Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Small Business Strategies (English)

Uploaded by

Nova EkayantiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Small Business Strategies (English)

Uploaded by

Nova EkayantiCopyright:

Available Formats

SMALL BUSINESS STRATEGIES: REFINING STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT THEORY FOR THE ENTREPRENEURIAL AND SMALL BUSINESS CONTEXTS

ABSTRACT Research in entrepreneurship has debated the differences between entrepreneurial and small business ventures for quite some time, arguing that entrepreneurial ventures are small growth oriented, strategically-innovative firms, while small business ventures are neither growth oriented nor strategically innovative. However, scholars often treat both types of ventures analogously in terms of both construct and theory, which poses clear problems given their differences. As a result, we may have missed opportunities to advance both our understanding of new firm survival and growth and our understanding of how theoretical perspectives in strategic management apply to entrepreneurial and small business ventures. Since we understand far less about the strategies of small firms than the strategies of large firms, these problems present a substantial opportunity to refine strategic management theory for the entrepreneurial and small business contexts. Thus, in this study we examine the extent to which small firms may engage in strategic pursuits of competitive advantage to determine the applicability of strategic management theories to the contexts. We do so by empirically examining the types of strategies employed by entrepreneurial and small business ventures. Contrary to common assumptions, we find the essence of small

firm strategy is to stay small. We discuss the implications of our findings for future research and practice.

INTRODUCTION What do Apple, Dell Computer, Microsoft, and McDonalds all have in common? They all started as small businesses. While virtually all businesses start out small (Aldrich & Auster, 1986), many never move beyond small business ventures, which are businesses that are independently owned and operated, not dominant in its field, and does not engage in any new marketing or innovative practices, while a select few become entrepreneurial ventures which pursue profitability and growth through innovative strategic practices (Carland, Hoy, Boulton, & Carland, 1984: 358). Yet, strategic management theories at their essence are growth-oriented (e.g. Penrose, 1959) and the predominant assumption is that small firm strategy should be growth oriented as well (Aldrich & Auster, 1986; Covin & Slevin, 1989; Merz, Weber, & Laetz, 1994). However, 99.5% of all businesses in the U.S. (U.S. SBA, 2007) are defined as small, with the overwhelming majority of firms being neither growth-oriented nor strategically innovative (Carland et al. 1984). In fact, only a very tiny fraction of small businesses ever grow into successful large firms (Bracker & Pearson, 1986). This gap between the theories in strategic management and the business contexts, to which they are applied, raises an important question: Do the growth-seeking tenets of strategic management theory apply only to 0.5% of firms in the U.S., or do our theories also apply to the context of small business?

Entrepreneurial ventures and small businesses both play important roles for economic growth and job creation in society (Solomon, 1986; Storey 1994). Given their importance, can we accept the Carland and colleagues (1984) assertion that small firms are neither innovative nor strategic? If we assume that most firms face competition of some sort, then should not all such small firms theoretically pursue some form of strategy? If so, most prior research on small firm strategy, which tends to lump non-growth-oriented small firms with growth-oriented firms, may have missed substantial opportunities to understand better, how theoretical perspectives in strategic management apply to entrepreneurial and small business ventures. Specifically, we believe opportunities have been missed to: 1) Differentiate forms of strategy among different types of small firms; and 2) To help explore the relevance and applicability of strategic management theories to the context of small firms. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to explore the types of strategies that small firms may theoretically pursue and then to test how these strategies may affect their performance. Through this study, we seek to contribute by (1) examining the extent to which small firms may engage in strategic behaviors to determine the applicability of strategic management theories to the contexts; (2) improving our understanding of the effectiveness and performance implications of different strategies for the context, and, (3) enriching our understanding of the strategic management practices that dominate economic activity.

We organize this paper in the following manner. First, we explore important differences between small and large firms to determine how these differences might affect the applicability of strategic management theories and the strategy choices available to small businesses. Then we examine specific approaches to strategy preferred most strongly by small businesses (NFIB, 2003) and test hypotheses relating these strategy approaches to performance measures. We then present and discuss our results and conclude with implications for researchers and practitioners.

THEORY DEVELOPMENT Small Firms, Large Firms

In the United States, a business is defined as small if it has 500 or fewer employees (U.S. SBA, 2007). Two primary reasons why small firms exist are: (1) to provide goods and services to satisfy customers needs in a manner that they will continue to use and recommend the firms goods and services (i.e. customer service business) and (2) to create desired goods and services so that the investment in the firm is converted to cash as quickly as possible (i.e. cash conversion business) (Reider, 2008: 17). This emphasis on fostering repeat customers (sustainability) and steady cash flow (rent accrual) indicates that (successful) small firms pursue strategic behaviors, and helps to explain how small firms survive, but not necessarily why they remain small. However, there are a number of other factors that limit small firm

growth. This is because small firms have scale, scope, and learning liabilities and disadvantages relative to large firms (Stinchcombe, 1965; Welsh & White, 1981).

For example, small firms tend to produce a small volume (scale) of a few products (scope) and typically have a limited capacity for acquiring knowledge (learning) (Nooteboom, 1993). Small firms differ from large firms in that they are often resource poor (Welsh & White, 1981) and therefore require different approaches to strategy, especially in the early stage of a firms existence when the two most important issues are survival and growth (Aldrich & Auster, 1986). Smaller and younger firms both have limited resources that are also less valuable than those possessed by larger and older firms. One reason for this is that smaller and younger firms pay lower wages and offer lower returns to their employees (Oosterbeek and Van Praag, 1995; Van Praag & Versloot, 2007; Wunnava & Ewing, 2000), they employ individuals with lower levels of human capital (Troske, 1999; Winter-Ebmer & Zweimuller, 1999), and realize lower levels of capital-skill complementarity (Troske, 1999) than larger and older firms do. This relative scarcity of resources in small and young firms makes them more vulnerable to external threats and internal missteps than larger and older firms (Moore, 2001).

Despite differences in resource endowments between small and large firms, small firms do have advantages. First, it is much easier for a small firm manager to attend to the countless details in running a competitive business when the business is small and the details involve only a handful of employees and (Slevin & Covin, 1995). Therefore, unlike the managers in most large firms, the manager(s) of small firms have the ability to influence directly the performance of their organizations (Wiklund, 1998). Further, in many small firms the owner is typically very personally involved (often as the hands on manager), has often made a high investment in the business, and has motives for the firm other than simple maximization of shareholder returns (Reid & Smith, 2000). Small firms can also often adapt more quickly and benefit more effectively to changes in the environment than large firms can (Slevin & Covin, 1995). For example, recent consolidation of the banking industry, has created a dissatisfied, underserved customer base opening opportunities for small local and regional banks, who can provide much better customer service (Tatge, 2003). Given these advantages, small firms are often better off using their simplicity, flexibility, and ability to respond to opportunities more quickly than large firms and/or by specializing in niche markets where they can avoid head-to-head competition with larger, more resource rich, firms. In general, smaller firms have been successful by identifying and exploiting niches in specialization, quality, size (produces only small lots), price (sell at a discount all the time), service (high level of service), and location (limits itself to certain geographic boundaries) (Kotler & Turner, 1989).

