0% found this document useful (0 votes)

144 views28 pagesPython Loops and Subroutines Guide

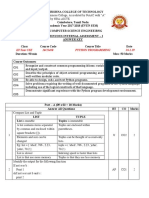

This document summarizes Python loops and functions. It discusses for and while loops, including examples of iterating over sequences and lists. It also covers nested loops. Functions are introduced as named blocks of reusable code that can take arguments and return values. The key difference between functions and procedures is that functions return a value. Examples are provided to demonstrate functions with arguments, return values, and variable scope.

Uploaded by

allenbaileyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

144 views28 pagesPython Loops and Subroutines Guide

This document summarizes Python loops and functions. It discusses for and while loops, including examples of iterating over sequences and lists. It also covers nested loops. Functions are introduced as named blocks of reusable code that can take arguments and return values. The key difference between functions and procedures is that functions return a value. Examples are provided to demonstrate functions with arguments, return values, and variable scope.

Uploaded by

allenbaileyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd