Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FIX BOOK Reading Treatment Fracture

Uploaded by

Selma Mutiara0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views52 pagesOriginal Title

FIX BOOK reading treatment fracture.pptx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views52 pagesFIX BOOK Reading Treatment Fracture

Uploaded by

Selma MutiaraCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 52

BOOK READING

dr. Sholahuddin Rhatomy, Sp.OT

Selma Mutiara Hani

Nadia Dini Yulianti

Felicia Seruni Sekar Asri

Treatment For Fracture

the four basic goals of all fracture treatment :

1) to relieve pain

2) to obtain and maintain satisfactory position of the fracture

fragments

3) to allow, and if necessary encourage, bony union

4) to restore optimum function, not only in the fractured limb or spine

but also in the patient as a person

treatment for closed fracture

• Protection Alone (without Reduction or Immobilization)

Indication : Protection alone is indicated for undisplaced or

relatively undisplaced, stable fractures of the ribs,

phalanges, metacarpals-and in children, of the clavicle. A

second indication is that group of fractures, such as mild

compression fractures of the spine and impacted fractures

of the upper end of the humerus, in which the total result

will be better without either reduction or immobilization.

Protection alone is also indicated after clinical union has

been obtained by other means) but before complete

radiological consolidation has been established.

Risk : The protection provided may not be adequate for the

particular patient (especially a very young child or an

uncooperative adult), in which case the fracture may become

displaced; hence, the need for radiographic examinations of the

fracture site at re gular intervals during the healing process.

treatment for closed fracture

• Immobilization by External Splinting (without Reduction)

• Immobilization of a fracture by external splinting is only

relative immobilization, as opposed to rigid fixation, in as

much as some motion can still occur inside the limb or trunk

at the fracture site during the early phases of healing.

Relative immobilization is usually, achieved by the use of

plaster-of-Paris casts of varying design and occasionally by

metallic or plastic splints

• Indication : Immobilization by external splinting without

reduction is indicated for fractures that are relatively

undisplaced, yet unstable.

• Such fractures merely require maintenance of the existing position of

the fracture fragments during the healing process. A long bone

fracture in which there is only sideways shift of the fragments in

relation to one another but good contact and no significant angulation

or rotation does not re- quire reduction; it does, however, require

relative immobilization

• Risk : subsequent muscle pull and gravitational forces may cause

further displacement such as angulation, rotation) or overriding that is

unacceptable; hence the need for repeated radiographic

examinations during the early stages of healing. Improperly applied

casts or splints may cause local pressure sores over bone

prominences, or constriction of a limb with resultant impairment of

venous or arterial circulation, or both.

treatment for closed fracture

• Closed Reduction by Manipulation Followed by Immobilization

Closed reduction of a fracture, which is a form of surgical

manipulation, is by far the most common method of treatment for

the majority of displaced fractures in both children and adults.

Immobilization of the fracture by means of a plaster-of-Paris cast is

the most common method of maintaining the reduction.

in general it involves placing the fracture fragments where they

were at the time of maximal displacement and then reversing the

path of displacement.

Indication : Closed reduction by manipulation followed by

immobilization is indicated for displaced fractures that require

reduction and when it is predicted that sufficiently accurate

reduction can be both obtained. and maintained by closed means.

• Risk : Closed reduction that is ineptly and inaptly applied with more

force than skill may cause further damage to soft tissues

including blood vessels) nerves and even the periosteum.

Excessive traction in the longitudinal axis of the limb during

reduction may even produce arterial spasm particularly at the

elbow and knee, with resultant Volkmann's ischemia. Pressure

sores over bony prominences and pressure injuries to

peripheral nerves over bony prominences (especially the lateral

popliteal nerve where it crosses the neck of the fibula) may also

occur . Fractures in which the reduction is not sufficiently stable,

especially oblique, spiral, and comminuted fractures, may become

displaced subsequently within the cast and repeated radiographic

assessments of the positron of the fragments are essential during

the early stages of healing.

treatment for closed fracture

• Closed Reduction by Continous Traction followed by

Immobilization

• For fractures in young children, continuous traction can be

applied through the skin by means of extension tape (skin

traction) .For older children and adults in whom greater traction

force is required, it is best applied through bone by means of a

transverse rigid wire or pin (skeletal traction). Furthermore, the

traction device may be fixed to the end of the bed (fixed

traction), or it may be balanced by cords with pulleys and

weights (balanced traction)

• Indication : Closed reduction by continuous traction is

indicated for unstable oblique, spiral, or comminuted fractures

of major long bones, and unstable spinal fractures. Skeletal

traction is also applicable to the treatment of fractures

complicated by vascular injuries) excessive swelling, or skin

loss in which an encircling bandage or cast would be

dangerous.

