Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dich KTXĐGHH

Uploaded by

letandat14122003Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dich KTXĐGHH

Uploaded by

letandat14122003Copyright:

Available Formats

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

W25637

BDP INTERNATIONAL: DELIVERING WHAT MATTERS IN GLOBAL

CHEMICAL TRANSPORTATION

Neha Mittal wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate either effective or

ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The author may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to

protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the

permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights

organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western

University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com. Our goal is to publish

materials of the highest quality; submit any errata to publishcases@ivey.ca. i1v2e5y5pubs

Copyright © 2022, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2022-01-27

The first quarter of 2021 had just ended, and April 2021 was the start of a new and busy season for the maritime

shipping industry. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic had increased demand in the global marketplace, which

strained carrier capacity and caused freight rates to surge. Amid the tough trade conditions, Michael Ford, the

vice-president of Government and Industry Affairs at BDP International Inc. (BDP), along with Angela Davis,

the director of Transportation at BDP, were working in their Philadelphia office on a key account that required

an export shipment of fifteen containers per month, for a year. These containers carried a chemical used for

coatings in the electronics industry and were labelled as dangerous goods.

The status of the dangerous goods required Ford and Davis to carefully balance available modal and carrier

choices, transit time, cost, and available capacities. The planning was not easy, and when they thought they

had chosen the optimal route and carrier and had processed all required documentation for their client,

ConCoat Chemicals, a fire erupted on one of the vessels during its voyage and destroyed a few of the

customer’s containers. This emergency required the BDP team to use their expertise and devise a way to

not only inform their customer ConCoat as well as the buyer of the products, but also address the incomplete

shipment order.

EVOLUTION OF BDP INTERNATIONAL

BDP was one of the world’s leading privately-held, non-asset-based freight logistics companies, based in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its origins traced to 1966, when Richard J. Bolte Sr. formed the R.J. Bolte

Company in Philadelphia. Through a series of mergers, the company became BDP International in 1972.1

A single father, Bolte Sr. started BDP with a typewriter and a $1,200 loan, and grew the company into a

global business. He was an early adopter of information technology for managing and organizing

international freight movements and other aspects of global shippers’ supply chains. In the following half-

century, he grew the business into a network of wholly owned operations, joint ventures, and affiliates in

1

BDP International, “Global Logistics Leader BDP International Celebrates 50th Anniversary,” August 19, 2016,

https://www.bdpinternational.com/news/global-logistics-leader-bdp-international-celebrates-50th-anniversary.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 2 W25637

nearly 140 countries, with over 270 offices across the world and more than 4,400 employees. The company

was later led by Richard J. Bolte Jr., who kept BDP as a family-owned business. Having worked for BDP

since age fifteen, Bolte Jr. knew he was interested in pursuing a career in logistics, so he studied business

and finance while at university. Upon graduating in 1979, Bolte Jr. returned home to work at BDP’s

Philadelphia office, where he was the company’s twenty-fifth employee. He helped BDP flourish into a

global leader in transportation (by 2021, it employed more than 4,500 employees), import/export,

warehousing and distribution, trade, security and environmental regulatory compliance, process

improvement, and global logistics modelling and management.2

After fifty years in service, BDP’s annual global net revenue was reported at over US$2 billion3 in 2017, with

200,000 monthly transactions.4 BDP’s value proposition was built on best-in-class processes, global presence,

client-driven systems, flawless tactical execution, and a nimble, small-company customer service culture.

BDP’S RANGE OF SERVICES

BDP provided a range of services, such as ocean, air, and ground transportation; export freight forwarding;

import customs clearance and regulatory compliance; and its web-based BDP Smart Suite® of shipping

transaction and tracking management and visibility applications. It had over 4,000 clients worldwide,

including chemical companies, industrial and manufacturing firms, life sciences and health care, and retail

and consumer. BDP was a leading fourth-party logistics (4PL) company; it assumed many of the same roles

supporting shipping operations as third-party logistics (3PL) providers but with much broader responsibility

and accountability to help clients reach strategic goals. BDP had built expertise in analytics and

optimization, regulatory compliance, trade compliance management, export and import facilitation, and

warehousing and distribution.

BDP took pride in calling itself “chemical experts.” Sixty-five per cent of its business served the chemical

industry and eight of the world’s top ten chemical companies called BDP a preferred provider. According to

the company, as of 2020 it handled 1.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs)5 of chemicals and 55

million kilograms of air freight chemicals on an annual basis.6 BDP built its internal operating practices and

information systems to handle the unique logistics requirements of chemical-related shipments. It provided

training and information for clients and employees about hazardous materials safety and environmental and

security compliance regulations. The company had thrice received the Responsible Care® Partner of the Year

Award from the American Chemistry Council. The Responsible Care awards program was the chemical

industry’s health, safety, and environmental performance improvement initiative and was recognized as one

of the most successful initiatives advanced by the industry since being launched in 1988.7

2

Kelly Flynn, “Like Father, Like Son: Bolte Working to Preserve Three Legacies,” The Sun Newspapers, July 23, 2018,

https://thesunpapers.com/2018/07/23/like-father-like-son-bolte-working-to-preserve-three-legacies.

