cinema as experiment. But the conflict was

not such as to make impossible the making of wonderful films,

sometimes within and sometimes outside of mainstream cinema.

Now the balance has tipped decisively in favor of cinema as an

industry. The great cinema of the 1960's and 1970's has been

thoroughly repudiated. Already in the 1970's Hollywood was

plagiarizing and rendering banal the innovations in narrative

method and in the editing of successful new European and ever-

marginal independent American films. Then came the

catastrophic rise in production costs in the 1980's, which secured

the worldwide reimposition of industry standards of making and

distributing films on a far more coercive, this time truly global

scale. Soaring producton costs meant that a film had to make a lot

of money right away, in the first month of its release, if it was to

be profitable at all -- a trend that favored the blockbuster over the

low-budget film, although most blockbusters were flops and there

were always a few "small" films that surprised everyone by their

appeal. The theatrical release time of movies became shorter and

shorter (like the shelf life of books in bookstores); many movies

were designed to go directly into video. Movie theaters continued

to close -- many towns no longer have even one -- as movies

became, mainly, one of a variety of habit-forming home

entertainments.

In this country, [the U.S.] the lowering of expectations for quality

and the inflation of expectations for profit have made it virtually

impossible for artistically ambitious American directors, like

Francis Ford Coppola and Paul Schrader, to work at their best

level. Abroad, the result can be seen in the melancholy fate of

some of the greatest directors of the last decades. What place is

there today for a maverick like Hans- Jurgen Syberberg, who has

stopped making films altogether, or for the great Godard, who

now makes films about the history of film, on video? Consider

some other cases. The internationalizing of financing and

therefore of casts were disastrous for Andrei Tarkovsky in the last

two films of his stupendous (and tragically abbreviated) career.

And how will Aleksandr Sokurov find the money to go on

making his sublime films, under the rude conditions of Russian

capitalism?

Predictably, the love of cinema has waned. People still like going

to the movies, and some people still care about and expect

something special, necessary from a film. And wonderful films

are still being made: Mike Leigh's "Naked," Gianni Amelio's

"Lamerica," Fred Kelemen's "Fate." But you hardly find anymore,

at least among the young, the distinctive cinephilic love of movies

that is not simply love of but a certain taste in films (grounded in

a vast appetite for seeing and reseeing as much as possible of

cinema's glorious past). Cinephilia itself has come under attack,

as something quaint, outmoded, snobbish. For cinephilia implies

that films are unique, unrepeatable, magic experiences. Cinephilia

tells us that the Hollywood remake of Godard's "Breathless"

cannot be as good as the original. Cinephilia has no role in the era

of hyperindustrial films. For cinephilia cannot help, by the very

range and eclecticism of its passions, from sponsoring the idea of

the film as, first of all, a poetic object; and cannot help from

inciting those outside the movie industry, like painters and

writers, to want to make films, too. It is precisely this notion that

has been defeated.

If cinephilia is dead, then movies are dead too . . . no matter how

many movies, even very good ones, go on being made. If cinema

can be resurrected, it will only be through the birth of a new kind

of cine-love.

This is an abridged version of an essay originally written for the

Frankfurter Rundschau in 1995. For a more recent and very

interesting article by Susan Sontag about the war in Iraq, see

Regarding the Torture of others

You might also like

- A Century of Cinema Susan SontagDocument4 pagesA Century of Cinema Susan SontagAkbar HassanNo ratings yet

- Sontag Cinema Century DeclineDocument4 pagesSontag Cinema Century DeclineWeiling GanNo ratings yet

- Susan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFDocument4 pagesSusan Sontag The Decay of Cinema PDFabenasayagNo ratings yet

- The Decay of CinemaDocument4 pagesThe Decay of CinemaBill VassiliosNo ratings yet

- Charlie Kaufman and Hollywood's Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers: An Excursion Into the American New WaveFrom EverandCharlie Kaufman and Hollywood's Merry Band of Pranksters, Fabulists and Dreamers: An Excursion Into the American New WaveNo ratings yet

- A Century of Cinema - Susan SontagDocument4 pagesA Century of Cinema - Susan Sontagcrisie100% (2)

- Reinventing Cinema for the Digital AgeDocument12 pagesReinventing Cinema for the Digital Agetrenino222No ratings yet

- Sound in Film - The Change from Silent Film to the TalkiesFrom EverandSound in Film - The Change from Silent Film to the TalkiesNo ratings yet

- Il MaestroDocument9 pagesIl MaestrosatanasvobiscumNo ratings yet

- Cahiers - Du - Cinema - 1960-1968 - 31 Jean-Luc GodardDocument6 pagesCahiers - Du - Cinema - 1960-1968 - 31 Jean-Luc GodardXUNo ratings yet

- Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and Its Legacies, From Nickelodeons to YoutubeFrom EverandChain of Fools: Silent Comedy and Its Legacies, From Nickelodeons to YoutubeNo ratings yet

- Toward A Re-Invention of CinemaDocument16 pagesToward A Re-Invention of Cinemacolin capersNo ratings yet

