Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GE Hca15 PPT ch13

Uploaded by

Intan Nadilah0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views35 pagesOriginal Title

GE_hca15_ppt_ch13

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views35 pagesGE Hca15 PPT ch13

Uploaded by

Intan NadilahCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 35

Pricing Decisions

and

Cost Management

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

1. Discuss the three major factors that affect

pricing decisions

2. Understand how companies make long-run

pricing decisions

3. Price products using the target-costing

approach

4. Apply the concepts of cost incurrence and

locked-in costs

5. Price products using the cost-plus approach

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-2

6. Use life-cycle budgeting and costing when

making pricing decisions

7. Describe two pricing practices in which

noncost factors are important

8. Explain the effects of antitrust laws on

pricing

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-3

How companies price a product or service

ultimately depends on the demand and

supply for it.

Three influences on demand and supply are:

1. Customers

2. Competitors

3. Costs

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-4

1. Customers—influence price through their

effect on the demand for a product or

service, based on factors such as product

features and quality.

2. Competitors—influence price through

their technologies, plant capacities and

operating strategies which affect their

costs.

3. Costs—influence prices because they

affect supply (the lower the cost, the

greater the quantity a firm is willing to

supply).

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-5

Short-run pricing decisions have a time

horizon of less than one year and include

decisions such as:

Pricinga one-time-only special order with no long-

run implications

Adjusting product mix and output volume in a

competitive market.

Long-run pricing is a strategic decision

designed to build long-run relationships

with customers based on stable and

predictable prices. Managers prefer a

stable price.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-6

Recall that indirect costs of a particular cost

object are costs that are related to that cost

object but cannot be traced to it in an

economically feasible (cost-effective) way.

These costs often comprise a large

percentage of the overall costs assigned to

cost objects.

Cost allocations influence managers’ cost

management decisions as well as the

products that managers promote.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-7

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-8

How should managers use product cost information to

price their products? There are two different

approaches for pricing decisions:

The MARKET-BASED APPROACH asks: Given what our

customers want and how competitors will react to what

we do, what price should we charge?

The COST-BASED APPROACH asks: Given what it costs

us to make this product, what price should we charge

that will recoup our costs and achieve a target return

on investment?

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-9

Companies operate in different markets which

affect the approach they’ll use for pricing:

Companies operating in COMPETITIVE MARKETS

use the market-based approach. Companies in

these markets must accept the prices set by the

market (goods or services provided by competitors

are very similar)

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-10

Companies operate in different markets which affect

the approach they’ll use for pricing:

Companies operating in LESS-COMPETITIVE MARKETS

offer products or services that differ from each other

and can use either the market-based or cost-based

approach as the starting point for pricing decisions.

Remember, both approaches consider customers,

competitors and costs. Only the starting points differ.

Managers should always keep in mind market forces

regardless of which pricing approach they use.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-11

Companies operate in different markets which

affect the approach they’ll use for pricing:

Companies operating in markets that are NOT

COMPETITIVE favor cost-based approaches because

these companies do not need to respond or react

to competitors’ prices.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-12

Before setting prices under any approach, managers

need to understand customers and competitors for

three reasons:

1. Lower-cost competitors continually restrain prices.

2. Products have shorter lives, which leaves

companies less time and opportunity to recover

from pricing mistakes, loss of market share and

loss of profitability.

3. Customers are more knowledgeable because they

have easy access to price and other information

online and demand high-quality products at low

prices.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-13

Starts with a target price which is the estimated

price for a product or service that potential

customers are willing to pay

The target price is estimated based on

1. an understanding of customers’ perceived value

for a product or service, and

2. How competitors will price competing products or

services.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-14

1. Develop a product that satisfies the needs of

potential customers.

2. Choose a target price.

3. Derive a target cost per unit by subtracting target

operating income per unit from the target price

4. Perform cost analysis.

5. Perform value engineering to achieve target cost.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-15

Value engineering is a systematic evaluation of all

aspects of the value chain, with the objective of

reducing costs and achieving a quality level that

satisfies customers.

Value engineering entails improvements in product

designs, changes in materials specifications and

modifications in process methods.

To implement value engineering, managers must

distinguish value-added activities and costs from

non-value-added activities and costs.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-16

Value-added costs—a cost that, if eliminated,

would reduce the actual or perceived value or

utility (usefulness) customers experience from

using the product or service.

Non-value-added costs—a cost that, if

eliminated, would not reduce the actual or

perceived value or utility (usefulness)

customers gain from using the product or

service. It is a cost the customer is unwilling to

pay for. (Examples include the cost of

defective products and machine breakdowns.)

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-17

Cost incurrence—describes when a resource is

consumed (or benefit foregone) to meet a

specific objective.

Locked-in costs (designed-in costs)—are costs

that have not yet been incurred but will be

incurred in the future based on decisions that

have already been made.

The best opportunity to manage costs is before

they are locked in.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-18

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-19

Unless managed properly, value engineering and target

costing can have undesirable effects:

1.Employees may feel frustrated if they fail to attain

targets.

2.The cross-functional team may add too many features

just to accommodate the different wishes of team

members.

3.A product may be in development for a long time as

the team repeatedly evaluates alternative designs.

4.Organizational conflicts may develop as the burden of

cutting costs falls unequally on different business

functions in the company’s value chain.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-20

To avoid those possible undesirable effects,

target-costing efforts should always:

1.Encourage employee participation and

celebrate small improvements toward

achieving the target cost.

2.Focus on the customer.

3.Pay attention to schedules.

4.Set cost-cutting targets for all value-chain

functions to encourage a culture of teamwork

and cooperation.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-21

The target pricing approach is another illustration

of the five-step decision-making process

introduced in Chapter 1:

1.Identify the problem and uncertainties.

2.Obtain information.

3.Make predictions about the future.

4.Make decisions by choosing among alternatives

5.Implement the decision, evaluate performance

and learn.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-22

Instead of using the market-based approach for long-

run pricing decisions, managers sometimes use a cost-

based approach

The general formula for setting a cost-based selling

price adds a markup component to the cost base.

Usually, it is only a starting point in the price-setting

process.

Markup is somewhat flexible, based partially on

customers and competitors.

Because a markup is added, cost-based pricing is often

called cost-plus pricing, where the plus refers to the

markup component.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-23

Cost-plus pricing can be determined several ways:

Choose a markup to earn a target rate of return

on investment, which is the target annual

operating income divided by invested capital

Computing the specific amount of capital

invested in a product is challenging because it

requires difficult and arbitrary allocations of

investments in equipment and buildings to

individual products.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-24

Because computing the specific amount of

capital invested in a product is challenging,

sometimes managers use alternate cost bases

to set prospective selling prices:

Variable manufacturing cost

Variable cost

Manufacturing cost

Full cost

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-25

Most firms use full cost for their cost-based

pricing decisions, because:

It allows for full recovery of all costs of the product.

It allows for price stability.

It is a simple approach.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-26

The selling prices computed under Cost-plus

pricing are prospective prices.

The Target-pricing approach reduces the

need to go back and forth among prospective

cost-plus prices, customer reactions and

design modifications.

Target-pricing first determines product

characteristics and target price on the basis

of customer preferences and expected

competitor responses and then computes a

target cost.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-27

Managers sometimes need to consider target prices and

target costs over a multiple-year product life cycle.

Product life-cycle spans the time from initial R&D on a

product to when customer service and support are no

longer offered on that product (orphaned).

In Life-cycle budgeting, managers estimate the revenues

and business function costs across the entire value-chain

from its initial R&D to its final customer service and

support.

Life-cycle costing tracks and accumulates business function

costs across the entire value chain from a product’s initial

R&D to its final customer service and support.

Life-cycle budgeting and life-cycle costing span several

years.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-28

Budgeted life-cycle costs provide useful information

for strategically evaluating pricing decisions. These

two features of costs make life-cycle budgeting

particularly important.

The development period for R&D and design is long

and costly.

Many costs are locked in at the R&D and design

stages, even if R&D and design costs are themselves

small.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-29

Price discrimination—the practice of charging

different customers different prices for the same

product or service.

Legal implications

Peak-load pricing—the practice of charging a

higher price for the same product or service

when demand approaches the physical limit of

the capacity to produce that product or service

International pricing-prices charged in different

countries vary much more than the costs of

delivering the product to each country.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-30

Price discrimination is illegal if the intent is to

lessen or prevent competition.

Predatory pricing occurs when a company

deliberately prices below its costs in an effort to

drive competitors out of the market and restrict

supply, then raise prices rather than enlarge

demand.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-31

Dumping—occurs when a non-U.S. company sells a

product in the United States at a price below the

market value in the country where it is produced,

and this lower price materially injures or

threatens to materially injure an industry in the

United States.

