Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Asthma and Children Living in Poverty

Uploaded by

api-241782132Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Asthma and Children Living in Poverty

Uploaded by

api-241782132Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: Asthma in Children in Poverty

Asthma and Children Living in Poverty A Wellness Promotion Project NUR. 474 SUNY IT July 16, 2013

Asthma in Children in Poverty Asthma is described as a chronic airway disorder which is characterized by periods of reversible airflow obstruction referred to as asthma attacks. The airflow is obstructed by inflammation and hypersensitivity caused by a reaction to exposures called Triggers. Triggers

can be identified as chemicals, smoke, exercise and infections to name a few. Symptoms include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. There is no cure for asthma but there are methods of control to prevent exacerbations. Asthma is an area for primary prevention and wellness promotion in children. Education regarding the disease, and maintaining healthy living environments help prevent unnecessary hospital visits and hospitalizations. It also helps reduce the loss of days from school and provides a higher quality of life in children with asthma. A primary focus for review is children with asthma that are living in poverty. There are many areas of this topic that can be reviewed and are a strong concern for promotion of the health and wellbeing of children living in the United States (CDC, 2013a). The statistics for Asthma show an increase in incidence from 7.3% in 2001 to 8.4% in 2010. In the United States there are 25.7 million people living with Asthma; 7 Million of those are children. Asthma prevalence is highest in children, females and those whose family income is 100% less than the poverty level. The highest incidence of asthma is found in multiracial groups at 14.1%. The Asian population has the lowest incidence at 5.2%.Mortality is 15% per 1000 persons. Rates are 30% higher in females than males (CDC, 2012). Education is important to the multi-racial individuals as well as the African American population because of their high rate of incidence of asthma. When combined with poverty the statistics are much lower for outcomes of success. There are 2 million emergency rooms visits yearly for asthma. The African American population has a 330% higher rate than Caucasians for emergency room visits in addition to a 220% higher hospitalization rate, and a 180% higher death rate (CDC, 2013b).

Asthma in Children in Poverty

When analyzing the population that resides in the inner city of Albany the majority of the children that utilized the clinic in need of care were of African American or multi-racial descent, who lived in poverty and a large number were obese. Obese children have the highest lifetime and current asthma prevalence (CDC, 2013b). The community diagnosis for this population is Knowledge deficit related to learning barriers as evidenced by higher incidence of asthma in the community. In coordination with the Healthy People 2020 objectives the goal for respiratory diseases is to promote respiratory health through better prevention, detection, treatment, and education efforts. Objectives for this goal under the Healthy People Initiative are to reduce asthma death in children, reduce hospitalizations, ER visits, missed days of work and school, and increase the proportion of persons with current asthma who receive appropriate asthma care according to National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines (Healthy People.gov, 2013) The goals for the education to the community are to increase awareness of the triggers and effective treatment and maintenance strategies. In attaining these goals I utilized a variety of domains of learning. Utilizing the cognitive domain I asked patients and their families to recall information that had been presented to them regarding the asthma medication to determine the efficacy of teaching. Evaluating the Affective domain was completed by evaluating the patient and their families willingness to learn. Psychomotor ability was completed in watching the patient utilize the nebulizer, spacer etc. The project was conducted in conjunction with a Certified Asthma educator. The education and presentation was provided to patients during an asthma education class that newly diagnosed patients were asked to attend. Additional education was planned on being completed to area ministers in an effort to utilize the trusted members of the community. The planned education for ministers is to include basic information about asthma

Asthma in Children in Poverty

and medication management and a guide to resources to provide to parishioners who need further information. The information provided by the ministers is not to replace medical advice but to provide supplemental support and encouragement to utilize available medical resources in the community to effectively manage and treat the asthma. Local medical providers and area hospitals have come together to provide information and support to the community by being an active part of local community events and celebrations. One of the events that the partnership has provided information at is the Take Back the Streets which is held every Saturday 12-4. The challenges associated with this population were extensive in learning ability and readiness to learn. A large percentage of the population has multiple barriers to learning. Some of the barriers included lack of education, illiteracy, emotional and physical distress and no desire to learn. The patients and families lack of desire to learn was the most challenging barrier to overcome. Education was provided to asthma patients on every visit. Non-compliance was a contributing factor in the poor management and control of the asthma. In a review of the literature regarding children with asthma living in poverty there was a significant amount of research completed regarding this topic. One study found there to be a higher rate of hospitalizations for asthmatics that were living in poverty conditions, and were an ethnic minority. Explanations for this increase were that this population relied on crisis management for their disease controls; as well as the majority of the patients were under medicated at the time of the hospital visit. Other contributing factors that were identified were the patients were under-utilizing primary care facilities, lacked an asthma control plan, resided in adverse living conditions, and were exposed to a variety of psychosocial problems. (Rona, 2000) Medicaid has improved the quality of healthcare provided to children living in poverty. Although challenges still occur within the healthcare system. In identifying ways to reduce the growing

Asthma in Children in Poverty number of hospital visits a study looked at patients who presented to an ER related to asthma care, and provided them with a series of questions. In identifying the cause of visit it was

identified that the wait for an appointment was too long, unavailability of care when it was felt to be needed, inconvenient office hours with limited to no evening or telephone hours, and challenges related to transportation and care for other children. 24.1% of hospital patients surveyed indicated no telephone support in regards to asthma care (Crain, Kercsmar, Weiss, Mitchell & Lynn, 1998). Socio-economic status is strongly related to asthma morbidity. Factors associated with this include children whose family experienced 2 or more hardships were at an increased risk of reutilizations of ER services within a 12 month period than those without hardships. Children of caregivers at risk for psychosocial hardships were also at an increase risk for reutilization of ER services (Beck, Simmons, Huang & Kahn, 2012) Much of the research that has been completed regarding asthma care and children in poverty is based on their lifestyle and living conditions. In a study that was completed with 1528 children with asthma ages 4-9 reviewed possible contributing factors to the patients uncontrolled asthma. The assessment was completed by the childs caregiver. The children were recruited from Emergency Rooms and inner city clinics. The average age of the children who partook in the study was 6.2 and 62% were boys. 79.9% were in school and 73% were African American. Of the caregivers 53.8% were single and 61% indicated income below the poverty level. Possible contributing factors to the childs condition includes admission to the NICU at birth 24.7%, ventilator at birth 10.3%, 17.9% had a low birth weight <5.5 lbs at birth, and 57.4% had a family history of asthma. Other areas that were reviewed included the patients access to care which 38.4% utilized a hospital based pediatric clinic and 36.1% utilized a health clinic and 67.4% of children saw the same provider for both their asthma follow-up and primary care.

Asthma in Children in Poverty When the medications that the children were utilizing were analyzed 17% were not using any asthma medication. The most concerning piece of data that was retrieved was that 29% of the caregivers reported the school did not allow administration of asthma medication. Triggers to

asthma attacks can be found in many areas of the environment. Data regarding the homes that the children resided in were reviewed and the majority 57% lived in apartments with 44% of those being older than 5 years. 41% had wall-to-wall carpeting and only 38% of those had a functional vacuum cleaner. Visible signs of roach infestation were seen in 66% and rodents 29%. Smoking is a major concern for children with asthma. 59% of the families reported one smoker in the household and, more than 10% were smoking at the time of the home visit. Urine samples were collected from the children and they showed that 48% of them were exposed to second hand smoke within the past 24 hours. ( Kattan, Mitchell, Eggleston et al., 1997) The adherence to medication regimes is another area of focus that one study reviewed. A sample of low income patients that utilized a Metered Dose inhaler (MDI) was reviewed. The canister was weighed and determined that it was only being used 44% of the prescribed time. The patients technique of utilizing the inhaler was also reviewed and 25% had improper usage. An electronic device was imbedded in a prescribed MDI and results showed that 60% of the time there were either no doses administered or use was minimal. These findings also reflected a high percentage of patients that missed regular asthma follow-up appointments. When looking at ways to improve medication compliance thoughts are directed to empowering the children. In a review of nine years old patients 50% had primary responsibility for their asthma treatment.(Rona, 2000) One of the main concerns of children with asthma was their attendance at school and their ability to achieve academic standards with frequent absences. There are currently no federal

Asthma in Children in Poverty standards that regulate the environmental safety of school. Environmental hazards that can trigger asthma attacks such as mold, poor air quality and contaminated playgrounds are all a concern. Within the school there are many areas of concern for asthma such as the building materials, heating and cooling systems, and surrounding neighbors air quality. The potential

exposures that exist in the school are of a great concern as children consume more water, air and food than adults per unit of body. Children also have higher risks of exposure because of frequent hand to mouth and playtime behaviors. The outdoor air quality and land use affects indoor air quality through the normal air exchange process. Air quality is a big concern in gym areas at school because of the increased respiration rate of the children during exercise increases the intake of particulates in the air. The challenges associated with the school conditions are mainly focused on the inequalities in finances. Poorer school districts cannot afford the same amenities that wealthier school districts can which creates a greater challenge for the children in inner city schools. (Sampson, 2012) In all of the literature the common factor remains that the frequency of asthma symptoms, a previous hospitalization, and severe asthma were a result of reoccurring ER visits. Other areas of concern were 52.5% of the children with severe asthma had no preventative medications, 50% of the physicians did not discuss symptom management, and only 21.2 of the children with moderate to severe asthma were prescribed a peak flow meter (Crain, Kercsmar, Weiss, Mitchell & Lynn, 1998) The health and wellbeing of a child is characterized and influenced by many factors such as genetics, race, age, socio-economic factors and environmental characteristics (Adejuyigne, 2012). Based on the above presented information there are many areas of education and improvement that can be had within the healthcare environment to improve the quality of life for

Asthma in Children in Poverty children living with asthma in poverty conditions. In evaluating the effectiveness of the project there were challenges in obtaining data. A large percentage of patients missed appointments and only showed up for episodic visits. Attached is the Asthma Action Plan which is a

communication to both the patients and their family of what medication to take and when to take it. They are instructed to place this on their refrigerator and refer to it as needed to help provide effective relief of their symptoms. The overall statements made from patients caregivers were a lack of understanding of utilizing the preventative medications even when they are not having any symptoms. The Asthma Action plan is attached to the front of the patients chart and is reviewed on every visit. The children are involved in discussions about the frequency of use of their medications and how they evaluate their overall health. The goals I set were to provide basic education and information to patients and their families. The caregivers were somewhat receptive but I dont feel enough to retain the presented information. I feel that if I were to recreate the program I would create a 3 session education series and implement an incentive program for attending. Additional incentives awarded for healthy behaviors etc. Overall I enjoyed completing this project and have a better understanding of asthma and the struggles in maintaining a healthy child.

Asthma in Children in Poverty

References Adejuyigbe, E. (2012). The influence of neighborhood characteristics on the existance of asthma in children.

Beck, A. F., Simmons, J. M., Huang, B., & Kahn, R. S. (2012). Geomedicine: Area-Based Socioeconomic Measures for Assessing Risk of Hospital Reutilization Among Children Admitted for Asthma. American Journal Of Public Health, 102(12), 2308-2314. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300806

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2013a). Basic information. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/faqs.htm

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects. (2013b). Asthmas impact on the nation. Retrieved from website: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/impacts_nation/AsthmaFactSheet.pdf

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2012). Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 20012010. 94, Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db94.htm

Crain, E., Kercsmar, C., Weiss, K., Mitchell, H., & Lynn, H. (1998). Reported difficulties in access to quality care for children with asthma in the inner city . journal of American Medicine, 152(4), 333-339. Retrieved from http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=189411

Healthy People.gov. U.S Department of Health and Human Services, (2013). Respiratory diseases. Retrieved from website: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=36

Asthma in Children in Poverty

10

Kattan, M., Mitchell, H., Eggleston, P., Gergen, P., Crain, E., Redline, S., Weiss, K., & Kaslow, R. (1997). Characteristics of inner-city children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology, 24, 253-262. Retrieved from http://centerforhealthyhousing.org/Portals/0/Contents/Article0358.pdf Rona, R. (2000). Asthma and poverty. Thorax An International Journal of Respiratory Medicine, 55, 239-244. Retrieved from http://thorax.bmj.com/content/55/3/239.full.pdf Sampson, N. (2012). Environmental Justice at School: Understanding Research, Policy, and Practice to Improve Our Children's Health. Journal Of School Health, 82(5), 246-252. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00694.x

You might also like

- Sociology Family PaperDocument7 pagesSociology Family Paperapi-241782132No ratings yet

- RecDocument2 pagesRecapi-241782132No ratings yet

- Scholarly ProjectDocument11 pagesScholarly Projectapi-241782132No ratings yet

- SchizophreniaDocument13 pagesSchizophreniaapi-241782132No ratings yet

- 5 Year AwardDocument1 page5 Year Awardapi-241782132No ratings yet

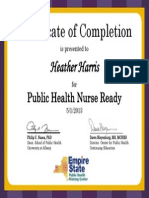

- Certificate HarrisDocument1 pageCertificate Harrisapi-241782132No ratings yet

- EvaluationDocument7 pagesEvaluationapi-241782132No ratings yet

- Healthcare Provider: HeartDocument1 pageHealthcare Provider: Heartapi-241782132No ratings yet

- Rotating Asset AccountingDocument4 pagesRotating Asset Accountingapi-241782132100% (1)

- Nys LicenseDocument1 pageNys Licenseapi-241782132No ratings yet

- Harris ResumeDocument4 pagesHarris Resumeapi-241782132No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PHD Thesis PDFDocument169 pagesPHD Thesis PDFStefania IordacheNo ratings yet

- Post-Disaster Housing ReconstructionDocument16 pagesPost-Disaster Housing ReconstructionSonia GethseyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bahasa InggrisDocument10 pagesJurnal Bahasa Inggrisnisaulhafizah8No ratings yet

- Student Health and Performance: The Impact of School Buildings OnDocument36 pagesStudent Health and Performance: The Impact of School Buildings OnAlisher SadykovNo ratings yet

- TES-AMM Analysis Pyrometallurgy Vs Hydrometallurgy April 2008Document6 pagesTES-AMM Analysis Pyrometallurgy Vs Hydrometallurgy April 2008papiloma753100% (1)

- CBE Lawsuit Vs Tesoro and AQMDDocument38 pagesCBE Lawsuit Vs Tesoro and AQMDSam GnerreNo ratings yet

- Air Pollution Lect.1Document277 pagesAir Pollution Lect.1Nah Sr AdNo ratings yet

- Abstract PollutionDocument4 pagesAbstract Pollutionlogeshboy007No ratings yet

- WLPGA Annual Report 2016 PDFDocument44 pagesWLPGA Annual Report 2016 PDFSanjai bhadouriaNo ratings yet

- Climate Crisis Action PlanDocument547 pagesClimate Crisis Action PlanThe National DeskNo ratings yet

- Bhimashankar SSK DetailsDocument7 pagesBhimashankar SSK Detailssumit gulatiNo ratings yet

- Air Pollution: Cause and Effect EssayDocument1 pageAir Pollution: Cause and Effect EssayQUỲNH ĐOÀN THỊ PHINo ratings yet

- Industrial Ventilation CapDocument19 pagesIndustrial Ventilation CapDaniel FerreiraNo ratings yet

- BKC4543 - Environmental Engineering 21516 PDFDocument16 pagesBKC4543 - Environmental Engineering 21516 PDFmiza adlinNo ratings yet

- Kaplan Power Profile 2021Document28 pagesKaplan Power Profile 2021Tewodros GetachewNo ratings yet

- Letter To Editor The Existence of Factories That Interfere With Human SettlementsDocument2 pagesLetter To Editor The Existence of Factories That Interfere With Human SettlementsaureliaapriliantyNo ratings yet

- What Are Eco Friendly ProductsDocument4 pagesWhat Are Eco Friendly Productsmukul1234No ratings yet

- FY00 Welding Emissions-Mgmt-AppilicableDocument39 pagesFY00 Welding Emissions-Mgmt-AppilicablePeter's KitchenNo ratings yet

- TNPCB and PublicDocument187 pagesTNPCB and Publicsaravana_ravichandra100% (1)

- (8806) English Grade 10 FAS April SET1Document2 pages(8806) English Grade 10 FAS April SET1Preethi Bharath RajNo ratings yet

- Humble Group Investor Presentation 26 March 2021Document30 pagesHumble Group Investor Presentation 26 March 2021atvoya JapanNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis - Ebike For Commuter Traffic PDFDocument58 pagesMaster Thesis - Ebike For Commuter Traffic PDFminaNo ratings yet

- Industrial Pollution by AnasDocument22 pagesIndustrial Pollution by AnasMuhubo MusseNo ratings yet

- Carbon Footprint Calculation GuideDocument22 pagesCarbon Footprint Calculation GuideRafael COVARRUBIAS100% (2)

- Air Quality Standard BIDocument1 pageAir Quality Standard BIFirrdhaus SahabuddinNo ratings yet

- UM3 Indicator 4.1 v1.1 37ppDocument37 pagesUM3 Indicator 4.1 v1.1 37ppvladNo ratings yet

- Analytical Chemistry 3 (CHEM 448) Quality and Air Pollution MCQDocument8 pagesAnalytical Chemistry 3 (CHEM 448) Quality and Air Pollution MCQYoussef AliNo ratings yet

- An Atlas of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, COPD (Hansel, Trevor T. Barnes, Peter J)Document387 pagesAn Atlas of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, COPD (Hansel, Trevor T. Barnes, Peter J)RLibdehNo ratings yet

- Underground Coal MiningDocument9 pagesUnderground Coal MiningSiddharth MohananNo ratings yet

- Group: 3 Members: 1. Regine E. Julian 2. Riselyn Jane Jabla 3. Rhona Jane Lontayao 4. Marie Conney Lagunay 5. Silvestre DionelaDocument2 pagesGroup: 3 Members: 1. Regine E. Julian 2. Riselyn Jane Jabla 3. Rhona Jane Lontayao 4. Marie Conney Lagunay 5. Silvestre DionelaRegine Estrada JulianNo ratings yet