Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chap 3

Uploaded by

Quang HuyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chap 3

Uploaded by

Quang HuyCopyright:

Available Formats

3.

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit

management curriculum

Karabi C. Bezboruah

INTRODUCTION

What makes for an ethical nonprofit? To answer this, it is important to under-

stand the key aspect of nonprofit organizations – their focus on organizational

mission or their mission orientation. All programs provided by a nonprofit

organization are determined by its mission. According to Salamon and Anheier

(1992), nonprofits have five characteristics: (1) Nonprofits must be organ-

ized with established rules of operations, procedures, and bylaws that guide

the operations; (2) Nonprofits are privately incorporated and institutionally

separate and distinct from the government but work for public benefit; (3)

Nonprofit are self-governing entities and regulate their own operations; (4)

Any profits generated by a nonprofit must be reinvested into the organizational

mission; (5) Nonprofits are voluntary as volunteers are primarily engaged in

the leadership and operations. Support for such organizations by the public is

made in terms of voluntary donations of time and money. These characteristics

point to the fact that in the mission-driven work of nonprofits, the voluntary

board provides the governance function. However, there is no single own-

ership of nonprofits (Bhandari, 2010). While nonprofits are privately estab-

lished, they are answerable to the public. This is because they provide services

that benefit the public by institutionalizing operating procedures comparable to

the for-profit sector such as financial solvency.

Nonprofits tend to fill gaps in government services or act as policy imple-

menters for governmental agencies. Government grants, private donations, and

user charges are utilized to provide public benefit programs such as afterschool

education, child services, healthcare, and so forth. Thus, they are accountable

for their operations and finances. Additionally, the IRS regulations prohibit

nonprofits from engaging in activities that benefit private interests, which

provides the foundation for the public benefit as well as the ethical and legal

principles of operations. The governing board is responsible for stewarding

the organization and making it accountable. According to Carver (1997),

39

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

40 Teaching nonprofit management

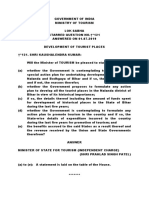

Table 3.1 Chapter objectives

Objectives NACC Guidelines

Examine concepts of ethics and 4.1 Values (trust, stewardship, service, voluntarism,

accountability by exploring code of ethics, civic engagement etc.) embodied in philanthropy

conflict of interests, and personal values and voluntary action

4.2 Foundations and theories of ethics as a discipline

and as applied in order to make ethical decisions

Understand the importance of ethics and 4.4 Trends associated with social responsibility,

accountability in nonprofit management sustainability and global citizenship within

cross-cultural and global contexts

4.5 Standards and codes of conduct that are appropriate

to paid and unpaid staff working in philanthropy and

the nonprofit sector

Examine cases to understand conflicts of 4.1 Values (trust, stewardship, service, voluntarism,

interest dilemmas civic engagement etc.) embodied in philanthropy

and voluntary action

4.4 Standards and codes of conduct that are appropriate

to paid and unpaid staff working in philanthropy and

the nonprofit sector

nonprofit boards hold the ultimate accountability for organizational action.

More specifically, nonprofits are accountable to the public, to their donors,

to the government, and therefore, have multiple stakeholders. The concept of

accountability (Williams and Taylor, 2013) includes upward accountability

(being held responsible by others), lateral accountability (taking responsibility

for staff and volunteers), and downward accountability (being responsible to

the needs of clients), which also includes public trust. Thus, nonprofits are

accountable to stakeholders within and outside of the organization, and their

conduct has implications for the reputation of other nonprofits.

This chapter discusses nonprofit ethics and accountability by aligning the

discussion to the NACC guidelines on teaching ethics shown in Table 3.1.

The chapter then defines the concepts of ethics and accountability, which is

followed by a discussion of the theories with practical teaching applications

for use in the classroom.

ETHICS

The term “ethics” is derived from the Greek word “ethicos”, meaning habit

or customs relating to morals. Ethics is defined as “well-based standards of

right and wrong that prescribe what humans ought to do, usually in terms

of duties, principles, specific virtues, or benefits to society” (Johnson, 2005,

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 41

p. 10). Nonprofits are perceived to be trustworthy and ethical as they are not

motivated by profits, and therefore would not be involved in any unethical

behavior. However, the 2007 National Nonprofit Ethics Survey found that

unlawful conduct and unethical behavior was increasing in the nonprofit

sector, with financial fraud much higher in this sector compared to the

for-profit and government sectors. It found that when the governing board

establishes and follows through on ethical policies, organizations exhibit

strong ethical standards. Several forms of ethical challenges can affect a non-

profit organization. Some common internal and external challenges to ethical

conduct are: accountability, conflict of interest, financial disclosures, surplus

accumulation, remuneration outside of the organization, salary and benefits,

personal relationships, contract processes, and fundraising, political campaign

activities, reporting, and stewardship (Grobman, 2011; Zack, 2003).

People have a sense of right and wrong, and these individual beliefs about

appropriate behavior are developed over a person’s lifetime. These beliefs

also help shape one’s professional behavior and interactions. Tschirhart and

Bielefeld (2012) argue that integrating a professional code of conduct and

ethics into organizational operations can help avoid conflicts. Ethical conduct

can also be developed and fostered by value-based leadership (Jeavons, 2005)

and application of incentives for proper conduct that signals organization-wide

accountability. Furthermore, nonprofits also are accountable to the expec-

tations of society. Public charities that are supported through donations are

held to higher standards and are regulated and accredited by agencies (Charity

Navigator, Better Business Bureau (BBB), Wise Giving Alliance, etc.) besides

the IRS (Grobman, 2015).

ACCOUNTABILITY

Accountability is being answerable to the diverse stakeholders of a nonprofit

(Young, 2002). It is maintained through proper reporting and publishing of

the organization’s activities and impact via annual reports, tax returns, news-

letters and so forth. It also involves being audited and evaluated by external

agencies for ethical financial conduct and program effectiveness. Calls for

accountability in nonprofits increased after some of the major organizations

were tainted by fraud and financial mismanagement scandals in the early

1990s (Kim, 2005). Accountability means answerability to the stakeholders for

the work conducted by the nonprofit. Organizations have established multiple

and complex monitoring mechanisms such as financial and program audits,

licensures, annual contract evaluations, and outcome-based assessments for

financial and program-related accountability. For example, United Way

requires strict and comprehensive measures of financial reporting, governance,

ethics, diversity, and operations for each of its chapters to ensure accountabil-

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

42 Teaching nonprofit management

ity. Additionally, codes of ethics have been put in place by governing boards

to ensure lawful behavior by employees and volunteers in regular operations

(Dicke, 2002; Dicke and Ott, 1999; Salamon, 1999).

