Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Community College and Social Mobility Janet Kirchner University of Nebraska

Uploaded by

api-183036000Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Community College and Social Mobility Janet Kirchner University of Nebraska

Uploaded by

api-183036000Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

The Community College and Social Mobility Janet Kirchner University of Nebraska

Note: This literature review was originally submitted for EDAD 831E on April 30, 2012

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

Introduction For many students who might not have the chance to go to college otherwise, the community college gives students a possibility for further education and a step toward better career opportunities. The community college, previously called the junior college and sometimes called the two-year college, currently has multiple missions: to prepare students for transfer, to prepare students for work through vocational programs, and to provide remedial and adult education (Rhoads & Valadez, 1996; Dougherty & Kienzl, 2006). Because of these multiple missions, some argue that the community college lacks a sense of identity (McGrath & Spear, 1991). For those seeking social mobility, the emphasis on vocational education in many community colleges may prevent students from moving up the social ladder (Clark, 1960; Brint & Karabel, 1989; Alba & Lavin, 1981; Dowd, 2003). Studies of transfer rates from community colleges to four-year institutions show low rates of transfer overall, but a particularly strong impact of socioeconomic status on transfer rates (Dougherty & Kienzl, 2006). Because so many students begin their college careers at the community college, it is important for students, parents, and the community to be aware of the higher education choices available to them and the social and economic impact each choice might have on a students future. This research review was guided by the following questions: 1. How does social class background impact student college choices and eventual success? 2. Does the community college aid in social mobility, or does it perpetuate the class system? 3. In what ways can the community college change to make social mobility more possible? In this review, I first provide a theoretical framework based on theories of social and cultural capital (social capital as the relationships that will help someone in life and cultural

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

capital as the knowledge relevant to a social setting that will help an individual fit into a certain cultural group) (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Coleman, 1988; Bourdieu, 1986). Second, I discuss social class studies of pre-college students (Lareau, 2003; Gorman, 1998; McNamara, Weininger, & Lareau, 2003) in order to present the challenges students from disadvantaged backgrounds face even before they reach college. Third, I discuss the community colleges role in social mobility, including the challenges the community college faces (Brint and Karabel, 1989; Dougherty and Kienzl, 2006); the strengths of the community college (Attewell & Lavin, 2007); and the potential for the community college to be a major force for social change (Rhoads & Valadez, 1996; Laden, 1999; Trujillo & Diaz, 1999). I then discuss implications for future research. Approach to reviewing the literature When conducting the search for literature, I used the following search terms: social class, socioeconomic status, race, community college, cooling out, multicultural, and working class. I conducted searches in FirstSearch, Eric, Google Scholar, and JSTOR. I did not limit the dates of the searches in order to be able to trace the historical development of the approaches toward the community college. I also incorporated readings from EDAD 831 as well as books focused on the community college. I chose to include literature from pre-college studies since these studies paint a picture of the students before they arrive at the community college, and what students bring with them has a profound impact on their success in college. Theoretical background America is often called the land of opportunity, and the prevailing narrative is that those who work hard can accomplish anything. However, this narrative ignores the inequalities

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

inherent in capitalism and education as it stands today. Bowles and Gintis (1976) argue that schools are constrained to justify and reproduce inequality rather than correct it (p. 102). Academic rewards are not based on capabilities, but on ones social economic status. Schooling legitimates and reinforces inequality by replicating the dominant structure in society in schools. For example, when students are tracked (placed into different courses based on IQ or other scores), students learn their place in their eventual occupations. In the lower tracks, students learn how to complete drills and become obedient, while in the higher tracks, students learn initiative and self-motivation. According to Bowles and Gintis (1976), students believe they are where they are meant to be based on their abilities. While society might believe that a persons chances are based on intelligence and motivation, Bowles and Gintiss (1976) work show that children often attain the same social status as their parents. Coleman (1988) introduces the idea of social capital, which includes the relationships, networks, and channels a person might have to help him or her in life. Social capital could be in the form of family members who are able to help guide a student through schooling, for example, or a community that works together to aid the members of the community. Another important form of capital is cultural capital, which is described by Bourdieu (1986) as knowledge, skills, and abilities relevant to certain settings. In education, both social capital and cultural capital are important in advancing ones status; without parental help or knowledge of the norms of the middle-class or upper-class, those with working-class backgrounds have little chance to succeed in elite educational or work situations.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

Pre-college inequality Lareaus (2003) qualitative study of poor/working-class and middle-class families shows a clear difference between middle-class and poor/working class childrens lives. Lareau (2003) studied 36 middle class, 25 working class, and 26 poor children from third grade classrooms. Through studying the families and their activities, she found that while middle-class parents work toward concerted cultivation, a plan to deliberately try to stimulate their childrens development and foster their cognitive and social skills (Lareau, 2003, p. 5), working-class and poor families work to provide the basic necessities of food and housing. The middle-class and upper-class families spend their days shuttling children to one activity after another, giving their children as many music, language, and sports lessons as possible. Much time is spent talking to the children as equals and giving children an opportunity to voice their opinions. By doing so, the parents are preparing them for elite colleges and work positions. By contrast, the workingclass and poor parents use more natural parenting, allowing the children to grow without as much interference. Working-class and poor parents see their position as keeping their children safe and fed. When it comes to schooling, middle-class parents are very involved in their childrens schooling, questioning teachers methods, paying attention to every move. Working-class and poor parents care about their childrens schooling, but they allow the teachers the authority when it comes to school. In their ethnographic study of parental networks, Horvat, Weininger, and Lareau (2003) found that middle-class families would talk about school issues with friends who were in education and research possibilities when it came to their children either having learning disabilities or being potentially gifted (p. 334). In Gormans (1998) qualitative study of parental attitudes toward education, he finds that while middle-class parents cannot imagine their children not going to college, working-class

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

parents often question the importance of college. In his interviews with working-class parents, Gorman finds hidden injuries of class, in which working-class people have had negative contact with those in the middle class and upper class and do not want their children to be a part of either class. These working-class parents value work and high school education, but do not think that college can necessarily bring about social mobility. Gorman (1998) notes that the interviews reveal three foci: middle-class language, middle-class clothing, and middle-class attitudes (p. 25). The working-class respondents had negative responses to each. One working class parent responds: I dont want to wear a shirt and tie to work, not have stress on me. I make $27 an hour. [I went] through an apprenticeship program and learn[ed] a trade they cant take away from [you] (Gorman, 1998, p. 27). Because so much value is placed on the work ethic and less on becoming a suit, its easy to see how working-class children often become workingclass adults. Persell and Cooksons (1985) qualitative study of the social networks between 42 private boarding schools and elite colleges shows how upper-class parents assure their childrens continued elite status by sending them to private boarding schools. These schools not only prepare their students for elite colleges and universities, but they also lead to social ties that will lead to business relationships and future marriages (Persell & Cookson, 1985, p. 114). Neither the working-class parent worried about the health of his or her child nor the middle-class parent worried about college preparation may realize the bartering process children of the elite benefit from as admissions counselors from elite boarding schools barter for admission to schools like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (Persell & Cookson, 1985).

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

The community college While the upper-class students go to elite private schools, and the middle-class students go to four-year institutions, the working-class and poor students often go to community colleges. According to David Kirp, Fewer than half of college-qualified graduates from families with incomes below $25,000 enroll in four-year colleges[]. By contrast, five out of every six students whose families earn more than $75,000 enroll in a four year institution (Weisberger, 2005, p. 127). Even though the community college supports the potential for social mobility through its open admissions policies and offering of developmental (remedial) coursework, the actual increase in social mobility is small. Clark (1960) argued that community colleges cooled out ambitions of its students by steering them toward vocational programs. Students might begin with the intention of eventual transfer, but through the number of remedial and general education courses required and low success with such courses, students would be advised into an Associates degree as their terminal degree. Thus, their ambitions toward higher education and a career that requires such education would be cooled out. This cooling out is problematic in the sense that those with an Associates degree have the potential for less social mobility than those with a Bachelors degree. Those who critique the institution of the community college (Clark, 1960; Brint & Karabel, 1989) assert that the community college acts as a buffer between the lower-class and the middle and upper class, assuring that lower-class students stay on a separate track. To test the cooling out theory (or the community college effect), Alba and Lavin (1981) studied the differences between students who began their educations at the community colleges with the City University of New York (CUNY) system compared to those who began at the community colleges, focusing on groups with similar academic and social backgrounds.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

Because the CUNY system was open admissions and because students with Associates degrees from CUNY system community colleges were guaranteed admission to CUNY, Alba and Lavin (1981) argued that making the comparison was a conservative test. Alba and Lavin (1981) found that there was a difference, that students placed in two-year schools did not stay as long in school, earned fewer credits and were less likely to earn the baccalaureate than academically similar students placed in the senior colleges (p. 235). They suggest that in other community colleges that did not have such clear transfer agreements, students would likely have an even more difficult time envisioning themselves at a four-year institution and may be more likely to finish with an Associates degree or drop out. Challenges Community colleges face multiple challenges, but a major challenge is their multiple missions (Rhoads & Valadez, 1996). Community colleges are meant to prepare students for transfer, offer vocational Associates degrees, offer continuing education programs for the community, offer remediation for those unprepared for college, and adult basic education for those preparing for GEDs (Dowd, 2003). Because community colleges are open door institutions, which anyone with a high school diploma or GED may attend, they must be ready to work with students from a variety of ages, backgrounds, and experiences. For those who view the community college as a transfer institution, they will be critical of the vocational culture of the community college (Herideen, 1998). Those who view the community college as a place to acquire job training resent the liberal arts courses the students must take (Rhoads & Valadez, 1996).

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

Economically, it is difficult for an institution to be all things to all people. Many community colleges must rely heavily on adjunct (part-time) faculty, who may not be able to be fully invested in any mission. Part-time professors are over half of the faculty on most community college campuses (McLaughlin, 2005). These part-time faculty members may have full-time jobs and teach one or two classes, or they might teach part-time in several institutions. McLaughlin (2005) recommends that part-time faculty have the same qualifications as full-time faculty, that they become part of the full-time departmental culture by participating in professional development activities, and that they participate in faculty meetings. In making these recommendations, however, it is clear that such involvement on campus is not the norm. The over-reliance on part-time faculty contributes to the feeling that the community college is a temporary place to be, for both faculty and students. For students at community colleges, economic issues are often central to their success or failure (Sullivan, 2005). In a content analysis at Manchester Community College of over 750 explanations of why students were placed on probation, most reasons were non-academic, such as illness, childcare, death, working too many hours, and difficulties with transportation (Sullivan, 2005). Sullivan (2005) writes, Unlike their peers at selective public and private colleges and universities, who pursue their studies in residence on campuses, usually without the distraction of full- or even part-time work, community college students are almost always less insulated from the unforgiving realities of life than their peers at selective institutions (pp. 150151). Likewise, Goldrick-Rabs (2006) longitudinal study of college pathways suggested that students who change schools often did so because of financial suffering rather than trying to find the best college fit. Goldrick-Rab (2006) writes: The findings of this study also suggest that

