Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fungal Pathogenesis - Helmi

Uploaded by

ERIE YUWITA SARIOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fungal Pathogenesis - Helmi

Uploaded by

ERIE YUWITA SARICopyright:

Available Formats

FUNGAL PATHOGENESIS

Dr. dr. Mardiastuti H Wahid, M.Sc., SpMK(K)

M Helmi A 1906 345 370

PROGRAM STUDI MIKROBIOLOGI KLINIK UI-RSCM

OUTLINE

1. Fungal infecting agent: Primary and Opportunistic pathogen.

2. Fungal virulence factors

3. Host factors – Susceptibility to fungal infection

4. Classes of infection based on site – 1: Subcutaneous and systemic fungal infection

1. Fungal Infecting Agent

INTRODUCTION

The virulence of fungi involves interaction of agent and host.

No single factor that causes or permits fungi to be agents of the diseases.

Fungal pathogens can be divided into two groups based on their virulence:

Primary pathogens Environmental reservoir, infect in large dose, or infect naïve people.

Opportunistic pathogen Fungi take advantage of immunocompromised state of the host;

Can be found in environment but also exist as commensals in the host.

Walsh TJ, 1996; Van Burik 2001

PRIMARY FUNGAL PATHOGEN

Several fungi are able to cause infection in immunocompetent hosts such as

Coccidioides immitis and Histoplasma capsulatum.

Infection by primary fungal pathogen Asymptomatic - Subclinical disease.

Occurs in people who live or travel in endemic areas (soil-related).

Walsh TJ, 1996; Van Burik 2001

PRIMARY FUNGAL PATHOGEN

R.G. Lewis, 2015

OPPORTUNISTIC FUNGAL PATHOGEN

Increasing due to medical practice survival of debilitated and immunosuppressed

patients.

Host factors play major role Local and systemic immune system impaired.

Virulence factors switching in absence of normal immune systems Opportunity

Unregulated growth Invasive infection.

Example of opportunistic fungi Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans.

Walsh TJ, 1996; Van Burik 2001

OPPORTUNISTIC FUNGAL PATHOGEN

Naglik JR, 2014

FUNGAL INFECTING AGENT

2. Fungal virulence factors

(Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016)

FUNGAL GROWTH

Ability to grow at body temperature and within fever range (37°C-42°C).

S. cerevisiae not a pathogenic fungi able to grow from pseudo-hyphae, infect-

persist in mice.

C. neoformans Calcineurin protein which required for growth 37°C. Disrupted

calcineurin avirulent strain of cryptococcal meningitis.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL GROWTH

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL ADHERENCE

Adherence Ability to resist from physical clearing.

HWP1 and INT1 gene Adherence of C. albicans in buccal epithelial cells and

filamentous growth of integrin-like-proteins When the gene is disrupted

Virulence of C. albicans was attenuated.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL ADHERENCE

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL PENETRATION AND DISSEMINATION

Infection of fungal may be limited to portal of entry or may become systemic.

In order to disseminate, fungal needs tissue damage which has already existed or the fungal

create the damage by mechanical penetration / tissue necrosis.

Candida has hyphae that can grow through the host cell walls.

A. fumigatus is able to penetrate blood vessel and grow in the lumen of blood vessel.

Fungal hyphae thigmotropically towards or away from touch stimulus.

Fungal also can spread by the host phagocytosis process (H. capsulatum, C. albicans).

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL PENETRATION AND DISSEMINATION

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL PENETRATION AND DISSEMINATION

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL PENETRATION AND DISSEMINATION

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL NUTRITION AND METABOLISM

Fungi able to carry biosynthetic reactions during the scarce of nutrients, synthetic

fatty acids, and glycolytic enzymes.

C. albicans auxotrophs (parent dependent) mutant experiment Diminish virulence.

H. capsulatum uracil auxotroph still virulent in cultured macrophage and mouse

model.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

FUNGAL NECROTIC FACTORS

Vehicles of virulence Overcome structural barrier to prevent invasive infection.

Most of the necrotic factors are enzymes, that usually used for nutritional enzymes

during saprophytic phase proteinase and phospolipases.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube,

MORPHOLOGY AND ADAPTATION -1

Almost all pathogenic fungi can grow in more than one form (except C. neoformans which only exist in the

yeast form in vivo).

Aspergillus Classical filamentous molds has conidia as the infectious agent.

Transition phase specific gene expression (i.e. in H. capuslatum) blocking acidification of phagosome.

Protect fungal from environmental changes aerobic to fermentative = switch to yeast to filamentous growth

of Candida.

Phenotypic switching white colonies (yeast cell-virulent) to opaque colonies (bean shaped cells-

colonization).

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

MORPHOLOGY AND ADAPTATION

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

MORPHOLOGY AND ADAPTATION - 2

Able to grow at different pH C. albicans can grow at acid and basic pH can colonize

vagina (acid) and oropharyngeal (neutral) regulated by PHR1 and PHR2 genes.

Produce toxin A. fumigatus produce toxin that can evade macrophage phagocytotis.

Surface properties C. neoformans produce polysaccharide capsule to prevent from

phagocytosus, downregulate cytokine secretion, prevent leukocyte accumulation, inhibit antigen

presentation, and inhibit lymphoproliferation Perfect host barrier defense.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

MORPHOLOGY AND ADAPTATION - 2

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

3. Host factors - Susceptibility to

fungal infection

IMMUNOCOMPETENCE

Estrogen-binding proteins Men are more likely than women to experience

disseminated infection (C. immitis) due to protective effect of 17β-estradiol (inhibiting

mycelial to yeast forms).

Underlying disease such as diabetes mellitus and pregnancy.

Diabetes Impair opsonisation and decreased chemotactic activity of immune cells.

Pregnancy Glycogen increase in vaginal tissue Vaginitis candida.

Burn wound vitims 10-fold-increase of fungal infections Topical antibacterial agents.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

IMMUNOCOMPETENCE

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

INFECTION ROUTES OF THE HOST

Endogenous C. albicans is part of the normal flora. Become pathogenic if it moves

from its site where us reacts to its presence. Breakdown of gut mucosa (chemotx,

radiation, trauma) allows commensal Candida to relocate from the gut to the

bloodstream.

Exogenous Fungi are carried in the air and inhaled.

Also can spread via hematogenous, direct inoculation, or ingestion.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

IMMUNOLOGY AND FUNGAL INFECTION

Humoral immunity Partial role in fungal infection.

Cell-mediated immunity Destroy fungal through phagocytosis or cytotoxicity.

Platelets against invasive aspergillosis.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

IMMUNOLOGY AND FUNGAL INFECTION

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

4. Classes of infection – Part 1

Subcutaneous and Systemic Fungal

Infection

SUBCUTANEOUS FUNGAL INFECTION

There are three general types of subcutaneous mycoses:

Chromoblastomycosis, Verrucoid lesions. Non-destructive.

Mycetoma Suppurative and granulomatous. Destructive.

Sporotrichosis. Spread along lymphatic channels.

Van Burik 2001; Brunke, Mogavero, Kasper, & Hube, 2016

SYSTEMIC FUNGAL INFECTION

Deep mycoses are caused by primary pathogenic and opportunistic fungal pathogens.

The primary pathogenic fungi are able to establish infection in a normal host

Respiratory spread.

Opportunistic pathogens require a compromised host in order to establish infection

Spread from respiratory tract, alimentary tract, or intravascular devices.

WHO SEARO, 2012; Arora D R 2004

REFERENCES

van Burik, J. A., & Magee, P. T. (2001). Aspects of fungal pathogenesis in humans. Annu Rev Microbiol, 55, 743-772. doi:

10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.743

Walsh TJ, Dixon DM. Spectrum of Mycoses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University

of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 75. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7902/

R. G. Lewis, Eric; R. Bowers, Jolene; M. Barker, Bridget (2015): Life cycle of Coccidioides.. PLOS Pathogens. Figure. https://

doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004762.g001

Naglik JR, Richardson JP, Moyes DL (2014) Candida albicans Pathogenicity and Epithelial Immunity. PLoS Pathog 10(8):

e1004257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004257

Brunke, S., Mogavero, S., Kasper, L., & Hube, B. (2016). Virulence factors in fungal pathogens of man. Current opinion in

microbiology, 32, 89-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2016.05.010

You might also like

- Part1 Medicinal Plants in PNGDocument172 pagesPart1 Medicinal Plants in PNGMadison Roland-Evans100% (6)

- Cosmology: Beyond The Big BangDocument60 pagesCosmology: Beyond The Big BangHaris_IsaNo ratings yet

- Review of Quality and Reliability HandbookDocument282 pagesReview of Quality and Reliability HandbookMohamed AbdelAzizNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionDocument15 pagesPathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionMichaelJJordan100% (1)

- A Molecular Perspective of Microbial Pathogenicity PDFDocument11 pagesA Molecular Perspective of Microbial Pathogenicity PDFjon diazNo ratings yet

- Bicon Surgical ManualDocument24 pagesBicon Surgical ManualBicon Implant InaNo ratings yet

- MYCOLOGYDocument33 pagesMYCOLOGYiwennieNo ratings yet

- Tad2 - Functional Concepts and The Interior EnvironmentDocument10 pagesTad2 - Functional Concepts and The Interior EnvironmentJay Reyes50% (2)

- Fabrication of 2 X 1000 MT Capacity Mounded LPG Storage VesselsDocument84 pagesFabrication of 2 X 1000 MT Capacity Mounded LPG Storage VesselsMilan DjumicNo ratings yet

- Clinical History and Examination of Patients With Infectious DiseaseDocument43 pagesClinical History and Examination of Patients With Infectious DiseaseMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.No ratings yet

- FCH, Communicable Diseases Syllabus (2020)Document277 pagesFCH, Communicable Diseases Syllabus (2020)jean uwakijijweNo ratings yet

- Infection Control and Safety MeasuresDocument29 pagesInfection Control and Safety MeasuresAlma Susan100% (1)

- Candida Glabrata, Candida Parapsilosis Andcandida Tropicalis PDFDocument18 pagesCandida Glabrata, Candida Parapsilosis Andcandida Tropicalis PDFNovena DpNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Fungal InfectionsDocument70 pagesPathogenesis of Fungal Infectionsማላያላም ማላያላም100% (15)

- Blrincon - Blrincon - 2023 Nature ReviewsDocument20 pagesBlrincon - Blrincon - 2023 Nature ReviewsDavidf VillabonaNo ratings yet

- Glowing Infections: Exposing Fungal Infections With BioluminescenceDocument4 pagesGlowing Infections: Exposing Fungal Infections With BioluminescenceRaffy LopezNo ratings yet

- Compilation of Infectious Diseases: A Project in Community and Public HealthDocument8 pagesCompilation of Infectious Diseases: A Project in Community and Public HealthAbigail VirataNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis To Viruses DDocument16 pagesPathogenesis To Viruses DJaydee PlataNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 FinalDocument52 pagesUnit 3 Finalsuhani.gnupadhyayNo ratings yet

- Virulence Factors & Pathogenesis of Fungal InfectionsDocument28 pagesVirulence Factors & Pathogenesis of Fungal InfectionsNipun ShamikaNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Immunity To Fungal InfectionsDocument13 pagesReviews: Immunity To Fungal InfectionsmonitamiftahNo ratings yet

- Mycoviruses and Their Role in Biological Control PDFDocument8 pagesMycoviruses and Their Role in Biological Control PDFvijayNo ratings yet

- Assignment On MycobacteriaDocument7 pagesAssignment On MycobacteriaAlamgir HossainNo ratings yet

