Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Obligations Nature and Effect of Obligations: Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A

Obligations Nature and Effect of Obligations: Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A

Uploaded by

AllenMaeGarcia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views56 pagesOriginal Title

dokumen.tips_article-1156-1178ppt

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views56 pagesObligations Nature and Effect of Obligations: Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A

Obligations Nature and Effect of Obligations: Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A

Uploaded by

AllenMaeGarciaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 56

OBLIGATIONS

Nature and Effect of Obligations

ART. 1156 – AN OBLIGATION IS A

JURIDICAL NECESSITY TO GIVE, TO

DO OR NOT TO DO.

• an obligation is a legal bond whereby constraint is

laid upon a person or group of persons to act or

forbear on behalf of another person or group of

persons.

• obligation arises from the concurrence of:

a) the vinculum juris or juridical tie;

b) the object which is the prestation;

c) subject-persons (Ang Yu Asuncion v. CA)

ART. 1157 - OBLIGATIONS ARISE FROM:

1)LAW;

2)CONTRACTS;

3)QUASI-CONTRACTS;

4)ACTS OR OMISSIONS PUNISHED BY LAW;

5)QUASI-DELICTS.

• obligations are civil or natural. Civil obligations give a

right of action to compel performance. Natural obligations,

not being based on positive law but on equity and natural

law, do not grant a right of action to enforce performance,

but after their voluntary fulfillment by the obligor, they

authorize the retention of what has been delivered or

rendered by reason thereof.

ART. 1158 - OBLIGATIONS DERIVED FROM

LAW ARE NOT PRESUMED. ONLY THOSE

EXPRESSLY DETERMINED IN THIS CODE OR

IN SPECIAL LAWS ARE DEMANDABLE, AND

SHALL BE REGULATED BY THE PRECEPTS

OF THE LAW WHICH ESTABLISHES THEM;

AND AS TO WHAT HAS NOT BEEN FORSEEN,

BY THE PROVISIONS OF THIS BOOK.

• among sources of obligation, the law is the most

important one. It does not depend upon the will of the

parties. It is imposed by the state and is generally

imbued with some public policy considerations.

• It cannot be presumed.

• Hence, the payment of taxes must be specifically

directed by our tax statutes. Also, parents and

children are obliged to support each other as

mandated by the provisions of the Family Code.

ART. 1159 - OBLIGATIONS ARISING FROM

CONTRACTS HAVE THE FORCE OF LAW

BETWEEN THE CONTRACTING PARTIES

AND SHOULD BE COMPLIED WITH IN

GOOD FAITH.

• a contract is a meeting of minds between 2 or more

persons whereby a person (or a group of persons)

binds himself, with respect to the other (or others) to

give something or to render some service.

• a contract may likewise involve mutual and reciprocal

obligations and duties between and among the parties.

• Whatever stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions

are included in a contract, as long as they are not

contrary to law, morals, good customs, public policy or

public order, such contract is the law between the

parties (Gaw v. IAC)

• Contracts which are the private laws of the

contracting parties should be fulfilled according to the

literal sense of their stipulations, if their terms are

clear and leave no room for doubt as to their intention

of the contracting parties, for contracts are obligatory,

no matter what form they may be, whenever essential

requirements for their validity are present (PAGICO v.

Mutuc)

ART. 1160 - OBLIGATIONS DERIVED FROM

QUASI-CONTRACTS SHALL BE SUBJECT TO

THE PROVISIONS OF CHAPTER 1 TITLE XVII

OF THIS BOOK.

• certain lawful, voluntary and unilateral acts give rise

to the juridical relation of quasi-contract to the end

that no one shall be unjustly enriched or benefited at

the expense of the other.

• A good example of an obligation arising from a quasi-

contract is the obligation to return what has been

obtained by mistake (solutio indebiti)

ART. 1161 - CIVIL OBLIGATIONS ARISING

FROM CRIMINAL OFFENSES SHALL BE

GOVERNED BY THE PENAL LAWS, SUBJECT

TO THE PROVISIONS OF ART 2177, AND

OF THE PERTINENT PROVISIONS OF

CHAPTER 2, PRELIMINARY TITLE, ON

HUMAN RELATIONS, AND OF TITLE XVIII

OF THIS BOOK, REGULATING DAMAGES.

• Scope of Civil Liability:

1) Restitution;

2) Reparation for the damage caused; and

3) Indemnification for consequential damages.

ART. 1162 - OBLIGATIONS DERIVED FROM

QUASI-DELICTS SHALL BE GOVERNED BY

THE PROVISIONS OF CHAPTER 2, TITLE

XVII OF THIS BOOK AND BY SPECIAL LAWS.

• quasi-delict: whoever by act or omission causes damage

to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to

pay for the damage done. Such fault, if there is no pre-

existing contractual relation between the parties, is

called quasi-delict.

ART. 1163 - EVERY PERSON OBLIGED TO

GIVE SOMETHING IS ALSO OBLIGED TO

TAKE CARE OF IT WITH THE PROPER

DILIGENCE OF A GOOD FATHER OF A

FAMILY, UNLESS THE LAW OR THE

STIPULATION OF THE PARTIES REQUIRES

ANOTHER STANDARD OF CARE.

