Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Uploaded by

Deepanshu ChandraCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Spamming Checks SauceDocument14 pagesSpamming Checks Saucekenishaskinnerz100% (5)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- (BPME3043 - Group B) Dodol Opah Yang Report WebinarDocument29 pages(BPME3043 - Group B) Dodol Opah Yang Report Webinartasya harahapNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Design of Microstrip Patch Antenna For Wireless ApplicationsDocument20 pagesDesign of Microstrip Patch Antenna For Wireless ApplicationsJackNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce Website DesignDocument33 pagesE-Commerce Website Designআশরাফুল অ্যাস্ট্রো100% (1)

- HP Heater 2 NewDocument69 pagesHP Heater 2 NewKuppan SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- 21-11-23 04Document6 pages21-11-23 04chan tanNo ratings yet

- Passivent Natural Ventilation Stategies For Commercial Buildings - UnknownDocument4 pagesPassivent Natural Ventilation Stategies For Commercial Buildings - UnknownwitoonNo ratings yet

- The Automation and Integration of ProducDocument100 pagesThe Automation and Integration of ProducJim GrayNo ratings yet

- Eco Aqua LEDDocument4 pagesEco Aqua LEDthunderhossNo ratings yet

- Design and Kinematic Analysis of The Car JackDocument6 pagesDesign and Kinematic Analysis of The Car JackBerk DemirbasNo ratings yet

- Universign Guide 8.69Document31 pagesUniversign Guide 8.69Yassine DridiNo ratings yet

- Welding ScheduleDocument9 pagesWelding ScheduleAshwani DograNo ratings yet

- Career Objective:: Shubham AgrawalDocument2 pagesCareer Objective:: Shubham Agrawalsubham agrawalNo ratings yet

- Amazon - KagDocument2 pagesAmazon - KagAnirudhNo ratings yet

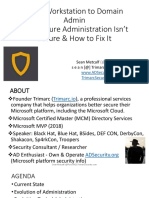

- 2019 Troopers SecuringActiveDirectoryAdministration Metcalf FinalDocument128 pages2019 Troopers SecuringActiveDirectoryAdministration Metcalf FinalFree FoxNo ratings yet

- Subject Name: Design of Machine Members II Class & Specialization: B.tech 3-2, MechanicalDocument1 pageSubject Name: Design of Machine Members II Class & Specialization: B.tech 3-2, MechanicalShashikanth MohrirNo ratings yet

- Expt - No.08 Solar CellDocument8 pagesExpt - No.08 Solar CellRadhika GaikwadNo ratings yet

- Testing Senior EngenierDocument3 pagesTesting Senior EngenierAndrada HalmaciuNo ratings yet

- STI LightCurtain 4600-0030man Eng RevdDocument52 pagesSTI LightCurtain 4600-0030man Eng RevdaferroNo ratings yet

- CMI Accutech BR20 DataSheet V009Document4 pagesCMI Accutech BR20 DataSheet V009Cesar Montes De OcaNo ratings yet

- 62-61753-20 Vector 1550 Tech Man EngDocument261 pages62-61753-20 Vector 1550 Tech Man Engmario100% (1)

- DECK - Lead Nurturing With HubSpotDocument75 pagesDECK - Lead Nurturing With HubSpotHasti GandhiNo ratings yet

- Vertical Integration: Theory and Policy /: Economic Institutions of CapitalismDocument1 pageVertical Integration: Theory and Policy /: Economic Institutions of CapitalismMartin SiriNo ratings yet

- Navio 520Document3 pagesNavio 520Pistrui ValentinNo ratings yet

- 26071-100-VSC-EL4-00024 Rev.00A - WMS Cable Tray InstallationDocument89 pages26071-100-VSC-EL4-00024 Rev.00A - WMS Cable Tray InstallationogyriskyNo ratings yet

- Equivalent Length of Pipe Fittings Table PDF - Google SearchDocument2 pagesEquivalent Length of Pipe Fittings Table PDF - Google SearchzoksiNo ratings yet

- SafeRack Catalog - Industrial Loading Platforms - Safety and Fall Protection Products PDFDocument203 pagesSafeRack Catalog - Industrial Loading Platforms - Safety and Fall Protection Products PDFEdgar_Luggo_Es_7040100% (1)

- M-2 (IoT) 1st SemDocument16 pagesM-2 (IoT) 1st SemBhargav SahNo ratings yet

- Network Layer: Address Mapping, Error Reporting, and MulticastingDocument46 pagesNetwork Layer: Address Mapping, Error Reporting, and Multicastingyuwee yiiiNo ratings yet

- B 1700Document233 pagesB 1700Biram ZdravoNo ratings yet

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Uploaded by

Deepanshu ChandraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Teams Groups Case Assign T

Uploaded by

Deepanshu ChandraCopyright:

Available Formats

Innovation labs are sparking teamwork -- and breakthrough products

(Source: Business Week)

The Razr, Motorola's (MOT ) half-inch-thick, ultralight cell phone, broke a few rules in the industry when it

appeared late last year. t's impossibly compact, simple to operate, and elegant, with an artfully hidden

antenna and impressive photographic capabilities. The phone marked a sleek detour from the drive toward

bulky features, such as powerful storage devices and high-power cameras, that were fattening up phones

and preoccupying rival cell-phone makers. No wonder the Razr has sold a breathtaking 12.5 million units in

less than a year.