- Mikrobiologi Parasitologi Respiration: AN IMO 2019Document64 pagesMikrobiologi Parasitologi Respiration: AN IMO 2019Sleeping BeautyNo ratings yet

- Tsui 2016Document51 pagesTsui 2016Arika EffiyanaNo ratings yet

- Aspergillus and Vaginal Colonization-2329-8731.1000e115Document2 pagesAspergillus and Vaginal Colonization-2329-8731.1000e115Hervis Francisco FantiniNo ratings yet

- Refrat Invasive Fungal InfectionsDocument26 pagesRefrat Invasive Fungal InfectionsRizkiantoNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Topic 1 Pathogenesis and Transmission of Bacterial Infection Copy 06102022 031705pmDocument21 pagesWeek 2 Topic 1 Pathogenesis and Transmission of Bacterial Infection Copy 06102022 031705pmTayyaba TahiraNo ratings yet

- What Is DiabetesDocument8 pagesWhat Is DiabetesJessica GintingNo ratings yet

- The Pulmonary Mycoses: Aaron Samuel Miller, MD, MSPH, and Robert William Wilmott, BSC, MB, BS, MD, FRCP (Uk)Document25 pagesThe Pulmonary Mycoses: Aaron Samuel Miller, MD, MSPH, and Robert William Wilmott, BSC, MB, BS, MD, FRCP (Uk)Klinikdr RIDHANo ratings yet

- The Pulmonary Mycoses: Aaron Samuel Miller, MD, MSPH, and Robert William Wilmott, BSC, MB, BS, MD, FRCP (Uk)Document25 pagesThe Pulmonary Mycoses: Aaron Samuel Miller, MD, MSPH, and Robert William Wilmott, BSC, MB, BS, MD, FRCP (Uk)Sarah Fitriani MuzwarNo ratings yet

- Fungal Infections in Diabetes Mellitus: An Overview: Review ArticleDocument5 pagesFungal Infections in Diabetes Mellitus: An Overview: Review ArticleAudrey Ira YunitaNo ratings yet

- TUBERCULOSISDocument13 pagesTUBERCULOSISSam VattaraiNo ratings yet

- 2 Gram Negative Bacterial InfectionDocument89 pages2 Gram Negative Bacterial InfectionCoy NuñezNo ratings yet

- Prof LoekiDocument45 pagesProf Loekiiryasti2yudistiaNo ratings yet

- Inmunidad de Las Infecciones FungicasDocument14 pagesInmunidad de Las Infecciones FungicasGabriel Gonzalez BinottoNo ratings yet

- HNS 2202 Lesson 2Document26 pagesHNS 2202 Lesson 2hangoverNo ratings yet

- Chap TwoDocument12 pagesChap Twovalerybikobo588No ratings yet

- Bello, Mabekoje and EfuntoyeDocument22 pagesBello, Mabekoje and EfuntoyeDR OLADELE MABEKOJENo ratings yet

- Minireview: Haemophilus Influenzae Infections in The H. Influenzae Type BDocument5 pagesMinireview: Haemophilus Influenzae Infections in The H. Influenzae Type BAna-Mihaela BalanuțaNo ratings yet

- MPH 5203 Communicable DiseasesDocument134 pagesMPH 5203 Communicable DiseasesOLIVIERNo ratings yet

- Chapter 56Document57 pagesChapter 56Rahmat MuliaNo ratings yet

- Paralytic Poliomyelitis Caused by A Vaccine-Derived Polio Virus in An Antibody-Deficient Argentinean ChildDocument3 pagesParalytic Poliomyelitis Caused by A Vaccine-Derived Polio Virus in An Antibody-Deficient Argentinean Childxiongmao2389No ratings yet

- Correspondence: Broad-And Narrow-Spectrum Antibiotics: A Different ApproachDocument2 pagesCorrespondence: Broad-And Narrow-Spectrum Antibiotics: A Different ApproachJulio Andro ArtamulandikaNo ratings yet

- Candida Albicans Biofilm: Formation And: Antifungal Agents ResistanceDocument9 pagesCandida Albicans Biofilm: Formation And: Antifungal Agents ResistanceaaaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionDocument35 pagesPathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionBenard NyaumaNo ratings yet

- Microbiology and ParasitologyDocument4 pagesMicrobiology and Parasitologyhannahusman61No ratings yet

- Ajidm 1 4 2Document6 pagesAjidm 1 4 2rehanaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Communicable DiseaseDocument32 pagesEpidemiology of Communicable DiseaseBalqees MohammedNo ratings yet

- Control of Communicable DiseaseDocument4 pagesControl of Communicable DiseaseBianca CordovaNo ratings yet

- AnthraxDocument11 pagesAnthraxrobbyrbbyNo ratings yet

- Candidiasis 3Document23 pagesCandidiasis 3ELSA NOVANTINo ratings yet

- CandidaDocument33 pagesCandidaAlberto ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 7761Document50 pagesUnit 6 7761Muhammad Abu Bakar Siddique 962-FET/BSME/F20No ratings yet

- MicrobioDocument34 pagesMicrobiodead yrroehNo ratings yet

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Ecology and Evolution of A Human BacteriumDocument9 pagesMycobacterium Tuberculosis: Ecology and Evolution of A Human Bacteriumsudipta KhilarNo ratings yet

- Immunology: MicrobiologyDocument7 pagesImmunology: MicrobiologyRemus MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Saint Mary's University School of Health and Natural Science Medical Laboratory Science DepartmentDocument5 pagesSaint Mary's University School of Health and Natural Science Medical Laboratory Science DepartmentAubrey NideaNo ratings yet

- BacteriologyDocument62 pagesBacteriologyJeul AzueloNo ratings yet

- Gonorrhea - An Evolving Disease of The New Millennium: ReviewDocument19 pagesGonorrhea - An Evolving Disease of The New Millennium: ReviewValeria Moretto VegaNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Resistance in Hospital-Acquired Gram-Negative Bacterial InfectionsDocument9 pagesAntimicrobial Resistance in Hospital-Acquired Gram-Negative Bacterial InfectionsAlina BanciuNo ratings yet

- GetahunLTBINEJM2015 PDFDocument9 pagesGetahunLTBINEJM2015 PDFSharah Stephanie IINo ratings yet

- EBS ProjectDocument9 pagesEBS Projectdiksha halderNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Medical MicrobiologyDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Medical MicrobiologyIsba Shadai Estrada GarciaNo ratings yet

- PIIS1201971216311134Document8 pagesPIIS1201971216311134Prasanta BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Viral Vistas: Insights into Infectious Diseases: The Invisible War: Decoding the Game of Hide and Seek with PathogensFrom EverandViral Vistas: Insights into Infectious Diseases: The Invisible War: Decoding the Game of Hide and Seek with PathogensNo ratings yet

- Kul Biomol Bakteri Ekspresi GenDocument28 pagesKul Biomol Bakteri Ekspresi GenERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Resistance Testing - AnaerobDocument21 pagesAntibiotic Resistance Testing - AnaerobERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- DNA and ChromosomeDocument35 pagesDNA and ChromosomeERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0013935115301766 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S0013935115301766 MainERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- ZJM 401Document11 pagesZJM 401ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- JCM 40 10 3814-3817 2002Document4 pagesJCM 40 10 3814-3817 2002ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Development of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0Document11 pagesDevelopment of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- 21-1145-Delayed T Cell and Ig Response After BT Pfizer Covid Vaccine in Eldery Juli21Document12 pages21-1145-Delayed T Cell and Ig Response After BT Pfizer Covid Vaccine in Eldery Juli21ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Microbiology-2019-Sathiananthamoorthy-e01452-18.fullDocument18 pagesJournal of Clinical Microbiology-2019-Sathiananthamoorthy-e01452-18.fullERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- ArchitechDocument5 pagesArchitechERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- 21-0965-Persisten of IgG in Children After CovidDocument7 pages21-0965-Persisten of IgG in Children After CovidERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- TeikyoDocument6 pagesTeikyoERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Diet Modified in ConsistencyDocument34 pagesDiet Modified in Consistencycriselda desistoNo ratings yet