RELEVANT THEORIES

There are many theories used to explain nonprofit ethics and accountability.

The theories discussed in this chapter are outlined below.

Principal–Agent Theory

One popular theory is the Agency theory, also known as the Principal–Agent

theory. The Executive Director acts as the agent in leading the organization for

the Board of Directors, who are the principal. According to Perrow (1986), the

Principal–Agent theory assumes organizational interactions as a series of con-

tracts. He states that the principal is the buyer of goods or services, and the pro-

vider of the goods or services is the agent. “The principal–agent relationship

is governed by a contract specifying what the agent should do and what the

principal must do in return” (1986, p. 224). Since the agent is knowledgeable

and well-equipped to provide the services, there exists information asymmetry,

with the agent being in an advantageous position. Because of this goal conflict,

the principal will attempt to regulate the behavior of the agent to conform to

the norms as well as wishes of the principal. This theory, therefore, focuses on

accountability as it explains the relations between the internal organizational

actors, and the organization and external stakeholders (Coule, 2015). While in

nonprofit organizations, there is a lack of clarity regarding ownership and who

should be considered “principal” (Miller, 2002; Brody, 1996), the board serves

as a regulatory body by ensuring compliance and conformance to safeguard

founders’ interests by overseeing management operations (Cornforth, 2004).

The absence of a clearly defined “principal” in nonprofits can lead to misuse

of power and assumption of excessive risks resulting in unethical behavior

(Bhandari, 2010). Scholars have applied this theory in a variety of settings to

explain contractual relations between organizations, boards and directors, and

managers and employees (Van Slyke, 2007), executive compensation (Garen,

1994), and many other areas. Because of the presence of multiple stakeholders

with conflicting goals and interests, the agency problem is more complex in

nonprofit organizations.

Stewardship Theory

This theory “defines situations in which managers are not motivated by

individual goals, but rather are stewards whose motives are aligned with the

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 43

objectives of their principals” (Davis et al., 1997, p. 21). This theory also

assumes individual goal conflict between the principal and the steward, but

they are motivated by shared collective interests. Trust, reciprocity, goal

alignment, job satisfaction, stability, and reputation are some of the motivating

factors and governance mechanisms of the steward. There are high initial costs

of time and monetary investment to involve nonprofit boards as stewards of

the organization. This cost becomes necessary in a principal–stewardship rela-

tionship as information sharing and collective goal accomplishment enhance

organizational transparency and accountability. Bundt (2000) suggests that

this theory is better applicable to nonprofit management as it focuses on shared

information and collective goals, with the board partnering and supporting the

executive director. The stewardship theory is relevant to nonprofit ethics and

accountability because in instances of goal conflict arising from self-interests,

unethical behavior of a principal can impact the future of the organization.

Stakeholder Theory

This theory suggests that organizations have multiple stakeholders with varied

interests, and therefore their representation on the board is important to exer-

cise oversight and control over management. Stakeholders are “any person or

group that is able to make a claim on an organization’s attention, resources

or output or who may be affected by the organization” (Lewis, 2001, p. 202).

Stakeholders may be internal or external to the organization. For example,

managers and employees are internal stakeholders, and customers, competi-

tors, and suppliers are external stakeholders. There are also stakeholders that

interface with the organization. In nonprofits, the board of directors are the

interface stakeholders, as they represent the organization to the outside world

and facilitate the accomplishment of organizational mission (Savage et al.,

1991). The stakeholder theory is relevant to ethics and accountability because

the stakeholders should be acting in an ethical manner and be accountable to

the general public; however, conflicts of interest arise when stakeholders make

decisions based on self-interest.

In summary, the aforementioned theories have been applied to examine and

explain ethical and accountability issues in nonprofit management. Principal–

agent theories touted accountability as “the means by which individuals and

organizations report to a recognized authority and are held responsible for

their actions” (Edwards and Hulme, 1996, p. 967). The stakeholder approach

considers the existence of multiple individuals and groups that are within and

outside of the organizations with divergent interests and priorities, requiring

“continuous social, political . . . and moral processes” (Watson, 2006, p. 52).

Together, these theories explain ethical conduct and accountability in the

management of organizations. Coule (2015) suggests that accountability

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

44 Teaching nonprofit management

in the agency theories is based on explicit and objective standards or rules,

and is enforced through monitoring and auditing. In the stakeholder-based

approach, accountability is based on objective rules and subjective standards,

and enforced through negotiation, monitoring and auditing. Combining these

theories can provide a more comprehensive assessment of nonprofit ethics and

accountability.

ETHICAL CHALLENGES AND GOVERNANCE OF

NONPROFITS

Ethical challenges are common and can arise at all levels in for-profit, nonprofit,

and government sectors. Some ethical issues within nonprofits can result in

criminal violations or civil liability; for example, fraud, misrepresentation, and

misappropriation of assets (Grobman, 2015). However, the common ethical

problems involve gray areas or activities that are on the fringes of fraud, or that

involve conflicts of interest, misallocation of resources, or inadequate account-

ability and transparency (Grobman, 2015; Rhode and Packel, 2009). Trust is

the hallmark of nonprofit organizations, and in a 2015 survey, a majority of the

respondents (80 percent) said charities do a “very good” or “somewhat good

job” of helping people. However, many were concerned about the finances:

33 percent said charities do a “not too good” or “not at all good” job spending

money wisely, and 41 percent said their leaders are paid too much. “Unwise”

spending of money included expenses on salaries or other administrative costs

and advertising (Perry, 2015). These surveys highlight the public perception

of and attitude towards the nonprofit sector that includes a wide variety of

diverse organizations ranging from small human service charities to large

charitable hospitals. Grouping these organizations within one sector confounds

the diversity in size, structure, funding streams, and missions. Most of these

perceptions are drawn from media highlighting cases of unethical conduct

and financial mismanagement by charities. Organizations such as the Nature

Conservancy, the Red Cross, the United Way, Educorp, and local foundations

in several communities were in the news for financial mismanagement. Such

ethical lapses, whether perceived or real, result in public distrust for the entire

sector, leading to increased calls for accountability and scrutiny of operations.