3

All dollar amounts are in US dollars.

4

BDP International, BDP International, accessed July 7, 2021,

https://www.bdpinternational.com/uploads/attachments/cj9hepr4l02e49xqpemxt61ht-bdp-at-a-glance-english.pdf.

5

TEUs were a unit of measurement to determine cargo capacity for container ships and terminals, derived from the dimensions

of a 20-foot standardized shipping container.

6

BDP International, Chemical Logistics, 2020, https://www.bdpinternational.com/uploads/attachments/ck805m0clxdxlksqpvow9bxgs-

bdp-chemical-brochure-2020.pdf.

7

BDP International, Shipping Safely and Responsibly, accessed November 29, 2021, https://www.bdpinternational.com/who-

we-are/environmental-social-governance/responsible-care.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 3 W25637

CHEMICAL SHIPPING: THE HAZMAT INDUSTRY

Hazardous materials (hazmat) were substances that posed a risk to property, health, and safety of the public

when misused or involved in an accident. Hazmat products could be poisonous, explosive, corrosive,

flammable, or radioactive, and they varied in shape, size, and utility. Daily household objects such as

batteries, products ranging from paints to medical supplies, and acidic chemicals all fell under hazmat. They

required careful handling for the sake of public and environmental safety. Proper handling involved special

packaging, clear marking, placards, and accurate paperwork identifying all hazardous goods.

The chemical supply chain was a highly complex business and required skilled personnel for the

manufacturing, handling, and transportation of hazardous goods. Chemical logistics companies were

responsible for safely transporting and storing these potentially dangerous products, and they typically

offered global transportation services by sea and, when required urgently, air freight services for bulk

commodities and raw materials.

According to a report by Grand View Research Inc., the size of the global chemical tanker shipping market

was anticipated to reach $2.5 trillion by 2025.8 The triggers for expected growth in the global trade for

chemicals and derivatives were rising manufacturing activities and disparity in regional production (thus

necessitating shipment of materials for manufacturing).

The United Nations Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods classified dangerous goods

by nine categories.9 The level of risk and type of reaction associated with dangerous and hazardous

substances varied according to the class division and properties of the substance. The quantity, location,

and properties of other materials within the vicinity also played an important role in determining the level

of risk associated with a substance.

Shipping dangerous goods internationally by vessel was regulated through the International Maritime

Organization (IMO), a specialized agency of the United Nations. The IMO used the International Maritime

Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code—a global, international reference adopted in 1965—to regulate shipping

dangerous goods by maritime vessel. These regulations were updated every two years, with each

amendment valid for three years. The IMDG Code, 40th Amendment, was released in 2020. It included

detailed recommendations for individual substances, materials, and articles; standard requirements for all

aspects of handling dangerous goods and marine pollutants in sea transport; and recommendations for good

operational practice, including advice on terminology, packing, labelling, storage, separation, and handling

emergency response action. The recommendations and advice applied to manufacturers, packers, shippers,

feeder services such as road and rail, port authorities, and mariners.10

SHIPPING REQUIREMENTS OF CONCOAT CHEMICALS

ConCoat Chemicals manufactured conformal coating material used in the electronics industry. It operated

in a highly competitive market and demanded high-quality service and resourceful solutions from its

logistics service provider so the company could focus on its core competencies. Knowing BDP’s

capabilities, ConCoat Chemicals reached out to Ford in April 2021 to request that BDP meet one of its

shipping requirements. Ford asked Davis to work on the assignment with him, and he assured ConCoat

8

Grand View Research, “Chemical Tanker Shipping Market Size Worth $2.50 Trillion by 2025,” November 2017,

https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-chemical-tanker-shipping-market.

9

United Nations, Part 2: Classification, 2009, https://unece.org/DAM/trans/danger/publi/unrec/rev16/English/02E_Part2.pdf.

10

“The IMDG Code—IMO Dangerous Goods Regulations,” Label Master, accessed July 7, 2021,

https://www.labelmaster.com/imdg-code.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 4 W25637

Chemicals, a key account for BDP, that he would take the utmost care to plan for a safe and timely delivery

of its containers.

ConCoat Chemicals had two separate shipping requirements. For the first requirement, it needed to ship 10

TEUs each month for a year. Shipments were to originate in Baltimore, Maryland, destined for the port of

Shanghai, China. The consignee was A-One Wiring, who was a new client for ConCoat Chemicals. The

commodity was a chemical used in the electronic industry for coatings, which carried a dangerous goods

label. BDP was to select the routing and carrier to China.