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

10

financial resources may matter more than access to information in shaping postsecondary pathways (p. 73). College is a challenge for any economically disadvantaged group, but it is particularly challenging for those on welfare. Levin, Montero-Hernandez, Cerven, and Shaker (2011) contend that federal and state policies make it difficult for welfare recipients to reach their goals at the community college. In an analysis of CalWORKS and the New Visions program at Riverside Community College, Levin, Montero-Hernandez, Cerven, and Shaker (2011) illustrate that many programs geared toward welfare recipients narrowly focus on job training. Because the students had a work requirement built into the program, the students either had difficulty keeping up with classes because of work or difficulty keeping up with work because of the classes. Levin, Montero-Hernandez, Cerven, and Shaker (2011) conclude that the outcomes of the programs were weak in part because of a difference in missions between the welfare agencies and the community colleges. Since those with a bachelors degree typically see a much higher increase in salary than those with an associates degree (for example, an associates might see a rise of 25 to 35 percent, while a bachelors could be a 75 percent increase), many researchers focus primarily on the community colleges transfer mission (Weisberger, 2005). Transfer data generally show that those who begin at a community college are less likely to graduate with a bachelors than those who begin at a four-year institution. The success rate of transfer to a highly competitive college from a community college is worse for poor students than affluent students. Dowd (2011) writes: Among high school graduates of the Class of 1992 who transferred to highly selective colleges and universities, 79 percent were from the two highest socioeconomic quintiles (p. 219). By contrast, those having the lowest level of socioeconomic status (SES) contributed a mere 2

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

11

percent of the student body who transferred to this group of colleges assigned the highest prestige rankings based on information in the Barrons Profile of American Colleges (Dowd, 2011, p. 219). In Dougherty and Kienzls (2006) study of community college transfer rates, they find that socioeconomic status and age have a negative impact on student transfer rates. Dougherty and Kienzl (2006) conducted a multivariate analysis using the National Education Longitudinal Study of the 8th Grade and the Beginning Post-secondary Students Longitudinal Study. Even though the time periods of transfer are only five and eight years, because the study looks beyond institutional transfer rates, the study gives a good overall picture of transfer rates. Goldrick-Rab (2006) takes the study of transfer further by looking not just at transfer but at how students often will take multiple paths to get to their degree. Students might start at a four-year institution, move to a community college, then return to another four-year institution, for example. Unfortunately, these nontraditional pathways that students take have a negative impact on degree completion (Goldrick-Rab, 2006). It is especially important for lower-SES students to have continuous enrollment. Goldrick-Rab (2006) writes: Students in the secondlowest SES quartile increased their chances for completion by 38 percent, and students in the lowest quartile increased their chances by 27 percent, by maintaining continuous enrollment (p. 65). Goldrick-Rabs (2006) longitudinal study of students based on the National Center of Education Statistics followed postsecondary pathways of 8,889 students. The study found that students from low-SES backgrounds were more likely to leave their four-year institutions to transfer to two-year colleges than advantaged students might. Advantaged students often moved instead from one four-year institution to another. Dowd (2003) illustrates the economic problem further by explaining that even at twoyear institutions, the cost of tuition has risen, but the financial aid available has not kept up with

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

12

student needs. Dowd (2003) writes, Among community college students in the lowest-income quartile in a study of federal student aid data, 92 percent were identified as needing federal aid, but only 63 percent of those with need receive aid, including grants and loans (p. 105). Because financial needs are not met by loans and aid, many low-income students work to supplement income, which often makes success in college difficult. Students who work less than fifteen hours a week do well in college, but those who work more are less likely to be successful (Dowd, 2003, p. 106). Although many see the issue of low-SES students dropping out or changing institutions as an economic one, it is just as important to understand the cultural challenges such students face when attending either the community college or a four-year institution. As Lareau (2003) found, middle-class families often make it their goal (whether consciously or unconsciously) to prepare children for college and middle-class and upper-class careers by scheduling their children in music, sports, and art classes that make them a part of a certain culture. Middle-class parents also encouraged their children to speak up to adults and to gain a sense of self (Lareau, 2003). Even though Lareau (2003) critiques the over-scheduling of the middle-class children and sees advantages to the more natural upbringing of the poor and working-class children, the poor and working-class children will lack the same cultural capital when attending college. While the middle-class children would have had exposure to much of the subject matter they will learn in their introductory college courses, the material in liberal arts courses may be quite new to poor and working-class children. The community college is thus faced with complex decisions. How do colleges transition poor and working-class students into a world with a different linguistic style and culture than their own?

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

13

Even though Willis (1981) case study of working class students is based on British students, the conversations between the students illustrate a culture opposed to authority, especially those in educational authority. Much of the lads focus is on having a laff. Even the parents are not disappointed by the boys trouble-making. Considering the boys do not have much more schooling left, both the boys and parents likely assume the next step is to get a job. For the children in Gormans (1998) study of working-class parents views toward education as well, the assumption is that these students will work after high school rather than go to school. More and more, though, students who had never intended to go to college now must go for economic reasons. Community colleges especially are faced with remediation of many students who are unprepared academically, socially, and culturally. As most universities and four-year institutions have eliminated remediation programs (often called developmental, basic, or foundational), it has become the community colleges job to offer courses to prepare students for college-level work (Dowd, 2003). Traditionally, many of these courses have been skills-based, reminding students of the worksheets they hated during their previous schooling. Developmental coursework then serves as another track within the community college, one some students struggle escaping. Rhoads and Valadez (1996) show that placement in developmental coursework is not necessarily only out of academic necessity but also because of lack of cultural capital many working-class and minority students may have. In their discussion of a case study of a college they name Remedial, Rhoads and Valadez (1996) write, What tends to occur is that the experience and knowledge of the middle- and upper-class students get legitimated and those of other students get situated on the margins (p. 139). An interview with a developmental student illustrates the challenges they face: I didnt take much math in high school, and I never took algebra. A teacher talked to me in