Collusive pricing—occurs when companies in an

industry conspire in their pricing and production

decisions to achieve a price above the

competitive price and so restrain trade.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-32

TERMS TO LEARN PAGE NUMBER REFERENCE

Collusive pricing Page 536

Cost incurrence Page 525

Customer life-cycle costs Page 533

Designed-in costs Page 525

Dumping Page 536

Life-cycle budgeting Page 531

Life-cycle costing Page 531

Locked-in costs Page 525

Non-value-added costs Page 525

Peak-load pricing Page 534

Predatory pricing Page 535

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-33

TERMS TO LEARN PAGE NUMBER REFERENCE

Price discrimination Page 534

Product life cycle Page 531

Target cost per unit Page 523

Target operating income per unit Page 523

Target price Page 522

Target rate of return on Page 529

investment

Value-added cost Page 525

Value engineering Page 525

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-34

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education

13-35

You might also like

- Michael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageFrom EverandMichael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Pricing Decisions and Cost ManagementDocument29 pagesPricing Decisions and Cost Managementmzhao8No ratings yet

- GE PPT Ch13 Lecture 2 Pricing Decisions & Cost ControlDocument53 pagesGE PPT Ch13 Lecture 2 Pricing Decisions & Cost ControlZoe Chan100% (1)

- PRICING DECISIONS AND COST MANAGEMENTDocument3 pagesPRICING DECISIONS AND COST MANAGEMENTVagabondXikoNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting Strategy Study Resource for CIMA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesFrom EverandManagement Accounting Strategy Study Resource for CIMA Students: CIMA Study ResourcesNo ratings yet

- CMA CH 4 - Cost Analysis and Pricing Decisons March 2019-1Document30 pagesCMA CH 4 - Cost Analysis and Pricing Decisons March 2019-1Henok FikaduNo ratings yet

- Chap 13Document18 pagesChap 13Ashak Anowar MahiNo ratings yet

- Major Influences On Pricing DecisionsDocument4 pagesMajor Influences On Pricing DecisionsAbdullah Al RaziNo ratings yet

- Cost II CH 6 Pricing DecisionDocument17 pagesCost II CH 6 Pricing DecisionAshuNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Pricing DecisionDocument30 pagesLecture 6 - Pricing DecisionRaeka AriyandiNo ratings yet

- Customer Value in Business Markets: BenefitsDocument13 pagesCustomer Value in Business Markets: BenefitsRitesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Week 4 - Lecture - Pricing Decisions and Profitability AnalysisDocument16 pagesWeek 4 - Lecture - Pricing Decisions and Profitability Analysischina xiNo ratings yet

- AttachmentDocument35 pagesAttachmentMelkamu WoldeNo ratings yet

- Chap 015Document40 pagesChap 015palak32100% (2)

- SMChap 015Document40 pagesSMChap 015zoomblue200100% (2)

- Pricing Decisions and Cost ManagementDocument22 pagesPricing Decisions and Cost ManagementDr. Alla Talal YassinNo ratings yet

- Target Costing and Pricing Decisions AnalysisDocument50 pagesTarget Costing and Pricing Decisions AnalysisBea BlancoNo ratings yet

- Pricing - Understanding Customer ValueDocument31 pagesPricing - Understanding Customer ValueKelvin Namaona NgondoNo ratings yet

- Cost Analysis TechniquesDocument3 pagesCost Analysis Techniquesammi890No ratings yet

- EMNUTC01 - Group 3 Vietnamese Tea Agricultural Product - Report SummaryDocument7 pagesEMNUTC01 - Group 3 Vietnamese Tea Agricultural Product - Report SummaryThảo NguyễnNo ratings yet

- SM Module 4 Rev AnsDocument4 pagesSM Module 4 Rev AnsLysss EpssssNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five Pricing Strategy ExplainedDocument42 pagesChapter Five Pricing Strategy ExplainedAmanuel AbebawNo ratings yet

- MKT6 Course Explores Strategic Pricing and Value CreationDocument15 pagesMKT6 Course Explores Strategic Pricing and Value CreationPaula Marie De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- New State of The ArtDocument12 pagesNew State of The ArtDarrell SaricNo ratings yet

- Differentiate Strategy Key DriversDocument12 pagesDifferentiate Strategy Key DriversFrancisPKitara100% (1)