• Risk = excessive longitudinal traction cause arterial spasm with

resultant Volkmann's ischemia (compartment syndrome). Ineptly

applied skin traction) excessive traction, or both may result in

superficial skin loss, whereas skeletal traction may become

complicated by pin track infection that reaches the bone. if

inaccurate, applied and monitored, may fail to achieve and

maintain adequate reduction of the fracture. Excessive traction may

also distract the fracture fragments with resultant delayed union or

even nonunion; osteoblasts can creep but cannot leap.

treatment for closed fracture

• Closed Reduction Followed by Functional Fracture-Bracing

• The principle of functional fracture-bracing is based on the

following concepts: I ) that rigid immobilization of fracture

fragments is not only unnecessary but also undesirable for

fracture healing; 2) that function and the resultant controlled

motion at the fracture site actually stimulate healing through

abundant callus formation; 3) that such function prevents

iatrogenic joint stiffness; 4) that some what less than perfect

(anatomical) reduction of a fracture of the shaft of a long

bone does not create significant problems concerning either

function or appearance (cosmesis)

• Indication : Closed reduction followed by functional fracture-

bracing is indicated for fractures of the shaft of the tibia, the

distal third of the femur, the humerus, and the ulna in adults.

The method is contraindicated for fractures drat can be more

effectively treated by open reduction and internal skeletal

fixation, including intertrochanteric fractures of the femur,

subtrochanteric and mid-shaft frac- tures of the femur, and

shaft of the radius and intra- articular fractures.

• Risk : Although functional fracture-bracing is relatively risk

free, there is a possibility that the method will fail to maintain

an acceptable position of the fracture fragments, in which case

alternative methods such as open reduction and internal

fixation may still be applied.

treatment for closed fracture

• Closed Reduction by Manipulation Followed by External skeletal

Fixation

Indications: for severely comminuted (and unstable) fractures of the

shaft of the tibia or femur, especially type 3 open fractures with

extensive injuries to soft tissues including arteries and nerves, the

repair of which necessitates immobilization of the fracture site.

External skeletal fixation may also be indicated for unstable fractures

of the pelvis, humerus, radius, and metacarpals

Risks: The main risk of external skeletal fixation is pin track infection

with or without osteomyelitis. If the pins are inserted by means of a

high-speed pourer drill, the surrounding bone may be "burnt to death"

by the heat of friction, in which case superimposed infection will

produce a ring sequestrum.

treatment for closed fracture

• Closed Reduction by Manipulation Followed by Internal skeletal

Fixation

Indications: for certain fractures in which accurate reduction can be

obtained by closed means but cannot or should not be maintained by

external immobilization, for example unstable fracture of the neck of the

femur in both children and adults. After accurrate reduction, the internal

fixation device is driven across the fracture site through a small skin

incision using radiographic control. Certain fractures in the midshaft of

the long bones that can be reduced by closed means also lend

themselves to blind intramedullary nailing under radiographic control.

Risks: The closed manipulative reduction may fail to obtain a

satisfactory position of the fracture fragments and the skeletal fixation

may fail to achieve sufficiently rigid fixation of the fracture. Because with

internal skeletal fixation the skin is traversed, the risk of infection is ever

present.

treatment for closed fracture

• Open Reduction Followed by Internal Skeletal Fixation

The operative reduction of fractures should be performed (or at least

supervised) only by an experienced surgeon and only in a favorable setting

such as an operating theater that has a consistently low infection rate and is

properly equipped with adequate instruments. Once the fracture has been

reduced at open operation, the reduction must be maintained by internal

fixation, which is achieved by using some type of metallic device, a technique

that is sometimes referred to as osteosynthesis.

