Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Dr. Bao

Uploaded by

Moch. Ivan Kurniawan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views13 pagesm m m m

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentm m m m

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views13 pagesJurnal Dr. Bao

Uploaded by

Moch. Ivan Kurniawanm m m m

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

Family history of cancer,

Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry,

and pancreatic cancer risk

Eldwin Laurenso Lomi 201704200235

Ervina Stya Insanul H 201704200242

BACKGROUND

• Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality

in the United States (U.S.) with an overall 5-year survival rate of <10%.

This high mortality rate is largely related to the diagnosis of patients at

advanced stages when the disease is unresectable and thus incurable.

Therefore, there is a great need for identification of risk factors for

pancreatic cancer and establishment of screening strategies to reduce

mortality asso- ciated with this malignancy.

• Individuals with a family history of pancreatic cancer carry increased

risks of pancreatic cancer and other cancer types. In addition to

environmental and lifestyle factors shared by family members, studies

have identified genes that contribute to familial clustering of

pancreatic cancer, including ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN2A, and PALB2,

as well as PRSS1 and SPINK1 for hereditary pancreatitis. Evidence also

links family history of other cancer

BACKGROUND

• types to increased risk of pancreatic cancer. BRCA1 and BRCA2 for

hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, DNA mismatch repair genes

responsible for Lynch syndrome, and CDKN2A for familial atypical

multiple melanoma and mole syndrome may contain underlying

germline mutations that predispose to pancreatic cancer and other

cancer types. However, the association of family history of various

cancer types with risk of pancreatic cancer has not been fully

evaluated in prospective studies with long duration of follow-up.

Furthermore, individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) heritage represent a

genetically distinct population, which is characterised by higher

prevalence of germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, MSH2, and MSH6,

and higher incidence of various malignancies including pancreatic

cancer. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)

guidelines recommend genetic counselling for AJ individuals diagnosed

with pancreatic cancer. Yet, the association of family history with risk

of pancreatic cancer is not well defined in the context of religious

heritage.

Materials and Methods

• Study Population

• Assessment of family history of cancer

• Ascertainment of covariates

• Statistical analysis

Study population

• We collected data from an ongoing prospective cohort study in the U.S., the Health

Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS). In 1986, the HPFS cohort was established when 51,529

male health professionals aged 40–75 years (dentists, optometrists, osteo- paths,

pharmacists, podiatrists, and veterinarians) returned a baseline questionnaire. Participants

have been sent questionnaires to report demographics, medical and social history, and health

outcomes such as cancer diagnoses every 2 years, and to report dietary patterns every 4

years. Participants were followed until diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, death from

any cause, or the end of follow-up (31 January 2016), whichever came first. The follow-up

rate has been more than 90% for each follow-up questionnaire cycle. Informed consent was

obtained from all participants at study enrolment, and the HPFS was approved by the

institutional review board at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Boston, MA, USA).

• Patients with pancreatic cancer were identified by self-report, next-of-kin, or review of the

National Death Index. Physicians blinded to exposure data confirmed the diagnosis of

pancreatic adenocarcinoma by review of medical records, death certificates, or cancer

registry data. Deaths were ascertained based on information from next of kin, U.S. postal

service, and/or the National Death Index; this method has been shown to capture >98% of

deaths. We excluded participants with a history of cancer at baseline (exception of non-

melanoma skin cancer) and those without available data on family history of cancer.

Assessment of family history of

cancer

• We utilised data on family history of cancer in first-degree

relatives including parents, siblings, and offspring which have

been prospectively collected from questionnaires. Family history

was assessed in 1996 for breast cancer; in 1986, 1990, 1992,

1996, 2008, and 2012 for colorectal cancer; in 2008 for

pancreatic cancer; in 1990, 1992, and 2008 for melanoma; in

1990, 1992, and 1996 for prostate cancer; and in 1992 for lung

cancer. A positive family history for each cancer type was

defined when the participant reported any first-degree relative

diagnosed with the correspond- ing cancer. Participants were

treated as those with a family history of a specific cancer type

from the first report of a first-degree relative diagnosed with the

cancer. Follow-up time for the analysis of each cancer type

started at the first year when a family history of the cancer was

assessed.

DISCUSSION

• Within a large U.S. cohort with 30 years of follow-up, we

prospectively examined the association of family history of

cancer with risk of incident pancreatic cancer. Specifically,

we evaluated family history of melanoma and breast,

colorectal, lung, pancreatic,or prostate cancer. Notably,

family history of breast cancer was associated with

approximately 40% higher risk of developing pancreatic

cancer over the study follow-up period. Furthermore, in

stratified analyses, participants with both diabetes mellitus

and a family history of breast or colorectal cancer had a

greater than 2-fold risk of developing pancreatic cancer.

