Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Money Supply and Money Demand: Chapter Eighteen

Uploaded by

Sharad Ranjan TyagiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Money Supply and Money Demand: Chapter Eighteen

Uploaded by

Sharad Ranjan TyagiCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter Eighteen 1

A PowerPoint

Tutorial

to Accompany macroeconomics, 5th ed.

N. Gregory Mankiw

Mannig J. Simidian

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Money Supply and Money Demand

Chapter Eighteen 2

Chapter Eighteen 3

M = C + D

Money Supply

Currency

Demand Deposits

In this chapter, well see that the money supply is determined not only

by the Federal Reserve, but also by the behavior of households

(which hold money) and banks (where money is held).

Chapter Eighteen 4

The deposits that banks have received but have not lent out are called

reserves. Consider the case where all deposits are held as reserves:

banks accept deposits, place the money in reserve, and leave the

money there until the depositor makes a withdrawal or writes a check

against the balance.

In a 100% reserve banking system, all deposits are held in reserve and

thus the banking system does not affect the supply of money.

Chapter Eighteen 5

As long as the amount of new deposits approximately equals the

amount of withdrawals, a bank need not keep all its deposits in

reserves. Note: a reserve-deposit ratio is the fraction of deposits

kept in reserve. Excess reserves are reserves above the reserve

requirement.

Fractional-reserve banking, a system under which banks keep

only a fraction of their deposits in reserve. In a system of

fractional reserve banking, banks create money.

Chapter Eighteen 6

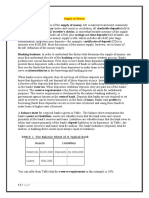

Firstbank

Balance Sheet

Secondbank

Balance Sheet

Thirdbank

Balance Sheet

Assets Liabilities Assets Liabilities Assets Liabilities

Reserves $200 Deposits $1,000

Loans $800

Reserves $128 Deposits $640

Loans $512

Reserves $160 Deposits $800

Loans $640

Assume each bank maintains a reserve-deposit ratio (rr) of 20% and that the initial deposit is $1000.

Mathematically, the amount of money the original $1000 deposit creates is:

Original Deposit =$1000

Firstbank Lending = (1-rr) $1000

Secondbank Lending = (1-rr)

2

$1000

Thirdbank Lending = (1-rr)

3

$1000

Fourthbank Lending = (1-rr)

4

$1000

Total Money Supply = [1 + (1-rr) + (1-rr)

2

+ (1-rr)

3

+ ] $1000

= (1/rr) $1000

= (1/.2) $1000

= $5000

Money and Liquidity Creation

.

.

.

The process of transferring funds

from savers to borrowers is called

financial intermediation.

Chapter Eighteen 7

Three exogenous variables:

The monetary base B is the total number of dollars held by the

public as currency C and by the banks as reserves R.

The reserve-deposit ratio rr is the fraction of deposits D that banks

hold in reserve R.

The currency-deposit ratio cr is the amount of currency C

people hold as a fraction of their holdings of demand deposits D.

Definitions of the money supply and the monetary base:

M=C+D

B =C+R

Solving for M as a function of the 3 exogenous variables:

M/B = C/D + 1

C/D + R/D

Making the substitutions for the fractions above, we obtain:

cr + 1

cr + rr

B

M =

Lets call this the money multiplier, m.

Chapter Eighteen 8

M = m B

Money Supply

Money multiplier

Monetary Base

Because the monetary base has a multiplied effect on the money supply,

the monetary base is sometimes called high-powered money.

Chapter Eighteen 9

Lets go back to our three exogenous variables to see how

their changes cause the money supply to change:

The money supply M is proportional to the monetary base B.

So, an increase in the monetary base increases the money supply

by the same percentage.

The lower the reserve-deposit ratio rr (R/D), the more loans

banks make, and the more money banks create from every dollar

of reserves.

The lower the currency-deposit ratio cr (C/D) , the fewer

dollars of the monetary base the public holds as currency, the

more base dollars banks hold in reserves, and the more money

banks can create. Thus a decrease in the currency-deposit ratio

raises the money multiplier and the money supply.

Chapter Eighteen 10

How does the Fed control the money supply?

1) Open Market Operations

(buying and selling U.S. Treasury bonds).

2) D Reserve Requirements

(never really used).

3) D Discount rate at which member banks

(not meeting the reserve requirements) can

borrow from the Fed.

Chapter Eighteen 11

According to the Quantity Theory of Money, (M/P)

d

= kY, where k is a constant

measuring how much people want to hold for every dollar of income.

Later we adopted a more realistic money demand function where the demand for

real money balances depends on i and Y: (M/P)

d

= L(i, Y).