From a strategic management standpoint, small firms create an environment in which both the opportunities and constraints are different from those in large organizations (Cooper, 1981). Small firms go through stages inception, survival, growth, expansion, and maturity differently than large firms that pose unique challenges to their managers (Scott & Bruce, 1987). And most small firms, may not even experienced all the stages of a firms life cycle (some indeed may reach maturity without ever going through growth or expansion) that their larger counterparts have (Churchill & Lewis, 1983). Unlike larger and older firms, which have experience significant growth and expansion, enjoy economies of scale and/or scope, and have achieved the stage of resource maturity (Churchill & Lewis, 1983; Scott & Bruce, 1987), most small firms are not growth-seeking and age to maturity operating persistently in the stage of survival, often until they fail due to an insufficient financial reward to remain in business or a lack of willingness to continue operating the firm (van Praag, 2003).

Small Firm Strategies

As we have discussed thus far, because small firms vary substantially in their resource positions (Cooper, 1981), the goals and objectives of their founders (Carter, Gartner, Shaver, & Gatewood, 2003; Evans & Leighton, 1989; 1990), and their potential for survival and interests in growth (van Praag, 2003), small firms will also likely vary substantially in the types of strategies they pursue. However, growth is a

core assumption of strategic management theories, yet as we have argued previously, for a variety of reasons, the vast majority of firms are and remain small, pursuing strategies to survive, either not wishing to, or not successfully pursuing and achieving the growth strategies of large firms. Such strategies for survival may be characterized by tactics such as using minimal overhead (Ebben & Johnson, 2006; Winborg & Landstrom, 2001), choosing an attractive industry (Stearns, Carter, Reynolds, & Williams, 1995), and building a loyal customer base (Liao & Chuang, 2004).

Conversely, strategies for (small firm) growth may be characterized by tactics such as a focus on management and workforce training to grow the size of the employee base, issuing equity to external stakeholders to fund growth, developing technological sophistication to monitor and manage growth, seeking flexibility to adjust to new and changing markets, and introducing new products (Storey, 1994). Since most small firms appear to pursue survival strategies (Carland et al. 1984), and survival predominately depends upon a loyal customer base (Reider, 2008), we decided to narrow our scope of small business strategies to focus on exploring two strategic approaches consistent with building a loyal customer base -- providing the highest possible quality, and providing better customer service (Liao & Chuang, 2004). Since another strategic approach to small business survival includes minimal use of resources (Ebben & Johnson, 2006; Winborg & Landstrom, 2001), we also retain this approach within the scope of our study. In the next sections, we review the literature on these different strategies and offer testable hypotheses about the

relationship between their use and a small firms ability to survive and grow. Through examining the relationship between these dominant small business strategies and their effects on survival and growth, we can shed some light on the differences and applicability of strategic management theory to the small business context.

Hypothesis 1 - High Quality Differentiation and Firm Survival and Growth

A firm is able to differentiate itself from competitors if it can be unique at something that is valuable to customers beyond simply offering a low price (Porter, 1985). One way of perhaps the most common was for a firm to differentiate itself from its competitors is to offer products or services at a higher level of quality. Such differentiation can lead to competitive advantage and superior performance when the price premium for the differentiation exceeds its additional costs (Porter, 1985). The resource-based view also suggests that in order to achieve superior performance through differentiation, a firm must possess and use valuable, rare, costly to imitate, and nonsubstitutable resources in its strategy (Barney, 1991, 2001). Because small businesses are resource constrained, they must rely on individual-specific resources to compete against larger firms (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001). Individual-specific resources can be an advantage for small firms because it is easier for managers to organize their limited resources in ways that concentrate on fulfilling the needs of a small customer base (Morris, 2001). As argued earlier, on

advantage of small businesses over large businesses, is that managers of small firms are better able to focus on running a totally competitive business with only a handful of employees because their size and control allows adaptability and rapid response (Slevin & Covin, 1995). Based on these arguments, we expect differentiation strategies based on high quality to be positively related to at least minimum levels of sustained firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through survival) in small firms. Stated formally: Hypothesis 1a: The extent to which a small firm follows a high quality differentiation strategy will be positively related to survival.

However, if firms who offer a high level of quality in their products and services seek to grow, they must achieve awareness of their brands in order to reduce advertising costs and improve customer loyalty. Brand awareness is a dominant choice heuristic in the consumer choice process (Hoyer & Brown, 1990). Firms advertise with the expectation that increasing awareness about their brands will increase the likelihood of a consumer purchasing their product and in turn lead to sales growth (Bogart, 1986). Because smaller firms may have a liability of newness (Stinchcombe, 1965) and/or have limited resources for advertising, they are less likely than established, larger firms are to build brand awareness among customer groups. Further, sales promotions such as advertising are discrete activities that tend to have short-term and immediate effects on sales (Neslin, 2002). Therefore, a small

or new firm may not be able to build brand awareness through advertising alone, even if it possessed the resources. Therefore, a differentiation strategy, based on high quality, is perhaps of more importance for a smaller, or newer, resource constrained firm as they do not have the resources to build perceived brand awareness, they can only build brand awareness through reputation and word of mouth. Based on these arguments, we expect differentiation strategies based on high quality to also be positively related to at least minimum levels of sustained firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through growth) in small firms. Stated formally: Hypothesis 1b: The extent to which a small firm follows a high quality differentiation strategy will be positively related to expected growth.

Hypothesis 2 - Customer Service Differentiation and Firm Survival and Growth Outstanding customer service involves providing a level of service so friendly, efficient, and professional that your customers expectations are exceeded and they look forward to doing business with your firm again (Reider, 2008: 78). Given that the consumer experience is as important as, if not more important than, the consumer good (Bowen & Waldman, 1999: 164- 165), one of the advantages of small firm size is the ability to provide a personal touch to the customers experience (Gross, 1967). Front-line service employees who reside at the interface of the firm and the customer represent the face of the firm to its customers and play a critical role in service encounters (Solomon, Suprenant, Czepeil, & Gutman, 1985).