Indications: where there is a coexistent vascular injury that requires

exploration and repair, displaced avulsion fractures, intra-articular fractures in

which reduction of the joint surface must be perfect, displaced fractures in

children that cross the epiphyseal plate (physis), and fractures in which soft

tissues have become interposed and trapped between the fragments.

Risks: infection, also carries the risk of further damage to the blood. supply of

the fracture fragments which, in turn, may lead to delayed union and even

nonunion.

treatment for closed fracture

• Excision of a Fracture Fragment and Replacement by an

Endoprosthesis

Indications: Because of the high incidence of avascular necrosis of

the femoral head and nonunion of the fracture, displaced intracapsular

fractures of the neck of the femur in the elderly cannot always be

managed satisfactorily by internal fixation. Comminuted fractures of the

radial head in adults are not amenable to internal fixation. If the elbow

joint is grossly unstable as a result of coexistent ligamentous injury, the

radial head may be replaced by an endoprosthesis. For severely

comminuted and grossly, unstable supracondylar fractures of the

humerus in adults, an elbow prosthesis may be required

Risks: infection, there is also a risk, particularly in the elderly hip, that

the endoprosthesis will gradually migrate through osteoporotic bone of

the pelvis or femur.

Treatment for open fracture

• Prevention of infection and obtaining union of the fracture.

• The extent of the skin wound of an open fracture varies considerably. It may be a

small puncture wound caused by penetration of the skin from within by a sharp,

jagged spike of bone (Fig. 15.10), or by penetration of the skin from without by a

missile such as a bullet. The wound may be a sizeable tear in the skin through which

bare bone is still protruding.

• Classification of open fracture (Gustilo & Anderson):

1. Type 1 : clean wound less than I cm in length (usually from within with little soft tissue

injury)

2. Type 2 : a laceration more than I cm in length but without extensive soft tissue

damage, skin flaps, or avulsions and with a simple transverse or oblique fracture

3. Type 3A : extensive soft tissue damage but adequate bone coverage, segmental

fractures and gunshot wounds

4. Type 3B : extensive soft tissue damage with extensive periosteal stripping and

devascularized bone that requires skin flaps or free grafts. This type is usually

associated with gross contamination

Treatment for Open Fractures

• Because open (compound) fractures have communicated with

the external environment through the skin and have already

been complicated by bacterial contamination, they carry the

serious risk of becoming further complicated by infection.

• Emphasis on the prevention of infection and obtaining

union of the fracture.

• Because of the extensive soft tissue injury associated with

open fractures, they usually take much longer to unite than

closed fractures.

• An instant ("polaroid") photograph should be taken of every

open fracture in the emergency room before a sterile

dressing has been applied, or in the operating room, to

provide an important item for the hospital record and to avoid

the risk of additional contamination from repeated

preoperative inspections of the open wound by consulting

surgeons.

Classification of Open Fractures

Gustilo and Anderson were able to distinguish three distinct categories, based on the

severity of the soft tissue injury :

• Type 1 : a clean wound less than I cm in length (usually from within with little soft

tissue injury);

• Type 2 : a laceration more than I cm in length but without extensive soft tissue

damage, skin flaps, or avulsions and with a simple transverse or oblique fracture;

• Type 3 : extensive soft tissue damage such as skin flaps, avulsions, and muscle and

nerve injuries.

More recently, Gustilo has described three categories of type 3 open fractures:

• 3A : extensive soft tissue damage but adequate bone coverage, segmental

fractures, and gunshot wounds;

• 3B : extensive soft tissue damage with extensive periosteal stripping and

devascularized bone that requires skin flaps or free grafts. This type is usually

associated with gross contamination;

• 3C : associated vascular injury requiring repair.

• The authors recommended primary closure of the skin in

types I and 2 open fractures (this is controversial) but

delayad primary closure in type 3 open fractures.

• In many trauma centers, open fractures are left open initially,

that is, for the first 4 to 7 days.

• Using antibiotics (usually one of the cephalosporins) before,

during, and after operation, the overall infection rate was 2,4

% whereas the infection rate for type 3 injuries alone was

l0%.