• this article involves the prestation “to give.” The word

“something” connotes a determinate object which is

definite, known, and has already been distinctly decided

and particularly specified as the matter to be given from

among the same things belonging to the same kind.

• “diligence of a good father of a family” because it is a

commonly-accepted notion that a father will always do

everything to take care of his concerns.

• If the law does not state the diligence which is supposed to

be observed in the performance of an obligation, that

which is expected of a good father of a family is required.

• In case of a contrary stipulation of the parties, such

stipulation is should not be one contemplating a

relinquishment or waiver of the most ordinary diligence.

• An example where the law requires another standard of

care is that which involves common carriers (persons or

firms engaged in the business of carrying, transporting

passengers or goods of both, by land, water, air for

compensation, offering their service to the public)-

they are bound to observe extraordinary diligence

ART. 1164 - THE CREDITOR HAS THE

RIGHTS TO THE FRUITS OF THE THING

FROM THE TIME THE OBLIGATION TO

DELIVER IT ARISES. HOWEVER, HE

SHALL ACQUIRE NO REAL RIGHT OIVER

IT UNTIL THE SAME HAS BEEN

DELIVERED TO HIM.

• after the right to deliver the object of the prestation has

arisen in favor of the creditor but prior to the delivery of

the same, there is no real right enforceable or binding

against the whole over the object and its fruits in favor

of the person to whom the same should be given.

• The acquisition of a real right means that such right can

be enforceable against the whole world and will

prejudice anybody claiming the same object of the

prestation.

• The real right only accrues when the thing or object of

the prestation is delivered to the creditor.

• He only has a personal right over the same if it is

enforceable only against the debtor who is under an

obligation to give. This means that the personal right

of the creditor can be defeated by a third party in good

faith who has innocently acquired the property prior

to the scheduled delivery regardless of whether or not

such third party acquired the property after the right

to the delivery of the thing has accrued in favor of the

creditor. In this case, however, the aggrieved creditor

can go against the debtor for damages as the debtor

should have known that the fruits should have been

delivered to the creditor alone.

ART. 1165 - WHEN WHAT IS TO BE

DELIVERED IS A DETERMINATE THING,

THE CREDITOR, IN ADDITION TO THE

RIGHT GRANTED HIM BY ART 1170, MAY

COMPEL THE DEBTOR TO MAKE DELIVERY.

IF THE THING IS INDETERMINATE OR

GENERIC, HE MAY ASK THAT THE

OBLIGATION BE COMPLIED WITH AT THE

EXPENSE OF THE DEBTOR.

IF THE OBLIGOR DELAYS, OR HAS PROMISED

TO

DELIVER THE SAME THING TO TWO OR

MORE PERSONS WHO DO NOT HAVE THE

SAME INTEREST, HE SHALL BE

REPSONSIBLE FOR FORTUITOUS EVENT

UNTIL HE HAS EFFECTED DELIVERY.

• In the event that there is non-delivery of a generic

thing, the creditor may have it accomplished or

delivered in any reasonable and legal way charging all

expenses in connection with such fulfillment to the

debtor. The same creditor can ask a third party to

deliver the same thing of the same kind with all the

expense charged to the debtor.

• In case of non-delivery of a determinable thing, the

remedy is to file an action to compel the debtor to make

the delivery. This action is called specific performance.

• If the debtor is guilty of fraud, negligence, delay or

contravention in the performance of the obligation, the

creditor can likewise seek damages against the debtor.

• A fortuitous event – is an event which could not be

foreseen, or which though foreseen, were inevitable.

• The last paragraph of art 1165 however provides that a

fortuitous event will not excuse the obligor from his

obligation in 2 cases namely: 1) if the obligor delays; and

2) if he has promised to deliver the same thing to 2 or

more persons who do not have the same interest. In

both cases, the obligor will be liable for damages or will

be bound to replace the lost object of the prestation in

cases when the obligee agrees to the replacement.

ART. 1166 - THE OBLIGATION TO GIVE A

DETERMINATE THING INCLUDES THAT OF

DELIVERING ALL ITS ACCESSIONS AND

ACCESSORIES, EVEN THOUGH THEY MAY

NOT HAVE BEEN MENTIONED.

• Accessions are the fruits of a thing or additions to or

improvements upon a thing – the principal (ex. House

or trees on a land; rents of a building; air-conditioner

in a car; profits or dividends accruing from shares of

stocks)

• Accessories are things joined to or included with the

principal thing for the latter’s embellishment, better

use, or completion. (ex. Key of a house; frame of a

picture; bracelet of a watch machinery; bow of a

violin)

• Accessions are not necessary to the principal thing,

but the accessory and the principal thing must go

together.

ART. 1167 - IF THE PERSON OBLIGED TO

DO SOMETHING FAILS TO DO IT, THE

SAME SHALL BE EXECUTED AT HIS COST.

THIS SAME RULE SHALL BE OBSERVED IF

HE DOES IT IN CONTRAVENTION OF THE

TENOR OF THE OBLIGATION.

FURTHERMORE, IT MAY BE DECREED

THAT WHAT HAS BEEN POORLY DONE

BE UNDONE.

