Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Rheumatic Fever: Ditorial

Acute Rheumatic Fever: Ditorial

Uploaded by

Reni Gaby TampubolonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Acute Rheumatic Fever: Ditorial

Acute Rheumatic Fever: Ditorial

Uploaded by

Reni Gaby TampubolonCopyright:

Available Formats

EDITORIAL

Acute rheumatic fever

Carceller A

Pediatrics Department. CHU Sainte-Justine. Université de Montréal. Montreal. Canada.

Unreliable legend related that Vi- tations known in the 17th Century as ˝Rheumatism˝ and

tus’ intercession freed Emperor

Diocletian’s son of an evil spirit

it was described first by Guillaume Du Baillou in France

and cured from so called “Saint (1538) and by Thomas Sydenham in England (1686)3.

Vitus Dance”. Probably if Vitus Sydenham used the designation St. Vitus’ dance to de-

was born in our era, he has never

been saint, because we know

scribe chorea4. In 1761 Morgagni (in Italy) described the

now, chorea is able to resolve valvular lesions. Joseph-Irénée Itard, a Parisian medical

without treatment and without a student probably was in 1824, the first to study this dis-

miracle. Saint Vitus (died 303) is

the patron of children and in-

ease; he sustained a twenty-four-page thesis for gradua-

voked against Saint Vitus Dance or tion from medical school entitled “Considerations sur le

Sydenham’s Chorea. Rhumatisme de Coeur”5. Richard Bright in 1838, a promi-

nent London physician called attention in his Lecture at

A CASE the College of Physicians in London, to the association

1838. Ten-year-old girl complained of general rheumat- of chorea with diseases of pericardium and he was the

ic symptoms; pains in the limbs, with puffiness and first to associate all the anomalies with rheumatic fever2.

swelling of the wrists, and some other joints. Six days lat- Dr James Kingston Fowler, who was serving as house

er, she developed chorea: her head was constantly tilting physician at King’s College Hospital in 1874, contracted

from one side of the bed to the other; her lips closed and a rheumatic fever and he was the first to report tonsillitis

opened with a smacking sound, and when she tried to as a common precursor of rheumatic fever in collabora-

put out her tongue it protruded in a forced grimace. tion with Walter Butler Cheadle6. It is in 1904 that Aschoff

A rapid and irregular heart-beat led to suspect that the described the cardiac nodules. In 1928 in New York, F

heart was also affected. Sixteen days later, the girl died. Swift introduced the hypothesis that rheumatic fever re-

After the autopsy, Bright1 discovered that both the peri- sults from the development of hypersensitivity to Strepto-

cardium and the endocardium were involved. Careful dis- cocci and is only in 1932 that Edgar W Todd evidenced to

section of the brain failed to yield any perceptible abnor- support the hypothesis of an immune pathogenesis of

malities2. rheumatic fever with the discovery of antistreptolysins4.

In 1944, T Duckett Jones gave the first lecture about RF.

DEFINITION

Rheumatic Fever (RF) is a delayed and inflammatory EPIDEMIOLOGY

disease non suppurative sequel of upper respiratory in- The frequency of the RF was 100-200 cases per 100,000

fection with group A Streptococci. in the US population in 1900 and 50 per 100,000 in 1940.

Until the early 1980’s there was a decline to about 0.5 per

HISTORY 100,000 with a localized outbreaks7-14. In Europe, there

Acute migratory arthritis of children appeared in the have been similar declines and it has become a rare dis-

time of Hippocrates, a physician born in 460 BC on the is- ease. Although, in undeveloping countries, RF still en-

land of Cos, Greece. The term chorea derived from a demic and remains the major cause of acquired heart dis-

Greek word “khoreia” which means “dancing”. It was in- ease in young adults.

troduced by Paracelsus (1493-1541) to describe hysterical Factors relating to the decrease in RF were still un-

movements of religious fanatics during the Middle Age. known15. Over the past Century, living conditions and

The concept of Rheumatic Fever evolved from manifes- crowding were improved in most countries, contributing

Correspondence: Ana Carceller MD.

Department of Pediatrics. CHU Sainte-Justine.