Accountability in nonprofits comes in many forms and can generally be

in the realm of fiscal, ethical, and performance accountability (Schatteman,

2013). Most nonprofits have set standards and guidelines for regular oper-

ations for maintaining procedural accountability. Additionally, nonprofits

must adhere to legal and regulatory standards as well, such as being registered

with state and federal agencies for tax exempt status, disclosure of financial

information annually through the IRS Form 990, and maintaining standards

for external watchdog groups (Schatteman, 2013). Some measures that are

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 45

called for to enhance accountability by nonprofits are: being transparent with

the activities and finances by voluntarily disclosing such information; having

organizational ethics policies; periodic review and accreditation by external

agencies; and program evaluation for nonprofit effectiveness and impact.

Nonprofit employees are held to a higher standard as they work to accom-

plish a public benefit mission, are motivated by mission more than money,

and are often regarded as equivalent to public sector employees (Rotolo and

Wilson, 2006). There can be a variety of ethical challenges in nonprofits

such as mission compliance, accountability to funders, fundraising, internal

human resource issues, ethical reporting, managing conflicting stakeholder

requirements, effective communication and so forth. An emerging challenge is

the use of personal social media and its impact on the organization, resulting

in a call for organizational social media policies for enhancing accountability

(Bezboruah and Dryburgh, 2012). Furthermore, employees or volunteers can

enhance trust by reporting any unethical conduct, financial mismanagement, or

unprofessional behavior without any fear of retaliation through whistleblower

protection policies.

Ethical Dilemmas

There are many gray areas of ethical dilemmas affecting nonprofit manage-

ment. Examples include funding education in low-income neighborhoods

with money earned from selling drugs, or buying office furniture from a board

member’s company, or paying rent for the use of the facilities owned by

a board member. While not all are financial misappropriation, they signal

impropriety and dishonesty, which affect the trustworthiness of a nonprofit.

As stated earlier, nonprofits are held to higher standards and considered

trustworthy because they are motivated by mission and not by profits. One

remedy is to have ethical policies and standards for the organization that are

effectively communicated to all its volunteers and employee (see Table 3.2).

Regular training and annual workshops on compliance and ethical issues can

help enhance accountability. Furthermore, as stewards of nonprofit organi-

zations, the board of directors can ensure adherence to ethical conduct and

accountability by following principles of good governance and ethical practice

listed in Table 3.2.

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

46 Teaching nonprofit management

Table 3.2 Principles for good governance and ethical practice

Effective Governance Strong Financial Oversight

1. Board Responsibilities 21. Financial Records

2. Board Meetings 22. Annual Budget, Financial Performance and

Investments

3. Board Size and Structure 23. Loans to Directors, Officers, or Trustees

4. Board Diversity 24. Resource Allocation for Programs and

Administration

5. Board Independence 25. Travel and Other Expense Policies

6. CEO Evaluation & Compensation 26. Expense reimbursement for Non-business

Travel Companions

7. Separation of CEO, Board Chair, and Board

Treasurer Roles

8. Board Education & Communication

9. Evaluation of Board Performance

10. Board Member Term Limits

11. Review of Governing Documents

12. Review of Mission and Goals

13. Board Compensation

Legal Compliance & Public Disclosure Responsible Fundraising

14. Laws & Regulations 27. Accuracy and Truthfulness of Fundraising

Materials

15. Code of Ethics 28. Compliance with Donor’s Intent

16. Conflicts of Interest 29. Acknowledgment of Tax-Deductible

Contributions

17. “Whistleblower” policy 30. Gift Acceptance policies

18. Document & Data Retention and 31. Oversight of Fundraisers

Destruction

19. Protection of Assets 32. Fundraiser Compensation

20. Availability of Information to the Public 33. Donor Privacy

Source: Independent Sector (2018).

What Can be Done?

Scholars and practitioners suggest that upholding ethical conduct and account-

ability is an ongoing process. Regular review of organizational operations,

processes, and procedures can assist in the identification and mitigation of

issues that can hamper the reputation of the organization. Table 3.3 lists some

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 47

Table 3.3 Accountability checklist

1. Develop a culture of accountability and transparency.

2. Adopt a Statement of Values and Code of Ethics.

3. Adopt a Conflict of Interest Policy.

4. Ensure that the board of directors understands and can fulfill its financial responsibilities.

5. Conduct independent financial reviews, particularly audits.

6. Ensure the accuracy of and make public your organization’s Form 990.

7. Be transparent.

8. Establish and support a policy on reporting suspected misconduct or malfeasance, also known as

Whistleblower Protection Policy.

9. Remain current with the law

Source: Independent Sector (2018).

recommendations adapted from the Independent Sector that can ensure com-

mitment to the organizational mission and uphold public trust.

Let’s consider the following ethical dilemmas in nonprofit management for

classroom discussions:

1. Should the Executive Director get bonuses and raises for fundraising

success?

2. If money was donated for a specific program that already has excess

funding, should a nonprofit divert the money to another under-funded

program?

3. Should a nonprofit share its donor information with other organizations or

employees?

4. Is it alright for nonprofit employees to use personal social media to speak

in favor or against political candidates?

5. Is it alright to not mention earnings from mission unrelated business

income in the tax returns?

Students can work on these in small groups and then discuss the general

implications.

CLASSROOM ACTIVITY

The objective of this exercise is to assess the transparency levels of nonprofits.

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

48 Teaching nonprofit management

Instructor: Group students into small groups of 3–5, and ask them the

following:

1. Access any nonprofit’s website and make a list of the information provided

for the public: tax returns; annual reports; policies for ethics, whistleblower

protection, conflicts of interest, and so forth. Each group will review a dif-

ferent nonprofit.

2. List stakeholders for your selected organization (including internal and

external stakeholders).