The second requirement was to ship 5 TEUs per month for a year. Again, the shipments would originate in

Baltimore, Maryland, but these shipments were destined for Antwerp, Belgium. The commodity for these

shipments was also a chemical used in the electronic industry for coatings, which carried a dangerous goods

label, but the consignee was SineChem, who was an existing client for ConCoat Chemicals.

BDP was tasked to select the right routing and water carrier for the freight orders. Ford and Davis needed

the optimal shipping plan (route and carrier) to ensure a timely and economical delivery of ConCoat

Chemicals’ containers.

CHOOSING THE SHIPPING PLAN

Route Choice

BDP had two route choices for ConCoat Chemicals’ shipping order to Shanghai, China. The containers

could be shipped using an all water service (AWS) from Baltimore, Maryland, or they could be sent by a

mini land bridge (MLB), transported first by truck or train to the ports of Los Angeles or Long Beach,

California, and then by water to their final destination in China (see Exhibit 1).

With AWS, cargo ships sailed from their point of origin to their destination using only water routes.

Historically, AWS was considered a cost-effective and environmentally friendly way to ship cargo, but

with the need for quick deliveries in recent years, AWS was found to be slower than other intermodal freight

transport options. AWS routes for ConCoat Chemicals’ shipments to Shanghai could go across the Pacific

Ocean or they could travel the Atlantic Ocean by going through the Suez Canal (see Exhibit 2).

If BDP elected to use the MLB, the shipments would use an intermodal freight service, using truck or rail

to transport the goods in their shipping containers to a port, and then an ocean vessel to ship the goods in

their shipping containers to the destination port in their shipping containers to the destination port (see

Exhibit 3). For the last few decades, the North American land bridge had provided a straightforward and

effective solution for cargo bound to and from Asia. Even though AWS had its advantages, the North

American land bridge saved time, taking the least travel time between the two trade regions. For instance,

a container shipped AWS between New York and Singapore would take thirty days by way of the Panama

Canal but would take only nineteen days if the MLB was used with double-stacked rail transport.11

Another advantage to the MLB was that the average number of containers moved for each vessel that called

into port (average call size) in Los Angeles or Long Beach was much higher—about 8,000 to 12,000

containers per call—as compared to only 2,500 to 4,500 container moves per vessel call on the East Coast

11

Jean-Paul Rodrigue, “The North American Landbridge,” Geography of Transport Systems, 2020,

https://transportgeography.org/contents/applications/transcontinental-bridges/north-america-landbridge.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 5 W25637

ports.12 However, since the summer of 2020, West Coast ports had been burdened by issues with vessel

bunching (when vessels arrived within a short amount of time between each other, causing port congestion,

delays, and disruption in the supply chain) and delays in berthing (ships were anchored offshore waiting to

berth and unload), congested marine terminals, long truck lines at terminal gates, and shortages of chassis

on to which to load the containers for land transport because so many were in use with the trucks sitting

idle waiting to unload.13

The cargo surge that had exploded at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach continued into the new year.

Cargo numbers at the port of Los Angeles were up by 3.6 per cent in January 2021 compared to the same

month a year earlier, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the port of Long Beach had a nearly 22

per cent jump, making the month its busiest January on record.14 Reports from both ports indicated that the

surge would likely continue in the months ahead. Both Los Angeles and Long Beach had a backlog of ships

either in port or at anchor waiting to pull into port.15

On the East Coast ports, things were not very different. In November 2020, East Coast ports were

challenged in handling a year-over-year 30 per cent increase in imports from Asia.16 Mounting container

dwell times at marine terminals and chassis dwell times at warehouses were reported across the US East

Coast. The gains were prompting concerns among drayage17 providers that a chassis shortage could also be

imminent if cargo owners could not unload containers fast enough.

These trade conditions and the demand–supply imbalance left Ford and Davis with a decision-making

problem: should they ship ConCoat Chemicals’ containers over water directly from the East Coast to

Shanghai or should they use the MLB? Thankfully, the route decision for shipping containers to Belgium

was relatively straightforward, although Ford and Davis needed to pay attention to delivery times and costs.

Carrier Selection

After choosing the route (AWS or MLB), BDP needed to determine which water carriers to use for ConCoat

Chemicals’ container shipments.

BDP reviewed various factors, such as the carriers’ financial stability, geographical coverage, reliability

(on-time pickup and delivery), technical capabilities, ability to share information, and experience with

freight damage, and then narrowed the choice to four carriers (see Exhibit 4). But Ford and Davis still

needed to consider the cost, transit time between origin and destination, and equipment availability of these

four carriers. They knew that if the goods did not arrive within the tolerance limit of plus or minus five–

seven days, the shipper would be assessed an additional penalty for late delivery, which was 1 per cent of

the invoice value at five–seven days late and 3 per cent of the invoice value beyond the seven-day timeline.

12

Bill Mongelluzzo, “Increasing Vessel Sizes a Red Flag for US Ports,” Journal of Commerce, December 21, 2020,

https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/container-lines/increasing-vessel-sizes-red-flag-us-ports_20201221.html.

13

Veronica Nigh and Daniel Munch, “Congestion at West Coast Seaports Hinders Trade Boom,” Market Intel (blog for

American Farm Bureau Federation), June 9, 2021, https://www.fb.org/market-intel/congestion-at-west-coast-seaports-

hinders-trade-boom.

14

Donna Littlejohn, “Cargo Surge Shows No Sign of Letting up in Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach,” Daily Breeze,

February 17, 2021, https://www.dailybreeze.com/2021/02/17/cargo-surge-shows-no-sign-of-letting-up-in-ports-of-los-

angeles-and-long-beach.

15

“Backlog of Cargo Ships at Southern California Ports Reaches an All-Time High,” The Guardian, October 20, 2021,

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/oct/20/supply-chain-crisis-california-ports-cargo-ships.

16

Bill Mongelluzzo, “US East Coast Ports Avoid Gridlock Despite Rising Volumes,” Journal of Commerce, December 16, 2020,

https://www.joc.com/port-news/us-ports/us-east-coast-ports-avoid-gridlock-despite-rising-volumes_20201216.html.

17

Drayage is short-distance transportation of goods.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 6 W25637

Ford and Davis needed to rank their shortlist of four carriers and decide whether one carrier could handle

all the shipments or if BDP would need to book separate carriers for each of ConCoat Chemicals’ two

requirements.

RISKS WITH GLOBAL TRANSPORTATION

When goods were sent overseas, they became vulnerable to sea threats. Irrespective of how well the

transportation was planned, uncertainties existed in global transportation, and the risks increased when

containers were labelled “dangerous goods.” Traditionally, common cargo shipping risks included natural

disasters, mechanical failures, and human error. However, with the rapid growth of international trade and

the introduction of new technologies, newer risks had been introduced.

The common risks in maritime transportation were extensive. Weather was a significant concern, with

weather catastrophes such as hurricanes, large waves, and high winds having hurt the cargo shipping

industry’s supply chain model for ages. It was not uncommon for natural weather events to cause cargo

ships to lose some, or all, of the cargo on board.

Cyber risks were another concern. Most computer systems aboard cargo ships were self-contained, but they

were still vulnerable to insider threats, such as human error or disgruntled employees with conflicting

motives. With some computer systems needing to be connected outside the ship, hacks from the outside

were also possible, which could steer the ship off course.

Piracy, typically thought of as an historical problem, was, in fact, still very much a modern problem. Several

cargo shipping thefts were closely linked with piracy at sea. Human error was also, and always, a risk.

Shipments on international cargo ships were found mislabelled, improperly handled, or carrying other

safety risks. This could result in onboard fires and containers falling off the ship.18

Container Ship Fires

Ship fire was one of the most widely reported risks when carrying dangerous goods onboard a vessel. Since

2010, there had been substantial increases in the number of fires in containers carried onboard container

ships and roll-on/roll-off (ro-ro) ships, which carried wheeled cargo driven on and off the ship. Major fires

on container vessels were becoming one of the largest hazards for the global shipping industry. According

to an article published in April 2021, there was, on average, a fire onboard a container ship every week,

with a major container fire occurring on average every sixty days.19

Despite IMO requirements that shippers must declare container contents, there were a growing number of

instances where cargo was not being properly declared. The increasing volume of containers on a ship also

increased the likelihood of transporting dangerous goods that might ignite or explode on board. A survey

reported by Campbell Johnston Clark in 2020 found that about 10 per cent of laden containers, or 5.4 million

containers, contained declared dangerous goods. Of those, about 1.3 million were poorly packed or

18

Costas Paris, “Spate of Fires Has Shipping Industry Looking at How Dangerous Goods Are Handled,” The Wall Street

Journal, November 24, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/spate-of-fires-has-shipping-industry-looking-at-how-dangerous-

goods-are-handled-11574600400.

19

Andrew Gray, “Top Maritime Trends of 2020: Tackling the Scourge of Containership Fires,” Marine Link, December 9, 2020,

https://www.marinelink.com/news/top-maritime-trends-tackling-scourge-483775.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 7 W25637

incorrectly identified, indicating the scale of potential risk.20 Dangerous goods cargo that was incorrectly

secured could shift during the voyage, generating heat from friction and leading to a fire. Additionally, due

to the distance out to sea, volumes, stack heights, and lack of access and reach, once a fire ignited the

potential for damage and the challenges with firefighting were significant.

Both those in the supply chain and those working with the on-board firefighting systems were attempting

to deal with this problem. To contain financial risk, shippers purchased an insurance policy before shipping

the cargo to cover for uncertainty and risks involved in shipping overseas. Ship owners declared a “general

average” if their ships and cargo suffered damage or delay. This contractual obligation required cargo

owners to shoulder part of the loss, based on the value of their cargo and its percentage share of the total

value of the ship plus all cargo on board, called the “value of voyage.”

