Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Focus On The Younger Learner

Focus On The Younger Learner

Uploaded by

Gilberto MaldonadoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Focus On The Younger Learner

Focus On The Younger Learner

Uploaded by

Gilberto MaldonadoCopyright:

Available Formats

Focus on the

Younger

Learner

The Distance Delta

© International House London and the British Council

The Distance Delta Module 3

Focus on the Young Learner

Summary

In this input, we shall look at typical characteristics of different ages of Young Learners. We

shall consider how it appears children learn and analyse some language learning theories

and their relevance for us as teachers of Young Learners. We shall then explore a range of

factors that can affect (whether positively or negatively) children’s learning, both inside and

outside the classroom. We shall consider how their beliefs, motivations and learning styles

are likely to be quite different from adult language learners and how these can impact on

their learning strategies. With all of these things in mind, we shall then explore some

principles of best practice in terms of teaching styles and approaches including behaviour

management, learner training, means of assessment and classroom resources.

Objectives

By the end of this input you will be:

Able to notice and describe differences between Young Learners in terms of their age,

cognitive development, background, exposure to English outside the classroom, how

they learn, their motivation.

Able to demonstrate understanding of the ways you can enhance motivation and

learning opportunities for your Young Learners, taking into account their cognitive and

affective needs as well as knowledge of issues outside the classroom.

1 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Defining the Term ‘Young Learner’

1.2 Differences between Adult Learners and Young Learners

1.3 Characteristics of Different Groups of Young Learners

2 Child Development and Language Learning Theories

2.1 How Children Learn

2.2 First Language Acquisition Theories

2.3 Second Language Learning Theories

2.4 Is There a ‘Best’ Age to Start Learning a Second or Foreign Language?

2.5 Implications of Child Development and First and Second Language Acquisition

Theories for the Young Learner Language Classroom

2.6 The Teenage Brain

3 Local Context and Parental/Guardian Involvement

4 Out-of-class Exposure and Impact on Learning

5 Behaviour Management

5.1 The Importance of Routines

5.2 Pre-empting Behaviour Problems

5.3 Dealing with Misbehaviour

5.4 Promoting Positive Behaviour and Using Praise

6 Learner Training

6.1 Introduction

6.2 ‘Hallmarks’ of a Good Learner

6.3 Strategies Involved in Learning to Learn

6.4 Encouraging Learner Awareness and Responsibility in the Classroom

6.5 Development of Study Skills

6.6 Developing Critical Thinking Skills

7 Learning Styles and Intelligences

7.1 Learning Styles in the Young Learner Classroom

7.2 Mixed Levels and Different Abilities

8 Means of Assessment

8.1 Formal Assessment Versus Learning

8.2 Backwash and Spin-off Effects of Pen-and-Paper Testing on Young Learners

8.3 Evaluating Published Testing Resources

8.4 Implications of Using Pen-and-Paper Tests with Young Learners

8.5 Alternative Forms of Assessment for Young Learners

8.6 Reporting on a Child’s Progress and Attainment to Parents or Guardians

9 Classroom Resources and Teaching Approaches

9.1 Developing Literacy with Young Learners

9.2 Primary and Secondary School Language and Literacy Development

9.3 Adaptation of Published Materials

Reading

Appendices

2 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

1. Introduction

1.1 Defining the Term ‘Young Learner’

Interpretations of the term ‘Young Learner’ vary according to country, culture and

educational context. In the Italian state school system, for example, Young Learners are

divided into 6-10 year-olds attending elementary school, 11-13 year-olds at middle school,

and 14-18 year-olds in secondary school education. In some language schools, the term

refers to anyone under the age of 18 i.e. the age of majority, and they may also accept

children as young as two or three in their Very Young Learner Department. In others, the

cut-off point is earlier and teenagers aged 16 and over are considered part of the school’s

adult population. Although we shall make references to very early years to inform our

understanding of later development in children, the minimum age for a Delta lesson class is

8 years old. Therefore, we shall use the following divisions:

Primary (8 – 10)

Lower secondary (11 – 13)

Upper secondary (14 – 16)

1.2 Differences between Adult Learners and Young Learners

Task 1: Differences between Adult and Young Learners (about 20 minutes)

Reflective Task:

1. Write notes under each of the headings below of your ideas and experiences

regarding some general differences between Adult and Young Learners.

2. Note any implications of these differences for the Young Learner teacher.

Stages of development

Motivation

Capacity to concentrate; tendency to get bored

Development as learners

Life experience

Ability to mimic

Now compare your ideas to the overview below.

3 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Adults Young Learners

Stages of development

There are variations in any class e.g. aptitude for learning, motivation, There may be wide variations in development between children of the same

previous learning experiences etc. age. Development is influenced by family, school, culture and cognitive or

affective factors. Some children are more capable of more logical, deeper and

abstract thinking, or more cooperative with others. Others may just be

beginning to develop these skills.

Motivation

Adults may be learning English for extrinsic or instrumental reasons e.g. Very young children may have no clear reasons for learning English but will

in order to get a (better) job or go up a salary scale. They may learn for engage with it if it is fun. As they grow older, their motivations are often

integrative reasons, because they are living or will be moving to extrinsic, being derived from their parents or other caregivers, who may instil

another English-speaking country. Or, they may be learning for intrinsic in them reasons for learning English as an extra-curricular activity: to help

reasons, because they enjoy the language learning process itself. Of them with their English lessons at school, because it is a universal language

course, some adults will have a mixture of motivations. and will help them get a better job. They also have intrinsic reasons e.g. to be

able to participate in computer video games or understand lyrics of their

favourite bands.

Capacity to concentrate; tendency to get bored

Adults can generally concentrate on a single task for between 15 to 20 Very Young Learners can only concentrate for a very short time on one task.

minutes. Whilst adults can get bored in a language lesson, they have This expands as children grow older with pre-adolescent children able to focus

learnt to deal with this feeling and hopefully their motivation for on a single activity for longer and extending again in most teenagers. The

learning carries them through. They are also on the whole too polite to length of time children can concentrate can be affected by issues such as

show how they feel to the teacher or those around them. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD / ADHD). Children have no choice

but to be in the classroom and have not learnt the societal norms that inhibit

overtly open negative reactions, so they will let a teacher know when they are

bored. Bored children will not focus on the lesson, can be very disruptive and

will develop negative attitudes about their learning experience.

4 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Development as learners

Practically all adults come to the class able to read and write in their Young children are still learning their own language. They may not be able to

own language, with a history of education (whether positive or read in their own language or they may be at very early stages of reading

negative) behind them. Through past experience they have developed development and have very limited skills in writing. They do not have the

attitudes and beliefs about learning and themselves as learners, which same range of language skills to draw upon and apply to the learning of a

may hinder their learning of languages. However, they may have learnt second language as secondary school pupils or adults. They are also still

(whether consciously or subconsciously) some helpful strategies and developing communication skills such as turn-taking and the use of body

techniques for learning, such as ways of memorizing new words or language, as well as motor skills like holding a pencil and hand-eye

rules, and can question what they learn as a means of cognitive coordination. Young children are still open to learning and they tend to have

processing of information. fewer inhibitions than some older teenagers or adults. Children do not begin

to hypothesise or analyse language until they are 10 or 11 years old, although

they can see patterns.

