Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dalvi EconomicAnalysisLibel 2008

Dalvi EconomicAnalysisLibel 2008

Uploaded by

druthibarbie23Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dalvi EconomicAnalysisLibel 2008

Dalvi EconomicAnalysisLibel 2008

Uploaded by

druthibarbie23Copyright:

Available Formats

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

Author(s): Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

Source: Eastern Economic Journal , Winter, 2008, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter, 2008), pp. 74-

94

Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20642394

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Palgrave Macmillan Journals is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Eastern Economic Journal

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\?s Eastern Economic Journal, 2008, 34, (74-94)

Tjv ? 2008 EEA 0094-5056/08 $30.00

www.palgrave-journals.com/eej

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

Manoj Dalvia and James F. Refalob

aC. W. Post Campus, Long Island University, 720 Northern Blvd., Brookville, NY 11548, USA.

E-mail: mdalvi@liu.edu

California State University, 5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90032, USA

This paper examines the welfare implications of different libel law standards as applied to

newspapers in publishing stories. Our work extends the current literature by permitting

private and public incentives to deviate, giving rise to an agency problem, and by

formulating a two-stage decision model based on a story's expected value. We show that

the negligence standard provides incentives for the agent to take actions, merely to insure

itself against liability. This results in a deadweight loss to society. We also show that both

standards can be socially inefficient; however, correction using policy tools under strict

liability places a lower informational burden on policy makers, than does the negligence

standard.

Eastern Economic Journal (2008) 34, 74^94. doi.T0.1057/palgrave.eej.9050003

Keywords: agency; welfare; externality; negligence; liability; decision; deadweight loss;

subsidy; expected value

JEL: D61; D62; D81; K00

INTRODUCTION

This paper examines the welfare effects of different libel law standards as applied to

the publication of news stories about public figures. Because of public (social)

externalities, not all benefits or costs stemming from publication accrue to, or are

borne by, the newspaper. As a result of these distortions, the socially optimal

solution is unlikely to obtain.

The paper models the application of libel law by assuming that the newspaper's

decision to publish is determined by the expected liability (costs) arising from

publication of false stories, where its ability to mitigate some of the costs depends on

the applicable liability standard. We show that compared with strict liability, the

current standard governing libel law ? termed "negligence" ? leads to greater

publication costs for stories that are likely to be true and potentially increased

publication of stories that are likely to be false. This result is due to additional

liability protection provided by negligence, enabling a newspaper to "insure" against

liability.

We also show that an implicit agency problem exists between the newspaper

and society under both standards, and determine conditions for which the

social optimum can be consistently attained under strict liability, when using

conventional policy tools. We demonstrate that the negligence standard cannot be

adjusted in a similar manner. Finally, we provide other applications for this

modeling approach.

Prior to 1964, the legal rule governing libel in the United States was a "strict

liability" standard, under which a newspaper would be liable for all damages caused

to someone's reputation by any story that was not provably true.1 In its decision of

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo vi/

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law *7tV

75

New York Times v. Sullivan,2 the Supreme Court ruled that "a public official cannot

recover damages for a defamatory falsehood unless he proves that the statement was

made with "actual malice," ? that is "with knowledge that it was false or with

reckless disregard of whether it was false or not."3 It thereby reduced the range of

stories for which a newspaper could be found liable. In 1967, the Supreme Court

extended this protection to stories about public figures.4 Thus, a negligence-style

standard now governs libel suits brought by public officials or public figures.5

The motivation for this paper is to analyze implications for public welfare of these

different liability standards in the presence of public externalities. Libel is an

example of a "single activity accident" [Brown 1973; Diamond 1974], such that the

actions of a newspaper damage an individual.6 For single activity accidents, a strict

liability standard in the absence of other externalities is generally efficient [Shavell

1980; 1987]. Such models examine cases in which the only externality from an

activity is the harm done to a third party.7 However, publishing news about public

issues is deemed to entail a positive externality.8 The concern with a strict liability

standard for libel is a potential chilling of publication and concomitant reduction of

this externality.9 If publishers internalized all benefits from their activities and the

only distortion was the negative externality from libel, this would not be of any

concern. Since conventional tort models typically assume the party will internalize

all benefits and costs other than third-party damages, it is important to consider

some deviation from those assumptions in order to assess whether the New York

Times v. Sullivan standard is appropriate.

The model in this paper will allow for the possibility that, absent any libel, the

social value of publishing differs from the private incentive.10 We do this by

assuming that the newspaper pursues policies that maximize expected value, and

that the costs and benefits from publication differ from those of society. Such an

assumption implies that a strict liability standard, by itself, does not result in the

social optimum. However, we show that in theory we can adjust the strict liability

standard using policy tools so that the problem solved by the publisher is

proportional to that needed to maximize public welfare. In contrast, the negligence

standard will fail to attain the social optimum even with the use of policy tools.

We extend the existing liability literature and study the distortions caused by

liability rules in a two-stage decision model where the newspaper has the option to

obtain further information regarding the truthfulness of a story, and we allow

abandonment of the activity.11 The former permits a revision of the expected value

of a story; the latter allows a story to be pursued that would otherwise not be

sufficiently plausible to publish under a strict liability standard. Permitting

investigation also allows us to examine the qualitative differences between the two

liability standards, namely that under negligence, investigation permits a publisher

to inure itself against liability. Using the two-stage model we are able to define

regions governing the actions of the publisher based on the ex ante (or perceived)

probability that a story is true.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses the

details of the model and derives the probability boundaries that are central to the

model and govern the publishing decisions of the newspaper. The subsequent section

derives the welfare equation and examines the deviation from the social optimum

created by the agency problem. This section also develops the conditions under

which policy tools can be used to correct for agency, and discusses policy

implications. The penultimate section provides applicable extensions. The final

section presents the conclusions.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\Ls Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

VrV An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

76

THE MODEL

General setup and assumptions

General setup

Assume that a newspaper has access to a number of newsworthy stories, and that

each has a perceived probability of being true.12 The newspaper has three potential

actions with regard to each story: publish without investigation, investigate, or kill.

If the newspaper chooses to investigate, then it will publish or kill the story based on

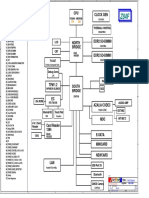

the results of the investigation. The decision tree of the newspaper is given in

Figure 1. The newspaper is assumed to face one of two liability standards: strict

liability or negligence. To determine the chosen action, we compute the expected

value of the actions given the liability standard, and then determine the range of

probabilities over which each action is optimal for the newspaper. We then compare

standards by comparing the range of probabilities over which the actions are taken.

Assumptions and notation

Each story is assumed to have a probability p of being true, where f(p) is the

corresponding distribution of p for stories being considered by the newspaper.13 If

the newspaper publishes a true story, it obtains benefit v > 0. If it publishes a false

story, it suffers a loss d > 0, which is independent of any liability. We can think of the

benefits and losses as stemming from increases/decreases in circulation or

advertising revenue that can be attributed to the publication of a story. If the

newspaper publishes a false story, it may also be liable for damages to the individual,

Dh depending on the liability standard.

The newspaper has the option of investigating a story for a cost C. The

investigation will signal that a story is "true" or "false," and based on that signal,

the newspaper chooses to "publish" or "kill" the story.

Investigation is assumed to be imperfect, and can yield an incorrect signal about

the truth of a story. Let a be the probability that the investigation will signal that a

true story is "false," and ? be the probability that the investigation will signal that a

false story is "true." Assume that a<0.5 and that ?<0.5.

The first standard we consider is termed "strict liability," where the newspaper

incurs liability damages if it publishes a false story. The second standard is termed

"negligence."14 The Supreme Court's definition of negligence is "with knowledge

that [the story]... was false, or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not."