BDP’S CRISIS

In April 2021, Ford and Davis booked their client’s order for the shipping requirements destined for both

China and Belgium. They had meticulously considered all the requirements and shipping options, and

everything seemed right. The vessel for Belgium was on time and arrived as scheduled at the port of loading

in Baltimore. All five containers were loaded on board and the vessel sailed to the next port of call in

Savannah, Georgia. Shipping documentations were processed on behalf of ConCoat Chemicals, and the

ocean bill of lading21 and commercial invoice were sent to the final client in Belgium so that it could begin

to clear the goods through Belgian customs.

Everything was going according to plan until the ship caught fire while crossing the Atlantic Ocean,

damaging some of the containers on board. Ford and Davis were immediately informed of the incident, but

the name of the consignee, exact number of containers affected by the fire, and the contents of the containers

remained unknown at that time. After twenty-four hours, some details emerged and BDP’s team was

informed that three of its client’s containers had been engulfed by the fire and were damaged beyond use.

The entire value of the containers was lost.

THE DECISION

Based on the DI Chemical’s requirements, how should Ford and Davis (1) implement an optimal shipping

plan (route and carrier) to ensure a timely and economical delivery of the containers, and how should Ford

and Davis handle the incident with the onboard fire, address the partial delivery of the client’s order, and

make whole on the order after the fire had damaged a few of the client’s containers beyond use?

Now Ford and Davis needed to handle the incident with the onboard fire. How would they address the

partial delivery of the client’s order and make whole on the order after the fire had damaged a few of the

client’s containers beyond use?

20

Andrew Gray, “Tackling the Scourge of Container Ship Fires,” Campbell Johnston Clark, October 22, 2020,

https://www.cjclaw.com/site/news/tackling-the-scourge-of-container-ship-fires.

21

Bill of Lading refers to a detailed list of a shipment of goods in the form of a receipt given by the carrier to the person

consigning the goods.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 8 W25637

EXHIBIT 1: LAND BRIDGE, MINI LAND BRIDGE, AND MICRO BRIDGE IN NORTH AMERICA

A land bridge is a connection between two maritime segments over a land mass. It is a multi-modal transport

option in which containerized cargo is first sent to a port on one coast, unloaded to ground transport (truck

or train) to be moved to a port on another coast, and then again loaded on to another water vessel to reach

its final destination. The North American land bridge represents the most efficient land bridge in the world,

which considerably reduces distances between the East and the West Coasts of the United States. The

North American land bridge is mainly the outcome of growing transpacific trade, with goods from China

being sent to consumers in Europe and the United States.

Three are three major types of land bridges:

A land bridge is a link between a foreign origin and a destination. The continental mass is used as a link

(bridge) between two maritime systems. The transport mode in most cases is rail because it offers a faster

long-distance service. For example, using the North American land bridge to ship a container from China

or Japan to Europe bypasses the detour imposed by the Panama Canal.

A mini land bridge involves a foreign origin but a destination that is at the end of the landmass of the port

of entry. For example, containers from the Far East may arrive on the West Coast of North America and be

shipped by rail to a final destination on the East Coast, such as New York.

A micro land bridge involves a foreign origin and a landmass that is used as a link from the port of entry

to an inland destination. For example, containers from the Far East may arrive on the West Coast of North

America and then be shipped by rail or truck to an inland destination such as Chicago or Houston.

Source: Created by the case author based on Jean-Paul Rodrigue, “Types of Landbridges,” Geography of Transport Systems,

2020, https://transportgeography.org/contents/applications/transcontinental-bridges/types-landbridges.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 9 W25637

EXHIBIT 2: OCEAN ROUTE DISTANCES BETWEEN SHANGHAI AND NEW YORK

Note: km = kilometres.

Source: Created by the case author.

EXHIBIT 3: ALL WATER SERVICE AND MINI LAND BRIDGE ROUTE CHOICES TO CHINA

Cost per TEU

Origin Destination Via Distance Transit Time

(China bound)

Panama Canal

Baltimore Shanghai 19,500 km 24 days US$1,646

(AWS)

Cape Horn

Baltimore Shanghai 30,500 km 37 days US$1,690

(AWS)

Suez Canal

Baltimore Shanghai 26,000 km 28 days US$1,559

(AWS)

Mini Land Bridge 19 days via port

Baltimore Shanghai 14,500 km US$2,725

(MLB) of LA/LB

Note: AWS = all water service; LA = Los Angeles; LB = Long Beach; MLB = mini land bridge; TEU = twenty-foot equivalent

units; km = kilometres.

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

For the exclusive use of T. Nguyen, 2023.