3175 Côte Ste-Catherine. Montréal. Québec H3T 1C5. Canada.

E-mail: ana_carceller@ssss.gouv.qc.ca

An Pediatr (Barc). 2007;67(1):1-4 1

Carceller A. Acute rheumatic fever

to the declining of the disease. We don’t know if viru- exhibiting specific HLA antigen; all these factors suggest

lence of group A Streptococci is declining or if human re- that RF may be modulated by the specific genetic consti-

sistance to these bacteria is increasing. Of course, peni- tution of the host23.

cillin treatment has contributed to declining mortality and

morbidity due to streptococcal infections, including RF, CLINICAL EXPRESSION

but the reasons for the decline before penicillin were not The diagnosis of RF is based on clinical criteria and

apparent16. The incidence and prevalence of this disease may be difficult to establish it given the current rarity of

steadily have declined as has mortality in the past the disease and the absence of any pathognomonic labo-

decade17-19. Factors that have contributed to the decrease ratory tests.

in the incidence of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) may The migratory polyarthritis with fever was the initial

include changes in the host, the environment or the sign of RF in the past in approximately 75 % of patients,

pathogen17. actually is really less frequently seen. Knees, ankles, el-

RF usually appears between 5 and 18 years old patients bows and wrists are the most commonly affected joints;

and it is rare before the age of 3 years. arthritis improves without treatment in 1 to 3 days and it

has a dramatic response to salicylates25. Recent interna-

PATHOGENESIS tional studies documented monoarticular arthritis as a

Despite epidemiological and clinical research, the pre- presenting sign in ARF26. Although in 2000, the Jones Cri-

cise pathogenesis of RF remains unknown20. Socio-eco- teria Working Group27 acknowledged the importance of

nomic factors have little importance in RF occurrence. monoarticular arthritis among people in undeveloped

Some authors currently favour the theory that ARF is an countries, this diagnosis has not been universally accept-

autoimmune disorder after an immunologic cross-reaction ed as major criteria in developed countries. The Work-

response to the antecedent streptococcal infection21. shop27 did not address the potential need for antibiotic

Group A Streptococci vary in their rheumatogenic po- prophylaxis in patients with post streptococcal reactive

tential. Strains causing clusters or epidemics usually be- arthritis who did not fulfill the Jones Criteria.

long to certain serotypes 1, 3, 5, 6, 18, 19, 24 and are of- Carditis, the most serious manifestation of RF occurs

ten heavily encapsulated as evidenced by their growth as within 3 weeks after Group A streptococcal infection. It is

mucoid colonies on blood agar plates. Approximately 3 % a pancarditis: Endocarditis that is almost always present,

of untreated patients could to develop ARF21. mitral regurgitation is the most common pathology in RF

Rheumatogenic Streptococci adhere to pharyngeal associated or not to the aortic regurgitation; Myocardial

cells22. The absorbed products of streptococcal degrada- disease with atrioventricular conduction disorders or with

tion act as antigens and have molecular mimicry with congestive heart failure and Pericarditis who is rare

different human tissues. They are identified by the (< 5 %). Cardiac involvement is seen in about 50 % of pa-

macrophages and presented to the T cell receptors pro- tients with ARF and with the help of echocardiography

ducing cytokines which activates B cells to become im- in about 70 %. The use of Doppler-echocardiography

munoglobulin. Antibodies to the Streptococci may should be used as an adjunctive technique to confirm

cross-react with heart, brain and/or joint tissue resulting clinical auscultatory findings; although, it should not be

in carditis, chorea or arthritis. Components of the strep- used as a major or minor criterion for establishing the di-

tococcal cell wall and of the cell membrane contain epi- agnosis of carditis associated with ARF27. Clinical research

topes that share antigenic determinants with certain con- is needed to determine the prognostic implications of

stituents of the human tissues. The hyaluronic acid and subclinical valvular regurgitation.