But Motorola also had to break some internal rules to get the Razr to market. The biggest: Much of the

critical work on the phone was done at a downtown Chicago innovation lab known as Moto City -- rather

than solely in the company's sprawling traditional research and development facility in suburban Libertyville,

ll. Decorated in a trendy palette of oranges and grays, Moto City fills the 26th floor of a high-rise once

occupied by a dot-com.

To hustle the phone into production, Motorola engineers left their cubicles in Libertyville to team up with

designers and marketers 50 miles to the southeast in Moto City. With its open spaces and waist-high

cubicles for even senior managers, the lab fostered teamwork and a breaking down of barriers -- both of

which contributed to the success of the project. Razr developers, for instance, bypassed a normal process

of running new-product ideas past regional managers across the world. Because they wanted to lead the

market, not just give managers and customers what they thought they wanted, the Razr team put aside

normal practices. "We did not want to be distracted by the normal inputs we get," says Gary R. Weiss,

senior director of mechanical engineering. "t would not have allowed us to be as innovative."

FASTER, FASTER

nnovation labs are a key part of a movement to overhaul old-style R&D. They are designed to complement,

and sometimes even replace, the intensive traditional system -- which required that scientists or engineers

toil away privately for years in the pursuit of patents, then hand their work over to product developers, who

in turn dropped it onto designers' and marketers' laps for eventual shipment out to the public. The leisurely

old handoff approach worked fine a few decades ago, when the likes of Bell Labs and RCA Laboratories

could take years to develop transistors and color TVs, knowing they would enjoy protected markets for

years more. But today's rapacious competition means innovations grow stale fast. Companies must churn

out updates far more quickly. Already, Motorola has unleashed follow-on phones, such as the candy-bar

style Slvr and the rounded, pert-looking Pebl, along with a bevy of novel colors, such as hot pink, for the

flip-top Razr.

Certainly, the need for speed in innovation stretches beyond high-tech companies. Outfits as varied as

Mattel (MAT ), Steelcase (SCS ), Boeing (BA ), Wrigley, Procter & Gamble (PG ), and even the Mayo Clinic

now use such labs to shatter bureaucratic barriers that have grown up among inventors, engineers,

researchers, designers, marketers, and others. Such barriers, say today's management gurus, are an

outdated legacy of Frederick Winslow Taylor, the late-1800s industrial engineer who advocated breaking

down tasks so that different departments could handle jobs successively, leading to the assembly line.

While well suited to the 20th century, the style can only crimp innovators in the 21st century, says Jack

Tanis, director of applied research at Steelcase. Now, "Taylorism is breaking down," he adds.

nstead of assembly line, think swarming beehive. Teams of people from different disciplines gather to focus

on a problem. They brainstorm, tinker, and toy with different approaches -- and generate answers that can

be tested on customers and sped to the market. At times, it's true, innovation labs can seem like dot-com

flashbacks, full of pretentious rhetoric, black-clad engineers, and interior design clichs like cappuccino

machines and foosball tables. But the fact is that the concept has been embraced by companies far

removed from Silicon Valley. These organizations have discovered that innovation labs can be a powerful

tool for big corporations to cut through their own bureaucratic bloat.

A central tenet of the innovation lab movement is that layout and design are crucial. Mattel nc.'s preschool

toy unit, Fisher-Price, has its center at company headquarters in East Aurora, N.Y., but it's clearly a

separate part of the operation. Called the Cave, the center boasts bean-bag chairs, comfy couches, and

adjustable lighting that makes people feel as if they're far from the office. Teams of staffers from

engineering, marketing, and design meet there with child psychologists or other specialists to share ideas.

After observing families at play in the field, they return to brainstorm -- or "sketchstorm," as they call it. Then

they build prototypes of toys from foam, cardboard, glue, and acrylic paint.

Mingling with people from various disciplines has been key at the three-year-old operation. Staffers such as

Tina Zinter-Chahin, senior vice-president for research and development, call the interaction spelunking,

since it's based on an idea of taking a "deep dive" into product development. "People at first were

skeptical," says Zinter-Chahin, noting that toy designers didn't care to spend so much time with marketers.

"They said: 'Come on, 'm going to go away for five days and take a marketing person?' We found that while

they aren't great with foam and glue guns, they're great at hashing out an idea and positioning the product."

Already, Fisher-Price staffers can point to successes. After observing babies as they learned basic skills,

the spelunkers realized that moms spent a lot of time teaching kids about such things in the house as

doors, light switches, drawers, and kitchen utensils. While the company could boast about toys that make

noise or flash lights, it was short on real-world practical stuff. t solved the problem with Laugh and Learn

Learning Home, a $65 model home made of plastic, where kids can crawl through a front door and explore

the alphabet, numbers, music, speech, and different sounds. A smash hit in its 2004 debut, it's now a full

line of toys. The outfit has high hopes for a couple of forthcoming products, such as the Easy Clean high

chair, the result of a spelunk about issues moms had feeding kids.

Although innovation labs are typically created to generate new product ideas, they are also sometimes used

to improve manufacturing processes. At Boeing Co., (BA ) for instance, nearly 3,000 engineers and finance

and program management staffers from scattered locations in the Renton (Wash.) area were moved last

year to the factory where 737 jetliners are assembled. "f you are in the office area, you can feel and hear

the noises in the factory and can look out your window and see the wing tips going down that line," says

Larry Loftis, director of manufacturing for the 737. "There is a constant reminder for the engineers."

Such shifts smooth the way toward faster working arrangements. To urge people to mingle, Boeing created

common break areas where mechanics and engineers can talk shop over coffee or a snack, building

informal relationships that could speed both daily working processes and innovations. Now, if a mechanic

finds that a part doesn't fit, he can find an engineer to redesign it nearly on the spot. Or when a jet with a

novel interior design first rolls on the line, the engineers and mechanics can make changes, as needed.

"When things don't fit exactly right, they can change the engineering or blueprint in hours, instead of weeks

or months," Loftis says.

Such changes aren't always seamless. Older workers, especially baby boomers, may have a hard time

giving up cherished perks such as private offices, say consultants at Steelcase who help design innovation

lab workspaces -- and sell companies the pricey furniture for them. Some workers define their success by

counting ceiling tiles, measuring out the square footage they've got in their private space, and comparing it

with that of others. By contrast, Generation Xers and others new to the workforce more often will trade

privacy for amenities such as in-house recreational areas. Steelcase's design center, for instance, boasts a

waist-high shuffleboard where staffers can unwind.

For some companies, innovation labs are not places where all old ways are killed off once and for all.

nstead, they let employees retreat from their normal workplaces to solve problems and then return

reenergized. Procter & Gamble Co.'s (PG ) Clay Street Project, named for its Cincinnati location, is a haven

where teams of staffers from various disciplines go for stints of 6 to 10 weeks or so to wrestle with product

problems. Free in such comfortable environments, they can look at challenges afresh. "They try to create

transforming breakthroughs," says Roger L. Martin, dean of the Rotman School of Management at the

University of Toronto and a P&G adviser.

Many innovation labs try to encourage the sense, however illusory, that hierarchy has been tossed out the

window. Motorola CEO Edward J. Zander, 58, comes by the company's design center once a week or

more, both because it's close to his downtown Chicago home and because he likes the informality and

energy: Many cell-phone designers are twentysomethings or only slightly older. "The market for handsets

today is young people, and we have a lot of young people here," says Zander, saying the center is "like a

mosh pit."

FAR FROM THE SUTS

ndeed, Motorola broke another rule by locating its center far away from the "suits" in corporate

headquarters, putting it downtown because the spot suited staffers better. Designers can walk down the

street or hop on the subway to see their phones in use. And many of the place's young workers shudder at

the idea of working in Libertyville. " grew up in the suburbs, and didn't want to go back," says Michael

Paradise, a 23-year-old industrial designer.

Consultants who advise companies on such innovation labs are fond of lofts, where high ceilings create a

sense of openness. A lack of walls conveys the idea that communication is free-flowing. And an absence of

private offices suggests that teamwork is the highest priority. "We think everything worth doing is done by

groups, not by individuals," says Tom Kelley, general manager of DEO, a Palo Alto (Calif.) design

consulting firm. He urges an end to rigidly aligned cubicles in favor of loose, eclectic arrangements because

all those cubicles marching ahead in a line "sends a signal that you've got to be on your best behavior."

nstead, he says, people need to feel free to be creative.

To be sure, innovation labs are not panaceas. f the ideas that emerge from these facilities are flawed, the

products undoubtedly will be failures. And if managers don't get behind winning but perishable ideas

quickly, the products could likewise be doomed. But for big companies that are stuck in creative ruts, these

labs can be places where something magical gets started.

Provide SoIutions to the foIIowing questions:

1. What eIements of Team Dynamics modeI are MotoroIa, P&G and other co. appIying to make

these products devept teams (PDTs) successfuI?