To the extent that employees are able to deliver high-quality services, customers are more likely to have favorable evaluations of service encounters, experience higher satisfaction, and increase their purchases and the frequency of their future visits (Borucki & Burke, 1999; Bowen, Siehl, & Schneider, 1989; Liao & Chuang, 2004). The favorable evaluations, high customer satisfaction, and increased visits and purchases should increase both the likelihood that a small firm will be able to grow. Therefore, based on these arguments, we expect differentiation strategies, based on customer service, to be positively related to at least minimum levels of sustained firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through survival) in small firms. Stated formally: Hypothesis 2a: The extent to which a small firm pursues a high customer service strategy will be positively related to survival. Further, we expect differentiation strategies based on high customer service to also be positively related to at least minimum levels of sustained firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through growth) in small firms. Stated formally: Hypothesis 2b: The extent to which a small firm pursues a high customer service strategy will be positively related to expected growth.

Hypothesis 3 - Minimal Resource Strategies and Firm Survival & Growth

A small firms reliance on minimal resource stocks is a commonly used form of bootstrapping (Winborg & Landstrom, 2001). Bootstrapping is a process of using the minimum possible amount of all types of resources at each stage in a firms growth (Stevenson, 1984; Timmons, 1999). This approach is attractive to small firms given their resource poverty positions because it reduces some of the risk they face in pursuing opportunities by minimizing financial risks, sunk costs, and fixed costs while optimizing flexibility (Timmons, 1999). Bootstrapping is essentially a mindset in which the small firm owner begs, borrows, or scavenges the resources it needs at the time it needs them, instead of accumulating them beforehand (Starr & MacMillan, 1990). Like entrepreneurship, bootstrapping is an iterative process based on a multistage commitment of resources with a minimum commitment at each stage or decision point (Timmons, 1999: 322) and investing only if conditions are favorable (McGrath, 1999).

One advantage of a minimal resource bootstrapping strategy gives small firms access to and control of resources without having to own them (Bygrave & Zacharakis, 2008). In practice, however, entrepreneurs tend to turn to bootstrapping strategies when they perceive the risk associated with their new firms to be high (Carter & Van Auken, 2005). In other words, small firm managers may turn to bootstrapping when they believe their firms are in danger of failing. At the same time,

in small service and retail businesses that are at the end of the value chain, performance variation may be better explained by limited or poorly developed resources than by a firms choice of strategy (Brush & Chaganti, 1999). This line of reasoning suggests that entrepreneurs who minimize their resource bases are either on the verge of failing or do not have access to resources of sufficient quality or quantity to make the business succeed. Therefore, based on these arguments, we expect minimal resource strategies, to be negatively related to firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through survival) in small firms. This leads to the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 3a: The extent to which a firm relies on a minimal resource strategy will be negatively related to firm survival.

A firm employing a minimal resource strategy also has the advantage of fewer sunk and fixed costs, which provides the firm with more degrees of freedom for how to use its resources (Winborg & Landstrom, 2001). Small firms that learn how to deal with resource limitations through their customer and supplier relationships can develop routines that incentivize customers to pay up front or earlier and to delay payments to suppliers until the last day possible (Ebben & Johnson, 2006). Not all small firms will be able to develop such routines, however, because of differences in their accumulation of experience and how they codify their experience into organizational routines (Zollo & Winter, 2002). A small firm that is able to develop

these routines creates some leverage with its customers and suppliers as the small firm becomes more important to them, which in turn imparts legitimacy to the small firm (Ebben & Johnson, 2006). This legitimacy allows small firms to establish an organizational identity in the minds of their stakeholders (Clegg, Rhodes, & Kornberger, 2007), to develop other important organizational routines (Delmar & Shane, 2004), gain access to even more valuable resources (Lounsbury & Glynn, 2001), and to grow in spite of hostile environments (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2001). Therefore, based on these arguments, we expect minimal resource strategies, to be positively related to firm performance and competitive advantage (measured through growth) in small firms. This leads to the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 3b: The extent to which a firm relies on a minimal resource strategy will be positively related to firm expected growth.

METHODS Sample

We obtained our data come from a sample of 754 small firms that participated in a survey on competition sponsored by the National Federation of Independent Businesses and conducted by the Gallup Organization in late 2003 (NFIB, 2003). Participating firms ranged in size from one to 249 employees. The Gallup Organization used a random stratified sample design to compensate for the skew

toward firms with four or fewer employees (NFIB, 2003). When necessary, we corrected our data set for missing data as recommended by Roth (1994).

In the sample, two approaches to competing appear to be prevalent strategies among small-businesses: 1) Offering the highest possible quality; and 2) Offering better service (NFIB, 2003). Over 80 percent of small businesses that participated in a national survey on competition insist that these approaches represent a major portion of the way they attempt to compete (NFIB, 2003). This observation from the data appears logical and consistent with the expectations of prior research since providing the highest possible quality and better service is consistent with the survival strategy of building a loyal customer base (Liao & Chuang, 2004). Thus, there appears to be high face validity of the sample. A third major small business strategy was operating with minimal overhead. This observation is also consistent with the expectations of prior research (Stevenson, 1984; Timmons, 1999). Other, less common ways of competing, also included (in order of significance): maximum use of technology, targeting missed or poorly served customers, more choices and selection, unique marketing, lower prices, expansion or growth, a superior location, new or previously unavailable goods and services, alliances or cooperation with another firm or firms, and franchising (NFIB, 2003). Most of these less common strategies are consistent with an orientation toward firm growth. For this reason, as well as due to their low utilization among the small firms in the sample, we excluded them from the scope of the current study

MEASURES

Dependent variables. The dependent variables in this study are survival and expected growth. We measure Survival by the number of years a firm has been operating. Larger scale, older small businesses have higher survival rates over time than smaller, younger firms (Evans, 1987; Bates, 1995; Bates & Nucci, 1989), and only a fraction of firms from a given cohort of new firm startups survive (Aldrich & Martinez, 2001; Katz & Gartner, 1984). We measure Expected growth using a fivepoint Likert scale question asking Over the next three years, do you expect this business to: (1) grow significantly, (2) grow quite a bit, (3) grow some, (4) stay about the same, OR (5) get smaller. We reverse-coded the responses to associate a higher score with higher growth expectations.

Independent variables. The independent variables in this study are the types of strategies small businesses might pursue: highest possible quality, better service, and minimal overhead (NFIB, 2003). Each independent variable was measured with a single 9-point Likert scale question in which a value of 1 meant a given strategy play no part in the business competitive strategy and a value of 9 meant the strategy comprised its entire competitive strategy.