Life experience

The topics we can present in an adult language classroom to provide a A child’s world tends to revolve around the self: children are preoccupied with

motivating context for target language are almost limitless. Adults are their own likes and dislikes, their own family and friends, their own personal

generally also very interested in learning about their classmates as well space or environment, whether in the home or at school. They also have less

as the world around them. knowledge of the world. As they develop, they become increasingly

interested in other topics, whether intrinsically or because it is something they

are learning about at their mainstream school. But their opinions are likely to

be quite ‘black and white’ and spontaneous, rather than reflective.

Ability to mimic

Adults’ ability to pronounce effectively can vary widely, and depends The one area in which children are often superior to adults as language

on their previous language learning experiences. Often, those who learners is in their ability to imitate a pronunciation model. In part it is

have learnt one or two languages before will be better imitators as they because this is what they do in their first language, but also in part because,

have had previous experience of dealing with unfamiliar sounds or especially at a younger age, they are not preoccupied with the need to have a

combinations of sounds. Those who start to learn English later on in complete formal understanding of what they wish to say e.g. parts of speech,

life as their first foreign language experience often take longer to word order, differences between their own language and English etc., but

become more proficient in their pronunciation. more with conveying their immediate message. Being generally

unpreoccupied with how they look and sound to others also contributes to

them enjoying imitating, or even exaggerating models.

5 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Implications of These Differences for the Young Learner Teacher

Stages of development

A Young Learner teacher needs to plan and manage for different levels of ability within one

group. For example, in a group of 8 year olds, some may be competent at cursive writing

and be able to write quite quickly, while others may take a long time to get started on

writing (perhaps because of a disinclination they have for the medium), and others may still

be at the print-writing stage or be slow writers. At the planning stage, you need to consider

exactly why, what and where you wish the children to write. With adult learners, writing is

often seen as a means of consolidation of previous language work, as well as training in the

skill of writing. Given the fact that younger children are still in the process of learning the

finer mechanics of writing, it may be more appropriate to consider other means of

consolidation e.g. giving them word cards to organise into grammatically correct and

coherent sentences, which can then be stuck on larger paper and displayed as a poster in

the classroom. This also means that the children are more likely to be working ‘lock-step’

i.e. everyone finishing the task at around the same time.

Because younger children are still learning how to read in their own language, some are

likely to be more efficient readers in English than others. More confident readers tend to

read in a more logical fashion, reading a whole sentence (rather than just to the end of the

line). Others find it difficult to know how to approach a text in a clear and efficient way to

gain information. This can be quite clear to see in the way their eyes move erratically

around the text as they unsuccessfully attempt to find specific information. They need a

clear and meaningful task to encourage them to read logically and carefully, such as a

competition whereby pairs of students read short definitions of vocabulary they have

recently been learning in order to guess the word and win a point from the teacher, but only

once they have guessed the correct word e.g. ‘People eat this vegetable a lot in soups. It’s

very good for you. You can eat it hot with fish or meat or cold in a salad. It isn’t green and it

isn’t round. Rabbits like this vegetable a lot!’

The Young Learner teacher needs to include activities that cater for various types of learner

because some children are capable of deeper analysis of language, while others have no

interest in this way of studying language. In order to help children understand the various

forms used in a particular tense, e.g. present continuous, the teacher can give students

word cards and get them to come up to the board and complete a large verb table on the

board and then get them to do the same in the table on their coursebook page.

Motivation

It is crucial for teachers to motivate children so they want to learn and can see a purpose in

what they are doing. Children’s motivation and attitudes are central to their initial

engagement and on-going learning. These are promoted by positive relationships with the

teacher, success in foreign language learning, parental attitudes and interesting learning

experiences. The Young Learner teacher is like a sports coach: you need to tell students

when they are improving, and get them to make overt connections between what they are

doing and how this can lead to better results. This is just as, if not more, true for an

apparently ‘weaker’ student as a stronger one. Nothing succeeds like success. However,

praise should be specific to the occasion and the child e.g. ‘You didn’t speak Portuguese at

all in that speaking activity – well done!’ and always deserved rather than an overused and

rather anodyne ‘Great!’

6 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Capacity to concentrate; tendency to get bored

This means that activities should be as interesting, challenging, engaging and varied as

possible. Often the brightest children get bored most easily. Children take their learning

very seriously and will quickly reject that which appears to have no interest or purpose. It is

important to keep in mind the possibility of drops in concentration at the planning stage.

You need to include the following means of keeping students attentive on the lesson plan:

Regular and appropriate changes of activity e.g. from reading task to song

Different patterns of interactions e.g. individual, pairwork and open-class

Change of pace e.g. written question formation activity to small group brainstorming

activity

Variety in seating arrangements e.g. sitting on chairs, mingling around classroom, small

groups working sitting on the floor

Clear and familiar routines e.g. for starting lessons, setting up activities, managing

materials

It is also useful to set time limits for parts of larger stages of the lesson. Although younger

children will not have much of a notion of what, for example, two minutes ‘feels like’,

chivvying them along in this way will give greater impetus to activities, and revive flagging

concentration.

You can also find out if any children in a group have been formally diagnosed with any

learning difficulties, such as dyslexia, Asperger’s Syndrome or ADD (Attention Deficit

Disorder), and how these affect concentration and can be managed in lessons.

For an introduction to dealing with learning difficulties in classes, see

http://oupeltglobalblog.com/2013/07/18/5-myths-about-teaching-learners-with-special-

educational-needs/

Development as learners

A Young Learner teacher needs to be aware of what the children they are teaching will be

capable of and what is beyond them because of their age and level of development.

Use judicious questioning to help further language comprehension. Asking a group of eight-

year-olds to translate a certain expression into their own language may be counter-

productive, as their experience of English expressions and words is so deeply embedded in a

specific context i.e. a story or situation. It could be disruptive to take this language out of

the context with which it is associated.

Choose topics, activities and language forms carefully to suit the child’s age and stage of

development. For example, it takes a certain amount of training to get eight and nine-year-

olds to successfully carry out a closed pairwork information gap activity, such as asking and

answering a partner’s questions and completing a table on a worksheet. They find it

difficult to maintain extended discourse and conversation without the involvement and

intervention of the teacher, they cannot appreciate the concept of wanting to find out

missing information in this way, and writing simultaneously during a speaking/listening

activity is often too cognitively demanding.

A Young Learner teacher is not just someone who develops their language level, but is also

aiming to encourage and develop values such as cooperation, patience and tolerance, as

well as critical thinking skills (organising, categorising, inferring etc). It is also important to

7 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

remember that because younger children do not have the capacity to analyse and

appreciate contrasts in language forms e.g. the present simple and the present continuous,

an overt focus on grammar is likely to be unproductive. That said, teachers can start some

useful learner training in critical thinking skills even with younger children, as we shall see

later on.