2. Identify potentiaI team dynamics chaIIenges the PDTs might face in the situations described

in the case.

3. How are these companies supporting informaI groups and how might these groups aid the

creative process?

4. Anything eIse about the case that captures your attention to think-over?

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Spamming Checks SauceDocument14 pagesSpamming Checks Saucekenishaskinnerz100% (5)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- (BPME3043 - Group B) Dodol Opah Yang Report WebinarDocument29 pages(BPME3043 - Group B) Dodol Opah Yang Report Webinartasya harahapNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Design of Microstrip Patch Antenna For Wireless ApplicationsDocument20 pagesDesign of Microstrip Patch Antenna For Wireless ApplicationsJackNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce Website DesignDocument33 pagesE-Commerce Website Designআশরাফুল অ্যাস্ট্রো100% (1)

- HP Heater 2 NewDocument69 pagesHP Heater 2 NewKuppan SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- 21-11-23 04Document6 pages21-11-23 04chan tanNo ratings yet

- Passivent Natural Ventilation Stategies For Commercial Buildings - UnknownDocument4 pagesPassivent Natural Ventilation Stategies For Commercial Buildings - UnknownwitoonNo ratings yet

- The Automation and Integration of ProducDocument100 pagesThe Automation and Integration of ProducJim GrayNo ratings yet

- Eco Aqua LEDDocument4 pagesEco Aqua LEDthunderhossNo ratings yet

- Design and Kinematic Analysis of The Car JackDocument6 pagesDesign and Kinematic Analysis of The Car JackBerk DemirbasNo ratings yet

- Universign Guide 8.69Document31 pagesUniversign Guide 8.69Yassine DridiNo ratings yet

- Welding ScheduleDocument9 pagesWelding ScheduleAshwani DograNo ratings yet

- Career Objective:: Shubham AgrawalDocument2 pagesCareer Objective:: Shubham Agrawalsubham agrawalNo ratings yet

- Amazon - KagDocument2 pagesAmazon - KagAnirudhNo ratings yet

- 2019 Troopers SecuringActiveDirectoryAdministration Metcalf FinalDocument128 pages2019 Troopers SecuringActiveDirectoryAdministration Metcalf FinalFree FoxNo ratings yet

- Subject Name: Design of Machine Members II Class & Specialization: B.tech 3-2, MechanicalDocument1 pageSubject Name: Design of Machine Members II Class & Specialization: B.tech 3-2, MechanicalShashikanth MohrirNo ratings yet

- Expt - No.08 Solar CellDocument8 pagesExpt - No.08 Solar CellRadhika GaikwadNo ratings yet

- Testing Senior EngenierDocument3 pagesTesting Senior EngenierAndrada HalmaciuNo ratings yet

- STI LightCurtain 4600-0030man Eng RevdDocument52 pagesSTI LightCurtain 4600-0030man Eng RevdaferroNo ratings yet

- CMI Accutech BR20 DataSheet V009Document4 pagesCMI Accutech BR20 DataSheet V009Cesar Montes De OcaNo ratings yet

- 62-61753-20 Vector 1550 Tech Man EngDocument261 pages62-61753-20 Vector 1550 Tech Man Engmario100% (1)

- DECK - Lead Nurturing With HubSpotDocument75 pagesDECK - Lead Nurturing With HubSpotHasti GandhiNo ratings yet

- Vertical Integration: Theory and Policy /: Economic Institutions of CapitalismDocument1 pageVertical Integration: Theory and Policy /: Economic Institutions of CapitalismMartin SiriNo ratings yet

- Navio 520Document3 pagesNavio 520Pistrui ValentinNo ratings yet

- 26071-100-VSC-EL4-00024 Rev.00A - WMS Cable Tray InstallationDocument89 pages26071-100-VSC-EL4-00024 Rev.00A - WMS Cable Tray InstallationogyriskyNo ratings yet

- Equivalent Length of Pipe Fittings Table PDF - Google SearchDocument2 pagesEquivalent Length of Pipe Fittings Table PDF - Google SearchzoksiNo ratings yet

- SafeRack Catalog - Industrial Loading Platforms - Safety and Fall Protection Products PDFDocument203 pagesSafeRack Catalog - Industrial Loading Platforms - Safety and Fall Protection Products PDFEdgar_Luggo_Es_7040100% (1)

- M-2 (IoT) 1st SemDocument16 pagesM-2 (IoT) 1st SemBhargav SahNo ratings yet

- Network Layer: Address Mapping, Error Reporting, and MulticastingDocument46 pagesNetwork Layer: Address Mapping, Error Reporting, and Multicastingyuwee yiiiNo ratings yet

- B 1700Document233 pagesB 1700Biram ZdravoNo ratings yet