ART. 1168 - WHEN THE OBLIGATION

CONSISTS IN NOT DOING, AND THE

OBLIGOR DOES WHAT HAS BEEN

FORBIDDEN HIM, IT SHALL ALSO BE

UNDONE AT HIS EXPENSE.

• the debtor can ask any third person to perform the

obligation due from the debtor should the latter fail to

do the same.

• The debtor will be liable for all the expenses in

connection with the performance or fulfillment of the

obligation undertaken by the third person.

• The words “at his cost” imply both the right to have

somebody else perform the obligation and the right to

charge the expenses thereof to the debtor.

• With respect to the situation wherein the debtor

poorly undertook the obligation, the creditor has the

right to have everything be undone at the expense of

the debtor. The reason for this rule is to prevent the

debtor from taking his obligation lightly.

• In case the prestation is for the debtor not to do a

particular act or service and he nevertheless performs

it, it shall likewise be undone at his own expense.

• In Chaves v. Gonzales, the Supreme Court ruled that the

original repairer can be held liable not only for the missing

parts but also for the cost of the execution of the obligation

for repairing the typewriter by another company.

ART. 1169 - THOSE OBLIGED TO DELIVER

OR TO DO SOMETHING INCUR IN DELAY

FROM THE TIME THE OBLIGEE

JUDICIALLY OR EXTRAJUDICIALLY

DEMANDS FROM THEM THE

FULFILLMENT OF THEIR OBLIGATION.

HOWEVER, THE DEMAND BY THE

CREDITOR SHALL NOT BE NECESSARY IN

ORDER

THAT DELAY MAY EXIST:

1) WHEN THE OBLIGATION OR THE LAW

EXPRESSLY SO DECLARES; OR

2) WHEN FROM THE NATURE AND

CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE OBLIGATION IT

APPEARS THAT THE DESIGNATION OF THE TIME

WHEN THE THING IS TO BE DELIVERED OR THE

SERVICE IS TO BE RENDERED WAS A

CONTROLLING MOTIVE FOR THE

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE CONTRACT; OR

3) WHEN DEMAND WOULD BE USELESS, AS

WHEN THE OBLIGOR HAS RENDERED IT BEYOND

HIS POWER TO PERFORM

IN RECIPROCAL OBLIGATIONS, NEITHER

PARTY INCURS IN DELAY IF THE OTHER

DOES NOT COMPLY OR IS NOT READY TO

COMPLY IN A PROPER MANNER WITH

WHAT IS INCUMBENT UPON HIM. FROM

THE MOMENT ONE OF THE PARTIES

FULFILLS HIS OBLIGATION, DELAY BY THE

OTHER BEGINS.

• Delay or default can be committed by the debtor in which

case it is known as mora solvendi.

• If it is committed by the creditor, it is known as mora

accipiendi.

• Delay in the performance of the obligation, however,

must be either malicious or negligent. Hence, if the

delay was only due to inadvertence without any malice

or negligence, the obligor will no be held liable under

Art 1170.

• Default generally begins from the moment the creditor

demands the performance of the obligation. Without

such demand, judicial or extra-judicial, the effects of

default will not arise.

• Commencement of suit is a sufficient demand.

• Art 1169 is only applicable when the obligation is to do

something other than the payment of money (Picson v.

Picson).

• If the contract involving a sum of money does not

stipulate any interest and/or the time when it will be

counted, interest will run only from the time of

judicial or extra-judicial demand.

• However, damages or interest shall start to run only

after judicial or extra-judicial demand. Hence, if the

obligation were due on March 1, 2011, the aggrieved

party can file suit for specific performance

immediately after March 1, 2011. If extra-judicial

demand however was made on March 5, 2011,

damages shall be counted not from March 1, 1998 but

from March 5, 2011.

• The 2 cases where an extra-judicial demand

should first be made prior to the filing of a civil

suit are: ejectment cases and consignment cases.

If there is no extra-judicial demand made prior to the

filing of the civil suit, the ejectment case will be

dismissed. In consignment cases, the debtor must first

make an extra-judicial demand for the creditor to

accept payment of the obligation. If the creditor

unjustifiably refuses to accept payment, the debtor

can now consign the amount in court for purposes of

extinguishing the obligation.

• Demand not necessary in 3 cases: 1) when the

obligation or the law expressly so declares (ex.

Promissory note providing for payment on a particular

date without necessity of demand; Also the law

expressly declares that taxes should be paid on a

particular date); 2) when time is of the essence in a

particular contract (ex. Stock market transactions;

delivery for a one-day car exhibit); 3) when it would be

useless, as when the obligor has rendered it beyond his

power to perform (ex. A debtor promised to constitute

his house as a collateral for a particular loan which is

payable at a particular date but before he can make the

mortgage, he donates the house to his friend, demand

from the creditor to constitute the house as a collateral is

useless. In this case, his obligation becomes immediately

demandable considering that he loses his right to the

period within which to pay the loan).

• Reciprocal obligations are those created and

established at the same time, out of the same cause

and which results in a mutual relationship of creditor

and debtor between parties. In reciprocal obligations,

the performance of one is conditioned upon the

simultaneous fulfillment of the other.