Life experience

We can exploit this by relating as much of the content as possible to children themselves

such as my family, my friends, my home, my classroom, my toys, my favourites, my likes and

dislikes etc. Of course, the exact topic depends on their age; as children grow older, they

see beyond themselves and this can be reflected in the topics covered in their classes, for

example fashion, social media or extreme sports.

Ability to mimic

Take advantage of their natural inclination to mimic and incorporate this when drilling, and

make sure you model clearly and naturally. Provide Young Learners with lots of exposure to

the language as well as opportunities for repetition through chants, rhymes, songs, stories

and other language activities.

1.3 Characteristics of Different Groups of Young Learners

In this section we shall explore the key differences and stages of development between

children of different ages. It is useful to have a clear idea of general characteristics that

children of a particular age group have in common to help ascertain the following:

The expectations of the teacher regarding children’s behaviour, interests, levels of

concentration, non-linguistic capabilities, spatial awareness, types of preferred

interactions, sense of responsibility and awareness of their own learning potential.

The manner and roles the teacher should therefore adopt with regard to individuals and

the group as a whole.

The most appropriate activities, approaches, techniques, materials and resources that

should be used to facilitate engaging, efficient and effective language learning.

The minimum age of learners for the purposes of Delta lessons is 8, but we shall

occasionally refer to children younger than this to help contextualise development in Young

Learners generally.

8 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Task 2: Characteristics of Different Groups of Young Learners (about 30

minutes)

The following website provides details of general, physical, social and emotional

characteristics of different age groups (5-7, 8-10, 11-13 and 14-16):

http://www.son.wisc.edu/net/wistrec/net/developstagetext.html

Whilst these characteristics are not specific to language teaching and learning

contexts, there are clear implications for us as language teachers and course

developers. Bear in mind also that these were written for educators working in The

United States.

As you read, consider the implications and make notes on the following:

What learners of each age group need and like.

How well these characteristics describe similar-aged Young Learners in your own

current teaching context.

See Appendix 1

9 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

2 Child Development and Language Learning Theories

2.1 How Children Learn

Task 3: Child Development and Language Learning Theories (about 20

minutes)

Look at these questions and see if you can already answer any of them.

1. Have you heard of the following child psychologists and educators: Piaget,

Donaldson, Vygotsky, Bruner, Egan? If so, what do you already know about them?

2. What does cognitive development involve?

3. What is the difference between assimilation and accommodation regarding the

way a child develops his understanding of the world around him?

4. Do children and adults think in different ways?

5. Are children incapable of thinking logically before the age of 7?

6. Do you think children move through fixed and predictable stages of mental

development?

7. What role can adults play in helping children’s mental development?

8. What does ‘scaffolding’ mean in terms of the help an adult can give a child?

9. Why do children under the age of 10 tend to have a ‘black and white’ view of the

world? For example, why might a child say things like ‘ALL my friends have got

one!’ or ‘You NEVER let me do that!’?

10. Is the concept of understanding typically complete by the age of 16 or 17?

Now read the next section, and compare your ideas to those of the psychologists’

theories below.

Theories of child development and learning have evolved considerably over the last century

and have significantly changed the way children are perceived as active learners in the

learning process. These theories have also affected perceptions of the role of the teacher,

the guardian/parent, as well as heredity and the cultural environment.

In order to become an increasingly principled Young Learner teacher, it is important to have

an overview of background research into the areas of child development and learning

theory, as well as first and second language development. This has clear implications for

how we view our Young Learners, our role in their development and language learning and

the context in which they learn and we teach.

Strange as it seems now, it was once believed that children were unable to think or form

complex ideas, unable to make decisions until they learnt to speak. Of course we now know

that babies are aware of their surroundings and are inquisitive from the time they are born.

From birth, babies begin to actively learn, absorbing and processing information from

around them. They use this data to develop perception and thinking skills. This process

continues into adulthood and is known as ‘cognitive development’: the way a person

10 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of his or her world through the interaction of

genetic and learned factors. Cognitive development involves information processing,

intelligence, reasoning, language development and memory.

The Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980) began to develop his ideas of cognitive

theory in the first half of last century, by watching his own and other children in their own

environment. Prior to Piaget, people tended to think of children as simply small versions of

adults. His work introduced the idea that children's thinking was fundamentally different

from than that of adults. His observations led him to put forward the theory of active

learning or ‘constructivism’, namely, that children build up knowledge for themselves by

making sense of their environment. For example, the young child understands that the

plastic toy he plays with at bath-time is called a duck. When he goes to the park and sees

ducks and geese in the lake, he assumes they are all ducks. This is what Piaget referred to

as ‘assimilation’. The child is assimilating this new experience by relating it to something he

already knows. However, at a later stage, his parents may point out to him that there are

other birds in the park and he will realise that not all birds are ducks. Now he needs to

adapt his way of thinking to allow this new concept to become part of his worldview. This is

what Piaget referred to as ‘accommodation’. Cognitive development involves an ongoing

attempt to achieve a balance between assimilation and accommodation that he termed

equilibration.

Findings from various tasks and experiments conducted with children of different ages led

Piaget to categorise child development of logic into four operational stages:

Source: http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/images/b/b8/Piaget_1.jpg

Pinter (2006) summarises Piaget’s stages thus:

Sensorimotor Stage

The young child learns to interact with the environment by manipulating objects around

him.

11 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Preoperational Stage

The child’s thinking is largely reliant on perception but he or she gradually becomes more

and more capable of logical thinking. On the whole this stage is characterised by

egocentrism, a kind of self-centredness, and a lack of logical thinking.

Concrete Operational Stage

Year 7 is the ‘turning point’ in cognitive development because children’s thinking begins to

resemble ‘logical’ adult-like thinking. They develop the ability to apply logical reasoning in

several areas of knowledge at the same time such as maths, science, or map-reading but

this ability is restricted to the immediate context. This means that children at this stage

cannot yet generalize their understanding.

Formal Operational Stage

Children are able to think beyond the immediate context in more abstract terms. They are

able to carry out logical operations such as deductive reasoning in a systematic way. They

achieve ‘formal logic’.

Cameron (2001) explains this Piagetian viewpoint as follows:

A child’s thinking develops as a gradual growth of knowledge and intellectual

skills towards a final stage of formal, logical thinking. However, gradual growth

is punctuated with certain fundamental changes, which cause the child to pass

through a series of stages. At each stage, the child is capable of some types of

thinking but still incapable of others. In particular, the Piagetian end-point of

development – thinking that can manipulate formal abstract categories using

rules of logic – is held to be unavailable to children before they reach 11 years of

age or more.

Cameron L. Teaching Languages to Young Learners CUP 2001

However, Piaget had his detractors. The Scottish child psychologist Margaret Donaldson

(1978) suggested Piaget underestimated children at the pre-operational stage in believing

that they were largely incapable of logical thinking. She argued that Piaget and his

colleagues used unnatural and ambiguous language and unfamiliar tasks in their

experiments, such as: ‘Are there more yellow flowers or flowers in this picture?’ (Pinter

2006:9). She redesigned some of the original experiments in a more child-friendly format

and demonstrated that ‘when young children are presented with familiar tasks, in familiar

circumstances, introduced by familiar adults using language that makes sense to them, they

show signs of logical thinking much earlier than Piaget claimed’ (ibid). Another criticism was

that Piaget spent too much time describing the typical child, and did not take into account

the individual differences of children, or the differences caused by heredity, culture and

education. It is felt that he put too much emphasis on the individual's internal search for

knowledge, and not enough on external motivation and teachings. He did little research on

the emotional and personality development of children and could have gained more

accurate results if he had viewed cognitive development as gradual and continuous rather

than having definite demarcation stages. (Berger 2008 in

http://thinkingbookworm.typepad.com/blog/2012/03/a-criticism-of-piagets-cognitive-

development-theory.html) Despite such criticisms, most psychologists still support the

existence of some stage-like development in children, albeit less rigid than those suggested

by Piaget.

12 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

While the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky agreed with Piaget that children construct

knowledge for themselves and actively participate in the learning process, he also

demonstrated the impact of social context on children’s development. Irrespective of

Piaget’s stages of development, he was interested in the unique learning potential of the

individual child in conjunction with other people. As Cameron summarises:

Whereas for Piaget the child is an active learner in a world full of objects, for

Vygotsky the child is an active learner in a world full of other people

…[who]play important roles in helping children to learn, bringing objects and

ideas to their attention, talking while playing … reading stories, asking

questions. In a whole range of ways, adults mediate the world for children and

make it accessible to them.

(Cameron 2001:6)

Vygotsky developed the concept of the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’, often referred to

as ZPD. This is the notional gap between the child’s current developmental level as

determined by his independent problem-solving ability and his potential level of

development as determined by the ability to solve problems under adult guidance or in

collaboration with more capable peers.

Source: http://esl.fis.edu/teachers/fis/scaffold/zpd.jpg

Pinter offers the following example to illustrate how this works in practice:

Think of a four-year-old boy who is sitting down to share a story book with a

parent when he notices that the cover page of the story book is full of colourful

stars. He is eager to start counting the stars and is able to count up to about

15 or 16 but beyond that he gets confused with the counting. He will say

things like ‘twenty ten’ instead of thirty, and leave out some numbers

altogether, or just stop, not knowing how to carry on. Left to his own devices,

he will probably abandon the task of counting. However, a parent or teacher,

13 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

or even an older brother or sister, can help him to continue. They can prompt

him by inserting the next correct number or by giving a visual clue (for

example, showing the numbers of fingers) or by pronouncing the first sound of

the word (twenty-fff) that follows. […] Given this kind of help, the child may be

able to count up to 50 or even 100.’

(Pinter 2006:11)

For more on the Zone of Proximal Development, see Carol Read’s blog:

http://carolread.wordpress.com/2011/08/08/z-is-for-zone-of-proximal-development/

This systematic type of support is often referred to as ‘scaffolding’, a term introduced in

1976 by the psychologist Jerome Bruner. This is an instructional strategy that supports a

child in carrying out an activity to ensure that he can gain confidence and take control of a

task or parts of a task when he is ready and willing to do so. Alongside this, the child is also

offered relevant constructive support whenever he gets stuck. In order for learning

development to take place effectively in the ZPD, the parent/caregiver or teacher needs to

ensure the following features are included:

Demonstrating an idealised version of the task (where and when appropriate)

Getting and keeping the child interested in the task

Breaking the task down into smaller steps to make it manageable according to the

needs of the individual child

Avoiding distractions

Encouraging the child with meaningful praise

Keeping the child on track towards the completion of the task, by reminding him what

the task was

Controlling the child’s frustration during the task

Adjusting the type of scaffolding and interaction to the needs of the child as he

becomes increasingly competent

Offering relevant and precise feedback to the child on his performance

The Canadian Professor of Education Kieran Egan (born 1942) has also taken issue with

some of Piaget’s staging, believing that learning should follow the natural way the human

mind develops and understands. He sees educational development as a process of a learner

developing layers of capacity for engaging with the world. Individuals proceed through

different kinds of ‘understanding’ and as they develop, they add new layers of sophistication

without losing the qualities of earlier stages. His ‘understandings’ proceed in this way:

The Somatic Layer (ages 0 – 3/4)

This understanding involves pre-linguistic, physical understandings for which we may not

have adequate verbal means of expression. However, very young, pre-language using

children do have an understanding of the world. This is not an ‘animal’ perception; it is a

distinctively human ‘take’ on the world, composed of how we first make sense with our

distinctive human perceptions, our human brain and mind and heart. In short, it is ‘a

knowledge from the body, beyond human words.’ (Egan cited in

http://reading2live.blogspot.pt/2010/05/on-kieran-egans-educated-mind-chicago.html)

The Mythic Layer (ages 4/5 to 9/10)

14 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

In this stage, emotional characteristics have primary importance. Children need to know

how they feel about whatever they are learning. Fundamental moral and emotional

categories are used to make sense of their experiences, such as good/bad, love/hate,

happy/sad, always/never. Simple binary opposites such as these can be used as a means to

develop further understanding. For example, understanding ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ precedes the

concept of ‘warm’. The story form is a powerful vehicle for learning at this stage, as it

incorporates the categories and processes used by the child in understanding and

interpreting the world: a beginning, a middle, an end, binary opposites, absolute meanings,

emotional and moral connections and metaphors.

The Romantic Layer (ages 8/9 to 14/15)

At this stage, children need to develop a sense of romance, of wonder and awe. Here the

learner is in search of answers to the general question: ‘What are the limits and dimensions

of the real and the possible?’ (Egan 1979:125). Children start to develop initial concepts of

‘otherness’ of an outside world distinct and separate from their own. This separate world is

perceived as potentially threatening and alien. Children are now learning to develop a

sense of their own distinct identity. The romantic learner seeks out the limits of the real

world, looking for binary opposites within which reality exists. So the learner is fascinated

with extremes, and the more different from their own experience and reality, the better.

Typical stories and story forms that children of this age enjoy include a lot of realistic detail

and heroes and heroines with whom they can identify and who embody the qualities

necessary to succeed in a threatening world.

The Philosophic Layer (ages 14/15 to 19/20 years)

At this layer of understanding, learners are developing their capacity to be able to

generalise and organise information. They start to see the world as a unit, of which they are

a part. The meaning of individual pieces of information is derived primarily from their place

within the general scheme of things. Hierarchies are seen as a means of gaining control

over the threat of diversity. Learners become (over-)confident that they know the meaning

of everything.

2.2 First Language Acquisition Theories

For Young Learner teachers, it is particularly useful to have an understanding of how

children acquire their first language because of parallels we can draw in terms of how they

learn English as a second language. Also, depending on their age, children are still likely to

be in the process of learning their mother tongue, so the two processes are to a greater or

lesser degree similar.