Page 10 W25637

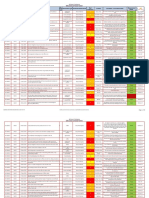

EXHIBIT 4: CARRIER CHOICES

Carrier A Carrier B

• Allocation: 12 × TEUs per sailing • Allocation: 8 × TEUs per sailing

• Rate to Antwerp: US$1,137.00 (per TEU) • Rate to Antwerp: US$1,483.00 (per TEU)

• Rate to Shanghai: US$1,690.00 (per TEU) • Rate to Shanghai: US$1,646.00 (per TEU)

• Transit time to Antwerp: 18 days • Transit time to Antwerp: 15 days

• Transit time to Shanghai: 38 days • Transit to Shanghai: 24 days

Carrier C Carrier D

• Allocation: 14 × TEUs per sailing • Allocation: 10 × TEUs per sailing

• Rate to Antwerp: US$1,516.00 (per TEU) • Rate to Antwerp: US$1,200.00 (per TEU)

• Rate to Shanghai: US$1,559.00 (per TEU) • Rate to Shanghai: US$2,725.00 (per TEU)

• Transit time to Antwerp: 11 days • Transit time to Antwerp: 20 days

• Transit time to Shanghai: 28 days • Transit time to Shanghai: 19 days MLB

Note: MLB = mini land bridge; TEU = twenty-foot equivalent units.

Source: Company documents.

This document is authorized for use only by Thai Nguyen in 2023.

You might also like

- Pacific Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map 2021–2025From EverandPacific Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map 2021–2025No ratings yet

- Case Study ON Transportation &logistics Dubai Ports WorldDocument6 pagesCase Study ON Transportation &logistics Dubai Ports WorldPavithraNo ratings yet

- Integrated Approach to Trade and Transport Facilitation: Measuring Readiness for Sustainable, Inclusive, and Resilient TradeFrom EverandIntegrated Approach to Trade and Transport Facilitation: Measuring Readiness for Sustainable, Inclusive, and Resilient TradeNo ratings yet

- DP WORLD Dubai Ports WorldDocument4 pagesDP WORLD Dubai Ports Worldthaophan.523202100574No ratings yet

- Facilitating Trade in Vaccines and Essential Medical Supplies: Guidance NoteFrom EverandFacilitating Trade in Vaccines and Essential Medical Supplies: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- 03-11-22 Transportation Market UpdateDocument16 pages03-11-22 Transportation Market UpdateSchneider100% (1)

- COVID-19 and Transport in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteFrom EverandCOVID-19 and Transport in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- Impact DHL Service DeliveryDocument12 pagesImpact DHL Service DeliveryvataxNo ratings yet

- W19238 PDF EngDocument14 pagesW19238 PDF Engvivek singhNo ratings yet

- Fostering Regional Cooperation and Integration for Recovery and Resilience: Guidance NoteFrom EverandFostering Regional Cooperation and Integration for Recovery and Resilience: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- J&T CompanyDocument16 pagesJ&T CompanyNORASHA SHAMIRA MOHAMMADNo ratings yet

- Accelerating Sustainable Development after COVID-19: The Role of SDG BondsFrom EverandAccelerating Sustainable Development after COVID-19: The Role of SDG BondsNo ratings yet

- Hazards On The Road AheadDocument15 pagesHazards On The Road AheadLukáš VávraNo ratings yet

- Asia-Pacific Trade Facilitation Report 2021: Supply Chains of Critical Goods amid the COVID-19: Pandemic—Disruptions, Recovery, and ResilienceFrom EverandAsia-Pacific Trade Facilitation Report 2021: Supply Chains of Critical Goods amid the COVID-19: Pandemic—Disruptions, Recovery, and ResilienceNo ratings yet

- The APEC 2012 PublicationDocument96 pagesThe APEC 2012 PublicationChris AtkinsNo ratings yet

- Asian Development Bank Trust Funds Report 2020: Includes Global and Special FundsFrom EverandAsian Development Bank Trust Funds Report 2020: Includes Global and Special FundsNo ratings yet

- A Study On Risk Measurement of Logistics in InternDocument13 pagesA Study On Risk Measurement of Logistics in InternAriful rimuNo ratings yet

- Asia’s Progress toward Greater Sustainable Finance Market Efficiency and IntegrityFrom EverandAsia’s Progress toward Greater Sustainable Finance Market Efficiency and IntegrityNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document4 pagesCase Study 1Mnhu VõNo ratings yet

- Doon Business School: Study of Exports of Chemical Products by SCMDocument43 pagesDoon Business School: Study of Exports of Chemical Products by SCMDullStar MOTONo ratings yet

- Chartering Services Development With The QFD Approach: Case Study On Liquid Freight Shipping CompaniesDocument9 pagesChartering Services Development With The QFD Approach: Case Study On Liquid Freight Shipping Companies黃詩烜No ratings yet

- Actividad 12 EvidenciaDocument10 pagesActividad 12 EvidenciaDaniela RomeroNo ratings yet

- 21321iied 0Document8 pages21321iied 0Ayman HossainNo ratings yet

- Critically Evaluate The Relationship Between The Organisational Effectiveness and Its International EnvironmentDocument12 pagesCritically Evaluate The Relationship Between The Organisational Effectiveness and Its International EnvironmentIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2020: Washington DC, May 2020Document109 pagesState and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2020: Washington DC, May 2020Rahmat SukmonoNo ratings yet

- 2022: From Supply Chain Chaos To Opportunity?: by Ti InsightDocument9 pages2022: From Supply Chain Chaos To Opportunity?: by Ti InsightGeneviraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Title Related To Marine TransportationDocument8 pagesThesis Title Related To Marine Transportationbser9zca100% (2)

- ASSIGNMENT 1 - Innovation and DisruptionDocument4 pagesASSIGNMENT 1 - Innovation and Disruptiontrang.vuNo ratings yet

- 1 Writing and Essay About Logistics CostsDocument7 pages1 Writing and Essay About Logistics CostsKaren Viviana Bermudez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument5 pagesCaseAlbenchel Milles Francisco VelardeNo ratings yet

- Information 12 00338 v2Document17 pagesInformation 12 00338 v2Human-Social DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- SFC-CDP - Closing The Logistics Emissions Gap July 2020 - CompressedDocument20 pagesSFC-CDP - Closing The Logistics Emissions Gap July 2020 - CompressedSudhir GotaNo ratings yet

- 3.28 VINCI Pilot Draft Case Study 21 October 2019Document20 pages3.28 VINCI Pilot Draft Case Study 21 October 2019verrerealNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Thesis Green LogisticsDocument7 pagesBachelor Thesis Green Logisticslaurawilliamslittlerock100% (2)

- Impact of COVID-19 On Transportation and Logistic On ChinaDocument20 pagesImpact of COVID-19 On Transportation and Logistic On ChinaTùng Nguyễn ThanhNo ratings yet

- Dubai Ports WorldDocument4 pagesDubai Ports WorldBlaizah Mae Salvatierra100% (1)

- GK 2ndDocument12 pagesGK 2ndvijay.sonpirdefNo ratings yet

- MANT334 Assingment 1Document5 pagesMANT334 Assingment 1James GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Background For International BusinessDocument19 pagesBackground For International BusinessSandia EspejoNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 1: Writing and Essay About Logistics CostsDocument5 pagesEvidencia 1: Writing and Essay About Logistics CostsjoseNo ratings yet

- Bam479 Case4 Basmafatteh 11-19-2020Document42 pagesBam479 Case4 Basmafatteh 11-19-2020api-532652635No ratings yet

- Logistics Management Jan 2021Document60 pagesLogistics Management Jan 2021Mehmet CiftciNo ratings yet

- About Richard Bolte SRDocument4 pagesAbout Richard Bolte SRLEGALBDPNo ratings yet

- (Preliminary Case Study) Share Mini Case Competition 2022Document20 pages(Preliminary Case Study) Share Mini Case Competition 2022Ace SquadNo ratings yet

- Fhwahep 19006Document54 pagesFhwahep 19006Thomas JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Handelsblatt - Path To Cop28Document14 pagesHandelsblatt - Path To Cop28Harsh VirNo ratings yet

- Caso 1 - Clase - Procter y Gamble - W28608-Pdf-Eng PDFDocument7 pagesCaso 1 - Clase - Procter y Gamble - W28608-Pdf-Eng PDFMaria Fernanda FloresNo ratings yet

- Acute Port Congestion and Emissions Exceedances As An Impact of COVID 19 Outcome: The Case of San Pedro Bay PortsDocument26 pagesAcute Port Congestion and Emissions Exceedances As An Impact of COVID 19 Outcome: The Case of San Pedro Bay PortsHbiba HabboubaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Critical Issues For The Future of Travel Tourism Report FINALDocument12 pagesUnderstanding The Critical Issues For The Future of Travel Tourism Report FINALIordache IoanaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Effect of The Pandemic To LogisticsDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Effect of The Pandemic To Logisticsarishya24No ratings yet

- 2 FS Bridging North America 2018 09 27 FINAL ENGLISHDocument2 pages2 FS Bridging North America 2018 09 27 FINAL ENGLISHRickyNo ratings yet

- Strama Paper FinalDocument31 pagesStrama Paper FinalLauren Refugio50% (4)

- Logistics Management Mart 2020Document68 pagesLogistics Management Mart 2020Mehmet CiftciNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Trucking IndustryDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Trucking Industrygzvp7c8x100% (1)

- Actividad 12 Evidencia 1Document11 pagesActividad 12 Evidencia 1Brayins officialNo ratings yet

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin - 4 December, 2012Document2 pagesEarth Negotiations Bulletin - 4 December, 2012adoptnegotiatorNo ratings yet