3. Access this nonprofit in BBB Wise Giving Alliance or Charity Navigator

and check its credentials/review.

4. What do you conclude from this exercise? Does having information make

an organization transparent and accountable? Why or why not? Compare

your notes with the other groups.

5. Based on this activity, what would you recommend to other nonprofits?

CASE STUDIES

1. Conserve and Benefit

Sunshine Org is a nonprofit focused on teaching children about nature and

environment conservation. The organization pursues its mission through

a park at the edge of a city in an urban area. It hosts school field trips, rents

out the facilities for weddings, office meetings, and other social events, and

charges fees for using the park for a variety of uses. The park includes a lake

that is used for boating, canoeing, and other water sports. This park is located

near a blighted and high crime neighborhood, and was undeveloped for many

years. The founder of Sunshine Org, Linda Brown, bought this land at a very

low price, and left it untouched with weeds growing all over the land. When the

city initiated development initiatives about five years ago, this neighborhood

began attracting more families, and housing quality improved. Linda then

cleaned up the land and let wildflowers grow, and maintained it regularly. It

led to new flora and fauna. With the waterfront view, the land value increased,

resulting in several offers from real estate developers for the land.

In order to maintain ownership, Linda established the land as a nonprofit

park in 2015, with the mission of environmental conservation. She serves as

the chair of the board of directors and is also actively involved in the man-

agement of the nonprofit. The other directors include family members and

close friends. The nonprofit provides educational tours, meetings, weddings,

concerts, and other events. The nonprofit’s office is located within the park as

well. For the services and activities offered, the nonprofit charges fees from its

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 49

patrons. The money generated from the fees is used to pay for the maintenance

and upkeep of the park, administrative costs, and for rent of the office facili-

ties. Being a nonprofit, the park is exempt from federal taxes, and with income

less than $50,000 per annum, it never completed the IRS annual reporting

return also known as Form 990.

Instructor preparation: This case may be read out loud in class prior to dis-

cussing the chapter concepts. Then, assign the students to small groups and ask

the following:

1. What do you understand by the following terms: ethics, accountability,

values, and conflict of interest? What is the difference between ethics and

morality?

2. Did you find any ethical issues in this case? If no, do you think this is

typical of all nonprofits that you are aware of? If yes, list them.

3. Are you aware of any code of ethics at your workplace? If yes, please share

how this is communicated with the employees/ staff.

Time (including group work): About 20 minutes.

Debrief: Go over the concepts and theories of ethics and accountability and

connect them to the questions listed above.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Did you find any ethical issues in this case? How would you categorize

the issues present in the case? [Note: Instructors can use these prompt

words: ethical, moral, conflict of interest etc., only if the students are

struggling to categorize. It is better to let the students discuss in groups

and respond.]

2. List (if any) conflict of interest issues are present.

3. Draft a code of ethics for this organization, and recommend ways to

communicate as well as train employees on ethical conduct.

4. What measures would you recommend for addressing conflict of inter-

est dilemmas?

5. What measures would you recommend for addressing accountability of

the organization?

Time: 30 minutes.

Debrief: Acknowledge how there will be diversity in beliefs regarding what is

ethical and what is not. Connect the discussion to the stakeholders involved,

and how personal ethical values would shape the identification of professional

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

50 Teaching nonprofit management

ethics and conflict of interest issues. Let students connect this case to their own

experiences with professional ethical dilemmas and conflict of interests.

2. Shock Therapy

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) is a nonprofit organiza-

tion that began in 1980 and became first a national, then an international, voice

for animal rights. Over its history, PETA has taken on a number of issues such

as the cruel treatment of animals in factory farms, in research labs, and in cir-

cuses. Its activities have included undercover reporting, protests, advertising

campaigns, and litigation. PETA has scored a number of successes. Undercover

investigation by PETA of a laboratory in Silver Springs, Maryland, led to the

first US police raid on an animal treatment facility. A protest campaign against

McDonald’s in 2000 led to its becoming the first major US corporation to

impose, on all their suppliers, minimum standards in the treatment of chickens.

While the ultimate goal of the organization is the liberation of all animals

from suffering caused by humans, PETA does not itself engage in the more

extreme forms of activism that characterize other groups, such as the Animal

Liberation Front (ALF). Instead, PETA aims at improving the living condi-

tions for animals and reducing the demand for animal products. This approach

has sometimes led to the criticism from more radical animal rights groups that

PETA is not so much about animal rights as about animal welfare.

The founder and guiding force behind PETA, Ingrid Newkirk, has long used

aggressive, attention-grabbing campaigns to bring the organization’s message

to the public. It would seem that nothing is too tasteless or offensive for PETA,

as long as people talk. Some of its noteworthy campaigns have involved

linking the treatment of animals with the Holocaust, with slavery, and with

certain infamous serial killers. PETA volunteers have disrupted fashion shows,

dragged themselves through the streets in leg-hold traps, and have dumped

money soaked in fake blood on audiences at fur fairs. Their tactics became

so notorious that in 1997 The Onion ran a satirical article, “Heroic PETA

Commandos Kill 49, Save Rabbit.”

Another technique PETA has used to attract attention is sex. To protest

against the running of the bulls in Pamplona, Spain, it sponsored a “Running

of the Nudes” two days before. To protest against the wearing of fur, they

featured attractive models (both male and female) in the campaign, “I’d Rather

Go Nude Than Wear Fur.” To promote vegan diets, they sent out “Lettuce

Ladies,” dressed in bikinis made of strategically placed lettuce leaves. PETA

have announced plans to host a soft porn website, www.peta.xxx.

Some of these tactics have drawn criticism from various women’s groups

for objectifying women. In an interview by Michael Specter, published in the

New Yorker on 14 April 2003, Newkirk commented on Pamela Anderson’s

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 51

appearance as a Lettuce Lady: “Who could ask for anyone better than Pam?

People drool when they look at her. Why wouldn’t we use that? We need all

the drooling we can get.” (Source: Connolly et al., 2013.)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Do you think there is anything unethical about the tactics used by

PETA in accomplishing their mission? Why or why not? List your

justifications.

a. Instructors: Assign the students to 2 groups (“approve” and “dis-

approve” of tactics) and ask them to debate by applying sound

reasoning and using concepts of ethics.

