Professional Documents

Culture Documents

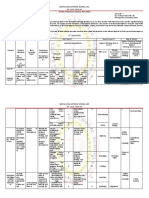

Mental Status Examination (MSE)

Uploaded by

Pia Mae Buaya100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

180 views13 pagesThe Mental Status Examination (MSE) is a structured assessment of a client's cognitive and behavioral functioning used to evaluate mental health conditions. The MSE assesses appearance, mood, affect, speech, thought processes, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, knowledge, judgment, and insight. It generates crucial information for treatment planning and can be administered quickly in various clinical settings. Key elements include behavior, emotions, speech, thoughts, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, and knowledge/insights/judgment.

Original Description:

Original Title

MSE_PDF (1)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Mental Status Examination (MSE) is a structured assessment of a client's cognitive and behavioral functioning used to evaluate mental health conditions. The MSE assesses appearance, mood, affect, speech, thought processes, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, knowledge, judgment, and insight. It generates crucial information for treatment planning and can be administered quickly in various clinical settings. Key elements include behavior, emotions, speech, thoughts, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, and knowledge/insights/judgment.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

180 views13 pagesMental Status Examination (MSE)

Uploaded by

Pia Mae BuayaThe Mental Status Examination (MSE) is a structured assessment of a client's cognitive and behavioral functioning used to evaluate mental health conditions. The MSE assesses appearance, mood, affect, speech, thought processes, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, knowledge, judgment, and insight. It generates crucial information for treatment planning and can be administered quickly in various clinical settings. Key elements include behavior, emotions, speech, thoughts, perceptions, impulse control, cognition, and knowledge/insights/judgment.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 13

Mental Status Examination (MSE)

The Mental Status Examination (MSE)

- a structured assessment of client’s behavioural and cognitive functioning

- is a vital component of nursing care that assists with evaluation of mental

health conditions.

- The MSE is analogous to the physical examination and is used to evaluate an

individual’s current cogitative, affective and behavioural functioning

- Specifically, the MSE assesses a client’s current state including general

appearance, mood and affect, speech, thought process and content,

perceptual disturbances, impulse control, cognition, knowledge,

judgment and insight

- The MSE can be used across clinical settings, not just in a psychiatric

context, takes only a few minutes to administer and can generate

information that is crucial for creating a plan of care

MSE Elements

The acronym BEST PICK can assist with learning the main

elements of an MSE

• Behavior and general appearance

• Emotions

• Speech

• Thought content and processes

• Perceptual disturbances

• Impulse control

• Cognition

• Knowledge, insights and judgment

Behaviour and general appearance

• age, sex, gender, cultural background, posture, dress/ grooming,

manner, alertness, as well as agitation, hyperactivity, psychomotor

retardation, unusual movements, catatonia, etc.

• These variables give the examiner an overall impression of the patient.

The patient's physical appearance (apparent vs. stated age), grooming

(immaculate/unkempt), dress (subdued/riotous), posture

(erect/kyphotic), and eye contact (direct/furtive) are all pertinent

observations. Certain specific syndromes such as unilateral spatial

neglect and the disinhibited behavior of the frontal lobe syndrome are

readily appreciated through observation of behavior.

Emotions (Mood and Affect)

• Affect is the patient's immediate expression of emotion; mood refers to the

more sustained emotional makeup of the patient's personality. Patients display a

range of affect that may be described as broad, restricted, labile, or flat. Affect is

inappropriate when there is no consonance between what the patient is

experiencing or describing and the emotion he is showing at the same time (e.g.,

laughing when relating the recent death of a loved one). Both affect and mood

can be described as dysphoric (depression, anxiety, guilt), euthymic (normal), or

euphoric (implying a pathologically elevated sense of well-being).

• Affect must be judged in the context of the setting and those observations that

have gone before. For example, the startled-looking patient with eyes wide open

and perspiration beading out on the forehead is soon recognized as someone

suffering from Parkinson's disease, when the paucity of motion and diminished

eye blink are noted and the beads of perspiration turn out to be seborrhea.

Speech

• rate, amount, style and tone of speech.

