0% found this document useful (0 votes)

282 views52 pagesChapter 2 Stress Tensor

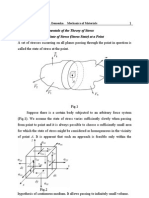

The document provides a comprehensive overview of the stress tensor in continuum mechanics, detailing the definitions and components of stress, including normal and shearing stresses. It explains the significance of stress components on various planes and introduces the concept of stress transformation, principal stresses, and special cases such as triaxial and uniaxial stress. Additionally, it outlines the sign convention for stress and the conditions for equilibrium in stress analysis.

Uploaded by

aditgajurel797Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

282 views52 pagesChapter 2 Stress Tensor

The document provides a comprehensive overview of the stress tensor in continuum mechanics, detailing the definitions and components of stress, including normal and shearing stresses. It explains the significance of stress components on various planes and introduces the concept of stress transformation, principal stresses, and special cases such as triaxial and uniaxial stress. Additionally, it outlines the sign convention for stress and the conditions for equilibrium in stress analysis.

Uploaded by

aditgajurel797Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd