Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Corporate Criminal Liability

Corporate Criminal Liability

Uploaded by

Yashraj Dokania0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views24 pagesOriginal Title

Corporate Criminal Liability (1)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views24 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability

Corporate Criminal Liability

Uploaded by

Yashraj DokaniaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 24

Corporate Criminal Liability

• A company can only act through human beings

and a human being who commits an offence

on account of or for the benefit of a company

will be responsible for that offence himself.

• The importance of incorporation is that it

makes the company itself liable in certain

circumstances, as well as the human beings.

---------Glanville Williams

Introduction

• In criminal law, corporate liability determines the extent to which

a corporation as a legal person can be liable for the acts and

omissions of the natural persons it employs.

• It is sometimes regarded as an aspect of criminal vicarious

liability, as distinct from the situation in which the wording of a

statutory offence specifically attaches liability to the company /

corporation.

• The basic rule of criminal liability revolves around the Latin

maxim actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea.

• It means that to make one liable it must be shown that act or

omission has been done which was forbidden by law and has

been done with guilty mind

Historical Evolution

• The general belief in the early sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was

that corporations could not be held criminally liable.

• Legal thinkers did not believe that corporations could possess the moral

blameworthiness necessary to commit crimes of intent.

• It was the common intent of the people that a corporation has no soul,

hence it cannot have "actual wicked intent”

• During the early twentieth century courts began to hold corporations

criminally liable in various areas in which enforcement would be

impeded without corporate liability

• Major hurdles that faced the attribution of criminal liability on

corporates were factors such as :--

1. artificial juristic personality and

2. absence of mens rea on the part of the corporate.

Corporate criminal liability in India

• All the Penal liabilities are generally regulated

under the IPC, 1860 in India.

• It is this statute which needs to be pondered

upon in case of criminal liability of corporation

Corporate Criminal Liability

Case Law -- Pre-Standard Chartered Bank

Indian courts held that corporations could not be prosecuted for offenses

requiring a mandatory punishment of imprisonment, as they could not be

imprisoned.

In A. K. Khosla v. S. Venkatesan (1992) Cr.L.J. 1448,

Two corporations were charged with having committed fraud under the IPC.

The Magistrate issued process against the corporations. The Court in this case

pointed out that there were two pre-requisites for the prosecution of corporate

bodies,

1. the first being that of mens rea and

2. the other being the ability to impose the mandatory sentence of imprisonment.

A corporate body could not be said to have the necessary mens rea , nor can

it be sentenced to imprisonment as it has no physical body.

In Kalpanath Rai v State (Through CBI) (1997) 8 SCC 732

• A company accused and arraigned under the Terrorists and Disruptive

Activities Prevention (TADA) Act, was alleged to have harbored terrorists.

trial court convicted the company - section 3(4) of the TADA Act- appeal S C

referred - definition "harbor" -Section 52A IPC- nothing to indicate- mens rea

excluded

• There is uncertainty over whether a company can be convicted for an

offence where the punishment prescribed by the statute is imprisonment

and fine.

• This controversy was first addressed in MV Javali v. Mahajan Borewell & Co

and Ors -S C-- held that mandatory sentence of imprisonment and fine is to

be imposed where it can be imposed, but where it cannot be

imposed ,namely on a company then fine will be the only punishment

In Zee Tele films Ltd. v. Sahara India Co. Corp. Ltd (2001) 3 Recent

Criminal Reports 292

• the court a complaint dismissed -Section 500 of the IPC-alleged that

Zee had telecasted a program based on falsehood and thereby defamed

Sahara India-held that mens rea was one of the essential elements of

the offense of criminal defamation and that a company could not have

the requisite mens rea.

In another case, Motorola Inc. v. Union of India (2004) Cri.L.J. 1576,

the Bombay H C quashed a proceeding- for alleged cheating, as it came

to the conclusion that it was impossible for a corporation to form the

requisite mens rea, which was the essential ingredient of the offense.

Thus, the corporation could not be prosecuted under section 420 of

the IPC.

In The Assistant Commissioner, Assessment-II, Bangalore & Ors. v. Velliappa

Textiles,

• a private company was prosecuted- Sections 276-C and 277 of the ITA provided

for a sentence of imprisonment –S C held -company could not be prosecuted

• - each sections required the imposition of a mandatory term of imprisonment

coupled with a fine.