As very young children lack the ability to manipulate and think about language in a

conscious way, it is likely that the ways they acquire English will replicate the way they

acquire their first language. Conversely, older children are less likely to learn a second

language purely holistically as unanalysed chunks because of their increasing abilities to

analyse, hypothesize, deduce and use logic in their thinking processes. It is this unanalytical

(as opposed to unthinking) aspect of mastering the mother tongue where language is

subconsciously ‘acquired’, that differentiates it from the more formalised procedures

required in ‘learning’ a second or other language.

Yule defines acquisition as:

15 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

…the gradual development of ability in a language by using it naturally in

communicative situations with others who know the language.

And learning as:

…a more conscious process of accumulating knowledge of the features, such as

vocabulary and grammar, of a language, typically in an institutional setting.

Yule G. The Study of Language: an Introduction CUP 1985

Although very young children cannot verbalise with precision, they are very able

communicators. An 18-month-old child is unlikely to respond to the question ‘Where’s your

teddy bear?’ by saying ‘I believe it is where I left it last night, behind the sofa’. Instead, he

will probably go and get the teddy bear. Children demonstrate understanding and

communicate using their bodies in the early stages of language development. Some parents

use baby sign-language (gestures to convey words such as ‘eat’, ‘sleep’, ‘more’, ‘hug’ and so

on) to help toddlers communicate because gross motor skills are more developed than vocal

skills. Interestingly, children introduced to this method tend to have fewer temper

tantrums as they are better able to express themselves. For more information see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baby_sign_language

Jean Aitchison illustrates the way children acquire their first language with the following

example of a 12-month-old boy called Adam. He used to shriek ‘Dut!’ (meaning ‘duck’) at

bath-time when he knocked his toy duck off the edge of the bath. He only said ‘dut’ if he

knocked the duck off and he never said it when the duck was swimming in the bath. It

appeared the exclamation and the action were part and parcel of a set routine, and could be

better translated into adult language as ‘whoppee!’ or ‘here goes!’ So Adam wasn’t labeling

an object, but the whole scenario. Later on, he would say the magic word when his mum or

dad knocked the duck on the floor. A final stage occurred when Adam disassociated himself

from the whole event and started to use the word with all his ducks regardless of whether

they were being knocked about or not! Later still, the word was used for real ducks, swans

and geese. This example shows how we start to build up our encyclopedic knowledge in our

mental lexicon. (Aitchison 1992)

Young children are not initially aware of the concept of ‘words’. They first extract multi-

word units, for example ‘thatsnotfair’, from the stream of speech around them, store them

and produce them as wholes. Only later do they separate these prefabricated chunks into

their component parts. The words are stored in their mental lexicon both as connected

chunks and individual words. So, using the above example, the word ‘fair’ is stored as both

a word in isolation and as a component of a chunk. The older they get, the more places

(with this meaning alone) this word will appear: ‘fair’s fair’ and ‘fair enough’ to name but

two.

The following cartoon neatly demonstrates the technique of trial and error that children use

in the process of acquiring new language:

16 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Source: http://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/amit/books/lightbown-1993-how-

languages-are.html

When the boy said ‘I putted’ rather than ‘I put’, the error is evidence that he has already

acquired the rule that the past can be shown by adding the inflection ‘-ed’. What has yet to

be acquired is that this verb is irregular. He is trying out his hypothesis of how the past is

formed. Continued exposure of the correct version spoken by other children and adults

subconsciously helps him to adjust his understanding of the rule and will eventually lead

him to produce it correctly. A similar process is at work in the following conversation

extract taken from Crystal 1986:

Marcus: (on a train, approaching London) Are we there yet?

Father: No, we’re in the outskirts.

Marcus: Have we reached the inskirts yet?

Marcus has noticed the prefix ‘out’ and is demonstrating he understands this new word by

using a word that presumably would fit the bill for ‘in a town’. He is using intelligent

guesswork to help further his understanding and creative use of the language.

As well as over-generalising with lexical and grammatical meaning, children are also apt to

under-generalise, as this last conversation extract from Aitchison reveals:

Experimenter: Look at this. It’s an animal.

Brian: No.

Experimenter: Yes, it is.

Brian: No (laughs).

Experimenter: Yes, it is. And this is an animal too.

Brian: No … horsie.

Experimenter: It’s also an animal.

Brian: No.

Experimenter: You don’t believe me.

Brian: No.

(Aitchison 1992: 94)

Brian refused to believe that a horse was an animal. For him, the word ‘animal’ was for a

group of assorted animals, such as the plastic ones he plays with. In all of the above

examples, we can see aspects of Piaget’s theories of ‘assimilation’ and ‘accommodation’ at

work.

17 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

A further way that very young children acquire their first language is through repetition.

Their lives are frequently very routine-focused, with the same language occurring over and

over again. The language connected to these routines is also repetitive and predictable

(getting up, getting dressed, having breakfast etc.). As well as this, children also enjoy

having the same storybooks read to them or singing the same songs. This means they are

exposed to certain phrases over and over again. The same is true for songs or chants which

are often accompanied by actions and gestures. The rhythm helps keep the language ‘alive’

in children’s minds.

Children naturally imitate the phrases and language that they hear around them,

particularly phrases which have exaggerated intonation or rhythm. This appears to help to

perfect the enunciation of sounds as structures tend to disappear in favour of the stressed

words. For example, a sentence such as ‘all the food has gone’ will be reduced to ‘all gone’.

Finally, we cannot forget the impact of praise from caregivers and parents in language

acquisition. The average child will receive enormous amounts of positive reinforcement for

often rather incomprehensible attempts at language production. Parents jump up and

down and rave about the language their child is producing which may be barely

comprehensible to an outsider.

Until fairly recently, it was commonly assumed that a child would have acquired his first

language by the age of 5, albeit with a very limited vocabulary. Cameron (2006) refers to

reports which indicate that full acquisition may not be complete for a further ten years: 11-

year-old children whose L1 is English, for example, tend not to use relative clauses starting

with whose, or a preposition plus relative pronoun e.g. ‘in which’, and clauses introduced

with ‘although’ or ‘unless’ can still be problematic for 15-year-olds. These instances of late

acquisition are not surprising, given what we now understand about child development:

they are features of the language which are frequently written rather than spoken and

express complex logical connections between ideas. Cameron goes on to say that children

aged 7 are still acquiring the skills needed for extended discourse, such as telling stories.

They are still learning how to create coherence and cohesion, and still developing the full

range of uses of pronouns and determiners.

2.3 Second Language Learning Theories

Second Language Acquisition (commonly abbreviated to SLA) is a relatively new field of

research and since there is much debate still about exactly how language is learned, some

issues remain unresolved. There are various theories of second language acquisition, but

none are accepted as a complete explanation by all SLA researchers. There is no one

universally accepted theory of how a child learns his first language, nor do we understand

fully why some children have language disorders.

18 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Task 4: Second Language Learning Theories (about 10 minutes)

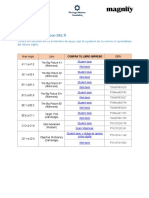

The table below contains the main theories of Second Language Acquisition (SLA). Add

the appropriate theories and the names to the spaces in the table.