• Although increased risk of pancreatic cancer has

been also reported among individuals with a family

history of other cancer types, data from prospective

studies are limited with inconsistent conclusions. In

a prospective study of a U.S.-based cohort, family

history of breast and colorectal cancer was

associated with modestly increased pancreatic

cancer mortality with HRs.

• Data from a large cancer registry in Sweden

suggested no significant increase in pancreatic

cancer incidence associated with positive family

history of breast, colon, and rectal cancer with

standardised incidence ratios (SIRs)

• Shared genetic architecture may contribute to familial predisposition to

multiple cancer types. For pancreatic cancer, these alterations may

include germline high penetrance mutations in the DNA double-strand

break repair genes responsible for inherited breast and ovarian cancer

(e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2) and the DNA mismatch repair genes

responsible for Lynch syndrome (e.g., MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2).

• The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium reported the relative risk for

pancreatic cancer of 2.26 (95% CI, 1.26–4.06) for BRCA1 mutation

carriers and 3.51 (95% CI, 1.87–6.58) for BRCA2 mutationcarriers.16,17 A

prospective study reported a SIR for pancreatic cancer of 10.68 (95% CI,

2.68–47.70) among 446 carriers of a mismatch repair gene mutation.

The aggregate of multiple lowpenetrance single nucleotide variants may

also contribute to shared risk of multiple malignancies.

• Few prospective studies have evaluated the association of family

history with risk of pancreatic cancer after considering religious

heritage. In the current study, family history of breast and

colorectal cancer appeared to be more strongly associated with

risk of pancreatic cancer in AJ men than in non-AJ men. AJ

individuals are at higher risk of several cancer types

includingpancreatic cancer. Ashkenazi Jews are known to have

founder mutations in BRCA1 (reported in 0.4% and 0.1%,

respectively, of Ashkenazi women) and BRCA2 ( reported in 0.6%

Ashkenazi women) underlying hereditary breast cancer. They

also have founder mutationsin MSH2 (reported in 0.44%

Ashkenazi Jews with colorectal cancer) and MSH6 (reported in

0.11% and 0.30%, respectively, of Ashkenazi Jews with colorectal

cancer) underlying Lynch syndrome. Those founder mutations

may contribute to predisposition to pancreatic cancer.

• Taken together, family history of breast or

colorectal cancer in Ashkenazi Jews may

mark a population with high risk of

pancreatic cancer mediated through genetic

alterations in these genes or others.

Considering the joint risk estimates

associated with a family history of breast or

colorectal cancer, AJ ancestry, and diabetes

status may assist in defining high-risk

populations for disease screening.

• Our study has notable strengths, including a

prospective study design, large sample size with

over 400 pancreatic cancer cases, and availability of

religious heritage data. The data on family history

and covariates were collected prospectively and

updated repeatedly, which allowed us to rigorously

adjust for potential confounders, to evaluate effect

modification by other risk factors, and more

importantly, to assess cancer family history without

substantial recall bias, which can be a major

problem when analysing family history data after a

cancer diagnosi

• In conclusion, family history of breast cancer in one

or more first-degree relatives was associated with

increased incidence of pancreatic cancer in a large

prospective cohort study of U.S. men. Individuals

with a family history of colorectal cancer appeared

tocarry a modestly increased risk of pancreatic

cancer. These associations were more pronounced

among individuals of AJ descent and with a history

of diabetes mellitus. Therefore, family history of

other malignancies may be relevant for

determiningpancreatic cancer risk, particularly when

combined with knownrisk factors for this disease.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- ISO 11064-12000 Ergonomic Design of Control Centres - Part 1 Principles For The Design of Control Centres by ISO TC 159SC 4WG 8Document6 pagesISO 11064-12000 Ergonomic Design of Control Centres - Part 1 Principles For The Design of Control Centres by ISO TC 159SC 4WG 8marcianocalvi4611100% (2)

- 28 ESL Discussion Topics Adult StudentsDocument14 pages28 ESL Discussion Topics Adult StudentsniallNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 DiathermyDocument63 pagesUnit 3 DiathermyAan Ika SugathotNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Voters ListDocument86 pagesPreliminary Voters Listمحمد منيب عبادNo ratings yet

- Refrensi Trauma KemihDocument1 pageRefrensi Trauma KemihMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- BIO Chem Physio D I S E A S EDocument4 pagesBIO Chem Physio D I S E A S EMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Refrensi Trauma KemihDocument1 pageRefrensi Trauma KemihMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- 3Document6 pages3Moch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Seven JumpDocument22 pagesSeven JumpMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

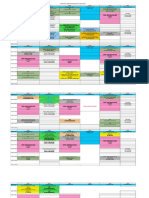

- Jadwal Blok THT Mata 2017 (1) Edit 1Document4 pagesJadwal Blok THT Mata 2017 (1) Edit 1Moch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Blepharitis 4Document2 pagesBlepharitis 4Moch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Blok Tropmed Sem 7 FK UHT 2017-2018Document5 pagesJadwal Blok Tropmed Sem 7 FK UHT 2017-2018Moch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading KulitDocument6 pagesJournal Reading KulitsintamirosmalindaNo ratings yet