the N-Acetyl glucosamine in capsule react with the Sydenham’s Chorea is a delayed manifestation of RF

hyaluronic acid of joint tissue. M-Protein, the group A car- (occurs 1 to 6 months) after a Group A streptococcal in-

bohydrate and the N-Acetyl glucosamine in cell wall react fection. Resulting from an autoimmune attack on the CNS,

with tropomyosine, myosine and glycoprotein of the sera from patients with chorea contain antibodies that

heart. Lipoproteins in Protoplasm react with neuronal tis- cross-react with basal ganglia neurons. Pathophysiology

sue and affect basal ganglia regions of the caudate and of Sydenham Chorea can be divided into four areas: Neu-

putamen. This humoral reaction clears without sequel. roanatomy with basal ganglia regions of the caudate,

Persistent rheumatic heart disease, as Aschoff body, is a putamen and subthalamic nucleus dysfunction; Neuro-

result of cellular reaction and is the persistence of T cell chemistry with imbalance among the dopaminergic,

activity in valve tissue23,24. cholinergic and the inhibitory gamma aminobutyric acid

Although, several observations show that more than systems; Immunology with production of antineuronal

one member is affected in the same family, only small antibodies and inflammatory cytokines and Genetics as RF

percentage of individuals experienced streptococcal in- frequently appeared in multiple members of a family28.

fection, some individuals developing recurrent attacks or This disorder is characterized by sudden non-voluntary

2 An Pediatr (Barc). 2007;67(1):1-4

Carceller A. Acute rheumatic fever

arrhythmic and clonic purposeless mouvements. Some- without raised antibody levels30. The ESR or CRP should

times, children present hypotonia, gait disturbance, inco- be measured and usually they are increased. Chorea

ordination, loss of fine motor control, facial grimacing, could be present as isolated manifestation, frequently

gross fasciculations of the tongue, and speech abnormal- when a patient presents, acute phase reactant levels may

ities with dysarthria, explosive speech and emotional la- have normalized.

bilities. Chorea is a clinic diagnostic due to the lower fre-

quency of others positive results of the laboratory and OUTCOME

may present without any other major or minor features of Deaths are related to heart failure and it is really rare

RF. She was frequently seen in the 1950’s and her inci- in industrialized countries. Prophylaxis prevents recur-

dence declined substantially to 10-30 %. Neuro-imaging as rences. Relapses are more frequent in the first 3 years af-

increased signal in the caudate and putamen nucleus ter a first episode of RF. Patients with residual valve dis-

have been reported in patients with Sydenham’s chorea. ease must be followed by echocardiography every

Chorea resolves in 2 to 3 months, the treatment of Syden- 6 months for the first 2 years after first episode of RF.

ham’s Chorea is purely symptomatic and different drugs

are used in her treatment although a few studies strongly TREATMENT

support their efficacy. Susan Swedo29 was the first to de- The therapeutic management of the ARF need to treat

scribe the paediatric auto-immune neuropsychiatric disor- the inflammatory process, to eradicate the Streptococcus

ders associated with Streptococcus (PANDAS) as different and to continue for long term prophylaxis.

diagnosis from Syndenham’s chorea. An anti-inflammatory treatment are required if severe

Transient erythema marginatum occurs to less than 2 % carditis is present: prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day and less

of patients; it consists of erythematous serpiginous, mac- than 80 mg/day, given in 1 dose/day for 3-4 weeks de-

ular lesions with pale central clearing on the trunk and creasing over 6-8 weeks and followed by aspirin who is

extremities. Subcutaneous nodules occur in less than 1 % started 1 week before termination of steroids. The dose of

of cases and they resolve within one month without aspirin is 80-100 mg/kg/day, 4 doses/day during

long-term sequelae. They are firm, non-tender, varying 4-8 weeks; decreasing over the following 4 weeks. In

in size from a few millimetres to 1-2 cm of diameter, over mild to moderate carditis, corticosteroids are not essen-

bony prominences and in tendon sheaths30. tial and we can treat with aspirin directly.

Patients need to receive penicillin for ten days to erad-

CRITERIA icate Streptococcus.

Criteria are used at the acute stage of the disease. The The prophylaxis consisted to receive intramuscular

first criteria were established by Jones31 in 1940 and there penicillin benzathine given every 28 days, if bodyweight

were some updates, the last one in 199225,32-34. In 2000, is less than 27 kg the dose is 600,000 international units

the American Heart Association agreed that there were in- (IU), if bodyweight is more than 27 kg, the dose is

sufficient data to support a revision of the Jones Criteria 1.200,000 IU. In the cases where intramuscular penicillin

and reaffirmed the guidelines iterated in the 1992 state- is not safe, we can give 250 mg twice per os of Penicillin

ment27. V and in the case of allergy to penicillin we can use ery-

The diagnosis of RF is highly suggested when two ma- thromycin 250 mg twice per os.

jor criteria or one major and two minor criteria are ful- All children who have suffered cardiac sequelae must

filled in a patient with previous streptococcal infection di- be thoroughly instructed on risk prevention of bacterial

agnosed by positive culture of throat and/or elevated or endocarditis (AMH)37.

rising streptococcal antibody titter. In conclusion:

Major criteria are polyarthritis, carditis, chorea, erythe- 1. Although the acute rheumatic fever has become a

ma marginatum and subcutaneous nodules. Minor criteria rare disease in industrialized countries, it remains preva-

are fever, arthralgia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation lent.

rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) and prolonged PR 2. In 2000, the American Heart Association agreed that

interval on the electrocardiogram. there were insufficient data to support a revision of the

RF is now a rare disease in most of Europe and North Jones Criteria and reaffirmed the guidelines iterated in the

America, making its diagnosis more difficult to establish. 1992 statement.

3. In pediatrics, Criteria are a guide but should not re-

DIAGNOSIS place clinical judgment.

Positive throat culture of Group A Streptococcal infec-

tion is infrequently found and the absence of a positive

culture does not exclude the diagnosis of RF35,36. Anti- Acknowledge

streptolysin O antibody (ASO) and anti-DNase B are of The author would like to thank Mrs Ana Maria C. Blan-

limited diagnostic value because 20 % of cases presented chard for her English expertise.

An Pediatr (Barc). 2007;67(1):1-4 3

Carceller A. Acute rheumatic fever

REFERENCES 18. Markowitz M. Rheumatic Fever in the Eighties. Ped Clin of

North Am. 1986;33:1141-50.

1. Richard Bright. Cases of spasmodic disease accompanying af- 19. Rammelkamp CH, Wannamaker LW, Denny FW. The epidemi-

fections of the pericardium. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. ology and prevention of Rheumatic Fever. Bull of the NY Ac of

1839;22:1-19. Med. 1997;74:119-36.

2. English PC. Rheumatic fever in America and Britain. A biolog- 20. Kaplan EL, Bisno AL. Antecedent streptococcal infection in

ical, epidemiological and medical history. New Jersey: Rut- acute rheumatic fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:690-2.

gers University Press; 1999. p. 17-52.

21. Ayoub EM, Ahmed S. Update on complications of Group A

3. Denny FW. A 45-year perspective on the Streptococcus and Streptococcal Infections. Problems in Pediatrics. 1997;27:90-9.

rheumatic fever. In: Edward H, editor. Kass Lecture in Infec-

tious Disease History. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1110-22. 22. Williams RC Jr. Host factors in rheumatic fever and heart dis-

ease. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1982;17:125-9, 135-8.

4. Schumacher HR, Klippel JH, Koopman WJ. Primer on the

rheumatic diseases. Published by the Arthritis Foundation. 10th 23. Veasy LG, Hill HR. Immunologic and clinical correlations in

ed. Atlanta, Georgia; 1993. p. 1-2. rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Pediatr Infect Dis

J. 1997;16:400-7.

5. Joseph-Irénée Itard. Considérations sur le rhumatisme du

Coeur, thèse présentée et soutenue à la Faculté de Médecine 24. Bisno AL. Group A streptococcal infections and acute

de Paris, le 13 juillet 1824, pour obtenir le grade de docteur en rheumatic fever. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:783-93.

médicine.

25. Dajani AS, Ayoub E, Bierman FZ, Bizno AL, Denny FW, Du-

6. Sir James K. Fowler. On the association of the throat with rack DJ. Guideliness for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever.