To reflect this in our model, the newspaper incurs liability damages under negligence

Publish Publish

Kill Kill

Figure 1. Actions of the newspap

newspaper. The newspaper can pub

updates its probability, and then d

regime that confronts the newspape

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo vj>

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law "?jV

77

only when it publishes a false story when the investigation has signaled that it is false,

or publishes a false story that has not been investigated.15 The newspaper does not

incur a liability if it publishes a false story that it has investigated when the

investigation has signaled that the story is true.

Newspaper actions

Since the newspaper receives benefits from publishing a true story and incurs

damages when publishing a false story, the expected value of each story is a function

of the liability standard, the story's probability, and the action taken. Thus, given a

liability standard and a probability, the newspaper must decide whether to publish

without investigation, investigate, or kill a story, in order to maximize the story's

expected value:

(1) V(p) = Max{EV(Publish W/O), EV(Kill), EV(Investigation)}

The intuition is straightforward. At date 0, the newspaper takes the action yielding

the maximum expected payoff for a story with a probability p of being true. For

example, a decision to publish without investigating means that the expected payoff

from that action is greater than the expected payoff from killing or investigating (less

the cost of investigation).

To determine the range of p over which each action is optimal, we compute two

boundary equations (probability bounds): a lower bound for p along which the

newspaper is indifferent between investigating and killing a story, and an upper bound

along which the newspaper is indifferent between investigating and publishing a story.

These boundaries are determined by equating the expected values for the alternative

actions, and solving for the corresponding p. The newspaper thus kills all stories with

p below the lower bound, and publishes all stories with p above the upper bound. It

investigates all stories with p between the two bounds.

Regardless of the liability standard, if the newspaper kills a story, then there are

no expected benefits, damages, or investigation costs: the expected value is 0.

Likewise, regardless of standard, if it publishes without investigation, there are no

investigation costs, so the expected value is the expected benefits of publishing a true

story less the expected damages from publishing a false story:

(2) EV(Publish W/O) ? pv - (\ -p)(d + Z>/)

However, because the negligence standard provides liability protection when stories

are investigated, and strict liability does not, the expected value of investigating a

story (and corresponding probability bounds) must be determined contingent on a

standard. The next two sections develop respectively the expected value of

investigation subject to strict liability and negligence, and compute the correspond

ing probability bounds determining the newspaper's actions.

Strict liability

Under a strict liability standard, a story will only be published after investigation

when the investigation signals that the story is true.16 Thus, the expected value from

investigation is the expected benefit from publishing a true story, less the expected

damages from publishing a false story, less the cost of investigation (for proof, see

appendix; payoffs for the decision tree are illustrated in Figure 2):17

(3) EV^(Investigation) = p(\ - a)v - (1 -p)?(d + D7) - C

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\1/ Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

VfV An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

78

pv - (1 -p)(d + Dj) (I- ot)p(v -O- ?(l-p)(d + D7 - O

0 (ocp + (l-?)(l-p))(0-C)

Figure 2. Actions of the newspaper. There are three potential actions for the newspaper under strict

liability. The actions are kill the story without investigation, publish without an investigation, or

investigate and publish if the investigation signals that the story is true. The payoffs to the newspaper for

these actions are illustrated by the following diagram.

Publish Without

Investigation

Pc>c's

Figure 3. Actions of the newspaper under strict liability. The figure summarizes the optimal actions of the

newspaper regarding a story with a probability (/?) of being true under a strict liability standard. The

newspaper's action is determined by the relationship of p to the probability bounds pj and p". No

investigation occurs for C>CS".

To establish the lower bound for which an investigation is undertaken (/?/), we

equate (3) with the expected value of "killing" the story (zero), and solve for the

probability:

(4) p{\ - a)v - (1 -p)?{d + /)/)- C = 0

Likewise, to obtain the upper bound on p for which investigation is optimal (p"\ we

equate (2) with (3) and solve for the corresponding probability:

(5) pv - (1 -p)(d + Dj) = p(\ - a)v - (1 -p)?(d + Dj)C

When a story's probability lies below pj, it is not sufficiently plausible to

investigate given the expected costs and benefits, and is immediately "killed" by the

newspaper. Above the story is so credible that the newspaper publishes the story

without investigation. The reason is that the cost of investigation exceeds the

expected damages from publishing a false story; thus, it is economically inefficient to

investigate. Finally, in the region between pj and /?/, an investigation is conducted.

The story is "killed" if the signal is false, and it is published if the signal is true.18

Figure 3 summarizes the actions of the newspaper under strict liability.

Note that pj slopes upward in C ? as investigation costs increase, so does the

minimum p for which EV(Investigatiori) > 0. Likewise, p" slopes downward in C

because the maximum p for which EVs(Investigatiori) > EV(Publish W/O) declines.

Because these bounds converge, there is an upper bound on the cost of investigation

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

79

(C/), beyond which it is economically sub-optimal to investigate any story. C" is

determined by equating pj with p", and solving for C.

The optimal action under strict liability is summarized in the following

proposition:19

Proposition 1 Assume that the newspaper is subject to a strict liability standard;

then there is a lower bound, pj (that is positively sloped in C), and an upper

bound, p" (that is negatively sloped in C), such that the newspaper will: kill

a story when p<ps\ publish the story without investigation when p>ps", and

investigate the story and publish only if the investigation signals the story is true,

whenPs <P<Ps'- Defining C" as the value of C at which pj andp" converge to

a single boundary Pc>c"si when C/, the newspaper will publish all stories for

P>Pc>c"s and kill all stories for p^Pc>c"s

Proof See appendix.

Negligence

The qualitative results under a negligence standard are similar: there is, however, a

significant difference. Because the newspaper is absolved of liability when it

investigates and receives a signal that the story is true, two more probability

boundaries exist (defining a fourth range of p) for which the newspaper has

economic incentives to investigate, merely to insure against potential liability. This

region only exists when investigation costs are low.

Under negligence the expected value from investigating and publishing after an

investigation signals the story is true is given by20

(6) EVn(Investigation) = p(\ - a)v - (1 - p)?(d) - C

Thus like strict liability standard, there is a lower bound (p?) and an upper

bound (pn% under negligence, that determine whether a story is killed, investigated,

or published. The lower bound is obtained by equating equation (6) with the

expected value of killing the story. The upper bound is found by equating equations

(6) and (2).

As shown in Figure 4, all stories with a probability less than pn' are killed without

investigation. When investigation costs exceed a threshold value C", stories with

Publish Without

Investigatijon

Publish

Regarpless

Pete's

Figure 4. Actions of the newspaper under negligence. The figure summarizes the optimal actions of the

newspaper regarding a story with a probability (p) of being true. The newspaper's action is determined by

the relationship of p to the four probability bounds Pn,pn-ib"> p" > and Pw> andthe cost ofthe investigation

(O relative to the threshold value C. No investigation occurs for C>C?".

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

Publish)

if True I

Figure 5. The "Insurance Effect." If investigation costs exceed C the newspaper on

that require a true signal to be published. Thus, the newspaper only publish

investigation, or that have been signaled to be true. The boundary pn" separates tho

the cost is below C, it will investigate stories that it is certain to publish, betwee

stories with probabilities above p?" are published without investigation, the newspap

region between pn" and pn'" only to gain liability protection.

probabilities between pnf and pn" are investigated and published if

signals that the story is true, and stories with probabilities gre

published without investigation. The bounds derived under neglig

those of strict liability (and, in fact, are wider), but the pap

qualitatively the same.

However, unlike strict liability, when the cost of investigation is

an additional region where the newspaper investigates and publi

the investigation signal. This region is defined by the boundspn,f/

in Figure 5.

Since stories with probabilities greater than pn" are published w

tion, the newspaper investigates a story in the region betwee

because the cost of investigation is less than the expected liabili

publishing a false story,21 and because it can eliminate that liabilit

and receiving a true signal. This sole benefit causes the newspap

stories in this region to "purchase" the liability protection

"insurance" value. The intuition is that the newspaper "buys"

insurance is "cheap."22

In the region abovepn-ib" and belowpn", the newspaper publish

investigation results for a different reason. It publishes a story w

because the marginal expected benefits from publishing on a false

marginal expected damages.23

The expected value of investigating and publishing regardless of

signal is given by

(7) EVn(Publish Regardless) =p(l ? oc)v ? (1 -p)?(d)

+p*v - (I - p)(l - ?)

(d + ?>/)- C

The expression for pn-ib" is found by equating equations (6)

solving for p. The expression for pnfff is similarly found by equatin

(2), and solving.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \Lf

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law */T\

81

Derivation of these critical values is presented in the appendix; the results are

summarized in the following proposition:

Proposition 2 Assume that the newspaper is subject to a negligence standard.

There is an upper bound on the cost of investigation (C?"), beyond which it is

sub-optimal to investigate. There is also a lower bound (C < C?"), below which

the newspaper will investigate stories that it will subsequently publish regardless

of the investigation's outcome. Assume C<C/; there are four probability

boundaries pn' <pn" ^pn-ibf" <pnf", such that:

(1) The boundariespn-ib" andpnm converge at C, which is wherepn-ib" ends and

p?" begins. Likewise, pnf and pn" converge at Cnff.

(2) The newspaper will kill all stories when p<pnf.

(3) If C<C, the newspaper will: publish a story without investigation, for

p>Pn", investigate and publish regardless of investigation results, for

Pn-ib1<p<p,n', investigate and publish (only) when the investigation indicates

the story is true, for pnf <p<pn_ibm.

(4) If C <C<Cn", the newspaper will: publish a story without investigation, for

p>Pn\ investigate and publish (only) when the investigation indicates the

story is true, for p? <p<pn".

Proof See the appendix.

Comparison of standards

Figure 6 compares the actions of the newspaper under the two standards. The

investigation region for negligence completely contains the investigation region for

strict liability. This is because investigation is more valuable under negligence:

investigation is imperfect, and the newspaper is able to eliminate the liability from

publishing a false story by investigating and obtaining a true signal. As a result,

relative to strict liability, the lower bound shifts down because the increased value of

investigation makes it economically feasible to investigate stories with lower

c c; c;

Figure 6. Comparison of liability standards. The investigation

a subset of the region under negligence where stories are i

negligence,pn-ib" andpn'" are an upper bound to the region

if true, and p? is the corresponding lower bound. The upper an

standard are p" and pj, respectively. C and C" are always str

or less than, C.

Eastern Economic Journal

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

vi/ Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

VpT An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

82

probabilities.25 Consequently, there is increased publication of lower probability

stories. (Note: As will be shown, this does not necessarily lead to lower societal

welfare, which is also sensitive to parameter values and distributional assumptions

about p.)

Likewise, the upper bound shifts up under negligence, because investigation

provides liability protection beyond merely discriminating between true and false

stories, which is the sole function of investigation under strict liability. Thus, the

newspaper investigates higher probability stories to gain this added liability

protection. Indeed, when investigation costs are less than C, there is a region

under negligence in which stories are investigated solely to obtain insurance, since

these stories will be published regardless of the investigation results. Thus, for any

set of stories, more low probability stories will be investigated and published, and

more high probability stories will be investigated, under negligence.26 Proposition 3

summarizes these results:

Proposition 3 For any given set of parameters pertaining to a story (v, d, Dh a, ?,

and C), Cn > C". Likewise, the relationship between the probability bounds for

strict liability and negligence can be expressed:

For C<C: thenPn <pj<p"^Pn-ib"<Pn", withpnf" converging topn-ib" at C.

For C <C<Cn": thenPn <Ps <Ps <Pn \ withpj andp" converging at C/, and

Pn and pn converging at Cn".

Proof See the appendix.

WELFARE ANALYSIS

The welfare optimum

Welfare is the net benefit (or loss) to society from publication of a story. If a story is

true, society receives a benefit (V> v). If a story is false, society receives no benefit;

the cost to society is the sum of the damage to society (Ds) and the damage to the

individual (Z)7).27 If an investigation is conducted, the society incurs a cost (Q,

whether or not the story is published.28 The expected welfare is the expected value to

society of a true story less the expected cost to society from publication of a false

story, and any investigation costs.

If society internalizes all the costs and benefits from publishing a story, strict

liability is efficient [Shavell 1980; 1987]. Thus, it is under strict liability that society

computes the lower and upper boundaries (pf and p") to solve for the social

optimum. These boundaries are derived in the same manner as those of the

newspaper under strict liability, except that d?Ds and v=V, and they determine

whether society kills, researches, or publishes a story without research. This is

summarized by the following proposition:

Proposition 4 To maximize expected welfare, society computes lower and upper

probability bounds p' and p", respectively. Society would kill all stories when

p<p\ publish a story without investigation when p>p'\ and investigate and

publish only when the investigation indicates that the story is true, forp' >p>p".

Proof See appendix.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \Ay

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law "?TV

83

The expected welfare is

(8) W = j[p{\-*)V-{\-p)?{Ps

p' + Di)-C]f{p)dp

l

+ P"j [pV-il-pHDs + DMfWdp

The first integral is the expected utility from a story that is investigated

and published, p is the probability that the story is true, and 1-a is the probability

that the investigation has correctly signaled that the story is true, l?p is the

probability that the story is false, and ? is the probability that the investigation has

incorrectly signaled that the story is true. The distribution of p is f(p).29 Investigation

costs are incurred over the region p^{p\p") regardless of whether a story is

published.

The second integral is the expected utility from stories that are published

without investigation. If the story is true, society receives benefit V with a

probability p. If a story is false, society incurs collective damages of Ds + Dj

with a probability l?p. Since no investigation has been conducted, no costs are

incurred.

The expected welfare equation differs from the expected value of a story to a

newspaper under strict liability,30 and under negligence. Crucially, the bounds of

integration (pf and p") ? which are the probability bounds ? differ from those of

the newspaper under either liability standard. Since it is the bounds chosen by the

newspaper (not society) that determine which stories are killed, investigated, or

published without investigation, there will be a departure from publication policies

that maximize expected welfare.31

Inherent inefficiencies of agency

Society faces an agency problem because the newspaper computes probability

boundaries that are different from those of society (with the exception of footnote

30). Under strict liability, society's expected welfare is computed by substituting the

newspaper's upper and lower boundaries for its welfare maximizing boundaries.

Sub-optimality results and gives rise to the agency problem if the newspaper's

bounds do not equal pf and p".

Under negligence, the problem is more complex; because the probability bounds

used by the newspaper are dependent on C, it is divided into two regions: C^C and

C<C. If OC, (then like strict liability) pnf and pn" are substituted for society's

lower and upper bounds, and a loss of welfare results if the bounds are not equal in

value to those computed by society.32

However, if C<C, the newspaper carries out an additional action that society

would not ? investigate and publish regardless of the result. It will do so between

the boundaries pn-ib" and pnf". This action is sub-optimal because society

internalizes all costs and does not benefit from the additional liability protection

received by the newspaper. Hence, investigation when publication is certain provides

no additional benefit to society, but creates additional costs.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

*Manoj AnDalvi andAnalysis

Economic James F.Law

of Libel Refalo

84

The resulting welfare equation is

(9) Wn,c<c [p(l _ a)v - (1 -p)?(Ds + D,) - C]f(p)dp

+ / [pV-V-pKDs + DMmdp

-C

The third term of this equation reflects the addition

investigating a story that will be published with certainty,

always less than the social optimum. The reason is, to maxim

of integration for the first two terms of (9) must equal the bou

expected welfare equation, for example Pn?p1 and pn_

negligence, when C<C, we have (8) less the third term

expected welfare is always sub-optimal. A derivation of

appendix.

Welfare comparison

The social optimum does not obtain when boundaries on the welfare equation

(under strict liability or negligence) do not equal p' and p". Thus, specific parameter

values and distributional assumptions (about p) are necessary to determine which

standard provides the greatest expected welfare for a given story. Comparison of

Figures 7a to 6d, and 8a-c, illustrates the conditions for which each standard is best

suited; the figures map the difference in welfare (between standards) as a function of

the indicated axis variables. To avoid introducing additional non-linearities, we

assume that p is uniformly distributed. In general, parameter values are permitted to

range over the unit interval, so as to represent a fraction of the value to society of a

true story (V= 1), as a benchmark.33 Figures 7b and 8b/c contrast these benchmarks

with that for a high-value story (V=2).