Input Hypothesis

Noticing Hypothesis

Mentalism

Behaviourism

Noam Chomsky

Stephen Krashen

BF Skinner

Richard Schmidt

Theory Key Terms Names Dates

imitation, practise, 1957

reinforcement, habit formation

Universal Grammar language 1960s

acquisition device (LAD),

a language instinct

comprehensible input (i+1), 1970s

natural order, critical period and

affective filter, monitor 1980s

hypothesis

the essential point of 1990

acquisition of grammatical

features of a language

See Appendix 2

19 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

2.4 Is There a ‘Best’ Age to Start Learning a Second or Foreign Language?

Task 5: Best Age to Start Learning a Foreign Language (about 15 minutes)

Before you read the next section, write down your answers to these questions, based

on your own experiences of learning a foreign language at school, as well as your

experiences as a Young Learner teacher.

What is the best age to start learning a second language?

What reasons can you think of to support your ideas?

Now compare your ideas with the discussion below.

There is continuing debate as to whether there is an optimum time for someone to start

learning another language. Starting in 1957, Eric Lenneberg proposed the Critical Period

Hypothesis, asserting that the brain’s plasticity was only conducive to language learning

until puberty, because until that time it uses the mechanism that assists first language

acquisition (Pinter 2006:29 and Cameron 2001:13). According to this theory, older learners

will learn language differently, and native speaker-like acquisition can never be fully

attained. However, learners are not learning language in a vacuum, and there are various

factors to take into account, such as whether the child is fully immersed in the second

language environment e.g. a Korean child who has emigrated to Australia with his parents,

or learning in his own country as part of the school’s curriculum. The type of input and

interaction he receives from adults e.g. teachers and caregivers impacts on the degree of

proficiency he may ultimately attain, as does the frequency and length of language lessons

he has, not forgetting of course the quality of the teaching he is given.

Current consensus is that there is no clear cut-off point for successful second language

acquisition; indeed, studies carried out comparing children who started earlier in primary

school with those who started a little later in secondary school show that the advantages of

the early starters tend to diminish by the time they reach the age of 16 (Pinter 2006: 29). Of

course, there are likely to be variations due to the quality of teaching, frequency of lessons

as well as the children’s attitudes towards learning the second language.

The main benefits to starting early appear to be three-fold. Younger children tend to

develop and retain the following:

20 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Good listening comprehension

An intuitive grasp of language

More accurate pronunciation

This is probably because most learning before the age of 7 is aural and oral, and younger

children are arguably more sensitive to the sounds and rhythms of the new language than

older teenagers. As we have discussed earlier, they enjoy copying new sounds and

intonation patterns and are often less anxious and inhibited learners than older children.

However, there is significant evidence to advocate starting studying a language later, since

teenagers are in the process of developing the following:

More efficient strategies for acquiring facts and concepts

Better developed learning strategies and skills

A more mature conceptual world to rely on

A better grasp of grammatical concepts

Greater cognitive maturity

A clearer sense of discourse as they have had more practice at e.g. negotiating, turn-

taking and sustaining conversations

A clearer sense of why they are learning a foreign language

Greater potential to analyse language

Greater potential to pay attention to detail

(Blondin et al in Pinter 2006: 29 and Carol Read Is Younger Better? English Teaching

Professional 2003)

In principle, these factors enable them to make more rapid progress in much less time and

be more efficient learners than young children. Carol Read (ibid) illustrates the negligible

effects of starting young: ‘Penny Ur refers to two classes she taught, one starting at the age

of eight and one at the age of ten, and reports that, by the time they reached 13 and moved

up to secondary school, there was no perceptible difference between the two. Similarly,

David Nunan (2003, cited in Read) reports on language programme evaluations that tested

groups of students aged 15, some of whom started learning English at the age of ten and

some at the age of five, and again found no difference at age 15.’

2.5 Implications of Child Development and First and Second Language

Acquisition Theories for the Young Learner Language Classroom

As you have been working through these materials, you have probably noticed connections

and echoes with your own teaching and students. Indeed, many of the procedures,

techniques, activities and approaches we use are the practical realisation of these theories.

What follows below is a summary of the ways in which theory can be translated into best

practice in the second language classroom.

21 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Task 6: Implications of Theories (about 20 minutes)

Before you read the next section, write down some reasons why the following

statements are important in terms of teaching Young Learners, based on your previous

teaching experience, background reading and opinions. Then compare with the

commentary below.

Teach the new through the familiar

Give children tasks relevant to their stage of development

Focus on language, topics and tasks which are within the cognitive development

and life experiences and interests of the children you are teaching

Engage your students through topics and situations they can relate to

Involve your students as fully as possible to help them relate to the language they

are learning

Make sure your students always understand you

Do not mistake silence for lack of understanding

Focus on your students’ needs, not just the coursebook syllabus

Prepare and set up language tasks carefully to ensure they are manageable

Encourage repetition, imitation and experimentation

Encourage children to make intelligent guesses about language

Encourage children to become ‘language detectives’

Catch your students being good and let them know!

Teach the new through the familiar

Piaget noted that children learnt through a process of assimilation and accommodation.

Here is an example of how this theory can inform practical lesson design and staging:

In Cyrillic script, for example, children are taught to start writing letters from the bottom

and the letters tend to be slanted forwards. This contrasts with Roman script, where

children are taught to start letters at the top and tend to be straight. Young Ukrainian

children who start learning English aged 6 or 7 appear to have relatively few difficulties

writing in English. This is perhaps because they have comparatively little experience of

writing in their own language, and so the Cyrillic script is not fully ingrained yet. However,

children aged 8 upwards learning English for the first time often find Roman script

considerably more challenging, because they already are more practised writers in their

22 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

own language. Whilst the younger children can assimilate the new way of forming letters

surprisingly well, the older children’s longer experience as writers implies the need for them

to accommodate the new style of writing.

Give children tasks relevant to their stage of development

Donaldson’s recasting of several of Piaget’s experiments (Donaldson 1978) shows the

importance of choosing relevant activities and carefully worded supporting questions that

accompany tasks if they are to be effectively carried out by children (see Section 2.1 above).

Transferred to the language classroom, this means students need to be able to readily

understand a task as it reflects their current life experience and also be able to process the

teacher’s instructions without much difficulty.

Focus on language, topics and tasks which are within the cognitive development and life

experiences and interests of the children you are teaching

A class of 8-year-olds is unlikely to be able to talk about ‘regrets’ as they have not had

sufficient life experience nor the linguistic abilities to express such a concept in their own

language. It would be similarly unreasonable to expect them to recount anecdotes in a

clearly organised and coherent fashion because their ability to separate and sequence

events in a chronological order as well as effectively manipulate reference words and

conjunctions is still developing. They tend to use absolutes rather than more balanced

middle shades of meaning in order to argue their case, as in these typical refrains to

parents: ‘you never let me …’ or ‘everyone else has got … except me!’ ‘Rarely’ and ‘hardly

ever’ are examples of mental and linguistic constructs that are later acquired in a child’s first

language.