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

14

the ninth grade and asked if I was going to college, and at that time I didnt think I was, so he said I should take consumer math instead of algebra (p. 146). The student goes on to say that her mother hadnt thought about her going to college either and didnt know how to help. Community colleges then are faced with teaching many students who are unprepared on many levels for the challenges they face once they get there. Community colleges also are often more indebted to business ties than many four-year colleges and universities might be. Through business partnerships, the job of the community college is to train students for specific jobs. In Rhoads and Valadezs (1996) qualitative study of a vocational community college (which they name Vocational), they describe the curriculum as focused on the needs of specific skills employers have requested. In the classroom, knowledge is fragmented. Rhoads and Valadez (1996) state that it is clear from the classrooms that the faculty imagine that employers want quiet, compliant workers who will do as they are told. Because the vocational classes are so job specific, many students at Vocational have a difficult time with the general education courses. If the purpose of the learning is not perfectly clear, students often reject the course. In Dowds (2003) analysis of the community colleges ideology of efficiency, like Rhoads and Valadez (1996), she expresses concern for the growth of contract training programs in the community college. The difference between the contract training programs and the traditional vocational programs is that with the contract training, an outside entity is involved in college decisions, and these decisions can impact curriculum and instruction. Dowd (2003) critiques the college as business model since this culture minimizes the community colleges potential to focus on social issues. In studying California state policy documents, Dowd (2003) found, Although the concept of access, the cornerstone of the democratizing mission of the

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

15

community college, was articulated, it was harnessed to the goals of workforce development and divorced from the promise of upward mobility from which it derives its power (p. 98). The community colleges narrow focus on job skills may limit students transfer options in the long run. Strengths While the community college has been criticized for limiting social mobility on one hand, on the other, it is also the main chance for many students for further education beyond the high school diploma. For those needing remediation, the community college is increasingly the only place such student can go. Dowd (2003) writes that the American Association of Community Colleges reported that only 11 percent of colleges offered credits for remedial coursework. Most four-year colleges are eliminating developmental programs, including the City University of New York, which had been ground-breaking in its offering of developmental education (Goto, 2002). Florida, California, and New York are among the states that have moved toward relegating remediation to the community colleges. This change especially impacts students from low SES backgrounds since they are more likely to have had non middle-class educations, which are often necessary to do well on college entrance exams and entry exams. This also impacts non-traditional students, who may have been out of school for years and need brush-up before beginning college coursework. Without the community college, working adults who would like or need to have a career change would no longer have the opportunity. For students who struggled in school or for returning adult students, the community college may be the only option.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

16

While remediation has been critiqued as holding students back from graduation and transfer, Attewell and Lavin (2007) point out that without remediation, many other students would not graduate at all. They write, Looked at another way, nationwide 50 percent of African American BAs and 34 percent of Hispanic BAs graduate after taking remedial course work. If those students had been deemed unsuited for college and had been denied entry to four-year institutionsas some critics have recommendedthen a large proportion of the minority graduates in the high school class of 1992 would never have received degrees (Attewell and Lavin, 2007, p. 326). Further, students from every social class and academic background may need at least one remedial class. These classes offer students a second chance, but also a way to assure higher quality control for the institution (Attewell and Lavin, 2007). As the most economic option, the community college offers a chance for poor and working-class students to pursue further education. Even though scholarships may be available to four-year institutions, the culture of many four-year institutions does not support working students. Students from poor or working-class backgrounds may need to work to help support their families, and a community college close to home could be the only option. In addition, the community college offers training that four-year colleges do not offer. Some students truly enjoy working with their hands and want to be welders, automotive technicians, machine tool specialists, culinary artists, etc. Four-year institutions and universities do not offer these specializations. Gormans (1998) study illustrates the value many workingclass families place on labor and hard work over office work. The community college offers training for occupations that may give a higher rate of return than some occupations that require four-year degrees. For example, a student with an associates in machine tool technology is likely to earn more than a student with a bachelors in early childhood education. Attewell and

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

17

Lavin (2007) state that earnings for some associates degrees, such as business, natural sciences, math, computers, and health and social services were not significantly different from bachelors degree earnings in arts and humanities, social sciences, and education (p. 324). Those with an associates will average 1.4 times more than high school graduate (Dowd, 2003). For students who are tentative about higher education, the community college offers students a way to learn more about themselves and what career they might want to pursue. No matter the social class, many students do not know what they want to do for a living, and the community college offers a lower cost way to explore possibilities. For students from rural areas or small schools, the community college is often more comfortable since it offers smaller classes and is usually close to home. Some students from rural areas may not have considered going away to college, but will attend a community college in their own area. In this sense, the community college can serve as a transitional institution to one that will help students fulfill their educational goals. If the students discover they want a more hands on career, then the community college can help them fulfill these goals. Attewell and Lavin (2007) further argue that even those who do not finish with an associates degree earned more than those who did not attend. On average, the C or worse students who attended community college were earning between 13 percent and 15 percent more than their counterparts who only finished high school (Attewell and Lavin, 2007, p. 320). Attewell and Lavin (2007) also argue that the published graduation rates are sometimes misleading because of a short window of time given for students to graduate. When looked at over a longer period of time, rates for graduation improve. They say that two-thirds of college graduates receive their BAs within six years, and 19 percent take more than ten years to complete their degrees (Attewell and Lavin, 2007, p. 321). It is not that these students do not