Light gray indicates that society's welfare from strict liability equals or exceeds

that of negligence, and dark gray indicates that it is less. Contrasting Figures 7a

and b reveals that higher values of V, Ds (relative to Z>7), and proportional increases

in v and d, lead to a greater range of error rates over which strict liability provides

higher welfare. Figure 7c shows that when v is low relative to d, negligence is

generally superior. Likewise, higher investigation costs tend to favor the negligence

standard (see Figure 7d). Note that in the presence of high investigation costs, high

type 1 and type 2 error rates (high a and ?) result in no investigation being

conducted under either standard. The ravine (in Figure 7d), where negligence is

clearly superior, is bounded in by C" to the right and Cn" to the left. Negligence is

distinctly superior in the ravine, because to the left of C" no investigation occurs

under strict liability, and reflects the greater value of investigation to the newspaper

under negligence.

Comparison of Figures 8a-c reinforces these conclusions. Figure 8b shows the

effect of an increase in V\ Figure 8c illustrates the impact of higher investigation

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law "TrV

85

a Strict Liability Minus Negligence b Stdct Liability Minus Negligence

C Strict Liability Minus Negligence d Strict Liability Minus Negligence

Figure 7. (a-c): Welfare comparison in <x-? space. The difference in welfare between the strict liability

and negligence standards, for p uniformly distributed between zero and one. The parameters (K, Dh C, v,

d) for each graph are (1, 0.5, 0.01, 0.3, 0.3), (2, 0.2, 0.01, 0.4, 0.4), (2, 0.2, 0.01, 0.2, 0.4), and (2, 0.2, 0.1,

0.4, 0.4), respectively. Ds is computed as \-D/, thus, total damages to society equal unity. Light gray

indicates that welfare from strict liability equals or exceeds that under negligence; dark gray indicates that

it is less.

costs ? for either small values of v or d, no investigation is conducted under either

standard.34 In summary, the region over which strict liability is welfare superior to

negligence increases with V and the ratio of Ds to Dj. The region declines as

investigation costs increase.

Use of policy tools and the advantage of strict liability

Without the use of policy tools, the social optimum cannot be assured for either

standard. However, under strict liability there exists an investigation subsidy and

scaling of damage award for which social optimality is consistently achieved, based

solely on V, Ds, Dh v, and J, and does not require knowledge of the investigation

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\1/ Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

"?rV An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

86

a Strict Liability Minus Negligence b Strict Liability Minus Negligence

C Strict Liability Minus Negligence

Figure 8. (a-c): Welfare comparison in v?d space. The difference in welfare between the strict liability

and negligence standards, for p uniformly distributed between zero and one. The parameters (K, Dh C, a,

?) for each graph are (1, 0.5, 0.01, 0.2, 0.05), (2, 0.2, 0.01, 0.2, 0.05), and (2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.05),

respectively. Ds is computed as \-Df; thus, total damages to society equal unity. The light gray region

indicates that welfare from strict liability exceeds that under negligence; the dark gray indicates that it is

less.

error rates, a and ?.35 This solution is not available for negligence and is

independent of distributional assumptions.

Proposition 5a Under strict liability, the socially optimal subsidy and liability

scaling is (l-v/V)C and [v/V(Ds + Dfi-dfilD^ respectively.

Proof See the appendix.36

Under the negligence standard, such a correction is impossible: (1) for C<C\ the

social optimum can never be obtained due to the deadweight loss indicated in (9), (2)

for C^C, the value of a and ? must be known to determine the socially optimal

subsidy and liability scaling. These values place increased informational burden on

policymakers. The latter problem is summarized by the following proposition:

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \i/

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law *?rV

87

Proposition 5b Assume a negligence standard, with C^C; the subsidy and

damage scaling that are required for socially optimal publication are sensitive to

values of a and a.

Proof See the appendix.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper studies the decision-making process of a newspaper in publishing a story

about public officials under two liability regimes. It has been established by previous

research that if private and social benefits and costs are equal, then strict liability is the

socially optimal standard. However, we find that because the newspaper does not

internalize all public externalities, neither liability standard will reliably attain the

social optimum, except under special conditions. This deviation in benefits also leads

to an implicit agency problem between the newspaper and society.

We show that under negligence, the newspaper will investigate more low and high

probability stories because of the liability protection that standard provides. This

leads to two inefficiencies: (1) the newspaper may have incentives to investigate and

publish very low probability stories, merely because of its ability to protect itself

from liability; (2) when investigation costs are below a threshold, the newspaper has

incentives to investigate stories that it is certain to publish, merely to gain the

additional insurance value. The latter inefficiency results in a deadweight loss to

society. We also show that by partly subsidizing investigation costs and by scaling

the liability damages, the social optimum can be reliably obtained under strict

liability, without knowledge of investigation error rates. In contrast, we show that

the negligence standard requires knowledge of all parameters, thereby creating

increased informational burden for policymakers.

Finally, one possible extension of the model is to allow investigation accuracy to

vary in terms of its cost. Likewise, the model does not permit investigation accuracy

to vary with likelihood that a story is true. Both extensions would require additional

parameterization. The model also ignores issues of risk aversion; risk aversion will

alter the probability bounds computed by the newspaper. Finally, the model

abstracts from issues of competition. Competition among newspapers for market

share is likely to alter publishing policies, by introducing strategic considerations

requiring a game-theoretic approach. This would be an interesting direction to

meaningfully extend the model.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gilbert Skillman and two anonymous referees for

substantially improving the quality of this paper. The first author acknowledges his

debt of gratitude to John Donaldson and Michael Salinger for their encouragement

and guidance. We would also like to thank Chris Stefanadis for his comments on the

paper. We accept responsibility for all the errors contained herein.

Notes

1. Simply for expositional convenience, we will refer to the potential tortfeasor as a newspaper. None of

the arguments are specific to that medium, however.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\j> Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

*?T\ An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

88

2. 376 US 254 (1964).

3. 376 US 254, 279-280 (1964).

4. Associated Press v. Walker, 388 US 130 (1967).

5. While "negligence," "gross negligence," and "actual malice" have different legal meanings, liability

standards based on them have the same basic structure. All three allow for a defense for publishing a

defamatory false statement. It is easier for a newspaper to avoid liability under a gross negligence

standard than under a negligence standard and still easier to do so under an actual malice standard,

but we view these differences as matters of degree.

6. Opportunities provided the individual to avoid the appearance of impropriety are (presumably) not a

serious consideration in formulating libel law.

7. Other examples of models that use the care-activity framework to study the incentives of the injurer

and the victim to reduce losses are: Green [1976]; Diamond [1974]; in the context of medical

malpractice ? Shavell [1978]; Simon [1982]; and Danzon [1990]; product liability ? Oi [1973]; Eppel

and Raviv [1978]; and obtain information about risk [Shavell, 1992].

8. In New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court said that a major consideration was the "profound

national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and

wide-open." 376 US 254, 270 (1964).

9. Hylton [1996], Posner [1998], and Cooter [2000] argue that when the newspaper publishes a story it is a

public good and are unable to capture the full value of the story it has published. Since they are unable

to capture the full social benefit of their publication, holding them strictly liable will result in a chilling

effect on speech.

Renas et al. [1983] develop a model of a profit maximizing newspaper and analyze how the newspaper

reacts to changes in the liability rules imposed on it. They argue that the newspaper will not behave in

a manner to optimize social welfare and analyze the second-best solutions that will prevail. Garoupa

[1999a, b] address the implications of the tort of libel on political corruption where the media is

powerful enough to influence the electorate.