This is not to say that certain concepts or language forms should be avoided; rather, the

Young Learner teacher needs to have clear reasons and tasks for focusing on certain items

of language, depending on the age of the students, as this example illustrates: a teacher of

primary aged children realises that simply getting pairs of students to ask and answer

questions about their weekend routines with questions and responses such as ‘How often

do you see your grandparents?’ ‘Not very often’ or ‘Nearly every weekend’ is not necessarily

going to be particularly memorable, because these are not the sorts of nuanced responses

they would naturally give in their own language. However, the language focus can be made

more relevant, enjoyable and memorable if the teacher sets up a class mingling activity

whereby the children not only ask and answer these questions, but also record the

responses by completing a simple grid, which they then use to draw a graph. Apart from

reflecting a task they may be familiar with through their maths lessons at mainstream

school, they can take pride in have produced an attractive display for their classroom.

Engage your students through topics and situations they can relate to

A sure-fire way to turn off a class of young teenagers is to announce that their lesson is

going to focus on studying a specific area of grammar. The reason for this is that children

are not normally intrinsically interested in language forms per se, such as present perfect or

concessive clauses, but on what they can do with language, that is how it can enable them

to communicate. Children acquire language through a focus on meaning rather than on

grammatical forms, which is why more effective syllabuses at primary and middle years

have a main focus on topics or situations appropriate to the children’s age and learning

context. Young Learner coursebooks frequently situate language within a cartoon story or

easily recognisable situation, such as ordering food in a fast-food restaurant, and language

practice will involve children repeating chunks of language, rather than close analysis of

form. It is this focus on meaning rather than grammatical forms that facilitates language

23 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

acquisition in younger students. For example, a class of six-year-olds ‘read’ a story taken

from Mini Magic 1 (Esteve and Estruch Macmillan, 2003). Little Elephant complains to

Doctor Monkey of having stomach ache, saying ‘My tummy! My tummy!’ Several lessons

later one of the children looked quite upset, and when the teacher asked what was wrong,

she replied: ’My tummy! My tummy!’, using precisely the same lament and the same

gestures as Little Elephant.

Involve your students as fully as possible to help them relate to the language they are

learning

Teachers need to interact with children to make language and meanings accessible. An

example of this is in reading. There is a parallel to be drawn between a caregiver reading

aloud a bedtime story and the way a Young Learner teacher handles a reading text with a

group of learners. The caregiver will not normally give the child a book to read alone;

instead, she will typically get and keep the child’s attention and interest by sitting near the

child, asking questions and commenting on the storyline and pictures. In a similar manner,

in order for the children to develop relevant language and reading skills, the teacher needs

to mediate in order to get their interest, find out what they can already bring to the text in

terms of related knowledge, as well as help them to interpret the information they hear or

read. The teacher of a group of 9-11 year-olds can ask questions about the plot, the

characters and objects in a story they read and listen to, such as ‘Do you think Colin’s

clever?’ or ‘Why is Clara a good friend to Colin?’ Questions that a teacher might discuss with

an older group of students prior to working on a text about mobile phones could include

‘What are the different functions of your mobile phone?’, ‘What do you most use your

phone for?’ or ‘How do you think mobile phones will change in the next ten years?’

Make sure your students always understand you

Krashen believes language acquisition takes place most effectively when the input is

meaningful and interesting to the learner, and when it is slightly above their current level of

understanding. He calls this level of input ‘i+1’, where ‘i’ represents the level of language

already acquired and ‘+1’ is a +metaphor for language (words, grammatical forms, aspects

of pronunciation) that is a step just beyond that level (Lightbrown P. and Spada N. 2011). It

is important to use L2 i.e. in our case, English so that our students understand us at all

times, even though they may not be familiar with every word. This can be done in

conjunction with gestures, examples, illustrations, experiences, caretaker speech.

If students complain they cannot understand their teacher, it could be that the teacher is

using language at a level too far beyond the students’ current ability to understand, in other

words where the ratio is i+10 or even i+50. This could take the form of using words and

structures that are too advanced for the children’s level of comprehension, as in this

teacher explanation of ‘have to’ to elementary level students whose mother tongue does

not have a cognate for ‘necessary’: ‘You don’t have to wear a uniform means it isn’t

necessary to wear a uniform’. Lack of comprehension can also result from overly

complicated task instructions which are sequenced above the children’s mental, as well as

linguistic, stages of development, as in this example: ‘Before you answer the questions in

your exercise books about this story, I want you to read it quickly and tell me what the story

is about.’ To be fully comprehensible, the teacher needs to divide the instructions into five

micro stages given in chronological order i.e. ‘first: read the story quickly, second: tell me

what the story is about, third: read the questions, four: read the story a second time more

carefully, five: write the answers to the questions in your exercise books.’

The teacher needs to use natural, rather than contrived language with children. Part of

24 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

creating comprehensible input consists of using strategies for making the message

understood, variously known as ‘motherese,’ ‘caretaker speech,’ ‘teacherese,’ or ‘foreigner

talk.’ Some of the characteristics of this speech, as it occurs naturally, will be observed

when a grandparent is talking to a young grandchild or when a skilled teacher is introducing

a new language. Examples of this include elaboration, slower speech rate, use of gestures,

and the provision of additional contextual clues. To make the meaning of ‘I’m an only child’

clear to primary aged children, the teacher could use a combination of these strategies. She

could elaborate by saying ‘I haven’t got any brothers or sisters’, say the sentence more

slowly, to help mitigate any potential difficulties in pronunciation, point to a child in the

class whom she knows is an only child and another who she knows has siblings, and ask

accompanying concept questions: ‘Is Monica an only child?’, ‘Carlos has got a brother’, ‘Is he

an only child?’

Insufficient attention by the teacher to ensuring that messages are always comprehensible

can result in the children becoming demotivated with English classes, because they feel

either that they are no good at English, or that English is just too hard to learn. It is

therefore important for teachers to use planning time to develop effective strategies to

make language comprehensible, be it specific structural or lexical content or classroom-

based language.

Do not mistake silence for lack of understanding

The Silent Period, where learners of a second language do not attempt to speak, is more

common in very young children than in teenagers, as there is often more pressure for them

to speak during the early stages of acquisition. The Silent Period is often associated with

Krashen's Input Hypothesis whereby learners are building up language competence during

their silent periods through actively listening and processing the language they hear, and

that they do not need to speak to improve in the language. A common Young Learner

classroom application of the Silent Period is with the Total Physical Response Method,

which does not require children to speak at an early stage of input of new language; rather,

they are required to listen and observe the teacher’s instructions and gestures, to allow

them time to absorb the new language. What follows is an example of TPR with a group of

10-year-olds and illustrates the carefully scaffolded stages which are key to effectiveness:

The students stand in a circle and watch the teacher;

The teacher tells the children to listen to her and watch her actions. They must not

repeat what she says or does;

The teacher tells a mini story, line by line, accompanied by appropriate mime and

gestures:

It’s a very hot day!

I know! I’ve got an idea!