2. How would you rate the success of such campaigns to further

a mission? Why?

3. Are the activities (tactics used) involved aligned to the mission of the

organization?

4. Identify stakeholders of this organization. List all the parties to whom

PETA is accountable.

5. Research other campaigns of nonprofit organizations that used similar

or out of the box tactics to further their mission? How impactful are

they? What lessons can be drawn from them?

Time for Debate: 20 minutes; Time for the whole exercise: 45 minutes.

3. Donor Strategy

Affordable Housing for All is a regional nonprofit that works to provide

low-income families with housing options. It is one year into its new expan-

sion strategy – expand its services to a neighboring town to the West – selected

based on both need and feasibility.

A donor approached the Executive Director, Lisa, with the intention of sup-

porting the nonprofit’s expansion at a very significant level. But the support

comes with a demand; they must also expand their services to a town nearby,

but outside of the expansion plan. Lisa is conflicted. On one hand, the funds

would be more than enough to cover the additional cost and would also help

support the nonprofit’s current expansion plan. Also, the nonprofit would be

providing a beneficial service to the additional community, even if it wasn’t

the nonprofit’s original plan. Yet, Lisa is concerned that allowing donors to set

the strategic priorities of the nonprofit is dangerous and sets a bad precedent.

She is also concerned that taking on the additional area could compromise their

effectiveness in the other communities. (Source: Skeet and Harrington, 2016.)

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

52 Teaching nonprofit management

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Should Lisa take the donation? What steps should she take to make

a decision?

2. Restricted gifts are common, but generally go to existing programs or

ones proposed by the nonprofit. Is creating a new program crossing the

line?

3. If Lisa takes the donation, should she disclose to the board, staff, or the

community the nature of the arrangement?

4. What would you recommend in this situation? What steps would you

take to make a decision?

Time: 15 minutes.

CONCLUSION

Nonprofit organizations are mission driven. The board of directors is made

up of volunteers that govern and lead the organization to accomplish its

mission. Most of the programs are implemented by its employees and vol-

unteers. While employees and staff of nonprofits are motivated by a sense of

mission, we do find instances of financial mismanagement, fundraising fraud,

conflict of interest issues, inadequate or misrepresentation of reporting, and

other ethical issues. Such activities can negatively impact the public trust and

support enjoyed by nonprofits, resulting in program closure. Some of these

improprieties are obvious and deliberate while others fall in gray areas. The

principal–agent, stewardship, and stakeholder theories can assist in explaining

the expectations of the diverse internal and external stakeholders, and how

responsible nonprofit leadership can address these multiple demands. Instilling

a culture of ethical behavior from the leadership to the frontline workers can

enhance employee satisfaction, uphold public trust, and enhance support for

programs.

In conclusion, taking Tschirhart and Bielefeld’s (2012, p. 24) suggestion,

a simple mechanism to maintain ethical behavior is to ask the following ques-

tions before acting on a proposed action:

1. Is it legal? (Am I violating any laws or organizational policies?)

2. Is it balanced and fair to all concerned? (Will my action create a win–win

situation?)

3. How will it make me feel about myself? (Will I be proud of what I have

done and willing to tell others what I did?)

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 53

Table 3.4 Ethics resources

Code of Ethics

Charles Stewart Mott Foundation https://www.mott.org/about/values/

Fundraising Ethics https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools

-resources/ethical-fundraising

Leadership Ethics https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools

-resources/ethical-leadership-nonprofits

Financial Transparency https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools

-resources/financial-transparency

Sample Whistleblower Protection Policy https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools

-resources/whistleblower-protections-nonprofits

Independent Sector Checklist for Accountability https://independentsector.org/wp-content/uploads/

2018/01/Accountability-Checklist-v2-1-2-18.pdf

Business Ethics http://www.spibr.org/Ethical_Mgmt_by_Blanchard

_and_Peal.pdf

Code of Ethics for Board Members http://www.mtnonprofit.org/uploadedFiles/Files/

Org-Dev/Principles_and_Practices/Other_Sample

_Docs/NCN-Code-of-Ethics.pdf

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. What do you understand by nonprofit ethics? List at least five things

that nonprofit managers need to be cognizant of while upholding

ethical conduct.

2. Who are the stakeholders of a nonprofit organization? Do they have

similar expectations from the nonprofit? Why or why not? How would

a nonprofit maintain accountability to these stakeholders?

3. How do the theories (Principal–Agent, Stewardship, and Stakeholder)

explain nonprofit accountability? What is your opinion about a com-

bined theory to explain ethics and accountability? What recommenda-

tion would you make?

4. What information should a nonprofit post on their websites to inform

the public about its work? How would the public assess a nonprofit’s

practices and effectiveness from this information?

5. How would you make connections between a nonprofit employee’s

personal, professional, organizational, and social ethics? Make a list

of the attributes you would include for each. Discuss why you selected

these attributes.

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

54 Teaching nonprofit management

REFERENCES

Bezboruah, K. and Dryburgh, M. (2012). Personal Social Media Usage and its

Impact on Administrative Accountability: An Exploration of Theory and Practice.

International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 15(4), 469–95.

Bhandari, S. (2010). Ethical Dilemma of Nonprofits in the Agency Theory Framework.

Journal of Leadership, Accountability & Ethics, 8(2), 33–40.

Brody, E. (1996). Agents Without Principals: The Economic Convergence of the

Nonprofit and For-Profit Organizational Forms. New York Law School Law Review,

40(3), 457–536.

Bundt, J. (2000). Strategic Stewards: Managing Accountability, Building Trust.

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(4), 757–77.

Carver, J. (1997). Boards that Make a Difference (2nd edn). San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Connolly, P., Althaus, R., Brinkman, A., Ross, J. and Skipper, R. (2013). Cases for

the Seventeenth Intercollegiate Ethics Bowl. Annual Meeting of the Association for

Practical and Professional Ethics, San Antonio, Texas.

Cornforth, C. (2004). The Governance of Cooperatives and Mutual Associations:

A Paradox Perspective. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 75, 11–32.

Coule, T. (2015). Nonprofit Governance and Accountability: Broadening the Theoretical

Perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(1), 75–97.

Davis, J., Schoorman, F. and Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a Stewardship Theory of

Management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47.

Dicke, L. (2002). Ensuring Accountability in Human Services Contracting: Can

Stewardship Theory Fill the Bill? American Review of Public Administration, 32(4),

455–70.

Dicke, L. and Ott, J. (1999). Public Agency Accountability in Human Service

Contracting. Public Productivity & Management Review, 22(4), 502–16.

Edwards, M. and Hulme, D. (eds) (1996). Beyond the Magic Bullet: NGO Performance

and Accountability in the Post-Cold War World. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian

Press.

Garen, J. (1994). Executive Compensation and Principal–Agent Theory. Journal of

Political Economy, 102(6), 1175–99.

Grobman, G. (2011). The Nonprofit Handbook: Everything You Need to Know to Start

and Run Your Nonprofit Organization. Harrisburg, PA: White Hat Communications.

Grobman, G. (2015). Ethics in Nonprofit Organizations: Theory and Practice (2nd

edn). Harrisburg, PA: White Hat Communications.

Independent Sector (2018). What are the Principles? Principles for Good Governance

and Ethical Practice. Accessed 20 May 2018 at https:// independentsector

.org/

programs/principles-for-good-governance-and-ethical-practice/.

Jeavons, T. (2005). Ethical Nonprofit Management. In Herman, R. and associates (eds),

The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership & Management (2nd edn). San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 178–205.

Johnson, C. (2005). Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Kim, S. (2005). Balancing Competing Accountability Requirements: Challenges in

Performance Improvement of the Nonprofit Human Services. Public Performance

& Management Review, 29(2), 145–63.

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Ethics and accountability in nonprofit management curriculum 55

Lewis, D. (2001). The Management of Non-Governmental Development Organizations:

An Introduction. London: Routledge.

Miller, J. (2002). The Board as a Monitor of Organizational Activity: The Applicability

of Agency Theory to Nonprofit Boards. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 12,

429–50.

Perrow, C. (1986). Complex Organizations: A Critical Essay. New York: Random

House.

Perry, S. (2015). 1 in 3 Americans Lacks Faith in Charities, Chronicle Poll Finds.

Chronicle of Philanthropy. Accessed 20 May 2018 at https://www.philanthropy

.com/article/1-in-3-Americans-Lacks-Faith/233613.

Rhode, D. and Packel, A. (2009). Ethics and Nonprofits. Stanford Social Innovation

Review, 7(3), 29–35.

Rotolo, T. and Wilson, J. (2006). Employment sector and volunteering: The

Contribution of Nonprofit and Public Sector Workers to the Volunteer Labor Force.

The Sociological Quarterly, 47(1), 21–40.

Salamon, L. (1999). America’s Nonprofit Sector: A Primer (2nd edn). New York:

Foundation Center.

Salamon, L. and Anheier, H. (1992). In Search of the Nonprofit Sector. I: The Question

of Definitions. Voluntas, 3(2), 125–51.

Savage, G., Nix, T., Whitehead, C. and Blair, J. (1991). Strategies for Assessing and

Managing Organizational Stakeholders. Academy of Management Executive, 5(2),

61–75.

Schatteman, A. (2013). Nonprofit Accountability: To Whom and For What?

International Review of Public Administration, 18(3), 1–6.

Skeet, A. and Harrington, J. (2016). How Much Say Should Donors Get on Strategy?

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, Santa Clara University.

Tschirhart, M. and Bielefeld, W. (2012). Managing Nonprofit Organizations. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Van Slyke, D. (2007). Agents or Stewards: Using Theory to Understand the

Government–Nonprofit Social Service Contracting Relationship, Journal of Public

Administration Research and Theory, 17(2), 157–87.

Watson, T. (2006). Organising and Managing Work (2nd edn). Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Williams, A. and Taylor, J. (2013). Resolving Accountability Ambiguity in Nonprofit

Organizations. Voluntas, 24(3), 559–80.

Young, D. (2002). The Influence of Business on Nonprofit Organizations and the

Complexity of Nonprofit Accountability: Looking Inside as well as Outside. The

American Review of Public Administration, 32(1), 3–19.

Zack, G. (2003). Fraud and Abuse in Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Prevention

and Detection. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Karabi C. Bezboruah - 9781788118675

Downloaded from https://www.elgaronline.com/ at 04/10/2024 03:25:57PM

via Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

You might also like

- 6 Ethical Communities WorksheetDocument3 pages6 Ethical Communities Worksheetapi-686122256No ratings yet

- Ethics Reflection Wk1Document4 pagesEthics Reflection Wk1Lori MartinNo ratings yet

- Becoming a Reflective Practitioner: The Reflective Ethical Facilitator's GuideFrom EverandBecoming a Reflective Practitioner: The Reflective Ethical Facilitator's GuideNo ratings yet

- IOP4862 Theme 1 Lesson 4Document8 pagesIOP4862 Theme 1 Lesson 4Swazi ShabalalaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Reflection PaperDocument6 pagesEthics Reflection PaperAshley FritzNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Business EthicsDocument22 pagesLesson 3 Business Ethicsweird childNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 (The Ethical and Social Environment)Document17 pagesChapter 4 (The Ethical and Social Environment)babon.eshaNo ratings yet

- Infusing Values and Ethics in An Organization-Full PaperDocument9 pagesInfusing Values and Ethics in An Organization-Full PapermihirddakwalaNo ratings yet

- Quiz of ManagementDocument6 pagesQuiz of Managementnaveed abbasNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics: Navigating Moral Dilemmas in the Corporate WorldFrom EverandBusiness Ethics: Navigating Moral Dilemmas in the Corporate WorldNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics in Public Relations 01Document14 pagesCode of Ethics in Public Relations 01dfddtrdgffd100% (1)

- Ethics Reflection PaperDocument7 pagesEthics Reflection PaperDavid Bacon100% (1)

- Abstract:: Keywords: Ethics, Organizational Ethics, Ethical Practices, TransparencyDocument7 pagesAbstract:: Keywords: Ethics, Organizational Ethics, Ethical Practices, TransparencyyahyeNo ratings yet

- Rationale Part 1Document7 pagesRationale Part 1api-511153690No ratings yet

- Discussing The Importance of Organizational Culture in Strategic Management (25) Solution by Anthany Tapiwa MazikanaDocument30 pagesDiscussing The Importance of Organizational Culture in Strategic Management (25) Solution by Anthany Tapiwa MazikanaGift SimauNo ratings yet

- Discussing The Importance of Organizational Culture in Strategic Management (25) Solution by Anthany Tapiwa MazikanaDocument30 pagesDiscussing The Importance of Organizational Culture in Strategic Management (25) Solution by Anthany Tapiwa MazikanaGift SimauNo ratings yet

- DPS 504 AssignmentsDocument17 pagesDPS 504 AssignmentsAbdi AbdullahiNo ratings yet

- Cultural EthicsDocument56 pagesCultural EthicsGanesan MurthyNo ratings yet

- CSC Presentation On Ethical LeadershipDocument44 pagesCSC Presentation On Ethical Leadershipjose adrianoNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Public Administration: C6: Public Systems ManagementDocument51 pagesEthics and Public Administration: C6: Public Systems ManagementpeeyushNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Organization - TataDocument13 pagesEthics in Organization - TataVineet Patil50% (2)

- How Ethical Organizational Culture Impacts Organizational ClimateDocument19 pagesHow Ethical Organizational Culture Impacts Organizational ClimatereillyfrNo ratings yet

- Section 1-4 Ethics and Accountability in The Nigerian Civil ServiceDocument12 pagesSection 1-4 Ethics and Accountability in The Nigerian Civil Servicetosinbamidele2No ratings yet

- 14.social Responsibility and Managerial EthicsDocument4 pages14.social Responsibility and Managerial EthicsSonia RajNo ratings yet

- Handbook for Strategic HR - Section 2: Consulting and Partnership SkillsFrom EverandHandbook for Strategic HR - Section 2: Consulting and Partnership SkillsNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Unethical Leadership Issues Cases and Dilemmas With Case Studies PDFDocument8 pagesEthical and Unethical Leadership Issues Cases and Dilemmas With Case Studies PDFRiva Choerul FatihinNo ratings yet

- Codes of Ethics and Business ConductDocument14 pagesCodes of Ethics and Business ConductMaricel EranNo ratings yet

- Professional EthicsDocument16 pagesProfessional EthicsakashdeepNo ratings yet

- Ethics - WorkDocument5 pagesEthics - WorkNyakashaiaja kennethNo ratings yet

- Role of Ethics in Organizational BehaviourDocument16 pagesRole of Ethics in Organizational BehaviourJ LAL0% (1)

- Title: Management Conflict and EthicsDocument39 pagesTitle: Management Conflict and EthicspiklengNo ratings yet

- ETHICSANDLEADERSHIPDocument8 pagesETHICSANDLEADERSHIPP Olarte ESNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 EthicsDocument20 pagesTopic 1 EthicsdrbrijmohanNo ratings yet

- Ethics Unleashed Navigating The Moral Landscape of Non Profit BusinessDocument27 pagesEthics Unleashed Navigating The Moral Landscape of Non Profit Businessservicesbyliz.peoriaNo ratings yet

- The Glass Ceiling in Chinese and Indian Boardrooms: Women Directors in Listed Firms in China and IndiaFrom EverandThe Glass Ceiling in Chinese and Indian Boardrooms: Women Directors in Listed Firms in China and IndiaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Corporate Culture Ethics and LeadershipDocument28 pagesCorporate Culture Ethics and LeadershipmoniquecuiNo ratings yet

- 14 How To Ensure EthicsDocument8 pages14 How To Ensure EthicsJohn AlukoNo ratings yet

- Uu Mpa 7030 ZM 15336.Document14 pagesUu Mpa 7030 ZM 15336.edwardmabay484No ratings yet

- Advance Ethical Practices in Human Resource Management: A Case Study of Health Care CompanyDocument9 pagesAdvance Ethical Practices in Human Resource Management: A Case Study of Health Care CompanyGihane GuirguisNo ratings yet

- Effective Ethical ManagementDocument24 pagesEffective Ethical ManagementAre HidayuNo ratings yet

- Ethics Management in Libraries and Other Information ServicesFrom EverandEthics Management in Libraries and Other Information ServicesNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Unethical Leadership Issues, Cases, and Dilemmas With Case StudiesDocument8 pagesEthical and Unethical Leadership Issues, Cases, and Dilemmas With Case StudiesSumaira SaifNo ratings yet

- Adva Acc 1Document17 pagesAdva Acc 1Hamza AneesNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Managing Ethics in The Workplace1Document2 pagesBenefits of Managing Ethics in The Workplace1api-226538958No ratings yet

- Q3 - Module 2 Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocument11 pagesQ3 - Module 2 Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityCatherine CambayaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Manger and Ethical BehaviorDocument8 pagesOrganizational Manger and Ethical BehaviorFaisal AwanNo ratings yet

- 2 Core Principles of Fairness Accountability and TransparencyDocument28 pages2 Core Principles of Fairness Accountability and Transparencyrommel legaspi67% (3)

- Ethics Unit I NotesDocument43 pagesEthics Unit I NotesscubhaNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan Kelembagaan & Kapasitas Sektor PublikDocument24 pagesPengembangan Kelembagaan & Kapasitas Sektor PublikFahmi Rezha100% (1)

- A Framework of Rules Management Accountability The Ethical Environment Ethics in Organisations Accountants and EthicsDocument12 pagesA Framework of Rules Management Accountability The Ethical Environment Ethics in Organisations Accountants and EthicsUmar FarooqNo ratings yet

- Awards For CSDocument1 pageAwards For CSAbhishek MishraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Good Governance and Code of EthicsDocument31 pagesChapter 3 - Good Governance and Code of Ethicscj.terragoNo ratings yet

- Values Is Caught Rather Than Taught, (Elaborate) : Teach, Enforce, Advocate and ModelDocument5 pagesValues Is Caught Rather Than Taught, (Elaborate) : Teach, Enforce, Advocate and ModelArlea AsenciNo ratings yet