They emphasize the role of money as a store of value; people hold money as a

part of their portfolio of assets. Key insight: money offers a different risk and

return than other assets. Money offers a safe nominal return, while other

investments may fall in both real and nominal terms.

They emphasize the role of money as a medium of exchange; they acknowledge

that money is a dominated asset and stress that people hold money, unlike other

assets, to make purchases. They explain why people hold narrow measures of

money like currency or checking accounts.

Classical Theory of Money Demand

Keynesian Theory of Money Demand

Portfolio Theories of Money Demand

Transactions Theories of Money Demand

Lets examine one transaction theory called the Baumol-Tobin model.

Chapter Eighteen 12

Total Cost = Forgone Interest + Cost of Trips

Total Cost = iY/(2N) + FN

interest

income

# of trips

# of trips

travel

cost

There is only one value of N that minimizes total cost. The optimal

value of N is denoted N*.

N* = iY/2F

Average Money Holding is = Y/2(N*)

= YF/2i

Chapter Eighteen 13

N*

Cost of trips to bank (FN)

Forgone interest (iY/(2N))

Total cost = iY/(2N) + FN

One implication of the Baumol-Tobin model is that any change

in the fixed cost of going to the bank F alters the money demand

function-- that is, it it changes the quantity of money demanded for a

given interest rate and income.

Number of trips to bank

Cost

The cost of money holding: forgone interest, the cost of trips to the

bank, and total cost depend on the number of trips N. One value of

N denoted N*, minimizes total cost.

Chapter Eighteen 14

The Baumol-Tobin models square root formula implies that the

income elasticity of money demand is : a 10% increase in income

should lead to a 5% increase in the demand for real balances.

In reality, however, most people have income elasticities that are

larger than and interest elasticities smaller than .

But, if you imagine a world in which there are two kinds of people:

Baumol-Tobins with elasticities of . The others have a fixed N, so

they have an income elasticity of 1 and an interest elasticity of 0.

In this case, the overall demand looks like a weighted average of the

demands for both groups. Income elasticity will be between and 1,

and the interest elasticity will be between and 0 just as the

empirical evidence shows.

Chapter Eighteen 15

Near money consists of assets that have acquired the liquidity of money

(e.g. checks that can be written against mutual fund accounts).

Near money causes instability in money demand and can give faulty

signals about aggregate demand.

One response to this problem is to use a broad definition of money that

includes near money however, it is hard to choose what kinds of assets

should grouped together.

Chapter Eighteen 16

Reserves

100-percent-reserve banking

Balance sheet

Fractional-reserve banking

Financial intermediation

Monetary base

Reserve-deposit ratio

Currency-deposit ratio

Money multiplier

High-powered money

Open-market operations

Reserve requirements

Discount rate

Excess reserves

Portfolio theories

Dominated asset

Transactions theories

Baumol-Tobin model

Near money

You might also like

- Econ Notes 3Document13 pagesEcon Notes 3Engineers UniqueNo ratings yet

- NBS Bank Statement Dec 2022Document2 pagesNBS Bank Statement Dec 2022Eric CartmanNo ratings yet

- Financial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionFrom EverandFinancial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- The Supply of MoneyDocument6 pagesThe Supply of MoneyRobertKimtaiNo ratings yet

- Keynes Demand For MoneyDocument9 pagesKeynes Demand For MoneyAppan Kandala Vasudevachary100% (1)

- Deloitte Robo SafeDocument5 pagesDeloitte Robo SafeLoro PiancaNo ratings yet

- Keynes Demand For MoneyDocument7 pagesKeynes Demand For MoneyAppan Kandala Vasudevachary100% (3)

- Chap29 PremiumDocument34 pagesChap29 PremiumNGOC HOANG BICHNo ratings yet

- Sbi and HDFC BankDocument51 pagesSbi and HDFC BankSumit ChakravortyNo ratings yet

- MACROECONOMICS, 7th. Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Mannig J. SimidianDocument21 pagesMACROECONOMICS, 7th. Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Mannig J. SimidianAnsoy AvesNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 2 Supply and Demand For MoneyDocument31 pagesChapter - 2 Supply and Demand For MoneyDutch EthioNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics: Money Supply and Money DemandDocument7 pagesMacroeconomics: Money Supply and Money DemandSharhie RahmaNo ratings yet

- Money Is Defined As Any Asset That People Are Willing To Accept in Exchange For Goods andDocument4 pagesMoney Is Defined As Any Asset That People Are Willing To Accept in Exchange For Goods andVũ Hồng PhươngNo ratings yet

- Money and BankingDocument10 pagesMoney and BankingMaruf AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Money MarketDocument20 pagesThe Money MarketNick GrzebienikNo ratings yet