Put on your swimming clothes;

Put on your shorts and t-shirt and sandals;

Walk to the swimming pool;

Take off your shorts and t-shirt and sandals;

And jump into the pool!

Great!

The teacher repeats the story, and this time the children copy the teachers’ gestures;

The teacher repeats the story, but uses to gestures; the children need to listen and

show understanding by using the correct mime of gesture;

The teacher mixes up the order of the story and the children need to listen carefully and

respond using the appropriate gesture or mime;

25 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Optionally, the teacher can now elicit the language from the students as they start to

tell the story for themselves, all the while using gestures to help move the storytelling

along.

Focus on your students’ needs, not just the coursebook syllabus

Chomsky put forward the concept of a Universal Grammar (UG) to explain the fact children

often produce language that they could not have heard in natural interaction with others,

such as ‘flyed’, ‘writed’ or ‘buyed’. Attaching regular past tense inflection to irregular verbs

is, according to Chomsky, an example of how children make constant hypotheses about the

structure of their mother tongue. This innate metaphorical device allows all children to

acquire the language structure and syntax of their environment during a critical period of

their development. Some theorists argue that it is the Universal Grammar that children

have of their first language which affects language output of second and successive

languages, and accounts for the idea of L1 interference. Without a specific focus on form

differences, students ‘may assume that some structures of the first language have

equivalents in the second language, when, in fact, they do not.’ (Lightbrown and Spada: 36).

Krashen took this idea one stage further with his notion of a natural order hypothesis. Not

only is each child equipped with a set of blueprints (a Universal Grammar) for learning their

first language, there is also a route map for acquiring languages i.e. language is acquired in

predictable stages.

His summary of second language grammatical morpheme acquisition sequence was as

follows:

-ing (progressive)

plural

copula (‘to be’)

auxiliary (progressive as in

‘He is going’)

Article

irregular past

regular past -ed

third person singular s

•(Lightbrown and Spada: 84) possessive s

(Lightbrown and Spada: 84)

26 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

It is perhaps ironic that the features of language that are heard most frequently are not

necessarily the easiest to learn. On the face of it, present simple in the affirmative form

should pose few problems for learners, since they need only remember to add ‘s’ or ‘es’ to

the third person singular forms. Yet it is arguably this simplicity compared to the

grammatical morphology required in other languages that causes this and other deceptively

straightforward features of English to be later, as opposed to early, acquired. This does not

mean that we should therefore delay the teaching of certain structures until such time as

Young Learners are capable of learning them more efficiently. In the case of present simple,

this is certainly an ‘empowering’ structure as it enables them to describe themselves and

others and could also be seen as a gateway for understanding and acquiring other key

structures. What it does mean is that we need to be mindful of the value of recycling,

rather than assuming that if something is ‘taught’ and apparently understood in one lesson,

it will remain in the children’s mind, ready to be accurately produced on demand in a future

lesson. And also to have some empathy with children that seem to persist in making

mistakes which have already been covered in lessons. Lightbrown and Spada illustrate this

point with reference to four stages of acquisition of question forms. They recorded

interactions with a teacher and 11-12 year old French children learning English and found

that drawing a student’s attention to an error and recasting is not going to result in

language improvement if the level of complexity of language is too far above the learner’s

actual level of competence:

S1: Is your favourite house is a split-level?

S2: Yes.

T: You’re saying ‘is’ two times dear. ‘Is your favourite house a split-level?’

S1: A split-level.

T: OK.

(Lightbrown and Spada: 161)

Krashen also put forward the idea of a monitor, a metaphorical ‘editor’ that makes minor

changes and fine-tunes what the acquired system has produced. An example of this would

be a 12-year-old, who has already had quite extensive exposure and practice in talking

about people’s ages. When talking about her sister, she says: ‘Sonia has 9 years old …er …

Sonia IS 9 years old.’ This is evidence that she has already understood that, unlike her own

language, English uses the verb to be with ages, and her ‘monitor’ has interacted to override

what she now understands to be a mistake. Such monitoring takes place when the speaker

(or writer) has time to reflect, is aware of the importance of producing correct, as opposed

to simply understandable, language, and has already learned the relevant rules.

Conversely, however, children are capable of understanding and producing certain language

forms which may not appear in their coursebooks or course syllabus, as long as the message

is highly relevant to them, it has a high surrender value i.e. they will hear and use it

frequently and the children are not expected to be able to analyse and show understanding

of the individual components of the structure. It could be argued that the past tense, for

example, should be part and parcel of the language classroom from an early stage, since this

is a very frequently used structure by native speakers. So even 8 and 9-year-olds in their

first year of learning English can develop an understanding of questions such as ‘Did you

have a nice weekend?’, ‘Did you stay at home?’, ‘Did you go to the beach?’ which their

teacher can ask at the start of lessons and which the children can respond either with a

simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or shake or nod of their heads.

27 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta Module 3

Prepare and set up language tasks carefully to ensure they are manageable

Borrowing from Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, and Bruner’s concept of

scaffolding, language tasks need to be thoughtfully planned and carefully set up to ensure

children are not overloaded or feel that a task is beyond their capability. A simple written

grammar exercise requires just as much scaffolding as does a more elaborate mingling

activity. An example of this in practice which is valid for children of any age who are

capable of focusing on grammatical forms which illustrates many of the features mentioned

in 1.4 above is as follows:

On the board the teacher writes a first example of the grammar manipulation task to be

done and elicits from various students what the task is and clarifies through clearly

checked instructions how to go about doing it.

Students work through a second example, this time the students working from their

coursebooks, but feeding back their answers to the teacher in open plenary again.

Students work through the remainder of the questions by themselves.

Answers are checked at the end when everyone has finished and the teacher offers

constructive feedback to both individuals and the class as a whole.

Encourage repetition, imitation and experimentation

Very young children hear the same expressions from adults and older children over and

over again, and they also repeat many of these for themselves, replicating the same pitch

and tone, deriving pleasure from doing so. Behaviourists would certainly argue that this act

of repetition of language promotes acquisition in children’s first language and is something

we can encourage in the second language classroom. There is value in primary aged

learners repeating tasks, games, songs and chants from one lesson to another; if it is an

activity they enjoyed in one lesson, the chances are they will enjoy doing it again in another,

with the added benefit that the act of delayed repetition is likely to improve their

performance too. However, the teacher needs to exert judgment to ensure the children do

not get bored with too much repetition.

Similarly, with middle-school aged children, the act of choral drilling can be one way of

promoting automaticity, which is ‘the ability to perform a task without conscious or

deliberate effort’ (scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2012/02/26/a-is-for-automaticity/), and

can be made fun by getting Young Learners to say the target language loudly, then slowly,

then quickly, then happily and finally quietly.

Far from merely parroting the language children hear around them, they can be very

creative and enjoy playing with words. As Pinter points out: ‘They make up their own

words, create jokes, and experiment with language even when they have to rely on limited

resources.’ She cites the examples of one native English-speaker child calling a cactus a

‘hedgehog flower’, and another referring to a Dalmatian as a ‘dog with chicken pox’. (Pinter