- Ethical LeadershipDocument15 pagesEthical LeadershippisabandmutNo ratings yet

- Order 3653731Document5 pagesOrder 3653731ookochrisphineNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Social Responsibility in International Business: Chapter ObjectivesDocument13 pagesEthics and Social Responsibility in International Business: Chapter ObjectivesIzza Arissa DamiaNo ratings yet

- Chap 13Document21 pagesChap 13Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 4Document18 pagesChap 4Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 8Document18 pagesChap 8Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 14Document17 pagesChap 14Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 6Document16 pagesChap 6Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 5Document20 pagesChap 5Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 11Document18 pagesChap 11Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 16Document18 pagesChap 16Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 7Document18 pagesChap 7Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 12Document17 pagesChap 12Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 - Teaching The Theory and History of The Nonprofit SectorDocument18 pagesChap 2 - Teaching The Theory and History of The Nonprofit SectorQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 10Document16 pagesChap 10Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Team 2 - Canada 1Document16 pagesTeam 2 - Canada 1Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- LF5002 Ebook French Level 2Document109 pagesLF5002 Ebook French Level 2Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- ChecklistforStudents (NBSWSDeg)Document1 pageChecklistforStudents (NBSWSDeg)Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Chap 9Document19 pagesChap 9Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Color Palette ProposalDocument5 pagesColor Palette ProposalQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- Company of Choice - PWC (Accounting Firm)Document8 pagesCompany of Choice - PWC (Accounting Firm)Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- S12 Text AnalyticsDocument15 pagesS12 Text AnalyticsQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- Health Insurance Coverage For HospitalisationDocument7 pagesHealth Insurance Coverage For HospitalisationQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- CheatSheet PA2Document2 pagesCheatSheet PA2Quang Huy100% (1)

- S12 Web ScrapingDocument13 pagesS12 Web ScrapingQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- 2022 APU UG Handbook Outside Japan 2 EDocument42 pages2022 APU UG Handbook Outside Japan 2 EQuang HuyNo ratings yet

- Doubts Raised On The Validity of Construction and Payment GuaranteesDocument26 pagesDoubts Raised On The Validity of Construction and Payment Guaranteesanon_b186No ratings yet

- Sanctions As WarDocument411 pagesSanctions As WarcyberbombermanNo ratings yet

- NVMMP ApplicationDocument1 pageNVMMP ApplicationForNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-13876Document2 pagesG.R. No. L-13876Bluebells33No ratings yet

- Statement 2020 04 10Document6 pagesStatement 2020 04 10Brenda100% (1)

- Andhra HC M - Patamata Seshagiri Rao vs. Pamidimukkala Sree 1998 - Suit For Declartion Without Cancellation MDocument8 pagesAndhra HC M - Patamata Seshagiri Rao vs. Pamidimukkala Sree 1998 - Suit For Declartion Without Cancellation MPritam NaigaonkarNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Intelligence Led PolicingDocument8 pagesThesis On Intelligence Led Policingwbrgaygld100% (2)

- Criminal CourtsDocument9 pagesCriminal CourtsKelvine DemetriusNo ratings yet

- Harihar Prakash Chaturvedi, Member (J) and Manorama Kumari, Member (J)Document10 pagesHarihar Prakash Chaturvedi, Member (J) and Manorama Kumari, Member (J)Ashhab Khan100% (1)

- NACTA Annual Report 2019 FinalDocument71 pagesNACTA Annual Report 2019 FinalQasim Javaid BokhariNo ratings yet

- IPL Module - V1Document95 pagesIPL Module - V1Noreen RicoNo ratings yet

- JOMC393-Final Paper - Gender Diversity in The WorkplaceDocument9 pagesJOMC393-Final Paper - Gender Diversity in The WorkplaceIsaiah WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Filipino Social ThinkersDocument20 pagesFilipino Social ThinkersRegine AndresNo ratings yet

- Board Reso FinalDocument2 pagesBoard Reso Finaljalefaye abapoNo ratings yet

- Summary-Mrs. Shehla Zia Vs WAPDA: Syed Ijlal Haider ERP 13309 Course: Legal and Regulatory Environment For BusinessDocument1 pageSummary-Mrs. Shehla Zia Vs WAPDA: Syed Ijlal Haider ERP 13309 Course: Legal and Regulatory Environment For BusinessSyed Ijlal HaiderNo ratings yet

- Pearly Beach Trust V Registrar of Deeds 1990 (4) Sa 614 (C)Document3 pagesPearly Beach Trust V Registrar of Deeds 1990 (4) Sa 614 (C)Banele BaneNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Freedom of Speech and International CommunicationDocument6 pagesGroup 2 Freedom of Speech and International CommunicationellaNo ratings yet

- Future Tenses: Class 106 / B1Document42 pagesFuture Tenses: Class 106 / B1Yiğit Kaan ÜnalNo ratings yet

- CH 1.taxationDocument18 pagesCH 1.taxationSajid AhmedNo ratings yet

- Salvation Army Federal LawsuitDocument36 pagesSalvation Army Federal LawsuitRobert GarciaNo ratings yet

- 4 Cmi Prmdmi160309Document10 pages4 Cmi Prmdmi160309Collblanc Seatours Srl Jose LahozNo ratings yet

- Revised Alternative Proposal - 4 July 2022Document10 pagesRevised Alternative Proposal - 4 July 2022RyanNo ratings yet

- ICARE Preweek RFBT Preweek 2Document12 pagesICARE Preweek RFBT Preweek 2john paulNo ratings yet

- XI C Worksheet It's A CrimeDocument3 pagesXI C Worksheet It's A CrimeRoxana Dumitrascu-DascaluNo ratings yet

- The Champion Legal Ads: 06-29-23Document54 pagesThe Champion Legal Ads: 06-29-23Donna S. SeayNo ratings yet

- Roy, FTS IcaiDocument176 pagesRoy, FTS IcaiPriyanga TNo ratings yet

- Zvanja Na EngleskomDocument1 pageZvanja Na EngleskomPeter PetrovickNo ratings yet

- Bihar TouristDocument5 pagesBihar TouristAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Legal MaximsDocument42 pagesLegal MaximsRaajashekkar ReddyNo ratings yet

- Solution To Module 9Document14 pagesSolution To Module 9Jeeramel TorresNo ratings yet