- Ocular Toxoplasmosis - An Update and Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesOcular Toxoplasmosis - An Update and Review of The LiteratureMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Conjugata VeraDocument21 pagesConjugata VeraMoch. Ivan KurniawanNo ratings yet

- CV Old NicDocument4 pagesCV Old NicTensonNo ratings yet

- Accounting For A Service CompanyDocument9 pagesAccounting For A Service CompanyAnnie RapanutNo ratings yet

- Corporate Profile of Multimode GroupDocument6 pagesCorporate Profile of Multimode GroupShaheen RahmanNo ratings yet

- Wa200-8 Venss06304 1904 PDFDocument24 pagesWa200-8 Venss06304 1904 PDFOktiano BudiNo ratings yet

- SmoothWall Express 2.0 Quick-Start GuideDocument6 pagesSmoothWall Express 2.0 Quick-Start Guideinfobits100% (1)

- A Control Method For Power-Assist Devices Using A BLDC Motor For Manual WheelchairsDocument7 pagesA Control Method For Power-Assist Devices Using A BLDC Motor For Manual WheelchairsAhmed ShoeebNo ratings yet

- MELASMA (Ardy, Kintan, Fransisca)Document20 pagesMELASMA (Ardy, Kintan, Fransisca)Andi Firman MubarakNo ratings yet

- STS Reviewer FinalsDocument33 pagesSTS Reviewer FinalsLeiNo ratings yet

- Buy Wholesale China Popular Outdoor Football Boot For Teenagers Casual High Quality Soccer Shoes FG Ag Graffiti Style & FootballDocument1 pageBuy Wholesale China Popular Outdoor Football Boot For Teenagers Casual High Quality Soccer Shoes FG Ag Graffiti Style & Footballjcdc9chh8dNo ratings yet

- Auburn Bsci ThesisDocument5 pagesAuburn Bsci Thesisafksaplhfowdff100% (1)

- L&T Motor CatalogDocument24 pagesL&T Motor CatalogSanjeev DhariwalNo ratings yet

- Probecom 11.3M Antenna System Datasheet 2Document2 pagesProbecom 11.3M Antenna System Datasheet 2Hugo MateoNo ratings yet

- Lahainaluna High School Cafeteria: Lahaina, Maui, HawaiiDocument42 pagesLahainaluna High School Cafeteria: Lahaina, Maui, HawaiiKeerthy MoniNo ratings yet

- MSS SP 69pdfDocument18 pagesMSS SP 69pdfLaura CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Luyện nghe Tiếng Anh có đáp án: I/ Listen and complete the textDocument3 pagesLuyện nghe Tiếng Anh có đáp án: I/ Listen and complete the textVN LenaNo ratings yet

- In Other Words RE Increased by P250,000 (Income Less Dividends)Document6 pagesIn Other Words RE Increased by P250,000 (Income Less Dividends)Agatha de CastroNo ratings yet

- Haldex Valve Catalog: Quality Parts For Vehicles at Any Life StageDocument108 pagesHaldex Valve Catalog: Quality Parts For Vehicles at Any Life Stagehoussem houssemNo ratings yet

- Audit Committee and Corporate Governance: CA Pragnesh Kanabar Sir's The Audit Academy-CA Final AuditDocument17 pagesAudit Committee and Corporate Governance: CA Pragnesh Kanabar Sir's The Audit Academy-CA Final AuditPULKIT MURARKANo ratings yet

- Maryam Ejaz Sec-A Marketing Assignment (CHP #15)Document3 pagesMaryam Ejaz Sec-A Marketing Assignment (CHP #15)MaryamNo ratings yet

- Daewoo SJ-210H DSJ-6000LHMDocument44 pagesDaewoo SJ-210H DSJ-6000LHMMarco Antonio100% (5)

- Sorting Algorithms in Fortran: Dr. Ugur GUVENDocument10 pagesSorting Algorithms in Fortran: Dr. Ugur GUVENDHWANIT MISENo ratings yet

- Cell Structure, Cellular Respiration, PhotosynthesisDocument14 pagesCell Structure, Cellular Respiration, PhotosynthesisAmr NasserNo ratings yet

- (IGC 2024) 2nd Circular - 0630Document43 pages(IGC 2024) 2nd Circular - 0630VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 First Quarter ExamDocument3 pagesGrade 7 First Quarter ExamBILLY JOE ARELLANONo ratings yet

- T10 - PointersDocument3 pagesT10 - PointersGlory of Billy's Empire Jorton KnightNo ratings yet

- Introductions and Basic Personal Information (In/Formal Communication)Document6 pagesIntroductions and Basic Personal Information (In/Formal Communication)juan morenoNo ratings yet

- Pe8 Mod5Document16 pagesPe8 Mod5Cryzel MuniNo ratings yet