Acute Rheumatism. Lancet. 1880;116:933-4. Jones Criteria, 1992 update. Special Writing Group of the Com-

7. Hosier DM, Craenen J, Teske DW, Wheller JJ. Resurgence of mittee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Dis-

Rheumatic Fever. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:730-3. ease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young

of the American Heart Association. JAMA. 1992;268:2069-73.

8. Congeni B, Rizzo C, Congeni J, Sreenivasan VV. Outbreak of

acute rheumatic fever in Northeast Ohio. J Pediatr. 1987;111: 26. Harlan GA, Tani LY, Byington CL. Rheumatic fever presenting

176-9. as monoarticular arthritis. Ped Infect Dis J. 2006;25:743-6.

9. Wald ER, Dashefsky B, Feidt C, Chiponis D, Byers C. Acute 27. Ferrieri P. Jones Criteria working group. Proceedings of the

Rheumatic Fever in Western Pennsylvania and the Tri-State Jones Criteria Workshop. Circulation. 2002;106:2521-3.

area. Pediatrics. 1987; 80:371-4. 28. Marqués-Días MJ, Mercadante MT, Tucker D, Lombroso P.

10. Zomorrodi A, Wald ER. Sydenham’s Chorea in Western Penn- Sydenham’s Chorea. Psychiatric Clin North Am. 1997;20:809-19.

sylvania. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e675-9. 29. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perl-

11. Veasy LG, Wiedmeier SE, Orsmond GS, Ruttenberg HD, mutter S, et al. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disor-

Boucek MM, Roth SJ, et al. Resurgence of acute rheumatic ders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical descrip-

fever in the intermountain area of the United States. N Engl J tion of the first 50 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:264-71.

Med. 1987;316:421-7. 30. Guzman-Cottrill JA, Jaggi P, Shulman ST. Acute rheumatic

12. Feuer J, Spiera H. Acute rheumatic fever in adult: A resurgence fever: Clinical aspects and insights into pathogenesis and pre-

in the Hasidic Jewish Community. The J of Rheumatolog. vention. Clin and Applied Immunol Reviews. 2004;4:263-76.

1997;24:337-40. 31. Jones TD. Diagnosis of rheumatic fever. JAMA. 1944;126:481-4.

13. Gunzenhauser JD, Longfield JN, Brundage JF, Kaplan EL, 32. Shiffman RN. Guideline maintenance and revision. 50 years of

Miller RN, Brandt CA. Epidemic Streptococcal Disease among the Jones Criteria for Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever. Arch Pe-

Army Trainees, July 1989 through June 1991. J Infect Dis. 1995; diatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:727-32.

172:124-31.

33. Shulman ST. T. Duckett Jones and his Criteria for the Diagno-

14. Gordis L. The virtual disappearance of rheumatic fever in the sis of Acute Rheumatic Fever. Ped Annals. 1999;28:9-12.

United States: lessons in the rise and fall of disease. T. Duck-

ett Jones Memorial Lecture. Circulation. 1985;72:1155-62. 34. Forster J. Rheumatic fever: Keeping up with the Jones Crite-

ria. Contem Pediatr. 1993;10:51-60.

15. Quinn RW. Comprehensive Review of Morbidity and Mortality

Trends for Rheumatic Fever, Streptococcal Disease and Scarlet 35. Mirkinson L. The diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever. Ped Rev.

Fever: The decline of Rheumatic Fever. Rev Infect Dis. 1989; 1998;19:310-1.

11:928-53. 36. Alsaeid K, Majeed HA. Acute rheumatic fever: Diagnosis and

16. Stollerman GH. The return of rheumatic fever. Hosp Pract. treatment. Ped Annals. 1998;27:295-300.

1988;23:100-6, 109-13. 37. Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Bolger AF, Bayer A, Ferrieri

17. Lee GM, Wessels MR. Changing epidemiology of acute rheumat- P, et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations

ic fever in the United States. Editorial. CID. 2006;42: 448-50. by the American Heart Association. JAMA. 1997;277:1794-801.