• The sections in question left the court unable to impose only a fine. Indulging

in a strict and literal analysis, the Court held that a corporation did not have a

physical body to imprison and therefore could not be sentenced to

imprisonment.

• The Court also noted that when interpreting a penal statute , if more than one

view is possible, the court is obliged to lean in favour of the construction that

exempts an accused from penalty rather than the one that imposes the

penalty.

Standard Chartered Bank and Ors. v. Directorate of Enforcement (2005) 4

SCC 530

• Standard Chartered Bank was being prosecuted for violation of certain

provisions of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973

• Supreme Court held that the corporation could be prosecuted and punished,

with fines, regardless of the mandatory punishment required under the

respective statute.

In Velliappa Textiles case, the Bank could be prosecuted and punished for an

offense involving rupees one lakh or less as the court had an option to

impose a sentence of imprisonment or fine.

However, in the case of an offense involving an amount exceeding rupees

one lakh, where the court is not given discretion to impose imprisonment or

fine that is, imprisonment is mandatory, the Bank could not be prosecuted.

• view of different High Courts in India was very

inconsistent

in State of Maharashtra v. Syndicate (1963)

Transport Bom. L.R. 197

• High Court had held that the company could not be

prosecuted for offenses which necessarily entailed

corporal punishment or imprisonment; prosecuting a

company for such offenses would only result in a trial

with a verdict of guilty and no effective order by way

of a sentence.

in Oswal Vanaspati & Allied Industries v. State of Uttar Pradesh Comp.L.J.172

• The Full Bench of the Allahabad High Court had disagreed: “A company being a

juristic person cannot obviously be sentenced to imprisonment as it cannot

suffer imprisonment.

• It is settled law that sentence or punishment must follow conviction; and if

only corporal punishment is prescribed, a company which is a juristic person

cannot be prosecuted as it cannot be punished.

• If, however, both sentence of imprisonment and fine is prescribed for natural

persons and juristic persons jointly, then, though the sentence of

imprisonment cannot be awarded to a company, the sentence of fine can be

imposed on it.

• Legal sentence is the sentence prescribed by law.

A sentence which is in excess of the sentence prescribed is always illegal; but a

sentence which is less than the sentence may not in all cases be illegal”

• The Supreme Court in this particular case held:“We do not

think that the intention of the Legislature is to give

complete immunity from prosecution to the corporate

bodies for these grave offenses.

• The offenses mentioned under Section 56(1) of the FERA

Act, 1973 for which the minimum sentence of six months'

imprisonment is prescribed, are serious offenses and if

committed would have serious financial consequences

affecting the economy of the country.

• All those offenses could be committed by company or

corporate bodies.

We do not think that the legislative intent is not to

prosecute the companies for these serious offenses, if

these offenses involve the amount or value of more than

one lakh, and that they could be prosecuted only when the

offenses involve an amount or value less than one lakh.”

• By implication, it can be said that post Standard Chartered

decision, corporations are capable of possessing the

requisite mens rea.

• As in prosecution of other economic crimes, intention

could very well be imputed to a corporation and may be

gathered from the acts and/or omissions of a corporation

Corporate Criminal Liability

Post-Standard Chartered Bank Case

In Iridium India Telecom Ltd. v. Motorola Incorporated and Ors AIR

2011 SC 20,

• the apex court held that a corporation is virtually in the same

position as any individual and may be convicted under common

law as well as statutory offences including those requiring mens

rea.

In CBI v. M/s Blue-Sky Tie-up Ltd and Ors Crl. Appeal No(s). 950 of

2004,

• the apex court reiterated the position of law held that companies

are liable to be prosecuted for criminal offences and fines may be

imposed on the companies.

Can Criminal Liability of Corporation be

determined through Imprisonment?

• in case of corporation, Imprisonment cannot be recognised

even for serious offences mentioned under the IPC. Since, there

is no explicit provision relating to it, Hence the apex court in

various cases have held that it is better to impose fine

• The argument that a corporation has no soul to damn and no

body to imprison cuts both ways.

• Critics use it to argue that there is no reason to prosecute a

corporation.

• Supporters of corporate criminal liability might turn the

argument around and ask what’s the big deal, since the

corporation can’t go to jail?