Controls. We control for industry effects on performance using NAICS categories at the two-digit level with dummy variables. Controlling for industry effects is important because general industry environments often influence the performance of firms (Dess et al., 1990; Rumelt, 1982, 1991). Without controlling for industry effects, researchers may obtain erroneous results, such as support for opposite relationships, or unsupportable relationships at best (Armstrong & Shimizu, 2007). We also controlled for firm size by incorporating the natural log of the number of employees. For tests of hypotheses in which the dependent variable is expected growth, we controlled for past sales growth. Past sales growth is measured by the percentage change in last two years sales for each firm using Likert scale values (5 = increased by 30%+; 4 = increased by 20 to 29%; 3 = Increased 10-19%; 4 = changed 10% either way; 1 = decreased by 10% or more).

Analysis. We tested our hypotheses using ordinary least squares regression. We included all control variables and the dependent variables in the first model. We then tested each hypothesis step-wise in individual models. Testing each of the small business strategies individually allows us to identify specific effect sizes and significances for each strategy and separate effects from non-effects (Armstrong & Shimizu, 2007). Further, the individual tests more accurately portray the activities of small businesses, since no firm likely attempts to implement all strategies at the same time (citation?).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the summary statistics and correlations for the study measures. The mean values for the independent variables show that the preference for small firm strategies was, in order, highest possible quality, better service, and minimal overhead. The mean values for highest possible quality (8.02) and better service (7.80) indicate that these approaches comprised close to 100% of a small firms competitive strategy. The mean value for minimal overhead strategies (5.87) shows that small firms incorporated this approach for more than 50% of their overall competitive strategies. These results suggest that small firm owners prefer simpler, less resource-intensive strategies to compete: doing what you already do more effectively and efficiently is simpler than creating a unique marketing strategy, expanding, or offering new goods or services.

TABLE 1 - SUMMARY STATISTICS AND CORRELATIONS

variables 1 Years Owned/Ope rated Business 2 Expect to Grow 3 Highest Possible 8.02 1.77 3.26 1.11 0.167 0.007 0.111 Mean 17.01 s.d 14.14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Quality 4 Better Service 5 Minimal Overhead 6 Past Sales Growth 7 Ln Firm Size 8 NAICS 10 0.119 0.117 9 NAICS 20 0.053 0.060 10 NAICS 30 0.122 0.068 2.14 1.27 2.82 1.26 5.87 2.52 0.066 0.148 0.158 0.073 0.006 0.028 0.019 0.018 0.122 0.056 0.032 0.022 0.120 0.047 11 NAICS 40 0.070 0.006 0.037 12 NAICS 50 0.103 13 NAICS 60 0.078 14 NAICS 70 0.087 15 NAICS 80 0.010 0.056 0.002 0.013 0.004 0.022 0.048 0.006 0.061 0.003 0.002 0.023 0.045 0.022 0.016 0.037 0.058 0.006 0.024 0.114 0.020 0.132 0.106 0.050 0.065 0.085 0.017 0.014 0.030 0.112 0.010 0.054 0.367 0.080 0.059 0.010 0.118 0.036 0.018 0.095 0.044 0.055 0.054 0.087 0.100 0.046 0.060 0.054 0.099 0.193 0.185 0.084 0.111 0.100 0.166 0.179 0.082 0.107 0.097 0.349 0.159 0.209 0.188 0.152 0.210 0.181 0.091 0.082 0.078 0.018 0.066 0.175 0.207 7.80 2.05 0.024 0.132 0.563

p < .01 for all correlations > |.095|, p < .05 for all correlations > |.073 |

Our first two hypotheses address the effects of the two most commonly used small firm strategies on firm survival and expected growth. In Hypothesis 1a, we predicted that the extent to which a small firm relies on a high quality differentiation strategy would be positively related to survival. The effect of high quality differentiation strategy was positive, as predicted, but not significant. Therefore, we fail to observe support for Hypothesis 1a.

In Hypothesis 1b, we predicted that the extent to which a small firm follows a high quality differentiation strategy would be positively related to expected growth. The effect of a high quality differentiation strategy on expected growth was positive and significant (p < .05). Therefore, we observe support for Hypothesis 1b.

In Hypothesis 2a, we predicted that a small firms use of a customer service differentiation strategy would be positively related to survival. As shown in Model 3 of Table 2, the effect of a customer service differentiation strategy on firm survival was positive as predicted, but not significant. Therefore, we fail to observe support for Hypothesis 2a.

In Hypothesis 2b, we argue that a small firms customer service differentiation strategy would be positively related to expected growth. As Model 3 of Table 3 shows, the effect of better service on firm expected growth is positive and significant (p < .05). Therefore, we observe support for Hypothesis 2b.

In Hypotheses 3a, we argued that a small firms use of minimal overhead would be negatively related to firm survival. We observe that the effects of minimal overhead on small firm survival were negative and significant (p < .05). Therefore, we observe support for Hypothesis 3a.

In Hypotheses 3b, we predicted that a small firms use of minimal overhead would be positively related to expected growth. As shown in Model 4 of Table 3, the effect of a smallfirms use of minimal overhead on expected growth was positive and significant (p < .05). Therefore, we observe support for Hypothesis 3b.

TABLE 2 - LINEAR REGRESSION RESULTS FOR FIRM SURVIVAL

Models Hypothesis Variables Constant Firm size NAICS 10 NAICS 20 NAICS 30 NAICS 40 NAICS 50 NAICS 60 NAICS 70 NAICS 80 Past Sales Growth 17.646 *** 0.074 *** 13.223 ** 5.149 7.168 * 4.241 0.653 -1.096 -1.829 2.851 -1.689 *** 15.939 *** 0.074 *** 13.347 ** 5.237 7.206 * 4.329 0.725 -1.113 -1.778 2.895 -1.713 *** 15.194 *** 0.073 *** 13.8 ** 5.399 7.238 * 4.36 0.769 -0.942 -1.701 2.929 -1.721 19.780 *** 0.071 *** 13.805 ** 5.483 8.008 * 4.574 0.945 -0.712 -1.349 3.373 -1.687 *** 1 2 H1a 3 H2a 4 H3a

Strategy Highest Possible Quality Better Service Minimal Overhead 0.31 -0.424 * 0.214

F AdjR2 DAdjR2

8.188 *** 0.087

7.493 *** 0.087 0

7.598 *** 0.088 0.001

7.899 *** 0.092 0.005 **

p < .10, *p < 0.05, **p < .01, *** P < .001 n = 754

TABLE 3 - LINEAR REGRESSION RESULTS FOR FIRM EXPECTED GROWTH

Models Hypothesis Variables Constant Firm size NAICS 10 NAICS 20 NAICS 30 NAICS 40 NAICS 50 NAICS 60 NAICS 70 NAICS 80 Past Sales Growth

2 H1a

3 H2a

4 H3a

2.531 *** 0.048 -1.008 ** -0.506 0.007 -0.275 -0.227 -0.270 -0.332 -0.225 0.327 ***