10. Shavell [1997] studies the divergence between private and social motives to settle lawsuits. He argues

that the distortion arises because of litigation costs that are incurred by both parties, and suggests a

number of remedies to align the private and the social, including litigation subsidies, and fee shifting.

Spier [1997] examines the role of litigation subsidies, punitive damages, and allocation legal costs. Our

paper extends this area of research by exploring how liability standards give rise to distortions, and by

examining the use of policy tools to correct inefficiencies. Also see Calabresi and Klevorick [1985] and

Schwartz [1985].

11. In an effort subsequent to earlier versions of this paper, Oren Bar-Gill and Assaf Hamdani [2003] use a

Baysian approach to analyze optimal levels of verification under libel. Their approach is similar to

that used in an earlier version of this paper. They depart from us by studying optimal levels of

verification and by studying only strict liability. Their findings reinforce ours: policy tools are

necessary to ensure optimal investigation and publishing policies.

12. Hereon, we define this as a story's "probability."

13. The potential stories available to a paper in this model are assumed to be random and exogenous. A

natural extension of the model would be to allow the newspaper to make the population of potential

stories a function of the newspaper's expenditures.

14. We make the simplifying assumption that the courts enforce both standards perfectly. For an analysis

of tort law in which enforcement is imperfect, see Calfee and Craswell [1984]. Extending the analysis

here to allow for imperfect enforcement would be particularly desirable because the ambiguity of

"actual malice" is the basis of one of the major criticisms of the current doctrine. See, for example,

Epstein [1986].

15. We interpret "actual knowledge" that a story is false to mean that the paper investigates the story and

obtains information that it is false. We interpret "reckless disregard" for whether the story is true or

false to mean a failure to investigate.

16. Under strict liability, a newspaper is fully libel for Dr if a story is false, regardless of investigation

signal. Thus, it will not investigate a story that will be published regardless of the investigation result,

because the expected value resolves to equation (2), less the cost of investigation.

17. The first term is the expected benefit from publishing a true story: (1-p)v, multiplied by the

probability the investigation correctly signals that the story is true, 1?a. The second term is the

expected damages from publishing a false story: (\-p)(d+ Dj), multiplied by the probability the

investigation will incorrectly signal that the story is true, ?.

18. This result arises in all "value of information" problems. The paper only incurs the cost of

investigation if the outcome of the investigation affects its actions.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \1/

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law VtV

89

19. If investigation is too expensive, then there are no probabilities under which investigation is optimal.

The critical value for C is the investigation cost above which investigation does not occur. If C is above

that level, then there is a single critical probability that divides stories that are published without

investigation from those that are killed without investigation.

20. Because the newspaper is absolved of liability, equation (6) is equation (3) less the liability

damages, Dh

21. For example, C<(\-p)?(Ds).

22. The intuition for the "insurance effect" can be observed by adding (\-p)?DI-C, the expected

liability from publishing a false story after receiving a true signal less the cost of investigation (a net

add-back), to equation (2). This yields the expected value of investigating and publishing regardless ?

equation (7).

23. Add poLv-(l-p)(\~?)(d+Dj), the expected value for publishing despite a false signal, to the expected

value from publishing only on a true signal. Therefore, the newspaper publishes on a false signal so

long as pav-(\-p)(\~?)(d+Djy

24. The first two terms of this action are the expected value from investigating and publishing when the

investigation signals that the story is true. The third and fourth terms comprise the expected value

from investigating and publishing when the investigation signals that the story is false.

25. A newspaper, with a sufficiently low d, may have the perverse incentive to investigate stories that it

believes are false (have a low probability of being true), merely to obtain a signal exempting it from

liability. This may explain the behavior of some tabloids, whose circulation appears insensitive to

reputational damage.

26. The reason we differ with conclusions of the standard tort models (which find that negligence and

strict liability are equally efficient) is the imperfection of investigation, and that under negligence, the

newspaper is able to eliminate liability by investigating and receiving a signal that the story is true.

27. V includes the benefits to the newspaper, v, and Ds includes the damages to the newspaper, d, but

excludes/)/.

28. This is the same cost incurred by the newspaper.

29. Since the firm receives a number of stories, it has a prior probability about the truth of each story. We

assume that these prior probabilities are distributed over the interval [0,1].

30. Unless (strict liability only) the newspaper internalizes all costs and benefits to society, for example

v=V and d=Ds.

31. There are respective solution hyper-planes for strict liability and negligence (when C^C) that equate

the newspaper's boundaries with those of society. However, any departure from the required

parameter combinations defining that hyper-plane will result in a sub-optimal level of welfare. Under

negligence, if 0<C<C, optimality is never attained.

32. Structurally, the objective function in the welfare equation differs from that of the expected value to

the newspaper under negligence because society computes its expected welfare by internalizing all costs

? it must include individual damages Di if a false story is published. In contrast, the newspaper

eliminates this cost when it investigates and receives a true signal.

33. a and ? (representing the probability of type 1 and type 2 errors) are assumed to range from 0 to 0.5.

Ds = l?Dj, so that total damages to society always sum to one.

34. Because of perspective, Cn" is on the left and C" is on the right.

35. The intuition behind this subsidy and damage scaling is that the newspaper should bear costs and

damages in the same proportion to benefits as is borne by society.

36. If we can make the assumption that all stories have benefits and damages to the newspaper and society

in the same proportion, then the socially optimal subsidy and damage scaling are dependent only on

investigation cost: (\-K)C and K (respectively), where v/V=d/D = K.

References

Bar-Gill, Oren., and Assaf Hamdani. 2003. Optimal Liability for Libel. The Berkeley Electronic Press,

http://www.bepress.com/bejeap, in Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy 2, Issue. 1, Article 6.

Brown, John P. 1973. Toward an Economic Theory of Liability. Journal of Legal Studies, 2: 323-349.

Calabresi, Guido., and Alvin K. Klevorick. 1985. Four Tests of Liability in Torts. Journal of Legal

Studies, 14: 585-627.

Cooter, Robert D. 2000. The Strategic Constitution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Calfee, John E., and Richard Craswell. 1984. Some Effects of Uncertainty on Compliance with Legal

Standards. Virginia Law Review, 70: 965-1003.

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

90

Danzon, Patricia M. 1990. Alternative Liability Regimes for Medical Injuries. The Geneva Papers on Risk

and Insurance, 15(54): 3-21.

Diamond, Peter A. 1974. Single Activity Accidents. Journal of Legal Studies, 3: 107-164.

Eppel, Dennis, and Artur Raviv. 1978. Product Safety: Liability Rules, Market Structure, and Imperfect

Information. American Economic Review, 68: 80-95.

Epstein, Richard A. 1986. Was New York Times v. Sullivan Wrong? University of Chicago Law Review,

53: 782-818.

Garoupa, Nuno. 1999a. Dishonesty and Libel Law: The Economics of the "Chilling" Effect. Journal of

Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 15: 284-300.

_ 1999b. The Economics of Political Dishonesty and Defamation. International Review of Law &

Economics, 19: 167-180.

Green, Jerry. 1976. On the Optimal Structure of Liability Laws. Bell Journal of Economics, 7: 553-574.

Hylton, Keith N. 1996. A Missing Markets Theory of Tort Law. North Western University Law Review,

90: 977-1004.

Oi, Walter Y. 1973. Economics of Product Safety. Bell Journal of Economics, 4: 3-28.

Posner, Richard A. 1998. Economic Analysis of Law, 5th ed. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Law &

Business.

Renas, M.Stephen, Rishi Kumar, Charles J. Hartmann, and Donn G. Shankland. 1983. Toward an

Economic Theory of Defamation, Liability, and the Press. Southern Economic Journal, 50: 451^60.

Schwartz, Alan. 1985. Products Liability, Corporate Structure and Bankruptcy: Toxic Substance and the

Remote Risk Relationship. Journal of Legal Studies, 14: 689-736.

Shavell, Steven. 1987. Economic Analysis of Accident Law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Shavell, Steven. 1992. Liability and the Incentive to Obtain Information about Risk. Journal of Legal

Studies, 21: 259-270.