• Listening to spontaneous speech as the patient relates answers to open-

ended questions yields much useful information. One might discern

problems in output or articulation such as the hypophonia of Parkinson's

disease, the halting speech of the patient with word-finding difficulties, or

the rapid and pressured speech of the manic or amphetamine-intoxicated

patient.

Thought content and processes

• abnormalities, obsessions, delusions and suicidal and homicidal

thoughts and thought process as well as loose associations, tangential

thinking, word salad, and neologisms, circumstantial thought, and

concrete versus abstract thought.

• The inability to process information correctly is part of the definition of

psychotic thinking. How the patient perceives and responds to stimuli is

therefore a critical psychiatric assessment. Does the patient harbor

realistic concerns, or are these concerns elevated to the level of

irrational fear? Is the patient responding in exaggerated fashion to

actual events, or is there no discernible basis in reality for the patient's

beliefs or behavior?

Perceptual disturbances

• illusions and hallucinations.

• Patients may exhibit marked tendencies toward somatization or may be troubled

with intrusive thoughts and obsessive ideas. The more seriously ill patient may

exhibit overtly delusional thinking (a fixed, false belief not held by his cultural

peers and persisting in the face of objective contradictory

evidence), hallucinations (false sensory perceptions without real stimuli),

or illusions (misperceptions of real stimuli). Because patients often conceal these

experiences, it is well to ask leading questions, such as, "Have you ever seen or

heard things that other people could not see or hear? Have you ever seen or

heard things that later turned out not to be there?" Likewise, it is necessary to

interpret affirmative responses conservatively, as mistakenly hearing one's name

being called, or experiencing hypnagogic hallucinations in the peri-sleep period,

is within the realm of normal experience.

Impulse control

• ability to delay, modulate or inhibit expressions or behaviours.

• Overall motor activity should also be noted, including any tics or unusual

mannerisms. Slowness and loss of spontaneity in movement may characterize

a subcortical dementia or depression, while akathisia (motor restlessness) may

be the harbinger of an extrapyramidal syndrome secondary to phenothiazine

• The patient's attitude is the emotional tone displayed toward the examiner,

other individuals, or his illness. It may convey a sense of hostility, anger,

helplessness, pessimism, overdramatization, self-centeredness, or passivity.

Likewise, the patient's attitude toward the illness is an important variable. Is

the patient a help-rejecting complainer? Does the patient view the illness as

psychiatric or nonpsychiatric? Does the patient look for improvement or is he

or she resigned to suffer in silence?

Cognition

• consciousness, orientation, concentration and memory.

• Short-term memory is the most clinically pertinent, and the most important to be tested. Short-

term retention requires that the patient process and store information so that he or she can

move on to a second intellectual task and then call up the remembrance after completion of the

second task. Short-term memory may be tested by having the patient learn four unrelated

objects or concepts, a short sentence, or a five-component name and address, and then asking

the patient to recall the information in 3 to 5 minutes after performing a second, unrelated

mental task.

• Orientation largely reflects recent memory function. Questions such as, "Where are we right

now? What city are we in? What is today's date? What time is it right now (to the nearest

hour)?" are pertinent questions.

• Immediate recall can be tested once again by having the patient repeal digit spans, both

forward and backward. Long-term memory can be tested by the patient's ability to recall

remote personal or historic events (e.g., the naming of previous presidents, major wars, date of

the bombing of Pearl Harbor) or answer select questions from the WAIS information subtest.

Obviously, in asking remote personal events, the physician must be privy to accurate

information to judge the accuracy of the patient's response.

Knowledge, insights and judgment

• the capacity to identify possible courses of action, anticipate

consequences, and choose appropriate behaviour, and extent of

awareness of illness and maladaptive behaviours.

You might also like

- Hirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Examination - Bring To LectureDocument6 pagesMental Status Examination - Bring To LectureJae ChoiNo ratings yet

- Rle AssDocument5 pagesRle AssMikaCasimiroBalunanNo ratings yet

- Case 2Document8 pagesCase 2Kreshnik IdrizajNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Case StudyDocument11 pagesMental Health Case Studyapi-453449063No ratings yet

- Mental Health Nursing Case Study - CompleteDocument12 pagesMental Health Nursing Case Study - Completeapi-546486919No ratings yet

- Definition:: EpilepsyDocument7 pagesDefinition:: EpilepsyNinia MNo ratings yet

- MSE Acute PsychosisDocument4 pagesMSE Acute Psychosisilakkiya ilakkiyaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For A Patient With SchizophreniaDocument14 pagesNursing Care Plan For A Patient With SchizophreniaJerilee SoCute WattsNo ratings yet

- SCHIZODocument25 pagesSCHIZOQuinonez Anna MarieNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Social PhobiaDocument1 pageCase Study of Social PhobiaSarah KhairinaNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Mental HealthDocument9 pagesCase Study - Mental Healthapi-380891151No ratings yet

- A Case of Social PhobiaDocument3 pagesA Case of Social PhobiaFaRaz MemOnNo ratings yet

- Mental Retardation Treatment and ManagementDocument12 pagesMental Retardation Treatment and ManagementMelchoniza CalagoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan No. 1 3Document4 pagesNursing Care Plan No. 1 3Kristina ParasNo ratings yet

- Alcoholism Care PlanDocument11 pagesAlcoholism Care Planilakkiya ilakkiyaNo ratings yet

- Case Study Psychia Bipolar 2Document57 pagesCase Study Psychia Bipolar 2Joule PeirreNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Dependence SyndromeDocument6 pagesAlcohol Dependence Syndromemaakkan100% (2)

- Stages of Psychotherapy Process: Zsolt UnokaDocument15 pagesStages of Psychotherapy Process: Zsolt UnokaNeil Retiza AbayNo ratings yet

- Case PresentationDocument27 pagesCase PresentationSatya BhagathNo ratings yet

- CASE PRESENTATION PP - Anxiety. Tiffany GordonDocument6 pagesCASE PRESENTATION PP - Anxiety. Tiffany GordonTiffany GordonNo ratings yet

- Mental Status ExaminationDocument8 pagesMental Status ExaminationEmJay BalansagNo ratings yet

- Format MSEDocument3 pagesFormat MSESubir Banerjee0% (1)

- The Psychiatric Mental Status Exam (MSE)Document4 pagesThe Psychiatric Mental Status Exam (MSE)dev100% (1)

- Case Study - Mental Status ExaminationDocument5 pagesCase Study - Mental Status ExaminationSrivathsanNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Mental Status Exam: General AppearanceDocument3 pagesPediatric Mental Status Exam: General AppearanceZelel GaliNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing - Mental Status ExaminationDocument4 pagesPsychiatric Nursing - Mental Status ExaminationChien Lai R. BontuyanNo ratings yet

- Bipolar NCPDocument2 pagesBipolar NCPAngel BunolNo ratings yet

- Schizphrenia Nursing Car PlanDocument2 pagesSchizphrenia Nursing Car PlanAmjad AliNo ratings yet

- Late Adulthood: Characteristics, Developmental Tasks, Ageing and AgeismDocument12 pagesLate Adulthood: Characteristics, Developmental Tasks, Ageing and AgeismkikiNo ratings yet

- Case Study 3 (Eating Disorder)Document11 pagesCase Study 3 (Eating Disorder)Atul MishraNo ratings yet

- Recreational TherapyDocument22 pagesRecreational TherapyKishore RathoreNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument17 pagesCase Studyapi-508597583No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Study of Paranoid Schizophrenia: Submitted byDocument39 pagesComprehensive Study of Paranoid Schizophrenia: Submitted byPatricia Lingad RNNo ratings yet

- Combine Report DelhiDocument15 pagesCombine Report DelhisomaNo ratings yet

- Case No 1:-Bio DataDocument8 pagesCase No 1:-Bio DataSarah Saqib Ahmad100% (1)

- SchizophreniaDocument51 pagesSchizophreniaGino Al Ballano BorinagaNo ratings yet

- Hebephrenic SchizophreniaDocument2 pagesHebephrenic SchizophreniaJanelle Matamorosa100% (1)

- Psy. CS FDocument28 pagesPsy. CS FShreya SinhaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2 (PTSD)Document12 pagesCase Study 2 (PTSD)Atul MishraNo ratings yet

- Bpad 051822Document32 pagesBpad 051822Shubhrima KhanNo ratings yet

- 2.A Ndera CaseDocument14 pages2.A Ndera CaseNsengimana Eric MaxigyNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Comprehensive Case Study 1Document11 pagesRunning Head: Comprehensive Case Study 1api-546355462No ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing Process RecordingDocument2 pagesPsychiatric Nursing Process RecordingEunice May Saban AldaNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Examination: Identification DataDocument5 pagesMental Status Examination: Identification Datailakkiya ilakkiyaNo ratings yet

- Glasgow Coma ScaleDocument3 pagesGlasgow Coma Scaletoto11885No ratings yet

- Structured Format For History and MSEDocument22 pagesStructured Format For History and MSEfizNo ratings yet

- Final Hernioplasty Compilation RevisedDocument58 pagesFinal Hernioplasty Compilation RevisedRaidis PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Organic Mental Disorder: Presented By: Priyanka Kumari M.Sc. NursingDocument50 pagesOrganic Mental Disorder: Presented By: Priyanka Kumari M.Sc. NursingHardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Grand ReportsDocument60 pagesGrand ReportsfilchibuffNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Case PresentationDocument12 pagesPediatric Case PresentationMohammed jouhra100% (1)

- Case StudyDocument10 pagesCase StudyDharitri HaloiNo ratings yet

- Refractive ErrorDocument6 pagesRefractive Errortri erdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation - 1Document19 pagesCase Presentation - 1GERA SUMANTHNo ratings yet

- PR 1Document3 pagesPR 1Hardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- King's TheoryDocument13 pagesKing's Theorylatasha deshmukhNo ratings yet

- CDNCPDocument2 pagesCDNCPGooph BusterNo ratings yet

- Mental Status EvaluationDocument7 pagesMental Status Evaluationmunir houseNo ratings yet

- Appearance and General BehaviorDocument3 pagesAppearance and General BehaviorHardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Question CHNDocument4 pagesQuestion CHNPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- TFN Review UNIT 7Document14 pagesTFN Review UNIT 7Pia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Agusan Del Norte Provincial Hospital: Memorandum No. 224Document2 pagesAgusan Del Norte Provincial Hospital: Memorandum No. 224Pia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Grand Par Psychia Manuscript FinalDocument85 pagesGrand Par Psychia Manuscript FinalPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Ojas Groupgrand Par Psychia Manuscript FinalDocument87 pagesOjas Groupgrand Par Psychia Manuscript FinalPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Subjective Cues: Short Term Goal: Short Term GoalDocument3 pagesSubjective Cues: Short Term Goal: Short Term GoalPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- BUAYAPIA ReflectionJournalDocument12 pagesBUAYAPIA ReflectionJournalPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Guide For History Taking AnamnesisDocument4 pagesGuide For History Taking AnamnesisPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Operating Room Scrub Form Major: Father Saturnino Urios UniversityDocument6 pagesOperating Room Scrub Form Major: Father Saturnino Urios UniversityPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Naso Gastric Tube Insertion and RemovalDocument5 pagesNaso Gastric Tube Insertion and RemovalPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Gibbs Buayan41Document2 pagesGibbs Buayan41Pia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Assessment I. General InformationDocument4 pagesNursing Assessment I. General InformationPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- 13 Contents of The Post Disaster Rehabilitation and Recovery Program of NDDRMC With Their MeaningsDocument3 pages13 Contents of The Post Disaster Rehabilitation and Recovery Program of NDDRMC With Their MeaningsPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Lucie Fink NCPsss - BUAYA PIA N32Document7 pagesLucie Fink NCPsss - BUAYA PIA N32Pia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Diagram For Data Gathering Procedure - BuayaDocument1 pageDiagram For Data Gathering Procedure - BuayaPia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Psychia Program Design GROUP2Document2 pagesPsychia Program Design GROUP2Pia Mae BuayaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Aqua-Aerobic On The Emotional States of WomenDocument4 pagesEffects of Aqua-Aerobic On The Emotional States of WomencristianxixonaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Work-Environment and Plant UtilityDocument2 pagesChapter 6 - Work-Environment and Plant UtilityRakib HasanNo ratings yet