- Case #1Document5 pagesCase #1Mary Joyce GarciaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0967070X2200021X MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0967070X2200021X MainHbiba HabboubaNo ratings yet

- ODEM 2018 WhitepaperDocument70 pagesODEM 2018 WhitepaperryanNo ratings yet

- B 1250AJP JLG Service EnglishDocument794 pagesB 1250AJP JLG Service EnglishArturo Gomez RojasNo ratings yet

- T5 Fuse Etc InfoDocument32 pagesT5 Fuse Etc InfomafejoNo ratings yet

- Astm E2100 - 1 (En) PDFDocument5 pagesAstm E2100 - 1 (En) PDFRahul SamalaNo ratings yet

- Design Considerations Interlocking PavementsDocument18 pagesDesign Considerations Interlocking PavementsLionel TebonNo ratings yet

- The Official DSA Theory Test For Drivers of Large Vehicles OptDocument486 pagesThe Official DSA Theory Test For Drivers of Large Vehicles OptOnur Kafalı100% (2)

- Layout Optimization of Rail Expansion Joint On Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge For High-Speed RailwayDocument15 pagesLayout Optimization of Rail Expansion Joint On Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge For High-Speed RailwayParth TrivediNo ratings yet

- Excavadora 336NGHDocument16 pagesExcavadora 336NGHFinning CatNo ratings yet

- International Review of Law and Economics: Rosolino A. Candela, Vincent GelosoDocument13 pagesInternational Review of Law and Economics: Rosolino A. Candela, Vincent GelosoThiviyani SivaguruNo ratings yet

- Practice 2022Document47 pagesPractice 2022khoa bui dangNo ratings yet

- Key Features Key Specifications: Adr 80/03 ModelDocument4 pagesKey Features Key Specifications: Adr 80/03 ModelAndrew RegaNo ratings yet

- Crankshaft Main BearingsDocument5 pagesCrankshaft Main Bearingsma.powersourceNo ratings yet

- An Analysis Report of Implementation of Smart Parking System Using Internet of ThingsDocument4 pagesAn Analysis Report of Implementation of Smart Parking System Using Internet of ThingskhalidNo ratings yet

- Auto Abbreviation DictionaryDocument7 pagesAuto Abbreviation Dictionarytime2grow100% (1)

- Diagnosis From The Drivers SeatDocument101 pagesDiagnosis From The Drivers Seatabul hussain100% (1)

- The Conoco Weather ClauseDocument10 pagesThe Conoco Weather ClauseJayakumar SankaranNo ratings yet

- Boardingpass CONSTANTINDocument1 pageBoardingpass CONSTANTINMihaela Christina PleteaNo ratings yet

- STC - 2 Automatic Block Signal SystemsDocument43 pagesSTC - 2 Automatic Block Signal SystemsCarlos PanccaNo ratings yet

- 4.aircraft Nationality and Registration MarksDocument12 pages4.aircraft Nationality and Registration MarksNirmal FrancisNo ratings yet

- Home Lift - 01Document1 pageHome Lift - 01Nagarajan SNo ratings yet

- European Heavy-Duty Vehicle Market Development Quarterly: January - September 2023 (Final v2)Document11 pagesEuropean Heavy-Duty Vehicle Market Development Quarterly: January - September 2023 (Final v2)The International Council on Clean TransportationNo ratings yet

- RA712 Shipwreckers PDFDocument34 pagesRA712 Shipwreckers PDFJoe Conaway100% (1)

- Final Report - Ecc589 - Survey On Road Safety AwarenessDocument36 pagesFinal Report - Ecc589 - Survey On Road Safety AwarenessAmreen ShahNo ratings yet

- CE Module 12 - Highway and Transpo (Answer Key)Document6 pagesCE Module 12 - Highway and Transpo (Answer Key)Angelice Alliah De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Flight International 21 - 04 - 2020Document36 pagesFlight International 21 - 04 - 2020V DNo ratings yet

- K R - 35H-V R Ough T Errain Crane: (Power Jib)Document17 pagesK R - 35H-V R Ough T Errain Crane: (Power Jib)Testing GmailNo ratings yet

- Around The World in 80days Sum UpDocument3 pagesAround The World in 80days Sum UpLattanaphong MelavanhNo ratings yet

- Crow Esr5000Document238 pagesCrow Esr5000Eldelson Baggeto100% (1)

- QD0002-ADM-TEM-HSE-00027 HSE Issues Tracking Log Rev 0A 5.11.2020Document43 pagesQD0002-ADM-TEM-HSE-00027 HSE Issues Tracking Log Rev 0A 5.11.2020shah fahadNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities ThreatsDocument6 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities ThreatsNhi ĐặngNo ratings yet

- Report Header: Reprint From MFA-0000-000000Document5 pagesReport Header: Reprint From MFA-0000-000000gohoji4169No ratings yet