ART. 1170 - THOSE WHO IN THE

PERFORMANCE OF THEIR OBLIGATIONS

ARE GUILTY OF FRAUD, NEGLIGENCE, OR

DELAY, AND THOSE WHO IN ANY MANNER

CONTRAVENE THE TENOR THEREOF, ARE

LIABLE FOR DAMAGES.

• The law specifically provides that damages can be

awarded to any person who may have been prejudiced in

the performance of the obligation as a result of fraud,

negligence, delay or contravention of the tenor of the

obligation.

• Significantly, if any of these 4 bases of liability co-exist

with a fortuitous event or aggravates the loss caused

by a fortuitous event, the obligor cannot be excused

from being liable on his obligation.

ART. 1171 - RESPONSIBILITY ARISING

FROM FRAUD IS DEMANDABLE IN ALL

OBLIGATIONS. ANY WAIVER OF AN

ACTION FOR FUTURE FRAUD IS VOID.

• When a party complies with or performs his

obligation fraudulently, he is liable for damages.

• If, in the contract of sale, A and B stipulated that any

fraudulent act by another in the performance of his

obligation shall not be a ground for the aggrieved party

to file a suit against the other for fraud is a void

stipulation. By express provision of law, such waiver is

void.

• The dolo or fraud which is committed to induce a party

to enter into a contract, thereby making the agreement

annullable is not the one contemplated by Art 1171.

• The dolo or fraud under Art 1171 necessarily involves a

valid agreement but, in the performance of the same,

fraud is committed.

ART. 1172 - RESPONSIBILITY ARISING

FROM NEGLIGENCE IN THE

PERFORMANCE OF EVERY KIND OF

OBLIGATION IS ALSO DEMANDABLE, BUT

SUCH LIABILITY MAY BE REGULATED BY

THE COURTS, ACCORDING TO THE

CIRCUMSTANCES.

• Kinds of Negligence according to source of obligation:

1) Contractual Negligence (culpa contractual),

negligence in contracts resulting in their breach. This

kind of negligence is not a source of obligation, it

merely makes the debtor liable for damages in view

of his negligence in the fulfillment of a pre-existing

obligation.

2) Civil Negligence (culpa Aquiliana), negligence

which by itself is the source of an obligation

between the parties not so related before any pre-

existing contract. It is also called tort or quasi-delict.

3) Criminal Negligence (culpa criminal), negligence

resulting in the commission of a crime, the same

negligent act causing damages may produce civil

liability arising from a crime under Art. 100 of the

RPC, or create an action for quasi-delict under Art.

2176 of the Civil Code.

ART. 1173 - THE FAULT OR NEGLIGENCE OF

THE OBLIGOR CONSISTS IN THE

OMISSION OF THAT DILIGENCE WHICH IS

REQUIRED BY THE NATURE OF THE

OBLIGATION AND CORRESPONDS WITH

THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE PERSONS,

OF THE TIME AND THE PLACE. WHEN

NEGLIGENCE SHOWS BAD FAITH, THE

PROVISIONS OF ARTICLES 1171 AND

2201, PARAGRAPH 2, SHALL APPLY.

IF THE LAW OR CONTRACT DOES NOT

STATE THE DILIGENCE WHICH IS TO BE

OBSERVED IN

THE PERFORMANCE, THAT WHICH IS

EXPECTED OF A GOOD FATHER OF A

FAMILY SHALL BE REQUIRED.

• In essence, negligence is that want of care required by

the circumstances.

• As a general rule, negligence must be proven.

• In Syquia v. CA, the law defines negligence as the

“omission of that diligence which is required by the

nature of the obligation and corresponds with the

circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the

place.” In the absence of stipulation or legal

provision providing the contrary, the diligence to be

observed in the performance of the obligation is that

which is expected of a good father of a family.

• In PNB v. CA, where the bank negligently dishonored

the check of its depositor, the SC said, “This court has

ruled that a bank is under the obligation to treat the

accounts of its depositors with meticulous care

whether such account consists only of a few hundred

pesos or of millions of pesos. Responsibility arising

from negligence in the performance of every kind of

obligation is demandable. While petitioner’s

negligence in this case may not have been attended

with malice and bad faith, nevertheless, it caused

serious anxiety, embarrassment and humiliation to

private respondent for which she is entitled to recover

reasonable moral damages.

• The law likewise provides that when negligence

shows bad faith, the provisions of Articles 1171 and

2201, par 2 shall apply.

• In Samson v. CA, the SC discussing bad faith said: “Bad

faith is essentially a state of mind affirmatively

operating with furtive design or with some motive of

ill-will. It does not simply connote bad judgment or

negligence. It imports a dishonest purpose or some

moral obliquity and conscious doing of wrong. Bad

faith is thus synonymous with fraud and involves a

design to mislead or deceive another, not prompted by

an honest mistake as to one’s rights or duties, but by

some interested or sinister motive.”

• Pursuant to Art 2201, par 2, the obligor shall be

responsible for all damages which may be reasonably

attributed to the non-performance of the obligation.

ART. 1174 - EXCEPT IN CASES EXPRESSLY

SPECIFIED BY THE LAW, OR WHEN IT IS

OTHERWISE DECLARED BY STIPULATION,

OR WHEN THE NATURE OF THE

OBLIGATION REQUIRES THE ASSUMPTION

OF RISK, NO PERSON SHALL BE

RESPONSIBLE FOR THOSE EVENTS WHICH,

COULD NOT BE FORESEEN, OR WHICH,

THOUGH FORESEEN, WERE INEVITABLE.