2.160 *** 0.049 -0.981 ** -0.487 0.014 -0.257 -0.212 -0.274 -0.332 -0.215 0.322 ***

2.169 *** 0.044 -0.923 ** -0.468 0.018 -0.257 -0.21 -0.247 -0.311 -0.214 0.326 ***

2.530 *** 0.057 -1.05 ** -0.534 -0.061 -0.302 -0.249 -0.301 -0.372 -0.263 0.326 ***

Strategy Highest Possible Quality Better Service Minimal Overhead 0.046 * 0.033 * 0.046 *

F AdjR2 DAdjR2

15.415 *** 0.161

14.546 *** 0.165 0.004

14.733 *** 0.167 0.006 *

14.556 *** 0.165 0.004

p < .10, *p < 0.05, **p < .01, *** P < .001 n = 754

DISCUSSION

Implications

We opened this paper with the assertion that opportunities may have been missed in the prior research on the strategies of entrepreneurial and small ventures to: 1) Differentiate forms of strategy among different types of small firms; and 2) To help explore the relevance and applicability of strategic management theories to the context of small firms. The objective of our study was to explore the types of strategies that small firms may theoretically pursue and then to test how these strategies may affect their survival and growth. In these regards, we theorized differences between the strategies of small and large firms, and explored some of the most theoretically and practically relevant small firm strategies (high quality differentiation, customer service differentiation, and minimal resources).

We then developed hypotheses for the relationship between these small business strategies and firm survival and growth, arguing that the differentiation strategies should be theoretically positively related to both small firm survival and growth, and that minimal resource strategies would be negatively related to survival, but positively related to growth. We failed to observe support for our arguments that the strategies to differentiate on high quality or customer service would be positively related to firm survival. An interesting implication of these observations is that the

dominant survival strategies pursued by 80% of the small businesses in our sample, dont lead to survival. We did, however observe support for our arguments that the strategies to differentiate on high quality or customer service would be positively related to firm growth. Finally, we did observe support for our arguments that minimal resource strategies would be negatively related to firm survival and positively related to firm growth. These observations are consistent with our expectations and raise some interesting issues for future research on the implications of bootstrapping.

So, in a sense, our observations may indicate that the essence of small firm strategy is to pursue a course of action that causes the firm to cease being small (Aldrich & Auster, 1986; Covin & Slevin, 1989; Merz et al., 1994). Our results indicate, however, that small firms that pursue a path of growth do so simultaneously increase the likelihood that they will fail. The correlation between expected growth and firm survival is strongly negative and significant (p < .01). This finding supports the assertion that small firms suffer from the liabilities of age (Stinchcombe, 1965) and size (Aldrich & Auster, 1986) that limit the effectiveness of the strategies they employ in competition. In addition to limiting the effectiveness of strategies, this finding also supports that assertion that small firms are limited in their choices of strategy due to size, age, or industry (Brush & Chaganti, 1999).

Further, our finding that the effects of use of minimal overhead strategies were negatively and significantly related to small firm survival, may indicate that a small firms efforts to find, acquire and combine resources to create a unique identity can place limits on the scale and scope of the small firms operations and therefore limit its strategic options (Morris, 2001). The commitment of resources to pursue differentiation strategies, reach new markets, or offer new goods and services may reduce the ability of small firms to survive external shocks and adapt to changing market conditions.

Our results, coupled with the results of the NFIB study (2003), also provide support for our assertion that all small firms do pursue some form of strategy. Small firms recognize that they all face some form of competition and take strategic actions to differentiate themselves to survive and grow. The mean values for the independent variables of highest possible quality (8.02 on a scale of 1 to 9) and better service (7.80 on a scale of 1 to 9) were far greater than the mean value for minimal resource strategies (5.87), indicating most small firms relied on these approaches for close to 100% of their overall competitive strategies. This finding suggests that small firm owners are capable of observing and learning from their experiences in competition with each other and in their industries.

What do the results say about Carland et als (1984) seminal argument about small business ventures versus entrepreneurial ventures? First, we conclude that all businesses follow some form of strategy in their operations. Most of the businesses in this study are indeed independently owned and operated, not dominant in their fields (Carland et al, 1984), but many also do attempt to engage in new marketing or innovative practices. The choice to pursue innovative, growth-oriented practices, however, presents new challenges to small businesses that can lead to outright failure of the venture. For this reason we believe that researchers and policy makers should strive to make a finer distinction between small businesses that are not growth oriented and those that risk their survival in the pursuit of growth.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future studies of small firm strategy. First, our data set, while originating from a reputable data gathering agency, was crosssectional in nature. This prevented us from making causeand-effect connections between small firm strategies, survival, and expected growth. The data set also relied on self-reporting responses from small business owners, which could cause this study to have a common method variance (Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Mowday & Sutton, 1993). This could be particularly troublesome in making the connection between preferences and reliance on different small firm strategies and expectations for growth. A small business owner may, for example, optimistically

believe that his or her use of a variety of strategies will lead to greater future growth, when in fact he or she may be risking the very survival of the firm.

We used expected growth rather than past growth because we wanted to capture the effects of small firm strategies on future growth, rather than past growth. Using past growth as the dependent variable would be illogical for determining the temporal precedent of strategy choices on future firm performance. In other words, we wanted to make an association between small firm owners preferences for strategies with the owners performance expectations for the firm. We capture the effect of past performance for both firm survival and expected growth by using it as a control variable. Expected growth has been used as the dependent variable in empirical studies preceding this one (e.g., Beccheti & Trovato, 2002; Dunne, Roberts, & Samuelson, 1989; Heshmati, 2001).

CONCLUSION

The objective of our study was to explore the types of strategies that small firms may theoretically pursue and then to test how these strategies may affect their survival and growth. Through this study, we contribute by (1) examining the extent to which small firms may engage in strategic behaviors to determine the applicability of strategic management theories to the contexts; (2) improving our understanding of the effectiveness and performance implications of different strategies for the context,

and, (3) enriching our understanding of the strategic management practices that dominate economic activity. In conclusion, we found that the essence of small firm strategy may be to pursue a course of action that causes the firm to grow (Aldrich & Auster, 1986; Covin & Slevin, 1989; Merz et al., 1994). Small firms that choose this path, however, risk their very survival if they pursue the most common strategies of differentiating through high quality and customer service, or minimal use of resources. Therefore, the best strategy for small firm survival may be to stay small.

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. 2001. Learning from successful local private firms in China: Establishing legitimacy. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4): 72-83. Aldrich, H. E., & Auster, E. R. 1986. Even dwarfs started small: Liabilities of age and size and their strategic implications. Research in Organizational Behavior, 8: 165198.