- Job 38Document18 pagesJob 38Andrei GhidionNo ratings yet

- Adani Enterprises Limited: Financial Statement AnalysisDocument44 pagesAdani Enterprises Limited: Financial Statement AnalysisAyush FuseNo ratings yet

- Rohini 24928786475Document12 pagesRohini 24928786475aswinvirat84No ratings yet

- Flexi Multiradio 10 Base Station Transmission DescriptionDocument27 pagesFlexi Multiradio 10 Base Station Transmission DescriptionMohamedNasser Gad El MawlaNo ratings yet

- Transistor - Transistor Logic (TTL) : I LowDocument17 pagesTransistor - Transistor Logic (TTL) : I LowwisamNo ratings yet

- 7 140706224638 Phpapp01Document165 pages7 140706224638 Phpapp01Theodøros D' Spectrøøm0% (1)

- IEE EIA Introduction and ProcessDocument27 pagesIEE EIA Introduction and ProcessHari PyakurelNo ratings yet

- Industry X.0: Realizing Digital Value in Industrial SectorsDocument15 pagesIndustry X.0: Realizing Digital Value in Industrial SectorsJamey DAVIDSONNo ratings yet

- Smart Manufacturing For The Oil Refining and Petrochemical IndustryDocument4 pagesSmart Manufacturing For The Oil Refining and Petrochemical IndustryMd Sultan AhemadNo ratings yet

- Filariasis: Dr. Saida SharminDocument35 pagesFilariasis: Dr. Saida SharminBishwajit BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- Safety and Efficacy of Meloxicam in The TreatmentDocument9 pagesSafety and Efficacy of Meloxicam in The TreatmentIndra Hakim FadilNo ratings yet

- High-Precision Chilled Mirror HygrometerDocument4 pagesHigh-Precision Chilled Mirror HygrometerAldrin HernandezNo ratings yet

- Stories of Love and AdventureDocument24 pagesStories of Love and AdventureMargie HernandezNo ratings yet

- Automated Sand Gravity Sand Filter SystemDocument58 pagesAutomated Sand Gravity Sand Filter SystemMichaelNo ratings yet

- Caritas vs. Avarice: The Embroiled Church and Empire: John Michael PotvinDocument16 pagesCaritas vs. Avarice: The Embroiled Church and Empire: John Michael PotvinJohn PotvinNo ratings yet

- Teksas Tone Control MonoDocument17 pagesTeksas Tone Control MonoRhenz TalhaNo ratings yet

- Conference Tool Setup - RuckusDocument11 pagesConference Tool Setup - RuckusJohn MontuyaNo ratings yet

- Ijesrt: International Journal of Engineering Sciences & Research TechnologyDocument11 pagesIjesrt: International Journal of Engineering Sciences & Research TechnologyAna MariaNo ratings yet

- F.2 I.S. Vocabulary List (Unit 7-11)Document14 pagesF.2 I.S. Vocabulary List (Unit 7-11)2E (9) HON MARITA JANENo ratings yet

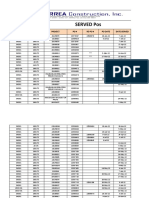

- Served POsDocument21 pagesServed POsYay DumaliNo ratings yet

- Mimaki CJV-150 PDFDocument146 pagesMimaki CJV-150 PDFKisgyörgy ZoltánNo ratings yet

- Vatusa-Vatnz-Vatpac: Oceanic PartnershipDocument10 pagesVatusa-Vatnz-Vatpac: Oceanic PartnershipJerome Cardenas TablacNo ratings yet

- Tetrasteel 800 BrochureDocument4 pagesTetrasteel 800 BrochurejcrandleNo ratings yet