Shavell, Steven. 1980. Strict Liability vs Negligence. Journal of Legal Studies, 9: 1-25.

Shavell, Steven. 1997. The Fundamental Divergence Between the Private and the Social Motive to Use the

Legal System. Journal of Legal Studies, 26: 575-612.

Shavell, Steven. 1978. Theoretical Issues in Medical Malpractice, in The Economics of Medical Malpractice,

edited by S. Rottenberg, Vol. 178. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 35-64.

Simon, Marilyn J. 1982. Diagnoses and Medical Malpractice: A Comparison of Negligence and Strict

Liability Systems. Rand Journal of Economics, 13: 170-180.

Spier, Kathryn E. 1997. A Note on the Divergence Between the private and the Social Motive to Settle

Under a Negligence Rule. Journal of Legal Studies, 26: 613-622.

Appendix

DERIVATION OF EQUATION (3)

Let / denote the investigation signal and let S denote whether the story is true (T) or

false (F). If the newspaper investigates, the probability that it receives a true

investigation signal is

P(I = T) =P{I = r|S = T) P{S = T)

+ P{I = T\S = F) P{S = F)

=(l-*)p+(l-?){l-p)

If a story is published, and S ? T, it receives a payoff v, if S = F, it receives a payoff

-(d+Di). If a story is killed, its payoff is 0 regardless of S. Also, if a story is

investigated, the newspaper incurs an investigation cost, C, independent of the

signal. Thus, the expected value from publishing on a true signal (and killing on a

false signal) yields (3). Figure 2 shows the expected value of these actions. The

probability of receiving a false signal and corresponding expected value are

P(I = F) = ap + 0(1-/0

E(False) = ocpv + ?(l -p)(d + DI)

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \?s

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law *7r\

91

Thus, the expected value of publishing regardless of signal is E(False) + E{True), or

equation (2) ? C. Since (2) is the expected value from publishing without

investigation, it is inefficient under strict liability to investigate and publish

regardless of signal.

Proof of Proposition 1 Under strict liability, a newspaper can choose one of three

distinct actions: kill the story without investigation,^, investigate and publish if the

investigation signals that the story is true, (j>2, and publish without an investigation,

04. We first solve for the probability boundaries separating these actions. Then, to

determine optimal actions of the newspaper, compare the expected values for each

action relative to the regions defined (in the p?C plane) by the boundaries. E

denotes expected value.

Setting (3) equal to 0 and solving for p yields the lower probability bound:

(AD ?(d + D,) + C

K ' Ps (l-a)v + ?(d + Di)

Thus, forp>pj, E{4>2)>E{fa); forp<pj, E{<i>x)>E{<i>2).

Equating (2) and (3) yields the upper probability bound:

(M\ ? (1-/Q(rf+ />/)-C

{ ' Ps av+(l-?)(d + D,)

Likewise, for p >Ps", ?(<?4) > E(<p2); for p >ps", E(<t>2) > ?(<?4).

Since pj and p" intersect, solving pj = p" for C defines an upper bound on C,

beyond which investigation (action <j>2) no longer occurs:

(A3) ^J^L(1-?-?v

Finally, equating (2) to zero determines the boundary governing the actions of the

newspaper for OC/:

d + Di

(A4) pc>c? =v + (J + D/)

Comparing the above inequalities yields for p<pj, (?2 for pj <p<p"\ and </>4 for

p>Pswhen C<C". For C^C/, (j>i for p<Pc>c"s and </>4 for p>Pc>c"s are

obtained. The optimal actions for the newspaper are described in Figure 3.

Proof of Proposition 2 Under negligence, a newspaper can choose from actions

0i?</>2>04? and the additional action unique to negligence: investigate and publish

regardless of the signal, 03. In an approach similar to that used for Proposition 1, we

first solve for the probability boundaries, and then identify the optimal actions of

the newspaper for the regions defined by the probability bounds.

Setting (6) equal to 0 yields the lower probability bound:

(L<\ /_ ?d + C

(A5j P?-(l-a)v + ?d

For/>>/>?', E(4>$> E{4>x)\ for p<pn'9 E{4>x)> E{4>2).

Equating (6) and (2) yields the bound separating </>2 a

(A6) P" = av+{l-?)d + Dl

For p >Pn", E(4>4) > E{4>2); for p<pH", E(4>2) > E{<j)A).

Eastern Economic Journal 200

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

\i/ Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

VjV An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

92

Equating (6) and (7) yields the bound separating <j>2 and 03:

(M\ n?> {\-?){d + D,)

(A7) Pn-lt-av+(l_?){d + Di)

For/?/>?_?'", E(fc)>E{4>2); forp<pn'", E(<j>2)>E(</>3).

Equating (6) and (2) yields the bound separating $3 and </>4:

(A8) p"=~JdT

For p>Pn'", E(^)>E{h)\ for p<pn"', ?(</>3)>E(<j>4).

Since/??_?"' and/??"' intersect, solvingp?-ib" = p?'" for C defines

on C, beyond which action <j)3 no longer occurs:

(A9) C = av{?Dl)

1 } OLV+(\-?)(d + Dj)

For C<C, Pn" >Pn >Pn-ib'\ where /?/ intersects with pn_lb"

Comparing the inequalities corresponding to (A6), (A7), and (A8),

dominant action when pe (/??_//', pnfff).

For C>C, we have Pn" <Pn" <Pn-ib" Comparing the same ineq

that the actions of the newspaper are completely described by

Likewise, solving p? = pn" for C defines a second upper bound, be

optimal action is $1 for p<pc^c% or $4 for p>Pc^c"?

^-?-^+(1-^,1

v } n v + id + Dr)

Since Cn,f?C >0 , C?" > C. Likewise, since solvingpn-ib" = pn" also yields C, this is

where the boundaries intersect. The newspaper's actions are characterized by

Figure 4.

Proof of Proposition 3 By Propositions 1 and 2, pj </?/, Pn<pn", and, for C<C,

Pn <Pn-ib"<Pn"> Thus, to show that the combined inequalities hold, we establish

the following bilateral relationships:

(a) C/>C/. Proof: C/'-C/X).

(b) pj and ps" intersect to the left of pnf and pn". Proof: Cn" > C/.Let C<C?", for

(b), (c), and (d):

(c) p?">Ps". Proof: Pn"-Ps">0.

(d) pj>pnf. Proof: Since (l-a)v-C/>0, (l-a)v>C. Therefore, psf-pn'>0.

(e) Pn-ib" >Ps\ when (K C< C. Proof: />?_//'-/>/>0.

Proof of Proposition 4 Substituting F for v and D for d into (Al) and (A2) yield the

following optimal boundaries for society:

(All) / ?^ + (1Dl) + C

- a)V + ?(Ds + Dj)

(I - ?)(Ds + D,) - C

(A12)

' ?V + {I - ?)(Ds + DT)

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo \I/

An Economic Analysis of Libel Law TtV

93

DERIVATION OF EQUATION (9)

When C<Cthe expected welfare equation is composed of three terms: the first is

the expected welfare from action 02, the second is the expected welfare from 03, and

the third is the expected welfare from </>4:

Pn-lb

(A13) WN,c<c> = P'nf \p(l-a)V-(l-p)?(Ds + nI)-C}f(p)dp

P'n

+ Pn-lb

j p(l-a)V-(l-p)?(Ds + Dj)

+ paV - (1 -p)(l - ?)(Ds + Dj) - Cf(p)dp

l

+ Pnj IpV-il-p^Ds + DjW^dp

Because society internalizes all costs regardless of liability standard, the objective

function of the second term is that of the first term less the cost of investigation. The

equation simplifies to (9).

Proof of Proposition 5a Under strict liability, the newspaper chooses pj and p" to

subject to the subsidy Ss and attenuation of damages y. Define Z= C-Ss, the net

cost of the investigation after receiving the subsidy. Equations (Al) and (A2)

become

(ah) ,; = . M+ + *

(1 -^v + ?id + yDj)

,A1sx (l-?^d + yD^-X

[ ' Ps av + (l-?)(d + yDr)

Let: Ss = (l-v/V)C and y = [v/V(Ds +Di)-d\l/Dj.