4 An Pediatr (Barc). 2007;67(1):1-4

You might also like

- Harrison Self-Assessment and Board Review (1) - 403-490Document88 pagesHarrison Self-Assessment and Board Review (1) - 403-490Cristobal Andres Fernandez Coentrao100% (2)

- CVS1 - K7 - Rheumatic Fever & Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocument15 pagesCVS1 - K7 - Rheumatic Fever & Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDumora FatmaNo ratings yet

- Davis General Paralysis of The InsaneDocument8 pagesDavis General Paralysis of The InsaneSistemassocialesNo ratings yet

- Corynebacterium Ulcerans Cutaneous Diphtheria: Grand RoundDocument8 pagesCorynebacterium Ulcerans Cutaneous Diphtheria: Grand RoundRafa NaufalinNo ratings yet

- 24 Rheumatic FeverDocument14 pages24 Rheumatic FeverVictor PazNo ratings yet

- Diphtheria: Signs and SymptomsDocument4 pagesDiphtheria: Signs and SymptomsApril Grace CastroNo ratings yet

- PRINT Korea SydenhamDocument5 pagesPRINT Korea SydenhamKristina FergusonNo ratings yet

- Rheumatic FeverDocument13 pagesRheumatic Feverpaulkimunya100No ratings yet

- The Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever: in BriefDocument4 pagesThe Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever: in BriefkholisahnasutionNo ratings yet

- 01 Bod Immunology Artificial ImmunityDocument8 pages01 Bod Immunology Artificial Immunityrtm haiderNo ratings yet

- Reiter's Syndrome: The Classic Triad and More: EpidemiologyDocument9 pagesReiter's Syndrome: The Classic Triad and More: EpidemiologyGokul SivaNo ratings yet

- Caplan 3Document2 pagesCaplan 3GaBy_Alulema_787No ratings yet

- Native Cardiac Disease Predisposing To Infective EndocarditisDocument5 pagesNative Cardiac Disease Predisposing To Infective EndocarditisAmr SalemNo ratings yet

- Neurosifilis Berger2014Document12 pagesNeurosifilis Berger2014eva yustianaNo ratings yet

- Historical Note: Poliomyelitis (Heine-Medin Disease)Document2 pagesHistorical Note: Poliomyelitis (Heine-Medin Disease)wiwin09No ratings yet

- Aquired Heart Disease - IDocument47 pagesAquired Heart Disease - Iduoltut11No ratings yet

- Ann Rheum Dis 2002 Rudwaleit 968 74Document8 pagesAnn Rheum Dis 2002 Rudwaleit 968 74Kobayashi MaruNo ratings yet

- A Chilly FeverDocument5 pagesA Chilly FeverChangNo ratings yet

- Severe TuberculosisDocument4 pagesSevere TuberculosisAdelia GhosaliNo ratings yet

- Islam 2010Document3 pagesIslam 2010koniskoNo ratings yet

- Barnert 1975Document4 pagesBarnert 1975SfuekdndNo ratings yet

- Challenges and Opportunities in Pediatric Heart Failure and TransplantationDocument15 pagesChallenges and Opportunities in Pediatric Heart Failure and TransplantationvijuNo ratings yet

- Rheumatic Fever & RHDDocument13 pagesRheumatic Fever & RHDValerrie NgenoNo ratings yet

- Edward Jenner and The History of Smallpox and Vaccination: S R, MD, P DDocument5 pagesEdward Jenner and The History of Smallpox and Vaccination: S R, MD, P DMoisés PonceNo ratings yet

- Cutting Edge Issues in Rheumatic FeverDocument25 pagesCutting Edge Issues in Rheumatic FeverGeorgi GugicevNo ratings yet

- Faktor Resiko Kejang PDFDocument10 pagesFaktor Resiko Kejang PDFHamtaroHedwigNo ratings yet

- (Cardio B) 1 - Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease (Dr. Antolin, 2019)Document4 pages(Cardio B) 1 - Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease (Dr. Antolin, 2019)NoreenNo ratings yet

- Arf NGDocument20 pagesArf NGAnonymous ZPgIFrXNLgNo ratings yet

- Covid19 PDFDocument6 pagesCovid19 PDFJeremy Kartika SoeryonoNo ratings yet

- At the Edge of Mysteries: The Discovery of the Immune SystemFrom EverandAt the Edge of Mysteries: The Discovery of the Immune SystemNo ratings yet