- Money SupplyDocument8 pagesMoney Supplyladankur23No ratings yet

- Money Supply NotesDocument10 pagesMoney Supply Notesmary wanjiruNo ratings yet

- Concept of Money SupplyDocument7 pagesConcept of Money SupplyMD. IBRAHIM KHOLILULLAHNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Financial Market: 1 Reference: Macroeconomics, Blanchard 5/e UpdatedDocument42 pagesChapter 4 Financial Market: 1 Reference: Macroeconomics, Blanchard 5/e UpdatedrnitchNo ratings yet

- Workbook PDFDocument60 pagesWorkbook PDFcaritoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Financial Markets: 4-1 The Demand For MoneyDocument11 pagesChapter 4: Financial Markets: 4-1 The Demand For Moneynejla ben mimounNo ratings yet

- Module 5 NotesDocument9 pagesModule 5 Notesfosejo7119No ratings yet

- 6 Money SupplyDocument6 pages6 Money SupplySaroj LamichhaneNo ratings yet

- 10 Rules of EconomicsDocument4 pages10 Rules of EconomicsJames GrahamNo ratings yet

- Princ ch29 PresentationDocument34 pagesPrinc ch29 PresentationSandra Hanania PasaribuNo ratings yet

- Definition: The Total Stock of Money Circulating in An Economy Is The Money Supply. TheDocument7 pagesDefinition: The Total Stock of Money Circulating in An Economy Is The Money Supply. TheSufian HimelNo ratings yet

- Lecture No.6 (Updated - For CLASS)Document26 pagesLecture No.6 (Updated - For CLASS)Deep ThinkerNo ratings yet

- Barter SystemDocument27 pagesBarter SystemimadNo ratings yet

- Chap 5 Money Supply and Bank NegaraDocument59 pagesChap 5 Money Supply and Bank NegaraDashania GregoryNo ratings yet

- MACRO Lecture2 Money 2Document36 pagesMACRO Lecture2 Money 2Fariha KhanNo ratings yet

- Money Function CompDocument38 pagesMoney Function CompvikramadityasinghdevNo ratings yet

- Macro-C29 Monetary SystemDocument36 pagesMacro-C29 Monetary SystemNguyen Thi Kim Ngan (K17 HCM)No ratings yet

- Princ Ch29 PresentationDocument30 pagesPrinc Ch29 PresentationVân HảiNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics I: Dr. Tu Thuy Anh Faculty of International EconomicsDocument15 pagesMacroeconomics I: Dr. Tu Thuy Anh Faculty of International EconomicsDuyen DoanNo ratings yet

- Princ Ch29 PresentationDocument36 pagesPrinc Ch29 PresentationCresca Cuello CastroNo ratings yet

- Apuntes Unit 3Document12 pagesApuntes Unit 3Sara TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Money SupplyDocument22 pagesThe Money SupplyKeychii EmnasNo ratings yet

- CH 29Document36 pagesCH 29Robelen CallantaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Money Supply and Money DemandDocument37 pagesChapter 3 - Money Supply and Money DemandJamalNo ratings yet

- Unit5 MoneyDocument34 pagesUnit5 Moneytempacc9322No ratings yet

- Lecture8 467Document46 pagesLecture8 467chandusgNo ratings yet

- Mankiw Chapter 4 (19) : The Monetary System, What It Is and How It WorksDocument39 pagesMankiw Chapter 4 (19) : The Monetary System, What It Is and How It WorksGuzmán Gil IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Money Supply and Money Demand: AcroeconomicsDocument42 pagesMoney Supply and Money Demand: AcroeconomicsAda Nama 'Mawardy'No ratings yet

- Chapter 29 PowerPoint StudentDocument33 pagesChapter 29 PowerPoint StudentNhược NhượcNo ratings yet

- Financial Markets: ECON 2123: MacroeconomicsDocument40 pagesFinancial Markets: ECON 2123: MacroeconomicskatecwsNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 5 Chapter 4&5Document3 pagesTutorial 5 Chapter 4&5Renee WongNo ratings yet

- List and Explain The Three Characteristics of Money.: Difficulty: E Type: DDocument22 pagesList and Explain The Three Characteristics of Money.: Difficulty: E Type: DMeshack MateNo ratings yet

- Case, Fair and Oster Chapter 10 Problems Money Supply and Federal ReserveDocument3 pagesCase, Fair and Oster Chapter 10 Problems Money Supply and Federal ReserveRayra AugustaNo ratings yet

- Ec103 Week 07 and 08 s14Document31 pagesEc103 Week 07 and 08 s14юрий локтионовNo ratings yet

- Ch2 (Supply of Money)Document22 pagesCh2 (Supply of Money)Rezuanul RafiNo ratings yet