- MP 9Document9 pagesMP 9Pei Xin YauNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Fundamentals of Cost Accounting Lanen Anderson Maher 4th EditionDocument9 pagesSolution Manual For Fundamentals of Cost Accounting Lanen Anderson Maher 4th EditionDiane Jones100% (33)

- Cost & Pricing StrategiesDocument5 pagesCost & Pricing StrategiesMoti BekeleNo ratings yet

- Target Costing and Cost Analysis For Pricing Decisions: Answers To Review QuestionsDocument48 pagesTarget Costing and Cost Analysis For Pricing Decisions: Answers To Review QuestionsMJ Yacon0% (1)

- Target Costing and Pricing DecisionsDocument49 pagesTarget Costing and Pricing DecisionsJay Lord FlorescaNo ratings yet

- Target CostingDocument32 pagesTarget Costingapi-3701467100% (3)

- Manager and Accounting For ManagerDocument35 pagesManager and Accounting For ManagerrhagitaanggyNo ratings yet

- Project PricingDocument49 pagesProject Pricingseema talrejaNo ratings yet

- Purchasing Final Exam Reviewer 1Document4 pagesPurchasing Final Exam Reviewer 1carla duarteNo ratings yet

- Bpsa Unit 5Document13 pagesBpsa Unit 5nandiniNo ratings yet

- 7ps of MarketingDocument58 pages7ps of MarketingRaquel Sibal RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Cost Analysis For Decision Making: Solutions To Review QuestionsDocument62 pagesFundamentals of Cost Analysis For Decision Making: Solutions To Review QuestionsZYna ChaRisse TabaranzaNo ratings yet

- PriceDocument37 pagesPriceSahana S MendonNo ratings yet

- Chapter Ten: ILP108 Topic 9aDocument52 pagesChapter Ten: ILP108 Topic 9aKrisKettyNo ratings yet

- Pricing A ServicesDocument20 pagesPricing A ServicesErika MoralesNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Mix 7PsDocument4 pagesThe Marketing Mix 7PsNinaNo ratings yet

- Marketing 121Document5 pagesMarketing 121Mike JueraNo ratings yet

- SLM Un IT 5: Dr. Mithilesh PandeyDocument41 pagesSLM Un IT 5: Dr. Mithilesh PandeyVijay TushirNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledLouiss DejesusNo ratings yet

- Week 3 - Business Level Strategy - ResumeDocument4 pagesWeek 3 - Business Level Strategy - ResumeVinaNo ratings yet

- Target Costing: Kenneth Crow DRM AssociatesDocument6 pagesTarget Costing: Kenneth Crow DRM AssociatesAhmed RazaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management Price StrategyDocument30 pagesMarketing Management Price StrategyChali KumaraNo ratings yet

- Strategy - Chapter 6Document7 pagesStrategy - Chapter 632_one_two_threeNo ratings yet

- Catholic University of Eastern AfricaDocument15 pagesCatholic University of Eastern AfricaTerrenceNo ratings yet

- PricingDocument4 pagesPricingEmy MathewNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6. PricingDocument26 pagesChapter 6. PricingTadele BekeleNo ratings yet

- Pricing Strategies: Understanding Pricing Setting The Price Adapting The Price Initiating & Responding To Price ChangesDocument19 pagesPricing Strategies: Understanding Pricing Setting The Price Adapting The Price Initiating & Responding To Price ChangesHarshit Raj KarnaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter Six Pricing Decisions: Major Influences On Pricing DecisionDocument6 pagesChapter Six Pricing Decisions: Major Influences On Pricing DecisionTESFAY GEBRECHERKOSNo ratings yet

- CHP 12 - Strategy, Balanced Scorecard, and Strategic Profitability (With Answers)Document54 pagesCHP 12 - Strategy, Balanced Scorecard, and Strategic Profitability (With Answers)kenchong7150% (1)

- Five Generic StrategiesDocument39 pagesFive Generic StrategiesGaurav BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting 2 SummaryDocument47 pagesManagement Accounting 2 SummaryDanny FranklinNo ratings yet

- Ajmal - 1550 - 4118 - 1 - Pricing Strategy For Industrial Markets - Lecture # 14Document44 pagesAjmal - 1550 - 4118 - 1 - Pricing Strategy For Industrial Markets - Lecture # 14Raiana TabithaNo ratings yet