• Corporate liability may appear incompatible with the

aim of deterrence because a corporation is a fictional

legal entity and thus cannot itself be “deterred.”

• In reality, the law aims to deter the unlawful acts or

omissions of a corporation’s agents.

• To defend corporate liability in deterrence terms,

one must show that it deters corporate managers or

employees better than does direct individual liability.

International Scenario

• The criminal sanctions are quite high and criminal liability of a

company is recognized by the Australian Legislation.

• Moreover, the Australian legislature have introduced criminal

liability of directors

• A basic principle of German law is societas delinquere non potest,

which means that a corporate body cannot be liable for a criminal

offence.

• But Germany has developed an elaborate structure of

administrative sanctions, which includes provisions on corporate

criminal liability. These so called Ordnungswidrigkeiten are handed

down by administrative bodies.

• It has provision for fine as punishment.

• Corporate criminal liability is an integral part of

Japanese law.

• There are currently more than 700 criminal provisions

on the national level alone, which can punish entities

other than individuals.

• China’s Criminal Code, which was first introduced in

1979, did not contain a provision on corporate

criminal liability until 1997.

Prior to the introduction of “unit crime” into the

Criminal Code in Article 30

• 8th International Conference of the Society for the Reform

of Criminal Law in 1994 in Hong Kong and the International

Meeting of Experts on the Use of Criminal Sanctions in the

Protection of the Environment in Portland, in 1994

• United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and

the Treatment of Offenders of 1985

• 1998, the Council of Europe passed the Convention on the

Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law, which

stipulated in Article 9 that both "criminal or administrative,

sanctions or measures” could be taken in order to hold

corporate entities accountable.

In India

• The wave of corruption scandals is affecting India very badly.

• In order to fix this it is relevant to examine criminal liability,

not just of individual directors or agents of a corporation, but

also of the company itself.

• Although considerable debate surrounds society’s increasing

reliance on criminal liability to regulate corporate conduct,

few have questioned in depth the fundamental basis for

imposing criminal liability on corporations.

• Accordingly Courts is based on the maxim lex non cogit ad

impossibilia, which tells us that law does not contemplate

something which cannot be done.

• But the statutes in India are not in pace with these

developments and the above analysis shows that

they do not make corporations criminally liable and

even if they do so, the statutes and judicial

interpretations impose no other punishments except

for fines.

• So it is inevitable to take some serious measures in

relation to the criminal liability of corporation so

that it could be stopped from the multiple

dimensions of the court’s decision.

• Absent the possibility of criminal liability, corporations

would escape moral conviction for wrongdoing, and the

retributive import of criminal liability to the community

would be lost.

• For under a civil liability regime for the corporation qua

corporation, there would be no moral condemnation

equivalent to a criminal conviction: if found civilly liable, a

corporation might be deemed negligent, or perhaps

reckless, but no statement, in the form of a conviction,

would attest to the proper valuation of the persons or

goods at issue.

• In the end, the financial liability imposed would come to be

viewed, by both the corporation and the community, merely as a

cost of doing business.

• In effect, then, a corporate civil liability regime that paralleled

ordinary criminal liability for individuals charged with the same

wrongdoing would allow the corporation qua corporation to

purchase exemption from moral condemnation.

• Such exemption would affect the expressive significance of

criminal liability, as the vindication of the proper valuations of

persons and goods would vary not with the conduct alleged--a

distinction that rightly could affect the evaluative standard

employed--but, rather, with the identity of the offender.

You might also like

- English Words From Latin and Greek Roots A Dictionary of Latin and Greek Roots in English Vocabulary (Abhinav Kushwaha)Document110 pagesEnglish Words From Latin and Greek Roots A Dictionary of Latin and Greek Roots in English Vocabulary (Abhinav Kushwaha)genie redNo ratings yet

- Nathan Roberts - The Doctrine of The Shape of The Earth - A Comprehensive Biblical Perspective (2017) PDFDocument64 pagesNathan Roberts - The Doctrine of The Shape of The Earth - A Comprehensive Biblical Perspective (2017) PDFyohannesababagaz100% (2)

- Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide: Scope for a New Legislation in IndiaFrom EverandCorporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide: Scope for a New Legislation in IndiaNo ratings yet

- Vicarious Corporate Criminal LiabilityDocument11 pagesVicarious Corporate Criminal LiabilityHenry100% (1)