• The general rule is that “no one should be held to account

for fortuitous cases” which are those situations that could

not be foreseen, or which though foreseen,

were inevitable. An act of God has been defined as an

accident, due directly and exclusively to natural

causes without human intervention, which by no

amount of foresight, pains or care, reasonably to have

expected, could have been prevented.

• In Nakpil v. CA, the SC said, “To exempt the obligor

from liability under Art 1174 of the Civil Code, for a

breach of an obligation due to an “act of God,” the ff.

must concur: a) the cause of the breach of the

obligation must be independent of the will of the

debtor;

b) the event must either be unforeseeable or

unavoidable; c) the event must be such as to render it

impossible for the debtor to fulfill his obligation in a

normal manner; and d) the debtor must be free from

any participation in, or aggravation of the injury.

Thus, it has been held that when the negligence of a

person concurs with an act of God in producing a loss,

such person is not exempt from liability by showing

that the immediate cause of the damage was the act of

God. To be exempt from liability for loss because of an

act of God, he must be free from any previous

negligence or misconduct by which that loss or

damage may have been occasioned.”

• In Sia v. CA, where the bank failed to notify its client of

the flooding of its safety deposit box containing the

said client’s valuable stamp collection resulting in the

destruction of the said collection, and where the said

bank already had two previous experiences of the

flooding of the said safety deposit box located inside

the bank that was guarded 24 hrs a day, the SC

reversed the ruling of the CA in not holding the bank

for damages on the basis of fortuitous event and held

that the bank was negligent.

• In Dioquino v. Laureano, the SC considered the sudden

and unexpected throwing of stone directed at the

car of the plaintiff causing damage to the said car a

fortuitous event.

• When the object of the prestation is generic, like the

payment of a sum of money as a consequence of a loan

contract, the debtor cannot avail of the benefit of a

fortuitous event even if the object for which the

loaned money is used, such as the construction of a

factory, is wiped out by a typhoon. Also, even if there

is a fortuitous event, a person can still be held

responsible for the performance of his obligation if the

law, or the stipulation of the parties, or when the

nature of the obligation so requires.

• The law can provide that, even if there is a fortuitous

event, the obligor can still liable. An example of this is

par. 3 of Art 1165 which provides that if the obligor

delays, or has promised to deliver the same thing to two

or more persons who do not have the same interest, he

shall be responsible for any fortuitous event until he has

effected delivery. Also Art 1268 provides that when the

debt of a thing certain and determinate proceeds from a

criminal offense, the debtor shall not be exempted from

the payment of its price, whatever may be the cause for

the loss, unless the thing having been offered by him to

the person who should receive it, the latter refused

without justification to accept it.

• When the parties declare that they shall be liable

even for loss due to a fortuitous event, they shall

be so liable.

• When the nature of the obligation requires the

assumption of risk, the person obliged to perform the

obligation shall likewise not be excused should a

fortuitous event occur.

ART. 1175 - USURIOUS TRANSACTIONS

SHALL BE GOVERNED BY SPECIAL LAWS.

• Usury is contracting for or receiving interest in excess of

the amount allowed by law for the loan or use of money,

goods, chattels or credit (Tolentino vs. Gonzales)

• Requisites for recovery of Interest:

1) The payment of interest must be expressly stipulated;

2) The agreement must be in writing; and

3) The interest must be lawful.

• A stipulation for the payment of usurious interest is void,

that is, as if there is no stipulation as to interest.

ART. 1176 - THE RECEIPT OF THE PRINCIPAL

BY THE CREDITOR, WITHOUT

RESERVATION WITH RESPECT TO THE

INTEREST, SHALL GIVE RISE TO THE

PRESUMPTION THAT SAID INTEREST HAS

BEEN PAID.

THE RECEIPT OF A LATER INSTALLMENT OF

A DEBT WITHOUT RESERVATION AS TO

PRIOR INSTALLMENTS, SHALL LIKEWISE

RAISE THE PRESUMPTION THAT SUCH

INSTALLMENTS HAVE BEEN PAID.

• Presumption is the inference of a fact not actually

known arising from its usual connection with another

which is known.

• Two kinds of Presumption:

1) Conclusive Presumption – one which cannot be

contradicted, like the presumption that everyone is

conclusively presumed to know the law; and

2) Disputable (or rebuttable) Presumption – one

which can be contradicted or rebutted by presenting

proof to the contrary, like the presumption

established in Art. 1176.

ART. 1177 - THE CREDITORS, AFTER

HAVING PURSUED THE PROPERTY IN

THE POSSESSION OF THE DEBTOR TO

SATISFY THEIR CLAIMS, MAY EXERCISE

ALL THE RIGHTS AND BRING ALL THE

ACTIONS OF THE LATTER FOR THE SAME

PURPOSE, SAVE THOSE WHICH ARE

INHERENT IN HIS PERSON; THEY MAY

ALSO IMPUGN THE ACTS WHICH THE

DEBTOR MAY HAVE DONE TO DEFRAUD

THEM.

• The law protects the creditors. The creditor is given

by law all possible remedies to enforce such

obligations.

• The ff. successive measures must be taken by a

creditor before he may bring an action for rescission

of an allegedly fraudulent sale: 1) exhaust the

properties of the debtor through levying by

attachment and execution upon all the property of the

debtor, except such as are exempt by law from

execution; 2) exercise all the rights and actions of the

debtor, save those personal to him (accion subrogata);

and 3) seek rescission of the contracts executed by the

debtor in fraud of their rights (accion pauliana).

• In Adorable v. CA, it was held that unless a debtor

acted in fraud of his creditor, the creditor has no right

to rescind a sale made by the debtor to someone on

the mere ground that such sale will prejudice the

creditor’s rights in collecting later on from the debtor.

The creditor’s right against the debtor is only a

personal right to receive payment for the loan; it is not

a real right over the lot subject of the deed of sale

transferring the debtor’s property.

ART. 1178 - SUBJECT TO THE LAWS, ALL

RIGHTS ACQUIRED IN VIRTUE OF AN

OBLIGATION ARE TRANSMISSIBLE, IF

THERE HAS BEEN NO STIPULATION TO

THE CONTRARY.

• However, the person who transmits the right cannot

transfer greater rights than he himself has by virtue of

the obligation. Conversely, the person to whom the

rights are transmitted can have no greater interest than

that possessed by the transmitter at the time of

transmission of the rights.

• The transmissibility of rights may be limited, or

altogether prohibited by stipulation of the parties.

Thus, it can be stipulated in a contract that the

assignment of any or all the rights provided by such

contract is prohibited.

• Likewise, no transmission can be made of a particular

right if the personal qualifications or circumstances of

the transferor is a material ingredient attendant in the

obligation. Hence, an author who specializes in horror

stories written in a very distinct and peculiar style and

who has been engaged by a publisher to write his (the

author’s) kind of horror stories for his magazine cannot

transmit his rights arising from such obligation to

anybody else.

• Transmission must likewise be subject to pertinent laws.

SOURCES:

1)OBLIGATIONS and CONTRACTS (Text and Cases) of

STA. MARIA (2006 Edition)

2)The LAW on OBLIGATIONS and CONTRACTS of

Hector S. De Leon (2003 Edition)

BY: Benchie B. Gonzales

You might also like

- Lecture Notes 01Document3 pagesLecture Notes 01KentNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 Arts. 1163 1178Document70 pagesCHAPTER 2 Arts. 1163 1178Sergio ConjugalNo ratings yet

- Improving Cash Flow Using Credit ManagementDocument25 pagesImproving Cash Flow Using Credit ManagementSharath RajarshiNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 1231: NOTE TO SELF Remember To Reread Examples in BookDocument13 pagesARTICLE 1231: NOTE TO SELF Remember To Reread Examples in BookJa Dueñas100% (3)

- Obligation and Contracts Art 1156 To 1178 Civil Code of The Philippines - Republic Act No 386Document3 pagesObligation and Contracts Art 1156 To 1178 Civil Code of The Philippines - Republic Act No 386Mom Gie100% (7)

- Sample PPMDocument70 pagesSample PPMalvah100% (3)

- Article 1320-1340Document80 pagesArticle 1320-1340jonathan parba75% (4)

- Obligations AND Contracts: ARTS 1232-1242Document24 pagesObligations AND Contracts: ARTS 1232-1242Britney Kim100% (1)

- CHAPTER I General ProvisionsDocument42 pagesCHAPTER I General Provisionstintin plata100% (1)

- Article 1243-1253Document6 pagesArticle 1243-1253Estoryahe'ng HeartNo ratings yet

- Article 1239Document6 pagesArticle 1239Kang Minhee100% (1)

- Obligation, Right, and Wrong (Cause of Action) DistinguishedDocument9 pagesObligation, Right, and Wrong (Cause of Action) DistinguishedMargaveth P. BalbinNo ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Accounting 4Th Edition Pearl Tan Full ChapterDocument61 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting 4Th Edition Pearl Tan Full Chapterwilliam.rainey525100% (18)

- Judge Pimentel Crim Transcript - Book 2Document65 pagesJudge Pimentel Crim Transcript - Book 2Benchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Module Number 1: Obligations and ContractsDocument5 pagesModule Number 1: Obligations and ContractsClarito Lopez0% (1)

- ACTIVITY2Document4 pagesACTIVITY2shara santosNo ratings yet

- Obligations Reviewer 1156-1192Document24 pagesObligations Reviewer 1156-1192ALINASSER YUSOPNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Nature and Effect ObligationsDocument74 pagesChapter 2 - Nature and Effect ObligationsTanya KimNo ratings yet

- Module 4 - Nature and Effect of Obligations PDFDocument65 pagesModule 4 - Nature and Effect of Obligations PDFKobe MartinezNo ratings yet

- Sample Contract Full Time or Part TimeDocument3 pagesSample Contract Full Time or Part TimeBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Article 1305 - 1318Document2 pagesArticle 1305 - 1318Giana JeanNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts (Chapter 2)Document13 pagesObligations and Contracts (Chapter 2)Leesh67% (3)