Substituting Ss and y into (A 13) and (A 14) yields the socially optimal

(All) and (A12).

Proof of Proposition 5b Define X= C-SN. Under negligence the newspaper

the lower critical probability p?' subject to X; thus, (A5) becomes

fAItt ?' ?d + X

(A16) '^(l-oOv + ZW

Equating (A 15) to (A 10) and solving for SN yields the socially optimal subsidy

<a,7> 5?'(1-l')^);(+z,r+P,)^+j-'+ci-^

This reduces to

(a18) SN = (l-ayB[-dV + v(Ds + Di)] + C

(l-a)V + ?(Ds + Di)

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manoj Dalvi and James F. Refalo

VfV An Economic Analysis of Libel Law

94

To derive the corresponding socially optimal damage scaling, note that (A6) likewise

becomes

(A19) {\-?)d + yNDI-X

{ ' Pn av+(l-?)d + yNDr

Equating to (All), and solving for yN,

_ [qv + (1 - ?)d] [(1 - ?)(Ds + D,) - C] - [X + (1 - ?)d] [aV + (1 - ?)(Ds + D,)]

(A20) JN ~ {\-*)V + ?{Ds + D,)

Therefore, SN and yN are sensitive to the values of a and ?.

Note: Even under the assumption v/V=d/Ds = K,

(A21) SN = {l-K)C-K {l~a)?DlV

[(1 - a) V + ?(Ds + Df)]

Eastern Economic Journal 2008 34

This content downloaded from

49.205.135.190 on Sat, 28 Oct 2023 11:39:03 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Code Name Helene: Inspired by The Gripping True Story of World War 2 Spy Nancy Wake - Ariel LawhonDocument5 pagesCode Name Helene: Inspired by The Gripping True Story of World War 2 Spy Nancy Wake - Ariel Lawhonmycodema67% (3)

- Angel Maravilla-Garcia - 4 Progressive Presidents Graphic OrganizerDocument2 pagesAngel Maravilla-Garcia - 4 Progressive Presidents Graphic Organizerapi-471533710No ratings yet

- 6001H Service Manual Tier III DUMPERDocument300 pages6001H Service Manual Tier III DUMPERAlberto100% (3)

- Roy Safety First 1952Document20 pagesRoy Safety First 1952OVVOFinancialSystems100% (2)

- Ensuring Corporate Misconduct: How Liability Insurance Undermines Shareholder LitigationFrom EverandEnsuring Corporate Misconduct: How Liability Insurance Undermines Shareholder LitigationNo ratings yet

- Liability For Harm Aversus Regulation of SafetyDocument19 pagesLiability For Harm Aversus Regulation of SafetySiddiqiNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 212.128.135.58 On Thu, 05 May 2022 08:18:03 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 212.128.135.58 On Thu, 05 May 2022 08:18:03 UTCLeandro BicalhoNo ratings yet

- Using Repayment Data To Test Across Models of Joint Liability LendingDocument41 pagesUsing Repayment Data To Test Across Models of Joint Liability LendingrollinpeguyNo ratings yet

- CSI: A Hybrid Deep Model For Fake News DetectionDocument11 pagesCSI: A Hybrid Deep Model For Fake News Detectionsony stew rios cahuasNo ratings yet

- A Hybrid Bankruptcy Prediction Model With Dynamic Loadings On Acct-Ratio-Based and Market-Based InfoDocument16 pagesA Hybrid Bankruptcy Prediction Model With Dynamic Loadings On Acct-Ratio-Based and Market-Based InfoTitoHeidyYantoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00Document74 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00skywardsword43No ratings yet

- Richardson 1959Document16 pagesRichardson 1959Guilherme MachadoNo ratings yet

- Karteli Korporativno Uskladenost I Što Praktičari Zaista Misle o IzvršenjuDocument40 pagesKarteli Korporativno Uskladenost I Što Praktičari Zaista Misle o IzvršenjuKanita Imamovic-CizmicNo ratings yet

- Variation in Systemic Risk at US Banks During 1974-2010: Armen Hovakimian Edward Kane Luc LaevenDocument47 pagesVariation in Systemic Risk at US Banks During 1974-2010: Armen Hovakimian Edward Kane Luc Laevenrichardck61No ratings yet

- Untitled 2Document4 pagesUntitled 2Luddu MinhNo ratings yet

- Diamond - Financial Intermediation and Delegated MonitoringDocument24 pagesDiamond - Financial Intermediation and Delegated MonitoringMario1199No ratings yet

- FinalExamSpring2012 WithanswerkeyDocument14 pagesFinalExamSpring2012 WithanswerkeyJohnNo ratings yet

- Riordan TaxonomyDocument38 pagesRiordan TaxonomyLala DarchinovaNo ratings yet

- Size and Performance of Banking Afirms - Testing The Predictions of TheoryDocument21 pagesSize and Performance of Banking Afirms - Testing The Predictions of TheoryAlex KurniawanNo ratings yet

- The Economics of PenaltiesDocument13 pagesThe Economics of PenaltiesCore ResearchNo ratings yet

- 26 Financial Intermediate TheoryDocument23 pages26 Financial Intermediate TheoryAgung Putu MirahNo ratings yet

- Shavell Strict Liability V Negligence PDFDocument35 pagesShavell Strict Liability V Negligence PDFPiera CastroNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Weils The Fissured Workplace-Parte 3Document237 pages2014 - Weils The Fissured Workplace-Parte 3André DorsterNo ratings yet

- Discrimination in The Age of AlgorithmsDocument62 pagesDiscrimination in The Age of AlgorithmsLegaleLegalNo ratings yet

- Speech To The 2013 Law Institute of Victoria Legal SymposiumDocument6 pagesSpeech To The 2013 Law Institute of Victoria Legal SymposiumLR HowardNo ratings yet

- Boyd, J. H., & Runkle, D. E. (1993) .Document21 pagesBoyd, J. H., & Runkle, D. E. (1993) .Vita NataliaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 65.0.53.109 On Tue, 01 Dec 2020 17:13:02 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 65.0.53.109 On Tue, 01 Dec 2020 17:13:02 UTCSiddhant makhlogaNo ratings yet

- Credit Rationing in Developing Countries:: An Overview of The TheoryDocument24 pagesCredit Rationing in Developing Countries:: An Overview of The TheorymitalptNo ratings yet

- Discrimination in The Age of AlgorithmsDocument62 pagesDiscrimination in The Age of AlgorithmsArnaldoNo ratings yet

- The Review of Economic Studies, LTDDocument19 pagesThe Review of Economic Studies, LTDnaoto_somaNo ratings yet

- Legitimacy Theory Australian Food - Beverage IndustryDocument35 pagesLegitimacy Theory Australian Food - Beverage IndustryusertronNo ratings yet

- R L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONEDocument28 pagesR L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONE3rlangNo ratings yet

- Gutirrez EconomicAnalysisCorporate 2003Document21 pagesGutirrez EconomicAnalysisCorporate 2003pluxury baeNo ratings yet

- The Econometric Society Econometrica: This Content Downloaded From 148.210.71.189 On Mon, 08 Apr 2019 23:28:37 UTCDocument21 pagesThe Econometric Society Econometrica: This Content Downloaded From 148.210.71.189 On Mon, 08 Apr 2019 23:28:37 UTCAdyCastilloNo ratings yet

- Amdur CompensatoryJusticeQuestion 1979Document17 pagesAmdur CompensatoryJusticeQuestion 1979Tanay BansalNo ratings yet

- A Theory of NegligenceDocument69 pagesA Theory of Negligenceasclepius1013613No ratings yet

- Big Data and DiscriminationDocument29 pagesBig Data and Discriminationsmtorres2008No ratings yet

- Peru Shantytown Measure TrustDocument18 pagesPeru Shantytown Measure TrustFanny Sylvia C.No ratings yet

- 2.4. Summary: Newspaper Viewership Reaches Record in 2007 - Newspaper Association of AmericaDocument5 pages2.4. Summary: Newspaper Viewership Reaches Record in 2007 - Newspaper Association of AmericaGiorgio CivitareseNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument64 pagesCorruptionHamna AnisNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document11 pagesAssignment 3Denny ChakauyaNo ratings yet

- Agency Problems, Screening and Increasing Credit LinesDocument41 pagesAgency Problems, Screening and Increasing Credit LinesBen ShionNo ratings yet

- Psychologist, 39Document4 pagesPsychologist, 39kevinNo ratings yet

- Journal of Economic Issues Volume 33 Issue 1 1999 (Doi 10.2307/4227412) James Forder - Central Bank Independence - Reassessing The MeasurementsDocument19 pagesJournal of Economic Issues Volume 33 Issue 1 1999 (Doi 10.2307/4227412) James Forder - Central Bank Independence - Reassessing The MeasurementsEugenio MartinezNo ratings yet

- Business Fin Account - 2009 - Han - The Role of Collateral in Entrepreneurial FinanceDocument32 pagesBusiness Fin Account - 2009 - Han - The Role of Collateral in Entrepreneurial Financezilin LiNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory Review and EvidenceDocument6 pagesAgency Theory Review and EvidenceIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Industrial Organization VOLUME 23 ISSUE 9-10 PAGES 829-848Document20 pagesInternational Journal of Industrial Organization VOLUME 23 ISSUE 9-10 PAGES 829-848oliviaionelaNo ratings yet

- Early UnmaskingBlackKnights 2011Document23 pagesEarly UnmaskingBlackKnights 2011Alina SokolenkoNo ratings yet

- Banfield - 1975 - Corruption As A Feature of Governmental OrganizationDocument20 pagesBanfield - 1975 - Corruption As A Feature of Governmental OrganizationMiftahul khairNo ratings yet

- Toward Unlimited Shareholder Liability For Corporate Torts - Hansmann - KraakmanDocument57 pagesToward Unlimited Shareholder Liability For Corporate Torts - Hansmann - KraakmanTHIAGO LOBO GOMES DE SOUZANo ratings yet

- Stanford Institute For Economic Policy Research: Consumer Bankruptcy: A Fresh StartDocument36 pagesStanford Institute For Economic Policy Research: Consumer Bankruptcy: A Fresh StartHerta PramantaNo ratings yet

- Problem As Público S 2Document29 pagesProblem As Público S 2BRUNNA FELKL DO NASCIMENTONo ratings yet

- The Journal of Finance - 2023 - GRAHAM - Employee Costs of Corporate BankruptcyDocument51 pagesThe Journal of Finance - 2023 - GRAHAM - Employee Costs of Corporate Bankruptcyakuntansyaf10No ratings yet

- Demonstrating NGO PerformanceDocument9 pagesDemonstrating NGO PerformancelenaNo ratings yet

- Optimal Automatic StabilizersDocument67 pagesOptimal Automatic StabilizersNarcis PostelnicuNo ratings yet

- Pension Forfeiture and Police MisconductDocument34 pagesPension Forfeiture and Police MisconductABC6/FOX28No ratings yet

- Optimal Release of Information Firms: Douglas W. DlamondDocument24 pagesOptimal Release of Information Firms: Douglas W. DlamondLip SyncersNo ratings yet

- Wiley Journal of Accounting Research: This Content Downloaded From 171.79.1.63 On Sat, 28 Mar 2020 02:21:52 UTCDocument24 pagesWiley Journal of Accounting Research: This Content Downloaded From 171.79.1.63 On Sat, 28 Mar 2020 02:21:52 UTCGunjan YadavNo ratings yet

- BesleyDocument18 pagesBesleyrollinpeguyNo ratings yet

- CALABRESI, Guido, Some Thoughts On Risk Distribution and The Law of TortsDocument56 pagesCALABRESI, Guido, Some Thoughts On Risk Distribution and The Law of TortsGabriel CostaNo ratings yet

- A Theory of NegligenceDocument69 pagesA Theory of NegligenceNikita KolesnikovNo ratings yet

- Credit Derivatives Handbook: Global Perspectives, Innovations, and Market DriversFrom EverandCredit Derivatives Handbook: Global Perspectives, Innovations, and Market DriversNo ratings yet

- The VaR Modeling Handbook: Practical Applications in Alternative Investing, Banking, Insurance, and Portfolio ManagementFrom EverandThe VaR Modeling Handbook: Practical Applications in Alternative Investing, Banking, Insurance, and Portfolio ManagementNo ratings yet

- Waterlogging and SalinityDocument34 pagesWaterlogging and SalinityEmaan ShahNo ratings yet

- 152 Ang Higa Vs PeopleDocument2 pages152 Ang Higa Vs PeopleAngelo NavarroNo ratings yet

- DECREE No.128-2021-ND-CPDocument13 pagesDECREE No.128-2021-ND-CPDat NguyenNo ratings yet

- Quiz Unit 1 (Calificable) - Revisión Del IntentoDocument5 pagesQuiz Unit 1 (Calificable) - Revisión Del IntentoFerney Fernandez CorteceroNo ratings yet

- Boi Data - FDocument2 pagesBoi Data - FSharif Al Hasan MonshiNo ratings yet

- Instruction ManualDocument9 pagesInstruction ManualUmmu HalimahNo ratings yet

- GNSS RTK BrochureDocument2 pagesGNSS RTK BrochureHugo LabastidaNo ratings yet

- Kongsberg Oil and Gas Technology LimitedDocument1 pageKongsberg Oil and Gas Technology LimitedGhoozyNo ratings yet

- Food Network Magazine - March 2014 (Food Network) (Z-Library)Document163 pagesFood Network Magazine - March 2014 (Food Network) (Z-Library)Stephanie ANo ratings yet

- Cook Islands MoA Business Plan 2014-15Document38 pagesCook Islands MoA Business Plan 2014-15Sami GulemaNo ratings yet

- Unit 7Document43 pagesUnit 7刘宝英No ratings yet

- 17 Pacific Commercial Co V YatcoDocument2 pages17 Pacific Commercial Co V YatcoVic RabayaNo ratings yet

- Cambra: A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide For Dental ProfessionalsDocument49 pagesCambra: A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide For Dental ProfessionalsIsla Yadira Avendaño ToledoNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Local Exteri or Wind Pressures From Wind Tunnel Studies Using at Ime HistoryDocument10 pagesPrediction of Local Exteri or Wind Pressures From Wind Tunnel Studies Using at Ime Historysilvereyes18No ratings yet

- Nike - Case StudyDocument25 pagesNike - Case StudyDaniyal AghaNo ratings yet

- RFP 18-017, Bidding DocumentsDocument52 pagesRFP 18-017, Bidding DocumentsSid Ali Oulad SmaneNo ratings yet

- NEBOSH Certificate Courses IntroDocument25 pagesNEBOSH Certificate Courses IntroravikpandeyNo ratings yet

- Talkabout T400 Series User GuideDocument2 pagesTalkabout T400 Series User GuideFederico Caso A.No ratings yet

- MapbasicDocument886 pagesMapbasichcagasNo ratings yet

- Communiques DP DP 240 Facility For BSDADocument2 pagesCommuniques DP DP 240 Facility For BSDASujithShivuNo ratings yet

- MSC Economics Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesMSC Economics Thesis Topicsstephaniemoorelittlerock100% (2)

- MAPEH10 FourthDocument4 pagesMAPEH10 FourthJoahnna Grace SalinasalNo ratings yet

- Clock Gen CPU: Thermal ControlDocument57 pagesClock Gen CPU: Thermal ControlGeany Oliva RodriquezNo ratings yet

- Positive, Zero, Negative Sequence of AlternatorDocument3 pagesPositive, Zero, Negative Sequence of AlternatorJeya Kannan100% (1)