- Shodh - : Market Research For Economy HousingDocument6 pagesShodh - : Market Research For Economy HousingAnand0% (1)

- Shodh - : Market Research For Economy HousingDocument6 pagesShodh - : Market Research For Economy HousingAnand0% (1)

- Catawba Indians Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesCatawba Indians Lesson Planapi-301878021No ratings yet

- A Rose For EmilyDocument8 pagesA Rose For EmilyLa neigeNo ratings yet

- Indian Penal CodeDocument115 pagesIndian Penal CodeShekhar SumanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Liability of Legal PersonDocument15 pagesCriminal Liability of Legal PersonAnusha RamanathanNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal Liability in IndiaDocument10 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability in IndiaHiteshi AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Dispute Resolution Hotline: OthersDocument6 pagesDispute Resolution Hotline: Otherssarayu alluNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal LiabilityDocument49 pagesCorporate Criminal LiabilityVishnu Pathak100% (1)

- PCRL 8Document3 pagesPCRL 8ANAND GEO 1850508No ratings yet

- Orporate Riminal Iability: Business Negligence, Liability and Law (BNLL-A)Document4 pagesOrporate Riminal Iability: Business Negligence, Liability and Law (BNLL-A)Yadhu Gopal GNo ratings yet

- Research Note - Corporate Criminal LiabilityDocument3 pagesResearch Note - Corporate Criminal Liabilityabbajpai666No ratings yet

- C.B.I. vs. Blue - Sky Tie-Up Limited & Ors.Document4 pagesC.B.I. vs. Blue - Sky Tie-Up Limited & Ors.sanjayankr100% (1)

- Standard Chartered Bank and Ors. Etc. VsDocument22 pagesStandard Chartered Bank and Ors. Etc. VsPrem ChopraNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal LiabilityDocument7 pagesCorporate Criminal LiabilityNiraj GuptaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 7Document7 pagesSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 7Abhishek YadavNo ratings yet

- The Companies Act, 2013: Session 2,3Document21 pagesThe Companies Act, 2013: Session 2,3Shravani SinghNo ratings yet

- "Piercing The Corporate Veil-Indian Scenario: Submitted byDocument11 pages"Piercing The Corporate Veil-Indian Scenario: Submitted byyash tyagiNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal Liability ProjectDocument10 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability ProjectAkash JainNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal LiabilityDocument16 pagesCorporate Criminal LiabilityAstitva SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Lifting of Corporate Veil of Company Under Company LawDocument5 pagesLifting of Corporate Veil of Company Under Company Lawyogesh_96No ratings yet

- Yashwant Rai Vyas-Criminal LiabiltyDocument6 pagesYashwant Rai Vyas-Criminal Liabiltymiss faiNo ratings yet

- CORPORATE LAW ProjectDocument14 pagesCORPORATE LAW Projectprathmesh agrawalNo ratings yet

- LEMCASEDocument15 pagesLEMCASEAkash DidhariaNo ratings yet

- GPCLDocument6 pagesGPCLGourav LohiaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal Liability ProjectDocument12 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability ProjectAshish Dahariya67% (3)

- DR - Navrang Saini-IBC CASE LAWSDocument10 pagesDR - Navrang Saini-IBC CASE LAWSSachinNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document9 pagesSession 1Gunjan ModiNo ratings yet

- Lifting of Corporate VeilDocument11 pagesLifting of Corporate VeilKhushwant NimbarkNo ratings yet

- Assignment On CompanyDocument8 pagesAssignment On CompanyHossainmoajjemNo ratings yet

- Opc and Corporate VeilDocument12 pagesOpc and Corporate Veilmugunthan100% (1)

- III. NATURE AND ATTRIBUTES OF A CORPORATION (5. Corporate Criminal Liability)Document2 pagesIII. NATURE AND ATTRIBUTES OF A CORPORATION (5. Corporate Criminal Liability)christine jimenezNo ratings yet

- Bell House Case AnalysisDocument7 pagesBell House Case AnalysisMunniBhavnaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Criminal Liability: A Critical Legal Study: Vijay Veer SinghDocument3 pagesCorporate Criminal Liability: A Critical Legal Study: Vijay Veer SinghKashish HarwaniNo ratings yet

- Company Law Answer Paper - 1Document3 pagesCompany Law Answer Paper - 1Nitesh MamgainNo ratings yet

- Notes On Companies Act 1956Document87 pagesNotes On Companies Act 1956Pranay KinraNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument17 pagesProjectllm075223No ratings yet

- Plea BargainingDocument6 pagesPlea BargainingAnya SinghNo ratings yet

- Summary of Arguments StarDocument2 pagesSummary of Arguments StarSuhani ChanchlaniNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu National Law University (A State University Established by Act No.9 of 2012) Navalurkuttapattu, Srirangam, Tiruchirappalli - 620 009Document12 pagesTamil Nadu National Law University (A State University Established by Act No.9 of 2012) Navalurkuttapattu, Srirangam, Tiruchirappalli - 620 009Mohamed RaaziqNo ratings yet

- Lifting of The Corporate Veil by Sivaganga.S.RDocument8 pagesLifting of The Corporate Veil by Sivaganga.S.RSiva Ganga SivaNo ratings yet

- Case Laws HhhhhhhhhhhhhhdalijDocument11 pagesCase Laws HhhhhhhhhhhhhhdalijarafatNo ratings yet

- Joel Odong Amen Anor V DrOcero Andrew Anor (HCT00CCCS 602 of 2004) 2006 UGCommC 51 (30 November 2006)Document11 pagesJoel Odong Amen Anor V DrOcero Andrew Anor (HCT00CCCS 602 of 2004) 2006 UGCommC 51 (30 November 2006)David OkelloNo ratings yet

- The Case For Corporate Criminal Liability: ArticleDocument47 pagesThe Case For Corporate Criminal Liability: ArticleIshita AgarwalNo ratings yet

- National Conference ON (6 April, 2019) : Corporate AffairsDocument12 pagesNational Conference ON (6 April, 2019) : Corporate Affairsaruba ansariNo ratings yet

- Shri Ambica Mills LTDDocument4 pagesShri Ambica Mills LTDBhuvneshwari RathoreNo ratings yet

- Plea Bargaining CRPCDocument7 pagesPlea Bargaining CRPCAnirudh VictorNo ratings yet

- Legal Liabilities of CompanyDocument8 pagesLegal Liabilities of CompanyPawan SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Company Law Lifting of Corporate Veil: Positive Approach: Adyasha Nanda Ba LLB (A) 3 Year, 5 Semester 1783007Document5 pagesCompany Law Lifting of Corporate Veil: Positive Approach: Adyasha Nanda Ba LLB (A) 3 Year, 5 Semester 1783007AdyashaNo ratings yet

- Case Laws - Part ADocument6 pagesCase Laws - Part Azf8dkk8fnzNo ratings yet

- Nestle Case StudyDocument8 pagesNestle Case StudyAkshaya ilangoNo ratings yet

- Moa/# - ftn3: Definition of Memorandum of AssociationDocument10 pagesMoa/# - ftn3: Definition of Memorandum of AssociationshivamNo ratings yet

- Companies Act 2013Document97 pagesCompanies Act 2013vchubytNo ratings yet

- Company Law: Model Answers June 2020Document31 pagesCompany Law: Model Answers June 2020stuti ghalayNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 2Document3 pagesTutorial 2猪mongNo ratings yet

- Whether An Arbitral Tribunal Can Uplift The Corporate Veil?Document3 pagesWhether An Arbitral Tribunal Can Uplift The Corporate Veil?Shejal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Model Answer Corporate MBL 69269Document17 pagesModel Answer Corporate MBL 69269Shrikant BudholiaNo ratings yet

- Lifting of Corporate VeilDocument6 pagesLifting of Corporate VeilSwastikaRaushniNo ratings yet

- 3.notes On Lifting of The Corporate VeilDocument4 pages3.notes On Lifting of The Corporate VeilramNo ratings yet

- Corporate Law 1 Research PaperDocument23 pagesCorporate Law 1 Research Paperyaswanth ramNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law Work 1Document9 pagesAdministrative Law Work 1bagumaNo ratings yet

- A Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsFrom EverandA Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Safal Niveshak Stock Analysis Excel (Ver. 3.0) : How To Use This SpreadsheetDocument32 pagesSafal Niveshak Stock Analysis Excel (Ver. 3.0) : How To Use This SpreadsheetAnandNo ratings yet

- Category Manager Role at UrbanClapDocument9 pagesCategory Manager Role at UrbanClapAnandNo ratings yet

- TT Post 09-11-18Document3 pagesTT Post 09-11-18AnandNo ratings yet

- Aerofarms: The Case For Collaborations in Education: Prepared For David Rosenberg and Stefan ObermanDocument22 pagesAerofarms: The Case For Collaborations in Education: Prepared For David Rosenberg and Stefan ObermanAnandNo ratings yet

- CBM Group AssignmentDocument1 pageCBM Group AssignmentAnandNo ratings yet

- Date Name Contact Alternate Contact Location 7/28/2019 Amresh Kumar 7654977073 8228043566 Muzaffarpur 7/28/2019 Nirmala Devi 8271982527 BhagalpurDocument2 pagesDate Name Contact Alternate Contact Location 7/28/2019 Amresh Kumar 7654977073 8228043566 Muzaffarpur 7/28/2019 Nirmala Devi 8271982527 BhagalpurAnandNo ratings yet

- Hoarding of Food GrainsDocument2 pagesHoarding of Food GrainsAnandNo ratings yet

- SDM - Case-Soren Chemicals - IB Anand (PGPJ02027)Document6 pagesSDM - Case-Soren Chemicals - IB Anand (PGPJ02027)AnandNo ratings yet

- 5th February 6th February: People Talking About Gerald CottenDocument2 pages5th February 6th February: People Talking About Gerald CottenAnandNo ratings yet

- Team and Organization-Wide Incentive Plans: Profit Sharing Plans: Scanlon PlanDocument1 pageTeam and Organization-Wide Incentive Plans: Profit Sharing Plans: Scanlon PlanAnandNo ratings yet

- CC1 (Extra Masala&Salt) CC2 (Shape of Nut) CC3 (Teekha Achari Masala)Document1 pageCC1 (Extra Masala&Salt) CC2 (Shape of Nut) CC3 (Teekha Achari Masala)AnandNo ratings yet

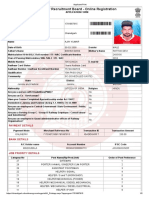

- Ajay Kumar - Applicant PrintDocument2 pagesAjay Kumar - Applicant PrintAnandNo ratings yet

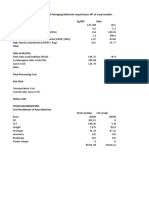

- Subject Marks Max. Marks Grade Grade Point 1. Manac 2. DWO 3. WEC 4. MM-II 5. ME-II 6. QAM-II 7. OM Total PercentageDocument4 pagesSubject Marks Max. Marks Grade Grade Point 1. Manac 2. DWO 3. WEC 4. MM-II 5. ME-II 6. QAM-II 7. OM Total PercentageAnandNo ratings yet

- Forecast Error: Suresh K Jakhar, PHD Indian Institute of Management LucknowDocument21 pagesForecast Error: Suresh K Jakhar, PHD Indian Institute of Management LucknowAnandNo ratings yet

- Subject Marks Max. Marks Grade Grade Point 1. Manac 2. DWO 3. WEC 4. MM-II 5. ME-II 6. QAM-II 7. OM Total PercentageDocument4 pagesSubject Marks Max. Marks Grade Grade Point 1. Manac 2. DWO 3. WEC 4. MM-II 5. ME-II 6. QAM-II 7. OM Total PercentageAnandNo ratings yet

- SL Particulars Currency of LoanDocument9 pagesSL Particulars Currency of LoanAnandNo ratings yet

- Breakfast Timings As Per Classes CommonDocument3 pagesBreakfast Timings As Per Classes CommonAnandNo ratings yet

- Air India - Fulfilment AIBE37491169 JMG3SDocument2 pagesAir India - Fulfilment AIBE37491169 JMG3SAnandNo ratings yet

- Sunita Singh ProfileDocument4 pagesSunita Singh ProfileAnandNo ratings yet

- International Markets Indices 2nd Jan 2018 12th Jan 2018 Gain/Loss (%)Document3 pagesInternational Markets Indices 2nd Jan 2018 12th Jan 2018 Gain/Loss (%)AnandNo ratings yet

- Group 7-Pay For Performance & Financial IncentivesDocument9 pagesGroup 7-Pay For Performance & Financial IncentivesAnandNo ratings yet

- Submitted By: Mahesh Raut IB Anand - Iim JammuDocument9 pagesSubmitted By: Mahesh Raut IB Anand - Iim JammuAnandNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Excel WorksheetDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Excel WorksheetAnandNo ratings yet

- MATPOST07 0043 PaperDocument6 pagesMATPOST07 0043 PaperNamLeNo ratings yet

- (SAGE Series On Men and Masculinity) Harry Brod, Michael Kaufman - Theorizing Masculinities-SAGE Publications, Inc (1994)Document314 pages(SAGE Series On Men and Masculinity) Harry Brod, Michael Kaufman - Theorizing Masculinities-SAGE Publications, Inc (1994)Daniel Arias OsorioNo ratings yet

- Sourabh Chandra - ResumeDocument4 pagesSourabh Chandra - ResumeNitin MahawarNo ratings yet

- Dina Iordanova - Women in Balkan Cinema, Surviving On The MarginsDocument17 pagesDina Iordanova - Women in Balkan Cinema, Surviving On The MarginsimparatulverdeNo ratings yet

- Official MPOW Complaint (4) (1) Uyre Majesty Akaxsha Ali El Bey Done XNX June 3 2021Document8 pagesOfficial MPOW Complaint (4) (1) Uyre Majesty Akaxsha Ali El Bey Done XNX June 3 2021ahmal coaxumNo ratings yet

- Radically Open DBT - Thomas LynchDocument601 pagesRadically Open DBT - Thomas LynchlizNo ratings yet

- HRD Final White Paper 31jul14Document23 pagesHRD Final White Paper 31jul14kongarajaykumarNo ratings yet

- Gaining Access, Developing Trust, Acting Ethically 7Document31 pagesGaining Access, Developing Trust, Acting Ethically 7Bisma NazirNo ratings yet

- Project ReportDocument112 pagesProject ReportfathimaNo ratings yet

- S 17 RBZDocument0 pagesS 17 RBZMike WrightNo ratings yet

- Soal Uas Bahasa Inggris Kelas 7 Semester 2Document4 pagesSoal Uas Bahasa Inggris Kelas 7 Semester 2Rinii Alfiiah100% (2)

- The Tavistock Learning Group - Exploration Outside The Traditional FrameDocument287 pagesThe Tavistock Learning Group - Exploration Outside The Traditional FrameNicolás BerasainNo ratings yet

- Paul Bragg Healthy HeartDocument260 pagesPaul Bragg Healthy Heartdeborah81100% (9)

- Order of Succession - Muslim Code of The PHDocument37 pagesOrder of Succession - Muslim Code of The PHPARANG DISTRICT JailNo ratings yet

- AcromegalyDocument3 pagesAcromegalylambomacNo ratings yet

- QuestionsDocument11 pagesQuestionsCicy IrnaNo ratings yet

- ProgramadeGestionHCR 2013-2019Document226 pagesProgramadeGestionHCR 2013-2019Yuri medranoNo ratings yet

- WhatsApp Use in A Higher Education Learning EnviroDocument15 pagesWhatsApp Use in A Higher Education Learning Envirotampala weyNo ratings yet

- Layers of SunDocument4 pagesLayers of SunSam JadhavNo ratings yet

- Inverse Polymerase Chain Reaction (Inverse PCR) Is A Variant of TheDocument8 pagesInverse Polymerase Chain Reaction (Inverse PCR) Is A Variant of TheNiraj Agarwal100% (1)

- DND Ebee 20061023aDocument8 pagesDND Ebee 20061023aSteampunkObrimosNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Jewish Studies: Instructions For AuthorsDocument13 pagesEuropean Journal of Jewish Studies: Instructions For AuthorschinguardNo ratings yet

- After Sales ServiceDocument4 pagesAfter Sales ServiceDan John KarikottuNo ratings yet

- Botulinum Toxin in CancerDocument11 pagesBotulinum Toxin in CancerAlicia Ramirez HernandezNo ratings yet

- OA3 - 6 B Sico - Unit 3Document3 pagesOA3 - 6 B Sico - Unit 3jhoel andradesNo ratings yet

- Brand Management ChickenSlice (PVT) LTDDocument31 pagesBrand Management ChickenSlice (PVT) LTDGabriel Chibanda100% (2)