Aspects of Treatment for Open Fractures

Cleansing the Wound :

• Gross dirt, bits of clothing, and other foreign material should

be literally washed away by extensive pulsating irrigation as

well as by mechanical cleansing with copious amounts of

sterile water or isotonic saline (rather than merely

camouflaged by strong antiseptics that cause further tissue

damage).

• The wound may even have to be opened further to allow

adequate assessment of the degree of contamination and to

deal with it.

Excision of Devitalized Tissue (Debridement).

• Because tissues that have lost their blood supply prevent

primary wound healing and enhance infection, the

meticulous surgical excision of all devitalized tissue, such as

skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, muscle, and loose fragments of

bone, is essensial.

• It also is wise to obtain a culture of the wound at the time of

operation.

Treatment of the Fracture :

• When the open wound is small, such as a puncture wound from

within, the fracture can usually be treated by closed means, after

the wound has been cleansed, debrided, and left open.

• In general, internal fixation may be used unless it is thought that

its mere insertion would tend to traumatize and devitalize more

tissue and increase the risk of infection.

• Under certain circumstances, such as excessive instability of the

fracture or an associated vascular injury, internal fixation is

completely justified because the risks of its application are less

serious than the risks of alternative methods.

Closure of the Wound :

• Even when the open fracture is treated within "the golden period" of

the first 6 or 7 hours and contamination is not extensive,

immediate primary closure of the wound is usually

contraindicated, in keeping with the aphorism "leave open

fractures open." After the first 4 to 7 days, provided no infection

has developed, delayed primary closure of the wound is

indicated.

• Loss of skin may necessitate the delayed application of split

thickness skin grafts. Suction drainage should be used to prevent

accumulation of blood and serum in the depths of the wound.

• Delayed primary closure is particularly applicable in grossly

contaminated open fractures sustained on the battlefield or in

major disasters.

Antibacterial Drugs :

• To be effective in the prevention of infection, antibacterial

drugs must be administered in large doses before, during, and

after treatment of the wound. Even so, antibacterial treatment

is no guarantee against infection because many bacteria are

resistant to various drugs.

• Furthermore, antibacterial drugs cannot reach any wound

tissue that has lost its blood supply. The surgical care of

the wound is of even greater importance than the

antibacterial therapy.

Prevention of Tetanus :

• All patients with open fractures require preventive measures

against the uncommon but serious complication of tetanus.

• If the patient has been previously immunized by tetanus

toxoid, a booster dose of toxoid should be given.

• If there has been no previous immunization, or if inadequate

information is available, immediate passive immunity can be

achieved by the use of 250 units of tetanus immune

globulin (human). Active immunity with tetanus toxoid is

initiated at the same time.

Anesthesia for Patients with Fractures

• During the first hour after a fracture has occurred, the

patient's tissues are somewhat numb and under these

circumstances only, it may be possible to reduce certain

fractures without anesthesia.

• Even then, however, reduction without anesthesia should be

performed only if the physician or surgeon is confident that it

can be accomplished with one deft manipulation and the

patient is not unduly tense and nervous.

• Certain fractures, such as a Colles' fracture at the lower end of

the radius in adults, are amenable to reduction after

infiltration of a local anesthetic agent in and around the

fracture site.

• Other fractures in the limbs can be reduced under regional

anesthesia such as a brachial plexus block for the upper

limb and a spinal anesthetic for the lower limb.

• In general, the majority of fractures requiring reduction are

best treated under general anesthesia, which provides

complete comfort and the muscle relaxation necessary in

reducing a fracture.

• The risk of aspiration of stomach contents during the

induction of general anesthesia as well as during the

recovery period merits special mention in relation to patients

with fractures.

• After a significant injury, such as a fracture, gastric motility

virtually ceases for many hours and consequently, if the

patient has ingested food or drink shortly before or after the

injury, the stomach retains a mixture of undigested food and

gastric acid, either of which can cause death if aspirated into

the trachea or lungs.

• Under these circumstances, unless there is a serious

complication such as an open fracture or a vascular injury,

general anesthesia should be delayed until at least 6 hours

after the ingestion of food or drink; even after this period,

special precautions, such as removal of gastric contents

through a tube, are necessary to prevent the serious

complication of aspiration.