- Practice Set 9 AnswersDocument7 pagesPractice Set 9 AnswersRomit BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Money SupplyDocument3 pagesIntroduction To The Money SupplyamitwaghelaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Money MarketDocument35 pagesAnalysis of Money MarketchikkuNo ratings yet

- Meb MergedDocument120 pagesMeb MergedMEHUL PALNo ratings yet

- MIT14 02F09 Lec10Document27 pagesMIT14 02F09 Lec10mkmusaNo ratings yet

- Groups 3 Qna The Monetary System What It Is and How It Works PDFDocument8 pagesGroups 3 Qna The Monetary System What It Is and How It Works PDFNing Ai SatyawatiNo ratings yet

- Practice Set 9 Dem GSCMDocument7 pagesPractice Set 9 Dem GSCMRomit BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Money and Money Demand: in This Chapter, You Will LearnDocument24 pagesMoney and Money Demand: in This Chapter, You Will LearnK.m.khizir AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ch. 12 MoneyDocument30 pagesCh. 12 Moneylauravertelcanada2023No ratings yet

- Money Demand & Money SupplyDocument25 pagesMoney Demand & Money SupplyNabeel Mahdi AljanabiNo ratings yet

- The Monetary System: Prepared by FacultyDocument44 pagesThe Monetary System: Prepared by FacultyBUSHRA ZAINABNo ratings yet

- Lecture 21 (19th Jan, 2009)Document16 pagesLecture 21 (19th Jan, 2009)sana ziaNo ratings yet

- Form Voucher - Kas BankDocument14 pagesForm Voucher - Kas BankabcdNo ratings yet

- Instruments of Tax SavingDocument10 pagesInstruments of Tax Savinganilpipaliya117No ratings yet

- Insunews: Weekly E-NewsletterDocument30 pagesInsunews: Weekly E-NewsletterHimanshu PantNo ratings yet

- Investment PlanDocument23 pagesInvestment PlanKhizar WaheedNo ratings yet

- Questions AnswersDocument3 pagesQuestions AnswersajitNo ratings yet

- Anual Report AmfundDocument48 pagesAnual Report AmfundAaron FooNo ratings yet

- A Minor Project ON "Consumer Perception Towards Adoptiong Electronic Payments System in Mayur Vihar Phase 3"Document22 pagesA Minor Project ON "Consumer Perception Towards Adoptiong Electronic Payments System in Mayur Vihar Phase 3"Anshika SharmaNo ratings yet

- RBD - HOUSING Loan AnnexureDocument2 pagesRBD - HOUSING Loan Annexurer_awadhiyaNo ratings yet

- Credit Cards: Statement of AccountDocument4 pagesCredit Cards: Statement of AccountLuis AngNo ratings yet

- Account Opening FormDocument19 pagesAccount Opening Formrgsr2008No ratings yet

- Financial Ratio Analysis of HealthsouthDocument11 pagesFinancial Ratio Analysis of Healthsouthfarha tabassumNo ratings yet

- BankDocument73 pagesBankSunil NikamNo ratings yet

- DepreciationDocument14 pagesDepreciationKris Hazel RentonNo ratings yet

- Account StatementDocument12 pagesAccount StatementSanjeev JoshiNo ratings yet

- Fitch Ratings - Brief ProfileDocument41 pagesFitch Ratings - Brief ProfileSona PansariNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow DissertationDocument6 pagesCash Flow DissertationHelpWritingACollegePaperCanada100% (2)

- Barcoma-Acce 412 (11435) - Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesBarcoma-Acce 412 (11435) - Reaction PaperDiana Mae BarcomaNo ratings yet

- Importance of Banks in An Economy: by Rudo ChengetaDocument18 pagesImportance of Banks in An Economy: by Rudo ChengetashanfaizaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Perception Plastic MoneyDocument58 pagesConsumer Perception Plastic MoneyVasu ThakurNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Getting Funding or FinancingDocument33 pagesChapter 4 Getting Funding or Financingj9cc8kcj9wNo ratings yet

- Estadistica Eje 2Document13 pagesEstadistica Eje 2valentina serna ramirezNo ratings yet

- DSPBR Common Application and SIP FormDocument3 pagesDSPBR Common Application and SIP FormsaileshNo ratings yet

- WSS 9 Case Studies Blended FinanceDocument36 pagesWSS 9 Case Studies Blended FinanceAbdullahi Mohamed HusseinNo ratings yet

- Impact of Recent Innovation and Entrant On Traditional BanksDocument19 pagesImpact of Recent Innovation and Entrant On Traditional BanksKasim KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 06Document25 pagesChapter 06Farjana Hossain DharaNo ratings yet

- Project DunbarDocument63 pagesProject DunbarFred aspenNo ratings yet

- Impact of Basel III On Financial MarketsDocument4 pagesImpact of Basel III On Financial MarketsAnish JoshiNo ratings yet