- Cult Filmmakers: 50 Movie Mavericks You Need to KnowFrom EverandCult Filmmakers: 50 Movie Mavericks You Need to KnowRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Film Genres and MovementsDocument4 pagesFilm Genres and MovementsSameera WeerasekaraNo ratings yet

- Escape From Alcatraz - Introductory Notes To The Cinema (2005)Document11 pagesEscape From Alcatraz - Introductory Notes To The Cinema (2005)ruediediNo ratings yet

- Film Culture on Film Art: Interviews and Statements, 1955-1971From EverandFilm Culture on Film Art: Interviews and Statements, 1955-1971No ratings yet

- François Truffaut and La Nouvelle VagueDocument8 pagesFrançois Truffaut and La Nouvelle Vagueveralynn35No ratings yet

- Dark History of Hollywood: A century of greed, corruption and scandal behind the moviesFrom EverandDark History of Hollywood: A century of greed, corruption and scandal behind the moviesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (11)

- Putting the Show OverDocument12 pagesPutting the Show Overxwqj6dzrb5No ratings yet

- Mohamed Jimale - Year 12 Booklet Studying Silent CinemaDocument18 pagesMohamed Jimale - Year 12 Booklet Studying Silent CinemaMohamed JimaleNo ratings yet

- Hollywood CinemaDocument28 pagesHollywood CinemaPasty100% (1)

- Luz, cámara y la historia del cineDocument9 pagesLuz, cámara y la historia del cineJulio Cesar Mamani VillcaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of The Comic Book MovieDocument3 pagesThe Rise of The Comic Book MovielaurenliddelNo ratings yet

- European Cinema and American Movies - ArticleDocument3 pagesEuropean Cinema and American Movies - ArticleZsuzsanna TorokNo ratings yet

- Gunning - Cinema of AttractionDocument8 pagesGunning - Cinema of AttractionMarcia Tiemy Morita Kawamoto100% (2)

- Noel Burch "A Primitive Mode of Representation?" and Motionless VoyageDocument25 pagesNoel Burch "A Primitive Mode of Representation?" and Motionless VoyageMike MetzgerNo ratings yet

- A Decade Under The InfluenceDocument3 pagesA Decade Under The InfluenceNilson AlvarengaNo ratings yet

- Kent JonesDocument7 pagesKent Jonesyahooyahooyahoo1126No ratings yet

- W2 (9.20) Preclassical Film HistoryDocument15 pagesW2 (9.20) Preclassical Film Historykm5653No ratings yet

- Sample Stateofamericanfilm JohnrkitchDocument3 pagesSample Stateofamericanfilm Johnrkitchapi-279494198No ratings yet

- French Filmmakers on FilmmakingDocument204 pagesFrench Filmmakers on FilmmakingFabián UlloaNo ratings yet

- History of The Cinema in The UDocument3 pagesHistory of The Cinema in The UchloemuisukNo ratings yet

- Cinema History in 40 CharactersDocument29 pagesCinema History in 40 CharactersJosephine EnecuelaNo ratings yet

- The American Silver Screen Atestat EnglezaDocument21 pagesThe American Silver Screen Atestat EnglezaDenisa DnxNo ratings yet

- Jumping The SharkDocument5 pagesJumping The Sharkapi-336569481No ratings yet

- Review of Books on French and Italian Film HistoryDocument3 pagesReview of Books on French and Italian Film HistoryJames Gildardo CuasmayànNo ratings yet

- Cópia de Written WorkDocument4 pagesCópia de Written WorkAna Rita ValenteNo ratings yet

- Cinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewDocument1 pageCinema & Culture - by Dudley AndrewOuahab HamzaNo ratings yet

- Leacock - For An Uncontrolled CinemaDocument2 pagesLeacock - For An Uncontrolled Cinemaalval87No ratings yet

- Hans Richter - The Film As An Original Art Form (1951)Document6 pagesHans Richter - The Film As An Original Art Form (1951)Tiko MamedovaNo ratings yet

- Thomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentDocument17 pagesThomas - Elsaesser - Cinephilia or The Uses of DisenchantmentLuisa FrazãoNo ratings yet

- John Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Document312 pagesJohn Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Andreea Cristina BortunNo ratings yet

- Cinematography Video Essay ScriptDocument9 pagesCinematography Video Essay Scriptapi-480303503100% (1)

- CinemaDocument2 pagesCinemarapikil324No ratings yet

- Art - The History of CinemaDocument29 pagesArt - The History of CinemaAlloySebastinNo ratings yet

- Cinematography Theory III Final Essay: The Embrace of the Serpent and Its Broken TaleDocument4 pagesCinematography Theory III Final Essay: The Embrace of the Serpent and Its Broken TaleCarlos CastañedaNo ratings yet

- EVOLUTION OF EXHIBITION METHODS OF CINEMADocument2 pagesEVOLUTION OF EXHIBITION METHODS OF CINEMAryb2v9b6nrNo ratings yet

- Film Film Frexh WaveDocument5 pagesFilm Film Frexh WaveRashiNo ratings yet

- Cinema and ModernismDocument7 pagesCinema and ModernismlexsaugustNo ratings yet

- The Power of The Big Screen PDFDocument5 pagesThe Power of The Big Screen PDFNizam UddinNo ratings yet

- FrenchtoamericannewwaveDocument11 pagesFrenchtoamericannewwaveapi-286011720No ratings yet

- Unpaid Unclaimed Final Dividend Account FY 2016 17Document360 pagesUnpaid Unclaimed Final Dividend Account FY 2016 17ROHIT THAKURNo ratings yet

- Verb Form E7 (Unit 7-12)Document11 pagesVerb Form E7 (Unit 7-12)Nguyễn Hương LyNo ratings yet

- Contact List 251017Document2 pagesContact List 251017Saurabh Patel50% (2)

- RDX MovieDocument6 pagesRDX Movieabhayb22429No ratings yet

- All Courts Direct URL Links - 10Document5 pagesAll Courts Direct URL Links - 10Tarini VardhanNo ratings yet

- SeniorityDocument275 pagesSeniorityRajanala Vignesh NaiduNo ratings yet

- A. Vocabulary: Unit 2: Going To The MoviesDocument5 pagesA. Vocabulary: Unit 2: Going To The MoviesTran Minh Cuong (FPL HCMK16)No ratings yet

- EMAM Members ListDocument16 pagesEMAM Members Listrita pandita0% (1)

- ĐỀ THI TUYỂN SINH LỚP 10 TRUNG HỌC PHỔ THÔNGDocument5 pagesĐỀ THI TUYỂN SINH LỚP 10 TRUNG HỌC PHỔ THÔNGHà TrangNo ratings yet

- Choti Behan Ki Jabardast Chudai - Indian Sex StoryDocument58 pagesChoti Behan Ki Jabardast Chudai - Indian Sex Storyshumail usman62% (13)

- Letterboxd 2023 Oscar BallotDocument1 pageLetterboxd 2023 Oscar BallotMaria Ines MoyanoNo ratings yet

- SJKT Ladang Tangkah, Tangkak Senarai Nama Penerima Bantuan Awal Persekolahan 2020 BIL Nama Gaji Per Kapita (RM) LulusDocument1 pageSJKT Ladang Tangkah, Tangkak Senarai Nama Penerima Bantuan Awal Persekolahan 2020 BIL Nama Gaji Per Kapita (RM) LulusAnonymous 1o1M4oeR0UNo ratings yet

- Contact details of PHED officersDocument11 pagesContact details of PHED officersprabhjot260% (1)

- Political Representation of FilmsDocument6 pagesPolitical Representation of FilmsPranay KekanNo ratings yet

- Buying House - DetailsDocument12 pagesBuying House - DetailsankurmakhijaNo ratings yet

- The Legend of Ashitaka: Joe Hisaishi Arr. Mario CiaccoDocument2 pagesThe Legend of Ashitaka: Joe Hisaishi Arr. Mario CiaccoMario CiaccoNo ratings yet

- Shukran Allah Mere Maula: Kasam Ki KasamDocument4 pagesShukran Allah Mere Maula: Kasam Ki KasamreemasshahNo ratings yet

- Citizen KaneDocument2 pagesCitizen KaneСнежана ДемченкоNo ratings yet

- Email Id Delhi1 StudentsDocument16 pagesEmail Id Delhi1 StudentsSuresh G KNo ratings yet

- Am PB RTM b2 Reading U8Document4 pagesAm PB RTM b2 Reading U8huyennhuyen123No ratings yet

- Srirupa Roy - Moving Pictures: The Postcolonial State and Visual Representations of IndiaDocument31 pagesSrirupa Roy - Moving Pictures: The Postcolonial State and Visual Representations of IndiaSudipto BasuNo ratings yet

- Best 50 Tips For ALADDIN 1992 FULL HD MOVIEDocument2 pagesBest 50 Tips For ALADDIN 1992 FULL HD MOVIEMd nobab HasanNo ratings yet

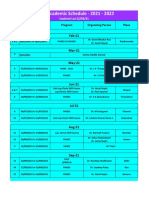

- IAGES Academic Schedule 2021Document2 pagesIAGES Academic Schedule 2021Razor GGNo ratings yet

- List of GT ProvisionalDocument29 pagesList of GT ProvisionalEr Abhi SinghNo ratings yet

- Let Me Introduce Myself (Zahira Inayah P HRP)Document1 pageLet Me Introduce Myself (Zahira Inayah P HRP)muthia hrpNo ratings yet

- Seniority List as per SAPDocument2 pagesSeniority List as per SAPswamy ChinthalaNo ratings yet

- Thomas Wishart - Edward Scissorhands Teel ParagraphDocument1 pageThomas Wishart - Edward Scissorhands Teel Paragraphapi-526201635No ratings yet

- Https/nclat Nic In/sites/default/files/2023-06/08 06 2023 PDFDocument5 pagesHttps/nclat Nic In/sites/default/files/2023-06/08 06 2023 PDFPrakash VenkataramaniNo ratings yet

- Arthur Jafa: Human, AlienDocument12 pagesArthur Jafa: Human, AlienAleksandarBitola100% (1)

- Siti New Pack 2023Document10 pagesSiti New Pack 2023madhurajatsbengNo ratings yet