Aldrich, H. E., & Martinez, M. A. 2001. Many are called, but few are chosen: An evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 25(4): 41-56. Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. 2000. Manufacturing advantage. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press. Armstrong, C. E., & Shimizu, K. 2007. A review of approaches to empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 33: 959-986. Barney, J. B. 1986. Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32: 1231-1241. Barney, J. B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17: 99-120. Bates, T. 1995. A comparison of franchise and independent small business survival rates. Small Business Economics, 7: 377-388. Bates, T., & Nucci, A. R. 1989. An analysis of small business size and rate of discontinuance. Journal of Small Business Management, 27(4): 1-8.

Batt, R. 2002. Managing customer services: Human resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth. Academy of Management Journal, 45: 587-597. Becchetti, L., & Trovato, G. 2002. The determinants of growth for small and medium sized firms: The role of the availability of external finance. Small Business Economics, 19: 291-306. Bowen, D. E., & Waldman, D. A. 1999. Customer-driven employee performance. In D. A. Ilgen, & E. D. Pulakos (Eds.), The changing nature of performance: 154-191. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Brush, C. G., and Chaganti, R. 1999. Businesses without glamour? An analysis of resources on performance by size and age in small service and retail firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 14(3), 233-257. Campbell, D., & Fiske, D. 1959. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitraitmultimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56: 81-105. Carland, J. W., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. R., & Carland, J. A. C. 1984. Differentiating entrepreneurs

from small business owners: A conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 9: 354-359. Carter, R. B., & Van Auken, H. 2005. Bootstrap financing and owners' perceptions of their business constraints and opportunities. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 17(2): 129-144. Carter, S., & Ram, M. 2003. Reassessing portfolio entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 21: 371-380. Churchill, N. C., & Lewis, V. L. 1983. The five stages of small business growth. Harvard Business Review, 61(3): 30-39. Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. 1989. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10: 75-87. Delery, J., & Doty, H. 1996. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39: 802-835.

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. 2004. Legitimating first: Organizing activities and the survival of new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3): 385-410. Dess, G. G., Ireland, R. D., & Hitt, M. A. 1990. Industry effects and strategic management research. Journal of Management, 16: 7-27. Dietz, J., Pugh, S. D., & Wiley, J. W. 2004. Service climate effects on customer attitudes: An examination of boundary conditions. Academy of Management Journal, 47: 81-92. Dyer, J., & Singh, H. 1998. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23: 660679. Evans, D. S. 1987. The relationship between firm growth, size, and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35: 567-581. Gross, A. 1967. Meeting the competition of giants. Harvard Business Review, 45(3): 172-184. Gulati, R. 1998. Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19: 293411. Heshmati, A. 2001. On the growth of micro and small firms: Evidence from Sweden. Small

Business Economics, 17: 213-228. Hoopes, D. G., Madsen, T. L., & Walker, G. 2003. Why is there a resource-based view? Toward a theory of competitive heterogeneity. Strategic Management Journal, 24: 889-902. Hoyer, W. D., & Brown, S. P. 1990. Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common, repeat purchase product. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2): 141-148. Huselid, M. 1995. The impact of human resources management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 635-672. Katz, J. A., & Gartner, W. B. 1988. Properties of emerging organizations. Academy of Management Review, 13: 429-441. Liao, H., & Chuang, A. 2004. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 47: 41-58. Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. 2001. Cultural entrepreneurship: Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6-7): 545-564.

McGrath, R. G. 1999. Falling forward: Real options reasoning and entrepreneurial failure. Academy of Management Review, 24: 13-30. Merz, G. R., Weber, P. B., & Laetz, V. B. 1994. Linking small business management with entrepreneurial growth. Journal of Small Business Management(October): 48-60. Morris, M. H., Koak, A., & zer, A. 2007. Coopetition as a small business strategy: Implications for performance. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 18(1): 3555. Mowday, R., & Sutton, R. 1993. Organizational behavior: Linking individuals and groups to organizational contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 44: 195-229. NFIB, 2003. National Small Business Poll on Competition. NFIB Research Foundation, 3(8). www.nfib.com/research. Nooteboom, B. 1993. Firm size effects on transaction costs. Small Business Economics, 5(4): 283-295. Oosterbeek, H., & Van Praag, C. M. 1995. Firm-size wage differentials in the Netherlands. Small Business Economics, 7: 173-182.

Parker, S. C. 2004. The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pelham, A. M. 1999. Influence of environment, strategy, and market orientation on performance in small manufacturing firms. Journal of Business Research, 45(1): 33-46. Penrose, E. 1959. The Theory of The Growth of The Firm. Peteraf, M. A. 1993. The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14: 179-191. Porter, M. E. 1985. Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press. Reider, R. 2008. Effective operations and controls for the privately held business. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Roth, P. 1994. Missing data: A conceptual review for applied psychologists. Personnel Psychology, 47: 537-560. Solomon, S. 1986. Small business USA. New York: Crown Publishers.

Solomon, M. R., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J. A., & Gutman, E. G. 1985. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 49(winter): 99-111. Starr, J. A., & MacMillan, I. C. 1990. Resource cooptation via social contracting: Resource acquisition strategies for new ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 11(Summer special issue): 79-92. Stinchcombe, Arthur L. 1965. Social Structure and Organizations, in Handbook of Organizations, March, J. G. (Ed.). Chicago: Rand McNally. Storey, D. 1994. Understanding the small business sector. New York: Routledge. Tatge, M. 2003. Bet on the small fry, Forbes, Vol. 172(4): 122-123. Timmons, J. A. 1999. New venture creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st century (5th ed.). Boston: Irwin. Troske, K. R. 1999. Evidence on the employer size-wage premium from workerestablishment matched data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81: 15-26. U.S. SBA. 2007. What is small business: http://www.sba.gov/services/contractingopportunities/sizestandardstopics/size /index.html

Van Praag, C. M. 2003. Business survival and success of young small business owners. Small Business Economics, 21: 1-17. Van Praag, C. M., & Versloot, P. H. 2007. What is the value of entrepreneurship? A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29: 351-382. Welsh, J. A., & White, J. F. 1981. A small business is not a little big business. Harvard Business Review, 59(4): 18-32. Wernerfelt, B. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5: 171180. Wiklund, J. 1998. Small firm growth and performance: Entrepreneurship and beyond. Jonkoping University, Jonkoping International Business School. Winborg, J., & Landstrom, H. 2001. Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: Examining small business managers' resource acquisition. Journal of Business Venturing, 16: 235254.