- 2-2.2. Pokayoke Check SheetDocument1 page2-2.2. Pokayoke Check SheetRavi YadavNo ratings yet

- APQP Workbook Master FileDocument107 pagesAPQP Workbook Master FileJOECOOL67100% (16)

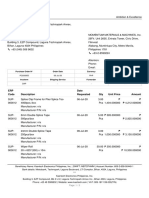

- Kaertech Electronics PO for Splice Clips and TapesDocument2 pagesKaertech Electronics PO for Splice Clips and TapesElena MosnitNo ratings yet

- Improve Customer Satisfaction SurveyDocument2 pagesImprove Customer Satisfaction Survey20UCC035 GOPINATH SNo ratings yet

- IC Quality Assurance Audit Checklist 11546 - WORDDocument2 pagesIC Quality Assurance Audit Checklist 11546 - WORDnafis2uNo ratings yet

- Assurance - Chapter 3 - STDocument67 pagesAssurance - Chapter 3 - STLinh KhanhNo ratings yet

- Risk Analysis For Engineers and EconomicsDocument3 pagesRisk Analysis For Engineers and Economicsjeronimo_mgNo ratings yet

- Annual ReportDocument304 pagesAnnual ReportPranav SahilNo ratings yet

- Annals Change FinalDocument92 pagesAnnals Change FinalandriNo ratings yet

- RevSOPexpinseu2015 KvnioownvniwonionvionwioviowoivnoiwDocument42 pagesRevSOPexpinseu2015 KvnioownvniwonionvionwioviowoivnoiwCult BoyNo ratings yet

- CIS Auditing Internal ControlDocument10 pagesCIS Auditing Internal ControlFrancineNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - Changes Related: (Clause Description-Paraphrase)Document11 pagesChapter 12 - Changes Related: (Clause Description-Paraphrase)mahesh KhatalNo ratings yet

- ACC2001 Lecture 9 Business Combinations IIIDocument46 pagesACC2001 Lecture 9 Business Combinations IIImichael krueseiNo ratings yet

- Zero Based Budgeting (ZBB)Document11 pagesZero Based Budgeting (ZBB)sagarNo ratings yet

- TTI Company Profile 2022Document9 pagesTTI Company Profile 2022michael thomasNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedures (Sop) ManualDocument12 pagesStandard Operating Procedures (Sop) ManualReagan MkiramweniNo ratings yet

- When Profitability and Quality Come Together: BeveragesDocument4 pagesWhen Profitability and Quality Come Together: BeveragesDũng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Final Assessment OutlineDocument2 pagesFinal Assessment OutlineMeshack MateNo ratings yet

- Certificate in Logistics Management OverviewDocument2 pagesCertificate in Logistics Management OverviewRifwan FadiansyahNo ratings yet

- Financial Control - 2 - Variances - Additional Exercises With SolutionDocument9 pagesFinancial Control - 2 - Variances - Additional Exercises With SolutionQuang Nhựt100% (1)

- The Four Phases of ChangeDocument7 pagesThe Four Phases of ChangeRaul EyzaguirreNo ratings yet

- Causes For Safety ObservationsDocument1 pageCauses For Safety ObservationsAlberto CastilloNo ratings yet

- Auditing and Assurance - HonoursDocument2 pagesAuditing and Assurance - HonoursVardaan JaiswalNo ratings yet

- FBM 3-9-21 Studs and TrackDocument4 pagesFBM 3-9-21 Studs and TrackRamonNo ratings yet

- Core Values of Total Quality Management 1. Customer-Driven QualityDocument6 pagesCore Values of Total Quality Management 1. Customer-Driven QualityLloydNo ratings yet

- Professional Scrum Master - Advanced: Refresh Your Knowledge With PSM I ContentDocument47 pagesProfessional Scrum Master - Advanced: Refresh Your Knowledge With PSM I ContentTharun Mani TejaNo ratings yet

- CAC1107200904 Accounting IADocument6 pagesCAC1107200904 Accounting IAGift MoyoNo ratings yet

- Solicited ProposalDocument12 pagesSolicited ProposalBernie D. TeguenosNo ratings yet

- PO Pembelan Air Minum Des20Document1 pagePO Pembelan Air Minum Des20faris nadhifNo ratings yet

- Inspection and Test PlantDocument121 pagesInspection and Test PlantMajid Dixon89% (9)