Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aristotle S Ethics Outline

Uploaded by

Mohsen Haj HassanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aristotle S Ethics Outline

Uploaded by

Mohsen Haj HassanCopyright:

Available Formats

Aristotle (384-322 BC) OUTLINE

ARISTOTLES ETHICS: THE PRIMACY OF REASON I. LIFE AND INFLUENCE Aristotle could be considered as the culmination and, perhaps, the best expression of Classical Greek Culture and Learning. Joined Platos Academy at age 17; and studied at this Academy for 20 years (until Platos death in 347 B.C.) Traveled to Assos and Lesbos (where he collected a wealth of biological data) and to Macedonia (where he taught Alexander the Great.) Returned to Athens in 335 B.C. and established his own school (called the Lyceum). Alexander died in 323 B.C.; Aristotle decided to flee from Athens because of the strong antiMacedonian feelings prevailing at that time. He died a year later at the age of 62. Aristotle left an enormous body of writings which include works in Biology; Logic and Semantics; Physics; Psychology; Metaphysics; Ethics; Politics; Rhetoric; and Poetics. Cataloguers also list under Aristotles name some 158 constitutions of Greek states. II. ARISTOTLES PHILOSOPHY CONSTITUTES A COHERENT WHOLE; A SYSTEM; A WORLD VIEW. III. ARISTOTLES VIEW OF THE WORLD (Metaphysical Doctrines) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Teleology (purposefulness). Order, Lawfulness, Great Chain of Being Potentiality Actuality. Change as increase in order and organization. Everything has its proper Essence. Reason can discover the order in the world. (The Socratic tradition).

IV. ARISTOTLES VIEW OF HUMAN NATURE 1. Aristotles view of the human personality. The two parts of the soul: the rational and the non-rational. Rationality as the essence of the human person. 2. Human Beings, by nature, are neither good nor bad; but they are educable. Habit and training could be used for the development of natural predispositions and capacities. Habit cannot change the nature of a thing. Human beings, by nature, are social beings. 3. Virtues are character traits. Once fully developed and inculcated, the virtues operate as strong predispositions to act in certain ways. 4. How do we measure the moral strength of a persons character? Is the strength of persons moral character directly proportional to the strength of the evil inclinations and temptations that this person successfully resists in order to do the morally right thing?

Successful acquisition of the right habits renders doing the right thing almost automatic. Paradox: by becoming perfectly moral you cease to be moral! V. EUDAEMONIA (well being or happiness). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The distinction between a theory of value (what sorts of things are deemed good, desirable, or sought after?) and a theory of moral obligation (what are we morally obligated to do or refrain from doing, and why?). Aristotle: "Every action aims at some good". The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic good. According to Aristotle not all goods can be extrinsic; there has to be at least one sort of thing which is intrinsically good. The ultimate good (or end) for human beings is happiness. Joint or collaborative human activities also aim at some goods. Aristotles notion of a profession or practice. Aristotles distinction between goods that are external to the profession and goods that are internal to it. Healing and alleviation of pain that a physician may be able to bring about are goods that are internal to the practice of Medicine. However, wealth or fame are goods that are external to the practice of Medicine because they could be attained by practicing other professions or performing other activities. Emphasis on pleasure and happiness does not necessarily lead to hedonism. Pleasure accompanies virtuous activity. On virtue and pleasure: does it pay to be virtuous? Aristotle: By becoming virtuous you become the sort of person who is likely to be happy. Question: What if the unjust flourish?!

6. 7.

VI. THE PRIMACY OF REASON. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The importance of the assumption that rationality is unique to human beings. Reason should control feelings and emotions. Example: Fear (an emotion) when properly controlled by reason results in courage (a virtue). When fear is uncontrolled by reason, the result is a vice: rashness or cowardice. The doctrine of the Mean: Excess and deficiency are both irrational (hence, both are vices). A virtue is a mean falling between two extremes. How do we determine (locate) the mean? Aristotles contextualism: The determination of the mean in specific cases is left to "perception". Aristotelian Ethics as an Ethics of Virtue.

VII. ON BEING FULLY HUMAN. 1. 2. 3. 4. Implications of the principle of the subordination of the non-rational to the rational. Degrees of rationality and hence of humanity! The issue of slavery. The subordination of women. The connection between leisure time and creativity.

VIII. SELF REALIZATION. 1. 2. 3. Aristotelian Ethics as an Ethics of Self-Realization. The Aristotelian Principle: Greater value and satisfaction are achieved by realizing more complex potentials. If you have the potential to excel at playing chess, is it wrong to play only checkers? Who determines what my true potential is? THE CULT OF REASON

IX. CONCLUDING QUESTION: Can we avoid the moral anarchy of the Sophists without endorsing Platos dictatorship of the Wise?

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- American University of Beirut Mathematics Department-FASDocument11 pagesAmerican University of Beirut Mathematics Department-FASMohsen Haj HassanNo ratings yet

- Chem 1Document28 pagesChem 1Mohsen Haj HassanNo ratings yet

- Chem 2Document17 pagesChem 2Mohsen Haj HassanNo ratings yet

- Experiment 4Document30 pagesExperiment 4Mohsen Haj HassanNo ratings yet

- CJGA Color TheoryDocument2 pagesCJGA Color TheoryMohsen Haj HassanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NEERJA 7th April 2016 Pre Shoot Draft PDFDocument120 pagesNEERJA 7th April 2016 Pre Shoot Draft PDFMuhammad Amir ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument7 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledYanna ManuelNo ratings yet

- Baggage Handling Solutions LQ (Mm07854)Document4 pagesBaggage Handling Solutions LQ (Mm07854)Sanjeev SiwachNo ratings yet

- Ati - Atihan Term PlanDocument9 pagesAti - Atihan Term PlanKay VirreyNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Plan GuidelinesDocument23 pagesEnvironmental Management Plan GuidelinesMianNo ratings yet

- Aradau Security Materiality SDDocument22 pagesAradau Security Materiality SDTalleres NómadaNo ratings yet

- Lord Chief Justice Speech On Jury TrialsDocument10 pagesLord Chief Justice Speech On Jury TrialsThe GuardianNo ratings yet

- Literature Component SPM'13 Form 4 FullDocument12 pagesLiterature Component SPM'13 Form 4 FullNur Izzati Abd ShukorNo ratings yet

- ConsignmentDocument2 pagesConsignmentKanniha SuryavanshiNo ratings yet

- Facilitators of Globalization PresentationDocument3 pagesFacilitators of Globalization PresentationCleon Roxann WebbeNo ratings yet

- Suffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsDocument44 pagesSuffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsGrant ParpanNo ratings yet

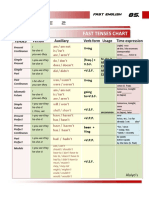

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDocument5 pagesTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNo ratings yet

- Romanian Architectural Wooden Cultural Heritage - TheDocument6 pagesRomanian Architectural Wooden Cultural Heritage - ThewoodcultherNo ratings yet

- XZNMDocument26 pagesXZNMKinza ZebNo ratings yet

- Dewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Document2 pagesDewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Dewi Handariatul MahmudahNo ratings yet

- RA-070602 - REGISTERED MASTER ELECTRICIAN - Manila - 9-2021Document201 pagesRA-070602 - REGISTERED MASTER ELECTRICIAN - Manila - 9-2021jillyyumNo ratings yet

- Us and China Trade WarDocument2 pagesUs and China Trade WarMifta Dian Pratiwi100% (1)

- Offer Price For The Company Branch in KSADocument4 pagesOffer Price For The Company Branch in KSAStena NadishaniNo ratings yet

- EC-21.PDF Ranigunj ChamberDocument41 pagesEC-21.PDF Ranigunj ChamberShabbir MoizbhaiNo ratings yet

- Gothic Voodoo in Africa and HaitiDocument19 pagesGothic Voodoo in Africa and HaitiJames BayhylleNo ratings yet

- Mun Experience ProposalDocument2 pagesMun Experience Proposalapi-296978053No ratings yet

- X3 45Document20 pagesX3 45Philippine Bus Enthusiasts Society100% (1)

- 4th Exam Report - Cabales V CADocument4 pages4th Exam Report - Cabales V CAGennard Michael Angelo AngelesNo ratings yet

- Horizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationDocument12 pagesHorizon Trial: Witness Statement in Support of Recusal ApplicationNick Wallis100% (1)

- Small Hydro Power Plants ALSTOMDocument20 pagesSmall Hydro Power Plants ALSTOMuzairmughalNo ratings yet

- Specific Relief Act, 1963Document23 pagesSpecific Relief Act, 1963Saahiel Sharrma0% (1)

- Chaucer HumourDocument1 pageChaucer HumouranjumdkNo ratings yet

- Transportation Systems ManagementDocument9 pagesTransportation Systems ManagementSuresh100% (4)

- Principle Mining Economics01Document56 pagesPrinciple Mining Economics01Teddy Dkk100% (3)

- Account Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceDocument4 pagesAccount Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceAhsan ShabirNo ratings yet