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

18

receive their degrees; its just that they take a little longer than those with more privileged backgrounds. The community college and social change Community colleges have the opportunity to be more than a stopping point on the way to the bachelors degree or a place to become trained in a vocation. Community colleges can be at the forefront of social change by embracing the multiculturalism of their students. Rhoads and Valadez (1996) argue that teaching multiculturalism should go beyond just a class or two in diversity but be infused in the culture and structure of the institution. Rhoads and Valadez (1996) write, Our contention is that a commitment to democratic education, encompassed in the idea of a critical multicultural pedagogy, offers the cultural thread connecting the multiple functions of the community college (p. 48). In presenting case studies of community colleges with varying structures and cultures, Rhoads and Valadez (1996) show the struggles of some community colleges and the strengths of others. Community colleges with a narrow focus on vocational education, for example, could be brought to see that vocational education does not need to be as narrowly defined as skills for a job, but also could be broadened to include education for good citizenship. In their discussion of a community college focused on immigrants, they show a place that values Celebratory socialization--the idea that the culture, forms of knowledge, and ways of knowing that students bring with them to educational settings ought to be embraced within the organizational context (Rhoads and Valadez, 1996, p. 54). In Wassmer, Moore, and Shulocks (2004) regression analysis of transfer rates among 108 California community colleges, they found that community colleges with a higher percentage of either Latino or African American students have a lower transfer rate over a 6-year

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

19

period. Like Rhoads and Valadez (1996), they contend that colleges can do much more to respect student and community cultures. Wassmer, Moore, and Shulock (2004) write: In order to encourage and support underrepresented minority students in attaining the baccalaureate, state and institutional policies may need to be modified to respect and accommodate the cultures of these communities, focusing on the many students who are already transferring and persisting through graduation (p. 666). Institutions that have a transfer culture are more likely to have a higher transfer rate (Wassmer, Moore, and Shulock, 2004). Trujillo and Diaz (1999) provide a case study of the type of community college Rhoads and Valadez (1996) describe and Wassmer, Moore, and Shulock (2004) hope for. While many community colleges have low transfer rates, some have very high transfer rates, and Trujillo and Diaz (1999) analyze the ones that have the high transfer rates. Colleges that work to address student culture and promote a multicultural environment often have higher success rates. Palo Alto College in San Antonio is an example of a school that values the culture of the students while helping students find their place in the academic community (Trujillo & Diaz, 1999). Both the vocational and liberal arts programs are valued at Palo Alto College, but the vocational programs are not as big as the transfer program. Faculty and staff respect the students background and are part of the community surrounding the college. Critique and future research Much of the critique of the community college is based on quantitative methods, which have measured transfer rates. However, these methods often minimize or ignore the fact that many students do not enter the community college with the intent to transfer. These analyses also often ignore the gains students make from simply attending college. Without the community

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

20

college, many students career opportunities would be severely limited, more so than they might be with an Associates degree. Many of the qualitative case studies also depict a bleak picture of community college education, with classes that focus on remedial skills or occupational skills. Still, in the case studies of colleges that embrace multiculturalism, a picture of what the community college can be emerges. There is a lot of potential for future research. Many studies are conducted by university researchers without actual community college experience. Herideens (1998) ethnographic study of her own sociology classroom and a story-sharing group that spun off of this classroom is one of very few practitioner-based studies. Although qualitative case studies have been done that have focused on the community college classroom, more qualitative studies of community college students and their perceptions could fill in the gaps of this type of research. Much of the work done so far has focused on the transfer role of the community college, but more studies of vocational students themselves are important. What makes a student choose a vocational path? Studies that follow life paths of students who attend community colleges but then drop out would also add to the research. Much of the research also is focused on urban rather than rural areas. How does location affect community college outcomes? While many critiques of the community college are valid, the community college may be the only choice for students from poor and working-class backgrounds. As such, it is important to work toward improving the developmental, vocational, and liberal arts courses offered rather than eliminating or de-emphasizing any one element. A multicultural focus is one way to connect the multiple missions of the community college. A college culture that embraces a communitys culture rather than seeks to erase it is an important first step in leading toward more student success.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

21

References Alba, R. & Lavin, D. (1981). Community colleges and tracking in higher education. Sociology of Education, 54(4), 223-237. Attewell, P. & Lavin, D. (2007). Mass higher education and its critics. In A.R. Sadovnik, Sociology of education: A critical reader (2nd Edition). (pp. 313-340). New York: Routledge. Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In A.R. Sadovnik, Sociology of education: A critical reader (2nd Edition). (pp. 83-95). New York: Routledge. Bowles & Gintis (1976). Beyond the educational frontier: The great American dream machine. In Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. NY: Basic, 102-148 Brint, S. & Karabel, J. (1989). Community colleges and the American social order. In Arum, R., Beattie, I.R., & Ford, K. (Eds.). The structure of schooling: Readings in the sociology of education (2nd Edition). (pp. 510-520). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press/Sage Publications. Clark, B. (1960). The cooling out function in higher education. The American Journal of Sociology, 65(6): 569-576. Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95-121. Dougherty, K., & Kienzl, G. (2006). Its not enough to get through the open door: Inequalities by social background in transfer from community college to four-year colleges. In A.R.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

22

Sadovnik, Sociology of education: A critical reader (2nd Edition). (pp. 267-290). New York: Routledge. Dowd, A. (2003). From access to outcome equity: Revitalizing the democratic mission of the community college. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 586, 92-119. Dowd, A. (2011). Improving transfer access for low-income community college students. (2011). In A. Kezar (Ed.), Recognizing and Serving low-income students in higher education. (pp. 217-231). New York and London: Routledge. Goldrick-Rab, S. (2006). Following their every move: An investigation of social-class differences in college pathways. Sociology of Education, 79(1), 61-79. Gorman, T. (1998). Social class and parental attitudes toward education: Resistance and conformity to schooling in the family. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 27(10), 10-44. Goto, S. (2002). Basic writing and policy reform: Why we keep talking past each other. Journal of Basic Writing, 21(2), 4-20. Herideen, P.E. (1998). Policy, pedagogy, and social inequality: Community college student realities in post-industrial America. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. Horvat, E., Weininger, E., & Lareau, A. (2003). Social ties to social capital: Class differences in the relations between schools and parent networks, Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 319-351.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

23

Laden, B. (1999). Celebratory socialization of culturally diverse students through academic programs and support services. In Shaw, K., Valadez, J., & Rhoads, R. ). Community colleges as cultural texts (pp. 173-194). Albany: State University of New York Press. Lamont, M. & Lareau, A. (1988). Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps, and glissandos in recent theoretical developments. In Arum, R., Beattie, I.R., & Ford, K. (Eds.). The structure of schooling: Readings in the sociology of education (2nd Edition) (pp. 34-49)Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press/Sage Publications. Levin, J., Montero-Hernandez, V., Creven, C, and Shaker, G. (2011). In A. Kezar (Ed.) Recognizing and Serving low-income students in higher education (pp. 139-158) New York and London: Routledge. McGrath, D. & Spear, M. (1991). The academic crisis of the community college. Albany: State University of New York. McLaughlin, F. (2005). Adjunct faculty at the community college: Second-class professoriate? Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 33(2), 185-193. Persell, C., & Cookson, P. (1985). Chartering and bartering: Elite education and social reproduction. Social Problems, 33(2), 114-129. Rhoads, R.A. & Valadez, J.R. (1996). Democracy, multiculturalism, and the community college. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. Sullivan, P. (2005). Cultural narratives about success and the material conditions of class at the community college. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 33(2), 142-160.

THE COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

24

Trujillo, A. & Diaz, E. (1999). Be a name, not a number: The role of cultural and social capital in the transfer process. In Shaw, K., Valadez, J., & Rhoads, J. (Eds.) Community colleges as cultural texts (pp. 125-151). Albany: State University of New York Press. Wassmer, R., Moore, C., & Shulock, N. (2004). Effect of racial/ethnic composition on transfer rates in community colleges: Implications for policy and practice. Research in Higher Education, 651-672. Weisberger, R. (2005). Community colleges and class: A short history. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 33(2), 127-141. Willis, P. (1981). Elements of culture. In Arum, R., Beatttie, I.R., & Ford, K. (Eds.). The structure of schooling: Readings in the sociology of education (2nd Edition) (pp. 228242). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press/Sage Publications.

You might also like

- CHAPTER 1 Social Perspective in EducationDocument14 pagesCHAPTER 1 Social Perspective in EducationArceus GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Habitus Transformation and Hidden Injuries: Successful Working-Class University StudentsDocument15 pagesHabitus Transformation and Hidden Injuries: Successful Working-Class University StudentsArqueuosNo ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives On Education: Learning ObjectivesDocument17 pagesSociological Perspectives On Education: Learning ObjectivesRonnila BondeNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 PDFDocument21 pagesUnit 2 PDFAilix SumalinogNo ratings yet

- Communities, Schools, and Teachers: Mavis G. Sanders Claudia GalindoDocument24 pagesCommunities, Schools, and Teachers: Mavis G. Sanders Claudia GalindocharmaineNo ratings yet

- 11.2 Sociological Perspectives On Education: Learning ObjectivesDocument5 pages11.2 Sociological Perspectives On Education: Learning ObjectivesWJAHAT HASSANNo ratings yet

- Code-Switching To Navigate Social Class in Higher Education and Student AffairsDocument13 pagesCode-Switching To Navigate Social Class in Higher Education and Student AffairsHuyen Thu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives On EducationDocument9 pagesSociological Perspectives On Educationjeliza gransaNo ratings yet

- Sociological-Perspectives-in-Education LONG QUIZDocument29 pagesSociological-Perspectives-in-Education LONG QUIZJea Mae G. BatiancilaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Perspectives On Education: Tañedo, Angelica P. Bsed Filipino 1E - 4Document5 pagesTheoretical Perspectives On Education: Tañedo, Angelica P. Bsed Filipino 1E - 4Vea TañedoNo ratings yet

- Eam 2017 FinalDocument26 pagesEam 2017 FinalElma LiquitNo ratings yet

- Makinga DifferenceDocument15 pagesMakinga DifferenceJorge Prado CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Social Science Perspectives on EducationDocument7 pagesSocial Science Perspectives on EducationRamil Bagil LangkunoNo ratings yet

- Democracy N Diversity ClassDocument24 pagesDemocracy N Diversity ClassAndrew RihnNo ratings yet

- Educ 318 Research Paper FinalDocument14 pagesEduc 318 Research Paper Finalapi-284833419No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Profed 2Document9 pagesChapter 3 Profed 2Maximus YvosNo ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives on the Functions and Inequality of EducationDocument5 pagesSociological Perspectives on the Functions and Inequality of Educationmaria grace idaNo ratings yet