• The welfare of the patient must always take precedence over

the convenience of his or her physician or surgeon.

• Temporary splints should not be removed nor the fractured

part be moved during the preliminary stages of anesthesia, or

the painful stimulus could initiate either cardiac arrest or

laryngeal spasm.

After-Care and Rehabilitation for Patients with

Fractures

Four aims of all fracture treatment are :

1. to relieve pain;

2. to obtain and maintain satisfactory position of the fracture

fragments;

3. to allow and if necessary to encourage bony union;

4. to restore optimum function.

The most important is restoration of function.

• Excessive and persistent edema in soft tissues produces

glue-like adhesions with resultant joint stiffness.

• It should be prevented or minimized by appropriate elevation

of the fractured limb during the early phase of fracture healing,

as well as by improvement of venous return through active

exercises of all regional muscles.

• Muscles that are not used soon exhibit disuse atrophy, which

can be prevented by active static (isometric) exercises of

those muscles that control the immobilized joints, and active

dynamic (isotonic) exercises of all other muscles of the limb

or trunk.

• Supervised physiotherapy is particularly important in the after-

care of adults with fractures.

• All joints that are not immobilized by the fracture treatment

should be put through a full range of motion daily by the

patient.

• In addition to presentation of function in the muscles and joints

after a fracture, healthy function in the patient's mind must

also be preserved, because the patient's attitude toward his or

her injury determines to a considerable extent the rate at

which recovery will progress.

• Indeed, psychological consideration added to good care of

the patient's fracture can usually prevent unnecessary

despondency, depression, and undue concern about the

future.

• After the period of external immobilization of the fracture,

active exercises should be continued even more vigorously

until normal muscle power and joint motion have been

regained.

• If necessary, the patient should be retrained in the activities of

daily living and occupation, usually through supervised

occupational therapy.

• Rehabilitation of the whole person, is always important,

especially when the fracture has required a particularly long

period of treatment or has been associated with serious

complications.

Complications of Fracture Treatment

These complications are mostly preventable; they are related to three main

factors: excessive local pressure, excessive traction, and infection.

1. Skin Complications : Tattoo effect from abrasions, Pressure lesions

(pressure sores), Bed sores (decubitus ulcers), Cast sores (cast ulcers)

2. Vascular Complications : Traction and pressure lesions, Volkmann's

ischemia (compartment syndromes), Gangrene and gas gangrene,

Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

3. Neurological Complications : Traction and pressure lesions

4. Joint Complications : Infection (septic arthritis) complicating open

operative treatment of a closed injury

5. Bony Complications : Infection (osteomyelitis) complicating open

operative treatment of a closed injury

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cosmology: Beyond The Big BangDocument60 pagesCosmology: Beyond The Big BangHaris_IsaNo ratings yet

- Jharkhand Bijli Vitran Nigam LimitedDocument2 pagesJharkhand Bijli Vitran Nigam LimitednandksrkumarNo ratings yet

- APO SNP Training - GlanceDocument78 pagesAPO SNP Training - GlanceAshwani SharmaNo ratings yet

- Learning - Module.Facial Care Proj.Document24 pagesLearning - Module.Facial Care Proj.Ria Lopez100% (8)

- Hughes Consciousness and Society 1958Document468 pagesHughes Consciousness and Society 1958epchot100% (1)

- Jama 2017 11469Document10 pagesJama 2017 11469Selma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Supp Mdu526 Mdu526suppDocument37 pagesSupp Mdu526 Mdu526suppSelma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Clinical Relevance of Folinic Acid Over Rescue AFTER HFMTXDocument6 pagesClinical Relevance of Folinic Acid Over Rescue AFTER HFMTXSelma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Sumup Toxi OsDocument21 pagesSumup Toxi OsSelma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Laporan Jaga IGD 24 Juni 2019Document16 pagesLaporan Jaga IGD 24 Juni 2019Selma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- EBM-Internal Med Students-FinalDocument29 pagesEBM-Internal Med Students-FinalSelma MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Statement of Purpose For Studying MechatronicsDocument2 pagesStatement of Purpose For Studying MechatronicsBivash NiroulaNo ratings yet