Winter-Ebmer, R., & Zweimuller, J. 1999. Firm-size wage differentials in Switzerland: Evidence from job-changers. The American Economic Review, 89(2): 89-93. Wunnava, P. V., & Ewing, B. T. 2000. Union-nonunion gender wage and benefit differentials across establishment sizes. Small Business Economics, 15: 47-57.

You might also like

- The Genius Is Inside.: A High Performance Step-By-Step Strategy Guide for Small and Medium Size Companies.From EverandThe Genius Is Inside.: A High Performance Step-By-Step Strategy Guide for Small and Medium Size Companies.No ratings yet

- Sample Qualitative PaperDocument70 pagesSample Qualitative PaperFaye DimabuyuNo ratings yet

- Critical Competitive Strategies Every Entrepreneur Should ConsiderDocument11 pagesCritical Competitive Strategies Every Entrepreneur Should ConsiderrasanavaneethanNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On HRM in Small and Medium Enterprises......Document28 pagesTerm Paper On HRM in Small and Medium Enterprises......Abbas Ansari50% (8)

- Small Firm Strategy in Turbulent Times: Thomas M. Box, Pittsburg State UniversityDocument8 pagesSmall Firm Strategy in Turbulent Times: Thomas M. Box, Pittsburg State UniversityAnkit AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Innovation Case StudyDocument7 pagesInnovation Case Studybilhar keruboNo ratings yet

- Business Owners 313.htmlDocument5 pagesBusiness Owners 313.htmlAngelica AngelesNo ratings yet

- Velocity: Combining Lean, Six Sigma and the Theory of Constraints to Achieve Breakthrough Performance - A Business NovelFrom EverandVelocity: Combining Lean, Six Sigma and the Theory of Constraints to Achieve Breakthrough Performance - A Business NovelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- If You're in a Dogfight, Become a Cat!: Strategies for Long-Term GrowthFrom EverandIf You're in a Dogfight, Become a Cat!: Strategies for Long-Term GrowthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 1+1=3 The New Math of Business Strategy: How to Unlock Exponential Growth through Competitive CollaborationFrom Everand1+1=3 The New Math of Business Strategy: How to Unlock Exponential Growth through Competitive CollaborationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Asa Romeo Asa Analysis On The Factors That Determine Sustainable Growth of Small Firms in NamibiaDocument7 pagesAsa Romeo Asa Analysis On The Factors That Determine Sustainable Growth of Small Firms in NamibiaOlaru LorenaNo ratings yet

- MarketingDocument10 pagesMarketingJoseph MwathiNo ratings yet

- Capital Strategies for Micro-Businesses: Micro-Business Mastery, #1From EverandCapital Strategies for Micro-Businesses: Micro-Business Mastery, #1No ratings yet

- Small Business Survival and Growth (#457334) - 530738Document13 pagesSmall Business Survival and Growth (#457334) - 530738Umar FarouqNo ratings yet

- Final ThesisDocument66 pagesFinal ThesisHiromi Ann ZoletaNo ratings yet

- Cut Costs, Grow Stronger : A Strategic Approach to What to Cut and What to KeepFrom EverandCut Costs, Grow Stronger : A Strategic Approach to What to Cut and What to KeepRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Gray - Entrepreneuship Resistance To Change and Growth in Small Firms - GrayDocument12 pagesGray - Entrepreneuship Resistance To Change and Growth in Small Firms - Graypaul4you24No ratings yet

- Lessons from Private Equity Any Company Can UseFrom EverandLessons from Private Equity Any Company Can UseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- 2000georgellisjoyceandwoodsentrepreneurial ActionDocument11 pages2000georgellisjoyceandwoodsentrepreneurial Actiondawit turaNo ratings yet

- EA203029 Hira Mahbooba Churchill ESBMDocument15 pagesEA203029 Hira Mahbooba Churchill ESBMShurovi ShovaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Enterpreneur and Firm Characteristics On The Business Success of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in North Central, NigeriaDocument8 pagesEffect of Enterpreneur and Firm Characteristics On The Business Success of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in North Central, NigeriaThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Management and Leadership Skills that Affect Small Business Survival: A Resource Guide for Small Businesses EverywhereFrom EverandManagement and Leadership Skills that Affect Small Business Survival: A Resource Guide for Small Businesses EverywhereNo ratings yet

- Getting Bigger by Growing Smaller (Review and Analysis of Shulman's Book)From EverandGetting Bigger by Growing Smaller (Review and Analysis of Shulman's Book)No ratings yet

- Run Your Business Like a Fortune 100: 7 Principles for Boosting ProfitsFrom EverandRun Your Business Like a Fortune 100: 7 Principles for Boosting ProfitsNo ratings yet

- DORCAS BIRMAN CHAPTER ONE, TWO AND THREE (Edited)Document61 pagesDORCAS BIRMAN CHAPTER ONE, TWO AND THREE (Edited)SIVREX24No ratings yet

- Mekidelawit Tamrat MBAO9550.14B SMDocument8 pagesMekidelawit Tamrat MBAO9550.14B SMHiwot GebreEgziabherNo ratings yet

- Cooney Entrepreneurship Skills HGFDocument23 pagesCooney Entrepreneurship Skills HGFSurya PrasannaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document25 pagesChapter 3kirubel solomonNo ratings yet

- THESIS (CHAPTERS) ABOUT SMEs IN SAN JUAN, BATANGASDocument26 pagesTHESIS (CHAPTERS) ABOUT SMEs IN SAN JUAN, BATANGASJaqueline Mae Amaquin100% (1)

- Mba Project - ProposalDocument6 pagesMba Project - ProposalJijulal NairNo ratings yet

- Building Lean Companies: How to Keep Companies Profitable as They GrowFrom EverandBuilding Lean Companies: How to Keep Companies Profitable as They GrowNo ratings yet

- Filesem 1542013693Document40 pagesFilesem 1542013693benpweetyNo ratings yet

- CAF - Volume 40 - Issue عدد خاص (مؤتمر الکلية 2020 - الجزء الثاني) - Pages 1-31Document29 pagesCAF - Volume 40 - Issue عدد خاص (مؤتمر الکلية 2020 - الجزء الثاني) - Pages 1-31Hassan ElmiNo ratings yet

- Repeatability (Review and Analysis of Zook and Allen's Book)From EverandRepeatability (Review and Analysis of Zook and Allen's Book)No ratings yet

- No-Excuses Innovation: Strategies for Small- and Medium-Sized Mature EnterprisesFrom EverandNo-Excuses Innovation: Strategies for Small- and Medium-Sized Mature EnterprisesNo ratings yet

- The Capital Budgeting Decisions of Small BusinessesDocument19 pagesThe Capital Budgeting Decisions of Small BusinessesPrateek Tripathi100% (1)