- Chagas Therapy NEJM 2011Document8 pagesChagas Therapy NEJM 2011Ever LuizagaNo ratings yet

- Paper Project 2Document29 pagesPaper Project 2Diaz RahmadiNo ratings yet

- Pseudomembrane) On The Tonsils, Pharynx, And/or Nasal Cavity. A Milder Form of DiphtheriaDocument4 pagesPseudomembrane) On The Tonsils, Pharynx, And/or Nasal Cavity. A Milder Form of Diphtheriahermx-psik-4865No ratings yet

- Acute Rheumatic FeverDocument50 pagesAcute Rheumatic Feversunaryo lNo ratings yet

- Clinical Review Acute Rheumatic FeverDocument4 pagesClinical Review Acute Rheumatic FeverBenazir SalsabillahNo ratings yet

- Angina de LudwingdDocument5 pagesAngina de LudwingdAldo AguilarNo ratings yet

- History of Epidemiology: Presented By: Dr. Imrose Rashid Guide & Mentor: Dr. (Prof.) S.M. Salim KhanDocument32 pagesHistory of Epidemiology: Presented By: Dr. Imrose Rashid Guide & Mentor: Dr. (Prof.) S.M. Salim KhanBijay kumar kushwahaNo ratings yet

- Diphtheria: Signs and SymptomsDocument6 pagesDiphtheria: Signs and SymptomsIssa RomaNo ratings yet

- Diphtheria The Strangling AngelDocument4 pagesDiphtheria The Strangling AngelDatu Nur-Jhun Salik, MDNo ratings yet

- Bitar 1985Document15 pagesBitar 1985Shaznay Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Unusual Cause of Fever in A 35-Year-Old Man: ECP YuenDocument4 pagesUnusual Cause of Fever in A 35-Year-Old Man: ECP YuenhlNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of RADocument4 pagesPathogenesis of RAreemNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: SyphilisDocument49 pagesHHS Public Access: Syphilisfaty basalamahNo ratings yet

- Tifus Transmitido Por PulgasDocument9 pagesTifus Transmitido Por Pulgascaos. educativa2No ratings yet

- Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Diphtheria: BackgroundDocument19 pagesOphthalmologic Manifestations of Diphtheria: BackgroundIrenLayNo ratings yet

- Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocument39 pagesRheumatic Heart DiseaseRyo KelvinNo ratings yet

- HIV ArnettDocument24 pagesHIV ArnettRachel Mwale MwazigheNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis Laporan Kasus Kuntum Rindania T S: Abstrak Latar BelakangDocument12 pagesLeptospirosis Laporan Kasus Kuntum Rindania T S: Abstrak Latar BelakangrindaniakuntumNo ratings yet

- Rheumatic Fever AND Rheumatic Heart Disease: Departemen Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskular FK UsuDocument15 pagesRheumatic Fever AND Rheumatic Heart Disease: Departemen Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskular FK UsuXeniel AlastairNo ratings yet

- Moreillon2004 PDFDocument11 pagesMoreillon2004 PDFMery Luz RojasNo ratings yet

- Paideia Final Paper - Nayunipati - 17-18Document10 pagesPaideia Final Paper - Nayunipati - 17-18api-389379178No ratings yet

- Rheumatic Fever and RHD-SA, HS - FIX PDFDocument48 pagesRheumatic Fever and RHD-SA, HS - FIX PDFSyadza Rhizky Putri AkhmadNo ratings yet

- A History of AIDS Looking Back To See AheadDocument9 pagesA History of AIDS Looking Back To See AheadObginNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia ElderlyDocument13 pagesPneumonia ElderlyAndreaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presentation: by Dr. Raffiq AbbasDocument36 pagesClinical Presentation: by Dr. Raffiq AbbasKarthick UnleashNo ratings yet

- Aroxysmal Atrial Tachycardia With Atrioventricular BlockDocument7 pagesAroxysmal Atrial Tachycardia With Atrioventricular BlockDenisseRangelNo ratings yet

- TS BRANDING ResearchDocument11 pagesTS BRANDING ResearchPARITOSH SHARMANo ratings yet

- RESEARCH TITLE-WPS OfficeDocument9 pagesRESEARCH TITLE-WPS OfficeDaisy Joy SalavariaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Attitude and Student Performance PDFDocument19 pagesTeacher Attitude and Student Performance PDFBachir TounsiNo ratings yet

- Jarrett Graff - PD Reference Letter Spring 2021Document1 pageJarrett Graff - PD Reference Letter Spring 2021api-453380215No ratings yet

- Task 1Document10 pagesTask 1nino tchitchinadzeNo ratings yet

- Teaching NotesDocument13 pagesTeaching NotesmaxventoNo ratings yet

- BlokkdDocument82 pagesBlokkdakarju akNo ratings yet

- CMucat Application FormDocument1 pageCMucat Application FormJiyan Litohon100% (1)

- Supporting Information Emergency MedicineDocument3 pagesSupporting Information Emergency MedicineHaider Ahmad KamilNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Early Measurements of The Distraction Index, Norberg Angle On Distracted View and The of Ficial Radiographic Evaluation of The Hips of 215 Dogs From Two Guide Dog Training SchoolsDocument7 pagesComparison of Early Measurements of The Distraction Index, Norberg Angle On Distracted View and The of Ficial Radiographic Evaluation of The Hips of 215 Dogs From Two Guide Dog Training SchoolsAna CicadaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Language in Childrens Cognitive Development Education EssayDocument9 pagesThe Role of Language in Childrens Cognitive Development Education EssayNa shNo ratings yet

- Final Jury Instructions Seditious Conspiracy Oath KeepersDocument51 pagesFinal Jury Instructions Seditious Conspiracy Oath KeepersDaily KosNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud HoorayDocument4 pagesRead Aloud Hoorayapi-298364857No ratings yet

- Seminar 4 PETRONELA ELENA NISTOR LMA ENG-GERDocument13 pagesSeminar 4 PETRONELA ELENA NISTOR LMA ENG-GERPetronela NistorNo ratings yet

- Artificial PassengerDocument22 pagesArtificial PassengerSiri LahariNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Introduction To Electronics1Document38 pagesLecture 1 - Introduction To Electronics1jeniferNo ratings yet

- Oscar Memoir Speech OutlineDocument4 pagesOscar Memoir Speech Outlineapi-429839178No ratings yet

- Hypnotic Inductions and How To Use Them ProperlyDocument6 pagesHypnotic Inductions and How To Use Them ProperlyRuben Davila100% (1)

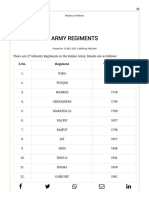

- Army Regiments: S.No. Regiment Year of RaisingDocument3 pagesArmy Regiments: S.No. Regiment Year of RaisingAsc47No ratings yet

- Rohan ResumeDocument2 pagesRohan ResumeRohanNo ratings yet

- Official History of Improved Order of RedmenDocument672 pagesOfficial History of Improved Order of RedmenGiniti Harcum El BeyNo ratings yet

- Intro Pad 101Document43 pagesIntro Pad 101Kemisetso Sadie MosiiwaNo ratings yet

- Stanislavakian Acting As PhenomenologyDocument21 pagesStanislavakian Acting As Phenomenologybenshenhar768250% (2)

- OMS NaturopatiaDocument33 pagesOMS NaturopatiaJoão Augusto Félix100% (1)

- Sexual Reproduction in Plants 5Document77 pagesSexual Reproduction in Plants 5Jujhar GroverNo ratings yet

- PAPER PHYSICS (Kelompok 21 )Document4 pagesPAPER PHYSICS (Kelompok 21 )magfirahNo ratings yet

- The King of The ForestDocument2 pagesThe King of The ForestSeanmyca IbitNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing - Case Digest - Laurel Vs MisaDocument1 pageLegal Writing - Case Digest - Laurel Vs MisaLawrenceAlteza100% (1)

- Initial Diagnosis and Management of ComaDocument17 pagesInitial Diagnosis and Management of Comaguugle gogleNo ratings yet

- Heart Saver Cpr+Aed - HetaDocument2 pagesHeart Saver Cpr+Aed - HetaCharles JohnsonNo ratings yet