- My Two Week Meal Plan: Day Date Breakfast Lunch Dinner SignatureDocument1 pageMy Two Week Meal Plan: Day Date Breakfast Lunch Dinner SignatureIan Nathaniel Versoza AmadorNo ratings yet

- My Kind Neighbour Simple Present Grammar Guides Reading Comprehension Exercises Tes - 74419Document1 pageMy Kind Neighbour Simple Present Grammar Guides Reading Comprehension Exercises Tes - 74419algarinejo100% (1)

- Power Transmission, Distribution and Utilization: Lecture# 13 &14: Underground CablesDocument29 pagesPower Transmission, Distribution and Utilization: Lecture# 13 &14: Underground CablesPhD EENo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Mixture and of The Company /undertakingDocument7 pagesSafety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance / Mixture and of The Company /undertakingOrshanetzNo ratings yet

- Linear RegressionDocument541 pagesLinear Regressionaarthi devNo ratings yet

- Digital Photography in OrthodonDocument48 pagesDigital Photography in OrthodonSrinivasan BoovaraghavanNo ratings yet

- Indore BrtsDocument22 pagesIndore BrtsRaj PatelNo ratings yet

- ESL Mid Test Semester 1 Grade 3Document3 pagesESL Mid Test Semester 1 Grade 3Elis ElisNo ratings yet

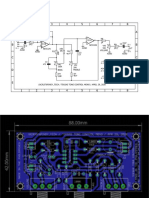

- Teksas Tone Control MonoDocument17 pagesTeksas Tone Control MonoRhenz TalhaNo ratings yet

- Engglis Isma E. N (18010107023) Tadris IpaDocument6 pagesEngglis Isma E. N (18010107023) Tadris IpaLita Dwi HasjayaNo ratings yet

- Martinal LEO - Product RangeDocument6 pagesMartinal LEO - Product RangeAdamMitchellNo ratings yet

- John 8 - 58 - Truly, Truly, I Tell You, - Jesus Declared, - Before Abraham Was Born, I Am!Document8 pagesJohn 8 - 58 - Truly, Truly, I Tell You, - Jesus Declared, - Before Abraham Was Born, I Am!Joshua PrakashNo ratings yet

- Food and DrinkDocument5 pagesFood and DrinkHec Al-HusnaNo ratings yet

- NCM 117 - Case Study 1 DarundayDocument18 pagesNCM 117 - Case Study 1 DarundayEzra Miguel DarundayNo ratings yet

- By: DR Evita Febriyanti Fast Track - Dual Degree 2016 Brawijaya UniversityDocument12 pagesBy: DR Evita Febriyanti Fast Track - Dual Degree 2016 Brawijaya UniversityEvitaFebriyantiPNo ratings yet

- Classified Coordinate Geometry Further Maths ExercisesDocument24 pagesClassified Coordinate Geometry Further Maths ExercisesAbrar RahmanNo ratings yet

- Industry X.0: Realizing Digital Value in Industrial SectorsDocument15 pagesIndustry X.0: Realizing Digital Value in Industrial SectorsJamey DAVIDSONNo ratings yet

- Green Gram CultivationDocument7 pagesGreen Gram CultivationSudhakar JayNo ratings yet

- CTR201Document2 pagesCTR201Vicente RezabalaNo ratings yet

- Tacticity, Geometric IsomerismDocument7 pagesTacticity, Geometric IsomerismbornxNo ratings yet

- 2.1 Energy Flow in An EcosystemDocument13 pages2.1 Energy Flow in An EcosystemJoanne OngNo ratings yet

- Investigation of Liquid-Liquid Phase Equilibria For Reactive Extraction of Lactic Acid With Organophosphorus SolventsDocument6 pagesInvestigation of Liquid-Liquid Phase Equilibria For Reactive Extraction of Lactic Acid With Organophosphorus Solventskudsiya firdousNo ratings yet

- Stories of Love and AdventureDocument24 pagesStories of Love and AdventureMargie HernandezNo ratings yet

- Harga Satuan Precast 2017Document2 pagesHarga Satuan Precast 2017GenTigaBrotherhood BantenNo ratings yet