- Reflective EssayDocument5 pagesReflective Essayapi-491857680No ratings yet

- The Five TemptationsDocument2 pagesThe Five TemptationsPawan Kumar100% (1)

- Tameca Dale Philosophy of NursingDocument4 pagesTameca Dale Philosophy of Nursingapi-359277730No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan-StabilityDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson Plan-StabilityechinodNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts in Item and Test AnaysisDocument11 pagesBasic Concepts in Item and Test AnaysisAkamonwa KalengaNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory Separation Anxiety and MourningDocument52 pagesAttachment Theory Separation Anxiety and Mourningkkarmen76100% (9)

- Carl Gustav Jung On DreamsDocument15 pagesCarl Gustav Jung On DreamsGaia Iulia AgrippaNo ratings yet

- Intolerance of Uncertainty and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Dimensions - KhakpoorDocument17 pagesIntolerance of Uncertainty and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Dimensions - KhakpoorSahelNo ratings yet

- Summative Test in ENGLISH 10: District of BoljoonDocument3 pagesSummative Test in ENGLISH 10: District of BoljoonZypher BlakeNo ratings yet

- Avery Purpose Statement Final 1Document9 pagesAvery Purpose Statement Final 1api-555568280No ratings yet

- MTA Cooperative GroupDocument10 pagesMTA Cooperative GroupmatiasNo ratings yet

- HOPE - PPT (Mass Communication)Document16 pagesHOPE - PPT (Mass Communication)Grisel GintingNo ratings yet

- Preschool ADHD QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesPreschool ADHD QuestionnaireAnnaNo ratings yet

- RCTNDocument51 pagesRCTNgiovanniquaNo ratings yet

- An Informa Business: 91956.casewrap - Indd 1Document22 pagesAn Informa Business: 91956.casewrap - Indd 1Raysa SilvaNo ratings yet

- Pembinaan Hubungan Guru Dan Murid Semasa PDPCDocument13 pagesPembinaan Hubungan Guru Dan Murid Semasa PDPCtia fateyhahNo ratings yet

- CB - Module 2Document17 pagesCB - Module 2Dr VIRUPAKSHA GOUD GNo ratings yet

- NHSLeadership LeadershipModel Colour PDFDocument16 pagesNHSLeadership LeadershipModel Colour PDFIsmaNo ratings yet

- Perdev Fidp Sy 2020-2021Document10 pagesPerdev Fidp Sy 2020-2021Tara Bautista100% (2)

- Research QuestionsDocument2 pagesResearch QuestionsFrances Gallano Guzman AplanNo ratings yet

- The Genius of Instinct (Extract)Document9 pagesThe Genius of Instinct (Extract)Padme11No ratings yet

- Psi Lesson 6 Mask Pre-Made Masks Drama Physical Education Rachel Nibogie 1Document5 pagesPsi Lesson 6 Mask Pre-Made Masks Drama Physical Education Rachel Nibogie 1api-710586400No ratings yet

- Skills For Successful MentoringDocument16 pagesSkills For Successful Mentoringtaap100% (1)

- Parental ModelDocument5 pagesParental ModelsorayalinNo ratings yet

- Instructional Materials: Human and Non-HumanDocument35 pagesInstructional Materials: Human and Non-HumanedisonNo ratings yet

- SN Yr 4 DLPDocument1 pageSN Yr 4 DLPAnonymous jHgxmwZNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Homework Nisa Risma Nindy PrimaDocument2 pagesAdvantages of Homework Nisa Risma Nindy PrimaTrijan RomadonaNo ratings yet

- Forensic Psychiatric Mental Evaluation - Mark Vance Halburn 07c-198Document9 pagesForensic Psychiatric Mental Evaluation - Mark Vance Halburn 07c-198Putnam Reporter100% (2)