- Midlands State University: Faculty of CommerceDocument13 pagesMidlands State University: Faculty of CommerceRudolph MugwagwaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Approaches in Australian Smes: Deliberate or Emergent?Document26 pagesStrategic Approaches in Australian Smes: Deliberate or Emergent?Moncef ChorfiNo ratings yet

- Mcfarland2012 PDFDocument12 pagesMcfarland2012 PDFValter EliasNo ratings yet

- Business Research 1 1Document15 pagesBusiness Research 1 1Ei-Ei EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Venture Catalyst (Review and Analysis of Laurie's Book)From EverandVenture Catalyst (Review and Analysis of Laurie's Book)No ratings yet

- Ruthless Execution (Review and Analysis of Hartman's Book)From EverandRuthless Execution (Review and Analysis of Hartman's Book)No ratings yet

- The Capital Budgeting Decisions of Small BusinessesDocument21 pagesThe Capital Budgeting Decisions of Small BusinessesKumar KrisshNo ratings yet

- Usama ShafiqueDocument14 pagesUsama ShafiqueMuhammad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Module CH 3 5Document67 pagesEntrepreneurship Module CH 3 5Birhanu AdmasuNo ratings yet

- The Age of Agile: How Smart Companies Are Transforming the Way Work Gets DoneFrom EverandThe Age of Agile: How Smart Companies Are Transforming the Way Work Gets DoneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- CHAPTER 1 3 Sample For StudentsDocument26 pagesCHAPTER 1 3 Sample For Studentsmaryjoybasaysay57No ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument20 pagesChapter IIvy CoronelNo ratings yet

- Assignment For OlusojiDocument20 pagesAssignment For OlusojibelloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document18 pagesChapter 3Bereket YohanisNo ratings yet

- The SWOT Analysis: A key tool for developing your business strategyFrom EverandThe SWOT Analysis: A key tool for developing your business strategyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Does Managerial Capital Also Matter Among Micro and Small Firms in Developing Countries?Document39 pagesDoes Managerial Capital Also Matter Among Micro and Small Firms in Developing Countries?Martín KloseNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Lack of Strategic Planning in SMEs - The ImportanceDocument17 pagesExplaining The Lack of Strategic Planning in SMEs - The ImportancerexNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 # 4Document41 pagesChapter 3 # 4sami damtewNo ratings yet

- Assignment Number 3 (100 Points) Operationalization of ConstructsDocument7 pagesAssignment Number 3 (100 Points) Operationalization of ConstructsJan Morihei SevillaNo ratings yet

- Assignments TOK 2 LanguageDocument4 pagesAssignments TOK 2 LanguageAsullivan424No ratings yet

- Segmenting and TargetingDocument22 pagesSegmenting and TargetingMalik MohamedNo ratings yet

- Cupola KFCDocument14 pagesCupola KFCBushra FaranNo ratings yet

- The Champion Legal Ads 10-15-20Document46 pagesThe Champion Legal Ads 10-15-20Donna S. SeayNo ratings yet

- Lifebuoy Product Life Cycle JAYASUDHARSANDocument35 pagesLifebuoy Product Life Cycle JAYASUDHARSANanon_130845589No ratings yet

- Questionnaire For Rural ConsumerDocument7 pagesQuestionnaire For Rural ConsumerAnjali AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Unit 4-Lis 1Document2 pagesUnit 4-Lis 1Thúy ViNo ratings yet

- Comparison of E-Wallet AdvertisementDocument11 pagesComparison of E-Wallet AdvertisementAdib NazhanNo ratings yet

- Product Launching StrategiesDocument7 pagesProduct Launching Strategiesbabunaidu2006No ratings yet

- Strategy & Customer Led Business: University of BrightonDocument4 pagesStrategy & Customer Led Business: University of BrightoncharbelNo ratings yet

- Hydrox Trademark DecisionDocument31 pagesHydrox Trademark DecisionMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Advertising AppealsDocument87 pagesDifferent Types of Advertising AppealsSjsvkjsh Ssdsf0% (1)

- Enough: Breaking Free From The World of ExcessDocument7 pagesEnough: Breaking Free From The World of ExcessMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Business Com MM Final LL LLLLLDocument16 pagesBusiness Com MM Final LL LLLLLSamihaSaanNo ratings yet

- All KYCDocument4 pagesAll KYCPatwary MämúñNo ratings yet

- Assignment Topics - III BCOM CADocument10 pagesAssignment Topics - III BCOM CAT DineshNo ratings yet

- Principles of Marketing ModuleDocument75 pagesPrinciples of Marketing ModuleJecelle BalbontinNo ratings yet

- Vogue Girl Korea 2013Document28 pagesVogue Girl Korea 2013daniellemuntyan100% (1)

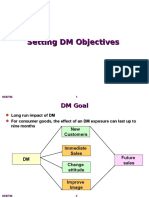

- DM Obj Goals Dagmar ModelsDocument30 pagesDM Obj Goals Dagmar ModelslakshayNo ratings yet

- The Information Overload Controversy: An Alternative ViewpointDocument12 pagesThe Information Overload Controversy: An Alternative ViewpointSarah CopelandNo ratings yet

- Byte Mobile Mobile Analytics Report Feb2012Document6 pagesByte Mobile Mobile Analytics Report Feb2012Arda KutsalNo ratings yet

- Hubspot: Inbound Marketing and Web 2.0Document2 pagesHubspot: Inbound Marketing and Web 2.0Muhammad Wildan FadlillahNo ratings yet

- Maketing Plan Vissan Canned FoodDocument34 pagesMaketing Plan Vissan Canned FoodSandra Hwang100% (3)

- Attracting Investor Attention Through AdvertisingDocument46 pagesAttracting Investor Attention Through Advertisingroblee1No ratings yet

- Retail Store ImageDocument19 pagesRetail Store Imagehmaryus0% (1)

- Marico IndiustriesDocument58 pagesMarico Indiustriespranjal100% (1)

- The Ultimate No BS Guide To Entrepreneurial Success - BookDocument208 pagesThe Ultimate No BS Guide To Entrepreneurial Success - BookLobito Solitario100% (11)

- Chapter-13: Retailing: Course: Marketing Channels (MKT 450) Faculty: Abdullah Al Faruq (Afq)Document5 pagesChapter-13: Retailing: Course: Marketing Channels (MKT 450) Faculty: Abdullah Al Faruq (Afq)KaziRafiNo ratings yet

- Service Marketing Management Wouter de Vries Jr.Document43 pagesService Marketing Management Wouter de Vries Jr.Anissa Negra AkroutNo ratings yet

- Two Entries StoryDocument4 pagesTwo Entries Storyapi-428628528No ratings yet