- Parental Influences That Impact First-Generation College StudentsDocument13 pagesParental Influences That Impact First-Generation College StudentsHaydden MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Lesson: Social Institution of Education (Week 2)Document5 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics Lesson: Social Institution of Education (Week 2)kimchuNo ratings yet

- EDU 5010 Written Assignment Unit 5Document5 pagesEDU 5010 Written Assignment Unit 5Thabani TshumaNo ratings yet

- Leg UpDocument21 pagesLeg Uparunkumar76No ratings yet

- May Citation NaDocument3 pagesMay Citation NareaganrevezaNo ratings yet

- Sociology HW 2Document5 pagesSociology HW 2Joyce Ama WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Sociological Theories of Education: FunctionalismDocument3 pagesSociological Theories of Education: FunctionalismChris EmekaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 3Document17 pagesPresentation 3Mousum KabirNo ratings yet

- Functionalist TheoryDocument6 pagesFunctionalist Theoryanon_877103538No ratings yet

- 文化资本与第一代大学生的成功Document21 pages文化资本与第一代大学生的成功dengruisi51No ratings yet

- Sociology AQA As Unit 2 Workbook AnswersDocument47 pagesSociology AQA As Unit 2 Workbook Answersolatunbosuno161No ratings yet

- Mills Gale 2007 IJQSE Finalauthoversion PDFDocument13 pagesMills Gale 2007 IJQSE Finalauthoversion PDFMasliana SahadNo ratings yet

- Lynch InequalityHigherEducation 1998Document35 pagesLynch InequalityHigherEducation 1998Minaal AhmedNo ratings yet

- Socialogical Theories in EducationDocument4 pagesSocialogical Theories in EducationKaumba kilayiNo ratings yet

- Dumais 2002Document26 pagesDumais 2002Lobsang ParraNo ratings yet

- Education's Role in Society and Economic DevelopmentDocument6 pagesEducation's Role in Society and Economic DevelopmentShelton MwayedzaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Democratic CitizenshipDocument7 pagesTeaching Democratic CitizenshipFreddy JunsayNo ratings yet

- Education Revision Notes 2010: SCLY 2 Education and Methods in ContextDocument35 pagesEducation Revision Notes 2010: SCLY 2 Education and Methods in ContextJul 480weshNo ratings yet

- Mojerrq-1 35 1 9-1Document7 pagesMojerrq-1 35 1 9-1api-253305344No ratings yet

- Diversity ReflectionDocument6 pagesDiversity Reflectionapi-321351703No ratings yet

- Social Capital 3Document14 pagesSocial Capital 3Adz Jamros Binti JamaliNo ratings yet

- Functions of EducationDocument5 pagesFunctions of EducationMarvie Cayaba GumaruNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On Dewey's Democracy and (Special) EducationDocument15 pagesThoughts On Dewey's Democracy and (Special) EducationLaura Elizia HaubertNo ratings yet

- Sociology Perspective On EducationDocument9 pagesSociology Perspective On EducationHisyam AhmadNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Re-Inventing America'S Public Schools 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: Re-Inventing America'S Public Schools 1MathewNo ratings yet

- Langhout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDocument22 pagesLanghout and Mitchell - Hidden CurriculuDiana VillaNo ratings yet

- Reexamining Social Class Differences in The Availability and The Educational Utility of Parental Social CapitalDocument36 pagesReexamining Social Class Differences in The Availability and The Educational Utility of Parental Social CapitalAlina Minodora TothNo ratings yet

- CARRINGTONDocument11 pagesCARRINGTONEffie LattaNo ratings yet

- Esa - Shira FeiferDocument11 pagesEsa - Shira Feiferapi-395661647No ratings yet

- Social Justice and Educational Delights: Morwenna Griffiths University of EdinburghDocument12 pagesSocial Justice and Educational Delights: Morwenna Griffiths University of EdinburghAmandeep Singh RishiNo ratings yet

- Molly Siuty Teaching StatementDocument2 pagesMolly Siuty Teaching Statementapi-315522556No ratings yet

- Socio-Educational TheoristsDocument30 pagesSocio-Educational TheoristsMarvie Cayaba GumaruNo ratings yet

- Edum 001 ReportDocument4 pagesEdum 001 ReportBenz DyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum debate important for social justiceDocument20 pagesCurriculum debate important for social justiceJ Khedrup R TaskerNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Lesson-2Document5 pagesChapter1 Lesson-2Domi NyxNo ratings yet

- International Perspectives on Equity and Inclusion (EDUC70322Document19 pagesInternational Perspectives on Equity and Inclusion (EDUC70322mauricio gómezNo ratings yet

- Cultural Capital and School Success: The Impact of Status Culture Participation On The Grades of U.S. High School StudentsDocument14 pagesCultural Capital and School Success: The Impact of Status Culture Participation On The Grades of U.S. High School StudentsGabi GeorgescuNo ratings yet

- Change PortfolioDocument4 pagesChange Portfolioapi-644894206No ratings yet

- Villegas - Dispositions in Teacher Education - A Look at Social JusticeDocument12 pagesVillegas - Dispositions in Teacher Education - A Look at Social JusticeaswardiNo ratings yet

- Primera - Generacion - Capital Cultural - Yoso - ComunidadDocument20 pagesPrimera - Generacion - Capital Cultural - Yoso - Comunidadcristian rNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 5 Social OrganizationsDocument9 pagesLECTURE 5 Social Organizationssamson egoNo ratings yet

- 1718Document11 pages1718Augues NZOULOU MABIALANo ratings yet

- ReferencesDocument14 pagesReferencesapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Trauma and The Developmental Writing Classroom Janet Kirchner University of NebraskaDocument24 pagesTrauma and The Developmental Writing Classroom Janet Kirchner University of Nebraskaapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Appendixc Swidlerobservation2Document14 pagesAppendixc Swidlerobservation2api-183036000No ratings yet

- Professional Development and The Developmental Writing ClassroomDocument13 pagesProfessional Development and The Developmental Writing Classroomapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Artifacts Strand C ChangedDocument3 pagesArtifacts Strand C Changedapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Appendxbinterview 930Document7 pagesAppendxbinterview 930api-183036000No ratings yet

- Narrative Inquiry and The Developmental Writing ClassroomDocument17 pagesNarrative Inquiry and The Developmental Writing Classroomapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Running Head: The First-Level Developmental Writing Classroom 1Document22 pagesRunning Head: The First-Level Developmental Writing Classroom 1api-183036000No ratings yet

- Appendixaobservation 1Document16 pagesAppendixaobservation 1api-183036000No ratings yet

- Stranda Narrative PortfolioDocument25 pagesStranda Narrative Portfolioapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Developmental Writing and The LiteratureDocument13 pagesDevelopmental Writing and The Literatureapi-183036000No ratings yet

- An Invitation: My Pedagogical Creed Janet Kirchner University of NebraskaDocument13 pagesAn Invitation: My Pedagogical Creed Janet Kirchner University of Nebraskaapi-183036000No ratings yet

- Nel Edu Guide Numeracy PDFDocument64 pagesNel Edu Guide Numeracy PDFHendra WcsNo ratings yet

- Rachel Wilburn ResumeDocument1 pageRachel Wilburn Resumeapi-534691266No ratings yet

- TOK Exhibition - Everything You Need To KnowDocument24 pagesTOK Exhibition - Everything You Need To KnowAlon AmitNo ratings yet

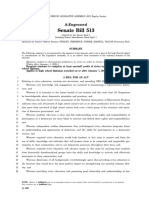

- Senate Bill 513: A-EngrossedDocument6 pagesSenate Bill 513: A-EngrossedSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNo ratings yet

- Clil Lesson Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesClil Lesson Plan Templatesandovalz24433% (3)

- API 510 Certification Prep: 60-hr Pressure Vessel Inspector CourseDocument1 pageAPI 510 Certification Prep: 60-hr Pressure Vessel Inspector CourseAbu Huraira50% (2)

- EOY Exams 2023 Grade 8Document1 pageEOY Exams 2023 Grade 842ync72cnjNo ratings yet

- Year 6 Newsletter Summer 2014Document3 pagesYear 6 Newsletter Summer 2014DownsellwebNo ratings yet

- Principles of Good Test AdministrationDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Good Test Administrationasghar KhanNo ratings yet

- SE Application FormDocument3 pagesSE Application FormPilar DurandNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Students' Performance in Modular LearningDocument4 pagesFactors Affecting Students' Performance in Modular LearningRomar SantosNo ratings yet

- 3E Presentation Profile Building Summer 2023 JSS School ShortDocument15 pages3E Presentation Profile Building Summer 2023 JSS School ShortKavya AroraNo ratings yet

- Memo HoneyDocument14 pagesMemo HoneyHoneyly UnayanNo ratings yet

- New CVDocument2 pagesNew CVMaung RkNo ratings yet

- Silabus PKBTP Gasal1920Document11 pagesSilabus PKBTP Gasal1920rizkiNo ratings yet

- Student AdminDocument1,961 pagesStudent AdminNaveenNo ratings yet

- Middle School Syllabus - Hawaiian StudiesDocument2 pagesMiddle School Syllabus - Hawaiian StudiesmespenceNo ratings yet

- Learning Delivery Modalities Course 2 Meeting MinutesDocument2 pagesLearning Delivery Modalities Course 2 Meeting MinutesJaps De la Cruz100% (4)

- Anne Swan, Pamela Aboshiha, Adrian Holliday Eds. EnCountering Native-Speakerism Global Perspectives PDFDocument222 pagesAnne Swan, Pamela Aboshiha, Adrian Holliday Eds. EnCountering Native-Speakerism Global Perspectives PDFAlin Paul CiobanuNo ratings yet

- 4873 9522 1 SMDocument10 pages4873 9522 1 SMFazrul PNo ratings yet

- Definition of Eductaion Unit 1.1 F.edDocument16 pagesDefinition of Eductaion Unit 1.1 F.edArshad Baig MughalNo ratings yet

- Prem ResumeDocument3 pagesPrem ResumepremsinghmeenaNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mathematics 1 - Q3 - W6Document6 pagesDLL - Mathematics 1 - Q3 - W6Kezia NadelaNo ratings yet

- NLE 11-2014 Room Assignment BaguioDocument111 pagesNLE 11-2014 Room Assignment BaguioPRC Baguio100% (1)

- Q On FoundationsDocument32 pagesQ On FoundationsCarol Justine EstudilloNo ratings yet

- (Julie Allan) Rethinking Inclusive Education TheDocument182 pages(Julie Allan) Rethinking Inclusive Education TheMonaLupescuNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument20 pagesCurriculum DesignRose Glaire Alaine TabraNo ratings yet

- Food Allergy ProjectDocument2 pagesFood Allergy Projectapi-242793948No ratings yet

- Creating and Managing Organizational CultureDocument26 pagesCreating and Managing Organizational CultureMas JackNo ratings yet