- Articles 1246, 1247, 1248, 1249Document9 pagesArticles 1246, 1247, 1248, 1249Kang MinheeNo ratings yet

- Loan Agreement With Chattel Mortgage: 34 M.J. Cuenco Ave., Cebu CityDocument6 pagesLoan Agreement With Chattel Mortgage: 34 M.J. Cuenco Ave., Cebu CityManny DerainNo ratings yet

- Section 5 CompensationDocument29 pagesSection 5 CompensationKang Minhee100% (1)

- Kinds of Conditions LectureDocument48 pagesKinds of Conditions LectureKristine Coma50% (2)

- Requisites of Mora SolvendiDocument4 pagesRequisites of Mora SolvendiRoyce HernandezNo ratings yet

- Article 1181-1182Document11 pagesArticle 1181-1182Belle100% (12)

- Oblicon Midterm Exam 1Document25 pagesOblicon Midterm Exam 1Dark Princess ShadowNo ratings yet

- 1156 1178Document8 pages1156 1178Trisha Cabral100% (5)

- Nature and Effect of Obligations Article 1168-1169Document4 pagesNature and Effect of Obligations Article 1168-1169Jotham Del Rosario CansinoNo ratings yet

- Holding Deposit AgreementDocument1 pageHolding Deposit AgreementBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 1181 - 1190 Pure and Conditional ObligationsDocument11 pages1181 - 1190 Pure and Conditional ObligationsscfsdNo ratings yet

- Natural ObligationDocument10 pagesNatural ObligationJeane Mae Boo100% (1)

- Article 1284 & 1285Document12 pagesArticle 1284 & 1285Joneric Ramos100% (1)

- Philippine Oblicon Articles 1231-1260Document22 pagesPhilippine Oblicon Articles 1231-1260Danielle Alessandra T. Calpo100% (1)

- Classifications of ObligationsDocument1 pageClassifications of ObligationsMark WatneyNo ratings yet

- Article 1341-1355 ObliconDocument2 pagesArticle 1341-1355 Obliconporeoticsarmy0% (1)

- Law Contents 1156 1200Document25 pagesLaw Contents 1156 1200Crumwell MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Oblicon QUIZ 2 Reviewer Article 1207-1304Document20 pagesOblicon QUIZ 2 Reviewer Article 1207-1304Ricca Resula100% (1)

- Chapter 3, Oblicon ReviewerDocument7 pagesChapter 3, Oblicon Reviewerjaine030586% (7)

- Chapter 3, Sec.4: Joint and Solidary ObligationsDocument3 pagesChapter 3, Sec.4: Joint and Solidary ObligationsPrinces Emerald ErniNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 1163 To 1165Document7 pagesARTICLE 1163 To 1165JSPAMoreNo ratings yet

- Report 1217-1227Document3 pagesReport 1217-1227Donato Galleon IIINo ratings yet

- Business LawDocument10 pagesBusiness LawGier FullonNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE 1158 To 1162Document9 pagesARTICLE 1158 To 1162JSPAMoreNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2-ObliconDocument14 pagesLesson 2-ObliconDrew BanlutaNo ratings yet

- Article 1164-1178Document18 pagesArticle 1164-1178Shaina SamonteNo ratings yet

- Effects of Obligation: Accessory ObligationsDocument2 pagesEffects of Obligation: Accessory ObligationsAndrea EllisNo ratings yet

- Art 1175Document3 pagesArt 1175Kc FernandezNo ratings yet

- Notes ObliconDocument4 pagesNotes ObliconDino Abiera100% (1)

- Lecture Notes Art 1262 To 1277Document10 pagesLecture Notes Art 1262 To 1277Shiela RengelNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 To 3.1Document19 pagesChapter 1 To 3.1Nica MontevirgenNo ratings yet

- Sample Problems With Suggested Answers 2Document9 pagesSample Problems With Suggested Answers 2AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Obligations: Juridical Necessity Means That The Court May Be Asked To Order The Performance of AnDocument8 pagesObligations: Juridical Necessity Means That The Court May Be Asked To Order The Performance of AnKim YriganNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts Chapter 2 - Nature and Effects of Obligations ARTICLE 1165Document1 pageObligations and Contracts Chapter 2 - Nature and Effects of Obligations ARTICLE 1165Oh Seluring100% (1)

- Article 1196Document17 pagesArticle 1196Christlyn Joy BaralNo ratings yet

- Assignment #5Document4 pagesAssignment #5Lenmariel GallegoNo ratings yet

- Article 1400-1420Document10 pagesArticle 1400-1420Princess Anne RicafortNo ratings yet

- Canonizado V Benitez PDFDocument4 pagesCanonizado V Benitez PDFYet Barreda Basbas100% (1)

- EffectofObligations PDFDocument0 pagesEffectofObligations PDFÄnne Ü KimberlieNo ratings yet

- Article 1330Document9 pagesArticle 1330Liyana ChuaNo ratings yet

- OBLICON - Chapter 1 ProblemDocument1 pageOBLICON - Chapter 1 ProblemArahNo ratings yet

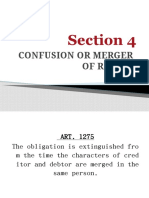

- Confusion or Merger of Rights: Section 4Document17 pagesConfusion or Merger of Rights: Section 4Rowena Shaira AbellarNo ratings yet

- Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoDocument46 pagesArt. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- RFBT 1 Obli Chap 1 To Chap 3 Section 2Document16 pagesRFBT 1 Obli Chap 1 To Chap 3 Section 2S haNo ratings yet

- OBLIDocument4 pagesOBLIejej667788No ratings yet

- Eucharistic Miracle in Lanciano ItalyDocument4 pagesEucharistic Miracle in Lanciano ItalyBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Group Report - Guidelines FormatDocument1 pageGroup Report - Guidelines FormatBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Atty. Dennis v. Nino Vs Justice Normandie B. PizarroDocument8 pagesAtty. Dennis v. Nino Vs Justice Normandie B. PizarroBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Cecilia Gadrinab Senarlo Vs Judge Maximo G.W. PaderangaDocument8 pagesCecilia Gadrinab Senarlo Vs Judge Maximo G.W. PaderangaBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- The Red Eye: Reganit, Chelsea Marie ADocument28 pagesThe Red Eye: Reganit, Chelsea Marie ABenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- CFC Chapter 4Document15 pagesCFC Chapter 4Benchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Receiving FormDocument1 pageReceiving FormBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Contract of Transport by SeaDocument7 pagesContract of Transport by SeaBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Art. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoDocument46 pagesArt. 1156 - An Obligation Is A: Juridical Necessity To Give, To Do or Not To DoBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Hand GunsDocument14 pagesHand GunsBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Oblicon ArtsDocument26 pagesOblicon ArtsBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- TaurusDocument9 pagesTaurusBenchie B. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 16 CA Final SFM Mafa Formula Booklet by Aaditya Jain All Formula in One PlaDocument89 pages16 CA Final SFM Mafa Formula Booklet by Aaditya Jain All Formula in One Plasiddharth karli100% (1)

- Form JDocument4 pagesForm Jsbaby216No ratings yet

- Weekly FX Insight: Citibank Wealth ManagementDocument14 pagesWeekly FX Insight: Citibank Wealth Managementngdaniel13029No ratings yet

- Self Help GroupDocument60 pagesSelf Help GroupKETAN100% (1)

- ECO202-Practice Test - 22 (CH 22)Document4 pagesECO202-Practice Test - 22 (CH 22)Aly HoudrojNo ratings yet

- Ignouassignments - in 9891268050 7982987641: Assignment Solutions Guide (2021-22)Document16 pagesIgnouassignments - in 9891268050 7982987641: Assignment Solutions Guide (2021-22)Ajay KumarNo ratings yet

- Lookup and Reference Functions: Function DescriptionDocument43 pagesLookup and Reference Functions: Function Descriptionmuthuswamy77No ratings yet

- Financial Ratios Analysis of NestleDocument17 pagesFinancial Ratios Analysis of NestleAnuj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Time Value of Money - Problem & Soluation-1Document6 pagesTime Value of Money - Problem & Soluation-1Diptimoy Barua100% (1)

- Izodias Missing Millions - SFO Annual ReportDocument17 pagesIzodias Missing Millions - SFO Annual ReporthyenadogNo ratings yet

- CRB Complete ScamDocument8 pagesCRB Complete ScamOkkishoreNo ratings yet

- Self Regulating EconomyDocument17 pagesSelf Regulating EconomyOsmaan GóÑÍNo ratings yet

- The Management of Working CapitalDocument16 pagesThe Management of Working Capitalsalehin1969No ratings yet

- Direction: Provide The Step-By-Step Solutions To The Following Problems. (5 Items X 5 Points)Document3 pagesDirection: Provide The Step-By-Step Solutions To The Following Problems. (5 Items X 5 Points)Monique BalteNo ratings yet

- Business CyclesDocument194 pagesBusiness CyclesEugenio MartinezNo ratings yet

- Compre Assignment #1 - For SendingDocument9 pagesCompre Assignment #1 - For SendingmymyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Bond Analysis PDFDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Bond Analysis PDFakhi pranavNo ratings yet

- Invb 6572Document24 pagesInvb 6572Temp RoryNo ratings yet

- Financial Management: Manish SirDocument94 pagesFinancial Management: Manish SirHarmanjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Quiz Gen Math - AnnuitiesDocument1 pageQuiz Gen Math - AnnuitiesFrancez Anne Guanzon0% (2)

- Ps1 AnswerDocument6 pagesPs1 AnswerChan Kong Yan AnnieNo ratings yet

- Return On Assets-ROA DefinitionDocument10 pagesReturn On Assets-ROA DefinitionChristine DavidNo ratings yet

- En Le Havre RulesDocument16 pagesEn Le Havre RulesCaio MellisNo ratings yet

- 02 Country Bankers Insurance Corporation vs. Lianga Bay and Community Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc.Document16 pages02 Country Bankers Insurance Corporation vs. Lianga Bay and Community Multi-Purpose Cooperative, Inc.ATR100% (1)

- Saccos and Youth DevelopmentDocument29 pagesSaccos and Youth DevelopmentGgayi Joseph0% (1)

- Idaho FRSDocument79 pagesIdaho FRSMatt BrownNo ratings yet